Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Blix & Ramm

- Sprache: Englisch

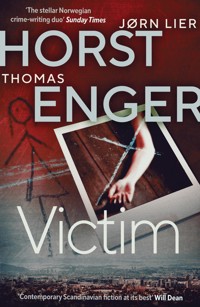

A cold case returns to haunt Blix, as a cold-blooded killer taunts him with evidence of further victims, while Ramm investigates a murder with no body… Blockbuster, explosive, No. 1 bestselling Nordic Noir. `Depressed cops are ten-a-penny in crime fiction but this is an exception, a sensitive portrait of a troubled man combined with a psychologically chilling plot´ Sunday Times `Contemporary Scandinavian fiction at its best´ Will Dean ______ Buried sins Brutal revenge… Two years ago, Alexander Blix was the lead investigator in a missing person's case where a young mother, Elisabeth Eie, was kidnapped. The case was never solved. Blix's career in law enforcement is now over, but her kidnapper is back, leaving evidence of Elisabeth's murder in Blix's mailbox, as well as hints that there are other victims. At the same time, Emma Ramm has been contacted by a teenage girl, whose stepfather has been arrested on suspicion of killing a childhood friend. But there is no body. Nor are there any other suspects… Blix and Ramm can rely only on each other, and when Blix's fingerprints are found on a child's drawing at a crime scene, the present comes uncomfortably close to the past. A past where a victim has found their own, shocking form of therapy. And someone is watching… Shocking, relentless and unbearably tense, Victim marks the return of the international bestselling, blockbuster Blix & Ramm series from two of Norway's finest crime writers. ______ Praise for the Blix & Ramm series… ***SHORTLISTED for the RIVERTON PRIZE*** ***SHORTLISTED for the PETRONA AWARD*** `Tense, brutal and fast-moving´ Sunday Times `Darkly twisty´ Crime Monthly `An international sensation´ Vogue `The most exciting yet´ The Times `If you're a fan of writers like Lars Kepler, Stefan Ahnhem or Søren Sveistrup, you won't want to miss this series´ Crime by the Book `Devilishly complex´ Publishers Weekly `Two of the most distinguished writers of Nordic Noir´ Financial Times `Full of twists!´ Sun `Completely nerve-wracking´ Tvedestrandsposten `Masterly´ NB Magazine

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 519

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

Two years ago, Alexander Blix was the lead investigator in a missing-person’s case where a young mother, Elisabeth Eie, had been kidnapped. The case came to a standstill when Blix’s own daughter was killed and he was arrested for avenging her. Now Blix is a free man once more, and Elisabeth’s murderer has found him, leaving evidence of her death in Blix’s mailbox.

The police are unwilling to accept Blix’s help: even if he was acquitted of his crime, his career in law enforcement is over. But Elisabeth’s murderer continues to pursue him, leading Blix to his new victims, while making it clear that he knows details from Blix’s private life that the former investigator has never shared with anyone…

Meanwhile, Emma Ramm has been contacted by a teenage girl, Carmen, whose stepfather has been arrested on suspicion of killing a childhood friend. But there is no body. Nor are there any other suspects…

Blix and Ramm can only rely on each other. And when Blix’s fingerprints are found on a child’s drawing at a crime scene, the present comes uncomfortably close to the past. A past where a victimhas found their very own form of therapy.

Shocking, relentless and unbearably tense, Victim marks the return of the international bestselling, blockbuster Blix & Ramm series from two of Norway’s finest crime writers.ii

iii

VICTIM

THOMAS ENGER & JØRN LIER HORST

TRANSLATED BY MEGAN TURNEY

iv

v

‘All that I am, or hope to be, I owe to my angel mother.’

—Abraham Lincolnvi

Contents

Prologue

The moon cast a dull light over the car park. A quick glance at the dashboard told him it was 1:34am.

He had returned to the area numerous times since burying her but had never ventured all the way to the exact spot. But despite the fact it was dark, he felt confident that he would find it. He knew the forest well.

It had rained the night before.

The grooves of his hiking boots would make deep, distinct impressions on the forest floor, which was why he had bought a pair he knew you would find in thousands of Norwegian homes. As for his clothes, he’d opted for a green waterproof coat, to blend in with his surroundings.

Planning, he thought.

Alpha and Omega.

He grabbed the bag from the boot. Locked the car and headed off down the trail. The air was cold, biting. Black clouds floated across the sky above him. A whiff of cool decay rose from the ground. His footsteps startled a couple of birds, who scattered violently into the air. After a few minutes, he could feel his scalp beneath his cap wet with sweat. The lenses of his glasses had fogged up.

It had not been without risk, carrying her into the forest as he had. Half of Norway was looking for her at the time. She was also much heavier than he’d expected. But it was night, like now. Besides, as always he had planned ahead.

Three nights beforehand, he had taken a collapsible metal shovel with him and tried to dig out a good spot. At the first potential burial plot, there had been far too many stones, the rock bed far too deep. As for the next, it had been impossible to dig deep enough – he didn’t want to risk some animal catching her scent and digging her up. Only on the third attempt had he succeeded in finding a suitable place, which was also hidden behind a clump of trees, bushes and ferns. Before going back, he had carved a symbol into the nearest tree. 2

The spruce had grown significantly since then. Its branches wider, maybe also a little thicker. He put down his bag and took out the shovel, glad to see the ground was not yet frozen.

The first plunges were the hardest. He had to penetrate a thick layer of heather and moss, roots that stretched out like a grid beneath the forest floor. It took him a while before he finally reached her.

He dropped the shovel and continued with his hands, to avoid tearing the plastic sheet he had wrapped her in. His gloves tunnelled into the damp ground. More and more of the plastic came into view.

He opened his jacket pocket and took out the piece of folded paper, carefully, not wanting to risk ruining it. Just as gently, he pulled back the plastic, layer by layer. And there she was: free and exposed.

There was a time for everything, he thought.

And now, the time was right for this.

During the day, the forest was a popular hiking area. People let their dogs roam off the lead, run freely among the trees. And if it did take too long for her to be found, he would just report the discovery himself.

The last thing he had planned to do took him less than a minute. Once completed, he stood up and looked around, satisfied. Above the treetops, a cloud drifted aside, and the moon peeked out, illuminating the burial site.

It was Tuesday morning. Now 4:15am.

He smiled.

It was going to be a good day.

