Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

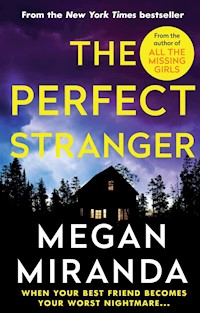

What happens when your best friend becomes your worst nightmare... Having reached a dead end in Boston, failed journalist Leah Stevens needs a change. When she runs into an old friend, Emmy Grey, who is moving to rural Pennsylvania, Leah decides to join her. But their fresh start is quickly threatened when a woman with an eerie resemblance to Leah is assaulted by the lake, and Emmy disappears days later. Determined to find Emmy, Leah helps Detective Kyle Donovan to investigate her friend's life for clues. But with no friends, family or digital footprint, the police begin to suspect that there is no Emmy Grey. Forced to question her version of reality and to save herself, Leah must uncover the truth - no matter how dark or terrible it may be...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 454

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE

PERFECT

STRANGER

ALSO BY MEGAN MIRANDA

All the Missing Girls

The Safest Lies

Soulprint

Vengeance

Hysteria

Fracture

First published in the United States in 2017 by Simon&Schuster, New York.

First published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2018 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Megan Miranda, 2017

The moral right of Megan Miranda to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 288 3E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 289 0

Printed in Great Britain.

CorvusAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondon WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For Luis

PROLOGUE

The cat under the front porch was at it again. Scratching at the slab of wood that echoed through the hardwood floors of my bedroom. Sharpening its claws, marking its territory— relentless in the dead of night.

I sat on the edge of the bed, stomped my feet on the wood, thought, Please let me sleep, which had become my repeated plea to all things living and nonliving out here, whatever piece of nature was at work each particular night.

The scratching stopped, and I eased back under the sheets.

Other sounds, more familiar now: the creak of the old mattress, crickets, a howl as the wind funneled through the valley. All of it orienting me to my new life—the bed I slept in, the valley I lived in, a whisper in the night: You are here.

I had been raised and built for city life, had grown accustomed to the sound of people on the street below, the car horns, the train running on the track until midnight. Had come to expect footsteps overhead, doors slamming shut, water in the pipes running through my walls. I could sleep through all of it.

The silence in this house, at times, was unsettling. But it was better than the animals.

Emmy, I could get used to. She slipped right in, the sputtering engine of her car in the driveway a comfort, her footsteps in the hallway lulling me to sleep. But the cat, the crickets, the owls, and the coyote—these took time.

Four months, and it was finally shifting, like the season.

___

WE HAD ARRIVED IN the summer—Emmy first; me, a few weeks later. We slept with our doors closed and the air turned on high, directly across the hall from each other. Back in July, when I first heard the cry in the middle of the night, I bolted upright in bed and thought, Emmy.

It was a muffled, low moan, like something was dying, and my mind was already filling in the blanks: Emmy struggling, grasping at her throat, or keeled over on the dusty floor. I’d raced across the hall and had my hand on her doorknob (locked) when she’d torn it open, staring back at me with wide eyes. She looked for a moment like she had when we’d first met, both of us barely out of school. But that was just the dark playing tricks on me.

“Did you hear that?” she’d whispered.

“I thought it was you.”

Her fingers circled my wrist, and the moonlight from the uncovered windows illuminated the whites of her eyes.

“What was it?” I asked. Emmy had lived in the wild, had spent years in the Peace Corps, had grown accustomed to the unfamiliar.

Another cry, and Emmy jumped—the sound had been directly below us. “I don’t know.”

She was roughly my size but skinnier. Eight years earlier, it had been the other way around, but she’d lost the curves and give in the years since she’d been gone. I felt I needed to be the one to protect her now. To shield her from the danger, because there was nothing to Emmy these days but sharp angles and pale skin.

But she moved first, noiselessly walking down the hall, her heels barely making contact with the floor. I followed, keeping my steps light, my breathing shallow.

I put my hand on the phone, which was corded and hooked to the kitchen wall, just in case. But Emmy had other plans. She grabbed a flashlight from the kitchen drawer, slid the front doors slowly open, and stepped out onto the wooden porch. The moonlight softened her, the breeze moving her dark hair. She arced the light across the tree line and started down the steps.

“Emmy, wait,” I’d said, but she’d eased herself onto her stomach in the dirt, ignoring me. She shone the light under the porch, and something cried again. I gripped the wooden railing as Emmy rolled onto her back, faintly shaking with laughter before it made its way from her gut, tearing through the night sky.

A hiss, a streak of fur darting from under the house straight into the woods, and another following behind. Emmy pushed herself to sitting, her shoulders still shaking.

“We’re living on top of a cat brothel,” she’d said.

The smile caught on my lips, a stark relief. “No wonder the price was so good,” I’d said.

Her laughter slowly died, something else pulling her focus. “Oh, look,” she’d said, a skinny arm pointing to the sky behind me.

A full moon. No, a supermoon. That’s what it was called. Yellow and too close, like it could affect the pull of gravity. Make us go mad. Make cats go crazy.

“We can put up cinder blocks,” I’d said, “to keep out the animals.”

“Right,” she’d said.

But, of course, we never did.

___

EMMY LIKED THE IDEA of the cats. Emmy liked the idea of old wood cabins and a porch with rockers; also: vodka, throwing darts at maps while drinking vodka, fate.

