13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

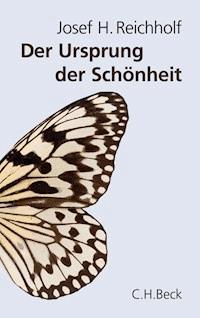

In the last fifty years our butterfly populations have declined by more than eighty per cent and butterflies are now facing the very real prospect of extinction. It is hard to remember the time when fields and meadows were full of these beautiful, delicate creatures – today we rarely catch a glimpse of the Wild Cherry Sphinx moths, Duke of Burgundy or the even once common Small Tortoiseshell butterflies. The High Brown Fritillary butterfly and the Stout Dart Moth have virtually disappeared.

The eminent entomologist and award-winning author Josef H. Reichholf began studying butterflies in the late 1950s. He brings a lifetime of scientific experience and expertise to bear on one of the great environmental catastrophes of our time. He takes us on a journey into the wonderful world of butterflies - from the small nymphs that emerge from lakes in air bubbles to the trusting purple emperors drunk on toad poison - and immerses us in a world that we are in danger of losing forever. Step by step he explains the science behind this impending ecological disaster, and shows how it is linked to pesticides, over-fertilization and the intensive farming practices of the agribusiness.

His book is a passionate plea for biodiversity and the protection of butterflies.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 495

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Part I: The Biodiversity of Lepidoptera

A Review of 50 Years of Butterfly and Moth Research

Insects fly towards UV light

Urban Lepidoptera: more common than expected

Death’s head hawk-moth: a guest that can barely live with us anymore

The Fascinating Life of Aquatic Moths

Evenings at the pond

The hidden lives of the little nymphs

How the caterpillar breathes under water

Up and away in an air balloon

The advantages of living in water

A place to live or an ‘ecological niche’

The destruction of the biotopes of the little nymphs

The Benefits of Being Attracted to Light

Like moths to a flame

The red blindness of butterflies

The Strange Behaviour of the Purple Emperor

Butterflies on drugs

Psychedelics in the insect kingdom

The Nettle-feeding Lepidoptera: An Instructive Community

Nettles: indicators of overfertilization

Nettles escape defoliation

Maize: damaged beyond repair

Cabbage whites: parasites and protection

The mass flight of the map butterfly: singularities in the realm of the butterflies

Does climate change affect the seasonal morphs of the map butterfly?

Nature is too diverse for simple generalizations

The Great Migrations of the Butterflies

The migratory flights of the painted ladies

Small tortoiseshells as travellers

Butterfly invasions

Poisonous Butterflies and Moths: From the Cabbage White to the Six-spot Burnet

Cabbage whites on the Dalmatian coast

Whenever it rains in the desert …

Which factors affect the reproduction of butterflies, and when?

Useful models

The need to go slow

Poison in the body

The Secret Life of Small Ermine Moths

The bird-cherry, a tree of the riparian woods

Toxins in bird-cherries

The life history of the caterpillars of the ermine moth

Helpful hungry caterpillars

Between parasitism and population explosion

Longer-term population cycles

Coppice management and its consequences

Generations and multiyear cycles of ermine moths

Parasitoids on other ermine moths

The lifecycles of butterflies and moths

Hardy Winter Moths

Life at the edge of winter

The mastery of seasonal niches

Why female winter moths do not need wings

Deforestation, poison and the decline of the codling moth and the winter moth

The common quaker moth in early spring

Brimstones: The First Spring Butterflies

Butterfly attacks

The problem with early flight

Müllerian mimicry

The critical factor of spring weather

‘Balance’ in nature

Part II: The Disappearance of Lepidoptera

Assessing the Abundance and Occurrence of Butterflies: A Major Challenge

Starting with 1,000 watts

How to successfully attract moths to light

Change and continuity

All praise to those who helped us with identification problems

Butterfly and Moth Names

The Decline of Moths and Butterflies

The village outskirts and the open fields

Findings in the riparian woods

The findings from Munich

The decline in species diversity

Warm summers and what they mean for the moths and butterflies

The Metropolis: The End of Nature or Salvation of Species Diversity?

