1,90 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Lebooks Editora

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

One, None, and One Hundred Thousand by Luigi Pirandello is a profound exploration of identity, perception, and the fluidity of the self. In this novel, Pirandello presents a protagonist, Vitangelo Moscarda, who begins to question his sense of self after a casual remark about his appearance. This seemingly trivial event leads Moscarda to realize that he is perceived differently by every person he encounters, resulting in a crisis of identity. The novel delves into themes of existentialism, highlighting the disparity between how we see ourselves and how others perceive us. Moscarda's journey illustrates the fragmentation of identity, as he grapples with the notion that he is not a single, fixed individual but rather a multiplicity of selves shaped by the perspectives of others. The title itself — One, None, and One Hundred Thousand—reflects this idea, signifying the many versions of a person that exist in the minds of others, as well as the elusive nature of true self-knowledge.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 298

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Luigi Pirandello

ONE, NONE AND A HUNDRED-THOUSAND

Original Title:

“Uno, nessuno e centomila”

First Edition

Contents

INTRODUCTION

ONE, NONE AND A HUNDRED-THOUSAND

BOOK FIRST

BOOK SECOND

BOOK THIRD

BOOK FOURTH

BOOK FIFTH

BOOK SIXTH

BOOK SEVENTH

BOOK EIGHTH

INTRODUCTION

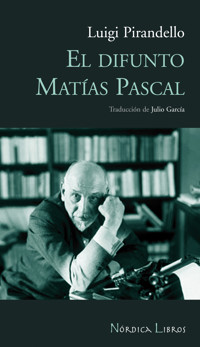

Luigi Pirandello

1867 - 1936

Luigi Pirandello was an Italian playwright, novelist, and short story writer, widely regarded as one of the most significant figures in 20th-century literature. Born in Agrigento, Sicily, Pirandello is best known for his exploration of themes such as identity, reality, and illusion, often blending the boundaries between fiction and reality in his works. His innovative approach to drama, particularly his use of meta-theater, earned him international acclaim, culminating in the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1934.

Early Life and Education

Luigi Pirandello was born into a prosperous family in Sicily. He initially studied at the University of Palermo before transferring to the University of Rome, and later, the University of Bonn, where he completed a doctoral thesis on the dialect of his native region. Pirandello’s education in both literature and linguistics greatly influenced his writing style, imbuing his works with a profound understanding of human psychology and the complexities of language.

Career and Contributions

Pirandello’s early career was marked by the publication of several novels and short stories, many of which were set in Sicily and reflected the social and cultural struggles of the region. However, it was in the world of theater that Pirandello left his most lasting legacy. His plays, such as Six Characters in Search of an Author (1921) and Henry IV (1922), broke new ground with their meta-theatrical structure, exploring the unstable nature of identity and the blurred lines between appearance and reality.

In Six Characters in Search of an Author, Pirandello presents a group of fictional characters who interrupt a rehearsal, claiming they are in search of an author to finish their story. This work is a powerful commentary on the fluidity of human identity and the complex relationship between life and art. Similarly, Henry IV delves into questions of madness and reality, telling the story of a man who believes himself to be the medieval German emperor Henry IV after suffering a mental breakdown.

Pirandello's concept of the "mask" plays a central role in his literature, where individuals often wear metaphorical masks to navigate social roles, leaving the true self hidden and unknowable. This theme resonates across much of his work, revealing the existential conflict between personal identity and societal expectations.

Impact and Legacy

Pirandello's contributions to modern drama were groundbreaking, particularly his challenge to traditional narrative forms. He is considered one of the fathers of modernist and absurdist theater, paving the way for later playwrights like Samuel Beckett and Eugène Ionesco. His exploration of the fragmented self and the uncertainty of reality influenced not only theater but also psychology and philosophy, contributing to existentialist thought.

His Nobel Prize win in 1934 solidified his place in the literary canon. Pirandello's plays and novels continue to be performed and studied globally, offering a timeless examination of the human condition, where truth is often elusive, and the self is never fully known.