She was big on that last one.

It’s why she was so sure moving here together was the right thing to do, no second thoughts or second guesses. Fate leading us back together, our paths intersecting in a poorly lit barroom eight years since the last time we’d seen each other. “It’s a sign,” she’d said, and since I’d been drunk it made perfect sense, my thoughts slurring together with hers, wires crossing.

The cats were probably a sign, too—of what, I wasn’t sure. But also: the supermoon, the fireflies flashing in time to her laughter, the air thick with humidity, as if it were engulfing us.

Any time we’d hear a noise after that, any time I’d jolt alert from the worn brown sofa or from my seat at the vinyl kitchen table, Emmy would shrug and say, “Just the cats, Leah.”

But for weeks, I dreamed of bigger things living underneath us. Took the steps in one big leap when I left each day, like a kid. Pictured things coiled up or crouched down in the dark, in the dirt, nothing but yellow eyes staring back. Snakes. Raccoons. Stray and rabid dogs.

Just yesterday one of the other teachers said there was a bear in his yard. Just that: a bear in his yard. Like it was a thing one might or might not notice in passing. Graffiti on the overpass, a burntout streetlight. Just a bear.

“Don’t like bears, Ms. Stevens?” he’d said, toothy grin. He was older and soft, the skin around his wedding band ballooning from either side in protest, taught history and seemed to prefer it to reality.

“Who likes bears?” I’d said, trying to skirt him in the hall.

“You should probably like bears if you’re moving to bear country.” His voice was louder than necessary. “This is their home you all keep building right up on. Where else should they be?”

The neighbor’s dog started barking, and I stared at the gap between the window curtains, waiting for the first signs of light.

On mornings like this, despite my initial hope—the scent of nature, the charm of wood cabins with rockers, the promise of a fresh start—I still craved the city. Craved it like the coffee hitting my bloodstream in the morning, the chase of a story, the high of my name in print.

When I first arrived in the summer, there had been a period of long calm when the stretch of days welcomed me with a blissful absence of thought. When I’d woken in the morning and poured a cup of coffee and walked down the wooden front steps, feeling, for a moment, so close to the earth, in touch with some element I had previously been missing: my feet planted directly on the dirt surrounding our porch, slivers of grass poking up between my toes, as if the place itself were taking me in.

But other days, the calm could shift to an absence instead, and I’d feel something stir inside of me, like muscle memory.

Sometimes I dreamed that some nefarious hack had taken down the entire Internet, had wiped us all clean, and I could go back. Could start over. Be the Leah Stevens I had planned to be.

CHAPTER 1

Character, Emmy called it, the quirks that came with the house: the nonexistent water pressure in the shower; the illogical layout. From the front porch, our house had large sliding glass doors that led directly to the living room and kitchen, a hallway beyond with two bedrooms and a bathroom to share. The main door was at the other end of the hall and faced the woods, like the house had been laid down with the right dimensions but the wrong orientation.

Probably the nicest thing I can say about the house was that it’s mine. But even that’s not exactly true. It’s my name on the lease, my food in the refrigerator, my glass cleanser that wipes the pollen residue from the sliding glass doors.

The house still belongs to someone else, though. The furniture, too. I didn’t bring much with me when I left my last place. Wasn’t much, once I got down to it, that was mine to take from the one-bedroom in the Prudential Center of Boston. Bar stools that wouldn’t fit under a standard table. Two dressers, a couch, and a bed, which would cost more to move than to replace.

Sometimes I wondered if it was just my mother’s words in my head, making me see this place, and my choice to be here, as something less than.

Before leaving Boston, I’d tried to spin the story for my mother, slanting this major life change as an active decision, opting to appeal to her sense of charity and decency—both for my benefit and for hers. I once heard her introduce me and my sister to her friends: “Rebecca helps the ones who can be saved, and Leah gives a voice to those who cannot.” So I imagined how she might frame this for her friends: My daughter is taking a sabbatical. To help children in need. If anyone could sell it, she could.

I made it seem like my idea to begin with, not that I had latched myself on to someone else’s plan because I had nowhere else to go. Not because the longer I stood still, the more I felt the net closing in.

Emmy and I had already sent in our deposit, and I’d been floating through the weeks, imagining this new version of the world waiting for me. But even then, I’d steeled myself for the call. Timed it so I knew my mother would be on her way to her standing coffee date with The Girls. Practiced my narrative, preemptively preparing counterpoints: I quit my job, and I’m leaving Boston. I’m going to teach high school, already have a position lined up. Western Pennsylvania. You know there are whole areas of the country right here in America that are in need, right? No, I won’t be alone. Remember Emmy? My roommate while I was interning after college? She’s coming with me.

The first thing my mother said was: “I don’t remember any Emmy.” As if this were the most important fact. But that was how she worked, picking at the details until the foundation finally gave, from nowhere. And yet her method of inquiry was also how we knew we had a secure base, that we weren’t basing our plans on a dream that would inevitably crumble under pressure.

I moved the phone to my other shoulder. “I lived with her after college.”

A pause, but I could hear her thoughts in the silence: You mean after you didn’t get the job you thought you’d have after graduation, took an unpaid internship instead, and had no place to live?

“I thought you were staying with . . . what was her name again? The girl with the red hair? Your roommate from college?”

