Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peter Owen Publishers

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

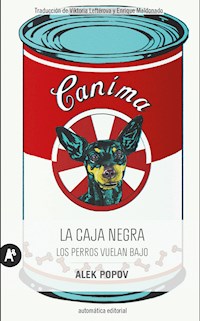

The Black Box is the latest satirical novel from one of Europe's funniest and most exciting emerging writers. In 1990 two Bulgarian brothers, Ned and Angel, receive an unusual package from the USA: a black plastic box containing the ashes of their late father. But can either of them be sure he is he really dead? Fifteen years later, as the brothers forge new and very different lives in their new home in New York, some answers begin to emerge . . . A darkly comic tale of disillusionment, The Black Box explores the nature and logic of our Western neo-liberal capitalist system and how so many of us are all driven to acts of greed, imprudence and recklessness in the pursuit of money and wealth. Peter Owen Publishers has over many decades published authors of international renown. Our list contains 10 winners of the Nobel Prize in Literature, and we continue to promote in English the best writers from around the world. Visit us at www.peterowen.com and follow us @PeterOwenPubs

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 427

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

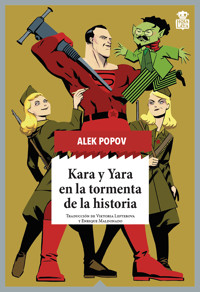

Alek Popov (born in Sofia, Bulgaria, 1966) is one of the most popular contemporary Bulgarian writers, working not only as a novelist but as a dramatist, essayist and short-story writer. His hugely successful first novel, the comic satire Mission London, based on his experiences as Bulgarian cultural attaché in London, has been translated in sixteen languages, including English. The book was filmed in 2010, becoming the most popular Bulgarian film since the revolution of 1990 and being described by Variety as ‘a breakthrough phenomenon’.

He has won many literary awards, including the Elias Canetti Prize (for The Black Box), the Helkon Award, the Chudomir Award, the Reading Man Prize and the Ivan Radoev National Prize for Drama. In 2012 he was elected corresponding member of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences in the field of the arts, the youngest member of the academy to date. He serves on the board of Bulgarian PEN and is part of the editorial body of the literary magazine Granta Bulgaria.

Award-winning The Black Box, his second novel, has so far appeared in six languages, including this English-language edition, and was a bestseller in German translation as well as the original Bulgarian.

Also by Alek Popov

MISSION LONDON

Contents

Prologue

1: Angel

2: Ned

3: Angel

4: Ned

5: Angel

6: Ned

7: Angel

8: Ned

9: Angel

10: Ned

11: Angel

12: Ned

13: Angel

14: Ned

15: Angel

16: Ned

17: Angel

18: Ned

19: Angel

20: Ned

21: Angel

22: Ned

23: Angel

24: Ned

25: Angel

26: Ned

27: Angel

28: Ned

29: Angel

30: Ned

31: Angel

32: Ned

33: Angel

34: Ned

Copyright

Contacts Page

Some Authors

PROLOGUE

I cannot believe my father is inside that black plastic box that just came from customs. No way. The box is now sat on top of the table in our sitting-room, and everyone is staring at it. Absolute horror. I don’t know exactly what they expected. A box like any other box. A delivery box. I lift it. It is heavy. A trickle of dust is coming out of one corner. My father’s ashes, I assume. I run a finger through the dust on the table, then I smell it. I’m tempted to lick it, but somehow I feel the others’ growing disapproval. On the lid, in small letters, my father’s name is written.

In a flash, it dawns on me that it could be any name.

Then, suddenly, all of them start running around, setting the table, placing flowers and bonbons and a candle, digging out a portrait of the deceased, and the domestic altar is ready. Later, other things are added: an icon, a cross, my father’s books, a diploma, a medal. My grandmother insists on highlighting my father’s social standing. Mama is pretending to do the housework, concentrating on the details, but actually she is on some other planet. She is trying to see through the dense fog that separates the world of the living from the world of the dead … People start to arrive; they stare at the black box and nod. Everything is so unexpected. Not long ago they were drinking together, and now he was gone.

The death of my father is shocking for many reasons. First of all, he was young, only fifty. Second, he was endowed with a brilliant brain, which is now lost for ever. Third, the tragedy occurred in the butt-end of nowhere, somewhere in America, which makes us all feel even more helpless. Fourth, nobody knows exactly how the tragedy happened, which enshrouds the incident in a sinister aura and fosters all sorts of ludicrous myths. Fifth, these events are, in principle, tragic. Sixth, there are probably many other reasons I cannot think of right now.

Almost an entire year has passed since the fall of Communism … I always thought something like this would happen to him sooner or later if he carried on the way he did … My father, that is, and his drinking. He did carry on, though, drinking like an Olympic champion, and the only thing we could do was to cross our fingers. I had no clue what on earth he was trying to prove the rest of the time. All those integrals, algorithms and theorems he was producing – well, I hadn’t the slightest idea what all that was about. I was never into maths. My maths results were appalling at school. I cannot say that he was helpful either for that matter. He felt pity for me. I felt pity for him, too, for having to deal with this non-gratifying material. In some paradoxical way I was so bad at it and he was so able that, at the end of the day, we found ourselves in the same position. The length of the equation is of no importance if you cannot solve it. The only difference was that I didn’t give a toss, and for him it was a matter of life and death. Fucking integrals – they look like fishhooks. You bite one, and that is the end of you. And who, I wonder, is casting those hooks in the pond called Science to catch the carp?

