9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

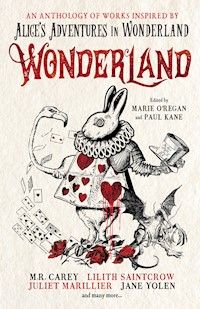

From the greatest names in fantasy and horror comes an anthology of stories inspired by Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. Join Alice as she is thrown into the whirlwind of Wonderland Within these pages you'll find myriad approaches to Alice, from horror to historical, taking us from the nightmarish reaches of the imagination to tales that will shock, surprise and tug on the heart-strings. So, it's time now to go down the rabbit hole, or through the looking-glass or… But no, wait. By picking up this book and starting to read it you're already there, can't you see? Brand-new works from the best in fantastical fiction M.R. CAREY MARK CHADBOURN GENEVIEVE COGMAN JONATHAN GREEN ALISON LITTLEWOOD JAMES LOVEGROVE L.L. McKINNEY GEORGE MANN JULIET MARILLIER LAURA MAURO CAT RAMBO LILITH SAINTCROW CAVAN SCOTT ROBERT SHEARMAN ANGELA SLATTER CATRIONA WARD JANE YOLEN RIO YOUERS

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Also available from Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Marie O’Regan and Paul Kane

Alice in Armor

Jane Yolen

Wonders Never Cease

Robert Shearman

There Were No Birds to Fly

M.R. Carey

The White Queen’s Pawn

Genevieve Cogman

Dream Girl

Cavan Scott

Good Dog, Alice!

Juliet Marillier

The Hunting of the Jabberwock

Jonathan Green

About Time

George Mann

Smoke ’em if You Got ’em

Angela Slatter

Vanished Summer Glory

Rio Youers

Black Kitty

Catriona Ward

The Night Parade

Laura Mauro

What Makes a Monster

L.L. McKinney

The White Queen’s Dictum

James Lovegrove

Temp Work

Lilith Saintcrow

Eat Me, Drink Me

Alison Littlewood

How I Comes to be the Treacle Queen

Cat Rambo

Six Impossible Things

Mark Chadbourn

Revolution in Wonder

Jane Yolen

About the Authors

About the Editors

Acknowledgements

Copyright Information

Coming Soon From Titan Books

Also Available From Titan Books

AN ANTHOLOGY

Also available from Titan Books

Cursed: An Anthology of Dark Fairy Tales (March 2020)

Dark Cities: All-New Masterpieces of Urban Terror

Dead Letters: An Anthology of the Undelivered,

the Missing, the Returned…

Exit Wounds

Invisible Blood

New Fears

New Fears 2

Phantoms: Haunting Tales from the Masters of the Genre

Wastelands: Stories of the Apocalypse

Wastelands 2: More Stories of the Apocalypse

Wastelands: The New Apocalypse

Print edition ISBN: 9781789091489

Electronic edition ISBN: 9781789091496

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: September 2019

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

‘Introduction’ Copyright © 2019 Marie O’Regan & Paul Kane

‘Alice in Armor’ Copyright © 2019 Jane Yolen

‘Wonders Never Cease’ Copyright © 2019 Robert Shearman

‘There Were No Birds to Fly’ Copyright © 2019 M.R. Carey

‘The White Queen’s Pawn’ Copyright © 2019 Genevieve Cogman

‘Dream Girl’ Copyright © 2019 Cavan Scott

‘Good Dog, Alice!’ Copyright © 2019 Juliet Marillier

‘The Hunting of the Jabberwock’ Copyright © 2019 Jonathan Green

‘About Time’ Copyright © 2019 George Mann

‘Smoke ’em if You Got ’em’ Copyright © 2019 Angela Slatter

‘Vanished Summer Glory’ Copyright © 2019 Rio Youers

‘Black Kitty’ Copyright © 2019 Catriona Ward

‘The Night Parade’ Copyright © 2019 Laura Mauro

‘What Makes a Monster’ Copyright © 2019 L.L. McKinney

‘The White Queen’s Dictum’ Copyright © 2019 James Lovegrove

‘Temp Work’ Copyright © 2019 Lilith Saintcrow

‘Eat Me, Drink Me’ Copyright © 2019 Alison Littlewood

‘How I Comes to be the Treacle Queen’ Copyright © 2019 Cat Rambo

‘Six Impossible Things’ Copyright © 2019 Mark Chadbourn

‘Revolution in Wonder’ Copyright © 2019Jane Yolen

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Introduction

MARIE O’REGAN and PAUL KANE

Wonderland.

