6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Will the dark secrets of a small mountain town finally be revealed? Ten years ago, Abigail Lovett fell into a job she loves, working at the Passage Inn, nestled in the resort town of Cutter's Pass, just off the Appalachian Trail. Now, the string of unsolved disappearances that haunts the town is again thrust into the spotlight when Landon West, a journalist investigating the story, himself disappears. Abigail still feels like an outsider within the community she now calls home, and when Landon's brother shows up to look for him, she senses the town closing ranks. Then she finds incriminating evidence that may finally bring the truth to light and discovers how little she knows about her co-workers, neighbours, and even those closest to her...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

THELASTTOVANISH

ALSO BY MEGAN MIRANDA

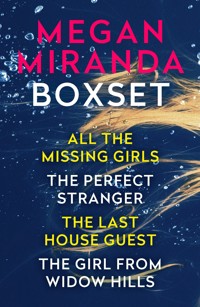

Such a Quiet Place

The Girl from Widow Hills

The Last House Guest

The Perfect Stranger

All the Missing Girls

THELASTTOVANISH

MEGAN MIRANDA

First published in the United States of America in 2022 by Marysue Rucci Books, Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

First published in Great Britain in 2022 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Megan Miranda, 2022

The moral right of Megan Miranda to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 83895 751 3

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 596 0

E-Book ISBN: 978 1 83895 597 7

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk/corvus/

For my family

A NOTORIOUS HISTORY

These are the relevant statistics of Cutter’s Pass, North Carolina: The town covers roughly four square miles of a valley, tucked against the base of a mountain ridge. Its main economy is tourism, due to the proximity of an access point to the Appalachian Trail. The most recent census puts the population at just over 1,000 permanent residents. Six visitors have gone missing in the last twenty-five years. As a result, some have called it the most dangerous town in the state.

Here’s what the people of Cutter’s Pass want you to know: It’s a picturesque valley, named almost a century earlier for a path through the nearby mountains, which had proven historically difficult in the winter. Yes, they’ve had a string of bad luck with the missing visitors, but there’s nothing particularly dangerous about the area now. The disappearances are just coincidence. Statistics, even. Twenty-five years, just a few incidents.

It’s easy to believe, if you want. It’s just as easy to disbelieve. But whichever person you are, believer or disbeliever, Cutter’s Pass welcomes you equally.

The truth is—

PART 1

Landon West

Date missing: April 2, 2022

Last seen: Cutter’s Pass, North Carolina

The Passage Inn

AUGUST 3, 2022

CHAPTER 1

HE ARRIVED AT NIGHT, in the middle of a downpour, the type of conditions more suitable for a disappearance.

I was alone in the lobby—removing the hand-carved walking sticks from the barrel beside the registration desk, replacing them with our stash of sleek navy umbrellas—when someone pushed through one of the double doors at the entrance. The sound of rain cascading over the gutters; the rustle of hiking pants; the screech of wet boots on polished floors.

A man stood just inside as the door fell shut behind him, with nothing but a black raincoat and some sob story about his camping plans.

Nothing to be afraid of: the weather, a hiker.

I was only half listening at first, his request buried under a string of apologies. I’m so sorry, I’m usually more prepared than this and I know this is a huge inconvenience but—

“We can get you taken care of,” I said, making my way behind the desk, where I had the room availability list already pulled up on the single computer screen. This was the type of rain that drove hikers off the mountain—sudden and fierce enough to shake their resolve, when they’d give a second thought to their gear, their stamina, their will. Unlike him, I had been ready for this.

The back of our property ended where the local access trail began: It was marked by a small wooden sign leading day hikers on a path to the falls, but the trail then continued on in a steep ascent, pressing upward until it ultimately collided with the great Appalachian beyond. Our guests loved the convenience, the accessibility, that touch of the wild—the mountain looming, so close, from the other side of their floor-to-ceiling windows.

From the ridge of that mountain, at the T intersection of the two trails, I knew, you could see us, too: the dome of the inn, and the town just beyond, with the steeple of the church pushing up through the treetops; the promise of civilization. Sometimes, on nights like this, they spilled down the mountain like ants scurrying out of a poisoned mound, searching for a place of last resort. Our lights drawing them closer, the first sign of respite off the trail.

