Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

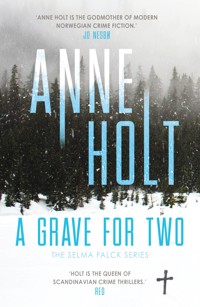

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Selma Falck series

- Sprache: Englisch

'Anne Holt is the godmother of modern Norwegian crime fiction.' Jo Nesbø Selma Falck has hit rock bottom. Having lost everything - her husband, her children and her high-flying job as a lawyer - in quick succession, she is holed up alone in a dingy apartment. That is until Jan Morell - the man who is to blame for her downfall - rings her doorbell, desperate to overturn a doping accusation against his daughter, Hege - Norway's best female skier. He'll drop his investigation into Selma, but only if she'll help... With just weeks until the Olympic qualifying rounds, clearing Hege's name, and getting Selma's own life back on track, seems impossible. But when an elite male skier is found dead in suspicious circumstances, the post-mortem showing a link to Hege's case, it becomes clear to Selma that there is a sinister web of lies, corruption and scandals lurking in this highly competitive sport. As time starts to runs out, another person is found dead, and Selma realizes that her own life is at risk... 'Step aside, Stieg Larsson, Holt is the queen of Scandinavian crime thrillers.' Red Magazine

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 609

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘Step aside, Stieg Larsson, Holt is the queen of Scandinavian crime thrillers’ Red

‘Holt writes with the command we have come to expect from the top Scandinavian writers’ The Times

‘If you haven’t heard of Anne Holt, you soon will’ Daily Mail

‘It’s easy to see why Anne Holt, the former Minister of Justice in Norway and currently its bestselling female crime writer, is rapturously received in the rest of Europe’ Guardian

‘Holt deftly marshals her perplexing narrative … clichés are resolutely seen off by the sheer energy and vitality of her writing’ Independent

‘Her peculiar blend of off-beat police procedural and social commentary makes her stories particularly Norwegian, yet also entertaining and enlightening … reads a bit like a mash-up of Stieg Larsson, Jeffery Deaver and Agatha Christie’ Daily Mirror

Also by Anne Holt

THE HANNE WILHELMSEN SERIES:

Blind Goddess

Blessed Are Those Who Thirst

Death of the Demon

The Lion’s Mouth

Dead Joker

No Echo

Beyond the Truth

1222

Offline

In Dust and Ashes

THE VIK/STUBO SERIES:

Punishment

The Final Murder

Death in Oslo

Fear Not

What Dark Clouds Hide

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Anne Holt, 2018

English translation copyright © Anne Bruce, 2018

Originally published in Norwegian as En Grav For To. Published by agreement with the Salomonsson Agency.

The moral right of Anne Holt to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 869 4

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 850 2

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 852 6

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

A GRAVE FOR TWO

THURSDAY 7 DECEMBER 2017

SELMA FALCK

If Oslo were a body, then this would be the city’s backside.

This particular apartment.

This arsehole of a living room.

The tiny room was icy-cold. The grey-brown textured wallpaper had peeled off at the corners, and the cheap laminate flooring was spattered with stains. Especially beneath the windows. Selma Falck hunkered down and gingerly dabbed at one of the dark half-moons. The crust loosened with a sticky, disgusting sound.

The tram had rattled past every fourth minute since she had started to carry in the boxes. The windowpanes were covered with frosted vinyl film, possibly to deter prying eyes. It could just as easily have been to prevent them from falling out, since distinct cracks were silhouetted behind the plastic. The room grew noticeably darker each time trams or heavy trucks passed by outside. It was growing late. Despite someone having used parcel tape to seal the cracks around the windows in addition to the plastic film, an increasingly irritating miasma of exhaust fumes assailed her nose.

The boxes were stacked in two towers by the bedroom wall. Darius squatted on top of one of these, glowering at her, crouching as if ready to pounce, his tail swinging slowly from side to side.

Selma Falck sat down on the only item of furniture in the living room, a red settee from the sixties. It had already been here, and smelled vaguely of heating oil and cheese puffs. At least she hoped it was cheese puffs. Darius suddenly arched his back and hissed angrily, but remained on top of the rickety pile on the other side of the room.

Three weeks and three days had gone by. Since then, Selma had continually caught herself glancing at the time for no good reason, as if she could make it stop with a mere look. Or preferably turn it back. This coming Monday, exactly four weeks since Jan Morell, with unaccustomed gravity, had entered her office, the deadline he had given her would expire.

There were only four days left.

She would soon be on target to lose almost everything she had ever owned.

Apart from her car, which she would never give up, and the cat that Jesso had browbeaten her into taking with her. Darius leapt down from the tower of boxes and slipped soundlessly into the bedroom. Something toppled over in there. Something had broken.

Selma closed her eyes as an ambulance speeded past. The siren tore through the wall. She clutched her ears but it did not help in the least. When she opened her senses again, Darius was standing in the middle of the living room.

His eyes glittered. His tail was still swishing belligerently from side to side. In his mouth, the animal carried a mouse with enough life left in it that its naked tail was twitching convulsively. The cat yawned, and the poor creature dropped to the floor where it lay convulsed with spasms.