That one word conjures up all kinds of mental images, from the tea party with the Mad Hatter to the grinning Cheshire Cat, from the White Rabbit to the giant chess game and the Queen of Hearts. And Alice, of course. Always Alice.

Ever since their publication back in 1865 and 1871, Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (originally called Alice’s Adventures Under Ground) and its follow-up Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There have captivated readers of all ages, providing the source material for countless movies and TV shows. Beginning with the silent adaptations of 1903 and 1910, by directors Cecil Hepworth and Percy Stow, and Edwin S. Porter, then carrying on through the TV incarnations of George More O’Ferrall in 1937 and 1946… From the classic and beloved Disney animated version of 1951 to, most recently, the Tim Burton takes of the twenty-first century, starring Mia Wasikowska in the title role, our obsession with this mythos seems to know no bounds.

Alice’s adventures have been turned into a ballet, countless comic strips (we’d highly recommend picking up Dynamite Entertainment’s The Complete Alice in Wonderland), they’ve inspired parodies such as The Westminster Alice, an opera, a popular song by Jefferson Airplane, a theme-park attraction (based on the Disney version) and even video games! References to—and the influence of—the original works can be felt across the board, and our interest extends as much to the story behind Wonderland as it does to the study of the place itself.

In terms of fiction, novels inspired by the works started appearing as early as 1895 with Anna M. Richards’ A New Alice in the Old Wonderland, and have continued right up to the present with interpretations such as A.G. Howard’s Splintered trilogy, The White Rabbit Chronicles from Gena Showalter, and Christina Henry’s The Chronicles of Alice.

The originals are very special stories that have stayed with us both since childhood, and which have subsequently led to putting together this anthology you now hold in your hands. But, of course, if you are going to gather a range of tales that also take as their inspiration the world of Wonderland, including drawing on the real-life circumstances surrounding its creation, then you have to be sure you’re doing something very different from what has gone before… not easy when you consider just how much of it there has been. Thankfully, the talents contributing to Wonderland are very special themselves, and their unique approaches have resulted in some of the best fantastical fiction we’ve ever read! Within these pages you’ll find poetry by Jane Yolen—and the imagination on display here would put some novels to shame—while Jonathan Green uses the “Jabberwocky” poem as the jumping-off point for his story. There are historical approaches to Alice from the likes of Juliet Marillier, Genevieve Cogman and L.L. McKinney (this takes place in her own Alice-inspired monster-hunting A Blade So Black universe). There’s even a Wild West tale from Angela Slatter and a story by Laura Mauro which presents us with a very different Wonderland, inspired by Japanese folklore.

Authors such as Alison Littlewood, Cavan Scott and Catriona Ward make the more outlandish elements their own, while James Lovegrove draws on the supernatural for his entry. Cat Rambo takes us to a part of Wonderland we haven’t seen before and Lilith Saintcrow gives the mythology a science-fiction spin. The nightmarish reaches of the imagination are the breeding ground for M.R. Carey’s visions, while Robert Shearman, George Mann, Rio Youers and Mark Chadbourn’s tales have a deep-seated emotional core which will tug at the heartstrings as well as shock and surprise.

So, it’s time now to go down the rabbit hole, or through the looking-glass, or… But no, wait. By picking up this book and starting to read it you’re already there, can’t you see? You don’t need to do a thing because it’s already surrounding you. You’re not late at all; it’s perfect timing, in fact! You’ve already begun your journey of exploration. You’re already in the place that they call…

Wonderland.

Marie O’Regan and Paul Kane

Derbyshire, 2019

Alice in Armor

JANE YOLEN

She dashed from the house,

Reverend Dodgson lingering at the door.

Never again. Never again, she thought.

She knew he would not follow.

He was too timid for the chase.

She found the armor

where she’d stashed it, by the old hedge.

The hole in the root, unused for years

still gaped like a giant’s mouth.