There comes my brother Nedko, a battered postman’s bag around his shoulders. Last year he couldn’t get into university, so according to some stupid law he had to work for six months before he could take the entrance exams again. The State is looking after the country’s youth so they don’t hang around jobless. I suspect the law will change soon. But right now he has no choice.

I say to him, ‘We have a parcel from America.’

Nedko blinks. Confused. Then he notices the black box and a guilty smile appears on his face. His work for the postal service has turned him into a cynic. His bag is overflowing with letters, newspapers and magazines, and I bet they won’t be reaching their addressees any time soon. It is an unfortunate coincidence that he is responsible for our area, too. It is the reason the letter announcing the tragic arrival of the black box turned up two weeks late.

Nedko is trying to make it up to me and shoves the latest edition of Ogoniek – a liberal Soviet magazine that specializes in publishing blood-curdling revelations – in front of my face. Now, however, I am not in the mood for gossip with a Stalinist twist. I stare at that box, and I wonder how on earth I can be sure that the ashes inside are my father’s and not some tramp’s. I communicate these suspicions to my brother and he shrugs, as if asking where I’d got that crazy idea from. Where indeed? Well, you don’t need to have a fertile imagination to figure that one out. But he seems not to have one. The transportation of the body from the USA to Bulgaria would have cost two thousand dollars, a sum we could never have afforded. The insurance company had been messing about. The university had not been willing to pay. The Bulgarian Embassy had also not been keen on footing the bill for repatriation, so the only remaining option had been cremation. Given the fact my father was an atheist he wouldn’t have minded. So, his ashes travelled as a regular parcel.

A parcel from America.

‘You said that already.’ My brother is frowning.

‘There is a short story with that title’, I continue, ‘by Svetoslav Minkov.’

The story was published in the 1950s in a propaganda journal, and it aimed to expose and discredit the bourgeois value system. A middle-class family has relatives in the States that regularly send them parcels. Transatlantic goodies trigger unbelievable enjoyment and give reason for endless showing-off and commentaries along the lines of how great the West is and how rotten our own light industry is. On one occasion, though, an unusual parcel arrives. The parcel contains a sealed metal box with nothing written on it. When they open it they discover it is full of mysterious dust. They sit down and they wonder, What is this? What is its purpose? In the end the father decides to be brave and puts a spoonful in his coffee. The effect is revitalizing, and they decide that it is some sort of vitamin. They start drinking it for breakfast, and in the meantime they find all sorts of uses for it in their daily lives. When they run out of the miracle substance they decide to write to their relatives and ask for more. But then they receive a letter. This letter was meant to arrive with the parcel, but apparently it ended up in the bag of someone like my brother … In the letter he relatives announce the death of an aunt and that they are sending her ashes to Bulgaria to be buried. Following this the family stops glorifying the West so much.

‘Clever,’ my brother says.

When there is an plane crash everyone rushes to locate the black box. In this box all the navigation data is kept, together with the data for the technical condition of the systems, the crew’s conversations, the orders of the pilot and so on and so forth. The device allows events before the catastrophe on board the plane to be reconstructed and analysed for potential causes. My father’s black box does not contain anything; all the information has been erased, transformed into ashes. Suddenly I realize I did not know him at all. I did not understand his work. I detested his drinking. I trembled in the face of his rage. I loved it when he was away. I was afraid he would not come back, and that is what happened.

One event slips through my memory like a postcard from the afterlife. Wide beach, hotels and palm trees on one side and the Atlantic on the other, dark and threatening. An advertising blimp is navigating the skies, a huge banner, ‘Myrtle Beach’, trailing behind it. We are in America, and the year must be 1986. My father was sent to teach two terms at the University of South Carolina, and our State nobly gave him permission to take his family with him. I was in my third year of university and very keen on emigrating there – on principle, not because I liked the place that much. My father was unwilling. We talk about it on the beach. The only serious conversation we ever had. I do not remember the words. The breakers are muffling them. My mother and brother are walking at some distance ahead of us. I contemplate our shadows galloping next to each other on the sand. He is a tall, well-built – even overweight – man with a big head and short hair. His belt crosses his belly in the middle. I find that funny. I am skinny with a bushy hairstyle. My trousers hang below my waist, just at the point of decency. Two days ago I spotted Aerosmith’s lead vocalist wearing his trousers in just such a fashion on MTV, and I found it extremely chic. My father is explaining why he doesn’t want us to stay in the USA. It is not that we can’t or the thought hasn’t crossed his mind but because there are things far more important than the shops full of goodies. Respect, for example. Man should have a certain weight; an immigrant is always an immigrant, lightweight. Even here, in America. Now they are treating him as an equal, but if he decides to stay here as an immigrant people’s attitudes towards him will change. I know it is difficult to explain, he says as he puts his arm around my shoulder (or he doesn’t; I don’t remember any more). His arguments reach my brain in a highly fragmented way. In fact, I do not care whether we are going to stay or not. The most important thing is to have more than one choice, he continues. To have the guts to say no. An immigrant cannot say no. Then he talks about his students in Bulgaria – the boys, as he calls them. It would not be the same without them. Naturally, he can always keep the regime as an excuse, and everyone will understand. His relationship with the Communists has never been easy. He achieved everything in spite of the regime, which makes his success even more valuable. But even regimes change … I hear him mentioning the name of the Soviet leader Gorbachev, but all my attention is taken up by a girl with a ring through her navel. For the first time I see such a miracle. The ring flashes blindingly on the whiteness of her belly. My jaw hits the floor. I feel myself going back a hundred thousand years down the evolutionary path. What Gorbachev? What perestroika?

