4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ch. Links Verlag

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

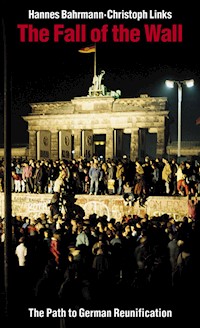

The dramatic events of Fall 1989 in East Germany changed global dynamics forever. These were the days of peaceful mass demonstrations, as East German citicens took the offensive in the struggle for freedom and democracy and the ruling party and its "security organs" gradually forfeited their power. After the collapse of the SED regime, a variety of citizens' movements and parties debated many possible ways of changing the political and social system in East Germany. But on March, 18, when the first free elections took place, voters gave a clear victory to the conservative "Alliance for Germany" and its program of rapid joinder with West Germany. The book documents the period of the so-called WENDE, from October 7, 1989 to March, 18, 1990, following developments day by day and reconstructing the road to German Reunification.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 202

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Hannes Bahrmann, Christoph Links

The Fall of the WallThe Path to German Reunification

Hannes BahrmannChristoph Links

The Fall of the Wall

The Path to German Reunification

Translated by Belinda Cooper

This book is a short version of the German edition of »Chronik der Wende«, published in 1999 by Christoph Links Verlag, Berlin.

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at www.dnb.de.

1st edition as e-book, April 2017

according to 1st print edition of September 1999

© Christoph Links Verlag

Schönhauser Allee 36, 10435 Berlin, Germany, Phone: +49 30 440232-0

www.christoph-links-verlag.de; [email protected]