Death and Legacy

Luigi Pirandello died in 1936 in Rome, shortly after completing one of his final works, The Mountain Giants, which remained unfinished. In accordance with his wishes, his funeral was a modest affair, reflecting the introspective nature of his life and work.

Today, Pirandello's legacy endures in his profound exploration of reality, identity, and illusion. His innovative contributions to theater have left an indelible mark on modern drama, and his works continue to provoke deep reflection on the nature of existence.

About the Work

One, None, and One Hundred Thousand by Luigi Pirandello is a profound exploration of identity, perception, and the fluidity of the self. In this novel, Pirandello presents a protagonist, Vitangelo Moscarda, who begins to question his sense of self after a casual remark about his appearance. This seemingly trivial event leads Moscarda to realize that he is perceived differently by every person he encounters, resulting in a crisis of identity.

The novel delves into themes of existentialism, highlighting the disparity between how we see ourselves and how others perceive us. Moscarda's journey illustrates the fragmentation of identity, as he grapples with the notion that he is not a single, fixed individual but rather a multiplicity of selves shaped by the perspectives of others. The title itself — One, None, and One Hundred Thousand—reflects this idea, signifying the many versions of a person that exist in the minds of others, as well as the elusive nature of true self-knowledge.

Pirandello critiques the human tendency to cling to rigid definitions of self, emphasizing the chaotic and ever-changing nature of existence. His work explores the tension between individual freedom and societal expectations, suggesting that the pursuit of a singular, stable identity is ultimately futile.

Since its publication, One, None, and Hundred Thousand has been recognized as a masterpiece of modernist literature, influencing existential and absurdist thinkers. Its exploration of identity, perception, and the fragmented self continues to resonate with readers, making it a timeless reflection on the complexities of human existence.

ONE,NONE AND A HUNDRED-THOUSAND

BOOK FIRST

I. My Wife and My Nose

"What are you doing?" my wife asked me, as she saw me lingering, contrary to my wont, in front of the mirror.

"Nothing," I told her. "I am just having a look here, in my nose, in this nostril. It hurts me a little, when I take hold of it."

My wife smiled.

"I thought," she said, "that you were looking to see which side it is hangs down the lower."

I whirled like a dog whose tail has been stepped on:

"Which side hangs down the lower? My nose? Mine?"

"Why, yes, dear," and my wife was serene, "take a good look; the right side is a little lower than the other."

I was twenty-eight years old; and up to now, I had always looked upon my nose as being, if not altogether handsome, at least a very respectable sort of nose, as might have been said of all the other parts of my person. So far as that was concerned, I had been ready to admit and maintain a point that is customarily admitted and maintained by all those who have not had the misfortune to bring a deformed body into the world, namely, that it is silly to indulge in any vanity over one's personal lineaments. And yet, the unforeseen, unexpected discovery of this particular defect angered me like an undeserved punishment. It may be that my wife saw through this anger of mine; for she quickly added that, if I was under the firm and comforting impression of being wholly without blemishes, it was one of which I might rid myself; since, just as my nose sagged to the right —

"Something else?"

Yes, there was something else! Something else! My eyebrows were like a pair of circumflex accents, ^ ^; my ears were badly put on, one of them standing out more than the other; and there were further shortcomings —

"What, more?"

Ah, yes, more: my hands, the little finger; and my legs (no! surely they were not crooked!) — the right one was bowed slightly more than the other, toward the knee — ever so slightly.

Following an attentive examination, I had to admit that all these defects existed. It was only then, when the feeling of astonishment that succeeded my anger had definitely changed to one of grief and humiliation — it was only then that my wife strove to console me, urging me not to take it so to heart, since with all my faults, when all was said, I was still a handsome fellow. I made the best of it, accepting as a generous concession what had been denied me as a right. I let out a most venomous "thanks," and, safe in the assurance that I had no cause for either grief or humiliation, proceeded to attribute not the slightest importance to these trifling defects; but I did confer a very great and extraordinary importance upon the fact that I had gone on living all these years without ever once having changed noses, keeping the same one all the time, and with the same eyebrows and the same ears, the same hands and the same legs — and to think that I had had to take a wife, to realize that they were not all that they should be.