“Paige,” I said, picturing not only her but Aaron, as I always did. “And that was just for a little while.”

“I see,” she said slowly.

“I’m not asking for your permission, Ma.”

Except I kind of was. She knew it. I knew it.

“Come home, Leah. Come home and let’s talk about it.”

Her guidance had kept my sister and me on a high-achieving track since middle school. She had used her own missteps in life to protect us. She had raised two independently successful daughters. A status I now seemed to be putting in jeopardy.

“So, what,” she said, changing the angle of approach, “you just walked in one day and quit?”

“Yes,” I said.

“And you’re doing this why?”

I closed my eyes and imagined for a moment that we were different people who could say things like Because I’m in trouble, so much trouble, before straightening my spine and giving her my speech. “Because I want to make a difference. Not just take facts and report them. I’m not doing anything at the paper but stroking my own ego. There’s a shortage of teachers, Mom. I could really make an impact.”

“Yes, but in western Pennsylvania?”

The way she said it told me everything I needed to know. When Emmy suggested it, western Pennsylvania seemed like a different version of the world I knew, with a different version of myself—which, at the time, was exactly what I needed. But my mother’s world was in the shape of a horseshoe. It stretched from New York City to Boston, swooping up all of Massachusetts inside the arch (but bypassing Connecticut entirely). She was the epicenter in western Massachusetts, and she’d successfully sent a daughter to the edge of each arch, and the world was right and complete. Any place else, in contrast, would be seen as a varying degree of failure.

My family was really only one generation out from a life that looked like this: a rental house with shitty plumbing, a roommate out of necessity, a town with a forgettable name, a job but no career. When my father left us, I wasn’t really old enough to appreciate the impact. But I knew there existed a time when we were unprepared and at the whim of the generosity of those around us. Those were the limbo years—the ones she never talked about, a time she now pretends never existed.

To her, this probably sounded a lot like sliding backward.

“Great teachers are needed everywhere,” I said.

She paused, then seemed to concede with a slow and drawnout “Yes.”

I hung up, vindicated, then felt the twinge. She was not conceding. Great teachers are needed everywhere, yes, but you are not that.

She didn’t mean it as an insult, exactly. My sister and I were both valedictorians, both National Merit Scholars, both early admissions to the college of our respective choice. It wasn’t unreasonable that she would question this decision—especially coming out of thin air.

I quit, I had told her. This was not a lie, but a technicality—the truth being that it was the safest option, for both the paper and me. The truth was, I had no job in the only thing I’d trained in, no foreseeable one, and no chance of one. The truth was I was glad she had given me the blandest name, the type of name I’d hated growing up. A girl who could blend in and never stand out. A name in a roster anywhere.

___

EMMY’S CAR STILL WASN’T back when I was ready to leave for school. This was not too unusual. She worked the night shift, and she’d been seeing some guy named Jim—who sounded, on the phone, like he had smoke perpetually coating his lungs. I thought he wasn’t nearly good enough for Emmy; that she was sliding backward in some intangible way, like me. But I cut her some slack because I understood how it could be out here, how the calm could instead feel like an absence—and that sometimes you just wanted someone to see you.

Other than weekends, we could miss each other for days at a time. But it was Thursday, and I needed to pay the rent. She usually left me money on the table, underneath the painted stone garden gnome that she’d found and used as a centerpiece. I lifted the gnome by his red hat just to double-check, revealing nothing but a few stray crumbs.

Her lateness on the rent was also not too unusual.

I left her a sticky note beside the corded phone, our designated spot. I wrote RENT DUE in large print, stuck it on the wood-paneled wall. She’d taken all the other notes from earlier in the week—the SEE ELECTRIC BILL, the MICROWAVE BROKEN, the MICROWAVE FIXED.

I opened the sliding doors, hit the lights at the entrance, rummaged in my bag for my car keys—and realized I’d forgotten my cell. A gust of wind came in through the door as I turned around, and I watched the yellow slip of paper—RENT DUE—flutter down and slip behind the wood stand where we stacked the mail.

I crouched down and saw the accumulated mess underneath. A pile of sticky notes. CALL JIM right side up but half covered by another square. A few others, facedown. Not taken by Emmy after all but lost between the wall and the furniture during the passing weeks.

Emmy didn’t have a cell because her old one was still with her ex, on his phone plan, and she didn’t want an easy way for him to trace her. The idea of not owning a cell phone left me feeling almost naked, but she said it was nice not to be at anyone’s beck and call. It had seemed so Emmy at the time—quirky and endearing— but now seemed both irrational and selfish.

I left the notes on the kitchen table instead. Propped them up against the garden gnome. Tried to think of how many days it had been since I’d last seen her.

I added another note: CALL ME.

Decided to throw out the rest, so it wouldn’t get lost in the shuffle.

CHAPTER 2

There was a roadblock set up on the way to school, at the end of the main road that cut back to the lake. A car flashing red and blue, an officer directing traffic past the turn. I eased my foot off the gas, felt my heart do a familiar flip.

As a reporter, I had grown accustomed to certain signs of a trauma scene, besides the emergency vehicles: the barricading of an area, the set of onlookers’ jaws, strangers standing too close together with their heads tipped down in respect. But more than that, there’s a crackle in the air. Something you can feel, like static electricity.