1

The ground in front of him was a grey-brown, speckled with white spots here and there from the chewing gum that had been trampled into the pavement. Alexander Blix kept his eyes a metre ahead as he did his best to steer clear of the litter and old dog poo.

A sudden gust of wind made him pull his jacket collar tighter around his neck. Above, the clouds had started the gather. It would only be a matter of minutes before the first drops of rain would fall. It had been sunny when Blix left home just a short while ago.

Oslo, he thought.

Summer one second, autumn the next.

Only when the Grønlandsleiret 44 building, with its tall windows, appeared on the left did he lift his gaze and come to a stop. A woman stood smoking by the front door. A little further away, someone was shouting in a foreign language. Red and yellow leaves were strewn across the grass of the park next door. A stubby-legged dog darted back to its owner, holding a stick between its teeth.

They must have finished their morning meetings by now, Blix thought. Nicolai Wibe was probably propped up by the coffee machine, bragging about something he had accomplished in the gym that morning. Tine Abelvik likely snorted and rolled her eyes, while Gard Fosse, overbearing as he was, probably told them to get on with the day’s work.

Blix’s eyes were drawn to a car emerging from the building’s basement car park. As soon as it pulled out onto the road, its sirens blared. The car’s blue lights flashed over the façades of the buildings lining the road.

Other motorists pulled aside. The uniformed officer in the car’s passenger seat cast a long look at Blix as they passed. He couldn’t remember seeing her before.

He wondered what they were responding to – whether it was a burglary, an accident, a murder or something else. The car continued wailing towards the city centre, the sound gradually disappearing as it blended 4in with the sounds of the city, just another instrument adding to the cacophony of Oslo’s orchestra.

Blix turned back to the police station. A raindrop hit him on the cheekbone, and more quickly followed. He pulled back the sleeve of his jacket. A glance at his wristwatch made him realise he was late.

He turned around.

Noticed a person do the same – they immediately picked up speed and crossed the street at an angle without turning to check the traffic approaching. A motorist blared its horn at him. The man disappeared into the throng of people on the other side and continued with hasty steps.

The same guy, Blix thought.

The same dark-green waterproof, the same black backpack. Blix had seen him in the street outside his apartment, sometimes late at night, other times early in the morning. He had seen him at the shop too, and once – maybe but he wasn’t one-hundred-percent sure –in the courtyard of his apartment block.

Blix tried to speed up himself, but quickly realised he wouldn’t be able to catch up with him. The man disappeared down the steps into the subway station at Grønland Torg and vanished.

Blix continued towards the city centre, faster now, no longer concerned about where he put his feet. He turned often, each time with the feeling that everyone was staring at him. But the man in the green raincoat was not one of them.

2

Eleven minutes later, Blix arrived at the entrance to Leirfallsgata 11. An electric bike was propped up against the wall. It was raining lightly.

Hesitantly, Blix raised his index finger to the intercom beside the door, but paused and pulled it back.

You don’t have to, he told himself. You could just turn around and go home. Regardless, he found Krissander Dokken’s name on the wall panel and drilled his index finger into the light-green doorbell. A mere second later, the door’s locking mechanism clicked open.

Blix took the stairs up to the second floor, where a door stood ajar in the short corridor. He tentatively pushed it open. Inside, Krissander Dokken met him with an outstretched hand and a measured smile. In his other hand, he clutched the cane he was leaning on.

‘Please, come in.’

Blix took off his shoes and hung up his now-wet jacket. Without saying anything, Dokken showed him into a room where two chairs were placed at a good distance from each other with a small, round coffee table in between them. On the table was a water carafe filled to the brim, along with two glasses. A thin, white tissue poked out of a small, square box.

Blix sat down on the chair furthest from the door and crossed one leg over the other. A deep breath provoked a sharp pain in his chest. He tried to tell himself to relax, but it did nothing.

Krissander Dokken took a seat in his regular chair, placed his cane next to it and lay a notepad on his lap. On the wall behind him was a familiar print of a Vincent van Gogh painting. On the floor next to a white bookcase: a terracotta pot with a luscious green Guiana Chestnut plant.

‘So,’ Dokken began, adjusting the round glasses that barely covered his eyes. ‘How are you? How have you been since we last spoke?’

Dokken spoke slowly in a light, dry voice. Blix didn’t know how to answer. He could say that it still felt like an invisible force was pushing 6him down into his bed when he woke up in the morning, keeping him there. That there wasn’t a minute of the day when he didn’t think about Iselin and the man who had killed her. When he didn’t think about all that he, himself, had done afterwards. His time in prison. The time since he had been released.

Instead he said: ‘Good.’ And swallowed. ‘I guess I’ve been … pretty good.’

‘What does that mean?’ Dokken looked at him intently.

‘Uh,’ Blix said, shrugging it off. ‘I don’t know really.’

‘What does it mean to you to be pretty good?’

It took a few moments for Blix to answer.

‘That’s a good question,’ he said. ‘Maybe I don’t really know what that means or includes anymore.’

Dokken nodded slowly. ‘What do you think you have to do for things to be or feel better?’

Blix thought about it. Thought for a long time.

‘I don’t know,’ he said. ‘I’ve no idea.’

‘Have you tried meditating yet?’

Blix shook his head. ‘I’ve … not quite got round to it.’

A long silence stretched across the table between them.

‘What have you been up to for the last few weeks, then?’

‘Not much, really. I … read a lot. Newspapers, books. And then I tie … flies.’

‘As in … flies for fly fishing?’

‘Yes, it’s an old hobby I’ve taken up again.’

‘That’s good. I’m glad to hear it. Do you fish a lot?’

‘Not anymore. Before, I did. In the old days.’

‘Maybe you should test out your new flies sometime soon?’

Blix shrugged. ‘Maybe.’

Dokken waited a moment, then asked his next question.

‘Are you eating?’

‘Yes, I’d say so.’

‘Are you eating healthy food?’

Blix thought about it. 7

‘Not as often as I should do, no.’

‘We are what we eat, you know.’

Dokken tried sending him a small smile. Blix didn’t return it.

‘What’s your sleep pattern like?’

‘A little disturbed. As it’s almost always been though, even back when I was working.’

Dokken moistened his lips. ‘Do you still do your usual morning walk?’

‘Mostly.’

‘The same route?’

‘Yes, I’ve not really made many changes. I guess I’m a creature of habit, like almost everyone else.’

Dokken brought his hands together and steepled his fingers. ‘Do you still feel like you’re being watched, or like someone’s following you?’

Blix had forgotten that he’d told Dokken that.