That armor had twice served

as one of the costumes

she wore—then un-wore—

for the old don’s photographs.

She slipped into it, feeling a bit

like a sardine in a tin, but safe,

with a bit of borrowed power.

Curiouser and curiouser, she thought,

before plopping down at the hole’s edge,

contemplating her next move.

She could hear Dodgson calling.

Her answer lay unspoken between them.

Never again. Never again.

Hands trembling, she pushed off the edge,

dropped into the hole,

going down and down and down

much heavier than before,

the armor more than doubling her weight.

She passed the familiar shelves.

Instead of empty marmalade jars,

instead of maps hung up on pegs,

she found a sheathed sword on one shelf,

a fillet knife on another, and three cannon balls.

She managed to kick the balls into the hole

and they plummeted before her.

When she finally reached bottom,

the welcoming heap of sticks and leaves,

a medal snapped perkily onto her chest plate.

A helmet topped with feathers,

red and white, settled on her head.

Spit and blood, she thought,

hefting the sword with a firm hand.

She stuck the knife into her belt.

They gave her courage for what lay ahead.

In Wonderland.

Wonders Never Cease

ROBERT SHEARMAN

1

It should go without saying, but not all the Alices survived. Some fell foul of the Red Queen, and had their heads chopped off. Some didn’t respond well to the drugs: “Drink Me”, and the Alices shrank and shrank until at last they winked out of existence; “Eat Me”, and they grew so fast that they snapped their necks on the ceiling. And many fell down the rabbit hole and never quite managed to find the bottom. They just kept on falling, and no one knows where they might have ended up.

Let’s not waste any time on them. Or any sympathy either. These are not the good Alices. These are the failures. The truth is, we wouldn’t have much enjoyed their adventures anyway. Better that we get rid of them quick, so another Alice, a better Alice, can come along.

This is not their story. Tell you what, let’s just pretend I never mentioned them. My mistake. Forget I spoke.

2

All the time she had been down the rabbit hole, and encountering all manner of weird and perplexing creatures, Alice had worried that the experience would change who she was beyond all recognition. But in fact Alice managed to confound the pressures to transform, and held on to her identity very well indeed. Yet something had to give. If Alice wouldn’t change, then something else would have to change in her place. And as she crawled out of the earth, and saw once more a daylight she feared she’d lost forever, as she smoothed the dirt from her pretty blue dress, and spat out the soil, Alice realised that the entire world had altered whilst she had been gone. There were flying machines up in the clouds and tall grey buildings scraping the sky, and all around were cars, and concrete, and computers, and cashpoint machines. And the grassy bank on which she had begun her grand adventure was now the central reservation of a roundabout off the A1.

Alice had left her sister reading, and she went to her now to ask what had happened, and what her sister made of it, and whether her sister thought it could be put right, but her sister was dead, she was dead. Alice touched her on her shoulder and she toppled over and she wasn’t breathing and she hadn’t breathed for years, and maybe she’d died of old age waiting for Alice to return, or died of boredom reading a book without pictures or conversations in it, or she’d had her head chopped off by the Red Queen, yes, that was the one. Alice touched her on her shoulder, and over she toppled, and the head toppled too, it came off nice and clean, Alice didn’t think it would have hurt a bit.

Alice had never had any family worth mentioning—just a sister without a name, and a cat called Dinah. She picked up Dinah, and put her under her arm, and set off into the city to find herself a new life.

She determined to find employment. At the job centre she was asked whether she could type, and Alice didn’t know but said yes anyway, and it turned out she could type, so that was all right. She worked in an open-plan office and she had a desk just two aisles away from the window, and Alice sometimes liked to look over the other typists’ heads and wonder what marvels the windows might reveal if only she were close enough to see through them. A man who was a clerk at the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food kept giving her lots of typing to do, some days Alice felt the only typing she got to do was his. Some days he came to her desk and stood over her even though he didn’t have any typing to give her at all. And eventually he told her he had fallen in love with her and wanted to marry her, and he was so very earnest about it that Alice didn’t feel she should refuse. She asked him his name. It was Dom.