The advantage of structure

Monocultures produce pests

Cities as islands of warmth

Overfertilized, poisoned land

Nature-friendly cities

The Inhospitality of the Countryside

From idyll to slurry

Monocultures and changes to the ground-level microclimate

The cooling of fields and forests

Increased growth reduces the abundance of moths and butterflies in the riparian woods

Boundary ridges in the fields and meadows: a supportive network

‘Infilling’ and ‘compensating areas’

The ‘nutritional condition’ of the landscape

The disappearance of the cockchafers

The turning point for our farmers: the 1970s

The Krefeld Study

A subsidy system without an exit mechanism

Nature conservation and nature enthusiasts

The Devastating Effect of Communal Maintenance Measures

The End of the Night: The Role of Light Pollution

Summary: A Cluster of Factors

The Disappearance of Moths and Butterflies and Its Consequences

What We Can Do about the Disappearance of Moths and butterflies

The Beauty of Moths and Butterflies

Two Findings in Place of an Epilogue

Select Bibliography

Index

Ebook plates

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Begin Reading

Two Findings in Place of an Epilogue

Select Bibliography

Index

Ebook plates

End User License Agreement

Pages

iii

iv

vii

viii

ix

x

1

2

3

4

5

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

137

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

The Disappearance of Butterflies

Josef H. Reichholf

Translated by Gwen Clayton

polity

Originally published in German as Schmetterlinge: Warum sie verschwinden and was das für uns bedeutet by Joseh H. Reichholf © 2018 Carl Hanser Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, München

This English edition © 2021 by Polity Press

The translation of this work was funded by Geisteswissenschaften International – Translation Funding for Work in the Humanities and Social Sciences from Germany, a joint initiative of the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, the German Federal Foreign Office, the collecting society VG WORT and the Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels (German Publishers & Booksellers Association).

Excerpt from Vergängliche Spuren by Miki Sakamoto reproduced with permission of Verlag Kessel. © Verlag Kessel, Remagen 2014. All rights reserved by and controlled through Verlag Kessel. www.forestrybooks.com

Excerpt from ‘Blauer Schmetterling’, from: Hermann Hesse, Sämtliche Werke in 20 Bänden. Herausgegeben von Volker Michels. Band 10: Die Gedichte © Suhrkamp Verlag Frankfurt am Main 2002. All rights reserved by and controlled through Suhrkamp Verlag Berlin.

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press101 Station LandingSuite 300Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-3981-9

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Reichholf, Josef, author.Title: The disappearance of butterflies / Josef H. Reichholf ; translated by Gwen Clayton. Other titles: Schmetterlinge. EnglishDescription: Cambridge, UK ; Medford, MA : Polity Press, [2020] | Originally published in German as Schmetterlinge : Warum sie verschwinden and was das fur uns bedeutet by Joseh H. Reichholf 2018 Carl Hanser Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Munchen. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and CIP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed.Identifiers: LCCN 2020012872 (print) | LCCN 2020012873 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509539819 (epub) | ISBN 9781509539796 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509539796q(hardback) | ISBN 9781509539819q(epub)Subjects: LCSH: Butterflies. | Butterflies--Ecology. | Butterflies--Conservation.Classification: LCC QL543 (ebook) | LCC QL543 .R4513 2020 (print) | DDC 595.78/9--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020012872 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020012873

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Printed endpapers: nelsonarts/iStock

Foreword

Most people in the British Isles and North America – as well as on the European mainland – are by now well aware that many species of wildlife are declining and even disappearing. Butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera) are prominent among them. The author of this authoritative book, Dr Josef Reichholf, became concerned about the decline of many species in his native Germany during his doctoral and postdoctoral research at the Ludwig-Maximilian University of Munich on moths in both rural and urban areas around that city in the 1970s and 1980s. He became aware of the staggering speed of change and its extent, mainly due to the intensification of agriculture. The subject of his doctoral research was a group of aquatic moths belonging to the Crambid family, which he studied intensively in the field at a cluster of gravel pits near his boyhood home in Bavaria. Some time after completing his thesis, Dr Reichholf was saddened to find that some of these pits had been converted to swimming pools and others infilled and returned to agriculture, mostly for the cultivation of maize. At the same time, the riparian woodlands along the River Inn, which had been a favourite wildlife haunt of his – he started out as a bird-watcher in 1958 – were being uprooted to make way for the booming and profitable cultivation of maize. With the maize monoculture came the intensive use of pesticides to control the pests that infect it.