It drew me, that crackle.

Drive on past, Leah. Keep going.

But this was only a couple miles from our house, and Emmy hadn’t gotten home yet. If she’d been in an accident, would they know whom to call? How to reach me? Could she be at a hospital right now, all alone?

I passed the officer in the street and pulled my car over at the next turn, left it unlocked in the parking lot of the unfinished lake clubhouse in my rush, and backtracked toward the roadblock. As I walked, I kept to the trees, staying out of the traffic cop’s way so he couldn’t turn me back.

The land sloped down where the water line met mud and tall grass. At the bottom of the incline, I could see a handful of people standing stock-still. They were all focused on a point in the grass beyond. No car, though. No accident.

I slid down the embankment, mud caking my shoes, moving faster.

The scene came into focus, despite the adrenaline, the undercurrent of dread, as I pictured all the things that could’ve happened here.

I’d had to practice detachment early on, when the shock of blood was too sharp, when I felt too deeply, when I saw a thousand other possibilities in the slack face of a stranger. Now I couldn’t shake it—it was one of my top skills.

It was the only way to survive in real crime: the raw blood and bone, the psychology of violence. But too much emotion in an article and all a reader sees is you. You need to be invisible. You need to be the eyes and ears, the mechanism of the story. The facts, the terrible, horrible, blistering facts, have to become compartmentalized. And then you have to keep moving, on to the next, before it all catches up with you.

It was muscle memory now. Emmy became fragments, a list of facts, as I made my way through the tall grass: four years in the Peace Corps; moved here over the summer to escape a relationship turned sour; worked nights at a motel lobby, occasional days cleaning houses. Unmarried female, five-five, slight build, dark hair cut blunt to her collarbone.

Light slanted through the trees, reflecting off the still surface of the water beyond. The police were picking their way through the vegetation in the distance, but a single officer stood nearby with his back to the group of spectators, keeping them from getting any closer.

I made my way to the edge of the group. Nobody even looked. The woman beside me wore a bathrobe and slippers, her graying hair escaping the clip holding it away from her face.

I followed their singular, focused gaze—a smear of dried blood in the weeds beside the cop, marked off with an orange flag. The gnats settling over it in the morning light. A circle of cones beyond, nothing but flattened empty space inside.

“What’s happening?” I asked, surprised by the shake in my own voice. The woman barely looked at me, arms still crossed, fingers digging in to her skin.

Interview people after a tragedy and they say: It all happened so fast.

They say: It’s all a big blur.

They pick pieces, let us fill in the gaps. They forget. They misremember. If you get to them soon enough, there’s a tremble to them still.

These people were like that now. Holding on to their elbows, their arms folded up into their stomachs.

But put me on a scene and everything slows, simmers, pops. I will remember the gnats over the weeds. The spot of blood. The downtrodden grass. Mostly, it’s the people I see.

“Bethany Jarvitz,” she said, and the tightness in my chest subsided. Not Emmy, then. Not Emmy. “Someone hit her pretty good, left her here.”

I nodded, pretending I knew who that was.

“Some kids found her while they were playing at the bus stop.” She nodded toward the road I’d just come from. No kids playing any longer. “If they hadn’t . . .” She pressed her lips together, the color draining. “She lives alone. How long until someone noticed she was missing?” And then the shudder. “There was just so much blood.” She looked down at her slippers, and I did the same. The edges stained rust brown, as if she had walked right through it.

I looked away, back toward the road. Heard the static of a radio, the voice of a cop issuing orders. This had nothing to do with Emmy or with me. I had to leave before I became a part of it, a member of the crowd the police would inevitably take a closer look at. My name tied to a string of events that I was desperate to leave behind. A restraining order, the threat of a lawsuit, my boss’s voice dropping low as the color drained from his neck: My God, Leah, what did you do?

I took a step back. Another. Turned to make my way back to my car, embarrassed by the mud on my shoes.

Halfway to my car, I heard a rustle behind me. I spun around, nerves on high alert—and caught a faint whiff of sweat.

A bird took flight, its wings beating in the silence, but I saw nothing else.

I thought of the noise in the dead of night. The dog barking. The timing.

An animal, Leah.

A bear.

Just the cats.

___

BY THE TIME I made it to school, I was bordering on late. School hadn’t started yet, but I was supposed to arrive before the warning bell. There was a backlog of student cars lined up at the main entrance, so I sneaked in through the bus lot (frowned upon but not against the rules), parked in a faculty spot behind my wing, and used a key to let myself in through the fire entrance (also frowned upon, also not against the rules).

The teachers were clustered just inside the classroom doorways, whispering. They must’ve gotten wind of the woman down by the lake. This wasn’t like life in a city, where there was a new violent crime each day, where the sirens were background noise and mere proximity meant nothing. I wouldn’t have been able to get a decent story about a woman found on the shore of a lake in the paper there—not one who’d lived.

CHAPTER 3

It wasn’t just the teachers.

The entire school was buzzing. It carried from the halls, rolled in with the students, grew louder and more urgent as they twisted in their seats. A hand over a mouth, Oh my God. A gasp, a head whipping from one person to the next. They were surely talking about the woman found down by the lake.

So it would be one of those days. Impossible to get first period in order.

The school would get like this sometimes, with the buzzing, but it was like listening to a conversation in an unknown language. The gossip written in secret shorthand, a scrawl I’d long since forgotten.