"Huh! small wonder in that! Doesn't everybody know what wives are for? Made, precisely, for discovering a husband's faults."

True enough, mind you — I don't deny this about wives. But I may tell you that, in those days, I was prone to fall, at any word said to me, at the sight of a housefly1 buzzing about, into deeps of reflection and pondering that left me with a hollow feeling inside, and which rent my soul from top to bottom and tore it inside out like a molehill, without any of all this being visible on the outside.

"It is plain to be seen," you will tell me, "that you had plenty of time to squander."

Not exactly that, I would have you know. Some allowance is to be made for the state of mind I was in. But beyond that, I don't deny that my life was leisurely to the point of idleness. I was well-to-do, and a pair of faithful friends, Sebastiano Quantorzo and Stefano Firbo, had looked after my interests since my father's death. My father, by fair means or other, had not succeeded in doing anything with me, beyond seeing that I married at a very early age, possibly with the hope that I would at least provide a son who would be not at all like me; but the poor man had not been able to get even this out of me. It was not, understand, that I opposed any will of my own to taking the path upon which my father wished to embark me. I took them all. But taking them was all I did; I did not do any walking to speak of, but would come to a halt at every step, at every smallest stone I encountered, to hover about it, first at a distance and then closer up; and I wondered no little how others could go on past me, without taking any account whatever of that stone, which for me meanwhile had come to assume the proportions of an insurmountable mountain, as well as those of a world in which, without any further ado, I might have made myself at home.

I had remained halting like this at the first steps I had taken along so many paths, my mind full of worlds, or of little rocks, which amounts to the same thing. As a matter of fact, it did not seem to me that those who had passed me, and who had gone all the way, were substantially any the wiser than I. They had passed me, there was no doubt about that, prancing like colts; but at the end of the road, what they had found was a cart, their own cart; they had harnessed themselves to it with a vast deal of patience, and were now engaged in drawing it after them. But I drew no cart, and bore, accordingly, neither bridle nor blinders; I could certainly see farther than they; but go — where was there to go?

Coming back now to the discovery of those slight defects, I was immersed all of a sudden in the reflection that it meant — could it be possible? — that I did not so much as know my own body, the things which were most intimately a part of me: nose, ears, hands, legs. And turning to look at myself once more, I examined them again. It was from there that my sickness started, that sickness which would speedily have rendered me so wretched and despairing of body and of mind that I should certainly have died of it or gone mad, had I not found in my malady itself the remedy (I may say) which was to cure me of it.

II. And What About Your Own?

I at once imagined that everybody, now that my wife had made the discovery, must be aware of those same bodily defects, and that they must see nothing else in me.

"Is it my nose you are staring at?" I suddenly asked a friend, that very day, who had stopped to speak to me of some matter or other that meant a great deal to him.

"No," he said. "Why?"

I smiled nervously:

"The right side is a little lower, haven't you noticed?"

And I insisted upon his pausing to observe it attentively, as if that defect in my nose were an irreparable hitch that had occurred in the mechanism of the universe. My friend surveyed me at first in some astonishment; he surely suspected that my reason for thus, suddenly and without rhyme or reason, dragging in that remark about my nose, was that I did not deem the business of which he had been speaking to me worth my attention or a reply, for he gave a shrug of the shoulders and started to leave me, unceremoniously. I caught him by the arm.

"No, no," I said, "I am very much interested in your proposition. But you will have to excuse me for the moment."

"Is it your nose you're thinking of?"

"I never noticed before that it sagged to the right. My wife called my attention to it this morning."

"Really?" said my friend. His tone was questioning, and there was an incredulous and even derisive smile in his eyes.

I stood there gazing at him, as I had gazed at my wife that morning, with a mixture, that is to say, of humiliation, of anger and of astonishment. So he, too, had noticed it, had he? And how many others! How many? Yet I had been unaware of it, and, being unaware, had gone on believing that I was to everybody a Moscarda with a straight nose, whereas the truth was, everyone saw me as a Moscarda with a crooked nose. And how many times, quite unsuspectingly, had I chanced to speak of Tizio or Cajo's defective nose, and how many times must I have caused a laugh, as those who heard me thought: "But just give a look at that poor chap, will you, talking about other people's faulty noses!"

