1,90 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Lebooks Editora

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

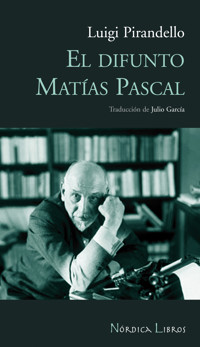

Luigi Pirandello was an Italian writer and playwright, author of enormously successful works such as "The Late Mattia Pascal" and "The Outcast." "The Late Mattia Pascal" tells the story of the titular character who, after successive misfortunes in life, culminating in an unwanted marriage, has the opportunity to start his life anew after winning a fortune in France and, at the same time, is declared dead in his hometown. Returning to Italy, he decides to live in Rome, where he begins a new life with a new identity. Disappointed with his existence and challenged to a duel, he fakes a second death, ultimately deciding to resume his former existence: an existence that no longer exists. "The Late Mattia Pascal" was one of the works that contributed most to the author's popularity, both within Italy and internationally. In 1934, Luigi Pirandello was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 470

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Luigi Pirandello

THE LATE MATIA PASCAL

Original Title:

“Il fu Mattia Pascal”

Contents

INTRODUCTION

THE LATE MATTIA

I - “My Name is Mattia Pascal”

II - “Go to It,” Says Don Eligio

III - A Mole Saps Our House

IV - Just as It Was

V - How I Was Ripened

VI - ... Click, Click, Click, Click ...

VII - I Change Cars

VIII - Adriano Meis

IX - Cloudy Weather

X - A Font and an Ash-tray

XI - Night ... and the River

XII - Papiano Gets My Eye

XIII - The Red Lantern

XIV - Max Turns a Trick

XV - I and My Shadow

XVI - Minerva’s Picture

XVII - Reincarnation

XVIII - The Late Mattia Pascal

INTRODUCTION

Luigi Pirandello

1867 – 1936

Novelist, short story writer, and playwright, Luigi Pirandello is one of Italy's greatest artists of his time. Awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1934 for his "brilliant and courageous renewal of drama and stage," he was throughout his life a prolific writer who, by renewing his own style, moved from the regional naturalism of his early works to the anti-traditionalism of the Grotesque Theater (defined as a combination of fantasy and reality), to self-reflection manifested in theater without theater, and finally to symbolism that shines through in his later works. Pessimism, madness, unreality, the impossibility of knowing the truth about people, sympathy for the oppressed, repudiation of conventions, and the fictitious nature of theatrical characters mark the essential foundations of Pirandello's thought.

According to critic Eric Bentley, one of the basic points of his thought — "the multiple personality" — hides a profound humanism, which takes refuge in isolation and loneliness. The Pirandellian man is not only isolated from friends but from himself. In a way, the Pirandellian man can be seen from an existentialist point of view. Life is absurd, almost always filled with nausea, fear, and anguish. Although man continues to struggle, hate, and defy, life is a continuous improvisation. In a certain way, his naturalistic psychology aligns with Freud's discoveries, as by dissecting his characters, he brings to light the unconscious personality that deeply complicates the rational apprehension of human behavior. A typical representative of the regional bourgeoisie that promoted Italian unification, Pirandello subjects the country's life to severe criticism.

The criticism included in the stories and novels, more ontological than social, is better developed in the theatrical plays, where he analyzes man as man, examining his individual motivations with bitter and realistic irony.

Born in the region of Agrigento (Sicily) on June 28, 1867, Luigi Pirandello was the son of a family of ancient Sicilians who were deeply involved in the struggle for the unity of Italy. His father, a prosperous sulfur merchant, intended for his son to study law, but from an early age, Pirandello showed a strong inclination for literature. At sixteen, he had already completed two poetry manuscripts. After a brief period studying Commerce at the University of Palermo, he transferred to the University of Rome, where he completed his degree in Philology. In 1891, he completed his doctorate in Bonn, Germany, by writing in German about the effects of sound on the formation of the dialect of his native region. After a short interval in Agrigento, where he unsuccessfully attempted commerce, Pirandello returned to Rome in 1893 and began associating with literary and artistic circles. He married Antonietta Portulano the following year, a family friend and wealthy heiress of a sulfur mine. With financial support from his parents and his wife's money, he devoted himself entirely to literature. However, in 1903, an incident at the sulfur mine caused Pirandello's wife to lose both her fortune and her sanity. From then on, Pirandello lived obscurely, spending bitter years in the company of his wife, writing, and teaching.

About the Work

His first success, "The Late Matia Pascal" (I Fu Mattia Pascal, 1904), and two volumes of essays, "Art and Science" and "Humor" (1908), were the result of his change of life. Previously, he had already published a translation of Goethe's novel "Elective Affinities," a narrative poem in verse, four volumes of short stories, which would later be incorporated into others in a two-volume collection (Novels for a Year), and a one-act comedy, "The Vice." After that, until the beginning of the First World War, he mainly wrote short stories and novels.

The first years of the war were very difficult for him. His two sons were made prisoners of war, and his wife's mental problems worsened. The production of his first three-act play, "If Not So, So Much the Better," later titled "The Reason of Others" (1921), marked his first failure in Rome, while the following year, "Six Characters in Search of an Author" (1921), was extraordinarily successful in Milan. In a short period, Pirandello wrote and saw sixteen plays staged, four of which were in Sicilian dialect. The success of the performances of his plays in Paris and New York marked a new phase in Pirandello's life. Frequent and intense contact with the theatrical world, both in Italy and abroad, encouraged him to attempt production and direction. In 1924, he founded his own company, inaugurating the Rome Art Theater the following year, which received financial support from the government. The Nobel Prize in 1934, two years before his death in Rome on December 1, 1936, was the natural culmination of a brilliant and innovative career.