Dr Reichholf eventually made a long-term study of the Lepidoptera in urban and suburban Munich, mainly by employing light traps, and he came to the conclusion that, although the species diversity is less in urban areas, they are doing much better in the ‘nature-friendly’ cities than they are in the ‘inhospitable’ countryside, because the former are islands of warmth (the ‘heat island’ effect) and there is a much lower use of pesticides there. He devotes the second half of the book to a critical examination of the causes of the declines in so many butterfly and moth species: these, mostly familiar to British and North American nature conservationists, include the replacement of old, traditional farming by intensive agriculture, overuse of fertilizers and pesticides poisoning the soil, deforestation and reforestation with monocultures, habitat loss, over-tidiness, light pollution and the underlying effects of climate change.

Dr Reichholf holds strong views and is outspoken in his criticism of the role of politicians and government policies with regard to the environment and its wildlife. Some nature conservationists also come in for criticism for concentrating on legally protecting species from field naturalists and collectors and for not fully recognizing that their real enemy is industrialized agriculture. Finally, he considers the consequences of the disappearance of butterflies and moths and what can be done to arrest it.

This passionate, powerful and thought-provoking book could not be more timely. It deserves to be widely read by everyone concerned about the natural environment and I am very pleased to be able to recommend it.

John F. Burton, FZS, FRES

A Vice-President of Butterfly Conservation

Acknowledgements

I owe thanks to many people – too many to be able to list them all by name. The two main forces that led to the creation of this book came from my wife and my closest friends, on the one hand, and my publisher and agent, on the other. Working together with my literary agent Dr Martin Brinkmann and my editor Christian Koth of C. Hanser Verlag was both enjoyable and stimulating. The results make me feel optimistic, despite having experienced the decline of moths and butterflies over the last 50 years, that there is at least a glimmer of hope. If such a leading German publishing house can dedicate itself so closely to the subject of the disappearance of moths and butterflies, one must believe that there are still opportunities. I am very grateful to C. Hanser Verlag for conveying such optimism.

I thank my doctoral supervisor, the late Dr Wolfgang Engelhardt, for proposing the topic of aquatic moths and the extensive engagement in nature conservation that this led to, at a time when he himself was president of the Deutscher Naturschutzring. Through his suggestion, he effectively set the course of my professional life as a zoologist. Of central importance also was the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology (ZSM): a unique institution, where, as a member, one could feel ‘butterflies’ in one’s stomach, while above, on the roof, real blue butterflies blithely flew around. It is beyond my abilities to try to put into words my gratitude for my time spent at the ZSM and my time as a teacher at both of the Munich universities, even though my essential attitude to life was formed professionally by these experiences. I am grateful to my wife, Miki Sakamoto-Reichholf, for the fact that I was able to combine them so well with my private life. She shares my enthusiasm for moths and butterflies.

It is a great pleasure to me to see my book translated into English, which opens my findings to an international audience. Some aspects, however, refer to the regional situation in Germany, especially in Bavaria and the adjacent regions of Austria. Others are of a much more widespread coverage. We are faced with the fact that the decline of butterflies, moths and other insects is a global phenomenon of our time. Many local and regional findings can be fitted together like a mosaic to create a picture that is already quite clear. It shows the continuing loss of biodiversity and natural richness.

I would like to thank Polity, especially Elise Heslinga, and the translator Gwen Clayton for their engagement. For me, it was a highly rewarding experience to work together with them in order to achieve a good translation. In my thanks I would also like to include John F. Burton for his highly valuable contributions to the English edition of my book. Last but not least, it is my hope that readers will be infected by the enthusiasm that I have felt throughout my years of research on moths and butterflies. This book is about their life and their future.

