Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

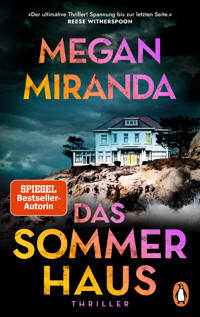

REESE'S BOOK CLUB x HELLO SUNSHINE AUGUST 2019 PICK! FROM THE BESTSELLING AUTHOR OF ALL THE MISSING GIRLS 'The perfect summer thriller ... twisty and tense, with a pace that made my heart race. An edge-of-your-seat, up-all-night read.' Riley Sager, author of The Last Time I Lied 'A riveting read!'Mary Kubica, author of The Good Girl 'Dizzying plot twists and multiple surprise endings are this author's stock in trade... And, oh boy, does she ever know how to write [them].' Marilyn Stasio, New York Times Book Review Never overstay your welcome... One year ago, Avery's best friend Sadie was found dead - dashed on the rocks the night of the infamous end-of-summer party. To Avery's disbelief, the police quickly rule Sadie's death a suicide. A year later new evidence surfaces that suggests Sadie was murdered. Evidence that places Avery under suspicion. Grief-stricken and ostracized, Avery must clear her name before she's branded a killer... 'Fast-paced and gripping.'People

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 439

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ALSO BY MEGAN MIRANDA

The Perfect Stranger

All the Missing Girls

First published in the United States in 2019 by Simon & Schuster, New York.

First published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2019 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Megan Miranda, 2019

The moral right of Megan Miranda to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 291 3

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 292 0

Printed in

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For Rachel

SUMMER

2017

The Plus-One Party

I almost went back for her. When she didn’t show. When she didn’t answer her phone. When she didn’t reply to my text.

But there were the drinks, and the cars blocking me in, and the responsibility—I was supposed to be keeping an eye on things. I was expected to keep the night running smoothly.

Anyway, she would laugh at me for coming back. Roll her eyes. Say, I already have one mother, Avery.

These are excuses, I know.

——

I HAD ARRIVED AT the overlook first.

The party was at the rental on the cul-de-sac this year, a three-bedroom house at the end of a long tree-lined road, barely enough room for two cars to maneuver at the same time. The Lomans had named it Blue Robin, for the pale blue clapboard siding and the way the squared roof looked like the top of a bird feeder. Though I thought it was more fitting for the way it was set back in the trees, a flash of color as you stepped to the side, something you couldn’t really see until you were already upon it.

It wasn’t the nicest location or the one with the best view—too far to see the ocean, just close enough to hear—but it was the farthest from the bed-and-breakfast down the road, and the patio was surrounded by tightly packed evergreens, so hopefully, no one would notice or complain.

The Lomans’ summer rentals all looked the same on the inside, anyway, so that sometimes I’d leave a walk-through completely disoriented: a porch swing in place of the stone steps; the ocean instead of the mountains. Each home had the same tiled floor, the same shade of granite, the same style of rustic-meets-upscale. And the walls throughout, decorated with scenes of Lit-tleport: the lighthouse, the white masts dancing in the harbor, the foam-crested waves colliding with the sea cliffs on either side. A drowned coast, it was called—fingers of land rising from the ocean, the rocky coastline trying to stand its ground against the surf, islands appearing and vanishing in the distance with the tide.

I got it, I did. Why the long weekend drives from the cities or the temporary relocation for the summer season; why the exclusivity of a place that seemed so small and unassuming. It was a town carved out of the untouched wild, mountains on one side, ocean on the other, accessible only by a single coastal road and patience. It existed through pure stubbornness, pushing back against nature from both sides.

Growing up here made you feel as if you were forged from this same character.

I emptied the box of leftover liquor from the main house onto the granite island, hid away the fragile decorations, turned on the pool lights. Then I poured myself a drink and sat on the back patio, listening to the sounds of the ocean. A chill of autumn wind moved through the trees, and I shivered, pulling my jacket tighter.

This annual party always teetered on the edge of something—one last fight against the turning of the season. Winter settled in the bones here, dark and endless. It was coming, just as soon as the visitors were leaving.

But first there would be this.

Another wave crashed in the distance. I closed my eyes, counting the seconds. Waiting.

We were here tonight to ring out the summer season, but it had already swept out to sea without our permission.

——

LUCIANA ARRIVED JUST AS the party was hitting its momentum. I didn’t see her come in, but she stood alone in the kitchen, unsure of herself. She stood out, tall and unmoving in the hub of activity, taking it all in. Her first Plus-One party. So different, I knew, from the parties she’d been attending all summer, her welcome to the world of Summers in Littleport, Maine.

I touched her elbow, still cold somehow. She flinched as she turned my way, then exhaled like she was glad to see me. “This is not exactly what I expected,” she said.

She was too done up for the occasion. Hair curled just so, tailored pants, heels. Like she was attending a brunch.

I smiled. “Is Sadie with you?” I looked around the room for the familiar dark blond hair parted down the middle, the thin braids woven from her temples and clipped together at the back, a child from another era. I stood on my toes, trying to tune in to the sound of her laughter.