‘No,’ he answered, a wave of heat rising to his face. ‘But a lot of people know about me, now,’ he added. ‘After … everything that happened. Someone always seems to recognise me when I’m out on the street or shopping or whatever.’

‘Ah, the price of fame,’ Dokken said with a faint smile. ‘I’m glad I’m not famous.’

Blix said nothing.

‘Are you still receiving the same amount of letters?’

Blix thought about it.

‘Maybe a little less now.’

‘What kind of letters are you receiving then?’

‘I don’t know, I don’t really look at them.’

‘Why not?’

Blix considered the question. He didn’t really have a solid answer.

‘Do you keep in touch with anyone?’ Dokken asked.

‘Emma,’ Blix replied. ‘Emma Ramm. Occasionally.’

‘No former colleagues? None of them message, invite you out for a beer or anything?’

Blix shook his head. 8

‘So there’s no one you reach out to either?’

‘No. Unless we’re counting Merete. My ex-wife. But even that’s only every so often.’

Dokken stared ahead for a few moments, as if he were deep in thought.

‘What about your parents?’

Blix looked up at him abruptly. ‘What about them?’

‘Are they still around?’

‘Do you mean, are they still alive?’

‘M-hm?’

‘My father is … ’ Blix said with a heavy sigh. ‘My mother died a long time ago.’

‘How old were you then?’

Blix pushed himself up a little in his chair. Quickly scratched his cheek with an unexpectedly sharp fingernail.

‘Sixteen.’

‘Do you have any contact with your father?’

Blix put a hand on his thigh and squeezed a little on the muscles under the fabric.

‘Not so much.’

‘Why not?’

‘He’s … in a nursing home.’

‘Does that prevent you from having contact with him?’

Blix looked down and interlaced his fingers. Didn’t answer.

‘Why is he in a nursing home?’ Dokken continued. ‘If you don’t mind me asking?’

‘He … can’t take care of himself anymore.’

Dokken nodded slowly. ‘Where is this home?’

‘Just outside Gjøvik.’

‘Is that where you’re from?’

‘Close. I’m from Skreia.’

‘Skreia,’ Dokken repeated, as if the place itself were important. ‘When was the last time you visited him?’

‘I don’t remember.’ 9

‘Was it before or after you were in prison?’

‘Before,’ Blix answered quickly.

‘When was the last time you spoke to him?’

‘I don’t re — ’ Blix stopped himself. ‘It’s been a while.’

Blix noticed that the psychologist now had deep frown lines between his eyebrows.

‘Perhaps you should take another trip,’ he said. ‘If for nothing else, then to — ’

‘No,’ Blix interjected.

Dokken gazed at him for a while.

‘Why not?’

‘I don’t want to.’

Silence descended again.

‘What was your relationship like with your mother?’

Blix sighed. ‘Good,’ he said. ‘Let’s talk about something else.’

Dokken scrutinised him a while longer. Sat back in the chair and crossed one leg over the other.

‘Let’s get back to what we started this session with,’ he said. ‘What it means to you to feel pretty good. After all, that’s what we’re all aiming for, mostly. Each day, and throughout our lives.’

He drummed his fingers on the notepad, seeming to weigh his next words.

‘You were in prison, Alexander, for almost eight months. But you were acquitted in the Court of Appeal. And you’ve now been a free man for a little over two months.’

‘It depends on what you mean by “free”,’ Blix objected. ‘I’ll never be completely free from what happened, or from what I’ve done. None of that ever goes away.’

‘No, but that’s the same for everyone,’ Dokken said. ‘We carry everything we’ve ever done and experienced throughout our lives with us, whether they be short or long. That’s just a part of us. We can’t go back and change any of it. It is only you, me – we – who can do anything about our own future.’

‘So I just have to get over it? Is that what you’re saying?’ 10

‘Not at all,’ Dokken replied, unfazed by Blix’s raised voice. ‘What you have experienced will always affect you. But what we’re doing here isn’t trying to patch up your wounds so they stop bleeding. Rather, we want to do the opposite: we want to open them up and let the blood run as long as is necessary. In the long run, we want to try to train your body and brain to just let it bleed without you thinking too much about it, or feeling the pain to the same extent.’

‘That doesn’t sound abstract at all,’ Blix said sardonically.

‘But it’s actually not abstract,’ Dokken replied. ‘There are a number of specific techniques that have proven to be very effective for people struggling with major trauma or deep grief.’

He waited until Blix looked at him then said: ‘Have you heard of EMDR?’

Blix shook his head.

‘EMDR stands for Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing. It’s a way to stimulate the brain in order to make it easier to live with negative experiences.’

Blix raised an eyebrow.

‘When we experience something traumatic,’ Dokken continued, smoothing out a crease in his sky-blue shirt, ‘our ability to process emotions and memories can be completely thrown out of whack. It’s all simply too overwhelming. The pain is too great. What we do with EMDR is reprogramme the brain to process stress and trauma without activating the same strong emotional reactions.’

Blix could hear Dokken go into more detail about exactly how this worked, but his mind drifted back to the man in the green raincoat.

‘We can try something called EFT too,’ Dokken said after a while. ‘Or tapping. Which is another technique. That’s something you can do at home too, on your own.’

Blix stroked his chin but said nothing.

‘You have said before … ’ Dokken cleared his throat ‘…that it goes against your own sense of justice that you are no longer in prison. Because you shot and killed a man.’

‘It was an act of revenge,’ he said quietly. 11

‘You prevented him from harming, or even killing, Emma Ramm.’

‘True, but I was primarily thinking about punishing him, not saving Emma. And that’s the honest answer.’

Dokken watched him.

‘I shouldn’t be here,’ Blix said. ‘I don’t mean here, specifically, in your office. I mean … out. I should have plead guilty and taken my sentence like any other offender.’

‘And you feel guilty about that.’

Blix looked up at him. ‘Yes.’

Dokken drummed the pen against the notepad.

‘But so what if there was an element of hatred, revenge or punishment involved?’ he said. ‘Who wouldn’t react the same way to a man who took the life of one’s own child?’

Blix looked down. Said nothing.

‘That doesn’t make you a bad person.’

‘Perhaps not,’ Blix said. ‘But it does make me a bad policeman.’

‘Is that what defines you as a person?’ Dokken asked. ‘The kind of policeman you once were?’

Blix had no answer.

‘And another thing – would it make your life better if you hadn’t stopped him? If he had gone ahead and killed Emma Ramm too?’