Introduction

In the last 50 years, our moth and butterfly populations have declined by more than 80 per cent. Perhaps only older people will recall a time when meadows were filled with colourful flowers and countless butterflies fluttered above. Nobody would have thought of wanting to count them then. Why would you! Butterflies belonged to summer, just like bees and wildflowers. Larks sang from early spring until mid-summer. They would sing from first light, suspended in the air over the fields. There were yellowhammers, partridges, hares. Frogs lived in the ditches and ponds. In the 1970s, treefrogs still called so loudly from a pool near my home at the edge of the fields that their chorus was audible through the veranda door during a telephone interview with the Bayerischer Rundfunk. The topic: proceedings at the Bavarian District Court regarding noise pollution caused by frogs.

I became familiar with butterflies when I was just a child. I saw dozens of large swallowtails with their distinct black lattice over pale-yellow wings. They flew to our vegetable garden to lay their eggs on carrot leaves. Their green caterpillars with red spots gave me particular pleasure when I discovered them weeks later. If I touched them near the front, they would shoot out the strangest orange-yellow fork from a wrinkle behind their head. They emitted a peculiar odour that I later learnt was a deterrent.

Blues of various species, which I could not tell apart at the time, flew over the meadows that stretched from our little house at the edge of the village to the woodland along the river. The shimmering blue butterflies were so abundant that, looking back, I could not even have estimated how many there were. One barely noticed the cabbage whites. They were part of the nature that surrounded us, like the chirruping of the field-crickets in May and June and the chirping of the grasshoppers in midsummer. I used to enjoy tickling the field-crickets out of their burrows with a stem of grass. Their bulky, brawny-looking heads amused me. There did not seem to be much going on in there – they were so easily tricked.

In the pollarded willows by the stream that snaked through the meadows behind our house, hoopoes would make their nests. With raised crests, they would stride around the grazed pastures, nodding their heads and poking around in the cowpats left behind by the cows. These birds were in the pastures during the day throughout the whole summer and far into the autumn. The air would teem with starlings. These black-feathered birds would follow the cows as if obsessed, sometimes even sitting on their backs. Every garden had at least one nestbox attached to a high pole for the starlings. When the cherries ripened, they feasted and took a significant share and made themselves heard in the process. Driving starlings away from the cherry trees was a great pleasure for older children, since they were allowed to climb right up into the tree crown, where the cherries dangled in front of their mouths. At our house, a colony of sparrows lived under the roof – a good dozen, maybe even more. They were always there, but our cat paid no attention to them. She went mouse-hunting and was very successful. A country idyll. Romanticized memories of childhood and early youth in a valley of the lower reaches of the River Inn, Lower Bavaria?

Perhaps nostalgia has affected our perception of the past. For this reason, one must be conscious of every attempt to reconstruct the ‘former’ as a basis for the ‘present’. Memory supplies whatever we would like to have had, and it tends towards nostalgia and a yearning for what is gone. Nevertheless, I shall begin this book with descriptions of the natural beauty and abundance that I once experienced myself, in part to explain why the disappearance of the butterflies affects me so deeply. The first part of the book is intended to provide the basis from which we can make a judgement about the loss of the species. I have selected my examples so that the reader need not be a specialist in order to have observed and experienced similar things. These examples come from my own work and observations in Bavaria, but could equally have been taken from similar studies elsewhere in Europe or in the British Isles.