Luce shook her head, the dark waves slipping over her shoulders. “No, I think she was still packing. Parker dropped me off. Said he wanted to leave the car at the bed-and-breakfast so we could get out easier after.” She gestured in the general direction of the Point Bed-and-Breakfast, a converted Victorian eight-bedroom home at the tip of the overlook, complete with multiple turrets and a widow’s walk. There, you could almost make out the entirety of Littleport—all the parts that mattered, anyway—from the harbor to the sandy strip of Breaker Beach, its bluffs jutting out into the sea, where the Lomans lived at the northern edge of town.

“He shouldn’t park there,” I said, phone already in my hand. So much for the owners of the B&B not noticing if people were going to start leaving cars in their lot.

Luce shrugged. Parker Loman did what Parker Loman wanted to do, never worrying about the repercussions.

I held the phone to my ear. I could barely hear the ringing over the music and cupped a hand over the other side.

Hi, you’ve reached Sadie Loman—

I pressed end, slid the phone back into my pocket, then handed Luce a red plastic cup. “Here,” I said. What I really wanted to say was, My God, take a breath, relax, but this was already exceeding the typical limits of my conversations with Luciana Suarez. She held the cup tentatively as I moved the half-empty bottles around, looking for the whiskey I knew she preferred. It was one thing I really liked about her.

After I poured, she frowned and said, “Thanks.”

“No problem.”

A full season together and she still didn’t know what to make of me, the woman living in the guesthouse beside her boyfriend’s summer home. Friend or foe. Ally or antagonist.

Then she seemed to decide on something, because she leaned a little closer, as if getting ready to share a secret. “I still don’t really get it.”

I grinned. “You’ll see.” She’d been questioning the Plus-One party since Parker and Sadie told her about it; told her they wouldn’t be leaving with their parents on Labor Day weekend but would be staying until the week after the end of the season for this. One last night for the people who stayed from Memorial Day to Labor Day, the weeks making up the summer season, plus one. Spilling over into the lives of the folks who lived here year-round.

Unlike the parties the Lomans had taken her to all summer, this party would have no caterers, no hostesses, no bartenders. In their place would be an assortment of leftovers from the visitors emptying the liquor cabinets, the fridges, the pantries. Nothing matched. Nothing had a place. It was a night of excess, a long goodbye, nine months to forget and to hope that others had, too.

The Plus-One party was both exclusive and not. There was no guest list. If you heard about it, you were in. The adults with real responsibilities had all gone back to their normal lives by now. The younger kids had returned to school, and their parents had left along with them. So this fell to the midgap. College age and up, before the responsibilities of life kept you back. Until things like this wore you thin.

Tonight circumstances leveled us out, and you couldn’t tell just from looking who was a resident and who was a visitor. We pretended that: Strip us down and we’re all the same.

Luce checked her fine gold watch twice in as many minutes, twisting it back and forth over the bone of her wrist each time. “God,” she said, “he’s taking forever.”

——

PARKER ARRIVED LAST, HIS gaze seeking us out easily from the doorway. All heads turned his way, as often happened when Parker Loman entered the room. It was the way he carried himself, an aloofness he’d perfected, designed to keep everyone on their toes.

“They’re going to notice the car,” I said when he joined us.

He leaned down and slipped an arm around Luce. “You worry too much, Avery.”

I did, but it was only because he’d never considered how he appeared to the other side—the residents who lived here, who both needed and resented people like him.

“Where’s Sadie?” I asked over the music.

“I thought she was getting a ride with you.” He shrugged, then looked somewhere over my shoulder. “She told me not to wait for her earlier. Guess that was Sadie-speak for not coming.”

I shook my head. Sadie hadn’t missed a Plus-One since the first one we’d attended together, the summer we were eighteen.

Earlier in the day, she’d thrown open the door to the guesthouse without knocking, called my name from the front room, then again even as she entered my bedroom, where I sat with the laptop open on the white comforter, in my pajama shorts and long-sleeve thermal with my hair in a bun on top of my head.

She was already dressed for the day, whereas I was catching up on my responsibilities for Grant Loman’s property management company, one thread of his massive real estate development firm. Sadie, wearing a blue slip dress and gold strappy sandals, had leaned on her hip so I could see the jut of her bone, and said, What do we think of this? The dress clung to every line and curve.

I’d reclined against my pillows, bent my knees, thinking she was going to stay. You know you’ll freeze, right? I’d said. The temperature had plummeted the last few evenings—a precursor to the abandoning, as the locals called it. In a week, the restaurants and shops along Harbor Drive would change hours, while the landscapers became school maintenance and bus drivers, and the kids who worked as waitresses and deckhands took off for the slopes in New Hampshire to work as ski instructors. The rest of us were accustomed to sucking the summer dry, as if stockpiling water before a drought.

Sadie had rolled her eyes. I already have one mother, she’d said, but she’d pieced through my closet and shrugged on a chocolate brown sweater, which had been hers anyway. It turned her outfit the perfect blend of dressy and casual. Effortless. She’d spun toward the door, her fingers restless in the ends of her hair, her energy spilling over.

What else could she have been getting ready for if not this?

Through the open patio doors, I noticed Connor sitting at the edge of the pool, his jeans rolled up and his bare feet dangling in the water, glowing blue from the light below. I almost walked up to him and asked if he’d seen her, but that was only because drinking opened up a sense of nostalgia in me. Even then, I thought better of it. He caught me staring, and I turned away. I hadn’t expected to see him here, was all.