Selma Falck had not wept since Saturday 13 December 1986. In six days, that would be precisely thirty-one years ago, and so she was extremely taken aback when she thought she could feel the suspicion of tears on her left cheek. It ought to be a physical impossibility. The surprise made her rise to her feet to find a mirror.

She had listed the medal from that period on eBay a fortnight ago. Not a single soul had shown a scrap of interest. The Olympic medal from two years later would probably have been a surer bet, but she had hesitated to part with it for the time being.

She was not crying, according to the mirror she found in her handbag.

It was impossible for her to live here.

She had to live here. In this rat’s nest. Or mouse’s nest, as already demonstrated, and when she peered up at the ceiling for the first time, she spotted such an enormous greyish-blue stain that she gagged.

And threw up.

The vomit matched the living room carpet.

Within the time limit Jan Morell had given her, she had managed to sell valuables to the tune of just over 13,000,000 kroner. Of that, she was now left with 23,876 kroner and 32 øre, without the slightest notion of when she would be able to earn any money again.

Fortunately no one had any idea where she was. Not Jesso, who apparently couldn’t care less anyway. Not the children, who had both made it clear that they never wanted to see her again, ever, when she had picked up some bits and pieces and filled the boxes from Clas Ohlson before driving off in a delivery van she had borrowed from the Poker Turk. None of her friends knew where she lived, although rumours of illness had apparently spread, leading to fifty-two text messages and unanswered calls in only the last couple of days. Selma Falck did not have cancer. Not as far as she knew. Inadvertently, or actually mostly in desperation, she had been forced to overplay her hand a little when incredulous partners were unable to fathom why she had so suddenly been forced to sell out. She had not used the c-word, but from what she had told them with eyes full of sorrow and a trembling lip, it was not so strange that the others had drawn the wrong conclusion. The thought made her gorge rise again. She shook her head vigorously, swallowed and decided to forget the mirror and instead find something to get rid of both the dying mouse and the green muck on the carpet.

No one must know where she was.

When the doorbell rang as she reached halfway across the living room floor, she gave such a forceful start all of a sudden that Darius arched his back again. The half-dead mouse crawled helplessly towards the door, as if it thought rescue was at hand out there. Selma padded quietly in the same direction, though she had not entirely made up her mind to open the door.

Someone was knocking loudly and impatiently.

No one knew she was here.

The doorbell rang yet again.

THE CELL

The days were no longer his own.

The room had no windows. An LED light on the ceiling was turned on twenty-four hours a day. No visible cables. Nothing he could rip out. The bed was made of cement and formed part of one wall. He didn’t even have a mattress, just some straw that had already become thoroughly matted and had started to smell.

He hadn’t been given a blanket either. Not even clothes. He wasn’t cold, it was warm in here, but he still hadn’t grown accustomed to sleeping without anything either over or under him. Dozed a little now and then.

Never slept.

Still too terrified.

He obtained water from a hole in the wall. No larger than that he could use his thumb to close it off, he guessed it to be a half-inch pipe. It dribbled continuously. Since he had no cup, he had to slurp it from the wall, where the perpetual trickle of moisture had left a yellowish-brown trail. It was starting to get slimy. Right beneath the spring, on the floor, a grate was fastened over a drain. He pissed there. Had a shit too, at the times when it was possible for him to squeeze something out. The bars on the grate were wider in the middle. Sometimes he was lucky and hit the target. Other times he had to poke at his own excrement with his foot to get rid of it. Push it, and sometimes even force it down.

Occasionally he received food, through a hatch in the metal door. Bread mostly. Bread rolls, sometimes with a spread of some kind. Never anything hot, never something that had to be served on a plate or eaten with a fork or spoon.

The days had gone by. Nights no longer existed.

The light bothered him and had stolen time. He could have been there for a week, a fortnight, or a year.

Not a year.

But a long time. A few days, at least; he should have tried to keep count of time from when he woke with no idea of where he was. He did not know why he was there. Had absolutely no clue. He screamed at the unknown figure that brought his food. Yelled and battered his fists until they bled on the grey steel of the closed door. Out there it was always silent, and the hatch was too small to discern anything except shadows on the other side.

The man must know him. It had to be a man. When he woke and found himself a prisoner, he felt pain beneath the tendons of his knee and at the top of his back, as if someone had carried him. Dragged him for a stretch too; his heels were sore. It must be a man, and he must know him.

There was nothing in here he could use to kill himself.

He wanted that more than anything; he would prefer death to this and had tried to ram his head into the wall with all the strength he could muster. Several times. All he had achieved were cuts and bruises. He had stuffed his mouth full of straw, but kept coughing it all back up again. A reflex, he assumed. He had wet the fucking grass, made it soaking wet and crammed it into his nose and throat, as hard as he could; he had almost succeeded, but just as the room went pink, his head became light and he sank down on to the bed, he had been overtaken by fits of coughing and had spewed it all up again.

Every time.

Whoever was holding him captive must know him.

Whoever had imprisoned him must know that he would choose death rather than this. And the worst thing, the very worst thing, was that each time the stranger had delivered some food, only now and then and in a pattern that was impossible to work out, that scraping, mechanical noise came from behind one wall.