Together, these examples ought to show that the abundance of moths and butterflies, for reasons that are yet to be explained, has nevertheless shown a generally downward trend over at least the last 50 years (bearing in mind that it has always fluctuated substantially). The causes of this are discussed in the second part of the book. In order to do this, it is crucial to distinguish ordinary fluctuations from the general trend. This is critical, not only for understanding the natural cycles, but also for identifying the correct measures required to reverse the downward trend. It will not be achieved, for example, by simply reducing the application of poisons, as worthwhile as this might be. Whatever we commonly associate with ‘green’ and ‘eco’ holds its own problems with respect to the conservation of species. The second part of the book will therefore inevitably touch on environmental policy. The ecology movement lost its claim to scientific integrity, in my opinion, when it was converted into a ‘nature religion’ through crises that lent themselves to political manipulation. I am ready to be contradicted: I am used to this and it belongs to the principle of scientific discourse. Such discourse differentiates itself from the exchange of publicly entrenched opinions by accepting better findings. This makes natural science stronger, but also increasingly unpopular. It remains qualified and flexible, while people today seem to delight in dogmatically countering one principle with another. Scepticism does not disqualify you from being a natural scientist; instead, it is the praiseworthy habit of someone who does not submit to dogmas, even if they are currently supposed to be in fashion.

The same is true for the limitation of our freedom of expression under pressure from ‘political correctness’. Whether we say ‘plant protection products’, as some demand, or ‘poisons’ does not change their effect, since that is what they are supposed to be: substances that kill what is supposed to be destroyed. Moreover, I have been unable to avoid writing in general terms of ‘agriculture’, ‘maintenance measures’ or ‘nature conservation’. Farmers, if they so choose, can farm in an insect-friendly manner; a maintenance squad that cares for roadside verges can sometimes do this without mowing down all the grasses and flowers; and gardens can be designed in a very butterfly-friendly way. But the expressions ‘agriculture’, ‘landscape and garden care’ or even ‘nature conservation’, when referring to organizations and government works, are correct for the typical circumstances, since certain consequences emanate from them, and this book is generally concerned with these. For this reason, the impact of my statements will also depend on the spirit in which this book is read: I wrote it from a sense of responsibility that I feel we owe to future generations. Many people, a great many people, have been commenting on industrial agriculture for several decades, but they are still too few to achieve the political pressure that would be required to bring about a change for the better.

Part IThe Biodiversity of Lepidoptera

A Review of 50 Years of Butterfly and Moth Research

My records prevent me from creating rose-tinted memories of past conditions. I started keeping records on nature on 15 December 1958, and I therefore know, for example, that we did not have a ‘white Christmas’ in the Lower Bavarian Inn Valley 60 years ago, but it was, instead, two degrees above zero with light rain. On 2 January 1959, I noted that, outside on the River Inn, on the completely ice-free reservoir, I counted the following numbers of water birds: 800 mallards, 50 tufted ducks, 69 bean geese and 200 coots. Most of the numbers were rounded up, since I was not able to produce more accurate figures using my small binoculars from where I stood, half a kilometre away. I was not given a relatively powerful telescope until a few years later. As I pulled out and glanced through my old records in the course of preparing this book, I also came across a page with four butterflies that I had drawn myself. Astonished, I looked at it and read what I had written about the pictures ‘drawn from my collection’. Next to a swallowtail and a pair of Adonis blues, Polyommatus bellargus, I had drawn a large and striking black and white butterfly, a great banded grayling, and labelled it with the scientific name that was customary at the time, Satyrus circe. This discovery surprised me, since the beautiful ‘Circe’ that flies in such an elegant manner has long vanished from my region. It is largely extinct in Southern Bavaria, just like numerous other species of butterfly that I knew and observed in my youth.

Some of the species that were considered ordinary in those days do still exist, but they have, in the meantime, become rare or very rare. I also found a fitting example of this in my records. A note dated 12 September 1962 contained an observation that would be considered remarkable today. An almost palm-sized moth flew into the local train when we stopped at a station on our early morning journey to school and landed on the red shirt of my classmate. It was a red underwing, Catocala nupta (see Photo 1). When it is resting, the grey-brown, washed bark-coloured forewings of this large noctuid moth cover the bright crimson hindwings that are bordered with an angled black strip, just inside the outer margin. Not yet aware that moths – like all insects – cannot see the colour red, I wrote: ‘The red underwing was thus attracted by the red colour of the shirt.’ In fact, the red shirt would actually have seemed dark to the moth. To its vision in the so-called ‘grey-scale’, it may well have corresponded to a dark tree bark and the grey scales of its forewings. In the wild, the spot would have been suitable as a resting place during the day for this noctuid moth, which is active at twilight. One may therefore assume that red underwings were so common 50 years ago that one of them got lost in a train, presumably startled from its resting place in the station.

