Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The intention of this book is to give an overview of Alfred Adler's fundamental ideas tracing the development of his theory of psychotherapy during the years between 1912 and 1937: the compensation of inferiority feeling and the founding of the concept of community feeling in emotional experience, in body and mind and in the philosophy of life. Adler doesn't adopt an objectifying external perspective; he doesn't see the overall context from outside from a reflective distance, but rather looks from his experience of human society onto the contingency of human life. All of his theoretical concepts are bound up in this holistic approach. Adler's theoretic development shows that the basic concepts of Individual Psychology are not only descriptive labels; they grow out of inner experience. Adler expresses harsh criticism of all forms of community governed by the "will to power" and pleads for a cooperation in terms of real social interest or community feeling. This E-Book is a revised edition of the introduction to the third volume of the Alfred Adler study edition published in 2010. A new chapter has been added: »The relational dimension of Individual Psychology«. The step-by-step development of Alfred Adler's thinking is described following lectures and papers collected in the study edition. The quotations are taken from the original versions of Adler's papers.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 144

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Gisela Eife

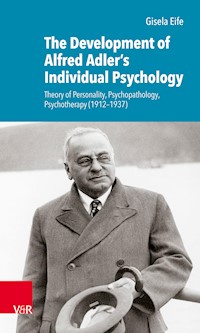

The Developmentof Alfred Adler’sIndividual Psychology

Theory of Personality, Psychopathology, Psychotherapy (1912–1937)

Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek:

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data available online: http://dnb.de.

© 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Theaterstraße 13, D-37073 Göttingen

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission from the publisher.

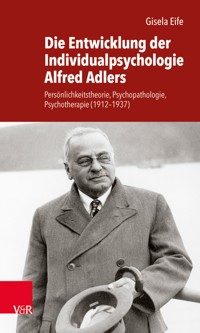

Cover image: Alfred Adler, around 1935/akg-images/Imagno

Typesetting by SchwabScantechnik, GöttingenEPUB production by Lumina Datametics, Griesheim

Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Verlage | www.vandenhoeck-ruprecht-verlage.com

ISBN 978-3-647-99891-6

Table of Contents

Preface

The Dual Dynamic: the Core of Adler’s Theory

1Compensation

1.1The Neurotic Form of Compensation – The Inferiority-Compensation-Dynamic

Digression 1: Trauma as a Cause of Neurosis?

Digression 2: The Negativity of Neurosis

1.2The General Form of Compensation

2Communality

2.1The Developmental Line of Movement (1926–1933)

2.2The Developmental Line of Emotional Experience (1923/1926–1933)

2.3The Developmental Line of Community Feeling (1923–1933)

3The Junction of the Dual Lines: Compensation and Communality

3.1The Unconscious Life Style as the Ego

3.2The Immanent Characteristics of Life

3.3The Configuration of Life Force in the Dual Dynamic

4Treatment Instructions

4.1Treatment Instructions from the “Individual Psychological Treatment of Neurosis” (1913a)

4.2Treatment Instructions Between 1926 and 1931

Prospect: The Relational Dimension of Individual Psychology

1The Generation of Experience

1.1The Mind-Body-Processing of Experience

1.2The Experience of Co-Movement and Affect Attunement

1.3The Experience of Wholeness

2The Intersubjective Development of the Life Style

3The Interaction of Life Styles and the Meeting of Therapist and Patient

References

The Collected Clinical Works of Alfred Adler

Alfred Adler Studienausgabe (Study Edition)

Adler’s Writings

Scientific Literature

Preface

This book is a revised edition of my introduction to the third volume of the German Alfred Adler Study Edition1 “Persönlichkeitstheorie, Psychopathologie, Psychotherapie” (Adler, 2010). A new chapter has been added: “The relational dimension of Individual Psychology”.

The starting point of Alfred Adler’s psychotherapeutic theory is well documented in his major work “The Neurotic Character” (Adler/Stein, 1912a/2002a)2. The further elaboration is made accessible particularly in the third volume (Adler, 2010a) of the German Alfred Adler Study Edition and in Henry Stein’s “The Collected Clinical Works of Alfred Adler” (Volume 1–9). Substantial aspects can also be taken from “Der Sinn des Lebens” (Adler, 1933b). In summary, the following concepts present the essentials of the development of Adler’s theory: the compensation of inferiority feeling and the concept of community feeling anchored in emotional experience, in body and mind and in the philosophy of life.

