13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

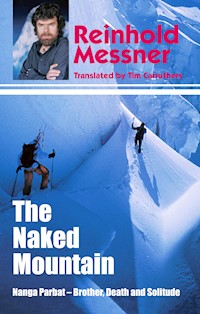

The ascent of Nanga Parbat in 1970 marked the beginning of Reinhold Messner's remarkable career in Himalayan climbing. But this expedition has always been shrouded in controversy and mystery; his brother Gunther, who accompanied him, met his death on the mountain. In The Naked Mountain Messner gives his side of the story in full for the first time. This most personal account is a story of death and survival and for those who want to understand what is the force that drives Messner on, this book is the key. 'Nothing if not passionate, Messner writes of the Himalyan experience with a nearly mystical fervour. His description of catastrophe at high altitude is page-turning' Rock & Ice. 'A gripping piece of writing ...the translation reads like a good thriller, drawing the reader back through historical epics; treading the footsteps of climbers right on the edge of things' Scottish Mountaineer.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

ReinholdMessner

TheNakedMountain

Nanga Parbat –

Brother, Death and Solitude

Translated by Tim Carruthers

The Crowood Press

Title of the original German edition:

Die Nackte Berg

© 2002 Piper Verlag GmbH, München, Germany

English edition first published in 2003 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2016

English translation © The Crowood Press Ltd 2003

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 78500 213 7

To Günther, my climbing partner and my brother.

Günther Messner, 1970

Convoy of climbers and porters on a Himalayan approach march.

Contents

Map

The Film in My Head

Introduction: Nanga Parbat

The Most Difficult Climb of My Life

I.My Brother, His Death and My Madness

Günther – Lost but not Forgotten

II.The Crowning Glory: the Himalaya

The First Attempt

The Second Attempt

III.The Death of Willy Merkl

The Tragedy

IV.The Legacy

Herrligkoffer’s Obsession

Buhl’s Solo Climb

V.Hermann Buhl’s Fury

Return and Isolation

The Trick with the Rhetorical ‘We’

VI.The Mountain and Its Shadow

Nanga Parbat as Therapy

Nanga Parbat as a Daydream

VII.Nanga Parbat at Any Price

Departure for Nanga Parbat

Against the Wall

Snowed in at Camp 3

VIII.Worlds Apart

Doubts About the Leadership

Back to Base Camp

Excursion to Heran Peak

IX.Intrigue or Misunderstanding?

Life at Base Camp

The Final Assualt

Into the Death Zone

X.The Decision

The Red Rocket

The Key to the Summit

Two Worlds – One Goal

Günther’s Decision

The Summit

The Descent Begins

Bivouac

No Rescue

XI.Lost

Desperate Measures

Descent Into the Unknown

The Third Man

Second Bivouac

No Reply

The Avalanche

Return Through the Diamir Valley

XII.Death and Rebirth

Hallucinations

The First People

Nagaton

Ser

Murderer or Saviour?

Diamiroi

In the Indus Valley

XIII.The Summit Triumph

Triumph and Tragedy

Reunion with Herrligkoffer

XIV.Epilogue

Inconsistencies

XV.Mountain of Destiny

Günther’s Climbing Journals

Years Later

Bibliography

Avalanche on the Diamir Face of Nanga Parbat.

Nanga Parbat from the west with the Diamir Face and the upper Diamir Valley.

Nanga from the east with Hermann Buhl’s 1953 route; to the left is the Rupal Face.

In 1856, Adolf Schlagintweit stood at the foot of the southern precipice of this mountain. In terms of size and steepness there is perhaps no other mountain face on Earth that can compare. I dare to make this statement since Marcel Kurz, one of those best acquainted with the high mountains of the world, shares this view. From the valley floor at Tarshing to the summit it is 5200m of vertical height. As established by Finsterwalder during observations conducted on the 1934 expedition, the average angle of the South-East Face is 47.5 degrees, and on the upper section 68 degrees. Steep indeed!

Paul Bauer

This dark mountain realm with all its hidden threats lies at the end of the source of all that is living.

A.F. Mummery

The Film in My Head

The defining experience of my life happened a long time ago in a faraway place. It was in the Himalaya, on Nanga Parbat, that I experienced the kind of expanded state of being that occurs on two levels of consciousness, the kind that can easily lead you to believe that the brain is suffering from insane delusions. For it was there that I experienced, quite clearly, how Life and Death first occurred and how they then – almost simultaneously – became part of my biography. What happened all those years ago remains in my memory as the story of my own death and at one and the same time the impossible story of my survival.