Blix continued staring at the floor.

‘In a way, you’ve actually been given a second chance.’

‘Not really,’ Blix responded. ‘I can never work as a policeman again.’

‘No, but it’s not beyond the realms of possibility to think of this freedom as a gift. It’s happened before, and with people who have done worse than you. It is possible to do something with that freedom. That gift.’

Blix stared at him. ‘Like what?’

‘I can’t give you the answer to that. That is something you have to find out for yourself.’

Again, silence.

‘May I make an observation?’ Dokken asked after a while.

Blix looked up at him. Waited. 12

‘It seems like you’re flogging yourself,’ Dokken began. ‘First and foremost because you failed to save your daughter, but also because you killed a man and are now free. You even visit your old workplace every day. So you can remind yourself of what you did and what you’ve lost. That is a brutal thing to do to yourself.’

Blix didn’t answer.

‘Right now,’ Dokken continued, clearing his voice, ‘your own head is your worst enemy, because your mind is going in circles. You won’t get anywhere like that. You’re like a dog trying to bite its own tail.’

Blix listened but had nothing to say.

‘But,’ Dokken said, ‘you keep coming here, even after your previous experiences with people in my profession, and you do so voluntarily. That tells me that deep down you want to get help. That you do want to feel better. It shows a strength of character. And I would like to help you, Alexander. But you have to let me.’

Blix glanced up at the clock on the wall. Dokken followed his gaze.

It was quiet again.

‘In psychology, we have a concept we call self-compassion,’ Dokken began. ‘It’s about being kind to yourself. About acknowledging that yes, I am in pain right now. And at the same time saying that yes, it’s perfectly okay to feel that pain. It’s important to take care of yourself. And it’s important not to make things worse than they need to be.’

‘So I should walk somewhere else?’

‘That might be a good place to start,’ Dokken said. ‘And, as I’ve said before: get a dog, if you’re not allergic. Dogs are wonderful companions.’

Dokken spent the next few minutes sharing some anecdotes from his own life with his own four-legged friends, and what enrichment they had brought in difficult times. As the clock approached 11:45, he signalled for them to wrap up the appointment.

Blix stood up, sweat between his shoulder blades, glad the session was over. Dokken accompanied him out into the hall. After Blix had pulled on his still-wet jacket, Dokken said:

‘You should see your father. Even if you don’t feel like it. He might need it. And who knows,’ he said. ‘Maybe you need to see him too.’ 13

Blix bent down to tighten his shoelaces, even though he had just finished tying them. When he stood up again, he said nothing.

‘Do it,’ Dokken repeated. ‘Because one day, maybe soon, it may be too late.’

Blix buttoned up his jacket and reached for the doorknob.

‘Thanks,’ Blix said, without looking at him. ‘Enjoy the rest of your day.’

3

It didn’t take more than a couple of minutes before Emma Ramm realised what a mistake she had made. It was by no means a disaster though, to enter the Botanical Garden without the slightest knowledge or interest in shrubs and plants. She had always appreciated the aesthetic things in life, but when her walking partner had four legs and a level of curiosity about every single thing happening around them that was a little more than the average, then the experience suddenly became a lot more frantic.

Terry was a Tibetan terrier who she had been told was a ‘laid-back’ dog, but could also be a lively, friendly little guy with ‘many charming traits’. He was supposed to be both outgoing and smart, and not particularly aggressive or difficult to deal with. But – and this was the big but – he could also be ‘not quite as loyal to strangers’. Which, really, was what Emma was to him.

Be firm, she told herself, almost like repeating a mantra. Regardless, it was Terry who pulled her to the right, yanked her to the left – desperate to experience all the exciting smells and traces of something or other across every nook and cranny of the Botanical Garden – which probably had more nooks and crannies than anywhere else in Oslo.

When she eventually managed to get Terry to take a breather at the top of the hill, or rather on a bench where she could look out over the upper Grønland district, she wondered what the previous owners had done with him. The only thing she knew about him was that he had been adopted from a shelter.

Emma checked her watch.

Blix was late.

She passed the time by scrolling through the news sites on her phone. It was a wonderful feeling to be able to do so without the fear that her competitors had discovered a case she should have covered herself, without having to think of all the angles she should tackle a story from as soon as she read an item she knew would dominate the news for the next few days. 15

It had taken time to shake off those old habits, those old ways of thinking. It had taken time to get used to detaching herself from her old routines too, such as getting up early in the morning to exercise before the work day began. Now she could sleep in until half-seven before hopping on her bike or sliding into her running trainers and taking to the streets to try to keep up with the city’s light-blue trams.

Emma’s phone vibrated in her hand.

It was a number she didn’t recognise. She usually let unknown callers ring through to voicemail – she hated talking to telemarketers or people wanting her to take part in some dull market research. This time though, she answered, seeing as she still couldn’t see any sign of Blix.

‘Is that… Emma Ramm?’ The voice on the other end sounded like it belonged to a young girl.

‘It is?’

‘Hello. I … ’

A prolonged silence. ‘My name is Carmen,’ the girl eventually said. ‘I’m sorry that I … ’

She stopped again. Emma straightened up and planted both feet on the ground.

‘I was wondering if I could have a chat with you?’

Emma frowned. For a school assignment, perhaps, she thought. A student who had found her name in an article about the topic of whatever project they were doing. It had happened before.

‘Sure you can,’ Emma replied. ‘What about?’

‘I’d rather not say over the phone. I … ’

Again, silence on the other end.

‘Sorry,’ she said. ‘I’m not very good at talking over the phone.’

Emma felt a wave of sympathy for the young girl. ‘Do you want to talk in person?’

‘Yes. Or, no. Um, yes. If that’s okay. If you have time?’

Emma glanced at her wristwatch, even though she knew that time itself wasn’t a problem.

‘Can I ask why you want to talk to me in particular, Carmen?’

‘Because … ’ 16

The seconds ticked by. Emma heard a sniffle on the other end. Then another.

‘Forget it,’ she said abruptly. ‘Sorry for bothering you.’

And the next moment, the line went dead.

Emma looked at her phone. A quick online search revealed that the number of the girl who had called her was registered to a Victoria Prytz.

‘Whoa,’ Emma said out loud.

The next moment, Terry sprang to life. Emma immediately understood why – Blix was walking up the hill towards them. Terry charged at him, hauling Emma up from the bench. She had to hold on tightly to the lead in order not to be dragged along the tarmac after him.