On their wedding night Dom got into bed beside her and turned out the lights and climbed on top of her. He was there for a good minute or two, Alice didn’t quite like to ask what he was up to, she didn’t want to break that very earnest concentration of his. At last he rolled off, and panted for breath, and lay beside her, and asked her whether she had enjoyed the adventure. Alice was very polite, and said it had been no more unedifying than playing croquet with flamingo mallets, and no more uncomfortable than drowning in her own tears, and mercifully briefer than either.

And then she said, into the darkness:

“I don’t love you, Dom. I don’t think I could ever love you. What are you? You’re a talking man, but we expect men to talk, so where’s the magic in that? To meet a man who wouldn’t talk, now there would be a thing! And the thing I’ve learned about talk, is that so much of it is nonsense. To me you’re like a black hole, Dom, but not a rabbit hole, Dom, not a hole down which I can find adventure, not a hole that will challenge me or perplex me or make me think. You’re a void of a man, Dom. You’re nothing.” And she said all of this perfectly nicely, because Alice was a well-brought-up sort of girl, and had excellent manners.

It was so dark and so still that Alice thought her husband wasn’t there any longer, and that he had just disappeared, and there would be some relief in that. So she reached across to see if she could prod him, and she could prod him, his body was solid and thick and cold. Alice said to herself, “There’s nothing for it but to sleep, and see if things may be better in the morning!” And in the morning she woke up and looked to her side and Dom had gone, and his clothes were gone from the wardrobe, and his toothbrush was gone from the bathroom sink.

For a while things were much simpler. It was just Alice, and Dinah the cat, and the other girls in the typing pool. She didn’t even have to type all that much now that Dom had disappeared. But presently she began to get the funniest notion that she was never alone. There was someone else there, just out of the corner of her eye, and no matter how hard she’d turn her head she could never get a glimpse of them. And then, curiouser and curiouser, her body began to grow in different directions, and she wondered why, for she was certain she hadn’t lately drunk any strange potions or eaten any strange cakes or nibbled any strange mushrooms marked “Eat Me”. Her stomach distended and her belly button popped out and she felt very, very sick in the mornings.

Alice was always practical, and she soon realised what the matter was. “I will not let my body be used by a stranger for temporary accommodation!” she said firmly to her fat belly, and she rapped on it with her knuckles to get the occupant’s attention. “Come out of there at once!” And out it popped, she dropped her baby right there and then in the open-plan office, she had to take an early lunch break to give these new circumstances frank and considered attention. Alice didn’t know whether it was a boy or a girl, and she decided she’d think of it as a girl for the time being, and that should ever any further evidence come to light to convince her to the contrary she’d deal with it then. She chose to name it after her sister, and so didn’t name it anything at all. “How very lovely you’ll turn out to be,” said Alice to the shrieking lump of flesh, “just as soon as you’re finished!” She wasn’t quite sure that the baby would be lovely, not particularly, but she was a good-hearted girl, and she wanted to give the baby something positive to aim for.

Alice had learned all about babies during her time down the rabbit hole, and knew that the trick was to hold its arms and legs out in all directions and wait for it to turn into a pig. The baby bawled no matter how hard and long its limbs were stretched, and by nightfall Alice began to despair it would ever become a pig at all. “Just my luck the first baby I get is defective!” thought Alice. She shook it fiercely from side to side, just to see if she could shake the pigginess to the surface, and within the blur of motion she would think she could discern the baby’s nose flatten to a snout. But every time she stopped shaking and the blurring came to a halt, she’d see to her disappointment that the child stubbornly remained no more porcine than before.

“Bother!” said Alice. She took the baby home. It never stopped crying, and Alice supposed that not only was her baby broken but it also was rather unhappy. She asked Dinah her opinion, but Dinah wouldn’t reply, either because she was offended by the noise the baby made, or because she was a cat. “What to do!” said Alice. She took the baby out into the garden, and she considered each and every rabbit hole there, she wanted to find one that was just right. The rabbit hole in the very centre of the lawn was cosy and snug, and the baby would fit into it perfectly. “What adventures you’ll have!” said Alice. “I really am most jealous!”—and she dropped it into the hole, plop, and down it fell, out of sight, deep, deep, until even the bawling could no longer be heard, and Alice wondered whether her baby would ever reach the bottom.