It is true, I might have consoled myself with the reflection that, in the long run, my case was obviously common enough, all of which only goes to prove once again a well-known fact, namely, that we are ready enough to note the faults of others, while all the time unconscious of our own.

The first germs of the malady had, however, begun to take root in my mind; and this reflection was unable to bring me any consolation. The thought, rather, remained firmly planted, that I was not for others what up to then I had inwardly pictured myself as being.

For the moment, I was thinking only of my body; and as my friend still stood there in front of me, with that derisive and incredulous air, I asked him, by way of retaliation, if he, for his part, knew that he had a dimple in his chin, which divided it into two not wholly equal parts, one of which stood out more than the other.

"I? What are you talking about! I have a dimple, I know, but it's not like what you say."

"Let's go into that barber shop over there," I suggested to him on the spur of the moment, "and you will see."

When my friend, having gone into the barber's, had satisfied himself to his own astonishment that what I had told him was true, he did his best not to display any annoyance, but observed that, when all was said, it was a trifling matter.

No doubt, he was right: it was a trifling matter; but following him at a distance, I saw him stop first at one shop window and then at another, further down the street; and then, yet further down, he came to a stop for a third time, before a shop-front mirror, to have a look at his chin; and I am quite sure that, the moment he reached his house, he must have run to the clothes press in order more conveniently to become acquainted with his new and blemished self. Nor have I the slightest doubt that, by way of avenging himself in his turn, or by way of carrying out a jest which he thought deserved to be passed along, he proceeded to treat some other friend as I had treated him, and that, after having inquired if the friend had noticed that blemish in his chin, he had gone on to discover some defect or other in his friend's forehead or mouth; while his friend, in turn — Ah, yes! ah, yes! — I could swear that, for days in a row, in the worthy city of Richieri, I saw (unless it was nothing more than my own imagination) a very considerable number of my fellow citizens going from one shop window to another and coming to a stop before each to observe their own reflections, one to study a zygoma, another the corner of his eye, a third to examine the lobe of an ear, and a fourth to investigate his nostril. At the end of a week, moreover, a certain acquaintance accosted me; he appeared to be perplexed, and asked me if it was true that, every time he went to speak, he inadvertently contracted his left eyebrow.

"Yes, old man," I hastened to assure him. "Look at me, will you? My nose sags to the right; but I know it without your telling me. And my circumflex eyebrows! And my ears — look here — one of them stands out more than the other. And my hands — dumpy, aren't they? And the crooked joint on this little finger. And my legs — here, look at this one, this one here — does it look to you the same as the other one? It doesn't, does it? But I know it without your telling me. See you later."

I left him standing there and was on my way. I had taken but a few steps, when I heard a call:

"Ps-t!"

With the utmost serenity, the fellow buttonholed me and drew me to him.

"Excuse me," he inquired, "but your mother did not bear any other sons after you, did she?"

"No," I replied, "neither before nor after. I am an only son. Why?"

"Because," he said, "if your mother had given birth another time, it would surely have been a male."

"Yes? How do you know?"

"Listen, and I will tell you. The women of the people have a saying that, when the hair on the back of the neck ends in a little bobtail like the one you have, the next born will be a boy."

I put a hand to the back of my neck.

"Ah," I said, coldly and with the beginning of a sneer, "so I have a — what do you call it? — "

"A bobtail, old man; that's what we call it in Richieri."

"Oh, that's nothing!" I exclaimed. "I can have it cut off."

He contradicted me with his finger:

"It's a sign that will stay with you, old boy, even if you have it shaved off."

And this time, it was he who left me in the lurch.

III. A Fine Way of Being Alone!

From that day on, I longed most ardently to be alone, if only for an hour. It was really more than a longing; it was a need, a sharp and pressing, a restless need, which was aggravated to the point of fury by the presence or proximity of my wife.

