2,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Qasim Idrees

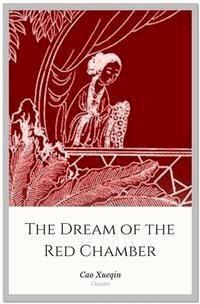

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Dream of the Red Chamber is one of the four Chinese classics. The novel is semi-autobiographical and it gives an incredibly detailed insight into 18th-century life in China, particularly that of the aristocracy. The plot is grand in scale, peopled with a complex array of characters.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

The Dream of the Red Chamber

Cao Xueqin

Translated By H. Bencraft Joly

.

THE DREAM OF THE RED CHAMBER.

CHAPTER I.

Chen Shih-yin, in a vision, apprehends perception and spirituality.

Chia Yü-ts'un, in the (windy and dusty) world, cherishes fond thoughts

of a beautiful maiden.

This is the opening section; this the first chapter. Subsequent to the visions of a dream which he had, on some previous occasion, experienced, the writer personally relates, he designedly concealed the true circumstances, and borrowed the attributes of perception and spirituality to relate this story of the Record of the Stone. With this purpose, he made use of such designations as Chen Shih-yin (truth under the garb of fiction) and the like. What are, however, the events recorded in this work? Who are the dramatis personae?

Wearied with the drudgery experienced of late in the world, the author speaking for himself, goes on to explain, with the lack of success which attended every single concern, I suddenly bethought myself of the womankind of past ages. Passing one by one under a minute scrutiny, I felt that in action and in lore, one and all were far above me; that in spite of the majesty of my manliness, I could not, in point of fact, compare with these characters of the gentle sex. And my shame forsooth then knew no bounds; while regret, on the other hand, was of no avail, as there was not even a remote possibility of a day of remedy.

On this very day it was that I became desirous to compile, in a connected form, for publication throughout the world, with a view to (universal) information, how that I bear inexorable and manifold retribution; inasmuch as what time, by the sustenance of the benevolence of Heaven, and the virtue of my ancestors, my apparel was rich and fine, and as what days my fare was savory and sumptuous, I disregarded the bounty of education and nurture of father and mother, and paid no heed to the virtue of precept and injunction of teachers and friends, with the result that I incurred the punishment, of failure recently in the least trifle, and the reckless waste of half my lifetime. There have been meanwhile, generation after generation, those in the inner chambers, the whole mass of whom could not, on any account, be, through my influence, allowed to fall into extinction, in order that I, unfilial as I have been, may have the means to screen my own shortcomings.

Hence it is that the thatched shed, with bamboo mat windows, the bed of tow and the stove of brick, which are at present my share, are not sufficient to deter me from carrying out the fixed purpose of my mind. And could I, furthermore, confront the morning breeze, the evening moon, the willows by the steps and the flowers in the courtyard, methinks these would moisten to a greater degree my mortal pen with ink; but though I lack culture and erudition, what harm is there, however, in employing fiction and unrecondite language to give utterance to the merits of these characters? And were I also able to induce the inmates of the inner chamber to understand and diffuse them, could I besides break the weariness of even so much as a single moment, or could I open the eyes of my contemporaries, will it not forsooth prove a boon?

This consideration has led to the usage of such names as Chia Yü-ts'un and other similar appellations.

More than any in these pages have been employed such words as dreams and visions; but these dreams constitute the main argument of this work, and combine, furthermore, the design of giving a word of warning to my readers.

Reader, can you suggest whence the story begins?

The narration may border on the limits of incoherency and triviality, but it possesses considerable zest. But to begin.

The Empress Nü Wo, (the goddess of works,) in fashioning blocks of stones, for the repair of the heavens, prepared, at the Ta Huang Hills and Wu Ch'i cave, 36,501 blocks of rough stone, each twelve chang in height, and twenty-four chang square. Of these stones, the Empress Wo only used 36,500; so that one single block remained over and above, without being turned to any account. This was cast down the Ch'ing Keng peak. This stone, strange to say, after having undergone a process of refinement, attained a nature of efficiency, and could, by its innate powers, set itself into motion and was able to expand and to contract.

When it became aware that the whole number of blocks had been made use of to repair the heavens, that it alone had been destitute of the necessary properties and had been unfit to attain selection, it forthwith felt within itself vexation and shame, and day and night, it gave way to anguish and sorrow.

One day, while it lamented its lot, it suddenly caught sight, at a great distance, of a Buddhist bonze and of a Taoist priest coming towards that direction. Their appearance was uncommon, their easy manner remarkable. When they drew near this Ch'ing Keng peak, they sat on the ground to rest, and began to converse. But on noticing the block newly-polished and brilliantly clear, which had moreover contracted in dimensions, and become no larger than the pendant of a fan, they were greatly filled with admiration. The Buddhist priest picked it up, and laid it in the palm of his hand.

"Your appearance," he said laughingly, "may well declare you to be a supernatural object, but as you lack any inherent quality it is necessary to inscribe a few characters on you, so that every one who shall see you may at once recognise you to be a remarkable thing. And subsequently, when you will be taken into a country where honour and affluence will reign, into a family cultured in mind and of official status, in a land where flowers and trees shall flourish with luxuriance, in a town of refinement, renown and glory; when you once will have been there…"

The stone listened with intense delight.

"What characters may I ask," it consequently inquired, "will you inscribe? and what place will I be taken to? pray, pray explain to me in lucid terms." "You mustn't be inquisitive," the bonze replied, with a smile, "in days to come you'll certainly understand everything." Having concluded these words, he forthwith put the stone in his sleeve, and proceeded leisurely on his journey, in company with the Taoist priest. Whither, however, he took the stone, is not divulged. Nor can it be known how many centuries and ages elapsed, before a Taoist priest, K'ung K'ung by name, passed, during his researches after the eternal reason and his quest after immortality, by these Ta Huang Hills, Wu Ch'i cave and Ch'ing Keng Peak. Suddenly perceiving a large block of stone, on the surface of which the traces of characters giving, in a connected form, the various incidents of its fate, could be clearly deciphered, K'ung K'ung examined them from first to last. They, in fact, explained how that this block of worthless stone had originally been devoid of the properties essential for the repairs to the heavens, how it would be transmuted into human form and introduced by Mang Mang the High Lord, and Miao Miao, the Divine, into the world of mortals, and how it would be led over the other bank (across the San Sara). On the surface, the record of the spot where it would fall, the place of its birth, as well as various family trifles and trivial love affairs of young ladies, verses, odes, speeches and enigmas was still complete; but the name of the dynasty and the year of the reign were obliterated, and could not be ascertained.

On the obverse, were also the following enigmatical verses:

Lacking in virtues meet the azure skies to mend,

In vain the mortal world full many a year I wend,

Of a former and after life these facts that be,

Who will for a tradition strange record for me?

K'ung K'ung, the Taoist, having pondered over these lines for a while, became aware that this stone had a history of some kind.

"Brother stone," he forthwith said, addressing the stone, "the concerns of past days recorded on you possess, according to your own account, a considerable amount of interest, and have been for this reason inscribed, with the intent of soliciting generations to hand them down as remarkable occurrences. But in my own opinion, they lack, in the first place, any data by means of which to establish the name of the Emperor and the year of his reign; and, in the second place, these constitute no record of any excellent policy, adopted by any high worthies or high loyal statesmen, in the government of the state, or in the rule of public morals. The contents simply treat of a certain number of maidens, of exceptional character; either of their love affairs or infatuations, or of their small deserts or insignificant talents; and were I to transcribe the whole collection of them, they would, nevertheless, not be estimated as a book of any exceptional worth."