That really ought to have been the end of it, but the next morning Alice woke to find new squirming in her stomach and new nausea in her throat. “I’m having no more of this nonsense,” Alice addressed herself sternly. She phoned up Jackie, who worked on the switchboard, and told her she wouldn’t be coming into the office today, she’d come down with a bug, and Jackie didn’t care, because Jackie was a bitch. And then she set to work on her belly, and this time the baby was reluctant to come out and she had to prise it free with a spoon. She couldn’t tell whether this was the same baby from yesterday, and that it had climbed out of the rabbit hole and crawled back inside her, or whether this baby was brand new. All she could tell was that it was just as noisy and as broken as before. This time she had to throw it down the rabbit hole quite forcefully—not to be cruel, but so the baby might take the hint.

But it was no good. No matter how fast she’d rip them from her womb, by the time she’d dropped them down the hole there’d be another baby inside squawking and wriggling and waiting to pop out. There were large babies with small heads, there were small babies with large heads, babies with hair and babies with teeth and babies with claws. Alice began to bag them up in batches of a dozen before taking them out to the rabbit hole, otherwise she was rushed off her feet going outside and inside and outside, being a mother was exhausting!

By night-time Alice was tired and out of sorts. “Come on, little one,” she said to her latest child, and she said it as kindly as she could: it wasn’t its fault it was a parasite to be disposed of. As she carried it out into the garden it occurred to Alice this one wasn’t even crying, and her heart softened towards it a little. She stared down at the rabbit hole. It was full to the brim. Out of the top poked a mass of arms and legs, some of them were still writhing—not, Alice thought, in distress, but in a matter-of-fact fashion, the way Dinah did when she was asleep and dreamed of catching mice. Alice stomped hard to flatten the babies down, but that didn’t work—she tried to wedge the baby into any cracks, but the wall of compacted infant just wouldn’t budge.

“No room!” said Alice. “No room!” And she dared at last to look down at her daughter, and she saw its little hands, and its tiny feet, and a face shining up towards Alice with hope and wonder and love. It was smiling. It was smiling, and of all the children she had ever given birth to, it was the least pig-like yet. Alice sighed. The baby sighed too, as if in imitation of its mother. And Alice held her up to her face, and gave her a kiss, and took her inside away from harm.

3

Of course, that’s not how the story really goes.

The divorce is amicable—or, at least, as amicable as divorces can ever be. Dom had plenty of money, and the maintenance he offered was fair. He insisted that Alice found another job—he said it was irksome to have an ex-wife in the typing pool, and he wasn’t going to be the one who disappeared. Why should he disappear? He would contribute to childcare. He had no interest in child custody, and made that very clear.

And Alice was happy with that. She didn’t want to share her daughter with anyone. She loved her with all her heart, and had loved her from the first moment she’d been born and the nurse had held her up to show her. As a little girl trapped down a rabbit hole she’d spent an inordinate amount of time worrying about her identity—who was Alice, what sort of person was she like? And it turned out that Alice was a mother, and she had always been a mother just waiting to happen. She went from typing job to typing job, and she never stayed for long, and she never cared—she didn’t need to make friends, because she had a little daughter at home waiting for her.

She’d wanted to name her after her sister, but people told her that that was silly, she’d have to name her something— and she’d bought a big book of names, and some of the names were very beautiful, and in spite of that she eventually called her daughter Trish.

Trish was a good girl who worked hard at school. The teachers liked her, and she never got into trouble, and she always kept away from the bad girls who hung around the bike sheds and dated older boys and smoked. Trish told her mum she wanted to go to university one day and study Psychology and Social Sciences, and Alice thought that sounded very impressive, and wondered what it was. She looked through Trish’s school textbooks, and she couldn’t make head nor tail of them. There were no pictures or conversations, and what was the use of a book without pictures or conversations?

Alice watched as her daughter grew up, and how every step took her further away. She was pleased that Trish was clever, but did she have to be so clever, and so much cleverer than Alice? The way she talked, using long words she knew Alice wouldn’t understand—the way she gave that sad sideways tilt of the head when Alice asked her to say everything again more simply and slowly. Trish was patient, but Alice didn’t want her daughter being patient. Trish was kind, but who wants the person you love to be kind to you, always having to be kind? Alice wanted to grab hold of Trish and dig her nails in, right deep into her skin, and keep her pinned down like that forever, so she would stop fast, she’d stop right there and she’d never age and the gap that was widening between them would at least never get any wider. And she wanted to burn all her Psychology and Social Sciences textbooks.