It then moved closer and made the room steadily smaller.

THE SKIER

In the long series of more or less meaningless events that comprise a life, this day would be included as forgettable, no big deal, Hege Chin Morell thought. In time, she would look back on these days, these weeks that lay ahead of her and this surreal moment, and shrug with indifference.

Just a bump in the road. An annoying but surmountable obstacle on the road towards a brilliant Olympic Games in PyeongChang.

She was twenty-four years old and had decided that everything going on at present had actually not happened. It was too absurd. So obviously untrue. Something had gone wrong, and that something would be identified. The negligence would be corrected. It was simply a question of time; she’d tried to convince herself in the three days plus that had passed since she had received the incredible information.

Every minute of this hell on earth was sixty seconds too many.

The people facing her had become a greyish-blue, noisy mass. She closed her eyes gently and concentrated on picturing herself in her mind’s eye, triumphantly crossing a finishing line. A Christmas tree; a swallow dive into salt water. Her mother’s face, less distinct as the years passed, the smile that Hege could no longer completely catch except in fleeting retrospective glimpses. Mum’s blue eyes and her long, pale blonde curls, so different from Hege’s black, coarse hair that mother and daughter had woven a zebra plait of both their locks when she was little and was allowed to fall asleep in the crook of her mother’s arm once the nights grew too dark.

The most important thing of all, of course, was something she did not remember. Someone, probably her birth mother, had left her outside the absolutely correct children’s home. There was a photo of Hege, barely two months old, in a basket, with scabs in what little hair she had. She was wrapped in clean rags and had a green bear made of hard plastic for company. If she had ended up in some other place, at some other time, it would not have been Jan and Katinka Morell specifically who some months later would have brought that pale baby, suffering from eczema, home to Vettakollen in Oslo on the other side of the globe. Her biological mother, or whoever it had been, had left her early one morning under a half-dead willow tree outside the old mission station, a lucky chance in life, and little Chin would eventually learn to ski.

Her birth mother had made it worth coming into the world by abandoning her.

Four Olympic titles and almost ten thousand hours of training later, Hege knew that life brought ups as well as downs. She had learned to take them both with an equanimity that disconcerted the Norwegian public.

Hege Chin Morell knew there were great moments in life. And small ones too. Life was a chain of strong and weak links, of good and bad, of apathy and historic occasions and everything that existed between birth and death. The chain was long, and this particular moment, this absurd press conference, would just have to be endured. Hege had to stay on her feet, and she straightened her back yet another notch at the thought.

Something was completely wrong, and it was going to be cleared up.

She opened her eyes again and stared at a point high above the heads of the almost forty assembled journalists and photographers. Four serious men sat lined up beside her, three of them with hands folded and downcast eyes. The table was covered in a dark-blue tablecloth that matched her sweater, a garment that for the first time in six years was stripped of the sponsor’s name. Even the manufacturer’s logo was covered with a piece of tape. The usual fruit bowls, smoothie bottles and bottled water, that as a rule were strategically laid out on the table to be captured by the camera lenses, were conspicuous by their absence too. A solitary, nameless jug sat on the tablecloth. Only Hege had been favoured with a glass.

It was empty.

An intense tumult, filled with speculation, had suddenly ceased the moment she entered. The cameras zoomed and clicked, some people went on whispering, but the President of Norway’s Cross-Country Skiing Federation, Bottolf Odda, did not have to raise his voice when he fiddled with the microphone and cleared his throat.

‘Welcome to this press conference,’ he said. ‘We’ll come straight to the point.’

A photographer tripped over someone else’s leg and sprawled his full length. The president paid no attention to him whatsoever.

‘The reason Norway’s Cross-Country Skiing Federation has called this conference is that Hege has had …’

He swallowed.

‘A situation has arisen,’ he began again. ‘Earlier this autumn, Hege Chin Morell gave a drug test sample that has proved positive.’

Now even the cameras fell silent.

‘Which must be a mistake,’ the cross-country skier herself said loudly. ‘I haven’t taken drugs of any kind. There must be something wrong with the tests.’

The photographers went berserk again.

THE FATHER

The stairway smelled indefinably dirty. An earthy odour combined with heavy traffic, Jan Morell thought as he waited for someone to open the door.

He thought he could hear sounds, but it was difficult to know whether they came from the apartment or from the noisy city outside. He was tempted to put his ear to the door. The two uneven, apparently sticky, stripes of indeterminate colour that ran diagonally across the timber deterred him from doing so.

It had been unusually difficult to track down the address. That sort of thing seldom took more than half an hour. Jan Morell’s private detective, or security consultant as was stated on his payslip, had spent a day and a half laying his hands on a Norwegian Turk in Ensjø. The guy ran a car wash and repair workshop in an obscure establishment by day and a poker den by night. He had been obstinate, the brief note said. Jan Morell preferred not to know what the security consultant had done next. He turned a blind eye. The main point of the report was that Selma Falck had been permitted to rent this apartment for three months for next to nothing. Strictly speaking, it was really a loan. The Turk was a former, and obviously extremely grateful, client of hers.