I pulled out my phone, sent her a text: Where are you?

I was still watching the screen when I saw the dots indicating she was writing a response. Then they stopped, but no message came through.

I sent one more: ???

No response. I stared at the screen for another minute before slipping the phone away again, assuming she was on her way, despite Parker’s claim.

Someone in the kitchen was dancing. Parker tipped his head back and laughed. The magic was happening.

There was a hand on my back, and I closed my eyes, leaning in to it, becoming someone else.

It’s how these things go.

——

BY MIDNIGHT, EVERYTHING HAD turned fragmented and hazy, the room thick with heat and laughter despite the open patio doors. Parker caught my gaze over the crowd from just inside the patio exit, tipped his head slightly toward the front door. Warning me.

I followed his eyes. There were two police officers standing in the open doorway, the cold air sobering us as the gust funneled from the entrance out the back doors. Neither man had a hat on, as if they were trying to blend in. I already knew this would fall to me.

The house was in the Lomans’ name, but I was listed as the property manager. More important, I was the one expected to navigate the two worlds here, like I belonged to both, when really I was a member of neither.

I recognized the two men but not well enough to pull their names from memory. Without the summer visitors, Littleport had a population of just under three thousand. It was clear they recognized me, too. I’d spent the year between ages eighteen and nineteen in and out of trouble, and the officers were old enough to remember that time.

I didn’t wait to hear their complaint. “I’m sorry,” I said, making sure my voice was steady and firm. “I’ll make sure we keep the noise level down.” Already, I was gesturing to no one in particular to lower the volume.

But the officers didn’t acknowledge my apology. “We’re looking for Parker Loman,” the shorter of the two said, scanning the crowd. I turned toward Parker, who had already begun pushing through the crowd in our direction.

“Parker Loman?” the taller officer said when he was within earshot. Of course they knew it was him.

Parker nodded, his back straight. “What can I do for you gentlemen,” he said, becoming business Parker even as a piece of dark hair fell into his eyes; the sheen of sweat made his face glow brighter.

“We need to speak with you outside,” the taller man said, and Parker, ever the appeaser, knew the line to walk.

“Of course,” he said, not moving any closer. “Can you tell me what this is about first?” He also knew when to talk and when to demand a lawyer. He already had his phone in his hand.

“Your sister,” the officer said, and the shorter man’s gaze slipped to the side. “Sadie.” He gestured Parker closer, lowering his voice so I couldn’t make out what they were saying, but everything shifted. The way Parker was standing, his expression, the phone hanging limply at his side. I stepped closer, something fluttering in my chest. I caught the end of the exchange. “What was she wearing, last time you saw her?” the officer asked.

Parker narrowed his eyes. “I don’t . . .” He looked at the room behind him, seeming to expect that she’d slipped inside without either of us noticing.

I didn’t understand the question, but I knew the answer. “A blue dress,” I said. “Brown sweater. Gold sandals.”

The men in uniform shared a quick look, then stepped aside, allowing me into their group. “Any identifying marks?”

Parker pressed his eyes shut. “Wait,” he said, like he could redirect the conversation, alter the inevitable course of events to follow.

“Yes, she does, right?” Luce said. I hadn’t noticed her standing there; she was just beyond Parker’s shoulder. Her hair was pulled back and her makeup had started to run, faint circles under her eyes. Luce stepped forward, her gaze darting between Parker and me. She nodded, more sure of herself. “A tattoo,” she said. “Right here.” She pointed to the spot on her own body, just on the inside of her left hip bone. Her finger traced the shape of a figure eight turned on its side—the symbol of infinity.

The cop’s jaw tensed, and that was when the bottom fell away in a rush.

We had become temporarily unmoored, small boats in the ocean, and I sensed that seasick feeling I could never quite overcome out on the water at night, despite growing up so close to the coast. A disorienting darkness with no frame of reference.

The taller cop had a hand on Parker’s arm. “Your sister was found on Breaker Beach . . .”

The room buzzed, and Luce’s hands went to her mouth, but I still wasn’t sure what they were saying. What Sadie was doing on Breaker Beach. I pictured her dancing, barefoot. Skinny-dipping in the ice-cold water on a dare. Her face lit up from the glow of a bonfire we’d made from driftwood.

Behind us, half the party continued, but the noise was dropping. The music, cut.

“Call your parents,” the officer continued. “We need you to come down to the station.”

“No,” I said, “she’s . . .” Packing. Getting ready. On her way. The cop’s eyes widened, and he looked down at my hands. They were gripping the edge of his sleeve, my fingertips blanched white.

I released him, backed up a step, bumped into another body. The dots on my phone—she had been writing to me. The cops had to be wrong. I pulled out my phone to check. But my question marks to Sadie remained unacknowledged.

Parker pushed past the men, charging out the front door, disappearing around the back of the house, headed down the path toward the B&B. In the commotion, you couldn’t contain us. Luce and I sprinted after him through the trees, eventually catching up in the gravel parking lot, pushing into his car.

The only noise as we drove past the dark storefronts lining Harbor Drive was the periodic hitch in Luce’s breath. I leaned closer to the window when we reached the curve leading to Breaker Beach, the lights flashing ahead, the police cars blocking the entrance to the lot. But an officer stood guard behind the dunes, gesturing with a glowing stick for us to drive on by.