Cover design: KahaneDesign, Berlin

Cover photo: Eberhard Klöppel

eISBN 978-3-86284-394-7

Table of Contents

Introduction

October 1989

Saturday, October 7

Sunday, October 8

Monday, October 9

Tuesday, October 10

Wednesday, October 11

Thursday, October 12

Friday, October 13

Saturday, October 14

Sunday, October 15

Monday, October 16

Tuesday, October 17

Wednesday, October 18

Thursday, October 19

Friday, October 20

Saturday, October 21

Sunday, October 22

Monday, October 23

Tuesday, October 24

Wednesday, October 25

Thursday, October 26

Friday, October 27

Saturday, October 28

Sunday, October 29

Monday, October 30

Tuesday, October 31

November 1989

Wednesday, November 1

Thursday, November 2

Friday, November 3

Saturday, November 4

Sunday, November 5

Monday, November 6

Tuesday, November 7

Wednesday, November 8

Thursday, November 9

Friday, November 10

Saturday, November 11

Sunday, November 12

Monday, November 13

Tuesday, November 14

Wednesday, November 15

Thursday, November 16

Friday, November 17

Saturday, November 18

Sunday, November 19

Monday, November 20

Tuesday, November 21

Wednesday, November 22

Thursday, November 23

Friday, November 24

Saturday, November 25

Sunday, November 26

Monday, November 27

Tuesday, November 28

Wednesday, November 29

Thursday, November 30

December 1989

Friday, December 1

Saturday, December 2

Sunday, December 3

Monday, December 4

Tuesday, December 5

Wednesday, December 6

Thursday, December 7

Friday, December 8

Saturday, December 9

Sunday, December 10

Monday, December 11

Tuesday, December 12

Wednesday, December 13

Thursday, December 14

Friday, December 15

Saturday, December 16

Sunday, December 17

Monday, December 18

Tuesday, December 19

Wednesday, December 20

Thursday, December 21

Friday, December 22

Saturday, December 23

Christmas, December 24 – 26

Wednesday, December 27

Thursday, December 28

Friday, December 29

Saturday, December 30

Sunday, December 31

January 1990

Monday, January 1

Tuesday, January 2

Wednesday, January 3

Thursday, January 4

Friday, January 5

Saturday, January 6

Sunday, January 7

Monday, January 8

Tuesday, January 9

Wednesday, January 10

Thursday, January 11

Friday, January 12

Saturday, January 13

Sunday, January 14

Monday, January 15

Tuesday, January 16

Wednesday, January 17

Thursday, January 18

Friday, January 19

Saturday, January 20

Sunday, January 21

Monday, January 22

Tuesday, January 23

Wednesday, January 24

Thursday, January 25

Friday, January 26

Saturday, January 27

Sunday, January 28

Monday, January 29

Tuesday, January 30

Wednesday, January 31

February 1990

Thursday, February 1

Friday, February 2

Saturday, February 3

Sunday, February 4

Monday, February 5

Tuesday, February 6

Wednesday, February 7

Thursday, February 8

Friday, February 9

Saturday, February 10

Sunday, February 11

Monday, February 12

Tuesday, February 13

Wednesday, February 14

Thursday, February 15

Friday, February 16

Saturday, February 17

Sunday, February 18

Monday, February 19

Tuesday, February 20

Wednesday, February 21

Thursday, February 22

Friday, February 23

Saturday, February 24

Sunday, February 25

Monday, February 26

Tuesday, February 27

Wednesday, February 28

March 1990

Thursday, March 1

Friday, March 2

Saturday, March 3

Sunday, March 4

Monday, March 5

Tuesday, March 6

Wednesday, March 7

Thursday, March 8

Friday, March 9

Saturday, March 10

Sunday, March 11

Monday, March 12

Tuesday, March 13

Wednesday, March 14

Thursday, March 15

Friday, March 16

Saturday, March 17

Sunday, March 18

About the Authors

Introduction

The dramatic changes in East Germany in autumn of 1989 have been labeled many things in hindsight: awakening, radical reform, even revolution. But of all the scholarly definitions and literary descriptions, none has taken as firm a hold as the expression Wende – literally, a turn. It is not the most precise phrase, and its original meaning was quite different. It was first employed by Egon Krenz on October 18, 1989, following his election as the new Socialist Unity Party (SED) General Secretary, when he uncertainly addressed the public on East German television. In his view, the removal of Party leader and head of state Erich Honecker would initiate a »turn« in Party efforts to »retake the political and ideological offensive.« But the public interpreted the »turn« in its own way, taking the offensive itself. The rigged local elections of May 7, 1989 had been the last straw. At a time when rigid social conditions in the East Bloc had finally begun to relax, Gorbachev’s Soviet Union was starting to reform and opposition candidates were campaigning in Poland, East German citizens were exhorted to provide a »unanimous show of support for the candidates of the National Front« – that is, to give their unchallenged blessing to the single SED-dominated list of candidates. But now, for the first time, citizens’ groups and church organizations set out to observe the ballot counting, and they registered several more percentage points’ worth of crossed-out names – that is, »no« votes – than the official figures announced by Election Chairman Egon Krenz.

The disinterest in reforms on the part of SED leaders, reinforced by East Germany's official support for the violent suppression of the democratic movement in China in early June, led to a mass exodus of East Germans to West Germany, which was in any case viewed by many as an attractive alternative. By autumn, tens of thousands had reached the West through the Hungarian border with Austria or the West German embassies in Prague, Warsaw and Budapest. Despite this »voting with their feet,« the doddering SED leadership, completely oblivious to reality, prepared once again to celebrate itself, choosing for the purpose East Germany's fortieth anniversary on October 7, 1989.

But the celebration turned into its opposite, and would mark the beginning of the end. In Leipzig, Dresden and Berlin, protests of asyet unheard of magnitude took place and spread during the days that followed. In the process, they challenged the ruling party's right to continue acting in the name of the people. At the end of October, tens of thousands took to the streets shouting »We are the people« and demanding radical transformation of their society. They insisted that democratic freedoms had to become a permanent reality in Germany's east as well as its west, and they were no longer willing to be bought off with promises and a few concessions. The right to demonstrate, defiantly won in the streets, and the right to travel, which suddenly became the norm through the unexpected opening of the Wall on November 9, were followed by the rights of speech and assembly and the gradual disempowering of the ruling party and its »security organs.«

At no point did opposition groups make any attempt to take direct power. The majority were certain that government without their participation was no longer possible; they believed they needed only to push consistently for rapid, free elections. The continuing rallies, especially in the south of the country, were impressive proof of this. Thus, the second phase of restructuring was characterized above all by a debate over the modalities of the first free elections in the history of East Germany, a debate in which the West German parties would then set the tone. The clear vote on March 18, 1990 for the conservative »Alliance for Germany« and its program of rapid joinder with West Germany marked the end of the actual Wende. It was a true transfer of power, accomplished by peaceful means, and led to official unification on October 3, 1990.

Germany had never before experienced a similar successful popular uprising against an illegitimate ruler. Our aim has been to document this special process in all its facets.