Sometimes if there was only one room, strangers would join forces and bunk up, in the spirit of things.

Right now, it was high season and we were booked solid in the main building, but three of the four outside cabins were vacant. The accommodations out there were more rustic, mainly used for either long-term stays or purposes such as this.

The man was still standing on the far side of the lobby, hands cupped in front of his mouth, as if the storm carried a chill. I saw his gaze flick to the freestanding fireplace in the center of the room. “You’re going to have to come a little closer to check in,” I said.

He laughed once and lowered the hood of his raincoat as he crossed the lobby, shaking out his hair, and then his arms, in an uncannily familiar gesture. I felt my smile falter and tried to cover for it with a glance toward the computer screen, running through the possibilities. A return visitor. Someone I’d seen in town earlier this week. Nothing. Coincidence.

“Here we go,” I said, turning my attention his way again, hoping the sight of him so close would trigger a memory, place him in context: brown hair halfway between unkempt and in style; deepset blue eyes; somewhere in his thirties; no wedding ring; the sharp line of a white scar on the underside of his jaw, which I could only see because he was a solid head taller. I imagined him falling during a hike, hands braced for impact, chin grazing rock; I imagined a hockey stick to the face, helmet dislodged, blood on ice.

I did this sometimes, imagined people’s stories. It was a habit I was actively trying to break.

I was sure I knew him from somewhere, but I couldn’t place it, and I was usually good at this. I remembered the repeat visitors, could pull a name from three years earlier, recognizing those who’d gotten married or divorced, even, changing names and swapping partners. I paid attention, kept notes, filed away details. The stories I imagined for them sometimes helped.

He looked behind him at the empty lobby before leaning one arm on the distressed wooden countertop between us. “I’m so sorry,” he repeated, though I wasn’t sure whether he was referring to his lack of reservation or the puddles of water he had trailed across the wide plank floor. “It’s just, I left my wallet somewhere. Out there.” His raincoat rustled as he gestured toward the door. He was pointing in the opposite direction of the mountain, but I let that go because of the dark and the rain, and because I knew how disorienting it could get out there, on a bad night. “I had some cash in my car, though,” he said, hand stuffed deep into the pocket of his coat before he pulled out a damp roll of twenties. “For emergencies.”

He extended the money my way, an offering held between the tips of his fingers.

Hikers sometimes arrived like this, it wasn’t unheard of, but I started reassessing him. The clean fingernails. The collar of his blue T-shirt, just visible, still dry. The familiar squeak of too-new rubber-soled boots, before they’d gotten any good miles on them.

Celeste wouldn’t approve of this—a man with no ID and no credit cards, showing up just before closing. She’d say I needed to look after myself first of all, and then the guests, and then the inn. Would warn me that we were alone up here, that the only way to project control was to make sure others didn’t think they held the reins. Celeste would rather the lost customer than the lost upper hand. She’d say, So sorry, we’re all full, and she’d mention the campgrounds down by the river, the rentals over the storefronts, the motel in the next town. But I’d been known to make some exceptions. I didn’t like the idea of leaving anyone alone out there, especially on nights like this. Besides, I was sure he’d been here before at some point.

“No problem,” I said, “Mr.—”

His gaze was drifting around the lobby again, taking everything in, like he’d never seen this place before: the fireplace encased in stone and glass, visible from all angles, logs piled up into perfect pyramids on either side; the two-story arch of the dome with the exposed wood beams, the large picture windows that made up the entirety of the far wall, for the best views; the keys hanging from the pegboard in a locked display behind me.

“Sir?” I repeated.

He finally made eye contact. “Clarke,” he said, clearing his throat. “With an e.” He smiled apologetically, a little lopsided, a dimple in his left cheek—another twinge of familiarity.

The name didn’t ring a bell.

“Sure thing, Mr. Clarke. Let’s see what I can do for you.”

Cutter’s Pass was a seasonal, small-town haven: river guides and zip lines; a well-maintained campground a half mile outside downtown; horseback tours and an abundance of hiking trails forking off into the surrounding mountains. There were three types of visitors we typically got at the inn. The high-end vacationers who wanted a taste of rustic without actually roughing it; the hikers who thought they were ready to rough it, and discovered they were not, asking for a cabin, or any availability please; and the tourists who came for our eerie history, our notoriety—usually groups of friends who asked a lot of questions and drank a lot of beer at the tavern down the road and stumbled in late, laughing and clinging to one another, like they had escaped something. They always seemed surprised by the reality of Cutter’s Pass—that it was more REI and craft beer, overpriced farmers’ markets and upscale accommodations, less whatever stereotype of Appalachia had taken root in their heads.