Exactly like Jan Morell. If he wasn’t especially grateful these days, he was at least decidedly former.

No one opened up.

Jan Morell thought he heard a cat meow. He hammered loudly on the filthy door and rang the doorbell again. Now he heard footsteps.

Someone inside touched the door handle. The security chain rattled. In a slender gap between the door and the frame, Selma’s right eye and the corner of her mouth came into view.

She said nothing. Just stood there, as if she needed time to comprehend that he had found her. He glanced down. A cat’s face, he concluded. The animal looked as if it had been involved in a head-on collision: its nose was like a flat button just below its ice-blue, over-large and fairly prominent eyes.

‘Open up,’ he said brusquely, nudging the door with his elbow. ‘I have an offer you can’t refuse. One last, substantial wager.’

Resolutely, he shoved open the door and strode inside.

THE TUBE

Hege was at home alone. In the small cul-de-sac outside the house in Vettakollen, behind a tall hedge of Serbian spruce, a pack of journalists and photographers had set up camp. Earlier that evening she had heard them and their vehicles, left with the engines running. The police came. Called by the neighbours, she assumed. The photographers, who had squeezed through the hedge and come terrifyingly close, were shown off the premises by four uniformed men with barking dogs.

It would soon be ten p.m.

Her father had driven her home after the press conference. Neither of them had spoken a word. They had parked at their neighbour’s house further away and walked along an icy footpath to their own back garden before entering through the patio doors. Once inside, her father had remained tight-lipped. He checked all the entrances twice over before he stopped, took her hands in his and said: ‘I’ll put everything right.’

With emphasis, as if there were a full stop after each and every word. Then he dashed off out again the same way they had come.

This was what he was like. He was someone who put things right. He wished more than anything else in the whole world that someone would put things right. Clear up a horrendous misunderstanding. Find the mistake. Find five mistakes or ten or however many there were that had convinced Anti-Doping Norway that she was a drugs cheat. That she had used an anabolic steroid that right now she couldn’t even remember the name of, even though she had read their letter over and over again for three days in a row and anyway, knew of it from before.

Hege wanted someone to put things right, but on this particular evening she wished her father hadn’t left. That someone had been there with her. Someone other than Maggi, who presumably sat in her apartment in the basement watching Polish TV.

She walked through the almost pitch dark rooms. Her father had drawn all the curtains, thoroughly and systematically, before he left. Switched on the odd lamp that he had flicked off again on his second round. Hege stopped in front of the fridge. Opened it. She hadn’t eaten since breakfast, but didn’t want anything. Nothing except for her father to come home.

And that her mother would rise from the dead.

And that someone from Anti-Doping Norway would ring the doorbell with a broad smile and apologize for the dreadful misunderstanding. She certainly had not given a positive drugs test and would have to forget the terrible scene in front of the press corps when she managed to hold back the tears until her father had led her through a maze of corridors down to the basement car park. Someone else had driven out in her father’s Mercedes with the smoked glass windows to fool the journalists for long enough to enable the two of them to follow unnoticed in a borrowed Honda.

She quickly slammed the fridge door shut again.

It was four days since the World Cup race in Lillehammer. She had been knocked out in the semi-final of the classic sprint, but won the skiathlon the next day. Usually she got a lift with someone for races in Norway and Sweden. Teammates or coaches. Physiotherapists or even the national team doctor. This weekend, however, she had driven herself. On her own, in order to listen to an audiobook.

She had almost finished Elena Ferrante’s fourth novel.

It was always Maggi who packed for her. Packed and unpacked her travel bag. Maggi washed the clothes as well. The home help had been with them since Hege’s mother had died, and on the whole attended to most of the chores she and her father found tedious. Changing the bedclothes. Cleaning. Tidying. Preparing food. Following strict instructions, certainly; a dietician, commissioned by her father, had put together an all-year diet Hege stuck to as if her life depended on it.

And it did, of course, in a sense.

It was a matter of optimizing the possibility of winning, as her father said.

Since Hege had collapsed into bed when she came home on Sunday evening, and then woke to the news that she had failed a drugs test, she had not noticed that her bag had been emptied, the contents washed and everything put back in place. In the following days, Maggi had sneaked around like a kind, but deferential and almost invisible, ghost.

Hege ran down the stairs, taking three steps at a time. She dashed into her own room and flung open the double doors of her wardrobe. The light came on automatically. On one side of the seven square metres of storage hung her training gear. It was impossible to say if anything was missing, but the bag was empty and in the right place on the floor beside the bathroom door. She let her fingers slide across the row of hanging clothes. Stopped and tugged at a sleeve. She had worn that jacket on Sunday.

For a moment she stood deep in thought.

There were the pull-on trousers she had packed at the bottom of the bag; the zip was faulty and needed to be fixed.

Everything was here. Maggi had done her job, as Maggi always did whatever she had to. The big toiletry bag, with extra room for her carefully measured asthma medications, should be placed in the top drawer under the bathroom basin. She only used it when travelling. It contained everything she needed, and lest she forget anything on a trip, she had a double set of everything. Hege opened the door into her own bathroom and pulled out the drawer. The toiletry bag was where it should be. She picked it up, placed it on the counter beside the basin and opened it.