Christoph Links/Hannes Bahrmann

Berlin, May 1999

October 1989

Saturday, October 7

Today East Germany turns 40. In East Berlin, the day begins with street cleaning: cleanup crews clear away the remains of last night's torchlight parade by the Free German Youth, at which a hundred thousand young people marched past Party leader and head of state Erich Honecker. At 10:00 a.m. a large military parade begins on Karl Marx Allee, despite objections from the Western allies. In the afternoon, all districts in the city hold street fairs. But little enthusiasm is evident; the country is experiencing an unprecedented degree of tension. Since September 10, thousands of people, many of them young, have been abandoning the country for the West, fleeing through Hungary or seeking refuge in West German consulates in Prague and Warsaw. The reasons are many: dissatisfaction with restrictions on travel, limited rights to free expression, lack of political freedom, the hypocrisy of the media, the shortage of consumer goods in comparison with the West, the deterioration of cities and factories. All this has caused disillusionment – and determination.

Around 5 p.m., several hundred young people gather on Alexanderplatz in East Berlin »to whistle at the elections*.« They protest the manipulation of the most recent local elections with a concert of whistles, then debate with onlookers and begin to chant slogans. In contrast to earlier rallies, with their choruses of »We want out!«, this time the defiant cry is »We're staying here!« – meaning that the problems that have accumulated cannot simply be pushed aside, but must be dealt with in the country itself.

The protesters move in the direction of the Palace of the Republic, where top state and Party officials are celebrating the country's anniversary with invited guests, including Soviet reformer Mikhail Gorbachev; the crowd, now grown to two or three thousand, chants »Gorbi, help us« and »We are the people!« But they are pushed back by police, and turn north toward the district of Prenzlauer Berg. There, in the Gethsemane Church (Gethsemanekirche), a vigil for political prisoners has been going on since last week. When the demonstrators pass the offices of ADN, the state news agency, they yell »Liars! Liars!« and »Press freedom – freedom of opinion!« Police cars begin to arrive on the scene, and officers block off the side streets. There are scuffles and arrests, with police using their clubs. »No violence!« cries the crowd, surging forward. Fifteen hundred people finally reach the Gethsemane Church on Schönhauser Allee, as special units of the police and security officers hermetically seal the area. Toward midnight comes the order to attack; the same occurs in Leipzig, Dresden, Plauen, Jena, Magdeburg, Ilmenau, Arnstadt, Karl-Marx-Stadt and Potsdam, where other political demonstrations on this holiday are also broken up forcibly. The same evening, a Social Democratic Party (SDP) for East Germany is founded in the small town of Schwante, north of Berlin. The party demands an ecologically-oriented social market economy with democratic control of economic power, free labor unions with the right to strike, the right to travel and emigrate, and recognition of two German states.

Sunday, October 8

At Sunday mass, religious leaders call for calm and nonviolence. The dissident movement »New Forum,« founded a few weeks ago, distributes typed flyers exhorting, »Force is not a method of political debate. Do not let yourselves be provoked!«

More violent confrontations take place in Dresden. Mayor Wolfgang Berghofer attempts to begin a dialogue, meeting with a spontaneously formed citizens’ committee called the »Group of Twenty«; but the police, following orders from the top, again employ force. Among those arrested is Michael Dulig, who describes what happened:

»We had to stand with our faces to the wall, legs spread and hands leaning diagonally against the wall. It's called the flyer's position. In this position, we were subjected to a body search and had our IDs and belts taken from us. An officer in battle dress, probably the operation chief, informed us that we were in a militarily-secured building. If we attempted to escape, weapons would be used. Around 10:30 p.m., correction officer trainees in battle dress stormed the garage, yelling. They beat us in the back and neck with clubs, grabbed those standing farthest back and brutally shoved them into the position required. They beat them with clubs or kicked them between the legs until they had spread their legs wide enough. Those who didn't react immediately or who complained were shouted at, brutally dragged out of the garage, and thrown against the gates …«

On the evening of October 8, violent scenes also play out around Gethsemane Church in East Berlin. Following a prayer service, police units surround the crowd leaving the church and demand that all 3,000 pass individually through a checkpoint. But the group stays together and, lit candles in hand, begins a sitdown strike. At that, the police forcibly clear the area. The cries of the victims mingle with the midnight tocsin from the church. Violence escalates uncontrollably.