Parker didn’t even slow down. He took the car up the incline of Landing Lane to the house at the end of the street, standing dark behind the stone-edged drive.

Parker stopped the car and went straight inside—either to check for Sadie, also disbelieving, or to call his parents in privacy. Luce followed him slowly up the front steps, but she looked over her shoulder first, at me.

I stumbled around the corner of the house, my hand on the siding to steady myself, passing the black gate surrounding the pool, heading straight for the cliff path beyond. The path traced the edge of the bluffs until they ended abruptly at the northern tip of Breaker Beach. But there was a set of steps cut into the rock from there, leading down to the sand.

I wanted to see the beach for myself, to believe. See what the police were doing down below. See if Sadie was arguing with them. If we had misunderstood. Even though I knew better by then. This place, it took people from me. And I had grown complacent in forgetting that.

I could hear the crash of the waves colliding with the cliffs to my left, could picture the way the force of the water foamed in the daylight. But everything was dark, and I moved by sound alone. In the distance, the lighthouse beyond the Point flashed periodically as the light circled, and I headed toward it in a daze.

There was movement just ahead in the dark, farther down the cliff path. A flashlight shining in my direction so I had to raise an arm to block my eyes. The shadow of a man walked toward me, his walkie-talkie crackling. “Ma’am, you can’t be out here,” he said.

The flashlight swung back, and that was when I saw them, a glint caught in the beam of light. I felt the earth tilting.

A familiar pair of gold strappy sandals, kicked off just before the edge of the rocks.

SUMMER

2018

CHAPTER 1

There was a storm offshore at dusk. I could see it coming in the shelf of darker clouds looming near the horizon. Feel it in the wind blowing in from the north, colder than the evening air. I hadn’t heard anything in the forecast, but that meant nothing for a summer night in Littleport.

I stepped back from the bluffs, imagined Sadie standing here instead, as I often did. Her blue dress trailing behind her in the wind, her blond hair blowing across her face, her eyes drifting shut. Her toes curled on the edge, a slow shift in weight. The moment—the fulcrum on which her life balanced.

I often imagined the last thing she was writing to me, standing on the edge: There are things even you don’t know.

I can’t do this anymore.

Remember me.

But in the end, the silence was perfectly, tragically Sadie Loman, leaving everyone wanting more.

——

THE LOMANS’ SPRAWLING ESTATE had once felt like home, warm and comforting—the stone base, the blue-gray clapboard siding, doors and glass panes trimmed in white, and every window lit up on summer nights, like the house was alive. Reduced now to a dark and hollow shell.

In the winter, it had been easier to pretend: handling the maintenance of the properties around town, coordinating the future bookings, overseeing the new construction. I was accustomed to the stillness of the off-season, the lingering quiet. But the summer bustle, the visitors, the way I was always on call, smile in place, voice accommodating—the house was a stark contrast. An absence you could feel; ghosts in the corner of your vision.

Now each evening I’d walk by on my way to the guest cottage and catch sight of something that made me look twice—a blur of movement. Thinking for an awful, beautiful moment: Sadie. But the only thing I ever saw in the darkened windows was my distorted reflection watching back. My own personal haunting.

——

IN THE DAYS AFTER Sadie’s death, I remained on the outskirts, coming only when summoned, speaking only when called upon. Everything mattered, and nothing did.

I gave my stilted statement about that night to the two men who knocked on my door the next morning. The detective in charge was the same man who’d found me on the cliffs the night before. His name was Detective Collins, and every pointed question came from him. He wanted to know when I’d last seen Sadie (here in the guesthouse, around noon), whether she’d told me her plans for that night (she hadn’t), how she’d been acting that day (like Sadie).

But my answers lagged unnaturally behind, as if some connection had been severed. I could hear myself from a remove as the interview was happening.

You, Luciana, and Parker each arrived at the party separately. How did that go again?

I was there first. Luciana arrived next. Parker arrived last.

Here, a pause. And Connor Harlow? We heard he was at the party.

A nod. A gap. Connor was there, too.

I told them about the message, showed them my phone, promised she’d been writing to me when all of us were already at the party together. How many drinks had you had by then? Detective Collins had asked. And I’d said two, meaning three.

He tore a sheet of lined paper off his notepad, wrote out a list of our names, asked me to fill in the arrival times as well as I could. I estimated Luce’s arrival based on the time I’d called Sadie and Parker’s on the time I’d sent the text, asking where she was.

Avery Greer—6:40 p.m.

Luciana Suarez—8 p.m.

Parker Loman—8:30 p.m.

Connor Harlow—?

I hadn’t seen Connor come in, and I’d frowned at the page. Connor got there before Parker. I’m not sure when, I’d said.

Detective Collins had twisted the paper back his way, eyes skimming the list. That’s a big gap between you and the next person.

I told him I was setting up. Told him the first-timers always came early.

The investigation that followed was tight and to the point, which the Lomans must’ve appreciated, all things considered. The house had remained dark, since Grant and Bianca were called back in the middle of the night with word of Sadie’s death. When the cleaning company and the pool van showed up before Memorial Day—dusting out the cobwebs, shining the counters, opening up the pool—I’d watched from behind the curtains of the guesthouse, thinking maybe the Lomans would be back. They were not ones to linger in sentimentality or uncertainty. They were the type who favored commitment and facts, regardless of which way they bent.