Deodorant. Approved by the national team’s doctor. Make-up. Approved by the national team’s doctor. Toothpaste, hairbrush in a plastic bag, mint dental floss. The perfume her father had given her at Christmas, examined and approved by all the expertise with which her father always surrounded himself. Three inhalers. A packet of Paracet, unopened.

She stacked the items one on top of the other in the wash-hand basin. The toiletry bag was soon empty.

The unfamiliar tube lay at the very bottom. In a rectangular white box with green and black writing. Together with some sort of ‘no admittance’ mark in red, fairly large, stamped above the words ‘BANNED SUBSTANCE’ in black.

TROFODERMIN was the name of the medication.

Hege dropped the box on the floor.

Her ears were ringing. She tried to blink away the black dots dancing in front of her eyes. She grabbed her inhaler, applied it to her mouth, pressed and took a deep breath.

Open-mouthed, she continued gasping for breath.

She was well aware what Trofodermin was.

On the other hand, she had no idea how the package had ended up in her toiletry bag, in her luggage, after a successful World Cup weekend in Lillehammer.

Absolutely not the foggiest, and the world had stopped spinning.

THE GLASS PALACE

He was freezing.

Arnulf Selhus knew it wasn’t cold in the large room. The temperature and air quality were controlled by an installation so modern that only two years ago, when the king had formally opened the building, it was the only one of its kind in the world. All the public rooms were set at 20.00 degrees Celsius, right down to the decimal point. Nevertheless his teeth were nearly chattering.

Sølve Bang apparently noticed nothing.

‘This is a scandal,’ he shouted. ‘A scandal we simply can’t afford, Arnulf. Taking drugs is completely unacceptable!’

The platitudes sent a shower of fine spittle across the oak table.

‘Of course,’ Arnulf Selhus said apathetically, covering his face with his hands. ‘You’ve said that several times now. But what the hell can we do, eh? Kill the young girl?’

‘That might be an idea,’ was the quick riposte.

Sølve Bang stood up just as abruptly as he had dropped into the pale-blue designer chair only two minutes earlier.

‘She’s never been really popular. That goes without saying. She’s far too …’

‘Give over. Cut it out.’

‘Well, she’s certainly created a catastrophe now. She’s responsible. Someone is responsible. Nothing here in this world happens without someone being responsible, Arnulf. It’s a betrayal. A dreadful betrayal of us all. Of the Federation, of the other team members, of …’

‘Of you,’ Arnulf mumbled into his own hands, so softly that he hardly heard it himself.

‘What did you say?’

‘Nothing. But now you should really calm down. Strictly speaking, this doesn’t have anything to do with you, Sølve. We have procedures for this. Protocols. Rules.’

‘Rules? Protocols?’

The small, corpulent man’s voice rose to a falsetto. He began to trot back and forth across the floor, parallel to the glass wall that on some days let the whole of the Oslo Fjord reveal itself out there. Now, as usual for the time of year, a peasouper of a fog weighed down on its huge, cold expanse.

Arnulf Selhus raised his eyes again. Sølve Bang walked with short steps, had a pendulous paunch and a nose so long that it almost touched his upper lip. His eyes, normally slightly protruding, had begun to look cross-eyed in his agitation.

He didn’t look much like a former skier.

Maybe not much like a writer, either, Arnulf thought, although admittedly writers came in all shapes and sizes.

The yellow memory stick hanging round his neck, on a narrow chain of the same material, bounced up and down on his tie as he trotted around. He continually touched it with his fingers, on hands that could have belonged to a girl. Arnulf Selhus had known this man since 1982 and had never particularly liked him. But right here and now he felt an unfamiliar, new sense of loathing.

Or fear, it suddenly struck him.

The room was filled with dread. It lurked in the corners. It hid behind the straight, pale curtains he felt an almost irresistible urge to close. Even outside the ridiculously large windows, between the dark spruce trees that flanked the car park, it looked as if an indefinable, dark-grey presence threatened to force its way in through the glass and seize him.

Arnulf Selhus had difficulty breathing deeply enough.

Sølve had enough on his plate and still noticed nothing.

That a man who had won one measly World Cup race thirty-five years ago was permitted to behave as if he owned Norwegian cross-country skiing was beyond Arnulf’s comprehension.

Sølve Bang had even managed to steamroll through this damned building, this glass monument on the slopes of Holmenkollåsen. With himself as head of the jury when the architecture competition was advertised, and later in charge of the building committee.

Many people thought when cross-country skiing had broken free from the Norwegian Ski Federation in 2008 it had been an example of sheer hubris. Arnulf Selhus among them. Classic short-sightedness as he had both thought and said at the time. The administration of cross-country skiing in the Norwegian Ski Federation had landed an exceptional sponsorship contract with Statoil, adding petrol to the flames for those who regarded cross-country skiing as the very jewel in the ice crown of winter sports. Remarkably enough, the agreement was entered into for a period of twenty years, an eternity in sponsorship terms. Alpine skiing could go its own way, was a comment muttered ever more loudly in the corridors after the deal had been struck. In truth, it was only a tiny group of adherents that bothered about Telemark skiing. Similarly with the loopy snowboard fraternity – anyway, it was populated by individuals who had never really understood the meaning of organization. Freestyle skiing was for teenagers and had barely contributed one iota since Kari Traas’s time.