My father does not notice anything …

I’m thinking, if you had noticed that ring, man, you could have been somewhere else now, not in this fucking box. Life is not only integrals, hypotenuses and vodka. Now it is too late to preach reason to my father, though. It is too late for the desire to know him better. We can’t even go for a beer together any more. End of story. He is in his box now, comfortably settled, and doesn’t give a damn about anything. I mean his ashes. I do not know about the soul; it could easily be wandering round the States, riding an invisible Harley-Davidson and screaming with joy, ‘I got out! Fuck! Fuck! Fuck!’

But we are here to stay. Literally and metaphorically, we are. To cap it all, the insurance company refuses to pay out on his policy. They insist on DNA tests. But he has already been cremated. The fucking idiots calculated we are too far away to do anything about it. We are about to lose one hundred thousand dollars.

That happened fifteen years ago.

1

ANGEL

Eighty-six kilometres to the final destination, the monitors above the seats informed us. Temperature, minus 15 degrees Celsius; altitude, 3,500 metres. On the screens the map of the western hemisphere emerged. The plane’s trajectory was marked by a white arrow starting in Central Europe, passing over Scotland, crossing the North Atlantic over Iceland, turning towards Labrador and entering the USA at a steep angle similar to that of a ballistic missile. Its point is almost touching the spot labelled New York.

I leaned back in my seat and closed my eyes. I hadn’t slept a wink the whole trip. The luggage racks above my head were loose – it rained bags, clothes, plastic bags. I didn’t understand all the rush. America isn’t going anywhere. It’ll continue to sit on the other side of the ocean and soak up waves of individuals driven by the idea of personal happiness for at least another twenty years. Without noticing, I had dozed off. When I opened my eyes the queue between the seats hadn’t moved. I had no idea how much time had passed. Sullen, sweaty people, bags between their legs, were complaining loudly.

‘What’s going on? Why aren’t they letting us out?’

‘Ladies and gentlemen, there is a minor medical problem on board.’ The pilot’s voice sounded dispirited, like a guy whose plans for the evening have fallen through irreversibly. ‘We ask you to be patient until we have clarification of the circumstances surrounding the incident. We apologize for any inconvenience.’

A minor medical problem! The passengers slumped into seats with glum expressions and began to take out their mobile phones. At the front end of the plane people dressed in brightly coloured biohazard protection suits and gas masks started to appear.

Now we were in for it!

The guilty party behind the commotion was the snotty brat who hadn’t stopped throwing up for the last few hours. Clearly that had aroused suspicions of biological attack. The team milled around the boy feverishly, checking his pulse, his heart, taking blood samples. The mother was sobbing. The father, a Middle Eastern type with a thin greasy lump of hair stuck to his pate, was nervously crushing an empty crisp packet. Beneath the surface of this minimalist gesture however, lay the terror of an ordinary man thrown into the heart of global chaos. From time to time the commander of the flight said something to calm people’s nerves. The guys with gas masks carried suitcases full of equipment back and forth. But things were taking their time. We sat cooling our heels, stress having already given way to bored indifference.

I hadn’t set foot in America since the thing with my father. (I catch myself always referring to ‘the thing with my father’ instead of ‘he died’, ‘passed on’ or ‘kicked the bucket’, as if any word for ‘dead’ would be taboo.) The excitement surrounding my desire to travel across the Atlantic popped like a bubble-gum bubble, sealing my daydreams of emigration within its sticky pink stamp. It took years before I could think of it again. Even then, it was as if some invisible prohibition continued to loom over that part of the world. That didn’t apply to my brother, who had accepted my father’s death with no questions asked. Nedko went to study in the States several months after the tragic accident. He did an MBA, and naturally he stayed there, except for holidays. Then he stopped coming back even for those. Now he worked on Wall Street, and I supposed he had every reason to be pleased with himself. Actually, in some way we both stayed: one in the States, one in Bulgaria. Not that I was complaining. That was the situation. Nobody forced me to stay. I chose for myself.

I had just finished my English degree, and there was a place for me at the university, but I preferred to dedicate myself to business. Times were such. Anyone and everyone was registering firms, buying, selling … At the beginning of the 1990s publishing looked like a way to get rich. There was a hunger for books unavailable until now. People still had money; they were grabbing whatever crossed their path. We sold an inherited property. Half went on my brother’s studies, and the other half I invested in business. I released about a dozen not-bad crime novels, money flowed; I bought myself a secondhand Opel and married young. But the business climate went down the drain, and I ended up in the shit, big time. I continued to churn out a title or two, just to keep up the façade, but I felt it wasn’t going to last. I was also fed up with chasing warehouses and printers or going after various distributors to collect my miserable dues. I was making ends meet translating for other agencies, mainly thrillers and science fiction, which I liked.