Blix bent down as Terry jumped up at him, tail wagging back and forth. Leaping at his face, then back to the ground, doing a spin, before leaping up at Blix’s face again with an eager, soaking-wet tongue. Blix received the love, joy and the biggest welcome in the world with a gentle smile.

‘Hi,’ he said to Emma when Terry finally finished the welcoming ritual.

‘Hello.’

Emma released a heavy sigh. Blix, she saw, had even darker bags under his eyes than when she had seen him earlier that day. The skin beneath his chin looked flushed.

‘How did it go?’ she asked.

Blix looked around quickly. ‘You know that those sessions are confidential?’

‘Um,’ Emma said. ‘It’s only the psychologists who have to keep their traps shut. You, on the other hand, can run your mouth all you want. Especially to someone who’s looking after your dog.’

She winked, sent him a smile. Blix took the dog lead from her. Terry had calmed down a bit, was now preoccupied with an invisible trace of something along the edge of the tarmac.

‘Everything go okay?’ he asked, nodding towards the dog.

‘Yeah, all fine,’ Emma lied. ‘We’ve had a great time together.’ She tried not to roll her eyes.

They walked down the hill, towards Jens Bjelkes gate. 17

‘What’re you up to for the rest of the day?’ she asked.

He glanced up at the clouds. It wasn’t long before it would start raining again. ‘I’m … heading home, I think.’ He studied his surroundings. Followed a car with his eyes as it drove towards Sofienberg.

‘I’ll walk with you.’

They continued towards Tøyengata.

Emma thought of the young girl who had called her. Carmen, who by all accounts seemed to be the daughter of Victoria Prytz and therefore the stepdaughter of Oliver Krogh. Emma was about to tell Blix about the phone call, but could see that he was lost in his own thoughts.

‘You’re not going to tell me then?’ she asked.

‘About what?’

‘Um, hello?’ Emma said dejectedly. ‘You were there for three quarters of an hour.’

‘Yes, but … ’

He looked away.

‘Have you heard of EMDR?’ he finally asked.

‘What’s that, a new country in Eastern Europe?’

There, a slight movement in his smile lines. Emma almost felt like patting herself on the back.

‘No, never heard of it,’ she said. ‘What is it?’

‘Just something,’ Blix said, shaking his head.

‘Just something?’

‘Yeah, some … psychobabble nonsense. Nothing I’m going to try.’

But you still mentioned it, Emma thought.

They made their way down Tøyengata. A red bus drove by in the opposite direction. And a few minutes later they arrived outside number nineteen, where Blix lived.

‘Thanks for looking after Terry,’ he said with a long sigh, glancing down the road. ‘He … doesn’t do well, being home alone.’

‘You’re welcome.’ She looked at him. Suddenly burst into laughter.

‘What is it?’

‘No, it’s just funny, that’s all,’ she said. ‘You’re probably the last person in the world I would have thought would get a dog.’ 18

‘What makes you say that?’

She looked down at Terry, who had plonked himself down on the ground beside Blix. His tongue lolled out of the side of his mouth. It looked like he had a heart rate of 350.

‘I didn’t think you even liked dogs.’

Blix glanced quickly over Emma’s shoulder, as if scanning the area for something. She turned to look in the same direction, but saw nothing of note.

‘And then all of a sudden this guy moves in with you. Something completely dependent on you to survive.’

Blix said nothing.

It hit her then, that perhaps it was just as much the other way round.

‘You’re a stimulating conversation partner, Blix. Informative and inclusive.’

‘Sorry,’ he said with a faint smile. ‘I’m just a little tired.’ Again he glanced over her shoulder.

‘Are you expecting a visitor or something?’

‘No, no,’ he said. ‘I just … ’ He looked down.

Emma scrutinised him. ‘You do know I can read you pretty well at this point, right?’

Blix sighed but didn’t answer.

‘Is something going on?’ she asked.

‘No, no. It’s nothing,’ he said.

‘Are you sure?’

‘Yes.’

He looked at her and shook his head. Emma didn’t believe him for a second.

‘Okay,’ she said anyway. ‘I’ll leave you be. You’ll tell me one day.’

Blix seemed disconcerted as she bent down.

‘Thanks for today, Terry,’ she said, patting the dog on the head. ‘It’s been a pleasure.’

Terry tried to nip her hand in return.

4

Standing at the post boxes in the hallway was Holger Evensen, a man a few years younger than Blix, who had moved into an apartment at the back of the building in the spring. Despite the fact that it was now cold out, Evensen was only wearing a white T-shirt and a pair of well-worn joggers. He gave Blix an exasperated look when Terry lunged over to say hello.

‘You know you have to apply to the condominium for permission to have a dog here, right?’ There was a hint of disdain in his voice. With irritated movements, he took out his mail.

‘He’s a rescue dog,’ Blix tried to argue.

Holger Evensen snorted and started up the stairs as he leafed through his letters, his slippers slapping on the dirty steps.

Blix’s post box was half full of junk mail and bills. A couple of envelopes of a more personal nature had also found their way in. There was sender information on the back of two of them – R. Nakstad from Honningsvåg and Alma Söderqvist from Uddevalla.

Sweden now too, Blix thought. That’s a first.

He walked back out into the courtyard, kept two bills and threw the rest into the paper recycling bin.

He heard the sound of a door opening and slamming shut on the floor above. Blix hurried back to the front door, unlocked it and made for the stairs. Once on their floor, Terry abruptly planted himself on the carpet in the hallway. His ears were pushed back and his snout twitched, as if he could smell something new, foreign. Blix had to prod him forward with his foot until they were finally inside the flat and he could close the door behind him.

‘What is it?’ he asked, unclipping his lead.

Terry strolled off, unconcerned. Claws click-clacking against the wooden floor.

Blix hung up his jacket and followed him into the kitchen.

He put down the post and filled Terry’s water bowl. Warmed up the 20leftovers from yesterday’s stew and tucked in with two dry slices of bread. The clock on the wall steadily ticked away, like an eternal reminder that life goes on.

Terry settled down at his feet. Blix considered whether he should get some sleep himself, but could feel in his body that he wouldn’t be able to. Instead he went into the small study and sat down to work on one of his flies. The Antron yarn which, with some difficulty, would become the fly’s tail, had twisted itself around the hook shaft.

He took a deep breath, untangled it, and began again, until he was satisfied. It looked better this time.