Norway was cross-country skiing, and Norwegian cross-country skiing could stand on its own two agile feet.

The Cross-Country Skiing Federation was now only nine years old, and its independent status had failed to be the picnic that Sølve Bang and his many followers had anticipated.

Neither had they anticipated a top athlete being caught up in a drugs scandal.

Clapping his hands to his face, Arnulf groaned.

‘We have to talk to the sponsors,’ he said. ‘They can’t just …’

‘That’s exactly what they can do,’ Sølve snarled, taking hold of his memory stick as he approached his companion. ‘All sponsors have a drugs clause. Statoil’s is unconditional and strict. They have every right to pull the plug on us, Arnulf!’

‘We still have the state sponsorship. Lottery funds. Volunteerism. The smaller sponsors, such as MCV. We can still …’

‘Volunteerism? Do you think this … this …’

He let go of the memory stick and spread his arms.

‘Do you think the Crystal Palace was built from money raised by selling waffles? Do you think it’s the old biddies shuffling around out there …’

His slender right hand waved uncertainly in the direction of the grey windows.

‘… holding jumble sales and making hot dogs and whatever else they … Do you think it’s volunteerism that has made it possible for the NCCSF to grow to such heights? What? Do you think …’

All of a sudden he subsided on to a chair, clutching his forehead and blowing slowly out through his nose.

‘And with that unstable, incompetent cow in the Ministry of Culture the prospects for lottery funding don’t look too good either,’ he added bitterly. ‘That’s how it goes when people in here have eaten and drunk their fill and travelled business class and then …’

‘Those accounts have been buried,’ Arnulf Selhus broke in sharply. ‘Everything before 2015 has been settled by Parliament. That’s for definite. After Sochi, things don’t look so bad, and those are the accounts the world will respond to. Only those.’

Silence ensued. The fog outside grew even thicker, if that were possible. When he abruptly rose to his feet and stood facing the window, the lights down in the car park were reduced to vague cotton wool dots of lighter grey against all the darkness.

‘But let’s take one thing at a time,’ he concluded, tugging at his tie. ‘We have enough on our plate with Hege right now. And anyway, neither you nor I will be the ones to deal with this situation. I’m going home.’

He turned around again.

Sølve Bang seemed deaf to the world. He sat lost in thought, with eyes unfocused. One hand was holding the memory stick, which he clicked in and out of its cover in a nerve-wracking rhythm.

‘I’m going,’ Arnulf Selhus repeated as he headed for the door.

The other man still gave no answer. He clicked and clicked, and as Arnulf Selhus put his hand on the door handle, it dawned on him that neither of them had given a thought to how Hege Chin Morell must be feeling after the revelation.

‘Well, not as fucking awful as me, anyway,’ he muttered inaudibly as he closed the door behind him and left Sølve Bang to sit alone in the spacious conference room which King Harald – in person – had honoured with the name ‘Golden Girls’.

THE BET

‘It’s not connected,’ Selma said, pointing at the black TV screen. ‘I haven’t seen the news for ages.’

‘Well, you have a mobile.’

As Jan Morell scanned around, his expression looked as if he was standing in the midst of a landfill site. His previously narrow nose turned into a straight line.

Selma sat down on the cheese puff settee and made a gesture of invitation to indicate he should do likewise. He remained standing.

‘It’s about Hege,’ he said without making any comment on the apartment apart from a look that continued to scour the room. ‘She’s failed a drugs test.’

‘What?’

‘Anti-Doping Norway claims she’s somehow taken Clostebol. Of course, she hasn’t.’

‘Clostebol?’ Selma repeated. ‘That’s an anabolic steroid, as far as I recall?’

‘Yes, one I knew nothing about. Until three days ago. It’s obviously a misunderstanding. A mistake. Sabotage, at worst. That’s what I want you to find out.’

‘Me?’

She picked up a yellow cushion and put it behind her back before continuing.

‘You’ve given me a deadline of Monday, Jan. This Monday! I was at the bank this afternoon, so that’s already taken care of. Thirteen million kroner have been returned to your account. You’ll just have to wait for the last three. I quite simply can’t cough up any more. Give me two years for that part. I’ll also hand in my licence to practise law, as you’ve demanded. On Monday. If you think I can get to the bottom of something as complicated and serious as a drugs charge by that time, then you overestimate me.’

‘You can work without a licence.’

‘As a lawyer?’

Selma smiled joylessly, pulled out the cushion from behind her back and punched it lightly before clutching it to her chest. It had grown noticeably colder in the last hour.

‘No,’ Jan Morell said tersely, now at least turning to face her.

Until now he had been speaking into thin air. Now he sought eye contact.

‘You can never have access to other people’s money, Selma. We’ve discussed that. You can’t have a licence to practise law with your … predilection. The matter is over and done with.’

‘Then I can’t help you.’