The family climate wasn’t all that sunny either. My wife and I didn’t get along, although we’d gone out for a whole year before we took our vows (what a phrase) and got married solemnly in a church with various important people and promises of till death us do part. It is as though that screwed the whole thing up from the start. The box we stuffed ourselves into, that of a happy young couple from a mattress catalogue. In the end the realities of such a life took over. Utter banality. Sex going downhill. She was an artist, but she was bread-winning in some advertising agency where, for no particular reason, they gave her only sausages to draw. She tried to do some covers, but it didn’t work out. But sausages she could do. She even won an award for them once, at some international exhibition, after which she was invited to go to Italy. Let’s get divorced – I don’t remember who said it, but neither party made an attempt to counter it. We didn’t have children, nothing to divide – apart from the opel, and its wheels had been stolen. She gave it to me. And left. Now she’s most likely drawing salami – but for a lot more money.

Everybody scrambled to save themselves, like rats in the bilges of a sinking ship. Most of my friends moved to Ireland, Spain and Germany, even to Portugal, from where, as a rule, the Portuguese themselves are trying to get away. In the end my mother shifted herself, too. She had just retired from the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, where she had worked for over twenty years, with the fabulous pension of about a hundred euros. She went away to take care of some old guy all the way over in Wales. It was set up by some former colleague of hers, who had developed a whole network of carers for old folks in the UK. She’s been there for three years now, in some small town I always forget the name of, famous for its amazing natural beauty and Celtic monuments strewn across the landscape. I’ll stay, she says, as long as I can. She even sent me money after that fiasco with the little penguins. I never had a good feel for children’s literature. But the agent persuaded me that those penguins were a huge hit right across Europe. Ten series with pictures. The rights cost me a fortune, and the printing expenses even more. I printed ten thousand of them, but hardly sold a single one. That was the end of my publishing career. Wherever I looked, only dust, idiocy, stray mongrels and hopelessness …

Then I asked myself why I didn’t shift my ass somewhere. I mean seriously, not like half the Bulgarian population who like the idea after they puncture a tyre in one of the countless craters in the roads. It took me almost a year to motivate myself. Maybe because I wasn’t dying from hunger – after all, I had a roof over my head, when I felt like a screw I always found someone, and when I felt like a drink I was never left dry. I often lied to myself that things weren’t all that bad. But I knew that path only leads further and further down the road to physical and mental degeneration, and I wasn’t even forty, and my whole life was ahead of me.

At least that’s what they say.

And, yes, I played the lottery with at least a million fellow potatoes looking for more fertile ground. I didn’t believe anything would come of it, bearing in mind my brother’s experience. He would send envelopes like a madman until finally the company he worked for sorted the work permit for him. But the lottery is a national sport in Bulgaria. Play, it might happen. When you do win, though, everything goes to hell. One powerful imperative sweeps away your former life: you’ve been chosen. Here fate gets involved. You’ve been given a chance, the door has been left ajar for you and whether you go in is entirely up to you. Everyone deserves happiness. And now there’s no way out. If you don’t answer Uncle Sam’s bugle you’ll be whinging to the grave. The ulcer of doubt will eat away inside you even if everything turns out fine. And if, God forbid, your life takes a downturn, you’ll be pulling your hair out thinking of your wasted chance. The clash with domestic reality, so routine and unavoidable until now, suddenly acquires tragic dimensions. You screwed upagain, you idiot will ring in your head like the echo of a nail being hammered. You screwed up again.

My brother was frequently away on some project, and his apartment sits empty for most of the year. So it’s no problem for him to accommodate me, at least to begin with. If I could get myself out of here, of course …

The air-conditioning and air-purification systems had been switched off to slow the spread of the suspected infection. The air inside the plane was hot and heavy, saturated with the smell of bodily vapours. Some of the passengers held napkins to their faces. Just my luck. When the gates are finally opening for you, the Green Card is in your pocket and you, so to speak, are in the full pocket of America; some sneaky virus could be breaking down the walls of your cells to remind you that the lottery of life and the Diversity Immigrant Visa Program have nothing in common.

I imagined how I’d be spending the following months in quarantine in some secret camp, outside US borders, behind electrified barbed wire. Under the pretext of curing us, some murky department of the CIA that deals with biological investigation conducts macabre experiments on some of the detainees from the more second-rate countries. My body is covered with ulcers, and I’m dying in unbelievable agony. Victim of international terror. As far as I know, in this case insurance policies generally don’t apply. They quickly cremate my remains to cover the traces. One fine day my brother receives my ashes in a black plastic box like the one in which my father arrived.

Welcome to America, dude.

2

NED

For a long time I thought I was happy – or, if not exactly happy, then at least content with my life. Objectively speaking, I am not lacking for anything. I am officially in the category of Successful Bulgarians Abroad, SBA. Unofficially, though, things are slightly different. Happy I am not; neither am I particularly content. The only consolation left is that I am an SBA – which, unfortunately, is not enough. In this life one needs something more than the jealousy of the NSAB, the Non-Successful Asses stuck in Bulgaria.