Of the seven novels written by Pirandello, "The Outcast" (L'Esclusa, 1901) is noteworthy for the unconventional treatment it gives to the theme of adultery and, historically, for the subtly corrosive way in which it accepts the norms of Naturalism. He sought his own path for the naturalistic taste of the time. Marta, the heroine of the novel, is unjustly accused of adultery by her husband. He had found a platonic love letter signed by the local intellectual, Armand d'Alvignani. Rejected by her family, Marta moves to Palermo, where she finds a job as a teacher. More secure and independent, she is ready for love and becomes an easy prey for Armand. Convinced of Marta's innocence, her husband seeks her again, but it is too late. Although the novel is narrated in a cold and restrained style, as is typical of Naturalism, its ability to "mix" situations and the life of the heroine foreshadow, by its ambiguous aspect, a whole gallery of Pirandellian characters.

His initial theme was Sicily. The tragedies of the ancient island are narrated in a naturalistic manner, presenting traces of Verga's verism. His first success, the novella "The Late Mattia Pascal," psychologically depicts the conflicts of the central character, whose attempt to return to Sicily conceals the desire to start all over again. Here, Pirandello expresses his doubts about the identity of the human gender for the first time, a theme that would reappear in almost all of his later works.

The psychological problem of Mattia Pascal would be resolved sociologically in "The Old and the Young" (I Vecchi e i Giovani). Perhaps his best-realized novel, this work presents a bleak picture of 1890s Sicily, feudal and decadent. Other significant novels by Pirandello from this period are fragmented kaleidoscopic narratives told in the first person. "The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio" (1915), with its plotless plot scheme, already foreshadows his future dramatic plays. Due to its attack against "the machine that mechanizes life" — embodied in the movement of a cinema camera operated by the protagonist — and the way it deals with alienation, this book has not lost its relevance to this day. "One, None, and a Hundred Thousand" (1915), however, with its short and continuous chapters, with colloquial and humorous titles, is the structural counterpart of the protagonist's gradual discovery of his multiple personality and his final rejection of all forms of social repression and authoritarianism.

However, it is in Pirandello's short stories that the most suggestive texts in the Italian language since Boccaccio appear. Although neglected by some critics, they are considered by others to be superior to his dramatic works. The oldest of them, "Headgear," written in 1884, is a Sicilian composition in the manner of Giovanni Verga and is part of the author's regionalist phase, whose stories are characterized by popular heroes, tragicomic types, entangled in the most embarrassing situations. Other well-known short stories by Pirandello are those that would later be adapted as plays or had been previously planned for the stage, such as "The Jar" and "The Patent." In them, we find the figure of the narrator, prefiguring the typical narrative of Pirandellism. There is also a group of urban tales, such as "The Cathar Heresy," in which a professor is so obsessed with his esoteric research that he forgets to take care of his class students; or "The Wheelbarrow," in which a calm lawyer guards himself against madness by allowing himself a well-dosed act of irresponsibility every day. Finally, there are the vigorous and unsettling tales he wrote at the end of his life, in which action and violence occur more at the psychological level. In "The Destruction of the Man," a man driven mad by poverty kills his pregnant wife; in "Breath," whose protagonist realizes he has the power of life and death over other men; or in "Cinci," in which a boy kills a friend and simply forgets what he did.

However, it is in the theater that Pirandello would gain fame and fortune. His earliest theatrical works reflect different trends in contemporary theater. "The Duty of the Doctor" (1912) shows the conflicts of the bourgeoisie during the late 19th century; "Lumie di Sicilia" and "The Jar" belong to regional theater; "Airuscita" is a profane mystery; while "Liolà" combines Sicilian motifs with frequent themes in the Pirandellian universe: the triumph of irrationalism, the destruction of the self-elaborated mask of the individual, and the conflict between appearance and reality.

The first fundamentally important play in Pirandello's work would be "Right You Are (If You Think So)" (Cosi è), a parable that uses the provincial bureaucratic milieu to demonstrate the relativity of truth and defend the right of men to each have their "ghost" — creating for themselves a perfect illusion, in which they live in perfect harmony. In "Everything for the Best" (1920), the author maintains the tendency to dissociate the realistic foundations — reflected in the way the elements of the plot are narrated — and the particular sense of life that gives his stories a universal value.

"Enrico IV" (1922) is undoubtedly his greatest theatrical creation. Here, alienation reaches the dimensions of madness: initially real, later feigned. This, for him, is the only possible solution to protect his "specter" from the world of corruption, selfishness, and vice that weighs upon him. In this work, the pressure of life, one of Pirandello's strongest characteristics, is depicted with all its destructive impact.

In the theater-without-theater trilogy — "Six Characters in Search of an Author," "Each in His Own Way," and "Tonight We Improvise" — the focus shifts from the protagonist's anguish to the character's anguish in the search for being, and shows to what extent this reverberates in the process of creating art. At the same time, it ostentatiously relates the interaction between character, actor, and spectators in bringing the illusion of life to the stage — in reality, they should be seen only as an amusing, albeit brilliant, theatrical experience. Within this framework, we can observe that, for Pirandello, theater was the only way to express his concept of art.

A second trilogy — "The New Colony" (1928), "Lazzaro" (1929), and "The Mountain Giant" (1939) — described by Pirandello himself as "The Myths," marks the final stage of his career as an author. In it, the frame of reference is no longer the individual, whose experience is universalized, but society itself. "The Mountain Giant," unfinished due to Pirandello's death, is among his masterpieces. In the figure of the magician Cotrone, who lives with his refugees from the real world in an abandoned city projected into a world of fantasy, Pirandello creates a final projection of himself as a modest artist who perceives around him an abundant life that never ends.