If this type of note from my schooldays was a mere anecdote, then these records would offer nothing further. Indeed, one retains what seems unusual, while the ordinary goes unnoticed. And yet, interesting points can be gleaned from unsystematic memos. I can find plenty of examples in my diaries. For example, the nine-spotted moth (or yellow belted burnet), Syntomis phegea, which has long since vanished from the area, sighted on 1 August 1960, or the caterpillar of the wood tiger, Parasemia plantaginis, recorded on 28 July 1960. The latter is only seen very rarely now. However, all of these and the many other records only show that there used to be Lepidoptera* species that no longer exist there. The true scope of the decline in butterflies and moths and other insects cannot be deduced from the disappearance of individual species. It is quite possible that other species that were not there earlier have appeared during this period. Nature is dynamic: changes can and will always occur. My initial claim that we have lost 80 per cent of the butterflies in the last 50 years refers to their overall frequency and requires much more concrete evidence.

I have already achieved that with birds: my counts of the water birds on the reservoirs of the lower River Inn, which I carried out every two to three days for six years, resulted in my first specialist ornithological publication in 1966. However, a quantitative survey of butterflies and moths was a very different challenge from counting birds that were resting on the banks or swimming on the water. My attempts gradually took form during my zoology studies at the University of Munich. A scientific approach was required for my doctoral thesis on aquatic moths, so I quickly familiarized myself with the five different species of moth that make up the Crambidae family and learnt how to reliably distinguish them by recognizing their flight patterns in the field.

However, given their number, moth and butterfly species require far greater knowledge if one wants to record all of them. The training is far more difficult and time-consuming than getting to know bird life. In southeast Bavaria alone, there are more than 1,100 species of butterfly and moth; for the whole of Bavaria, 3,243 have been reported (as of 2016). Many of these are very small and can only be identified with the help of specialist literature. For birds, there were already very good identification guides in the 1960s, which were not prohibitively expensive. Consequently, my initial engagement was with the bird world rather than with the butterflies. The reason was proximity, in the literal sense of the word: the reservoirs and riparian woods along the lower River Inn, which I could reach on foot or by bicycle, are a bird paradise. They are among the wetlands with the largest numbers of species in inland central Europe. When I started my zoology studies in Munich in 1965, I had already gained professional recognition as an ornithologist, thanks to my native surroundings, and I was familiar with various methods that are employed in field research.

Insects fly towards UV light

During my studies, I became familiar with a method that is more suitable than any other to establishing the abundance of moths. It consists of attracting species that are active at night using UV light. This is no longer done with large mercury-vapour lamps of 1,000 watts, which are used to light up white sheets that have been stretched behind them, as was common practice in the past and as I have attempted myself, but instead by means of an ingenious construction using UV neon tubes of only 15 watts. The moths and other insects are drawn in by this UV light. When they approach, they enter a funnel under the light tubes, leading to a large sack, in which the insects land. In order to offer them a place to hide until the following morning, empty egg cartons or similar are placed in the sack. This collection method does not harm the moths in any way. In the sack they quickly settle down, since the stimulus of the light has been removed. Together with the other insects, the moths are counted the following morning, and identified species by species, to the extent that their species identification is possible. At that point, all the insects are released immediately. In this manner, readily analysable and statistically useable results are achieved, which can be compared, depending on the problem in question, with a similar assembly of the apparatus in another location. This method can even be used to establish frequency and species composition of moths in quite different habitats. This is exactly what I did, starting from 1969. Dr Hermann Petersen perfected the method. I am greatly indebted both to him, and also to Elsbeth Werner for allowing me to use her pesticide-free farm for research.