"Did you hear what Michelina said yesterday, Gengè?2 Quantorzo has something urgent to talk to you about."

"Look and see, Gengè, if my legs show with my dress this way."

"Gengè, the clock has stopped."

"Aren't you taking the dog out any more, Gengè? She'll ruin the carpets, then, and you'll scold her. You really ought to, you know, poor little beast — I mean — I'm not saying that — She hasn't been out since yesterday."

"Aren't you afraid, Gengè, that Anna Rosa may be ill? We haven't seen anything of her for three days now, and the last time she was here, she had a sore throat."

"Signor Firbo was here, Gengè. He said he would be back later. Couldn't you arrange to see him somewhere else? Good Lord, what a bore!"

Or else, I heard her singing:

E se mi dici di no,

caro il mio bene, doman non verrò;

doman non verrò...

doman non verrò...3

But why didn't you shut yourself in your room and blindfold your eyes if necessary?

My friends, that shows you do not understand the way in which I wanted to be alone.

The only place where I could shut myself in was my study; and even here, T did not dare put the bolt on the door, from fear of arousing unpleasant suspicions in my wife, who was, I shall not say an unpleasant woman, but a highly suspicious one. And supposing that, opening the door suddenly, she had discovered me?

No, it would not do. And anyway, it would have been useless. There were no mirrors in my study.

I had need of a mirror. Furthermore, the mere thought of my wife's being in the house was sufficient to keep me in the presence of myself, which was exactly what I did not want.

What does being alone mean to you?

Keeping your own company, without any stranger about.

Ah, well, I can assure you, it's a fine way, that, of being alone. A charming little window opens for you in memory, at which, smilingly, between a vase of pinks and one of jasmine, you catch sight of Titti, knitting away at a red woolen muffler, good Lord, like the one which that impossible old Signor Giacomino wears about his neck, for whom you have not yet written that letter of introduction to the president of the Association of Charities, your good friend but another terrible bore, especially when he starts talking about the fraudulent conduct of his private secretary, the one who yesterday — no, when was it? — the day before yesterday, the day it rained and the public square looked like a lake with all the raindrops glistening in a merry sprinkling of sunlight, and in the corsa, Lord, what a medley, the basin, the newspaper-kiosk, the tramcar threading its way through the junction and making so horrible a noise at the turn, that dog running away; but enough of this; you made your way into a billiard parlor where the secretary to the president of the Association of Charities was; and what repressed laughter there was under the big bristling mustaches, over your discomfiture, when you started playing with friend Carlino, or Quintadecima.

And then? What happened then, when you came out of the billiard parlor? Under a languishing lamp, in the moist and deserted street, a poor melancholy drunkard was endeavoring to sing an old Neapolitan ditty, one which, all these years ago, you used to hear almost every night, in that mountain village among the chestnuts, where you had gone for an outing in order to be near that darling Mimi of yours, who afterwards married the old Commendator Della Venera and died a year later. Dear, dear Mimi! There she is, see her? at another tiny window opening for you in memory —

Yes, yes, good people, I assure you, that is a fine way of being alone, that is!

IV. The Way in Which I Wanted to Be Alone

I wanted to be alone in an altogether unusual way, a new way. Quite the contrary of what you think: that is to say, without myself and, to be precise, with a stranger at hand.

Does this impress you as being a first sign of madness?

May not this be due to a lack of reflection on your part?

It may be that madness was in me already, I am not saying that it was not; but I beg you to believe that the only way of being truly alone is the one of which I am telling you.

Solitude is never where you are; it is always where you are not, and is only possible with a stranger present; whatever the place or whoever the person, it must be one that is wholly ignorant concerning you, and concerning which or whom you are equally ignorant, so that will and sensation remain suspended and confused in an anxious uncertainty, while with the ceasing of all affirmation on your part, your own inner consciousness ceases at the same time. True solitude is to be found in a place that lives a life of its own, but which for you holds no familiar footprint, speaks in no known voice, and where accordingly the stranger is yourself.