THE LATE MATTIA

I - “My Name is Mattia Pascal”

One of the few things, in fact about the only thing I was sure of was my name: Mattia Pascal. Of this I took full advantage also. Whenever one of my friends or acquaintances so far lost his head as to come and ask me for a bit of advice on some matter of importance, I would shrug my shoulders, squint my eyes and answer:

“My name is Mattia Pascal!”

“That’s very enlightening, old man! I knew that much already!”

“And you don’t feel lucky to know that much?” There was no reason why he should that I could see. But at the time I had not realized what it meant not to be sure of even that much — not to be able to answer on occasion, as I had formerly answered:

“My name is Mattia Pascal!”

Some people surely will sympathize with me (sympathy comes cheap) when they try to imagine the immense anguish a poor man must feel on suddenly discovering ... well, yes ... just a blank; that he knows neither who his father was, nor who his mother was, nor how, nor when, nor where, he was horn — if ever he was born at all... . Just as others will be ready to criticize (criticism comes cheaper still) the immorality and viciousness of a society where an innocent child can be treated that way.

Very well! Thanks for the sympathy and the holy horror! But it is my duty to give notice in advance that it’s not quite that way. Indeed, if need should arise, I could give my family tree with the origin and descent of all my house. I could prove that I know my father and my mother and their fathers and mothers unto several generations and the doings, through the years, of all those forebears of mine (doings not always to their untarnished credit, I must confess).

Well then?

Well then! It’s this way. My case, not the ordinary one, by any means, is so far out of the ordinary in fact, that I have decided to recount it.

For some two years I held a position — mouse-catcher and custodian in one — in the so-called Boccamazza library. Away back in the year 1803, a certain Monsignor Boccamazza, on departing from this life, left his books as a legacy to our village. It was always clear to me that this" venerable man of the cloth knew nothing whatever about the dispositions of his fellow-citizens. I suppose he hoped that his benefaction, as time and opportunity favored, would kindle a passion for study in their souls. So far not a spark has ever glowed therein, as I may state with some authority and with the idea of paying a compliment, rather than not, to my fellow-townsmen. Indeed, our village so little appreciated the gift of the reverend Boccamazza that it has, to this day, refused money even for putting his head, neck and shoulders into marble; and for years and years the books he left were never removed from the damp and musty store house where they had been piled after his funeral. Eventually, however, they were transported (and imagine in what condition!) to the unused Church of Santa Maria Liberate, a building which, for some reason or other, had been secularized. There the town government entrusted them to any one of its favorites who was looking for a sinecure and who, for two lire a day, was willing to care for them (or to neglect them if he chose) and to stand the noxious odor of all that mildewed paper.

This plum, in the course of human events, fell to me and I must add that the first day of my incumbency gave me such a distaste for books and manuscripts in general (some of those under my charge were very precious, I am told) that I should never, never, of my own accord, have thought of increasing the number of them in the world by one. But, as I said, my case is a very strange one; and I now agree that it may prove of interest to some chance reader, who, in fulfillment of Monsignor Boccamazza’s pious hope, shall someday wander into the library and stumble upon this manuscript of mine. For I am leaving it to the foundation, with the understanding that no one shall open it till fifty years after my third, last and final death.

There you have it, exactly! So far I have died twice (and the Lord knows the extent of my regret, I can assure you) : the first time I died by mistake; and the second time I died ... but that’s my story, as you will see.

II - “Go to It,” Says Don Eligio

The idea or rather the suggestion, that I write such a book came to me from my reverend friend, Don Eligio Pellegrinotto, the present custodian of the Bocca-mazza gift; and to his care (or neglect) I shall entrust the script when it is finished (if ever I reach the end).

I am writing it here in this little deconsecrated church, under the pale light shed from the windows of the cupola, here in the librarian’s “office” (one of the old shrines in the apse, fenced off by a wooden railing), where Don Eligio sits, panting at the task he has heroically assumed of bringing a little order into this chaos of literature.

I doubt whether he gets very far with it.

Beyond a cursory glance over the ensemble of the bindings, no one before his time ever took the trouble to find out just what kind of books the old Monsignore’s legacy contained (we took it for granted that they bore mostly on religion). Well, Don Eligio has discovered (“Just my luck!” says he) that their subject-matter is extremely varied on the contrary; and since they were gathered up haphazard, just as they lay in the store house and set on the shelves wherever they would fit, the confusion they are in is, to say the least, appalling. Odd marriages have resulted between some of these old volumes. Don Eligio tells me, that it took him a whole forenoon to divorce one pair of books that had embraced each other by their bindings: “The Art of Courting Fair Ladies,” by Anton Muzio Porro (Perugia, 1571); and (Mantua, 1625), “The Life and Death of the Beatified Faustino Materucci ”! (One section of Muzio’s treatise is devoted to the debaucheries of the Benedictine order to which the holy Faustino belonged!)

Climbing up and down a ladder he borrowed from the village lamp-lighter, Don Eligio has unearthed many interesting and curious tomes on those dust-laden shelves. Every time he finds one such, he takes careful aim from the rung where he is standing and drops it, broadside down, on the big table in the center of the nave. The old church booms the echo from wall to wall. A cloud of dust fills the room. Here and there a spider can be seen scampering to safety on the table top. I saunter along from my writing desk, straddle the railing and approach the table. I pick up the book, use it to crush the vermin that have been shaken out, open it at random and glance it through.

Little by little I have acquired a liking for such browsing. Besides, Don Eligio tells me I should model my style on some of the mouldy texts he is exhuming here — give it a “classic flavor” as he says. I shrug my shoulders and remark that such things are beyond me. Then my eye falls on something curious and I read on.