From the way this man was looking around the place, and his questionable story, I would’ve put my money on category three. Except. That familiar gesture. That dimple when he smiled.

I slid a sheet of paper in front of him. “All right,” I said, “jot down your license plate so we don’t tow you.”

He blinked twice, mouth slightly open, a single drop of rain trailing along the edge of his jaw, toward the scar. “Tow me?”

“Lots of people try to park here to get to the mountain,” I explained. “The spots are for guests.”

“Oh, um, I don’t know it by heart . . .”

God, he was bad at this.

“Make and color, then,” I said. “And state, if you remember that.” I smiled at him, and he laughed.

“I do,” he said. I watched as he scrawled down Audi, black. Maryland. I felt myself holding my breath. It clicked, where I’d seen him, why he looked so familiar. The family picture with the joint statement. The reward offered in a long-shot plea for help.

I tried to keep my smile in place: cordial, careful. “Maryland, huh? Long way from home,” I said.

“Yes, well, next time I’ll stick to a beach vacation. Lesson learned.”

He was charming, which almost made up for the lack of plan, but wouldn’t get him very far here.

I felt for him, really. I’d been an outsider for years; to those who’d grown up here, I probably still was.

“Any preference on room?” I asked.

“Oh,” he said, narrowing his eyes, looking toward the balcony of the second floor, just beyond the dome of the lobby. “I . . . I wouldn’t know.”

My heart was too soft, I knew this. I unlocked the display case on the wall behind me and took the key off the hook for Cabin Four. I knew what he wanted; what he was here for. “You look just like him,” I said.

His entire body deflated, almost like he was making himself prostrate, his forehead down to the counter between us before he stood again, as if he were unveiling someone new.

“I’m sorry,” he said, face contorted into a grimace. It was the first time I believed him.

“No,” I said. “I get it. Really. I understand. I would do the same.”

He pulled a wallet out of his back pocket, took a deep breath in and out, started again. “Trey West,” he said, leaving a pause for me to fill. A question, an offering.

“Abby,” I said.

“Abby,” he repeated, turning over his license, a credit card. “I’m not good at pretending. It’s a relief.”

It was his brother, Landon, who was good at that. We didn’t know he was a journalist when he came to stay. We’d thought he was trying his hand at writing a book, that he was on a personal retreat, that he needed the peace and quiet, the lack of distractions, the ambiance—that’s what he’d told us. We’d thought he was here to get away from something. Not that he was here for something instead. But those things were hard to differentiate on the surface. It wasn’t until he disappeared that we knew the truth.

I didn’t know what Trey was looking for all these months later. Whether he thought there was still something worth finding, that the police and the searchers had all missed; whether he was here to pay his respects, hoping for some sort of closure.

Closure was a hard thing to come by here.

“It’s not what I expected,” Trey said as I charged the night to his card.

I wasn’t sure whether he meant the inn or the entire town. The road into town climbed up for a stretch of miles before swerving down again, narrowing as it dipped from the mountains into the valley, vegetation pushing closer and creeping over the guardrails. It was a drive you didn’t want to do at night, riding the brakes as the curves grew tighter, branches arcing over the pavement. But then the trees opened up, and Cutter’s Pass presented itself, a lost city. A found oasis.

“It never is,” I said. There was always a slight disorientation when you arrived, nothing quite as expected from the drive in. The inn appeared older than it was from the outside, with the weatherworn cabins set back from the main three-story structure, and the forest steadily encroaching over the cleared acreage, but that was just how fast nature worked. Inside, the fireplace was gas; the logs, just for show; the antique locks on all the guest room doors could be overridden with an electronic badge.

It was already clear that Trey was different from his brother, who was closed off and blended in, whom I didn’t even notice for the first four days of his stay, because Georgia checked him in and could only remember, when pressed, that he had asked for the Wi-Fi password, and she had told him the service didn’t reach the cabins, that it was slow and barely consistent in the main building as well, which was why we had to keep the credit card slide under the register, old-fashioned carbon copies that people thought quaint, so it worked in our favor.