So, the facts, then: There were no signs of foul play. No drugs or alcohol in her system. No inconsistencies in the interviews. It seemed no one had motive to hurt Sadie Loman, nor opportunity. Anyone who had a relationship with her was accounted for at the Plus-One party.

It was hard to simultaneously grieve and reconstruct your own alibi. It was tempting to accuse someone else just to give yourself some space. It would have been so easy. But none of us had done it, and I thought that was a testament to Sadie herself. That none of us could imagine wanting her dead.

The official cause of death was drowning, but there would have been no surviving the fall—the rocks and the current, the force and the cold.

She could’ve slipped, I told the detectives. This, I had wanted so badly to believe. That there wasn’t something I had missed. Some sign that I could trace back, some moment when I could’ve intervened. But it was the shoes at first that made them think otherwise. A deliberate move. The gold sandals left behind. Like she’d stopped to unstrap them on her way to the edge. A moment of pause before she continued on.

I fought it even as her family accepted it. Sadie was my anchor, my coconspirator, the force that had grounded my life for so many years. If I imagined her jumping, then everything tilted precariously, just as it had that night.

But later that evening, after the interviews, they found the note inside the kitchen garbage can. Possibly swept up in the mess of an emptied pantry, everything laid out on the counters—the result of Luce trying to clean, to bring some order, before Grant and Bianca arrived in the middle of the night. But knowing Sadie, more likely a draft that she had decided against; a commitment to the fact that no words would do.

I hadn’t seen the warnings. The cause and effect that had brought Sadie to this moment. But I knew how fast a spiral could grab you, how far the surface could seem from below.

I knew exactly what Littleport could do.

——

I WAS ALONE UP here now.

Still living and working out of the guesthouse.

The inside of the one-bedroom apartment was decorated like a dollhouse version of the main residence, with the same wainscoting and dark wood floors. But the walls were tighter, the ceilings lower, the windows thin enough that you could hear the wind rattle the edges at night. The ocean view was partially obstructed through the trees.

I sat at the desk in the living room, finishing up the last of the paperwork before bed. There had been damage at one of the rentals earlier in the week—a broken flat-screen television, the surface fractured, the whole thing hanging crookedly from the wall; and one shattered ceramic vase below the television. The renters swore it hadn’t been them, claiming an intruder while they were out, though nothing was taken, and there was no sign of forced entry.

I’d driven straight over after they called in a panic. Surveyed the scene as they pointed out the damage with trembling hands. A narrow weatherworn house we called Trail’s End located on the fringes of downtown, its faded siding and overgrown path to the coastline only adding to its charm. Now the renters pointed to the unlit path and the distance from the neighbors as a lapse in security, the potential for danger.

They promised they had locked up before leaving for the day. They were sure, implying that the fault lay on my end somehow. The way they kept mentioning this fact—We locked the doors, we always do—was enough to keep me from believing them. Or wonder whether they were trying to cover up for something more sinister: an argument, someone throwing the vase, end over end, until it connected with the television.

Well, damage done, either way. It wasn’t enough for the company to pursue, especially from a family who’d been coming for the entire month of August the last three years, despite what might be happening within those walls.

I stretched out on the couch, reaching for the remote before heading to my bedroom. I’d gotten into the habit of falling asleep with the television on. The low hum of voices in the next room, beneath the sound of the gently rattling window frame.

I’ve known enough of loss to accept that grief may lose its sharpness with time, but memory only tightens. Moments replay.

In the silence, all I could hear was Sadie’s voice, calling my name as she walked inside. The last time I saw her.

Sometimes, in my memory, she lingers there, in the entrance of my room, like she’s waiting for me to notice something.

——

I WOKE TO SILENCE.

It was still dark, but the noise from the television was gone. Nothing but the window rattling as a strong gust blew in from somewhere offshore. I flipped the switch on the bedside table lamp, but nothing happened. The electricity was out again.

It’d been happening more often, always at night, always when I’d have to find a flashlight to reset the fuse in the box beside the garage. It was a concession for living in a town like this. Exclusive, yes. But too far from the city and too susceptible to the surroundings. The infrastructure out on the coast hadn’t caught up to the demand, money or not. Most places had backup generators for the winter, just in case; a good storm could knock us off the grid for a week or more. Summer blackouts were the other extreme—too many people, the population tripled in size. Everything stretched too thin. Grid overload.

But as far as I could tell, this was localized—just me. Something an electrician should take a look at, probably.

The sound of the wind outside almost made me decide to wait it out until morning, except the charge on my cell was in the red, and I didn’t like the idea of being up here alone, with no power and no phone.

The night was colder than I’d expected as I raced down the path toward the garage, flashlight in hand. The metal door to the fuse box was cold to the touch and slightly ajar. There was a keyhole at the base, but I’d wedged it open myself earlier this month, the first time this happened.

I flipped the master switch and slammed the metal door closed again, making sure it latched this time.

Another gust of wind blew as I turned back, and the sound of a door slamming shut cut through the night, made me freeze. The noise had come from the main residence, on the other side of the garage.

I cycled through the possibilities: a pool chair caught in the wind, a piece of debris colliding with the side of the house. Or something I forgot to secure myself—the back doors left unlatched, maybe.