Unfortunately, this type of light attraction does not work with butterflies. In order to establish changes in frequency for them in a comparable manner, I started to count them in the 1970s, along specific, fixed routes that would not be changed over the years. For example, along forest tracks or dirt tracks across fields, or along embankments already specified as transects. With their signs indicating river kilometres, placed at intervals of exactly 200 metres, these riverside routes are perfectly suited to such transect counts. In the 1980s, I primarily used the findings that I had obtained in this way for my lectures on ecology and nature conservation at the Technical University of Munich and on ecological biogeography at the University of Munich. Over the years, it became clear that the light traps and the route counts (or ‘transects’) yielded fewer and fewer butterflies. As for the ‘by-catch’, as I referred to the other insects that flew into my lights, even the cockchafers disappeared, despite previously having been so numerous. On more than one occasion, their mass flight to the UV light caused the sack to become detached from the funnel and fall to the ground, since up to 1,000 cockchafers had crept in there in the gloaming. Since there were often hardly any moths in the cockchafer season at the beginning of May, such a mishap did not compromise the annual totals. But the rather sudden decrease in the cockchafers perplexed me. This was the first signal that my investigations were providing important data about the changes to nature. Yet in the 1980s, I still had no inkling of how sharply downhill things would go for the moths and the other insects, nor that my findings would result in an eco-nutritional basis for the decline of the birds in the meadows and the fields.

Urban Lepidoptera: more common than expected

In the early 1980s, I also started to research butterfly and moth frequency in the city. Munich, the place where I had been a scientist at the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology (ZSM), offered ideal conditions for this. There were enough suitable locations from the centre to the city margins to provide a kind of cross-section of the occurrence and frequency of nocturnal insects. Moreover, the large collections present in this research museum, together with the assistance of my specialist colleagues, stood at my disposal during my endeavours to identify precisely all the insects. The fact that I would need their help became evident as soon as I started work on my first findings. They were so much more species-rich than expected that I could never have coped on my own. Furthermore, the catches turned out to be extraordinarily rich in terms of quantity, too. The widely held idea that there would only be a pitiful fraction of the species diversity found in the countryside was not only called into question by my findings, but immediately exposed as mere prejudice.

Over the years and decades, the extensive research results that I shall report in this book thus came into being. They represent the results of half a century of quantitative entomology.

Over the past half-century, nature has changed to an extent and at a speed that are simply unprecedented in such a short period. The findings are staggering and the prospects that they imply are exceptionally grim. This is because we cannot expect the main agent of this loss of species diversity – agriculture – to undergo any substantial change. Anyone who delves into the ‘agricultural problem’ in any depth will find that it has less to do with the farmers themselves than with agricultural politics. The billions of subsidies they have received over the last 50 years have resulted in a highly competitive displacement of the small-scale farms by the large ones. Traditional farmers more or less disappeared, until only a tenth of their former numbers now remain, and yet the victor in this situation, international agrobusiness – in particular, the producers of crop protection products – managed to keep a low public profile, while the decline of insects and birds proceeded in shocking parallel to the death of small-scale farm-based agriculture.

The much-maligned city life has long since become better than life in the country, where the slurry stinks to high heaven and poison is used in unprecedented quantities, and where the birds have been silenced and the groundwater is no longer fit to drink. How can things go on like this? Is it not possible to curb the spirits we once called upon in good faith to lighten the work of farmers and improve their lives? Can we even imagine a ‘butterfly effect’ that might lead to a reversal in the state of industrialized agriculture? Although it may surprise you, my outlook at the end of this book is cautiously optimistic. And yet perhaps this hesitantly expressed optimism is nothing but a dream, for future generations won’t appreciate what they haven’t come to know or experience themselves: the biodiversity of nature and our moths and butterflies.