Other things that worked in our favor but were neither authentic nor necessary: the wooden key rings with the room names etched in by hand; the poker beside the fireplace, angled just so.

Things here were designed to appear more fragile than they were, but reinforced, because they had to be. We lived in the mountains, on the edge of the woods, subject to the whims of weather and the forces of nature.

The large guest room windows were practically soundproof. Frosted skylights in the upper-floor halls echoed the fall of rain or sleet, but were fully resistant to a branch lost to a storm. There were tempered glass panels in the thick wooden doors at the entrance, which could hypothetically stop a bullet, but thankfully had never been tested.

I pulled one of the umbrellas from the barrel, each a uniform navy blue with a tastefully small logo: a single, bare tree, white branches unfurling against the evening sky.

“Come on,” I said, “I’ll show you the way.”

This was not part of my job, but I couldn’t help myself. I never could.

OUTSIDE, THE RAIN WAS unrelenting, puddles forming in the gravel lot, water seeping into my shoes. Trey West had to duck to fit under the shared umbrella, his arm brushing up against mine as we walked.

“The cabins are this way,” I explained, gesturing to the trail of marked lighting along the brick path on the other side of the parking lot.

We passed his car, that black Audi with the Maryland plates, on the far end of the lot, and he looked at me sheepishly.

“Is it always this dark?” he asked.

“Yes,” I answered, because it wasn’t really that dark out front, all things considered, but he must’ve had an entirely different frame of reference. The lit pathway did a fair enough job, along with the lights of the main building, both kept on from dusk to dawn. From the edge of this lot, even, you could see the road slope down into the town center: a geometric grid of antique shops and breweries and cafés, stores that specialized in expert hiking apparel or kitschy tourist gear, all named for the thing that could’ve been our downfall, but seemed to put us on the map instead.

Down there, you could find the Last Stop Tavern; Trace of the Mountain Souvenirs; the Edge, which sold camping gear and rented out lockers but also featured a menu of coffee and hot chocolate and beer, depending on the time of day; and CJ’s Hideaway, a top restaurant of the western Carolinas, with its entrance tucked in a back alley, a commitment to the con, even though it boasted a growing waiting list on most nights during peak season. Each storefront a subtle nod to what the rumors implied: that there was something hidden under the surface here. Some secret only we knew, that we weren’t letting on.

The town was best known, and we weren’t known for much, for the unsolved disappearance of four hikers more than two decades earlier. The Fraternity Four, they were called, even though they hadn’t been members of any frat together. But they were in their twenties, youthful and carefree, and they had last been spotted here in town, had set off toward the Appalachian and were never seen again.

Here one moment in Cutter’s Pass, gone the next. No clues, no leads. Just vanished. Over the years, their story had morphed into something of an urban legend, layers added with each retelling, rumors spreading in absentia.

Maybe the mystery would’ve faded with time, attributed to circumstance, buried with history, if not for the string of disappearances that continued to follow, with haunting regularity.

Most recently: Landon West, onetime resident of Cabin Four. He’d vanished four months before, in early April, when the inn was still ramping up to high season.

We didn’t notice, at first.

His disappearance had kicked it all up again: the stories, the press, the headlines calling us the most dangerous town in North Carolina.

It didn’t matter that the first thing a visitor saw when they passed the sign for Cutter’s Pass and took the wide bridge over the river was a welcome center and, across the street, the sheriff’s office. Didn’t matter that there were bright painted signs for rafting and horseback riding and adventure tours around the town green, where people milled around each morning as the vendors set up for the day. Or that thousands of visitors came through our small town to experience all we had to offer. The simple truth was that Landon West had vanished on our watch, just like all the rest.

“This is you,” I said as the path snaked off to the string of cabins, set back in the trees. There were technically only two cabin buildings, but we had subdivided them with a poorly insulated wall, the separate doors side by side in the middle of each loghome-style building. The only light coming from any of them was the soft glow of the floor lamp in Cabin One, visible in the curtain gaps of the front window. If Trey wanted real dark, he could walk the twenty yards into the trees around the back of his cabin and face the mountain.