And that something more is what I lack.

I think I always knew this but stubbornly hid my head in the sand. I tried to look at the situation positively, like they taught us at university. When your salary jumps around 10 per cent a year that’s not particularly difficult. You progress through the hierarchy. You learn new things. You travel. Until one day things start to repeat themselves. As do the destinations. The lavish evenings on your company’s credit don’t do it for you any more. Neither do the luxury hotels. Nor the flights in first class. Imperceptibly, but irreversibly, you begin to understand.

You’ve reached the peak of your possibilities.

The ceiling is as transparent as a glass floor. You see the people walking above you clearly, you even hear the squeak of their two-thousand-dollar shoes, you can look up their wives’ skirts as much as you like, but you can’t join them up there. I don’t fool myself any longer. The ladder I was climbing ends beneath their soles. When you understand that at fifty it probably doesn’t matter. You’ve already flowed through the system’s sewers, and you float around the edges until the tide erases the memory of you like it would an oil spill.

‘Do you feel successful?’

The question is launched by a Bulgarian journalist, who is making a series of ‘portraits’ dedicated to the phenomenon of SBAs for a big Bulgarian newspaper. I have no idea how she got my details. She mentions the name of an old acquaintance of mine who went back two years ago to become a big shot. But I reckon her hidden agenda is to grab some desperately lonely office zombie and get a ring on her finger. It’s not gonna be me, even though she’s a looker. Success, I hold forth, is relative. There are different levels of success. And things of that sort …

This year, for the first time, I didn’t get a pay rise. Actually, to be completely honest, they even cut half a per cent. That’s a measly fifteen hundred less a year, but it’s the principle that counts. Of course, I’m not the only one who’s been hit. Most senior employees received lighter wage packets. Official explanation: we are overpaid. And the worsened economic climate. We all know that. I don’t see how my half a per cent will help a company with an annual turnover of two billion, though. More like they’re testing us. Won’t we give in to our anger and disappointment? Won’t someone slam the door behind him? Nothing of the sort happens. We drag our sour faces around, swear through our teeth, but actually we are all dead happy, me included, that we haven’t been given the push. The murky waters of unemployment are rising daily. Nobody’s ready to throw himself in to save his amour propre.

Yuppie sounds glamorous, but only while you can pay your rent. Unfortunately it’s too late to persuade my brother that now is not the most appropriate time to come to America. Any comment in that direction will be seen as an attempt to avoid my familial responsibilities. Angel, or Ango as everyone calls him, has won the Green Card lottery. He played; he won. I took part, too, and not just once. Didn’t have any luck, though. Whatever. Ango-boy has to hang around here at least a few months a year otherwise he will lose his status. A Green Card can’t make anyone’s problems disappear like waving some magic wand, but to lose it would be just as crazy as believing it could.

Ango-boy also wants to be an SBA. I can’t blame him, of course. Essentially, Bulgarians can be divided into three categories: SBAs and NSABs, as mentioned earlier, and TBAs, Thieving Bulgarian Asses, who cause the misery and exile of the other two groups. Any attempt to formulate subgroups or in-between categories smells to me of opportunism. But a logical question crops up: aren’t there any unsuccessful Bulgarians abroad? Well, none that I know of. All of them boast that they are successful, even hyper-successful – how they gorge great handfuls from the cornucopia and drink directly from the fountains of heaven. The rest end up quietly back in Bulgaria. So they are NSABs again. Following the same logic there are no successful Bulgarians in Bulgaria. If you believe their stories, even those who enjoy relative abundance are actually balancing on the edge of misery; their existence is woven from insecurities and mishaps. As for the future, there is no such thing. The truly successful do not hang around for long; they go abroad to join the ranks of SBAs. Those of them who still stay often prove to be the stupidest TBAs.

My brother’s arrival fills me with joy and worry at the same time. I’ve been living alone for three years now, and I’m starting to get fed up with it. On the other hand, it’s not that bad. I don’t have to accommodate anyone. Most of my friends got married ages ago, some are already divorced and remarried, others cohabit … There’s no reason to rush. Women are, as a rule, like leeches, so I believe. To get together with a woman just because that’s expected is a guaranteed recipe for headaches. That’s one of the reasons I avoid going back to Bulgaria. The moment they see you’re an SBA, in good shape and single, something happens to them. It’s like they go crazy and fly at you from all sides; they show their goods and try to snare you emotionally. They wait for you to put a foot wrong and, bang, they put you in harness amid the victorious howls of the entire horde of NSABs, all jumping around you with their wooden wine vessels and traditionally made towels, like Native Americans dancing around the cadaver of a noble deer.

No, thanks.

