2,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Abela Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

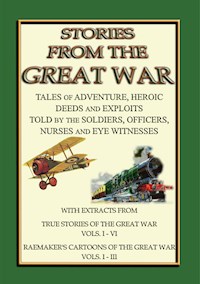

This book contains 18 true stories from soldiers about observations actions they were involved in during the Great War compiled from various sources by John Halsted, author and publisher. Here you will find stories like “The New St George”, “On the Anzac Trail”, "Todger Jones, V.C.” and the poignant, “Is that you mother” in which a German soldier was seen comforting a dying British Tommy, proving that even in the midst of such depravity there is yet some humanity left in the most hardened soldier.

From time-to-time soldiers escapades and actions, on both sides, were heroic and great. But it can be said that there was nothing “great” about being in the trenches during WWI.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

STORIESFROM

THE GREAT WAR

TALES of ADVENTURE—HEROIC DEEDS—EXPLOITSTOLD by the SOLDIERS, OFFICERS, NURSES,DIPLOMATS and EYE WITNESSESWith extracts from

True Stories of the Great War - Vols. I - VIRaemaker’s Cartoons of the Great War – Vols. I - III

Compiled by

John Halsted

Published by

Abela Publishing, London

[2016]

True Stories from the Great War

Typographical arrangement of this edition

© Abela Publishing 2016

This book may not be reproduced in its current format in any

manner in any media, or transmitted by any means whatsoever,

electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, or mechanical ( including

photocopy, file or video recording, internet web sites, blogs,

wikis, or any other information storage and retrieval system)

except as permitted by law without the prior written permission

of the publisher.

Abela Publishing

London

United Kingdom

2016

email:

Webmail:

www.AbelaPublishing.com

Acknowledgements

The Publisher acknowledges the work that

LOUIS RAEMAEKERS

and

J. MURRAY ALLISON

did

in compiling, editing and illustrating

Raemaeker’s Cartoons of the Great War Vols. I - III

in a time well before any electronic media was in use.

* * * * * * *

The Publisher also acknowledges the work that

FRANCIS TREVELYAN MILLER (Litt. D., LL.D.)

did in compiling and acting as Editor in Chief for

True Stories of the Great War Vols. I – VI

also in a time well before any electronic media was in use.

In memory of

Those who lost their lives in

The Dublin Uprising

of

Easter 1916

and the many, on all sides, who

made the ultimate sacrifice during

The Great War.

-------------------

Contents

The New St. George

Introductory

The Eyes of the Army

Turning Heavens Into Hell—Exploits Of The Canadian

Flying Corps

The British Commonwealth In Arms

On The Anzac Trail—With The Fighting Australasians

Tales Of German Air Raiders Over London And Paris

The Martyred Nurse

Last Hours Of Edith Cavell On Night Of Execution

Kultur Has Passed Here

"Flying For France"—Hero Tales Of Battles In The Air

Is It You, Mother?

Knights Of The Air—Frenchmen Who Defy Death

The Promise

"Todger" Jones, V. C.

The Berlin-Bagdad Snake

Airmen In The Deserts Of Egypt

Europe: "Am I Not Yet Sufficiently Civilised?"

THE NEW ST. GEORGE

"Give us the means and we will slay this German dragon that threatens our towns, our women, and children."

Southend was bombed by about a dozen German aëroplanes this evening while the place was full of holiday-makers. The attack lasted a quarter of an hour and resulted in the death of twenty-three people, the majority of whom were women and children. About forty people were injured. One of the victims was a little girl, who was terribly mangled, and another was a woman, who was also badly mutilated.

Times, August 17, 1917.

From Raemaker’s Cartoons of the Great War Vol. III

ISBN: 9781909302815

Introductory

Thirty million soldiers, each living a great human story—this is the real drama of the Great War as it is being written into the hearts and memories of the men at the front. If these soldiers could be gathered around one camp-fire, and each soldier could relate the most thrilling moment of his experience—what stories we would hear! "Don Quixote," the "Arabian Nights," Dante's "Inferno," Milton's "Paradise Lost, and Regained"—all the legends and tales of the world's literature out-told by the soldiers themselves.