I handed Trey the umbrella, slid the key into the lock of Cabin Four, felt the gust of cold as I opened the door, my hand stretching for the switch on the inside wall. Here, the wood paneling gave way to smaller windows that slid open on the front and back walls, to let in the fresh mountain air. There was a heating unit under the back window, for off-season stays.

The cabin furniture was simple and spare: a wood dresser, a nightstand, a four-poster bed with a quilted blanket, a desk and hard-back chair. Everything was shades of brown, except for the hotel guidebook, a white three-ring binder of information, perfectly centered on the surface of the desk.

Trey remained on the other side of the entrance, still holding the umbrella over his head. Now he was looking at the place Landon had once slept, the chair he’d once sat in, the place at the foot of the bed where Georgia had found his suitcase, mostly packed but still opened, only his hiking boots noticeably missing.

“Okay, well, I’ll leave you to get settled,” I said. I took the umbrella from his hand, which prompted him to finally step inside, switching places with me. He looked shell-shocked, unprepared. “If you need anything, the phone at the front desk will reach me.”

“Thank you, Abby,” he said, one hand on the door.

My hand lingered over his for a moment as I placed the key in his open palm, cold and wet and unsure. It took some time to get your bearings here. “Welcome to the Passage.”

CHAPTER 2

GEORGIA WAS STANDING AT the registration desk, the inn’s landline phone halfway to her ear, when I returned.

“The lines are down,” she said as I shook the rain from the umbrella and leaned it in a groove beside the entrance. She held that same pose, that same haunted expression, as a door opened somewhere on the second floor—the cry of a hinge I’d have to get fixed.

“Probably the rain,” I said as I crossed the lobby. It was more the wind than the rain that managed to cut us off most times, though we weren’t the only ones. The entire grid of the town center had been known to lose power from a downed tree limb—or, once, a car that collided with a telephone pole. It was that sort of night.

“I heard it ringing,” she said, quieter this time. “It just kept going, and I came out to answer it, but . . .” I took the phone she extended my way—nothing.

Well, not quite nothing. There was a low clicking sound coming from the receiver, something between dead air and static. It had happened before.

“It’ll come back,” I said, replacing the phone in its cradle. Georgia’s gaze flicked to the dark windows, like she expected something to be out there, watching back. A year working here, and she still wasn’t accustomed to the whims of the weather. The coincidences she took as signs. The sound of the local wildlife outside our windows at night. The dangers she feared could exist behind a dropped phone call, a missed connection.

When she’d first arrived, I couldn’t help but notice our similarities: We’d both come to the area soon after losing a parent, and we’d both chosen to remain—a waypoint that had turned permanent. It took longer to notice our differences: Georgia seemed to process everything by sharing, expecting me to do the same. She said whatever she was thinking, airing her insecurities, and her fears.

But Georgia always seemed on high alert, just by nature of the shape of her face—narrow and fine boned, with large brown eyes and her blonde hair in a pixie cut. You could almost imagine her as some mystical creature, something you might catch a glimpse of hiding between the trees, if not for the fact that she was nearly six feet tall, sharp angles and long limbs and very hard to miss.

“Was that a hiker you just checked in?” she asked.

I shook my head, straightening the paperwork into the binder behind the desk, just to have something to do with my hands. “Actually, it was Landon West’s brother,” I said without making eye contact. I could imagine her expression well enough.

She stood perfectly still, waiting for me to look up. When I finally did, I lifted one shoulder, as in, I know.

“Are you going to tell Celeste?” she asked.

“Wasn’t planning on it.” After nearly a decade of working with her, Celeste now paid me to keep the details from reaching her, content to spend her time in a semiretirement. And I wasn’t sure whether this was a problem just yet.

I started closing up for the evening, shutting down the computer, gathering anything of value to store in the office behind us, which would remain locked until the morning.

“How much longer until this rain breaks?” Georgia asked, pulling out her cell and taking it into the back office, which was the best place to get any signal here—the closest to the town center you could get, the better. “I can’t get any bars,” she added, her voice going tight. She’d been on edge to some degree since Landon West’s disappearance in April, and it didn’t take much to push her over now.

“Soon, I think,” I said, for no other reason than wanting to ease her nervous energy, which had only succeeded in making me anxious as well. The weather; the phone lines; Trey West’s arrival— like there was something beginning. Something gathering force. I shook it off as I tucked the locked case of receipts and cash under my arm; this was why Georgia rarely worked the late shift.