This was the way in which I wanted to be alone. Without myself. I mean to say, without that self which I already knew, or which I thought I knew. Alone with a certain stranger, from whom I darkly felt that I should be able never more to part, and who was myself: the stranger inseparable from me. There was, then, one only that interested me! And already, this one, or the need I felt of being alone with him, of confronting him in order to know him better and hold a little converse with him, was working me up to a pitch of half shivering alarm.

If I was not for others what up to then I had believed myself to be to myself, what was I?

In the course of living, I had never thought of my nose, of its size, whether big or small, of the color of my eyes, or the narrowness or breadth of my forehead, and so forth. This was my nose, those were my eyes, this was my forehead; things inseparable from me, of which, immersed in my own affairs, taken up with my own ideas, given over to my own feelings, I had had no time to think.

But I was thinking now:

"And others? Others are not in me at all. For others, who look from without, my ideas, my feelings have a nose. My nose. And they have a pair of eyes, my eyes, which I do not see but which they see. What relation is there between my ideas and my nose? For me, none whatever. I do not think with my nose, nor am I conscious of my nose when I think. But others? Others, who cannot see my ideas within me, but who see my nose without? For others, there is so intimate a relation between my ideas and my nose that if the former, let us say, were very serious while the latter was mirth provoking by reason of its shape, they would burst out laughing."

As I ran on like this, a fresh anxiety laid hold of me: the realization that I should not be able, while living, to depict myself to myself in the actions of my life, to see myself as others saw me, to set my body off in front of me and see it living like the body of another. When I took up my position in front of a mirror, something like a lull occurred inside me; all spontaneity vanished; every gesture impressed me as being fictitious or a repetition.

I could not see myself live.

I was to have a proof of this in the impression with which I was, so to speak, assailed a few days afterward, when, walking and talking with my friend, Stefano Firbo, I happened to catch an unexpected glimpse of myself in a mirror along the street, one that I had not noticed at first. This impression had not lasted more than a second, when that lull promptly occurred, spontaneity disappeared, and self-consciousness set in. I did not recognize myself at first. The impression was that of a stranger going down the street and engaged in conversation. I came to a halt. I must have been very pale.

"What's the matter?" Firbo asked me.

"It's nothing," I said. And to myself, seized by a strange fear that was at the same time a chill, I thought:

"Was it really my own, that image glimpsed in a flash? Am I really like that, from the outside, when — all the while living —

I do not think of myself? For others, then, I am that stranger whom I surprised in a mirror; I am he and not the I whom I know; I am that one there whom I myself at first, upon becoming aware of him, did not recognize. I am that stranger whom I am unable to see living except like that, in a thoughtless second. A stranger whom others alone can see and know, not I."

From that time on, I had one despairing obsession: to go in pursuit of that stranger who was in me and who kept fleeing me; whom I could not halt in front of a mirror, without his at once becoming the me that I knew; the one who lived for others and whom I could not know; whom others beheld living and not I. I wanted to see and know him, too, as others saw and knew him.

I still believed, I may repeat here, that the stranger in question was a single individual: one to all, even as I believed that I was a single individual to myself. But my atrocious drama speedily grew more complicated, with the discovery of the hundred-thousand Moscardas that I was, not only to others, but even to myself, all with the single name of Moscarda, a name that was ugly to the point of cruelty, all of them lodged within this poor body which was likewise one, one and none, alas, if I took up my position in front of a mirror and, standing motionless, looked it straight in the eyes, thereby abolishing in it all feeling and all will of its own.

It was as my drama grew thus more complicated that those fits of incredible madness came upon me.

V. In Pursuit of the Stranger

I shall speak now of those little games in the form of pantomime in which, in the sprightly infancy of my folly, I began to indulge in front of all the mirrors in the house, being careful to look to right and left to make sure that I was not observed by my wife, waiting eagerly until she went out to make a call or for some purchase or other, leaving me alone at last for some little time.