He had just finished weaving two peacock feathers into the attachment point above the barb when his phone rang in the kitchen. Blix remained seated, concentrating on his work. With each ring, he became more and more irritated. Whoever was calling finally gave up.

He finally managed to attach the feathers to the hook eye when the ringing started anew.

‘Goddamn it,’ he muttered, and stood up.

The movement was a little too sudden. His lower back throbbed. He limped into the kitchen. The display showed no number, just the word ‘unknown’. He answered with a grumpy hello.

‘Took your time,’ a distorted voice answered on the other end. It sounded muffled, as if a piece of cloth had been placed over the receiver.

‘Who is this?’ Blix asked. ‘Who am I talking to?’

No answer. Instead, the voice said: ‘I would like to make a confession.’

Blix moved the phone to his other ear. It sounded like the caller was purposely lowering his voice by a couple of octaves.

‘What do you mean?’ Blix asked.

‘I would like to make a confession,’ the man repeated.

Terry had woken up. He got up from his blanket and lay down under the table.

Blix wasn’t sure if the person on the other end meant he simply wanted to admit to some error, or he was talking about confessing to something more serious.

‘If you really mean it,’ Blix began, sitting down. ‘If you want to confess 21to a crime, then you’ve got the wrong person. I no longer work for the police.’

‘I put it in your post box.’

‘Huh?’

‘My confession. I put it in your post box. But … ’ He paused. ‘…It’s no longer there.’

Blix glanced over at the bills he had brought in. Felt his heart pounding.

‘You shouldn’t just throw away what people send you, Blix,’ the man continued. ‘It’s rude.’

The motor in the fridge kicked in and made a steady hum. Blix swallowed, unsure whether, or how, he should continue the conversation. It didn’t matter – in the next moment, the connection was cut.

Blix sat with the phone in his hand for a few moments. Then pushed himself up and walked towards the door. Terry followed, but Blix shot him a stern look and held up a flat hand: ‘Stay!’

Terry obediently laid back down. Blix hurried out of the door and down the stairs. In his haste he forgot both his phone and keys, but there was always a door wedge downstairs he could use to prop the front door open.

There were lights on in several of the windows around him. A brief movement behind the curtain of a window on the first floor, but otherwise, he didn’t see anyone.

He opened the recycling bin, glad that the bin lorry wasn’t due today. It only took a moment before he found the stack of letters he had thrown in there. He filtered through the junk mail and found the envelopes. Opened the letter from R. Nakstad first.

There was a picture and a handwritten letter inside. The R stood for Regine. Blix quickly realised that she was just a lonely woman. He crumpled the paper up and looked around again. Two boys walked by on the street, each with a gym bag slung over their shoulders, but neither of them paid him any attention.

He tore open the next envelope. Alma Söderqvist would like to invite him to Uddevalla. That letter was also thrown back into the bin as soon as it was opened. 22

The last envelope had no name on it, neither for the recipient nor the sender. It really just looked like generic, unaddressed advertising.

He squeezed it to check its contents. A photograph, it felt like.

Tentatively, he slid his index finger under the edge of the glue and popped open the envelope.

‘Jesus,’ he muttered to himself.

It was a Polaroid picture of a woman.

Elisabeth Eie.

The mother who had been missing and presumed dead for almost two and a half years.

5

Emma was sitting on a bench dappled with damp spots. From the top of St. Hanshaugen park, eighty-three metres above sea level, she could see well into the Oslo Fjord. A cruise ship curved its way through the narrow inlets, heading for Skagerrak’s open waters. The cloud cover was dense. There was a chill in the air.

It was 5:30pm.

Carmen Prytz was still nowhere to be seen. Emma opened her phone messages and quickly scrolled through the brief communication they had had earlier that day. Curiosity had prompted her to get in touch and say that of course they could meet – just choose a time and place and I’ll meet you there. She hadn’t expected to hear back, but a response came anyway, a good hour later. Just a time – 5:30 – and a meeting place. Nothing else. It was now approaching 5:40. Still no sign of Carmen. Emma texted her to say she was there, adding a smiley face. No response.

It had been just over two months since Emma had quit her job as a journalist. She had been sure that she would use all this free time to figure things out and make a start on something new, but she still had no idea what to do next. It had been a great feeling at first, having no responsibilities. Everything was possible, open. She had even considered going back to university, but for what? What would she do?

Emma had thought that the right career path would materialise for her one day, as if there was a place in the universe meant just for her. Perhaps it was an overly romantic and childish idea. In the meantime she took each day as it came, making the effort not to worry too much. This did make her everyday life easier, in a way, but it also made it more difficult. More boring. Emptier. Work out, eat, sleep, read a bit, fix a few things in the apartment, take a trip to IKEA. Spend time with Irene and Martine – her sister and niece – go out with a couple of friends. Go back home with a stranger, but never spend the night.

Not exactly sustainable in the long term. 24

She had to make money, too. The book she had written had been well received, but had been nowhere near a bestseller.

It was now 5:45.

Carmen had obviously got cold feet.

Emma stood up with a sigh and straightened her trousers a little. And was about to head off when she caught sight of a girl approaching with tentative steps. She was wearing an oversized black hoodie and was looking nervously in Emma’s direction.

Emma recognised Carmen from her Instagram thumbnail. Her account was private, so that was all she’d been able to see – and basically all the public information Emma had been able to find about the girl she was going to meet.

Emma waved.

Carmen slowly came closer. Emma met her with a smile and an outstretched hand. Carmen reciprocated nervously. Her thin fingers were warm.

‘Sorry I’m late,’ she said. ‘My mum, she … ’ Carmen stopped herself.

The girl in front of Emma had long, light-blonde hair and a round, full face, badly afflicted by skin problems. It looked like she had a rash around her mouth. On other parts of her face, slightly larger spots had dried up and left angry, dark-red crusts. The teenage years, Emma thought. A terrible, merciless time, in so many ways.

‘That’s okay,’ she said gently. ‘Shall we sit?’

Emma gestured towards the bench she had just got up from. Carmen sat down and put her hands in her lap. Squeezed her fingers a little, brought one of them up to her mouth. Started biting her nail. Took it out, examined it.

‘Thank you for agreeing to meet me,’ she said without looking at Emma. ‘I … wasn’t sure if I should come.’

Carmen seemed shy and unsure of herself. Emma had met many girls just like her back when she was a young girl herself – not least when she had looked in the mirror.

‘What can I do for you?’ she asked.

The teenager waited a few moments. 25

‘Do you know who I am?’ she asked, shoving her hands deep inside the pockets of her hoodie.