When at last, grimy with dust and sweat, Don Eligio comes down from his ladder, I join him for a breath of clean air in the garden which he has somehow coaxed into luxuriance on a patch of gravel in the corner of apse and nave.

I sit down on a projection of the underpinning and rest my chin on the handle of my cane. Don Eligio is softening the ground about a head of lettuce.

“Dear me, dear me,” say I. “These are not the times to be writing books, Don Eligio, even fool books like mine. Of literature I must begin to say what I have said of everything else: ‘Curses on Copernicus!’ ”

“ Oh, wait now, “ exclaims Don Eligio, the blood rushing to his face as he straightens up from his cramped position. (It is hot at noon time and he has put on a broad-brimmed straw, for a bit of artificial shade.) “What has Copernicus got to do with it?”

“More than you realize, perhaps; for, in the days before the earth began to go round the sun. ...”

“ There you go again! It always went round the sun, man alive. ...”

“Not at all, not at all! No one knew it did; so, to all intents and purposes, it might as well have been sitting still. Plenty of people don’t admit even now that the earth goes round the sun. I mentioned the point to an old peasant the other day and do you know what he said to me? He said: ‘That’s a good excuse when someone swears you’re drunk!’ Even you, a good priest, dare not doubt that in Joshua’s time the sun did the moving. But that’s neither here nor there. I was saying that in days when the earth stood still and Man, dressed as Greek or Roman, had a reason for thinking himself about the most important thing in all creation, there was some justification for a fellow’s putting his own paltry story into writing.”

“The fact remains,” says Don Eligio, “that more trashy books have been written since the earth, as you insist, began going round the sun, than there were before that time. “

“I agree, ” say I. “ ‘ At half past eight, to the minute, the count got out of bed and entered his bathroom... . “The millionaire’s wife was wearing a low-necked gown with frills... .” They were sitting opposite each other at a breakfast table in the Ritz... ‘Lucretia was sewing at the window in the front room... .’ So they write nowadays. Trash, I grant you! But that’s not the question either. Are we or are we not, stuck here on a sort of top which some God is spinning for his amusement — a sunbeam maybe for a string; or, if you wish, on a mudball that’s gone crazy and whirls round and round in space, without knowing or caring why it whirls — just for the fun of the thing? At one point in the turning we feel a little warmer; at the next a little cooler; but after fifty or sixty rounds we die, with the satisfaction of having made fools of ourselves at least once every turn. Copernicus, I tell you, Don Eligio, Copernicus has ruined mankind beyond repair. Since his day we have all come gradually to realize how unutterably insignificant we are in the whole scheme of things — less than nothing at all, despite the pride we take in our science and the inventiveness of the human mind. Well, why get excited over our little individual trials and troubles, if a catastrophe involving thousands of us is as important, relatively, as the destruction of an ant-hill?”

Don Eligio observes, however, that no matter how hard we try to disparage or destroy the many illusions Nature has planted in us for our good, we never quite succeed. Fortunately man’s attention is very easily diverted from his low estate.

And he is right. I have noticed that in our village, on certain nights marked in the calendar, the streetlamps are not lighted; and on such occasions, if the weather happens to be cloudy, we are left in the dark. — Proof, I take it, that even in this day and age, we fancy that the moon is put there to give us light by night, just as the sun is put there to give us light by day (with the stars thrown in for decorative purposes). And we are only too glad to forget what ridiculously small mites we are, provided now and then we can enjoy a little flattery of and from each other. Men are capable of fighting over such trifles as land or money, experiencing the greatest joy and the greatest sorrow over things, which, were we really awake to our nothingness, would surely be deemed the most miserable trivialities.

To come to the point: Don Eligio seems to me so nearly right, that I have decided to avail myself of this faculty I share with other men for thinking myself worth talking about; and, in view of the strangeness of my experience, as I said, I am going to write it down. I shall be brief, on the whole, sticking closely to essentials; and I shall be frank. Many of the things I shall narrate will not help my reputation much. But I find myself in a quite exceptional position: as a person beyond this life. There is no reason, therefore, for concealing or mitigating anything.

So I proceed.

III - A Mole Saps Our House

I was a bit hasty in stating, a moment ago, that I knew my father. I can hardly claim as much. He died when I was four years old. He went on a trip to Corsica in the coaster of which he was captain and owner and never came back — a matter of typhus, I believe, which carried him off in three days at the untimely age of thirty-eight. Nevertheless he left his family well provided for — his wife, that is and two boys: Mattia (I that was in my first life) and Koberto, my elder by a couple of years.

The old people of our village enjoy telling a story to the effect that my father's wealth had a rather dubious origin (though I don't see why they continue to hold that up against him, since the property has long since passed from our hands). As they will have it, he got his money at a game of cards with the captain of an English tramp-steamer visiting Marseilles. The Englishman had taken on a cargo at some port in Sicily, a load of sulphur, it is specified, consigned to a merchant in Liverpool. (They know all the details, you see: Liverpool! Give them time to think and they'll tell you the name of the merchant and the street he lived on!) After losing to my father the large amount of cash he had on hand, than captain staked the sulphur — and again lost. The steamer arrived in Liverpool still further lightened by the weight of its master, who had jumped overboard at sea in despair. (Had it not been so well ballasted with the lies of my father’s de-famers, I dare say the ship would never have reached port at all!).

Our fortune was mostly in landed property. An adventurer of a roving disposition, my father was utterly unable to tie himself down to a business in one place. With his boat we went around from harbor to harbor buying here and selling there, dealing in goods of every sort. But to avoid the temptation of too hazardous speculations, he always invested his profits in fields and houses about our native town; intending, I suppose, to settle down there in his old age and enjoy, with his wife and children about him, the fruits of his imagination and hard work.