“Abby,” Georgia called from the back office, her voice even higher, tighter.

I stepped around the corner, where she faced the dark windows over the table we used both as a desk and for meals. I’d often stood in that very spot to send a text, or upload a photo to the inn’s social media accounts. The rain sounded like it was indeed letting up, though the weather app visible on her cell phone screen was still blank and searching. She pressed a single pointer finger against the glass, turning to face me. “Cory’s on his way up with a group.”

Rain or Shine, that was his motto. Pretty much the only rule of his tours, that I could tell. “I thought he only went to the woods on day trips,” I said. It was too dark, too pointless, to take visitors out there in the night. Never mind the current state of things.

But I felt Georgia’s eyes on me as I slid the money drawer into a secondary safe in the closet. “He added Landon West to the circuit a couple weeks back.”

“You can’t be serious,” I said, joining her at the window, face pressed close to the cold glass. The case was barely four months old—dormant, but definitely not closed. I could just barely see the dancing beams of the flashlights heading up the steep incline in the dark.

“Someone should tell him,” Georgia said.

I stared at the side of her face, the plea already forming. I’d warned her about Cory, but some people have to figure things out for themselves.

At the tail end of last summer, when I was still showing Georgia around Cutter’s Pass, I brought her along on a night out, introduced her to the seasonal workers who were then in their last weeks, half of whom, despite their promises and drunken assurances, we would never see again. I felt Georgia picking up on it, sliding into it, the wild energy that pulled at everyone then, the impermanence of our choices. These people who wouldn’t remember us, just as we wouldn’t remember them. In a year, two, they’d be nothing more than the redhead who broke her wrist working the zip line; the kid from Texas who wore a cowboy hat on the river.

The only reliable fixture of that world was Sloane, who’d managed the river center from spring through fall for five years running. She’d become my closest friend, another in-betweener—not a temporary employee, but not someone with deep roots here, either.

That night, as we’d closed out the evening at the Last Stop—a tradition, a calling—we ran into Cory, who’d said, Aren’t you going to introduce me to your friend, Abby? I’d given Georgia a not-so-subtle shake of the head, which she pointedly ignored. Georgia answered for herself, with one long, fine-boned arm extended his way.

Georgia barely knew me then, no better than the seasonal workers who would soon disappear. Had no reason to trust what I was saying, which was: If you’re planning to stay, Cory was unavoidable, infallible. This was not a choice that could be forgotten.

At least it gave us something else to bond over now. Though it took everything within me to bite my tongue when she’d say, I don’t want to deal with him.

“Abby?” she pleaded, as the shadowed mass of the tour group drew nearer.

“Shit,” I said, racing for the exit, grabbing the umbrella, and pushing out into the storm once more.

FROM MY SPOT IN the parking lot, I watched as the group in dark hoods crested the top of the steep drive, huddled close together, faces low, like some sort of cult. Even in the distance, I could pick out Cory Shiles, the glow of the bottom half of his face, square jaw, a familiar regret. That tattoo of ivy creeping up the side of his neck as the light swung back and forth from his hand. He had a lantern, for God’s sake.

Cory ran something between a ghost tour and an excursion for rubberneckers. Thirty bucks for an all-weather guided experience of the history of Cutter’s Pass that started and ended at the Last Stop Tavern in town. So people could liquor up both before and after. He brought paying customers to the sights of the disappearances, showed them where each person had been spotted in town earlier. Told them what we knew of the missing, what the police had uncovered, and where the investigations had stalled.

Cory shared theories that none of us really believed: a hidden network of caves with an underground cult; a man in the mountains who had supposedly lived off grid for decades, protecting the land he deemed his own. And he told some we believed a little more, about animals and weather and how easy it was to disappear in a place like this; about people who might not want to be found. All mixed in with rumors about lines of latitude and magnetic fields, like this was the Bermuda Triangle and not four square miles of solid ground with a well-defined perimeter.

Cory hadn’t noticed me yet, his arms wide as he was telling some story that was lost to the rain, and the crowd.

“What about the people here?” I heard one woman shout from the back of the group. “Especially since all the missing were visitors? Were there ever any suspects in town?”