Death’s head hawk-moth: a guest that can barely live with us anymore

Right now, species that could have had a lasting impact on our children, if only they had got to know them, are disappearing. I am thinking of the great wonder that seized me one evening in early October, when a death’s head hawk-moth emerged from its pupa in a glass on my windowsill (see Photo 2). I had found it during the potato harvest. In the early 1960s, the potato fields in Lower Bavaria were predominantly harvested in the old-fashioned way. A horse pulled a plough with its share set at such an angle that, with the correct spacing, it created a deep furrow on one side, while a line of earth about two hand-widths higher than required was tipped over with the potato haulms. Some potatoes would thus escape harvest. We would look for these and then find others that were still encased in earth, which we would grub out by hand. In our Lower Bavarian dialect, we called this ‘Kartoffelklauben’ (‘potato grubbing’). The caterpillars of the death’s head hawk-moth, however, also now feed on potato plants in summer, since they are adapted to eating plants of the nightshade (Solanaceae) family. The potato plant, which originally came from South America, belongs to this poisonous plant family.

The distant origins of the death’s head hawk-moth are not a disadvantage; they actually work in its favour. This is because there is nowhere in the wild where the females of these massive moths will find any nightshade plants in such abundance and so conveniently grown, with open ground around the bushes, as in a potato field. Accordingly, soon after its large-scale introduction into Europe in the early seventeenth century, the American potato plant became a preferred alternative for this large African hawk-moth. We can assume that, prior to this, it flew here from the edge of tropical Africa only seldom, due to the lack of suitable forage plants. The bittersweet nightshade, Solanum dulcamara, did not offer much nutrition and grows so sparsely that even today the caterpillar of the death’s head hawk-moth is rarely found on it.

When these caterpillars are fully grown, they dig an elongated hollow slightly below the surface of the ground, in which they pupate. After several weeks of pupation, the mature moths emerge, and must try to fly south, across the Alps. They will not survive the winter to the north of them. My specimen was just such a fully grown caterpillar. I had housed him in a clean jam jar on a bed of garden soil and loosely covered him. From time to time I would spray the soil a little, so that the pupa would not dry out. With success: the newly emerged death’s head hawk-moth, whose wings were not yet fully unfurled, not quite covering the yellow and black-ringed plump abdomen, appeared massive to me. More so, when I let it crawl onto my index finger so that I could place it on the curtains. This way of holding it would allow it to fully stretch out its wings, so that they could become fit for flying. My goal was, after all, to release it at dusk, so that it could return to Africa. The mere thought that this plan might be successful and that I might contribute to it excited me tremendously.

However, the pale-yellow design on the back of its thorax that was supposed to remind me of a skull made little impression on me. No matter which way I looked, it did not resemble a skull at all. Perhaps I simply lacked the imagination to conjure one up (see Photo 3). Even now, while I write this, I find it hard to imagine that men in earlier times could have come up with such an odd idea. But those who can see a liver in the leaves of a liverwort, just because it is made up of three ‘lobes’ (not remotely resembling a liver) and can conclude from this that it must be good for liver trouble, will surely manage to make out a mini-skull in the back markings of this hawk-moth.

I am no longer certain what was going through my head at the time, but something happened that awakened the biologist in me once and for all. Our cat, which had been lying on the sofa and pretending to be fast asleep, in the way that cats do, approached and stretched its nose up to the death’s head hawk-moth on the curtains. The moment one of its whiskers touched the moth, the yellow and black-ringed abdomen flicked up between the wings and the moth let out a shrill squeak. The cat recoiled in shock, fell off the edge of the sofa, and took cover underneath it.

The combined effect of the wasp- or hornet-like markings and the squeaking sound, which extends to the ultrasound range, and which may thus be partially inaudible to the human ear, was an object lesson for me: no book, no account of such a procedure, could have explained in a more striking way what ‘aposematic colouring’ means and how it works. I was particularly affected, since I had found it so easy to coax the hawk-moth onto my fingertip and to place it on the curtains. Years later, whenever I stroked a bumblebee, coaxing it to produce a quiet humming, I would think back to this experience. This death’s head hawk-moth, of which there would be dozens more in my life (until the potato harvest was mechanized and no more pupae were to be found or no specimen was able to survive the rough handling of the harvesting machine) – this moth that emerged under my care – touched me (see Photo 4).

*

In other words, butterflies and moths. ‘Lepidoptera’ is an order of insects that includes both. [Tr.]