And yet, it was all right. It was all right, because whenever Alice felt small, or scared, or lonely, she would stare into Trish’s face. And Trish would smile, and the smile showed all her teeth, and it stretched wide so that it lit up her skin and flared her nostrils and made her eyes sparkle—and it was the same smile Trish gave when she was a baby. And Alice knew that the Trish she’d fallen in love with was still inside there somewhere, and she would never lose her, not really.

One day Trish said, “It’s my birthday soon. And there’s something special I would like.” And Alice said yes, yes, anything, of course she’d give her anything. And Trish smiled, and the smile was a little shyer than usual, so Alice knew this had to be something she really wanted. Trish said, “May I have a rabbit hole, all of my own?” Because it turned out that all the other girls had rabbit holes, rabbit holes were all the rage—Wendy had got a rabbit hole, and so had Brenda, and so had Cath. Alice felt her heart sink, because weren’t rabbit holes terribly expensive? And maybe Wendy’s parents and Brenda’s parents and Cath’s parents had lots of money and it didn’t matter to them, and Trish said it needn’t be a very big rabbit hole, it didn’t even have to be the latest model. She just wanted what the other girls had. Couldn’t she feel normal, just for once? Alice had often wondered too what it must be like to feel normal. She said she’d try. She said she’d find the money somehow. Even if she had to work longer hours at the office, even if she had to take out a loan. And Trish suggested they could ask Dad for help, and Alice said they needn’t go that far.

Alice asked the accounts department whether she could have next month’s pay packet early, and the woman behind the big desk took pity on her, she had a teenage daughter too. And Alice trawled through all the small ad magazines looking for rabbit hole bargains, and at last found a second-hand rabbit hole on eBay. She pulled a sickie from work the day it was delivered, whilst Trish was still at school, and they set it down where she told them, right in the centre of the garden lawn. And it was a little smaller than the ad had suggested, and the sides were chipped, but Alice knew Trish would love it anyway. And she decided she’d do it up nicely, she’d go down it and take banners, and glitter, and a big birthday cake. No, even better, she’d buy lots of party food, she could throw a birthday party for Trish in her new rabbit hole, just the two of them! Not so much mother and daughter but best friends—sandwiches and sausage rolls and Kettle Chips and cheese-and-ham quiche. And as Alice fell down the hole she began to wonder whether she’d made a mistake with the food, was Trish still going through her vegetarian phase? She said to herself, “Does Trish eat quiche? Does Trish eat quiche?” And sometimes, “Does quiche eat Trish?” For, you see, as she couldn’t answer either question, it didn’t much matter which way round she put it.

She worked all afternoon making the rabbit hole the very best it could be. When Trish came home she greeted her at the door with a big hug, and told her she had a surprise for her, and as she led her out to the garden she was skipping from foot to foot, it was hard to tell who was the most excited! They went down the rabbit hole. They reached the bottom. Trish looked around. And right away Alice could see she’d made a mistake—the banners were too much, “Happy Birthday Baby Girl!” No one wanted to be called a baby when they were fifteen. The colours were too bright, it was all loud pinks and wild oranges. And the cake was decorated with cartoon animals, a Dormouse and a Mock Turtle and a Snark. Alice asked whether she liked it, and Trish tilted her head to one side and did the kind and patient thing. “You’ve tried so hard!” And Alice had tried hard, so it was nice that Trish had noticed, but it somehow wasn’t quite the answer she’d been hoping for.

Trish had a single slice of quiche. She ate it slowly. Alice had some quiche too. “The hole’s bigger than it looks,” enthused Alice. “The banners are getting in the way.”

“Yes.”

“We just need to take down the banners. And, look, see there in the corner, there’s a tiny door! Too tiny to fit through, or so you might think!”

“Yes, I see the door.”

“But there’s probably a solution somewhere. And, what’s this on the table? A bottle marked ‘Drink Me’!”

Trish confirmed that she’d seen the door, and she’d seen the bottle, and she’d got the general idea.