“The police have been through this place with a fine-tooth comb. More times than I can remember,” he answered, his voice sliding smooth as honey over the crowd. “Have you ever known a place to keep a secret for over two decades? Have you met me?”

Some laughs, a few smiles visible in the dancing lights. This was how he got the tips. That gosh-darn attitude, I’ll tell you my secrets for a beer, friend. It wasn’t true. Cory Shiles would take his secrets to the grave.

“Cory,” I called, sharp and deliberate.

He turned my way, lantern illuminating the white of his teeth. “Well, hey there, Abby!” he called back, too friendly, not reading my tone—or, more likely, choosing to ignore it. “We’re in luck tonight, this here is Abby Lovett, manager of—”

I gave him a single shake of the head, and he handed the lantern to the woman beside him, wide-eyed and eager. “Excuse me for one second, folks.”

I waited until he was out of earshot of the group, who were watching this interaction closely. I kept my voice low, my teeth clenched. “Tell me you did not add us to your ghost tour, for the love of God,” I said.

He grinned, rain hitting the hood of his coat, the top of his boots. “It’s not a ghost tour, Abby. We’re a historical walking tour—”

“He went missing four months ago, Cory. People are still looking.”

Cory took one step back, his shoulders rising and falling. “Just giving the customers what they want.”

I took a step forward, to keep this discussion private. “His brother just checked in,” I said.

The smile fell from his face; he craned his neck, taking in the second-floor windows of the inn over my shoulder. “Where’d you put him?”

“Same room,” I said. “Cabin Four.” Out of sight, for the moment. As long as Cory’s group didn’t make a scene.

“Well,” he said, dark eyes searching mine, “you really should’ve led with that.” He used his left hand to wipe away a raindrop that may or may not have existed on the side of my face, his thumb rough and familiar. “You take care now, Abby.”

Thank you, I mouthed, though I wasn’t sure he could see.

“Folks,” he said as he walked back, “there’ve been some flash flood warnings coming through. I think we’d better finish this up over a drink or two.”

He looked back once, used his fingers to tip the hood of his raincoat my way, like he was someone from another time.

I’d met Cory at the Last Stop myself almost ten years ago now. Before I knew he was the tavern owners’ son. A permanent, reliable fixture of town, whether you wanted him there or not. Ten years, and he still had that charisma, a fearlessness, the promise of secrets.

There were certain things about Cory that were still appealing, just as there were things about the inn that were not. It’s all in what you chose to focus your energy on, what you wanted to see. The flattering slant of the angle. The play of shadows. What you could get people to notice. What you could convince the majority of them to believe.

GEORGIA WAS GONE BY the time I returned, the office locked up, the registration area secured. She preferred morning shifts— handling breakfast instead of happy hour; checking guests out, instead of in. But she’d finished most of the evening routine for me. Like a fair trade for me dealing with Cory.

Celeste wouldn’t have hired Georgia on her own. Are we sure about her? she’d asked more than once. Celeste didn’t want people who seemed like they couldn’t do the hard things, and Georgia sure didn’t look it when she arrived. She’d come to the mountains to hike a stretch of the Appalachian in the second summer of the pandemic, but five days in, she left the group she’d been with, hiked herself down that access trail, and threw her pack on the floor of the lobby, coated in dirt and fatigue, like she’d wanted any excuse to get out and misjudged herself; like she’d reassessed her life and was out to make a change, before realizing that wasn’t the change she was looking for. “This isn’t me. I’m out,” she’d said before slapping a thick credit card on top of the registration desk.

I had imagined hard ground and poor packing; a man she was trying to impress, who was not impressed with her; I had imagined her waking up that morning, staring at the top of her tent, or the burned-out remnants of a campfire, or the heavy pack and the trail disappearing into the distance—and bailing.

It had seemed, from the way she had arrived, that she could not, in fact, do the hard things. But Celeste had been looking for more help so she could take a step back. And I thought I saw something in Georgia, something I recognized. So when Georgia extended her stay, asking around about jobs, I jumped.

A year later, for all our differences, I was glad to have her. The guests connected with her, and she was easy to work with, easy to live with. She might not have needed the money (a warning from Celeste, after she saw the car she’d returned with), but she did need something—and whatever it was, it kept her here, kept her loyal.