He bought — oh, he bought a place called Le Due Riviere — ‘‘Shoreacres,” as it were, for its olives and its mulberry trees; he bought a farm we called “The Coops,” with a pond on it, which ran a mill; he bought the whole hillside of “The Spur” — the best vineyard in our district; he bought the San Rocchino estate, where he built a delightful summer-house; in town he bought the mansion where we lived, two tenement houses and the building that has now been fixed over for the armory. .

His sudden death was the ruin of us. Utterly ignorant of business matters, my mother was obliged to entrust our fortune to someone. She chose as her steward a man who had been enriched by my father and who, as anyone would have thought, would be loyal out of sheer gratitude, if for nothing else; all the more since a high salary for his services would make honesty a good policy also. A saintly soul, my mother was! Naturally timid and retiring, as trustful as a child, she knew nothing at all about this world and the people who live in it. After my father’s death her health was never good; but she did not complain of her troubles to other people; and I doubt whether she lamented them much in her secret heart. She seemed to take them as a natural consequence of her great sorrow. The shock of that should have killed her — so she reasoned. Ought she not be thankful therefore to the good Lord who had vouchsafed her a few years more of life — be it indeed in pain and suffering — to devote to her children?

For us she had an almost morbid tenderness, full of worries and fancied terrors. She would scarcely let us out of her sight, for fear of losing us. Let her look up from her work to find one of us absent and the servants would be sent calling through the great mansion where we lived (the monument to my father’s ambition) to bring us back to her side.

Merging her whole existence in that of her husband, she felt lost in the world when he was gone. She never left- the house except' on Sundays — and then only to attend early mass in a church nearby, in company with two maids of long service with us whom she treated as members of the family. Indeed, to simplify her life still further, she lived in three rooms of our big house, abandoning the others to the haphazard care of the maids and to the pranks of us two boys.

I can still feel the impressiveness of those mysterious halls and chambers, all pretentiously furnished with massive antiques. The faded tapestries and upholstering gave off that peculiar odor of mustiness which is the breath, as it were, of ages that have died. More than once, I remember, I would look around, in strange consternation, upon those weirdly silent objects which had been sitting there for years and years motionless and unused!

Among my mother’s more frequent visitors was an aunt of mine on my father’s side — Scolastica by name, a bilious, irritable old maid, tall, dark-skinned, stern of bearing and with eyes like a ferret. Scolastica never stayed long at any one time. Invariably her visits ended in a quarrel which she would settle by stalking out of the house, without saying goodbye to anyone and slamming the doors behind her. I was terribly afraid of this redoubtable woman. I would sit in my chair without daring to stir, gazing at her with wide-opened eyes; especially when she would fly into a temper, turn furiously upon my mother and stamping angrily on the floor, exclaim:

“Do you hear that? Hollow, hollow, underneath! Ah, that mole! That mole! “

“That mole,” was Battista Malagna, the man in charge of our property, who, according to Scolastica, was boring the ground away beneath our feet. My aunt, as I learned years later, wanted mother to marry again at all costs. Ordinarily, the relatives of a dead husband do not give advice like this. But Scolastica had a severe and spiteful sense of the fitness of things. Her desire to thwart a thief, rather than any real affection for us, moved her to protest against Malagna’s robbing us with impunity. Since mother was blind to faults in anybody, Scolastica saw no possible remedy except bringing a new man into the house. And she had even picked her man — a poor devil, though a rich one, named Gerolamo Pomino.

Pomino was a widower with one boy. (The hoy, also a Gerolamo, is still living; in fact he is a friend, — I can hardly say a relative — of mine, as my story will show in due season. In those days Gerolamino or “Mino” as we called him, would come to our house along with his father, to be the torment of brother Berto and me.)

Years before, Gerolamo Pomino the elder had long aspired to the hand of my aunt Scolastica; but she had spumed him as, for that matter, she had spurned every other offer in marriage. It was not so much her lack of an impulse to love. As she put it, the faintest suspicion on her part that a husband might betray her even in his thoughts would drive her to murder, yes, to murder downright! And who ever heard of a faithful husband? All males were hypocrites, deceivers, scalawags!

“Even Pomino ?”

“Well, Pomino, no!”

One exception that proved the rule! But she had found that out too late. Carefully watching all the men who had proposed to her and then married someone else, she had found them, in every case, playing tricks on their wives — discoveries that afforded her a certain ferocious satisfaction. But Pomino had always been “straight.” In his case, the woman, rather, had been to blame.

“So why don’t you marry him, now, Cymanthia? Oh dear me! Just because he’s a widower? Just because there has been a woman in his life and he may give her a thought now and then that might otherwise have been for yon? That’s splitting things pretty fine! Besides, just look at him. You can see a mile away that he’s in love; and there’s no secret about who it is he wants, poor man!”

As though mother would ever have dreamed of a second marriage! A sacrilege that would have seemed in her eyes! I imagine that mother doubted, besides, whether Scolastica really meant everything she said; so when my aunt would start one of her long orations on the virtues of Pomino, mother would just laugh in her peculiar way. The widower was often present at such arguments. And I can remember him hitching about uncomfortably on his chair as Scolastica would overwhelm him in words of extravagant praise and trying to relieve his torture by the most wicked of his oaths: “ The dear Lord save us!” (Pomino was a dapper little old man with soft blue eyes. Berto and I thought there was just a suggestion of rouge on his cheeks. Certainly he was proud of keeping his hair so late in life; and he took the greatest pains in parting and brushing it. As he talked, he was continually smoothing it with his two hands.)