It is from the lips of these soldiers, and those who have passed through the tragedy of the war—the women and children whose eyes have beheld the inferno and whose souls have been uplifted by suffering and self-sacrifice—the generations will hear the epic of the days when millions of men gave their lives to "make the world safe for Democracy." The magnitude of this gigantic struggle against autocracy is such that human imagination cannot visualize it—it requires one to stand face to face with death itself.

A member of the British War Staff estimates that more than a million letters a day are passing from the trenches and bases of the various armies "to the folk back home." Another observer at the General Headquarters of one of the armies estimates that more than a million and a half diaries are being kept by the soldiers. It is in these words, inscribed by bleeding bodies and suffering hearts, that posterity is to hear True Stories of the Great War.

It is the purpose of these volumes, therefore, to begin the preservation of these soldiers' stories. This is the first collection that has been made; it is in itself an historic event. The manner in which this service has been performed may be of interest to the reader. It was my privilege to appoint a committee, or board of editors, to collect stories from soldiers in the various armies—personal letters, records of personal experiences, reminiscences, and all other available material. An exhaustive investigation has been made into the files of European and American periodicals to find the various narratives that have "crept into print."

More than eight thousand stories were considered. The vast amount of human material would require innumerable volumes to preserve it. It was the judgment of the committee that this documentary evidence could be brought into practical limitations by selecting a sufficient number of narratives to cover every human phase of the Great War and preserve them in six volumes.

This first collection of "True Stories" forms what might be termed a "story-history" of the Great War, although all chronological plan is purposely avoided in order to preserve the story-teller's "reality" rather than the historian's record.

These volumes are in the nature of a "Round Table" in which soldiers, refugees, nurses, eye-witnesses—all gather about the pages and relate the most thrilling episodes of their war experiences. We hear the tales of the soldiers who invaded Belgium, through the campaigns and battles on all the fronts, to the landing of the American troops in France. Diplomats tell of the scenes at the outbreak of the war; despatch bearers relate their missions of danger from Paris to Berlin, London, Vienna, Petrograd; refugees describe the flight of the Belgians, the exodus of the Serbians, the invasion of Poland. Emissaries at General Headquarters tell of their dinners with the Kaiser and the Crown Prince, with Hindenburg and Zimmerman, and describe the scenes inside the German empire. Soldiers from the Marne, the Aisne, Verdun—relate their experiences. We listen to passengers tossed into the sea from the Lusitania; revolutionists who overthrew the Czar in Russia; exiles returning from Siberia. We hear the tales of the fighters from South Africa, Egypt, Turkey; stories from the Far East along the seas of China. The lieutenant of the Emden relates his adventures. There are stories told by Kitchener's "mob"; the "fighting Irish," Scottish Highlanders, the Canadians, the Australians, the Hindus. The French hussars and poilus tell of their experiences; the Italians in the Alps, the Austrians in the Carpathians—the stories cover the whole world and every race and nation.

These personal narratives reveal the psychology of war in all its horrible reality—modern warfare on its gigantic scale—the genius of invention and organization applied to destruction. They reveal, moreover, the psychology of human nature and human emotions in all their moods and passions. The first impression is of the physical horror of the war, but this is soon overcome by the higher spirituality that impels men to sacrifice their lives for civilization and humanity. The stories sink at times into grossest brutality only to rise to the heights of nobility on the part of the sufferers. Officers tell of the charges of their battalions; the men in the trenches tell of the "nights of terror"; spies tell of their secret missions; nurses deliver the death-messages of the dying; priests tell how they carry the Cross of Christ to the bloody fields; the prisoners tell the "inside story of the prisons"; aviators relate their death-duels in the air; submarine officers tell how they torpedo and capture the enemies' ships. There is testimony from the lips of women who were ravaged; children who were brutally mutilated; witnesses who saw soldiers crucified; soldiers lashed to their guns; babies torn from their mothers' arms; homes in flames and ruins, cathedrals desecrated.

And yet there is an undercurrent of humanity in these human documents. In their physical aspect they are almost beyond human belief—but there is a certain spiritual force running through them. There is a nobility in them that rises above all the physical anguish.