“The adventures that are in store for you! For us, because I could come too, if you like! I don’t mind. Shall we drink together, shall we see what’s behind the door?”

“Maybe later,” said Trish. “I think I’d like to try it out by myself first. Would that be all right?”

“Of course,” said Alice, and tried not to sound disappointed. “Do you want me to wait here, or, or shall I go back to the house, or, or…?”

“Go back to the house.”

“Of course,” said Alice.

In the sitting room Alice waited all alone for her daughter to return. She tried to wait with Dinah, but Dinah was old now, and didn’t like people, and when Alice put her on her lap she struggled off and spat.

She wondered what Trish would make of the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party! Or whether she would solve the riddle of the raven and the writing-desk. Or whether she would survive her encounter with the Red Queen—but Alice supposed she would, because after all Alice had survived it, and Trish was far better and far cleverer than Alice was.

And she wondered what sort of Trish there’d be at the end of it all—because sometimes it seemed to Alice that her own little adventure down the rabbit hole had been the most formative part of her entire life, and that everything that had ever happened before had been leading up to it, and that everything that had happened since had been leading away, and that maybe it was the only thing that had ever defined her and made her important and made her real. She couldn’t guess how long Trish’s adventure would take, but she determined to wait for her, even if Trish were gone years and years, she’d wait the rest of her life if necessary. Trish came back a little over half an hour later. “Oh, that was quick,” said Alice. “Did you have fun?”

“Mum,” said Trish, “we need to talk.” And Trish looked so sad and so grown-up, and told Alice that she wanted to move out and live with her father instead. “Just for a while,” added Trish. “Not forever, probably.”

“Oh, my poor dear,” said Alice, and she tried to put her arms around Trish, but Trish pulled away. “But your father doesn’t want you. Don’t you see? I’m the only one who wants you. I’m all you’ve got.”

“I’ve been meeting up with Dad for a while,” said Trish. “After school, when you think I’m at hockey practice. I’m sorry I didn’t say anything. We didn’t think you’d understand.” And Trish said she had to find out who she was, she couldn’t be just a little girl forever.

“I love you,” said Alice.

“I know you do,” said Trish. And again, it wasn’t quite the answer Alice was hoping for. But then Trish smiled, and the smile was spectacular—all the teeth, flared nostrils, sparkling eyes, the full works—really, it was one of Trish’s all-time bests. So Alice couldn’t be unhappy.

And Trish went to bed, and the only thing she left behind was the smile. “I’ve often seen Trish without a smile,” thought Alice, “but never before a smile without a Trish! How absurd!” And she stayed up all night to watch the smile of the daughter she loved so much, until at last it faded and was gone.

4

Of course, that’s not really how the story goes either.

Trish never finished her Psychology and Social Sciences degree. She met a boy called Paul who was studying Geology, and they fell in love, and then both dropped out of university to get married. She didn’t even complete the first term. Alice was furious. She’d tried to argue it out over the phone, but Trish kept hanging up on her. In the end, she’d had to leave a message on the answering machine. “You’re cleverer than me. You’re better than me in every way. And I just want you to do better than I did, when the best part of my life was when I was seven years old and fell down a rabbit hole. Everything I have done since, everything, was for you. Don’t you dare fuck it all up now!”

She wrote to Dom, “Could you please behave like a responsible parent, and talk some sense into your daughter, you’re the one she listens to.” He didn’t reply.

Trish told Alice she needn’t come to the wedding unless Alice apologised. Alice told Trish she wouldn’t come unless Trish apologised first. Nohow and contrariwise! So, mother and daughter were in perfect accord, making sure neither got what they wanted. On the morning of the wedding day Alice woke early with a start, and she realised with cold horror that she was making a terrible mistake. She took a blue dress from her wardrobe, it wasn’t new but it was the best she had; she flung it into a suitcase, flung the suitcase into a car, and then flung herself one hundred and fifty miles up the M4 breaking the speed limit all along the way. She made it to the church in time to collapse into a pew and watch as Dom led her daughter up the aisle. The bride and groom exchanged rings and vows, and when it was all over and she was properly grown-up Trish turned around and saw her mother gazing at her with pride and love, and she burst into grateful tears. Alice did the same.