‘Not me. You can help Hege. And you’ll do it as a consultant. Working for me.’

Selma felt her pulse race. She breathed more quietly, concentrating, and regained control.

‘That’s sheer madness, Jan. We have an agreement. One: I pay back the money.’

She used the fingers of her right hand to count on her left.

‘Two: I hand back my licence to practise law. Three: I must never gamble again. Nothing. At all. The quid pro quo is that you don’t report me. Quite a …’

Darius leapt on to the settee, circling himself soundlessly a couple of times before lying down.

‘… rough deal,’ Selma rounded off.

He opened his mouth and she held up her palms to stop him.

‘Strict,’ he nevertheless went on to say. ‘But fair.’

She placed the cushion as a buffer between her and the cat.

‘Fine,’ she said, with a note of resignation. ‘But an agreement like that makes it totally impossible for me to work for you. You’ll realize that, if you think about it.’

‘Look on it as a bet,’ he said sharply. ‘Your very last one. If you find the explanation for how and why an honest, clean, elite athlete has quite inexplicably tested positive and risks losing the greatest experience of her life, then you’ll get your money back.’

‘PyeongChang.’

‘Yes.’

‘No cure, no pay?’

‘Yes. Only then will it really be a bet. You have until the very last selection date. 24 January 2018. If you succeed, the money’s yours. Sixteen million. Many of your problems could be fixed for sixteen million kroner, Selma. Especially since three of them represent debt you have nothing to show for. If you don’t succeed, then both you and I will have wasted our time.’

‘But why me?’

Jan Morell gave a faint smile.

‘Look at yourself in the mirror,’ he said with a touch of contempt. ‘Read your own CV. If anyone is able to get to the bottom of this, it’s you. A top athlete. A top lawyer. You took on three famous drugs cases and won two of them. Into the bargain, you’re one of Norway’s most famous faces and admired role models.’

‘Former top athlete,’ she corrected him. ‘And from Monday on, also an ex-lawyer. Probably also a far less famous face. From now on, at least.’

Holding out his hand, he pretended not to hear her.

‘Do we have a deal?’

Selma got to her feet. Stared at his hand without taking it in hers. Darius jumped warily down to the floor again, with his eyes fixed on the mouse, now lying stone dead in the middle of the floor.

‘I don’t even know where to begin,’ Selma said hesitantly.

‘By coming with me,’ Jan Morell told her, retracting his hand and heading for the door. ‘You have to speak to Hege.’

Only now did he catch sight of the mouse and stopped short.

‘What kind of place is this?’ he exclaimed, taking a step back. ‘And what the hell’s that cat doing here?’

‘It’s a long story,’ Selma said curtly, circumnavigating the mouse cadaver as she went to collect her outdoor clothes. ‘I have to do something first. I can be at your place in a couple of hours.’

A swift glance at the Rolex. Yet another item she would try to keep for as long as possible, it struck her. In reserve, of course: a watch like that would fetch a good price on eBay.

‘Before midnight. OK?’

‘Yes.’

‘And …’

‘Yes?’

‘You’ll have to cover all expenses.’

Irritation, possibly anger, crossed his face.

‘Within reasonable limits,’ he finally said. ‘Do you take the job?’

‘I accept your bet. With no particular belief that I’ll be able to win. Have you considered at all that she might in fact be guilty?’

‘She’s not. I know that. Anyway, you forgot one point.’

‘What?’

‘In our agreement. Point four. You’ll provide me with written confirmation from a licensed psychologist or psychiatrist that you’re receiving treatment.’

Now Selma was the one to freeze.

‘That point will have to be deleted.’

‘Out of the question.’

She hung her jacket back on the hook. The tiny hallway was unlit. Only the open door into the living room made it possible for them to see the contours of each other’s face.

‘I’ll never consult a psychologist, Jan.’

‘Yes, you will. Ask Vanja Vegge for advice. Isn’t she a good friend of yours? If you don’t do that, I’m happy to inform you that the formal complaint is ready and waiting in my safe.’

She stared at him. Was met by a blue gaze, brimming with success, arrogance and wealth. Despite being scarcely five foot eight, Jan Morell was a man at his full height. He usually got his own way.

‘No,’ she said firmly.

‘Your choice,’ he said brusquely, putting his hand on the door chain. ‘The formal complaint will be delivered on Monday.’

The door slammed behind him.

Darius meowed.

Selma Falck hesitated for a few seconds. Grabbed her jacket and dashed out into the stairwell.

‘Jan!’

Fortunately, he had waited for her beside the mailboxes.

THE HIDING PLACE

The first thought that came to Hege, when she no longer felt she had to throw up, was to call her father. The second thought struck her before she located her phone:

What one person knows, nobody knows. What two people know, everybody knows.

It was her father’s mantra. Ever since she, as a tiny, deadly serious bundle, had been collected from China, Jan Morell had instilled in her that she should never trust anyone. No one. Except for him and Katinka, Hege Chin’s Norwegian mother.

You can never trust anyone except the people who put you before themselves. No one other than those who love you. Only Mum and I do. Remember that.