Monday, October 9

In Leipzig, the situation takes a dangerous turn before the weekly Monday demonstration by opposition groups. It becomes known that medical personnel have been called in for night duty, entire hospital wards cleared and additional blood reserves prepared. People expect the worst this evening. The Tienanmen Square syndrome is in the air; it is no longer possible to rule out a violent response on the Chinese model, with many injured and perhaps killed. In this situation, prominent artists, including the Chief Conductor of the Gewandhaus Orchestra, Kurt Masur, a pastor and three district Socialist Unity Party [SED] Secretaries meet to begin an initiative for de-escalation. In the afternoon, their joint statement is read out on local radio: »We are distressed by the developments in our city and are seeking a solution. We all need a free exchange of opinions about how to develop socialism in our country … We urge you to remain calm so that a peaceful dialogue will be possible.«

In the evening, Leipzig witnesses the largest protest demonstration in East Germany since the uprising of June 17, 1953: seventy thousand people march through the city center. The police no longer stand a chance, and they retreat in face of this overwhelming mass. Again and again, the decisive cry echoes: »We are the people!« It tells those in power that they have forfeited the right to act in the name of the people.

Tuesday, October 10

Many breath a sigh of relief; in most cities, the night has passed peacefully. Only the industrial city of Halle has again seen brutal police attacks on demonstrators. In East Berlin, though, security forces were withdrawn, so that a quiet rally around the Gesthemane Church breaks up on its own in the early morning hours. Throughout the night, candles burn in many windows in the neighborhood as a token of solidarity.

Behind the scenes, the power struggle escalates. The SED Politburo, the actual center of power in the country, meets today in plenary session. But there is no clear majority for reform as yet.

While the political leadership cannot agree and remains largely paralyzed, the demands of various grass-roots groups gain in force and variety. Along with New Forum's call for a dialogue on democratizing society, the platform of the newly-founded SDP for reforming East Germany and the demands of the citizens' group Democracy Now (DJ)are distributed in churches and factories. The latter declares, »We want the socialist revolution, which never got past nationalization, to be carried on and given a perspective for the future. Instead of a custodial, Party-dominated state that has raised itself to the status of principal and schoolmaster over the people, with no social mandate, we want a state based on a fundamental social consensus that is accountable to society and thus becomes a public concern of mature citizens.«

Wednesday, October 11

The Politburo continues to meet, but has reached no decisions. In a final declaration, it again denies the need to democratize society and labels the past days' demonstrators »irresponsible disturbers of peace and order.« In a BBC interview, Markus Wolf, retired general of the Ministry for State Security, former espionage chief and advocate of the Gorbachev line in the East German leadership, says the changes in East Germany are too little and too slow, and adds that this is contributing to a sense of hopelessness among some segments of the population. At the orders of the SED leadership, all broadcasts by the West Berlin radio station Hundert, 6 in which the words East Germany appear are disrupted by heavy static. Obviously lacking arguments and wishing to conceal their own defensive political posture, these leaders fall back on Cold War methods.

Thursday, October 12

In an attempt to stop the stream of emigrants to West German consulates in Prague, or from Hungary to Austria, the Ministry of the Interior announces that only retirees and invalids may apply to travel to Czechoslovakia for the present. These are the same people who are allowed to travel to the West under current law. Since visa-free travel to Poland was suspended on October 30, 1980, Czechoslovakia has been the only country to which East Germans could travel without permission and using only their identity cards. Nine million East Germans visited this neighboring country in 1988 alone. Travel documents are necessary for all other socialist countries, and they require application to the police weeks in advance. Since 1980, travel to Poland has also required an invitation.

Grass-roots demands for change become louder. For example, New Forum demands (1) official recognition of all grass-roots groups, parties and initiatives working for democratization of society; (2) access to the mass media; (3) press freedom and the elimination of censorship; (4) freedom of assembly and the right to demonstrate.

Friday, October 13

In the morning, the SED leadership, represented by Erich Honecker and his two closest advisors, Central Committee Secretaries Günter Mittag and Joachim Herrmann, meets in East Berlin with the chairmen of the four parties that, together with the SED, officially comprise the parliament's »democratic bloc.« Honecker proposes that socialism in East Germany be »constantly improved by thoroughgoing change and reform,« but at the same time makes it clear that the current model of sole SED leadership will be retained.

In the afternoon, the Prosecutor General’s office announces that, with the exception of eleven people under investigation for acts of violence, all arrested demonstrators have been released. Prominent East Berlin lawyer Wolfgang Vogel, a confidant of Honecker who has dealt with difficult inter-German humanitarian cases, calls for the release of all East Germans arrested for attempting to leave the country and in connection with the recent demonstrations.

Saturday, October 14

In the morning, the 50,000th East Germany refugee since the opening of the Hungarian border arrives in West Germany. The radio station Sender Freies Berlin (Radio Free Berlin) broadcasts a portrait of a couple who fled from East to West Berlin via Hungary. The young woman is filmed looking for a job. Already, of the 84,000 unemployed in the western part of the city, every tenth person is an East German immigrant.