The traverse of Nanga Parbat from south to north-west in 1970 was, for me, far more than the crossing of a definite line in the geographical sense. It was like a border crossing from this world to the next, from life to death, from death to life.

I am recounting the whole story in detail now, in order to include all those who are a part of what happened and the pre-history that, at a subconscious level, was a part of my experience from the very start.

Back then, I was completely alone for a week – inconsolable, despairing, without hope – as I made my way down into the Diamir Valley. I had suffered, I was badly frostbitten. I had died. Half starved, my soul laid bare, I finally returned to the company of human kind. When I finally saw all the others again, the people I had expected to rescue me, Nanga Parbat seemed far away, an untouched peak above the clouds – the Naked Mountain. My brother, too, was far away. But where exactly was I? As I looked around the Indus Valley, I felt longing, fear and pain. I was still here.

The Mazeno Ridge and Nanga Parbat from the south. The Messner brothers’ route is on the right of picture.

When I look back at these events today I see myself both as the victim and the dispassionate observer of the tragedy that befell us. As if I have passed through several stages of consciousness, my survival on Nanga Parbat lives on within me, an intimate interplay between being there and a faroff detachment from the events. I now wish to tell the story of that Nanga Parbat expedition in the same way that I experienced it, as an interplay between pure observation and a story as I experienced it, a shocking tragedy that marked the beginning of my identity as a man who tried to push the boundaries.

The 4000m Diamir Face of Nanga Parbat.

Up there in the summit region, driven only by the will to survive, I frequently saw myself from a distance, as if my spirit had become detached from my body. Then I experienced again how reason and intellect would process emotions and incorporate them into my being, finally to create a feeling of unshakeable certainty. Thus it was that feelings of helplessness and despair became my destiny and a part of my life story.

I do not question what it is that creates this ability to experience events in this way; I am more concerned with the self that was born out of this process. I am telling a story that goes far beyond my own life and I write it down here as I experienced it then, as observer and protagonist at one and the same time. My theme explores how external sensual stimuli and the worry of survival create fear and how a person reacts when caught between the twin forces of life and death.

Without consciously wishing to interpret how things occurred in the way they did, I write of the way I experienced my survival and the split between being part of those events and standing apart from them. My brain registered everything that happened in exact detail – the external and the emotional, the physical and the mental processes – as if there were intervals or spaces between the feeling, the realization and the storing of the information.

Although in the final instance these mental leaps were concentrated purely on the human organism’s instinct to preserve life – slowed down, perhaps, by the imminent possibility of dying and the lack of oxygen – their effect on my conscious mind was similar to a state of schizophrenia, as perceptions and emotions faced each other like images of the sun and the moon.

In exactly the same way that feelings arise from external sensual stimuli and the experience later remains as a ‘film in the head’, my story shifts from the first to the third person during the critical phase. Splicing the emotions of the spectator into my ‘film in the head’ is my attempt to clarify how the conscious self arises when death is close.

Introduction

Nanga Parbat

Nanga in the early morning light, viewed from the east.

The Nanga Parbat massif forces the Indus to change course and head off at 90 degrees to the south on its 2000km journey from Mount Kailas to the Indian Ocean.

Hermann Schäfer

It was around the middle of the 19th century that Nanga Parbat, the 8125m high western cornerstone of the Himalaya, was first ‘discovered’ by Europeans. Adolf Schlagintweit, the Munich-born Asian explorer and researcher, had penetrated as far as the foothills of the Himalaya on his travels and had seen Nanga Parbat from the south. A little while later he was murdered in Kashgar. The fateful history of Nanga Parbat had begun…

Reinhold Messner

The South Face of Nanga Parbat, viewed from the Dusai Plateau.

The Most Difficult Climb of My Life

When Adolf Schlagintweit asked the locals about the name of the great mountain he had seen they replied ‘Diámar’ and ‘Nánga Parbat’. Translated from the Urdu, the names mean ‘King of the Mountains’ and ‘the Naked Mountain’.