The lockbox for the spare key was hidden just under the stone overhang of the porch, and my fingers fumbled the code in the dark twice before the lid popped open.

Another gust of wind, another noise, closer this time—the hinges of a gate echoing through the night as I jogged up the steps of the front porch.

I knew something was wrong as soon as I slid the key into the lock—it was already unlocked. The door creaked open, and my hand brushed the wall just inside, connecting with the foyer switch, illuminating the empty space from the chandelier above.

It was then that I saw it. Through the foyer, down the hall at the back of the house. The shadow of a man standing before the glass patio doors, silhouetted in the moonlight.

“Oh,” I said, taking a step back just as he took a step closer.

I would know the shape of him anywhere. Parker Loman.

CHAPTER 2

Jesus Christ,” I said, my hand fumbling for the rest of the light switches. “You scared me to death. What are you doing here?”

“It’s my house,” Parker answered. “What are you doing here?”

Everything was light then. The open expanse of the downstairs, the vaulted ceilings, the hallway spanning the distance between me and him.

“I heard something.” I held up the flashlight as evidence.

He tipped his head to the side, a familiar move, like he was conceding something. His hair had grown in, or else he was styling it differently. But it softened his edges, smoothing out the cheekbones, and for a second, when he turned, I could see the shadow of Sadie in him.

He shifted and she was gone. “I’m surprised you’re still here,” he said. As if their local business had continued to operate for the past year on momentum alone. I almost answered: Where else would I go? But then he grinned, and I imagined I must’ve shaken him pretty good, walking in his front door unannounced.

The truth was, I had thought about leaving multiple times. Not just here but the town itself. I’d come to believe there was some toxicity hidden at its core that no one else seemed to notice. But more than the business, more than the job, I had made a life for myself here. I was too tied up in this place.

Still, sometimes I felt that staying was nothing more than a test of endurance bordering on masochism. I wasn’t sure what I was trying to prove anymore.

I could feel my heartbeat slowing. “I didn’t notice a car,” I said, taking in the downstairs, categorizing the changes: two leather bags at the base of the wide staircase, a key ring thrown on the entryway table; an open bottle on the granite island, a mug beside it; and Parker, sleeves of his button-down rolled up and collar loosened like he’d just arrived from work, not sometime in the middle of the night.

“It’s in the garage. Just drove up this evening.”

I cleared my throat, nodded to his bags. “Is Luce here?” I hadn’t heard her name in a while, but Grant kept our conversations focused on the business, and Sadie was no longer here to fill me in on the personal details of the Lomans’ lives. There’d been rumors, but that meant nothing. I’d been the subject of plenty of unfounded rumors myself.

Parker stopped at the island, a whole expanse between us, and picked up the mug, taking a long drink. “Just me. We’re taking a break,” he said.

A break. It was something Sadie would’ve said, inconsequential and vaguely optimistic. But his grip on the mug, his glance to the side, told me otherwise.

“Well, come on in. Join me for a drink, Avery.”

“I have to be at a property early tomorrow,” I said. But my words trailed off with his returning look. He smirked, pulled a second mug out, and poured.

Parker’s expression said he knew exactly who I was, and there was no point in pretending. Didn’t matter that I was currently overseeing all of the family’s properties in Littleport—six summers, and you get to know a person’s habits pretty well.

I’d known him longer than that. It was the way of things, if you’d grown up here: the Randolphs, on Hawks Ridge; the Shores, who’d remodeled an old inn at the corner of the town green, then proceeded to have a series of affairs and now shared their massive plot like a child of divorce, never seen at the same time; and the Lomans, who lived up on the bluffs, overlooking all of Littleport, and then expanded, their tendrils spreading out around town until their name was synonymous with summer. The rentals, the family, the parties. The promise of something.

The locals referred to the Lomans’ main residence as the Breakers, a subtle jab that once bonded the rest of us together. It was partly a nod to the home’s proximity to Breaker Beach and partly an allusion to the Vanderbilt mansion in Newport, a level of wealth even the Lomans couldn’t aspire to. Always whispered in jest, a joke everyone was in on but them.

Parker slid the second mug across the surface, liquid sloshing out the side. He was this haphazard only when he was well on his way to drunk. I twisted the mug back and forth on the countertop.

He sighed and turned around, taking in the living room. “God, this place,” he said, and then I picked up the drink. Because I hadn’t seen him in eleven months, because I knew what he meant: this place. Now. Without Sadie. Their enlarged family photo from years earlier still hung behind the couch. The four of them smiling, all dressed in beige and white, the dunes of Breaker Beach out of focus in the background. I could see the before and after, same as Parker.

He raised his mug, clanked it against mine with enough force to convey this wasn’t his first drink, just in case I hadn’t been able to tell.

“Hear, hear,” he said, frowning. It was what Sadie always said when we were getting ready to go out. Shot glasses in a row, a messy pour—hear, hear. Fortifying herself while I was going in the other direction. Glasses tipped back and the burn in my throat, my lips on fire.

I closed my eyes at the first sip, felt the loosening, the warmth. “There, there,” I answered quietly, out of habit.

“Well,” Parker said, pouring himself half a glass more. “Here we are.”