Many influences, impulses and stimulations contributed to the production of this book. I would like to thank all my colleagues who encouraged my individual psychological development. Conversations with my partner, a psychoanalyst and a researcher of Master Eckhart’s writings, Karl Heinz Witte, enriched and inspired me. I myself have translated the German version of this e-book and owe heartfelt thanks to Caroline Murphy for her supervising and correcting my English. Also, I want to thank Corina Gogalniceanu, Erik Mansager, a Classical Adlerian Depth Psychotherapist (CADP), and Paola Prina-Cerai, a member of the editorial board of the UK Adlerian Year Book, for their interest and support. And finally, I want to thank my lector Ulrike Rastin for her kind cooperation and helpfulness.

1Starting in 2007, an Alfred Adler Study Edition has been published in German, edited by Karl Heinz Witte.

2Starting in 2002, a new English translation of Adler’s writings has been published in English, edited by Henry Stein. Most of Adler’s quotations are taken from Stein’s edition; a few quotations are only published in the German Study Edition. The small letter behind the year of publication is part of the German classification of Adler’s papers.

The Dual Dynamic: the Core of Adler’s Theory

Adler’s theory discusses the modality whereby the human being masters his or her3 life in the world. He sees the life of the individual as well as that of the masses as a “compensation process, attempting to overcome felt or alleged ‘inferiorities’ in a physical or psychological manner” (Adler/Stein, 1937g, p. 215).

For Adler, the feeling of inferiority is “a chance and necessity for the human being, the onset, the impetus for human development” (Adler, 1926k, p. 258)4. It is a “stimulus” (Adler, 1933l, p. 568)5 and an “incentive” (Adler, 1926k, p. 258) for the compensation process, the striving for a goal of security and superiority. Thus, Adler bases his concept of neurosis in a higher-ranking motive, that is the goal-orientation of the human being, instead of a partial motive (Libido) or a system of several motives.

At the beginning, Adler called this compensation process the “life plan”, starting in 1926, he used the term “life style”. As a result of his experience during the First World War, in which he felt the lack of a common ground for humanity, Adler introduced the term community feeling6 in 1918.

The introduction of community feeling manifests a change in the development of Adler’s theory. He discovered that psychic health cannot be achieved by a correction of psychic disorders. A patient’s health depends on the degree of his or her community feeling. Since the introduction of community feeling Adler’s theory is a value psychology, community feeling serves as a corrective and a criterion.

In 1918, Adler also realized a “dual relatedness” of Dostoyevsky’s heroes: “Our feeling of dual personality [Adler uses dual relatedness]7 is inherent in every character and fixed on two points that we can sense. Every Dostoyevsky hero moves assuredly in an area that, on the one hand, is limited by an isolated heroism, within which the hero transforms himself into a wolf and, on the other hand, the hero is contained behind a line drawn by Dostoyevsky where there is love of one’s fellow human beings. This dual personality [dual relatedness] gives strength and security to his characters and anchors them firmly in our minds and feelings” (Adler/Stein, 1918c, p. 121). “Countering his demand for power […] is the experience of the overwhelming necessity for the community’s aspirations” (Adler/Stein, 1918h, p. 132).

Each character is related to two fixed points in which Adler sees the contrast: isolated heroism versus brotherly love. These two tendencies in human life resemble Melanie Klein’s concept of the depressive and paranoid-schizoid position (Klein, 1944/1975, p. 317), but for Adler these concepts gain a foundation in his philosophy of life.

At the moment when Raskolnikov changes from one relatedness to another, “he wants to cross the line laid down by his life thus far, fashioned on the basis of his social feeling and his life experiences” (Adler/Stein, 1918h, p. 115). This line can be a turning point of the life-movement, a way out of the compensation dynamic into a life determined by community feeling. Adler did not pursue these thoughts at that time. Not before 1929 did he coin the term “dual dynamic” for these two tendencies in human life. He never gave a definition, but many thoughts went in this direction in his investigation of human life (see chapter 3).

In 1918, Adler recognizes, how the human being is related to these two fixed points: isolated heroism versus brotherly love. At that time, he does not yet dissolve these points into movement – a phenomenon that he will conceptualize towards the end of the 1920s. The remarkable thing is that he speaks about relatedness referring to the relationship of two characters and, later on, only about forms of movement. Firm structures are also dissipated in quantum physic (Görnitz a. Görnitz, 2008); only relations or movements are left. Adler knew about the new scientific findings of that time.