Emma nodded. ‘Kind of.’

‘Then you’ve also seen what’s going on with my stepfather, Oliver Krogh?’

‘It’s been hard to miss,’ Emma said.

Oliver Krogh was in custody, suspected of having killed a childhood friend. At the end of July, Bull’s Eye – Krogh’s hunting and fishing store – had burned to the ground. It was first assumed that Maria Normann, who worked for him, was inside, and that Krogh had set fire to his own shop.

Maria Normann had still not been found, yet a few days after the fire, Krogh was arrested.

Whatever his motive was, the media hadn’t yet been able to find it. So far no charges had been brought against him, but everything seemed to indicate that they were imminent.

‘He’s innocent.’ Carmen took out a round, dark-blue tub from one pocket and unscrewed the lid. Dipped her little finger into it and rubbed the moisturising balm over her lips. ‘My stepfather couldn’t have killed anyone,’ she said, putting the tub back.

‘What makes you say that?’

‘He’s just not like that.’ Carmen shook her head.

Emma could see that the girl was on the verge of tears.

‘What does he have to say about what happened that day?’ Emma asked.

‘He denies it, of course.’

‘Does he have any idea who might have done it, then?’

She hesitated a little, then shook her head. ‘We … talked to the lawyer about hiring a private investigator, but Mum … didn’t want to.’

‘Why not?’

‘She … said it would be too expensive. But the most important reason was probably that … ’ Carmen lowered her head. Started to cry quietly. She sniffed and apologised.

‘Oh, hun,’ Emma said, placing a hand on her arm. ‘There is nothing to apologise for.’ 26

Carmen wiped her cheeks. ‘They were drifting apart, I think, even before all this happened. And afterwards, after he was arrested … ’ She shook her head. ‘It didn’t take long before she said that she wanted a divorce. I think she was glad to have someone to blame. It made it easier, or something.’

‘Easier to leave him, you mean?’

‘Yes.’

‘So she doesn’t believe him either?’

Carmen sighed. ‘I don’t think so.’

They both fell silent for a while.

‘So … your mother doesn’t know you’re here?’ Emma asked. ‘She doesn’t know you’ve contacted me?’

Carmen looked up at her. Shook her head.

‘Are your parents still together?’ Carmen asked after another minute’s silence.

Emma pondered how best to answer her. The fact that her mother was shot and killed by Emma’s father was not something she usually spoke freely about to just anyone. She merely shook her head.

‘Carmen, before we go any further: You know I’m not a journalist anymore, right?’

‘Yeah, I … read that.’

‘But still you wanted to talk to me about this?’

A couple of seagulls were squabbling over a meal on a patch of grass a small distance away. It was difficult to say who was winning.

‘No one will help him,’ Carmen said. ‘The police seem convinced he did it. He’s all alone.’

Emma suspected that the young girl had been in contact with other, more high-profile journalists before her.

‘I read about you online,’ Carmen continued. ‘It said that you’d received an award for your work. That you weren’t afraid to work on difficult, unpopular cases.’

Emma felt a little uneasy, but had to admit that Carmen’s call and Oliver Krogh’s case had piqued her curiosity. As a journalist, she had always been sceptical of overwhelmingly one-sided media coverage. But 27that didn’t mean it was wrong, or that she could do anything to balance the voices proclaiming the man’s guilt.

‘I know I’m asking way too much,’ Carmen said. ‘And I have nothing to pay you with either. I just don’t know who else to ask.’

Emma didn’t know what to say. Now having agreed to meet the girl, it felt wrong to turn her request down.

‘The police have been searching for Maria Normann, but haven’t found her,’ Emma said. ‘However, your stepfather is still in custody. Do you think the police might have some sort of evidence or indication that is telling them he’s guilty?’ Emma hadn’t found any suggestion of this in the media. ‘Have you, his family, heard anything like that?’

Carmen stared straight ahead. ‘We’ve only been told a little,’ she said.

Emma waited for the girl to continue.

‘They … found some blood,’ Carmen went on. Her voice was weak.

‘Blood?’ Emma asked.

‘Maria’s blood,’ Carmen explained. ‘They found traces of her blood in the ruins of Oliver’s shop.’

6

One of his neighbours met him at the door and tried to say hello, but Blix walked straight past her, up to the second floor. Terry was waiting for him back in the apartment. Blix ignored him, just continued into the kitchen and grabbed his phone.

Another missed call from an unknown number he couldn’t call back. He cursed, slumped into a kitchen chair and dropped the picture and envelope on the table. In the middle of the picture there was a small hole, as if it had been attached to a board with a pin or thumbtack. The point had been slotted through Elisabeth Eie’s head.

He stood up again, went to the cupboard under the sink and looked for a pair of rubber gloves. Found none, so took two plastic food bags with him and slipped the envelope into one and the picture into the other, without contaminating them further.

The Eie investigation had been his.

It had been a special case from the start. Two officers had come out of the Oslo Courthouse building one day and found a large envelope underneath the windscreen wipers of their patrol car. Blix’s name and job title had been written on the outside, along with a note stating that the contents were private and that delivery was urgent.

Blix had received it an hour later. The simple message had been written on a large, white piece of paper: Something is wrong with Elisabeth Eie. Her address and date of birth were also provided, so there would be no doubt as to whom the note was referring.

Blix had sent a patrol car to check her address. The apartment had been empty. Seven hours earlier, she had dropped her daughter off at the nursery and had then met with a case manager from child-welfare services. And that was the last time Elisabeth Eie was seen alive.

Blix found himself standing again, leaning on the table, palms down, staring at the photo of her. Her hair looked as if it were flowing around her. Her eyes were wide open. The skin on her face had a blue tinge. 29Everything indicated that she was dead, but he couldn’t tell from the photo exactly how she had been killed.

Whatever surface she was lying on was dark. Maybe brown. It could be a basement floor, Blix thought, or a carpet. There were no other details in the photograph that could help him determine where she was when it had been taken.

He straightened up, flipped the picture over and looked at the back. In the middle of the smooth surface, a black marker had been used to draw a cross where the pin had punctured the Polaroid. Surrounding that cross were three smaller crosses. This meant nothing to him.

Elisabeth Eie had been from Lillestrøm, but had moved about a bit. She had worked as a substitute teacher in a primary school. Her daughter was called Julie and after Elisabeth’s disappearance she had been taken into care by child welfare. The child’s father was a man in his forties who received disability benefits and was not considered fit to care for her.