Some 120 members of New Forum, whose founding statement has now been signed by over 25,000 people, meet in East Berlin for their first coordination meeting. There, it is announced that the mayor of Karl-Marx-Stadt has offered to enter into a dialogue with representatives of New Forum. Official contact has also taken place in Leipzig and Potsdam. However, representatives in Halle have encountered difficulties, with some arrested by the police in recent days. The members foresee the movement spreading according to a grass-roots principle. They plan to form a coordinating committee and elect a speakers' council made up of representatives from the regional centers.

Unlike the SDP, which emerged from the beginning with an almost complete structure and platform, the citizens' movement Democracy Now, with 1,000 members at this point, takes a similar approach to that of New Forum. »We propose that you seek connections with like-minded groups in your neighborhood. Organize meetings in districts and counties. Elect spokeswomen and spokesmen. Send representatives to national events,« says one of their flyers.

Sunday, October 15

In Berlin, the ongoing vigils and prayer services are showing signs of success: the demonstrators arrested on October 7 and 8 are freed. But the vigils continue. Participants demand an investigation of police abuses and punishment of those responsible.

The East Berlin initiative Democratic Awakening meets today. The group formed over the summer out of church-based groups; its best-known member so far is Rainer Eppelmann, pastor of Berlin's Samaritan Church (Samariterkirche). In an open letter to East Berlin Mayor Erhard Krack, the group calls for creation of an independent investigatory commission to look into the rights violations on October 7 and 8. Violence and intimidation, they say, cannot be suitable conditions for democratic dialogue.

In the evening, a »Concert against Violence« takes place in East Berlin's Redeemer Church (Erlöserkirche). Singers and writers call for fundamental reforms. Enormous applause breaks out when writer and songwriter Gerhard Schöne announces that, of the 20,000 marks he received as part of the East German National Prize he was awarded on October 7, he is giving half to a church development aid group and half to the arrestees.

Monday, October 16

Harry Tisch, head of the FDGB, the unified official trade union, admits after discussions with workers, that »the mood among workers has changed.« Instead of agreement with SED policies, he is treated to harsh criticism. Nevertheless, he clings to the old line. In his opinion, East Germany needs no new democratic fora, as it already has all necessary structures. To a journalist's question whether reports of power struggles within the SED Politburo are true, Tisch, who has belonged to the body since 1975, responds, »Numerous Western media are specialists in reading coffee grounds. They spread lies, falsify information, manipulate half-truths. They blend fact and fantasy to fit their anti-Communist concept, now more than ever.« He has nothing else to say about the current situation.

Outside the country, the situation is viewed more soberly and thus more realistically. Vyacheslav Dachichev, one of Mikhail Gorbachev's foreign policy advisors, says in a talk with the Frankfurter Rundschau newspaper, »The mood among the East German population reflects conditions in the country. If the leadership does not notice this, it can lead to very dangerous discrepancies between the thinking of the government and of the public … East Germany's entire economic and political system is based on the old Stalinist concept of administrative socialism.«

In the evening, more people take to the streets than ever before: 120,000 in Leipzig alone, 10,000 each in Dresden and Magdeburg, 5,000 in Halle and 3,000 in East Berlin. Their demands are similar: recognition of New Forum, free elections, freedom of the press and of opinion, elimination of the visa requirement for travel to Czechoslovakia and complete freedom to travel.

Tuesday, October 17

In East Berlin, more than 4,000 students at Humboldt University discuss overdue reforms. Their demands include independent student representatives, an uncensored student newspaper, and unrestricted access to all library materials and to photocopiers.

Workers at the Wilhelm Pieck Appliance and Regulator Factory in Teltow, south of Berlin, leave the FDGB to form an independent enterprise group called Reform. They call for the creation of independent trade unions.

Wednesday, October 18

In the morning, Manfred von Ardenne, a well-known Dresden scientist, says he has the impression that the SED leadership has not yet grasped the seriousness of the situation and complains that there have been no »significant deeds and changes.« He is articulating the feeling of a majority of the population.

In the afternoon comes sensational news: Erich Honecker has resigned. At his suggestion, Egon Krenz is elected as the new General Secretary of the SED Central Committee. The announcement about the Central Committee meeting continues with the news that Politburo members and Central Committee Secretaries Günter Mittag (economy) and Joachim Herrmann (media) have been removed from their posts.