Some, of course, go back to Bulgaria just to shoot their load. Not me. Not for a screw. I can have it whenever I want in America: (a) there exists the institution of paid sex; (b) the offices in Midtown overflow with desperate ambitious bitches with polyvalent vaginas. And all that pours on to the streets on Friday night. No problem picking one of those up and having a sex life. Provided that they don’t sleep over, naturally. If they start to stay, it’s over! Women’s bodies release a poison that makes men dependent on them; that was my ex Beatrix’s theory. We split up three years ago. Actually, split up is a bit over the top because we never spent more than a week together. She lived in Toronto. We met on a management course in Florida, where some Dr Kandzeburo Oe enlightened us to the secrets of the Six Sigma way – at the time an avant-garde method for extrapolating profits. I guess I liked her, liked her a lot. From time to time Beatrix hopped over to New York, where, of course, she slept over at mine. Then she threw it all in and went to South America. She was trying to persuade me to go with her, to join some newly formed commune somewhere along the Amazon. Not on your life. Abandon the civilized to run off and chase the wild? Beatrix never did get the meaning of that Balkan idiom. At that time I still believed I could pile up enough money to retire without worries at forty-four and enjoy life.

‘Forget it.’ She waved a hand. ‘It’s not gonna happen.’

And she put her enormous rucksack on her shoulders with some funny little shiny pan dangling off the bottom. Sometimes – in truth, more and more often – I miss her. The poison of her fleshy pale body with its pointy breasts apparently worked its way deep into me.

Ango’s attitude to women is quite different – and that’s precisely what worries me. He is one of those men who have nothing against women staying. He always wanted to get married, always had some female creature hanging around him. I have the nasty feeling something like that might happen here, too. He’ll install some woman in the house. I can imagine myself coming back from a business trip and finding them banging on the sofa. Her breasts are sticking out from underneath the sheet, on her shoulder a tattoo of some sinister figure. The woman installs herself. My brother cooks. We eat together. Sleep together. The woman brings a girlfriend. We swap them. It turns out that one of them has AIDS. The sink is overflowing with dirty cups and dishes. A child is born. My bank account is in the red. I quietly cut my wrists in the basement, crouched between the washing machine and the tumble drier, and stare at my runny HIV-contaminated blood as it trickles into the drain and forms a little whirlpool. My ashes arrive in Sofia in a black plastic box like the one in which my father arrived …

3

ANGEL

‘You have hairs in your nose.’

‘Excuse me?’ I leaned over the table.

‘You have hairs in your nose.’ He stared at me fixedly.

My brother is a whole six years younger than me but doesn’t look it. He’s smartly dressed and smells of expensive eau-de-Cologne. His hair is slicked back and his ears have somehow mysteriously drawn closer to his skull. Ned’s got nothing to do with Nedko the postman; Ned’s a guy you can rely on.

‘Everyone’s got hairs in his nose.’

‘But yours are sticking out.’

What a cheeky bastard! Is that all he’s got to say to me? After four years. Instinctively I touched my nostrils. I came across a small clump.

‘Big deal.’

‘If you want to integrate you’d better remove them.’

‘Is that the most important thing?’

‘It depends. Sometimes first impressions count.’

‘Don’t you worry.’ I poured myself more beer. ‘I’ll manage.’

‘Chance is chance. Image is image.’

We were in an Indian restaurant on Columbus Avenue, not far from my brother’s den. The street split the crenellated relief of New York like a runway, disappearing into the violet-stained sky. The sun had vanished ages ago, but the city continues to radiate heat. I had landed exactly six hours ago, three of which had been spent on the plane because of suspicions of an on-board epidemic. But, after carrying out all the tests, they apparently concluded that we weren’t such a big threat to the security of the USA, and they let us disembark. While waiting, my brother had been hanging around the airport, having a further opportunity to think about the reality of my arrival from all possible angles. As far as I was concerned what had happened was an omen. There was a contagion on board, but the source was not the snotty boy. The virus had nested inside me. Far more dangerous than anthrax or the plague, undetectable with microscopes and chemical reactions: the failure virus.

‘So, now that you are in America, what do you plan to do?’

I hadn’t closed my eyes for the whole flight, my body was yearning for sleep, but the time difference was keeping me awake.

‘I’ve got an interview on Tuesday,’ I said with a touch of pride.

Before I left I got in touch with an employment agency that was finding work for people with legal documents. They had arranged several interviews for me.

‘What’s the job?’ My brother got interested.

‘Supervisor in some fast-food place.’

‘You have to start somewhere,’ Nedko – or Ned, as they called him now – pointed out tactfully

I scooped up some sauce with the end of the naan and took a bite. Then masterfully tipped the rest of my beer into my mouth. My tongue sizzled like a coal.

‘You have business experience,’ my brother pointed out. ‘That’s appreciated here.’

He was looking at me intently, as though searching for more defects on my face.

‘To hell with that experience! I want to turn over a new leaf. Another beer!’ I waved to the waiter.

The mantra of losers

Turn over a new page

Start from scratch

Become a new man

Without noticing I had started repeating it.

Ned lived five minutes from Central Park in an old brownstone built from reddish bricks. The apartment – on which he blew just over two thousand dollars a month – was on the fourth floor. The steep staircase was covered with thick brown carpeting which had soaked up a huge variety of stains. It occurred to me that if you tumbled down drunk it would probably soften the impact … The air conditioner had been left on; a pleasant coolness blew over me. The living space comprises an enormous lounge, bedroom and bathroom. Sparsely furnished, functional, 1970s style. Reddish parquet, a rug with big squares, some posters of abstract expressionists. At one end of the lounge there was a lavish wooden breakfast bar scented with bourbon and tobacco.