When, seventy-eight years later, in 1934, the geographer and mountaineer Richard Finsterwalder was able to study the mountain from all sides and carry out an exact survey, he simply referred to it as ‘Nanga’, in common with most climbers of the time. Finsterwalder, then a professor in Munich, was impressed: ‘There is a 7000m height difference between the ice-encrusted peak of Nanga and the Indus, whose melancholy waters wind their turbulent way along the foot of the mountain. There are probably few places on this Earth where nature displays herself to mankind in such a grandiose and varied manner and reveals so much to us of her secrets and wonders.’ He went on: ‘Nanga Parbat is constructed like a series of storeys, with deeply riven valleys and gloomy gorges scored deep into its mighty body.’

In a similar way to Alexander von Humboldt’s description of Chimborazo, the work of Schlagintweit, Finsterwalder and, later, Dyhrenfurth has shaped the popular image of Nanga Parbat. With information gained from their botanical, geological and mountaineering explorations they awakened a similar degree of curiosity about the mountain.

Down in the Diamir Valley. Mummery passed this way in 1895. In 1970 Reinhold Messner lay here injured, unable to walk.

The Mazeno Ridge and Nanga Parbat (left), scene of the 1895 and 1970 tragedies.

Günther Oskar Dyhrenfurth believed that the Nanga Parbat group was a single, homogenous massif of gneiss and, like Finsterwalder before him, he gave considerable thought to the potential routes of ascent. Dyhrenfurth was effusive about the view he had of the mountain and excited by the idea of the peak as a mountaineering objective. ‘The summit is covered in glistening firn snow, the ridges and faces plastered in ice. Beneath these is a belt of alpine pastures and mighty forests that drop down to the glaciers below. Lower down the forests stop suddenly and the vegetation grows sparser. It is hot and dry here and we find isolated little settlements with artificial irrigation. Lower still the heat has killed off all life and right at the bottom of the mountain, the last 1500m down to the Indus, is a fearful desert region.’

For explorers and mountaineers alike, the mountain appeared to be an objective full of secrets and mystery. For half a century it represented the greatest possible challenge for the elite amongst German-speaking mountaineers – it became their Holy Grail.

‘When German climbers set off to remotest Asia to conquer this peak they would not be true German climbers if merely standing on the summit were enough for them’, Finsterwalder suggests. ‘If they failed to bring home with them anything of the wonder and mystery of the Himalayas then all the trials and tribulations encountered on the way to this Holy Grail of mountaineering would be for nothing.’

1934. Himalaya. Nanga Parbat. For the first time, five climbers and eleven Sherpas pushed the route as far as the Silver Plateau. Following the route reconnoitred in 1932 they almost got as far as the summit. The leader of this dangerous enterprise was one Willy Merkl; the mood one of expectation and concern. A short while before, Alfred Drexel had died of altitude-induced pulmonary oedema. The team was feeling the pressure. Suddenly the mist closed in and the wind blew up. The snow storm lasted two weeks. The descent was catastrophic: Uli Wieland, Willo Welzenbach, the expedition leader Merkl and six Sherpas lost their lives.

When Karl Maria Herrligkoffer, a younger half brother of Merkl, learned of the tragedy he vowed to continue ‘the battle for Nanga Parbat’ as a legacy and memorial to his late brother. Willy Merkl was his role model and the heroic death of the Germans on Nanga Parbat provided the impetus for him as he strove to realize the ideals that they had aspired to. For Herrligkoffer, this far-off peak in the Himalayas soon became an obsession.

The Rakhiot Face of Nanga Parbat with the Silver Saddle and the Silver Plateau. The summit is on the far right.

The locals have two names for their mountain: Nanga Parbat, ‘the Naked Mountain’ and Diamir, ‘King of the Mountains’. Herrligkoffer viewed the mountain as his own personal holy crusade. This unclimbed peak became the objective to which he would dedicate his whole life. This was Nanga Parbat, the mountain of destiny.

Herrligkoffer published the diaries of Willy Merkl and came to identify more and more closely with the lifetime ambition of his brother. In order to redeem his silent pledge he wished to travel to the Naked Mountain himself. Working like a man possessed, he found the financial means and the first-rate mountaineers he needed, acquired the necessary mountaineering permit and organized all the travel arrangements and equipment. In 1953 he undertook his first journey to the Himalaya, leading a group of climbers to Nanga Parbat, the Holy Grail of German mountaineering. The venture was known as the Willy Merkl Memorial Expedition.

View from the Silver Plateau back to the Silver Saddle with the Karakorum in the distance.