I don’t know how things would have turned out, had mother — not for her own sake, surely but as a safeguard for the future of her children — taken Aunt Scolastica’s advice and married Pomino. Surely nothing could have been worse than continuing with our affairs in the clutches of Malagna, “the mole.” By the time Berto and I were in long trousers, most of our inheritance had dwindled away; though something was still left — enough to keep us, if not in luxury, at least free from actual need. But we were careless youngsters, with not one serious thought in our heads. Instead of coming to the rescue of the remnants of our fortune, we persisted in the kind of life to which our mother had accustomed us as boys.

Never, for example, were we sent to school. We had a private tutor come to the house, a man called “Pin-zone, “ from the little pointed beard he wore. (His real name was Del Cinque,* but everybody called him “Pin-zone, “ and I believe he grew so used to it that he ended by signing his name that way himself.) He was an absurdly tall and an absurdly lean fellow; and there is no telling how much taller he might have grown, had his head and neck not toppled forward from his shoulders in a stoop that became a real deformity. Another feature was an enormous Adam’s apple that went up and down as he swallowed. Pinzone was always biting at his lips as though chastising a sarcastic little smile peculiar to him; a smile which, banished from his lips, managed to escape through two sharp eyes that ever showed a glittering mocking twinkle.

That pair of eyes must have seen many things in our house to which mother and we two boys were blind. But Pinzone said nothing, perhaps because it was not his place to interfere; or, as I believe more probable, because he took a vindictive pleasure in the thought of us boys being as poor as he someday. For Berto and I ragged him unmercifully. As a rule he would let us do anything we chose; but then again, as though to ease his conscience, he would tell on us at times when we least expected.

Once, I remember, mother had asked him to take us to Church. It was Easter time and we were to prepare for Confession. Thence we were to call at Malagna’s house and express our sympathy to Signora Malagna who was ill. Not a very exciting program for two boys our age and in such fine weather! We were hardly out of mother’s hearing when we proposed a revision of the day’s work. We offered Pinzone a fine lunch with wine, provided he would forget Church and Mrs. Malagna and go birdnesting with us in the woods. There was a gleam in his eye as he accepted. He ate our lunch and did not stint his appetite; making serious inroads on our allowance for the month. Then he joined us on our escapade, hunting with us for fully three hours, helping us to climb the trees and even going up himself. On our return home, mother asked after Mrs. Malagna and questioned us about Confession. We were thinking up something to say, when Pinzone, with the most brazen face in the world, told the whole story of our day without omitting one detail.

The punishments we inflicted for this and similar treachery never won us a decisive armistice; though the tricks we played on him were not wanting in a certain devilish ingenuity. Just before supper time, for instance, Pinzone would wait for the bell by taking a little nap on the couch in our front hall. One evening, of a wash day, when we had been put to bed early for some prank or other, we got up, filled a squirt gun with water from the wash, stealthily crept up to him and let him have it full in the nostrils. The jump he gave took him nearly to the ceiling!

What we learned with such a teacher can readily be imagined; though it was not all his fault. Pinzone had a certain erudition, among the classic poets; and I, who was much more impressionable than Berto, managed to memorize a goodly number of verses — especially charades and the baroque poetry of old. I could recite so many of these that mother was convinced we were both progressing very well. Aunt Scolastica, for her part, was not deceived; and she made up for the failure of her plans for Pomino, by trying to set Berto and me in order. We knew we had mother on our side, however and paid no attention to her. So angry was she at this scorn of her interest in ns that I am sure she would have given us both the thrashings of our lives had she been able ever to do so without mother’s knowing. One day, when she was leaving the house in rage as usual, she happened to encounter me in one of the deserted rooms. I remember that she seized me by the chin and tightening her fingers till it hurt, she said: “Mamma’s little darling! Mamma’s little darling!”; then she lowered her face till her eyes were looking straight into mine; and a sort of stifled bellow escaped her: “If you were mine... . Oh, if you were mine....! ”

I can’t yet understand why she had it in for me especially. I was a model pupil for Pinzone, as compared with Berto. It may have been the rather innocent face for which I have always been noted; an innocence accentuated rather than not by the pair of big round glasses they had fitted to my nose to discipline one of my eyes which preferred to choose, independently of the other, the objects it would look at.

Those glasses were the plague of my life; and the moment I escaped from the authority of my elders, I threw them away, restoring a longed-for autonomy to the oppressed member. As I viewed the matter, I was never destined to be a wonder for good looks, even with both eyes straight. Why go to all that trouble then? I was in good health! Never mind painting the lily!

By the time I was eighteen, a red curly beard had come to monopolize most of my face, to the particular disadvantage of a mere dot of a nose which tended to lose its bearings somewhere between that fulsome thicket and the spacious clearing of a rather impressive brow. How comforting it would be if we could only choose noses to match our faces! Imagine a man with an enormous proboscis quite out of keeping with lean wizened features. To such a man I would have said: “Look here, friend, you have a nose that just suits me. Let’s exchange! It will be to the advantage of both of us.” For that matter I could have improved in the selection of many other parts of my physique; but I soon understood that any radical betterment was out of the question. I grew reconciled to the face the Lord gave me and dismissed the matter from my mind.

Brother Roberto, on the contrary, was not so easily distracted. As compared with me, he was a handsome well-built lad; and unfortunately, he knew; it. He would spend hours in front of a mirror combing his hair and dandying up in every way. He invested a mint of money in neckties, linen and other articles of dress. On one occasion he angered me with the fuss he made over a new evening suit for which he had bought a white velvet waistcoat. To spite him, I put the thing on one morning and went hunting in it.

“The Mole” meantime was not idle. Every season Malagna would come around complaining of the bad crops and getting mother’s consent to a new mortgage he was forced to take out. Now it would be repairs on a building; now additional drainage for a field; now the “extravagance of the boys.” A visit from him meant the certain announcement of another catastrophe.