I’d live here until I find my feet. How long could that take?

My brother popped up from the bathroom, grinning from ear to ear, waiving some funny gadget, something between a vibrator and an electric shaver.

‘What’s that?’ I had a bad feeling.

‘A gift! A very useful gadget,’ he assured me as he removed the cover from the metal tip. ‘Removes nasal hair. Here you go.’

CONAIR. Supreme nose-hair remover with a unique rotating head.

‘What do you think you’re doing with that filthy gadget? You can shove it in yours!’

‘Easy, buddy! You’ll get use to it. You might even like it.’

He switched on and lifted it towards my face. The head vibrated, and the blades glinted.

‘Get off.’ I stopped his hand.

Making a show of it, I poured myself a full glass of bourbon from his reserves and slumped in front of the television. Started channel-surfing. Came across some show. Two rabid men were giving it some. Between them stood two gorillas ready to separate them. The presenter observed them with an unhealthy interest, while the public cried, ‘Jerry, Jerry …’ The men are brothers. One of them is screwing the other’s girlfriend while he is slaving away at work for ten hours. Why are you doing this to me? I love her! Because I hate you! You think you’re better than me! The bitch’s weeping ‘cause she felt neglected. The public: Booooo! Jerry: Aren’t you a bit uncomfortable doing it with his brother of all people? But he has a soul …

‘He gives them piles of cash, I bet, to turn themselves into monkeys?’ I started getting interested.

‘Sure he does,’ Ned nodded.

‘You don’t have a girlfriend hidden in here somewhere, do you?’

‘Only a brother …’ Ned giggled.

‘Hang on,’ I looked around suspiciously, ‘you really don’t have a girlfriend?’

‘No, I don’t have a steady one, is what I mean. At the minute.’

‘But you do date women, don’t you?’

‘So far …’ He yawned.

The next day, Monday, my brother had to fly to Detroit at half past seven. I remained staring at the television for a while, sound down. There was a couple on the stage, husband and wife. The man confessed he had a transvestite lover. ‘Jerry, Jerry …’ the public cried. That thing could never happen in my poor tiny country, I said to myself. If you appeared on television and declared in front of the world that you were screwing your sister under the nose of her boyfriend, people would point at you for the rest of your life. Here you simply disappeared. You grabbed a few thousand, and you floated back into the total anonymity from which you’d come.

If you’re nobody, it occurred to me, you can do anything.

Jerry Springer glamorously summarized the bitter truth of human nature and launched an appeal for traditional values. The backdrop for the show spoke for itself – a narrow street, cluttered with rubbish bins, leading nowhere. Against this came a polite invitation, If you are a prostitute and you have a story to tell, call the following number … I took a few more mouthfuls straight from the bottle, pulled out the sofa-bed and got in.

4

NED

I pluck the newly sprouted hairs from my nose. With tweezers for greater precision. The days when I shot off to work, buttoned up in a suit and tie, are long behind me. I can now allow myself a more casual style. The official explanation is that it creates a more ‘team-friendly’ atmosphere, a concept particularly popular with middle management. After so many years, though, it seems to me that the wretched suit has soaked into me in the same way as the uniform is stamped on the military. I still wear it even when I go to the beach. I think the bosses understand that perfectly and observe all efforts towards liberalization of the corporate dress code with a kind of permissive irony.

The cylindrical headquarters of Silvertape is situated in one of the endless suburbs of Detroit. The security guard waves at me nonchalantly. My team are already there. Melissa, the shrimp, Vayapee, the sly, and Dexter, the crustacean. I catch them clustered in front of one of the computers. They look excited and guilty, like they’ve been looking at a gang-rape website.

‘So, are you ready?’

‘Yes, sir!’

‘Let’s show them what we can do.’

The hall slowly fills up with people. The bosses of Silvertape take their places in the front row. I’ve done it hundreds of times, but despite that I am still a bit edgy. Mainly hoping the technical equipment does not crash, as usually happens at the most critical moment. I think human brains generate some field or waves that affect the equipment. So stay cool to avoid unnecessary worries. My team is fussing around me.

I stick out in front of the brightly lit screen, behind a narrow glass-and-metal rostrum. The greyish-black corporate audience follows the red dot from my laser pen, hypnotized. The slides change with an oily click. Tables, charts, diagrams whizz past. I play God – I make units redundant, swap departments, merge whole structures. The presentation is the summit of many weeks’ work. I lead a small team of three assistants – skilful, cunning brown-nosers. We are optimizing the marketing structure of Silvertape, the biggest producer of food-wrap in North America – maybe in the world. The employees openly hate us, but they’re afraid of us. Substantial cuts are about to take place. I think that’s the reason they called us in. Business needs transference. When Bob and Joe lose their jobs someone must take the blame. And the best candidate for that is the bad white guy with the Eastern European accent.

‘I come from far away, and I’m not here to stay’ is the consultant’s slogan.

Click-click, windows open, diagrams appear, multi-coloured headlines run across, some little men run around … Did I overdo it with the animation? To judge by the faces in the front row the show is a success. I preach the gospel of the market economy wholeheartedly. From time to time I make a carefully balanced joke.