I lifted the phone from the cradle, pressed the power button, and listened to the soft familiar hum of the dial tone. See? Everything’s okay. Some line must have come down in town, and now it was back; and Trey West would spend a night in the place his brother was last seen, and come to terms with something, then head out in the morning; the storm would pass and tomorrow the mountain sun would creep across the sky, drying the earth in steady patches.

By tomorrow evening, all evidence of this would have disappeared, as so often happened here.

I left the phone on top of the desk, angled toward the lobby, and placed the sign beside it, designating my apartment number as the line to call for assistance. I checked the office locks one last time and peered around the common area, making sure everything was as it should be. Last, I hit the light switch hidden behind the registration area that turned off the upper lights, leaving only the soft glow of the gas lanterns in my wake.

Then I walked down the main hall, passing the series of framed black-and-white photographs showing the construction of the inn. First, Celeste and her late husband, Vincent, both with windswept hair: Vincent, with a strong jaw and chiseled face, smile turned toward her, sleeves of a button-down rolled up, like he’d just come from the office; Celeste with her head tipped back, wide smile, like she’d been starting to laugh. She must’ve been close to my age then. Both of them were standing beside the lumber that would one day become the dome of the lobby. The next pictures captured the various stages of the build, the main structure in skeleton form, all wood beams and open air, so that now, standing in this hall, I could almost smell the raw lumber under the drywall and paint.

Near the end of the hall, I pressed my thumb to a nail hole that still needed repair, visible under a patch of paint that hadn’t been spackled first. No one here visiting would notice, probably. But it was our job to find the imperfections and correct them, even in the rustic allure. The only flaws here were deliberate and curated. But there was never any time for a complete job until the off-season. Anytime I got started with a paint touch-up, I only noticed the borders where the color didn’t blend right, older sections that had faded or dulled from sunlight and time. The full repaint would have to wait for the string of winter days in January when we shut the inn for all the work we’d been putting off throughout the year.

I used my badge to unlock the nondescript door just before the back exit. Inside, the steps led down to the lower level, for employees, where we stopped pretending. Here, the doors had regular keys, regular locks—nothing that could be overridden with an electronic card. Along the hallway, scuff marks marred the walls, from furniture and supply deliveries, year after year.

Down the hall, I could hear music coming from Georgia’s apartment. She kept the radio on whenever she was in, even when she was sleeping, as if to confirm that she was there. As if she had listened to Cory’s talk one too many times, had started to believe the rumors herself—that an unknown danger could approach from the woods at any time.

My apartment was just past Georgia’s. I let myself in and locked up behind me. The noise from her room fell to silence. The walls on the lower level were built thick, for structure and support, and noise didn’t carry like it did out in the halls. Georgia and I each had a one-bedroom unit with a kitchenette and bathroom off a small all-purpose living space—the mirror image of each other’s.

Without turning on the light, I dropped my keys on the laminate counter, stepped out of my damp shoes, peeled off my socks. I removed the pins from my bun as I crossed the room, worked my fingers through the deep brown layers, feeling them slowly unspool.

The inn was built into a slope, so that our rooms on the lower level actually looked out onto the mountain, too, tucked into the side of the incline. Personally, I believed these were the best views, because you could see near and far equally—the blades of grass just on the other side of the glass, an animal tracking by, leaves falling over the sill; and the mountains in the distance, seeming even more massive, given the lower perspective.

My living room curtains remained closed, since guests sometimes explored the grounds directly outside. But my bedroom had a view that remained unobstructed and uncovered at all times. Upper windows that slanted outward, halfway to being skylights, giving way to a rocky overlook below, difficult to reach from the outside.

When I’d first arrived, I used to jolt alert in the night, listening for whatever had startled me, before realizing it must’ve been the silence itself. And I’d wake each morning disoriented by the perspective, taking a moment to recenter myself, remember where I was.

People seemed to think this place would settle into me immediately, that it was in my bones, somehow, as Celeste’s niece, even if we weren’t related by blood. But it had happened gradually, in a way that caught me by surprise. Ten years later, and it held the familiar comfort of home: It was private and perfect and mine.

I felt my way in the dark, pulling my pajamas from the drawer underneath my bed, brushing my teeth by the glow of the bathroom night-light, slipping into the familiar sheets.