The thing that I strove to do was not, like a comedian, to study my movements, to compose my face for the expression of various emotions and mental impulses; on the contrary, what I wanted to do was to take myself by surprise, in my own natural actions, in those sudden alterations of countenance which accompany the mind's every movement; by way of capturing, for example, an expression of unforeseen astonishment (over every trifle, I would fling up my eyebrows to the roots of my hair and would open my eyes and mouth as widely as I could, stretching out my face as if it had been drawn by an internal wire); or a profound sorrow (and I would screw up my forehead, as I pictured the death of my wife, half-closing my eyelids, somberly, as if brooding over my grief); or a fierce rage (and I would gnash my teeth, imagining that someone had slapped my face, and would curl up my nose, stick out my lower jaw, and flash a lightning-look).

But, first of all, that astonishment, that sorrow, that rage was feigned; they could not have been real, for the reason that had they been so, I should not have been able to view them; they would at once have ceased, owing to the very fact that I was viewing them. In the second place, the fits of astonishment that might take possession of me were exceedingly diverse in character, and the accompanying expressions were similarly and endlessly variable according to the moment and the state of mind that I was in; and the same went for all my griefs and rages. And lastly, even granting that for one single and definite feeling of astonishment, for one single and definite grief, one single and definite fit of rage, I might really have been able to assume the appropriate expressions, those expressions would have been as I saw them and not as others would have seen them. My expression of rage, for instance, would not have been the same to one who feared it, to another disposed to excuse it, to a third inclined to smile at it, and so on.

Ah! what good sense I still had, to be able to grasp all this; and yet, I was unable to make use of it, by way of drawing from the obvious impracticality of my crazy purpose the natural deduction that the best thing to do would be to renounce the hopeless undertaking and be content with living for myself, without seeing myself, and without concerning myself with any thought of others.

The idea that others saw in me one that was not the I whom I knew, one whom they alone could know, as they looked at me from without, with eyes that were not my own, eyes that conferred upon me an aspect destined to remain always foreign to me, although it was one that was in me, one that was my own to them (a "mine," that is to say, that was not for me!) — a life into which, although it was my own, I had no power to penetrate — this idea gave me no rest. How could I endure this stranger within me? This stranger who was I myself to me? How go on not seeing him? Not knowing him? How remain condemned forever to bear him about with me, in me, in the sight of all others, and all the while outside my own?

VI. At Last!

"Do You know what, Gengè? Four days more have gone by. There cannot be any doubt about it, Anna Rosa must be ill. I'm going to see her."

"Dida, dear, what are you thinking of? What an idea! In this weather? Send Diego; send Nina to find out how she is. Do you want to run the risk of falling ill yourself? I won't have it; I absolutely won't have it."

When you absolutely will not have a thing, what does your wife do?

My wife, Dida, put on her bonnet. Then she handed me her cloak to hold for her. I could have leaped for joy. But Dida, in the mirror, caught sight of my smile:

"You're laughing, are you?"

"My dear, when I see how I am obeyed — "

And then, I begged her at least not to stay too long with her friend, if the latter really was suffering from a sore throat:

"A quarter of an hour, no more. Please."

In this manner, I made sure that she would not be home until nightfall. No sooner had she gone out than I spun about on my heel for joy, clapping my hands together.

"At last!"

VII. Draught of Air

I wanted first to compose myself, to wait until every trace of anxiety or of joy had disappeared from my countenance, until every impulse to thought or feeling had come to a halt inside me, in order that I might be able to take in front of the mirror a body that was, so to speak, strange to me, and as such, stand it up in front of me.

"Come," I said, "let's be on our way!"

I went with eyes shut and with my hands groping before me. When I had touched the side of the clothes press, I paused again to await, with eyes shut still, an inner calm and an indifference that should be as absolute as possible. But a cursed voice from within kept telling me that he was there, too, the stranger, there in front of me, in the mirror. Waiting like me, with eyes shut. He was there, and I did not see him. Nor did he see me, since, like me, he had his eyes closed. But what was he waiting for? To see me? No. He could be seen, but could not see. He was to me what I was to others; I could be seen but could not see myself. Yet if I opened my eyes, would I see him like another?