One year a frost (as he said) ruined our olive groves on the “Shoreacres”; then the philloxera destroyed our vineyards on “The Spur.” To import American roots (immune from this plague of the vines) we were obliged to sell one farm and then a second and then a third. Mother was sure that someday Malagna would find our pond at “The Coops” dried up! As for Berto and me, I suppose we did spend more money than was wise or necessary; but that does not alter the fact that Battista Malagna was the meanest swindler that ever disgraced the surface of this planet. Words more severe than these I could not charitably use toward a man who eventually became a relative of mine by marriage.

So long as mother was alive, Malagna allowed us to feel no discomforts. Indeed he put no limit to our caprices and expenditures. But that was just a blind to conceal the abyss into which, on my mother’s death, I alone was to be plunged.

I alone ... because Berto was shrewd enough to make a profitable marriage in good season. Whereas my marriage... *

“I ought to say something about my marriage, oughtn’t I, Don Eligio?”

Don Eligio is up on his ladder again, continuing his inventory. He looks around and calls back:

“Your marriage ? Why of course! The idea! Avoiding everything improper, to be sure....”

“Improper! That’s a good one! You know very well that. ...”

Don Eligio laughs and all this little deconsecrated church laughs with him... . Then he continues:

“If I were you, Signor Pascal, I’d take a peep at Boccaccio or Bandello, in passing... . That would sort of get you into the spirit of the thing...

Don Eligio is always talking about the “ spirit of the thing/ ’ the tone, the flavor, the style... Who does he think I am? D’Annunzio? Not if I can help it! I am putting the thing down just as it was; and it’s all I can do, at that. I was never cut out to be a literary fellow... . But having once begun my story, I may as well continue, I suppose.

IV - Just as It Was

I was out hunting one day, when I came upon a scarecrow in an open field. A short pudgy figure it was, stuffed with straw and with an iron pot inverted on the upright for a hat. I stopped, as a whimsical notion suddenly flitted through my head.

“I have met you before,” said I. “An old acquaintance ! “

After a moment I burst out:

“Try the feel of this, Batty Malagna!”

A rusty pitchfork was lying on the ground nearby. I picked it up and ran it into the belly of the “man”; with so much zest, moreover, that the pot was almost shaken from its perch!

Yes, Batty Malagna himself; the way he looked when sweating and puffing in a long coat and a stiff hat he went walking of an afternoon! Everything was loose, baggy, slouching about Batty Malagna. His eyebrows seemed to ooze down his big fat face, just as his nose seemed to sag over an insipid mustache and goatee. His shoulders were a sort of drip from his neck, his abdomen a sort of downflow from his chest. This belly of his was balanced — precariously — on a pair of short stubby legs; and to make trousers that would fit these along with the paunch above, the tailor had to devise some- thing extremely slack at the waist. From a distance Batty looked as though he were wearing skirts or at least as though he were belly all the way down.

How Batty Malagna, with a face and a body like that, could be so much of a thief, I cannot imagine. I always supposed thieves had a distinctive something about their appearance or demeanor, which Batty seemed to lack. He walked with a waddle, his belly all a-shake and his hands folded behind his back. When he talked, his voice was a kind of muffled bleat blubbering up with difficulty from the fat around his lungs. I should like really to know how he reconciled his conscience with the depredations he made upon our property! He must have had very deep and devious reasons, for it was not from lack of money that he stole. Perhaps he just had to be doing something out of the ordinary to make life interesting, poor devil.

Of one thing I am convinced: he must have suffered grievously, inside, from the lifelong affliction of a wife whose principal occupation was keeping him in his place. Batty made the mistake of choosing a woman from a social station just above his own (this was a very low one indeed.) Signora Guendolina, married to a man of her own sphere, would probably have made a passable helpmeet; but her sole service to Batty was to remind him on every possible pretext and occasion that she was of a good family and that in her circles people did so and so. So and so, accordingly, Batty tried his best to do. No bumpkin ever set out to become a “gentleman” with more studious application. But what a job it was! How it made him sweat — in summer weather!

To make matters worse, my lady Guendolina, shortly after her marriage to Malagna, developed a stomach trouble which was destined to prove incurable; since entirely to master it required a sacrifice greater than her strength of will: abstinence, namely, from certain croquettes she knew how to make with truffles; from a number of peculiarly ingenious desserts; and, above all else, from wines. Not that she ever abused the latter! I should say not! Guendolina was a lady and self-control is a test of breeding! But a cure of the ailment in question demanded total avoidance of strong drink.

As youngsters, Berto and I were sometimes asked to stay to dinner at Malagna’s house. Batty would sit down at table and pitch in, meanwhile lecturing his wife (with due regard for reprisals, of course) on the virtues of abstemiousness.

“I for my part,” he would say (balancing a mouthful on his knife), “fail to see how the pleasure of tickling your palate with something you like to eat” (transferring the morsel to his mouth) “is worth buying at the price of a day in bed. There’s no sense in it! Iam sure that if I” (wiping his plate with a piece of bread) “gave way to my appetite like that, I should feel myself less of a man. Damn good, this sauce today, Guendolina. Think I’ll try just a little more of it — just a spoonful, mind!”

“No, you shall not have another bit,” his wife would snap back angrily. * ‘ The idea! I wish the Lord would give you one good cramp like those I have! That might teach you to have some regard for the woman you married! “

“Why, what in the world, Guendolina ... ? Some regard for you?” (meanwhile pouring himself a glass of wine).

Guendolina would answer by rising from her place, snatching the glass from his hands and emptying it ... out of the window.