I sat on the stool beside him, nursing my mug. “How long are you staying?” I wondered if this was because of Luce, if they’d been living together and now he needed somewhere to escape.

“Just until the dedication ceremony.”

I took another sip, deeper than intended. I’d been avoiding the tribute to Sadie. The memorial was to be a brass bell that didn’t work, that would sit at the entrance of Breaker Beach. For all souls to find their way home, it would say, the words hand-chiseled. It had been put to a vote.

Littleport was full of memorials, and I’d long since had my fill of them. From the benches that lined the footpaths to the statues of the fishermen in front of the town hall, we were becoming a place in service not only to the visitors but to the dead. My dad had a classroom in the elementary school. My mom, a wall at the gallery on Harbor Drive. A gold plaque for your loss.

I shifted in my seat. “Your parents coming up?”

He shook his head. “Dad’s busy. Very busy. And Bee, well, it probably wouldn’t be best for her.” I’d forgotten this, how Parker and Sadie referred to Bianca as Bee—never to her face, never in her presence. Always in a removed affect, like there was some great distance between them. I thought it an eccentricity of the wealthy. Lord knows, I’d discovered enough of them over the years.

“How are you doing, Parker?”

He twisted in the stool to face me. Like he’d just realized I was there, who I was. His eyes traced the contours of my face.

“Not great,” he said, relaxing in his seat. It was the alcohol, I knew, that made him this honest.

Sadie had been my best friend since the summer we met. Her parents had practically taken me in—funding my courses, promising work if I proved myself worthy. I’d been living and working out of their guesthouse for years, ever since Grant Loman had purchased my grandmother’s home. And after all this time when we’d occupied the same plane of existence, Parker had rarely made a comment of any depth.

His fingers reached for a section of my hair, tugging gently before letting it drop again. “Your hair is different.”

“Oh.” I ran my palm down the side, smoothing it back. It had been less an active change and more the path of least resistance. I’d let the highlights grow out over the year, the color back to a deeper brown, and then I’d cut it to my shoulders, keeping the side part. But that was one of the things about seeing people only in the summer—there was nothing gradual about a change. We grew in jolts. We shifted abruptly.

“You look older,” he added. And then, “It’s not a bad thing.”

I could feel my cheeks heating up, and I tipped the mug back to hide it. It was the alcohol, and the nostalgia, and this house. Like everything was always just a moment from bursting. Summer strung, Connor used to call it. And it stuck, with or without him.

“We are older,” I said, which made Parker smile.

“Should we retire to the sitting room, then?” he said, but I couldn’t tell whether he was making fun of himself or me.

“Gonna use the bathroom,” I said. I needed the time. Parker had a way of looking at you like you were the only thing in the world worth knowing. Before Luce, I’d seen him use it a dozen times on a dozen different girls. Didn’t mean I’d never thought about it.

I walked down the hall to the mudroom and the side door to the outside. The bathroom here had a window over the toilet, uncovered, facing the sea. All of the windows facing the water were left uncovered to the view. As if you could ever forget the ocean’s presence. The sand and the salt that seemed to permeate everything here—lodged in the gap between the curb and the street, rusting the cars, the relentless assault on the wooden storefronts along Harbor Drive. I could smell the salt air as I ran my fingers through my hair.

I splashed water on my face, thought I caught a shadow passing underneath the door. I turned off the faucet and stared at the knob, holding my breath, but nothing happened.

Just a figment of my imagination. The hope of a long-ago memory.

It was a quirk of the Loman house that none of the interior doors had locks. I never knew whether this was a design flaw—a trade-off for the smooth antique-style knobs—or whether it was meant to signify an elite status. That you always paused at a closed door to knock. If it inspired in people some sort of restraint; that there would be no secrets here.

Either way, it was the reason I’d met Sadie Loman. Here, in this very room.

——

IT WAS NOT THE first time I’d seen her. This was the summer after graduation, nearly six months after the death of my grandmother. A slick of ice, a concussion followed by a stroke that left me as the last Greer in Littleport.

I had ricocheted through the winter, untethered and dangerous. Graduated through the generosity of makeup assignments and special circumstances. Become equally unpredictable and unreliable in turn. And still there were people like Evelyn, my grandmother’s neighbor, hiring me for odd jobs, trying to make sure I got by.

All it did was bring me closer to more of the things I didn’t have.

That was the problem with a place like this: Everything was right out in the open, including the life you could never have.

Keep everything in balance, in check, and you could open a storefront selling homemade soap, or run a catering company from the kitchen of the inn. You could make a living, or close to it, out on the sea, if you loved it enough. You could sell ice cream or coffee from a shop that functioned primarily four months of the year, that carried you through. You could have a dream as long as you were willing to give something up for it.

Just as long as you remained invisible, as was intended.

——

EVELYN HAD HIRED ME for the Lomans’ Welcome to Summer party. I wore the uniform—black pants, white shirt, hair back—that was meant to make you blend in, become unnoticeable. I was sitting on the closed lid of the toilet, wrapping the base of my hand in toilet paper, silently cursing to myself and trying to stop the blood, when the door swung open and then quietly latched again. Sadie Loman stood there, facing away, with her palms pressed to the door, her head tipped down.

Meet someone alone in a bathroom, hiding, and you know something about her right away.