Hermann Buhl finally succeeded in making the first ascent of the mountain, against the express wishes of Herrligkoffer. Pepped up by the drug Pervitin he managed 1300m of ascent in a single day, reaching the summit alone on the evening of 3 July 1953. After surviving a night out in the open, he managed to descend safely. With his last ounces of strength he reached the camp below the Silver Saddle, where the two colleagues who had supported him on his summit bid were waiting. Herrligkoffer, however, who as leader of the expedition had previously ordered retreat from the mountain from his position at Base Camp, was in an emotional quandary. His feelings wavered between joy at the success and disappointment in the manner in which it was achieved. He felt he had been betrayed by the three men, who had acted against his instructions, outshone by Buhl, who had acted selfishly on his own account, and passed over by the world media. Perhaps he also felt cheated of the ‘unconditional’ ascent that the voice of his dead brother demanded of him?

The summit ridge of Chogolisa in the Karakorum, Buhl’s last objective.

A group of porters on the Abruzzi Glacier in the Karakorum. Broad Peak, Buhl’s second 8000m peak, is on the left of the picture.

Back in Europe, doubts arose as to the validity of Buhl’s summit bid. Herligkoffer even initiated legal proceedings against the ‘victorious summiteer’ at a later date. In Herligkoffer’s eyes, Buhl remained until his death the ‘defiler of the pure ideal’.

For Herligkoffer it was the myth of Nanga Parbat that exerted such a magical power and allure. He felt that to capture the prize that rightly belonged to his brother, yet had proved impossible for him to achieve, was his destiny. More and more climbers made the pilgrimage to the ‘King of the Mountains’ with this obsessive man. It was not that the mountain needed them, they needed the mountain: for their ambitions, their dreams, their hubris. Karl Maria Herrligkoffer had stylized the ‘Naked Mountain’, elevating it to a high ideal.

The Rupal Face and photos of the journey: Alice von Hobe, Karl Herrligkoffer, Reinhold Messner, Max von Kienlin; expedition truck in Persia; porters in Tarsching; Base Camp.

Felix Kuen and Reinhold Messner leaving Camp 1 on the Rupal Face.

Max von Kienlin and Hermann Kühn play chess as Reinhold Messner looks on.

Camp fire at Base Camp; Karl Herrligkoffer on the right.

A column of porters descends from Camp 2 in new snow.

The upper part of the Rupal Face. Beneath the summit to the left is the Merkl Couloir with the Merkl Icefield (Camp 4) below.

View from Camp 4 down into the Rupal Valley

Günther Messner clearing snow at the Ice Dome (Camp 3)

Camp 2 on the Rupal Face.

At the foot of the dangerous concave sweep of the Diamir Face, Reinhold Messner spent days’ searching for his brother Günther before heading down the valley.

Reinhold Messner searched for his brother in the glacial corrie at the foot of the Diamir Face (top left) before crawling down the dead Diamir Glacier (top right) to the upper Diamir Valley (bottom) and the first flowers and people.

The summit headwall of Nanga Parbat, viewed from the south.

It was in this climate of madness that, in 1970, a team set off to attempt the South Face of Nanga Parbat; the highest mountain face on Earth; the holy grail, too, for a young generation of mountaineers, for whom Herligkoffer was their only chance of making a successful ascent.

Tensions again arose between the expedition leadership and the summit team and again it came down to a solo summit bid, this time by Reinhold Messner. Messner’s brother Günther followed him of his own free will and on 27 June 1970 they reached the summit together. However, Günther succumbed to altitude sickness, and the two brothers were forced to descend by the Diamir Face, at the foot of which Günther perished.

Thus it was that that one man, many miles away from shelter of any kind, alone and abandoned, dragged his exhausted body down the Diamir Valley. Suffering schizophrenic delusions brought on by days without food or sleep, he talked to himself, the trees and the rocks, walking off his loneliness, his fear and desperation. Slipping gradually into the role of dispassionate spectator, he finally observed his own death. In a state of temporary insanity born of loss and desperation he miraculously returned to civilisation, a changed man.

Karl Maria Herrligkoffer, however, still obsessed with Merkl’s legacy, viewed Reinhold Messner’s descent in the same way as Buhl’s ascent all those years ago: as an act of treachery.

Chapter I

My Brother, His Death and My Madness

The South Face of Nanga Parbat, known as the Rupal Face.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!