“Why ... what’s the matter? Why did you do that ? ”

“Because!” says Guendolina. “You know very well that wine is poison to me, poison! If you ever see me with a glass of wine — well — you just do what I did. You take it and throw it out of the window too!”

Sheepish, mortified but making the best of it, Malagna would look first at me, then at Berto, then at the glass, then at the window.

“But, dearest, dearest, are you a child? You expect me to force you to be good? Oh, I say! You ought to be strongminded enough to control your little weaknesses. “

“While you sit there enjoying yourself? While you sit there smacking your lips, holding your glass up to the light, clinking it with your spoon — just to torment me? Well, I won’t stand it! That’s what I get for marrying a man of your antecedents! ...”

Well, Malagna went so far as to give up wine, to please his wife and set her a good example! I leave it to you: a man who would do that is likely to steal, just to convince himself that he amounts to something.

However, it was not long before Batty discovered that his wife was drinking behind his back; as though wine consumed in that way would not do her any harm. Whereupon Batty took to wine again himself; but at the tavern, so as not to humiliate his Guendolina by showing that he had caught her cheating. And a man who would do that ... !

Eventual compensation for this perennial affliction Batty Malagna hoped to find in the advent of a male heir to his family. That would be an excuse, in his own eyes and in the eyes of anybody, for all his thievery from us. What may a man not do to provide a future for his children? But his wife, instead of getting better and better, got worse and worse. Perhaps he never mentioned this burning subject to her. There were so many reasons why he should not add that worry to her troubles. Ailing, almost an invalid in the first place! Then she might die if she tried to have a child! No: God forbid! Batty would be resigned! Each of us has a cross to bear in this world!

Was Malagna quite sincere in this considerateness? If so, his conduct did not show it when Guendolina died. To be sure, he mourned her loss! Oh yes, he wept till it seemed his heart would break! And he was so thoughtful of her memory that he refused to put another “lady” in the place which she had occupied. No, no, I should say not! And he might have, you know, he might have — man in his position in town and with plenty of money by this time! No, he married — a peasant girl, the daughter of the farmer who worked one of our estates — strong healthy thing, good-natured, good housekeeper — so that everyone could see that what he wanted was children and the right woman to bring them up. If he waited hardly till Guendolina was cold in her grave, that was reasonable, too. Batty was getting on in years and had no time to waste.

I had known Oliva Salvoni well since I was a little boy and she a little girl. Daughter of Pietro Salvoni (the land he worked was the farm of ours which we called “The Coops”), she had been responsible for the many hopes I had aroused in poor mother in my time — hopes that I was about to settle down and take an interest in our property, even turn to farming which I had suddenly begun to like so well. Dear innocent mamma 1 It was, of course, my terrible Aunt Scolastica who shortly disabused her:

“But don’t you see, stupid, that he’s always hanging around Salvoni’s?”

“Yes, why not? He’s helping get the olives in!”

“I Helping take an Olive in! One Olive, do you hear, cabbage-head!”

Mother gave me a scolding that she thought would last me a long time: the mortal sin of leading a poor girl into temptation, of ruining an innocent creature I could never marry ... that kind of talk, you understand... .

I listened respectfully. Really there was not the slightest danger in the world. Oliva was quite able to take care of herself: and one of her charms lay precisely in the ease and independence born of this assurance, which enabled her to avoid insipid reticences and affected modesty. How she could laugh! Such lips as hers I have never seen before nor since. And what teeth! From the lips I got not the suggestion of a kiss; from the teeth — a bite once, when I had seized her by the wrists and refused to let her go short of a caress upon her hair! That was the sum total of our intimacy.

So this was the beauty (and such a youthful, fresh and thoroughly charming beauty!) that Malagna took to wife. Oh yes, I know ... but a girl can’t turn her back on certain opportunities! She knew very well where that rascal got his money. One day, indeed, she told me exactly what she thought of him for doing it. Then later on, because of that very money, she married him... .

However, one year, two years, went by — and Malagna’s heir was still wanting.

During the period of his first marriage Malagna had put all the blame on Guendolina and her stomach trouble; but not even now did he remotely suspect that the fault might be his own. He began to scowl and sulk at Oliva.

“Nothing?”

“Nothing!”

From the end of the third year his reproaches became quite undisguised. Soon he was actually abusing her, shouting and making scenes about the house and claiming that she had made a show of her good health and good looks, to swindle him — a plain downright swindle, yes sir! What had he married her for? A woman of her class! Putting her in the place a lady — a real lady, sir — had held! — And if it hadn’t been for that one thing, do you suppose he would ever have thought of doing such a slight to the memory of the distinguished “lady” who had been his first wife?

Poor Oliva said nothing, not knowing what there was to say, in fact. She just came to our house to tell my mother all about it; and mother would comfort her as best she could, assuring her there was still some hope, since Oliva was a mere slip of a girl... .

“Twenty, about?”

“Twenty-two! ”

Oh, why so downhearted then? Children came sometimes, ten, fifteen, twenty years after a woman’s marriage! And her husband? Malagna was getting on in years, that was true; but... . Oliva, from the very first, had had her doubts, wondering whether . , . well, how should she put it? ... whether ... it might not be his fault ... there! But how prove a thing like that? Oliva was a woman of scruples. On marrying Malagna for his money and for nothing else she had determined to play absolutely fair with him ... and she would not deceive him even for the sake of restoring peace to her household... .

“How do you know all that ? ’’ asks Don Eligio.

“Huh! How do I know! I have just said that she came to our house to discuss the matter with my mother. Before that I said I had known her all her life. Then, now, I could see her with my own eyes crying her heart out, all on account of that disgusting old thief! Finally... . Shall I say it right out, Don Eligio!”

“Say it just as it was!”

“Well, she said no! That’s putting it just as it was! “