I cleared my throat, standing abruptly. “Sorry, I’m just . . .” I tried to edge by her, keeping close to the wall as I moved, trying to remain invisible, forgettable.

She made no effort to hide her assessing eyes. “I didn’t know anyone was in here,” she said. No apology, because Sadie Loman didn’t have to apologize to anyone. This was her house.

The pink crept up her neck then, in the way I’d come to know so well. Like I’d been the one to catch her instead. The curse of the fair-skinned, she’d explained later. That and the faint freckles across the bridge of her nose made her look younger than her age, which she compensated for in other ways.

“Are you okay?” she asked, frowning at the blood seeping through the toilet paper wrapped around my hand.

“Yeah, I just cut myself.” I pressed down harder, but it didn’t help. “You?”

“Oh, you know,” she said, waving her hand airily around. But I didn’t. Not then. I’d come to know it better, the airy wave of her hand: All this, the Lomans.

She reached her hand out for mine, gesturing me closer, and there was nothing to do but acquiesce. She unwound the paper, leaning closer, then pressed her lips together. “I hope you have a tetanus shot,” she said. “First sign is lockjaw.” She clicked her teeth together, like the sound of a bone popping. “Fever. Headaches. Muscle spasms. Until finally you can’t swallow or breathe. It’s not a quick way to die, is what I’m saying.” She raised her hazel eyes to mine. She was so close I could see the line of makeup under her eyes, the slight imperfection where her finger had slipped.

“It was a knife,” I said, “in the kitchen.” Not a dirty nail. I assumed that was what tetanus was from.

“Oh, well, still. Be careful. Any infection that gets to your bloodstream can lead to sepsis. Also not a good way to go, if we’re making a list.”

I couldn’t tell whether she was serious. But I cracked a smile, and she did the same.

“Studying medicine?” I asked.

She let out a single bite of laughter. “Finance. At least that’s the plan. Fascinating, right? The path to death is just a personal interest.”

This was before she knew about my parents and the speed at which they did or did not die. Before she could’ve known it was a thing I often wondered, and so I could forgive her the flippancy with which she discussed death. But the truth was, there was something almost alluring about it—this person who did not know me, who could toss a joke about death my way without flinching after.

“I’m kidding,” she said as she ran my hand under the cold water of the sink, the sting numbing. My stomach twisted with a memory I couldn’t grasp—a sudden pang of yearning. “This is my favorite place in the world. Nothing bad is allowed to happen here. I forbid it.” Then she rummaged through the lower cabinet and pulled out a bandage. Underneath the sink was an assortment of ointments, bandages, sewing kits, and bathroom products.

“Wow, you’re prepared for anything here,” I said.

“Except voyeurs.” She looked up at the uncovered window and briefly smiled. “You’re lucky,” she said, smoothing out the bandage. “You just missed the vein.”

“Oh, there’s blood on your sweater,” I said, appalled that some part of me had stained her. The perfect sweater over the perfect dress on this perfect summer night. She shrugged off the sweater, balled it up, threw it in the porcelain pail. Something that cost more than what I was getting paid for the entire day, I was sure.

She sneaked out as quietly as she had entered, leaving me there. A chance encounter, I assumed.

But it was just the start. A world had opened up to me from the slip of a blade. A world of untouchable things.

——

NOW, CATCHING SIGHT OF myself in that same mirror, splashing water on my face to cool my cheeks, I could almost hear her low laughter. The look she would give me, knowing her brother and I were alone in a house, drinking, in the middle of the night. I stared at my reflection, the hollows under my eyes, remembering. “Don’t do it.” I whispered it out loud, to be sure of myself. The act of speaking held me accountable, contained something else within me.

Sometimes it helped to imagine Sadie saying it. Like a bell rattling in my chest, guiding me back.

——

PARKER WAS SPRAWLED ON the couch under the old family portrait, staring out the uncovered windows into the darkness, his gaze unfocused. I didn’t know if it was such a good idea to leave him. I was more careful now. Looking for what was hidden under the surface of a word or a gesture.

“You’re not going to finish that drink, are you,” he said, still staring out the window.

A drop of rain hit the glass, then another—a fork of lightning in the distance, offshore. “I should get back before the storm hits,” I said, but he waved me off.

“I can’t believe they’re having the party again,” he said, like it had just occurred to him. “A dedication ceremony and then the Plus-One.” He took a drink. “It’s just like this place.” Then he turned to me. “Are you going?”

“No,” I said, as if it had been my own decision. I couldn’t tell him that I didn’t know anything about any Plus-One party this year, whether it was happening again or where it would be. There were a handful of weeks left in the season, and I hadn’t heard a word about it. But he’d been here a matter of hours and already knew.

He nodded once. In the Loman family, there was always a right answer. I had learned quickly that they were not asking questions in order to gather your thoughts but to assess you.

I rinsed out my mug, keeping my distance. “I’ll call the cleaners if you’re going to be staying.”

“Avery, hold up,” he said, but I didn’t wait to hear what he was going to say.

“Sleep it off, Parker.”

He sighed. “Come with me tomorrow.”

I froze, my hand on the granite counter. “Come with you where?”

“This meeting with the dedication committee,” he said, frowning. “For Sadie. Lunch at Bay Street. I could use a friend there.”

A friend. As if that’s what we were.