I’d begun to think the disconnect stemmed from more than just age. That they were a species in transition: coming in as kids, voices breaking, angles sharpening, and leaving as something different altogether. Curves and muscle and the unfamiliar force behind both; the other parts of them desperately trying to play catch-up.

Behave, we’d tell them. And they’d sit at their desks, hunkered down and waiting, a toe from somewhere in the room tapping against the floor in a manic rhythm. They’d bolt from their seats at the end-of-class bell and dash for the door, taking off as if the wild had called to them, the room reeking of mint and musk long after they were gone.

I didn’t understand how anyone truly expected me to accomplish anything here, except in appearances. This was nothing but a temporary holding cell.

Had I been like this once upon a time? I didn’t think so. I couldn’t really remember. Even back then, I think I had narrowed my sights on a goal and homed in.

The bell rang for the start of class, but the buzzing continued.

I pulled the stack of graded reading responses from my bag, and I heard it—

Arrested.

My stomach clenched. The word razor-sharp, a constant threat. Always there, the slimmest possibility: my ex, Noah, warning me to be careful with that article—I thought that was exactly what I was doing, I truly did.

Back when I was in college, I remembered a professor’s eyes fixing on mine in the middle of his lecture, as if he could sense something in me even then, as he explained that in journalism, a lie becomes libel.

But it was more than that, truly. More than just a legal term, in journalism, the lie is a breach of the holiest commandment.

Get out now, my boss had said. And hope the story dies.

I’d done just that—putting an entire mountain range between us in the process. But in the information age, distance meant nothing. I’d thought I’d escaped it, but maybe I hadn’t.

No. I was being irrational. A woman had been found beaten just a few hours earlier; that’s what this was about.

I weaved between desks, placing their essays facedown in front of them. Leaning closer, straining for information. An old habit.

Connor Evans’s big wide eyes were fixed on me, and my shoulders tensed. Someone in this room?

I took a tally of the class—who was missing? JT, but JT was never on time.

But there, an empty seat, third row, desk beside the window: Theo Burton.

He’d turned in his journal a few weeks earlier with a new freewrite that made my skin crawl—but it was fiction, and I’d said anything. Still, he wrote with an authority and confidence greater than his imagination. Too close to something real. I closed my eyes, his words dancing across my mind:

The boy sees her and he knows what she has done.

The boy imagines twisted limbs and the color red.

If Theo had done something, if that entry had been a warning—God, the liability.

I could come up with a story for myself, a cover: I didn’t read it closely. It was a participation grade. I didn’t know.

But then Theo Burton walked through the door, and the tension drained from my shoulders. On the way to his desk, he stood in front of the class for a beat. “The cops are crawling the front office,” he said, like he was in charge. His collar popped up, his shoes unscuffed. Too civilized, Theo Burton in real life.

If this were my second-period class, they’d tell me what had happened, unprompted. They were all freshmen and treated me like a confidante. Third period would welcome any excuse to veer off-topic, so I could ask them without feeling at a disadvantage. But my first period had decided at the start of the year to rebel, and I’d never recovered. If I thought they were either bright enough or organized enough, I would’ve given them credit for planning it together. A coordinated attack.

But the mistake had been of my own making, as was the story of my current life. My first day of teaching, I’d introduced myself and told them I had just moved from Boston. I thought kids in a place like this—living in a town on the downswing suddenly given a jolt of new life—might be impressed. I thought I had them all figured out.

A girl in the back row had yawned, so I’d added, I worked as a journalist, thinking that might lend some authority. And that girl who’d been yawning, her head snapped up, and she grinned like a cat with a canary dangling between her front teeth. Her name, I soon learned, was Izzy Marone, and she said, “Is this your first year teaching?”

I had been here three minutes and I’d already made a mistake. There was no reason for them to think I was a new teacher at thirty. That I was starting my life over, having failed at the first half.

There were four ninety-minute blocks in the school day, but first period still felt twice as long as the rest.

Izzy Marone was currently holding court around her desk, chairs pulled closer, boys leaning nearer. Theo Burton reached across the gap and placed his fingers on the ridge of her cheekbone, speaking directly into her ear. Her face was grave.

I decided to try for Molly Laughlin, who was on the outskirts, both physically and metaphorically, hoping everyone else was too wrapped up in the whispers to notice. “What happened?” I asked. I prided myself on finding sources and getting them to talk, and she was an easy pick. I think I got her with the shock of it—that I’d asked her outright.

She opened her mouth as my class speaker crackled on.

“Ms. Stevens?” The assistant principal’s voice silenced the room.

“Yes, Mr. Sheldon?” I responded.

It had taken me a few weeks to catch on to this quirk, that teachers spoke to each other like this, whether it was over speakers where students could hear or out in the halls, alone. I couldn’t get used to adults going by last names like this, all antiquated formality.

“You’re needed for a moment in the office.” Mitch Sheldon’s voice echoed through the room.

I became aware of the stillness and the silence behind me, the twenty-four pairs of ears, listening, wanting.

The police were in the office, and they needed me.

I raised my hand to my mouth, was surprised to notice my fingers were trembling. I went for my purse in the locked desk drawer at the side of the room, taking my time. Realizing they all knew something I didn’t.