Alice drank a lot of wine at the reception, and that may have been the reason she started to find Dom so suddenly attractive. She almost resented him for it, he was still slim where now she was podgy, his hair rich brown and thick without a trace of her grey. He asked her to dance, and she agreed to do just the one, and they spent the next hour and a half on the dance floor, swaying slowly from side to side. And he was whispering jokes in her ear, and being charming, and Alice thought, is he flirting with me?

Dom asked if he could talk to her somewhere private. She met him outside on the patio. “I don’t think we should do this,” she said. “I think this is a big mistake.” Her heart was pounding, and she was ashamed how good that made her feel.

“I need to tell you,” said Dom. “Face to face. I’m afraid I’ve got the big C.”

It took Alice a few moments to realise what he meant. He was smiling ruefully, the way he used to do, caught out doing something wrong and knowing his charm would see him through. She’d always found it annoying until now.

“But there are things you can do…?” said Alice. Dom was shaking his head.

“Already done them,” he said. “Look. Look. It’s all right.”

And Alice found that her sympathy and her embarrassment gave way to her famous childlike curiosity. “What does it feel like?” she asked. “Knowing you’re going to die?”

Dom blinked at her, surprised. But he told her.

There was a hole in front of him, he said. It wasn’t a very large hole, but it was always there. And all he had to do was walk towards it, and he’d drop in, and it’d be over. It didn’t frighten him. The hole seemed cosy and snug. It was all right. He wasn’t going to walk into the hole just yet, but it was getting harder to sidestep. It was all right, it was all right.

Alice said, “But you look so good.” Because he did, his body lean and firm. And his wig, she could now see it was a wig, the wig suited him.

“I know,” he said, and grinned. “It’s a bugger, isn’t it?”

They could have made love that night, and maybe they should have, but neither of them quite asked the other whether they’d like to. And six months later, when Trish phoned her up, and she wasn’t crying, she was being surprisingly adult about it all, Alice wondered whether she regretted it, and couldn’t quite decide.

It was only three weeks later that Alice saw the very first hole of her own. It wasn’t where she’d expected to find one. She was in the supermarket, buying ready meals for one, and there it was right by the queue to the checkout. No, it wasn’t frightening. It wasn’t large enough to be frightening—she couldn’t have fallen down it, she’d have had a job squeezing her head through it, and all the other customers stepped over it and wheeled their shopping trolleys through it with no difficulty at all. Still, she decided to stop using Sainsbury’s for a while, and thereafter got her groceries from Tesco instead.

And after that, for the longest time, nothing—and Alice started to relax, to think the hole had been a one-off, or an accident, or a glitch. Her birthday came and went, and then Trish’s birthday, and then Christmas—and she stopped even looking for the hole, she began even to doubt she’d seen one in the first place. Which is why that spring morning when she opened the front door to set off for work and saw it there, gaping at her on the front step, she shrieked out loud the way she did. Unexpected, and so rude too, to invade her personal private property like that.

It wasn’t there when she returned home that night, and that was good. But after that Alice started to see the hole regularly—if not quite every day, then at least three or four times a week. Never in the same place, which was irritating, because it meant Alice always had to be on her guard. In the car park, on the pavement, just outside the bank. One time she found it in the lift at work, slap bang in the middle like an oily stain, and leaving her nowhere to stand—and that was annoying because she had to climb the stairs for seven floors, it quite wore her out.

Still, she wasn’t frightened. She could see what Dom had meant. Cosy and snug, the hole was always cosy and snug. And warm somehow—Alice never wanted to get close enough to check, but she detected a warmth from it anyway. Or maybe she just felt warm inside when she saw it, a happy warmth that spread through her from top to toe, like when she had a nice hot soup, like when she took a nice hot bath. It was comforting.

And yet, something was wrong. She couldn’t sleep well. Her stomach would suddenly clench painfully. She found herself short of breath, and it’d make her dizzy, and she had to stop and calm down and force air in and out of her lungs so she wouldn’t pass out. She couldn’t work out whether these symptoms were a consequence of the hole—or whether the hole was a consequence of them. Which would be worse? She didn’t want to blame the hole. She liked the hole. She’d decided to like the hole. But she thought she should take further advice.