In 1914, he criticized “the outmoded and antiquated natural science with its rigid systems”. “Such an approach eliminates the application of subjective thought and empathy with the patient, which in fact firmly establishes the connection”. This kind of science “today has universally been replaced by a view that […] seeks to understand life and its variations as a unity” (Adler/Stein, 1914h, p. 26).

In 1926, Adler again refers to this dual relatedness, this “striving for superiority […] and the devotion to community that relates this individual to others” (Adler/Stein, 1926m, p. 165). In 1929, Adler is able to concisely formulate the dual dynamic which captures the two kinds of relatedness as movements and which, above all, sees both movements in every phenomenon: It is hence possible to detect “that the ways of expressing social interest [Gemeinschaftsgefühl] and the striving for mastery run in parallel lines in two or more forms” (Adler/Stein, 1929f, p. 94).

“Consequently, in every psychological expression, we can find next to a degree of social interest [Gemeinschaftsgefühl] the striving for superiority. We can be satisfied with our examination only when we have seen in the neurotic symptom this dual dynamic in exactly the same way as in any other human expressions” (p. 94).

Adler describes two forms of movement in every phenomenon, one “in accordance with social interest [Gemeinschaftsgefühl]” and the other “in accordance with personal power” (Adler/Stein, 1928m, p. 84). The term “dual dynamic” does not mean two oppositional forces, but one life force causing individuals to live in a self-centered and/or social way.

In formulating the concept of the dual dynamic, Adler tries to understand human life totally in one concept, in a conceptual design of the philosophy of life. All of his theoretical directions are connected in this view. In my opinion, this is the main feature of Adler’s holistic view: All of human life is determined by this dual dynamic. From this follows that all of Adler’s terms in their existential meaning are to be understood from this dynamic. Therefore, this concept represents for me the inner coherence of Adler’s theory.

Next, I shall examine these aspects and tendencies:

–Compensation,

–Communality, and

–Starting in 1931, the merging of both.

Adler first investigates the compensatory neurotic striving.

1Compensation

Adler starts with organic compensation (Adler/Stein, 1908e). As early as 1908, Adler realised that compensation occurred by “increased growth or functions” (Adler/Stein, 1908e, p. 78). A representative feature of inferior organs would be, in his opinion, the fact that they are not fully differentiated in their embryonic development; however, this deficiency can be compensated for in their further development.

Adler transposes the organic compensation into the psyche, into the psychological development as well. The incentive for compensation would then be inferiority and the feeling of inferiority. “The feeling of inferiority has grown out of real impressions that are later tendentiously adhered to and reinforced” (Adler/Stein, 1913a, p. 118). Thus, the feeling of inferiority must be compensated for.

Adler found a general principle of human life in this compensation, which reveals the existential approach in his dynamic. For him, the individual creates unconscious conceptions of him- or herself, how he or she wants to be, in order to be able to live in this world.8

In his early writings, the compensation is called “the masculine protest” and in “The Neurotic Character” (Adler/Stein, 1912a), it appears as “the will to power” and “the striving for personal superiority”. The masculine protest is only mentioned twice after this, in two articles dating from 1930 (Adler 1930n, p. 373)9 and 1931 (Adler/Stein, 1931n, pp. 21–24). It would not be anything other than “the ascertainment of a striving for power compelled by social underestimation and undervaluation of women in our culture” (Adler, 1930n, p. 382).

“The will to power” is no longer mentioned in the following articles. Adler did not give up this concept, but he changed the name into the terms “striving for superiority”, for “godlikeness” and, starting in 1926, into “striving for overcoming and perfection”.

Adler’s teaching of neurosis was presented in his major work “The Neurotic Character” (Adler/Stein, 1912a) in its final version and never changed its fundamental structure after that.

Adler first described the neurotic form of the striving for compensation, and then, starting in 1926, the human condition in general.

1.1The Neurotic Form of Compensation – The Inferiority-Compensation-Dynamic

This chapter includes topics that Adler regarded as essential. They were already discussed in Adler’s major work in 1912 and were again and again depicted and expanded throughout his life. These topics describe the neurotic life style and are to be understood from Adler’s holistic view and from his fundamental unconscious dynamic that he later called the “dual dynamic”. The topics are organ inferiority, psychic inferiority, fiction, finality, personality ideal, compensation, unity of personality, will to power, individuality, subjective thinking and feeling, conscious and unconscious, experience of infancy and goal-orientation, creative power, body and psyche.