He had a strange first name. Skage. Skage Kleiven.

Initially, much of the routine investigation had been focused on him, but Kleiven’s sick father had passed away two days before Elisabeth Eie disappeared. In the following days, Kleiven had been busy organising his father’s affairs and funeral. Among the places he had been seen around that time, one was the funeral home, where he attended several appointments.

Blix moved the picture into the light from the window and looked at it more closely. Elisabeth Eie had light-blue eyes and long, curved eyelashes. Thin, arched eyebrows and a prominent, powerful nose. Her mouth was half open. In the picture, it looked like she was gasping.

He jumped when the phone rang.

Again, an unknown number.

Blix replied immediately, stating his full name this time.

‘You found it,’ the gravelly voice said.

Blix went to the window and glanced out. ‘Who are you?’ he asked.

‘You think I’m just going to tell you like that?’

‘You said you wanted to confess.’ 30

‘That’s true,’ the man said, as if he was surprised at himself. ‘I did say that.’

‘I don’t work for the police anymore,’ Blix said.

‘I know.’

‘You’ll have to take this up with them.’

‘No.’The man dismissed the idea. ‘This is between us.’

Blix thought for a moment.

‘Was it you who wrote the letter back then?’ he asked. ‘The envelope with my name on it?’

No answer.

‘Is the picture real?’ Blix continued.

‘Does it not look real?’ The man on the other end seemed taken aback.

Blix didn’t answer.

‘I took it the morning I killed her,’ the man said.

Blix took a sharp breath in.

‘Why did you do it?’ he asked. ‘Why did you kill her?’

The answer came without a second’s pause: ‘Because she deserved it.’

‘Why?’ Blix repeated. ‘What had she done?’

Silence on the other end.

‘Who are you?’ Blix pressed. ‘What’s your name?’

He heard a sound somewhere on the other end, behind the silence, but was unable to identify it.

‘How did you know Elisabeth Eie?’

The man still didn’t answer.

‘How did you kidnap her?’

No response.

‘Where … ’ Blix had to clear his throat again. ‘You say you want to confess,’ he said, trying a new approach. ‘But you’re not telling me anything.’

‘Oh, I think I’ve told and shown you quite a lot,’ the man eventually retorted.

Blix flipped the picture over. ‘What do the crosses mean?’ he asked.

‘I can tell you that later,’ the man replied. ‘If necessary.’ 31

‘What do you mean?’

No answer.

‘Why are you coming forward about this now?’ Blix continued. ‘And why is it so important for you to confess to me exactly?’

The man remained silent.

‘Are you the one who’s been following me?’

Silence. A long silence. The thought of the man in the green raincoat made Blix feel clammy.

‘I saw you earlier today,’ Blix said. ‘You saw me too – that’s why you ran. Into the underground.’

He didn’t deny it.

‘Okay,’ Blix said and returned to the window. He realised he was getting nowhere. ‘What do you want me to do with what you’ve told me?’

‘That’s for you to find out for yourself.’

Blix took a deep breath. It was like talking to Krissander Dokken.

‘A picture won’t do,’ he said. ‘I need to know where she is.’

‘You shouldn’t just throw away what people send you, Alexander.’

‘Yes, you said that.’

‘If you hadn’t, you would have also seen the other pictures I’ve sent you.’

A chill ran down Blix’s spine.

‘What do you mean, other pictures? Do you mean other pictures of Elisabeth, or do you mean…?’ Blix swallowed. ‘Or have you sent me pictures of others … you’ve…?’

There was no answer.

The line went dead.

Blix needed a few seconds to compose himself, to run through everything he had been told. His pulse was still high when he called Nicolai Wibe’s number, but the police investigator didn’t answer. Tine Abelvik didn’t pick up either.

‘Oh, come on,’ he said irritably, and sent them both a text telling them to call him back. It’s about Elisabeth Eie, he added. I have new information.32

He took pictures of the photograph, both front and back, and sent them those too. This time, it was only a matter of seconds before Tine Abelvik called him back.

‘Blix,’ she said. ‘Hello.’ Her voice sounded tired. Drained.

‘Hello,’ he said.

‘How … are you?’

‘Did you get the pictures I just sent?’

‘Um, yes.’

Blix spent the next thirty seconds recounting what had happened. He spoke quickly, barely taking a breath.

‘Do you remember that case?’ he asked when he was done. ‘It was all we worked on for a while.’

‘Sure,’ Abelvik answered. ‘Of course I remember it.’ There was something measured about her answer, as if she hadn’t quite caught on or understood the seriousness of what he had just told her.

‘I think it’s the same guy,’ Blix went on. ‘The same one who wrote the letter that started the investigation when she disappeared.’

‘You didn’t recognise him?’ Abelvik asked. ‘I mean – had you heard his voice before?’

Blix shook his head. He had tried but failed to place it.

‘His voice was distorted,’ he explained.

Abelvik hesitated a moment.

‘Okay,’ she said. ‘We have to analyse the photo and see if we can verify it.’

‘It seems genuine to me,’ Blix said. ‘Why would anyone make up something like this?’

‘That whole thing with the anonymous letter – it was widely reported in the media at the time,’ Abelvik replied. ‘You were the face of the investigation, before everything else happened. You’re even more well known now. Celebrities often attract unwanted attention, often from people with no perception of reality.’

Blix wasn’t sure if he had heard her right. ‘You have to take this seriously,’ he protested.

‘We will,’ Abelvik assured him. ‘But what’s most likely here – that a 33murderer has suddenly decided to come forward and confess, or that this person is … a little muddled?’

They might not be mutually exclusive, Blix thought.

‘So what are we going to do?’ he asked. ‘Nothing? Should we just wait and see what happens or…?’

‘I’ll send a car,’ Abelvik answered. ‘We’ll come pick up the photograph.’

Some random patrol officer, Blix thought. She didn’t want to come herself.

‘I can bring it in,’ Blix said. ‘It’ll be easier. Faster too.’

‘You needn’t do that,’ Abelvik responded. ‘Stay home for now.’

Blix looked down at Terry, who was staring up at him innocently.

‘Okay,’ he said with a sigh. ‘How … ’

Again he stopped himself. He didn’t want to know how she was. He didn’t want to know how any of them were.

‘Talk soon then,’ he said instead. And hung up.

With a forceful movement, he slammed the phone back down on the kitchen table. Terry stood up, as if in protest at the sudden loud noise.