The lock stuck twice before the drawer slid open.

Izzy turned to me, frowned at my shaking hands. “You heard?” she asked.

“Heard what?” I said.

For all the pretense of gravity she was trying to interject, it was obvious from the quirk of her lips that she was about to take great pleasure in telling me this. As if she knew I had no idea. I steeled myself once more.

“Coach Cobb was just arrested for assault,” she said.

Oh. Shit.

She got me.

CHAPTER 4

Davis Cobb was the reason I’d begun leaving my phone on silent at night. I ignored his calls every time they came through—always after eleven P.M., always after I assumed he’d been down at the bar and was walking back home. Always the same thing, anyway.

Davis Cobb owned the Laundromat in town and moonlighted as the school’s basketball coach, but I didn’t know either of those things when I first met him while filling out paperwork down at the county office.

I’d thought he was a teacher. Everyone seemed to know him. Everyone seemed to like him. They said, Hey, Davis, have you met Leah? You’ll be working together come fall, and he’d smiled.

He’d offered a drink at the nearest bar—he had a ring on his finger, it was the middle of the day, You can follow me in your car. It seemed like a friendly welcome-to-town offer. He seemed like a lot of things—until he showed up at my door one night.

I passed Kate (Ms. Turner) on her way down the hall in the opposite direction. Her brow was furrowed, and at first she didn’t notice me. But then she stopped, grabbed my arm as we brushed by each other, passed a quick secret: “They want to know if Davis Cobb has ever done anything inappropriate toward us. It was quick. Really quick.”

My stomach twisted, thinking of what evidence they might already have that might drag me into this. The recent calls. His phone records. If that was the reason the overhead speaker had crackled my name.

“You okay?” she asked, as if she could read something in my silence. After the last few months of working across the hall from me, she had become a friendly face throughout the chaos of the day. Now I worried she could see even more.

“This whole thing is weird,” I said, trying to channel her same perplexed expression. “Thanks for the heads-up.”

Inside the front office area, Mitch Sheldon was posted outside the conference room door, arms crossed like a security guard, feet planted firmly apart, even in khaki pants, even in men’s loafers. He dropped his arms when he saw me approaching. Mitch was the closest thing I had to a mentor here, and a friend, but I didn’t know what to make of his expression just yet.

The door was open behind him, and I counted at least two men in dark jackets at the oval table, drinking coffee from Styrofoam cups. “What happened?” I asked.

“Jesus Christ,” Mitch said, lowering his voice and leaning closer. “They picked up Davis Cobb for assault this morning. First I’m hearing of it, too. The calls from the media and parents started as soon as I got here.”

The reception area with the glass windows that faced the school entrance was crawling with cops, like Theo had said. But there were no other teachers roaming the area up front, or in the hallway with the offices behind reception, where we now stood. Just Mitch, just me.

Mitch nodded toward the door. “They asked for you.” He swallowed. “They’re interviewing all the women, but they asked for you by name.”

A question, bordering on an accusation. “Thanks, Mitch.”

I shut the door behind me as I entered the room. I had been wrong—there were three people in the room. Two men in attire so similar it must’ve been department protocol, and a woman in plainclothes.

The man closest to me stood and did a double take. “Leah Stevens?” he asked, his badge visible at his belt.

My shoulders stiffened in response. “Yes,” I said, arms still at my sides, exposed and waiting, feeling as though I were on display.

He extended his hand. “Detective Kyle Donovan,” he said. He was the younger of the two but more polished, more mature in stature somehow. Made me think he was the one in charge, regardless of seniority. Maybe it was just that he was fit and held eye contact, and I was biased. So I have a type.

I reached out a hand to shake his, then leaned across the table, repeating the motion with the older man. “Detective Clark Egan,” he said. He had graying sideburns, a softer build, duller eyes. He tilted his head to the side, then shared a look with Detective Donovan.

“Allison Conway.” Role still undetermined, business suit, blond hair falling in waves to her shoulders.

“Thanks for agreeing to see us,” Donovan said, as if I had the choice. He gestured toward the chair across from him.

“Of course,” I said, taking a seat and trying to get a read on the situation. “What’s this about?”

“We have just a few questions for you. Davis Cobb. You know him?”

“Sure,” I said, crossing my legs, trying to appear more at ease.

“How long have you known him?” he continued.

“I met him in July, down at the county office, when I registered with the district.” Fingerprints, drug test, background check. Teachers and cops, the last line of unsullied professions. They check criminal records but not the civil suits. Almosts don’t count. Gut feelings count even less. There were so many cracks you could slip through. So much within that could not be revealed by a history of recorded offenses and intoxicants.

Davis Cobb had managed.

“You became friends?” Detective Donovan asked.

“Not really.” I tried not to fidget, with moderate success.

“Has he ever contacted you directly? Called you up?”

I cleared my throat. And there it was. The evidence they had, the reason they pulled me from class. Careful, Leah.

“Yes.”

Detective Donovan looked up, my answer a spark. “Was it welcome? Had you given him your number?”

“The school has a directory. We all have access to the information.” That and our addresses, I had learned.

“When was the last time he called you?” Detective Egan cut in, getting right to the point.

I assumed if they were asking, they already knew and were just waiting on me to confirm, prove myself trustworthy. “Last night,” I said.