These stories (and this war) reveal the souls of men as has nothing before in modern times. The war has taught men "how to die." These men have lost all fear of death. They have traveled the road of the crucifixion and stood before Calvary; they have caught a glimpse of something finer, nobler, truer than their own individual existence. Through suffering and self-sacrifice they have risen to the noblest heights. They have found something that we who have not faced death in the trenches may never find—they have felt an exaltation in mind and body that we may never know. There is the fire of the Old Crusaders about them; they have caught the realization of the glory of humanity as they march into the face of death. It is interesting to observe that wherever the story-teller is fighting for a principle, he sees no horror in war or death. It is only where he thinks of his individual suffering, where his thoughts are of his own physical self, that he complains.

And there is even humour in these stories; we see men laughing at death; we see the wounded smiling and telling humorous tales of their suffering; there is irony, cajolery, good-natured satire, and loud outbursts of laughter. And there is tenderness in them—kindness, gentleness, devotion, affection, and love. We find in them every human passion—and every divine emotion. They form a new insight into character and manhood—they inspire us with a new and deeper faith in humanity.

The committee in making these selections found that many of the human documents of the Great War are being preserved by the British, French, and German publishing houses, but it is the American publishers who are performing the greatest service in the preservation of war literature. We have given consideration wherever possible to the notable work that is being done by our American colleagues. While we have selected from all sources what we consider to be the best stories of the war, giving full recognition in every instance to the original sources, it is a pleasure to state that our American periodicals have been given the preference. They cordially co-operated with us in this undertaking and we trust the public will show their due appreciation. We would especially call attention to the list of books and publishers recorded in the contents pages of the several volumes; also to the periodicals which are preserving many of the human stories of the war. These will form the basis for much of the literature of the future.

As editor-in-chief of these volumes, I desire further to give full recognition to my associates: Mr. M. M. Lourens, of the University of Leyden; Mr. Egbert Gilliss Handy, founder of The Search-Light Library; Mr. Walter R. Bickford, former managing editor of The Journal of American History; and the staff of investigators at The Search-Light Library who made the extensive researches and comprehensive bibliographies—covering the whole range of literature on The Great War—required as a basis for the production of these books.

Francis Trevelyan Miller

DROPPING A BOMB FROM A DIRIGIBLE

It is Pleasanter to See This in a Volume Than Overhead!

A FEW MINUTES BEFORE THIS WAS A GERMAN BATTLE PLANE

But the Aircraft Guns Got His Range. The Insert Shows a Naval Plane

THE EYES OF THE ARMY

THE ROYAL FLYING CORPS

In this combination between infantry and artillery the Royal Flying Corps played a highly important part. The admirable work of this corps has been a very satisfactory feature of the battle. Under the conditions of modern war the duties of the Air Service are many and varied. They include the regulation and control of artillery fire by indicating targets and observing and reporting the results of rounds; the taking of photographs of enemy trenches, strong points, battery positions, and of the effect of bombardments; and the observation of the movements of the enemy behind his lines.

The greatest skill and daring has been shown in the performance of all these duties, as well as in bombing expeditions. Our Air Service has also coöoperated with our infantry in their assaults, signaling the position of our attacking troops and turning machine-guns upon the enemy infantry and even upon his batteries in action.

Sir Douglas Haig's Official Report onthe Somme Battle, December, 1916.

From Raemaker’s Cartoons of the Great War Vol. III

ISBN: 9781909302815

Turning Heavens Into Hell—Exploits of the

Canadian Flying Corps

Battle in Air With One Hundred AeroplanesTold by Officer of Royal Canadian Flying Corps

The heroism of the Canadians is one of the immortal epics of the War. The great dominion sent across the seas her strongest sons. Their valor in trench and field "saved the British army" on many critical moments. The feats of daring of these Canadians would fill many volumes, but here is one story typical of their sublime courage—a tale of the air.

I—WITH THE CANADIANS IN THE CLOUDS

There were one hundred of us—fifty on a side—but we turned the heavens into a hell, up in the air there, more terrible than ten thousand devils could have made running rampant in the pit.

The sky blazed and crackled with bursting time bombs, and the machine guns spitted out their steel venom, while underneath us hung what seemed like a net of fire, where shells from the Archies, vainly trying to reach us, were bursting.

We had gone out early in the morning, fifty of us, from the Royal Canadian Flying Corps barracks, back of the lines, when the sun was low and my courage lower, to bomb the Prussian trenches before the infantry should attack.