At one end of the hall I spot a burly guy in a checked shirt, baseball cap and a longish black sports bag. I’ve met him before, in a suit, though. Bruce is the head of a superfluous unit of seven people that mirrors the work of at least two other departments. With the unerring instinct of a long-term employee he can sense his unhappy destiny, and since I arrived he has been making desperate attempts to convince me of his effectiveness. He has been swamping me with reports, propositions and analyses that inevitably end up in the shredder. His face is scarlet and sweaty, as if he has run here from home. I sense the rage seeping out of every pore. Oh, yes, I know why he’s got a grudge. Against me, against the company, against the whole system. You work like an animal, and in the end you’re shafted from every direction. The television is full of stories like that. Dude goes rogue, grabs a gun and heads out to spread justice.

Everyone’s eyes are glued to the screen. I don’t stop chattering. I try to avoid Bruce’s scarlet face, although I sense its heat in the periphery of my vision. The short clip is showing a big pair of scissors cutting away the useless departments. The sound effect is like a metallic snap.

Snap-snap. Bruce is in the trash.

Snap-snap. One in the barrel.

As can be seen in Table 7, the profits for the last quarter have been made mainly in the direct sales departments …

The audience’s composure cracks like thin ice. Somebody starts laughing in the dimmed light; after him, another. The giggles crawl in all directions. Huh, what did I say? I fix my eyes on the laptop’s screen, from where I am managing my presentation. In the centre of the tables twinkles a strange animated GIF. I turn my head towards the big screen, where a pop-eyed female is sucking some anonymous dick. Instinctively I cue the next slide. My ears are buzzing with adrenaline, but I continue, unembarrassed. If we compare the relative effectiveness of the production lines …

Silence. On the faces of those present passes a spasm as if, on command, they have bitten down on glass ampoules filled with potassium cyanide. Then it explodes … The laughter whips me like a shockwave. I squeeze the edges of the glass table. From the monitor, the white-browed Hugh Merit, chairman of the board of directors, is looking out, penis erect and naked except for a pair of red fishnet stockings. The same monstrous image, but magnified many times, is projecting itself on the screen behind me.

The lights are on. The hall is buzzing like a beehive. I spy the baseball cap, which is sneaking out with its evil bag. My so-called team has hidden itself in the corners. I’m alone.

‘You dirty bastard. Is that why we’re paying you three hundred dollars an hour? Is that all you’ve managed to create after all these weeks? You parasites!’

‘Hugh, Hugh, calm down …’ Ben and Miller, two of the directors, are pulling him back. ‘And you, young man, try to come up with some plausible explanation.’

‘Obviously sabotage …’

‘Obviously! And who has an interest in sabotaging the presentation that way?’

Who indeed? I turn around to face the agitated crowd.

‘Gentlemen, you are about to throw some fifteen hundred people out on the street. At least two hundred of them have access to the company intranet, and they certainly have an excess of motivation … You know, gentlemen, I think we got lucky here –’

‘What?’

‘Really,’ I begin with even more assurance, ‘this is nothing. An unpleasant but essentially harmless incident. Just imagine if someone had stormed in with a machine gun or a bag full of explosives? Where would we be now?’

‘Ummm …’ Ben and Miller scratch their heads. ‘We will conduct an internal investigation.’

‘So will I.’

Brabury’s has more than a hundred offices scattered across the USA and abroad, but there are two main rivals among them, the central one in New York and the Chicago branch. Between them there is an ancient feud and a secret fight for supremacy. The people from the Windy City cannot calmly accept our leadership. They are convinced that they generate enough profits to be independent. There are more of us, and we receive bigger salaries, so it seems to them we are eating what they earn. And when some self-assured asshole from New York lands on their heads they try with all the means at their disposal to break his legs. I was warned not to annoy them. I tried. Especially during the first few weeks. I even organized a picnic. You think you’ve created a small, united team. But at the end of the day you’re shafted. I can only guess at who is responsible: Melissa, Vayapee, Dexter? I have no evidence other than their guilty looks. Or maybe they all worked together to paste Hugh Merit’s head on to the body of an unknown transvestite. They made a pretty good job of it. Or maybe it was a hidden-camera gig.

I’ll probably never know.

I finish my presentation in a small meeting-room on the sixteenth floor with reinforced security measures. I use an older graphics version. It comes across as a wooden, unartistic spectacle with an emphasis on the dry statistics. There are no questions. I make Dexter and Vayapee take notes and present written reports on all the problems raised. Speaking through my teeth I order Melissa to prepare a detailed internal audit on the progress of the project through its various phases. I really hope that will poison their week. I want to call them aside before we part, to tell them how ugly, stupid and pathetic they are, how minimal their chances of success are and how, no matter how hard they try, they’ll be thrown out with the rubbish in the end after being drained to the last drop.

After the presentation there is something like a stand-up working lunch, which passes in a glacial atmosphere. Hugh Merit leaves without saying goodbye to any of our team. Logical. Only then the mood crawls up from zero. I even receive some secret pats on my back. The only thing I want, though, is to get back to New York as soon as possible.