Adler takes “organ inferiority” (Adler/Stein, 1908) as the basis for neurosis; it is extended by the psychological dimension of inferiority feeling, but Adler’s interest for organ inferiority can be seen throughout his entire work.

Because the neurotic feels inferior towards life, he or she is striving “to prove his ability to cope with life” (Adler/Stein, 1913a, p. 118) and to secure it. Adler even discusses “a compulsion for securing superiority” (p. 116). This compulsion “is so strong that, aside from what appears on the surface, every psychological phenomenon under comparative psychological analysis also displays another trait: escaping from a feeling of weakness in order to gain the upper hand, lifting oneself from below to above” (p. 116).

Each emotional expression of the neurotic carries two premises: “A feeling of not having measured up to, of being inferior, and a compulsive [Adler: “hypnotisierendes, zwangsmäßiges”] striving for a goal of godlikeness” (Adler/Stein, 1914k, p. 53).

Adler uses the term “real need [Not]10” (Adler/Stein, 1923f, p. 30), the “needs and helplessness of a child” (Adler/Stein, 1923c, p. 19), and adds that the feeling of inferiority also originates in the “vulnerability of the human organism in the face of nature” (Adler/Stein, 1923f, p. 30).

In his opinion, being human means “having a feeling of inferiority. Nobody is able to free himself from a feeling of inferiority towards nature, towards the difficulties of life and of living together, and because of mortality” (Adler, 1926k, p. 258).

The answer to this existential experience lies in the individual’s processing of the experience. And this answer is sought in the “fixed point outside” (Adler/Stein, 1912a, p. 41) the personality, one of Adler’s postulates. Psychic tendencies combine and form a guiding “fiction”; here Adler is making a reference to Vaihinger (1911).

Adler calls this unconscious conception, which protects individuals from the chaos and insecurity of life, a mental orientation on “a specific fixed point outside his own person” (Adler/Stein, 1912a, p. 41). That is the reason why, according to the phenomenological tradition, this outside point can be viewed as an immanent transcendence, an “intentionality focused on the outside without transcending the area of subjectivity” (Witte, 2008, p. 162). This immanent transcendence is an essential feature of the individual as a subject. The upward-striving towards this goal is the driving and organizing force of the creation of the personality.

According to Adler, the psyche is both an attack and defence organ (Adler, 1930n, p. 374). None of us can exist without a goal. The fact that Adler understands the individual in his or her finality is the most important characteristic of Individual Psychology. He writes that: “It is not possible for us to think, feel, desire or act without envisioning a goal” (Adler/Stein, 1914h, p. 27).

This goal-oriented striving offers a unifying direction to life’s movement and determines the unity of personality. Adler hereby relied on Kant (Adler, 1933l, p. 566) and his theory of the “a priori” forms of intuition (Adler/Stein, 1932g, p. 66) as well as on the “stabilization of the unity of the personality […], whose absence would have made psychological analyses inconceivable” (Adler, 1926k, p. 252). Unity is “the entrance to Individual Psychology, its necessary premise” (p. 252).

According to Adler, the goal-directed striving gives a uniform direction to the human life-movement and conditions the unity of the personality. “Coherent conduct of this kind can only be understood if one presupposes that the child has found a specific, fixed point outside his own person that he is striving after with the energy of his psychic development” (Adler/Stein, 1912a, p. 41).

This goal-setting maintains the unity of the personality in spite of a possible change in symptoms and neurosis. This uniform personality persists, “without being consciously aware of and without being an object of critical perception” (Adler, 1926k, p. 256).

Many of Adler’s phrasings deal with this reference point lying outside the personality system: initially it is the goal of the striving for security; it is also called the guiding fiction, the personality ideal, the goal of superiority and godlikeness. In the 1930s, this reference point appears as “the individual’s eternal task” (Adler/Stein, 1931n, p. 21), the distant goal of developing an ideal community “sub specie aeternitatis” (Adler/Stein, 1933i, p. 98).

We can experience a homogeneous unity with our own self when we identify with our unconscious individual fictional goal. But this feeling-of-being-identical-with-ourselves as identity will be drastically challenged.

There is no natural, just a fictional identity.11 In 1931, Adler states that the unconscious”I” is identical with the life style and comprehensible only in its movement or stylizing “so that we confront [Adler added “over and over again”] the individuality, the life style of the person, his I” (Adler/Stein, 1931l, p. 3).