Detective Donovan hadn’t taken his eyes off me, his pen hovering in the air, listening but not making any notes. “What did you speak about?” he asked.

“I didn’t,” I said. I pressed my lips together. “Voicemail.”

“What did he say?”

“I deleted it.” This had been Emmy’s idea. Frowning at the phone in my hand a few weeks ago, asking if it was that Cobb asshole again. After I’d nodded, she’d said, You know, you don’t have to listen to it. You can just delete them. It had felt like such a foreign idea at first, this casual disregard of information, but there was something inexplicably compelling about it, too—to pretend it never existed in the first place.

Detective Egan opened his mouth, but at this point, the woman—Allison Conway, role undetermined—cut him off. “Is this something that happens often?” she asked. From the cell phone records, they knew that it was.

“Yes,” I said. I folded my hands on the table. Changed my mind. Held them underneath.

Detective Donovan leaned forward, hands folded, voice dropping. “Why does Davis Cobb call you night after night, Ms. Stevens?”

“I have no idea, I don’t pick up.” Yes, it was a good idea to keep my hands under the table. I felt my knuckles blanching white in a fist.

“Why didn’t you pick up?” Donovan asked.

“Because he called me drunk night after night. Would you pick up?” It was a habit Cobb seemed to have grown fond of. Heavy breathing, the sounds of the night, of the breeze—back when I still used to listen to the messages, trying to decipher the details, as if knowledge alone were a way to fight back. It always left me vaguely unsettled instead. Like he wanted me to think he was on his way. That he was watching.

Mitch Sheldon was just outside the door, and I knew he was probably listening.

“What was the nature of your relationship?” Egan cut in again.

“He drunk-dialed me late at night, Detective, is the gist of our relationship.”

“Did he ever threaten you?” he asked.

“No.” Are you home alone, Leah? Do you ever wonder who else seesyou? His voice so quiet I had to press the phone to my ear just to hear it, wondering if he was coming closer as well, on the other side of the wall.

“Did his wife know?” he asked, implying something more.

I paused. “No, I think it’s safe to assume his wife didn’t know.”

___

LONG BEFORE THE CALLS, there had been the Saturday night, a car engine outside, smoother and quieter than Jim’s. Emmy sleeping, me reading a book in the living room. The footsteps on the front porch, and Davis Cobb’s image manifesting out of thin air, like a ghost. He knocked on the glass door, looking directly at me.

“Leah,” he’d said when I slid the door open a crack, like I had invited him. His breath was laced with liquor, and he leaned too close, the scent coming in with a gust of night air. I had to put up my hand to prevent him from sliding the door open all the way.

“Hey,” he’d said, “I thought we were friends.” Only that hadn’t been what he was implying at all.

“It’s late. You have the wrong idea,” I’d said, and there was this moment while I held my breath, waiting for the moment to flip one way or the other.

“You think you’re too good for us, Leah?”

I’d shaken my head. I didn’t. “You need to leave.”

A creak in the floor had sounded from somewhere behind me, deep in the shadows of the hall, and Davis finally backed away, into the night. I watched the darkness until I heard the rumble of his engine fading in the distance.

I’d turned around, and Emmy peered out from the shadow of her room, visible only now that he was gone. “Everything okay?” she’d asked.

“Just some guy from work. Davis Cobb. He’s leaving now.”

“He shouldn’t be driving,” she’d said.

“No,” I’d said, “he shouldn’t.”

___

IT WAS WARM IN the conference room. Egan shifted in his seat, whispered something to Conway, but Donovan was watching me closely.

“He hurt that woman? The one they’re all talking about— Bethany Jarvitz?” I asked, looking directly at Donovan.

“Would this surprise you?” he asked, and now I had everyone’s attention again.

I paused. There was a time in my life, from before I met Emmy, when I would’ve said yes. “No.”

There was something in his look that was close to compassion, and I wasn’t sure if I liked it. “Any reason you say this?” he asked.

Davis Cobb, married, respectable member of society, small-business owner, high school basketball coach. I had learned long ago, in a brutal jolt into reality, that none of this mattered. Nothing surprised me.

“Not particularly,” I said.

He leaned a little closer, let his eyes peruse me briefly and efficiently. “Do you know Bethany Jarvitz, Ms. Stevens?”

“No,” I said.

Detective Donovan slid a photo out of a folder, tapped the edge against the tabletop, like he was debating something. In the end, his decision tipped, and he let the photo fall, faceup. He twisted it around with the pads of his fingers until it was facing me.

“Oh.” The word escaped on an exhale—the reason for the double take, for the looks. It would seem that Davis Cobb, too, had a type, and it was this: brown hair and blue eyes, wide smile and narrow nose. Her skin was tanner, or maybe it was just from the time of year, and her hair was longer, and there was a slight gap between her two front teeth, but there were more similarities than differences. If I had these two students in my class, I’d have to make a mental note—Bethany needs braces—as a way to remember.

“She was found less than a mile from where you live, in the dark.”

In the dark, at first glance, we could be the same person.

Someone cracked their knuckles under the table. “We would like you to make a statement,” Egan said to me, gesturing to the woman beside him, and at this point, Allison Conway’s role became apparent. She was the one who would be taking the statement. She was a woman, a victim’s advocate, who would be gentle with the sensitive topic.