Our machines were stretched out across a flat tableland. Here and there in little groups the pilots were receiving instructions from their commander and consulting maps and photographs.

At last we all climbed into our machines. All along the line engines began to roar and sputter. Here was a 300 horsepower Rolls-Royce, with a mighty, throbbing voice; over there a $10,000 Larone rotary engine vieing with the others in making a noise. Then there were the little fellows humming and spitting the "vipers" or "maggots," as they are known in the service.

At last the squadron commander took his place in his machine and rose with a whirr. The rest of us rose and circled round, getting our formation.

Crack! At the signal from the commander's pistol we darted forward, going ever higher and higher, while the cheers of the mechanicians and riggers grew fainter.

Across our own trenches we sailed and out over No Man's Land, like a huge, eyeless, pock-scarred earth face staring up at us.

There was another signal from the commander. Down we swooped. The bomb racks rattled as hundreds of bombs were let loose, and a second later came the crackle of their explosions over the heads of the Boches in their trenches.

Lower and lower we flew. We skimmed the trenches and sprayed bullets from our machine guns. The crashing of the weapons drowned the roar of the engines.

I saw ahead of me a column of flame shoot up from one of our machines, and I caught a momentary glance at the pilot's face. It was greenish-ash color. His petrol tank had been hit. I hope the fall killed him and that he did not burn to death.

II—THE VULTURES OVER THE TRENCHES

Away in the distance a number of specks had risen, like vultures scenting the carrion that had already been made. It was a German squadron. The Archies had not bothered us much while we were spraying the Prussian trenches, but now we had that other squadron to take care of. Our orders were to bomb the trenches. We could not spare a bomb or a cartridge from the task of putting the fear of Britain into the hearts of the infantry below before our own "Tommies" should start over the top.

I don't know what it was, but suddenly, just after my partner had let go a rack of bombs, there was a terrific explosion just beneath us. My machine leaped upward, twisted, then dropped suddenly. Death himself was trying to wrench the control levers from my grip, but I clung to them madly and we righted. A few inches more and I couldn't have told you about this.

There was no longer any chance to worry about flying position. There were too many things occupying my attention—that line of gray down there that we were trying to erase and the Boche squadron thrumming down on us.

One drum of our ammunition was already used up. My partner whirled around on his stool—a sort of piano stool, which always made me think of the tuneless, tinpanny instrument back in quarters—grabbed another drum and slammed it into the machine gun. It was to be a parting message for the Prussians, for the commander was just signalling to retire.

My partner lurched forward. He was hit. A thin red stream trickled down his face.

I raced westward, the air whistling through the bullet holes in the wings of the machine and my partner leaning against the empty bomb rack, silent.

As we sailed over the foremost Prussian trench some Scotch were just leaping into it. The "ladies from hell" the Germans call them, because of their kilts.

Several machines had landed before I took the ground. Ambulances were dashing back and forth across the flying field.

They lifted my partner out of the aeroplane, but they did not put him into an ambulance. He had answered another recall. I walked to quarters ill—ill at heart, at stomach, at mind. I'll never know a better pal than was Tom.

On the way I managed to help with a machine that had just landed. A big Rolls-Royce it was, and the radiator had been hit by a bit of shrapnel. The pilot and observer were both terribly scalded.

Just by the aerodrome another biplane fluttered down. The observer was dead. The pilot was hit in a dozen places. Somehow he brought the machine in, switched off his engine and slopped forward in his seat, stone dead.

Ten minutes later I was sound asleep. The next day we were at it again.

In battles of this kind it is more or less a matter of good fortune if you escape with your life. Flying ability and trickiness can play but little part. It is in the lone adventure that stunt flying helps.

III—THE MYSTERIOUS MAJOR AND THE UHLANS

One of the most versatile flyers in the corps was the "Mysterious Major." Condon was his name, but to all the men, both sides of No Man's Land, he was the "Mysterious Major."

He was forced to glide to earth one day, back of the Prussian lines, with his big motor stalled. He leaped out hastily, adjusted a bit of machinery and spun the propellers. A gentle purr, then silence, was the response.

Once more he flashed the blades around, with no better result.

It wasn't a healthy neighborhood to be in. With a short, crisp oa [...]