“No,” I said. I needed, more than anything, to stay out of things. To keep the fresh start, with my name a blank slate. I had to be more careful whom I confided in, to be sure whom I could trust.

Before I’d left Boston, before the shit had hit the fan, I’d been seeing Noah for nearly six months and had been friends with him for longer. We’d worked together at the same paper, and the competition had fueled us. But it had been a mistake, thinking we were the same underneath. It was Noah who had turned me in. It was Noah who had ruined my career. Though my guess is he’d say I’d done it to myself.

Becoming involved now could only disrupt the delicate balance I’d left in Boston. It was better for everyone if I disappeared, kept my name out of the press, out of anything that could make its way to law enforcement.

“It would help the case,” Donovan said, and Conway shot him a look.

“No,” I repeated.

“If Davis Cobb was stalking you,” she began. Her voice was soft and caring, and I could imagine that she would try to hold my hand if she were any closer. “It would help our case. It could help Bethany and you. It could keep others safe.”

“No comment,” I said, and she looked at me funny.

This was code for Back the fuck off. For You are not free to print my name. For Go find a different angle. But it didn’t seem to be translating here.

I pushed back my chair, and that seemed to get the message across just fine.

“Thank you, Ms. Stevens, for your time.” Kyle Donovan stood and handed me his card. From the way he was looking at me, once upon a time, I would have thought we’d work well together. I thought I would’ve enjoyed that.

I turned to go. Stopped at the door. “I hope she’s okay.”

___

I WAS RIGHT. MITCH had been waiting just outside the door. “Leah,” he said as I passed. Serious business, then, using my first name in school.

“I’ve got to get to class, Mitch,” I said. I kept moving, leaving through the back entrance beyond the offices that cut straight to the classroom wings.

The school was like a different beast when class was in session. A pencil dropped somewhere down the hall, rolling slowly along the floor. A toilet flushed. My steps echoed.

I walked back to class thinking I had somehow dodged a bullet. Until I took over for Kate Turner, who was seamlessly hopping between her classroom and mine, overseeing the busywork she’d assigned to my class. Okay? she mouthed. She must’ve stepped in when she realized my questioning was taking significantly longer than hers.

I nodded my thanks, feigned nonchalance. No problem.

Izzy Marone raised her hand after Kate left. The rest of the room remained silent and riveted.

“Yes, Izzy?” I heard the clock ticking behind me. An engine turning over outside the window. A bee tapping against the glass.

“We were wondering, Ms. Stevens, why’d they want to talk to you about Coach Cobb.”

And I realized I had escaped nothing.

“Get back to work,” I said. I felt all eyes on me. For once, I’d become as interesting to them as I’d always hoped to be. As worthy of their undivided attention and their awe.

I sat at my desk, opened my school email, deleted everything with one click of my mouse. Easier than filtering through for his messages, which were always the same thing, anyway. I was sure they still existed somewhere in the ether, but better to wipe it all from the surface.

The town was in flux, as I had been, and I’d felt an intangible camaraderie with the place when Emmy and I first arrived. The school was brand-new, a fresh coat of paint over everything, all the classrooms equipped with the latest technology. Our first day, during orientation, Kate had commented that it was like living in a dream compared to her previous school. Here, we would not have to share printers or sign up for the television a week in advance. It was a fresh start for everyone.

The population of the school was comprised of both old and new: the people who had lived here forever, generations gone back—former mining families, those who stayed through the economic downturn; and the new money who moved up with the tech data center, a promise of a second life breathed into the economy. I had envisioned becoming a part of this new second life along with the school, which had just been opened to accommodate the growing population. We were all in this together. Building ourselves back up, into something.

But it hadn’t been. The jobs weren’t for the people who’d been living there. The new facility brought with it new workers. Schools doubled in size, split and rezoned, lines were redrawn, teachers were needed. With my degree in journalism, and real-life experience, and desire to relocate to the middle of nowhere, I was needed.

Izzy Marone smacked her gum, mostly because she wasn’t supposed to chew gum, mostly because she knew nobody would stop her. She twirled a pencil, watching me closely.

Izzy belonged to the second group of new money. As if the monstrous house in the personality-devoid neighborhood and her status in the middle of nowhere were something to flaunt.

Sometimes it took nearly all of my willpower not to lean forward, take her by the shoulders, and whisper in her ear: You go to public school in the middle of fucking nowhere. You will become nonexistent if you try to take a step beyond the town line. You will not hack it anywhere else.

Well. I shouldn’t talk.

CHAPTER 5

Ileft school early on purpose. Fourth period was my free block, and although, technically, I was supposed to stay until at least fifteen minutes after dismissal, I figured no one would mention it today. Emmy still hadn’t called, and I wanted to catch her before she left for work. Something had wormed its way into the back of my head, unsettling, unshakable. I needed to see her.

Our home was a ranch on the outskirts of town. Emmy had fallen in love with this house before I made it down; she said it looked like one of those quaint grandparent houses, said we’d be like two old ladies and we’d get rockers for the porch and take up knitting. I saw it first through her eyes—something calm and idyllic, another version of Leah Stevens, a person I had yet to meet. When I came down in the summer, I fell in love with the house, too. It was surrounded by all greens and browns, the sound of birds singing, leaves swaying in the breeze. It was a small part of a larger landscape, and I felt part of something real for the first time. Something alive.