Mum had always smiled indulgently, rolling her eyes slightly, and tried to make him listen to reason. Most people were dependable, Hege should know. On the whole, people wished one another well. That was how she lived, Katinka Morell. That was what she was like, and that was how she died after a hospital blunder her widower pursued at great lengths through the legal system. Eventually receiving three million kroner in compensation. The money was invested in a trust for Hege, who was eleven years old at that time. Not that she would ever need it, as Jan Morell’s only child.

The writing on the box shone out at her. She had perched it on the edge of the wash-hand basin. It crossed her mind that she had touched it, and she picked it up with a hankie and began to rub away the fingerprints that must be all over it. The packaging fell apart, becoming flat and misshapen, and the lid opened up at one end.

The text was in Italian.

Hege had been to Italy. With the national team. At the end of August, beginning of September.

The tube itself slid out of the package and fell to the floor.

What one person knows, nobody knows.

Dad and Hege were as one. It was always the two of them. In a sense it always had been, at least after Mum’s death when the skiing had taken the upper hand for them both. They had used training to eradicate their sorrow. Tried, at least. Skated through Nordmarka in winter, ran in summer, used roller skis, treadmill, weights and a stopwatch to flee from a death neither of them had seen coming and also never succeeded in running away from.

They were two sides of the same coin.

But Dad always thought on his feet. He was so quick thinking, so fast that he always stole a march on everyone else and for that reason he was always allowed to choose the trail. He was proud, almost boastful, of being called Pathfinder as a child, when he was the best at skiing among all the youngsters in his neighbourhood, despite using old wooden skis with Kandahar bindings far longer than all the others.

He was going to do something. At once. Move heaven and earth to find out who had compromised Hege’s luggage. He would take one look at the tube of ointment, bark out some specific questions and dash to the door again. Dad always did something. Took action. PDQ and on the double.

Hege didn’t want anything to be done. She wanted the tube of Trofodermin to disappear by itself. All this should just vanish, and she picked up the tube. The lid unscrewed with a barely audible click. After turning the cap, she pierced a hole in the foil seal over the opening. She lifted the toilet seat lid and squirted the ointment down into the bluish, fragrant water. She used her finger and thumb to squeeze the tube three times from bottom to top. Carefully, to avoid getting any on her fingers. The sticky mass disappeared down into the blue void, and when it proved impossible to press out any more, she flushed three times. Vigorously deployed the toilet brush and flushed yet again.

Her breathing was steadier now.

She fetched a lighter from the small table with candleholders in the living room. Back in the bathroom, she held the packaging above the toilet bowl and set it alight. Let it burn until it singed her fingertips. Dropped it. Flushed it away.

The tube was made of metal. Perhaps it could be melted at a high temperature. In the fireplace, maybe, but none of the fires were lit now. Following a period resembling winter at the beginning of November, mild weather had set in, turning their existence grey and wet. Even up here on the heights. The fireplaces, both the one in the kitchen and the big hearth in the living room, were never used unless it was really cold. That was also a change since Mum died; Katinka Morell would even light the fire to roast marshmallows in the middle of summer.

Dad had a more practical bent.

The purpose of the fireplaces was to heat up the rooms, and now and again for decoration when they had company.

She would have to wait. Without giving much thought to what she was doing, she put down the toilet seat lid, stepped up on top of it with the empty tube in her hand and unhooked the ventilation grille. When she was younger, she had hidden her diary in here, a notebook so full of trivialities that it now lay in the drawer of her bedside table, with nothing being written for years on end. She hurriedly thrust the tube into the round duct, as far inside as possible, and put the grille back in place again. The catch had loosened, she noticed; in her early teens she had gone in there on a daily basis.

Dad thought the bathroom should be renovated. Until now Hege had flatly refused. The room would soon be completely antiquated, he argued, and something should be done in consideration for the value of the house. But there was still a bit of Mum about the bathroom, something Dad failed to notice. A heart, neatly painted in nail varnish on a tile just beside the door. Hege’s height marked on the doorframe. Lines with dates written in various pens with big exclamation marks when she’d had a growth spurt.

If the bathroom were renovated, Hege imagined, she might sneak the empty tube into the floor cement.

She gave herself a slap on the ear at the idiotic idea. This couldn’t wait. The tube would have to be disposed of as fast as possible, but in the meantime it could stay where it was. She would think of something.

What one person knows, nobody knows.

No one knew that she could have been caught red-handed with a banned medication in her toiletry bag, traces of which substance had been found in her own body. She let the water in the basin run until it was red-hot, and held her hands under the flow until they were crimson.

Maybe she had done something terribly stupid. It wasn’t really possible to ingest drugs through an ointment for wounds. But, technically speaking, of course, it was. From a formal point of view, traces of this ointment could bring her down, and the tube could be the proof she needed at least to be able to blame something. Something far less damning than systematic use of a performance-enhancing drug.

The problem was simply that she had never used that bloody cream. An even greater problem was that someone had tried to make it look as if she had done so.

She should, of course, have gone straight to Dad.

Now it was too late, and she went down to the basement to run on the treadmill.

THE DOWN-AND-OUT

He lived in a cardboard box from IKEA.

It was large and had contained a settee called Stockholm. To tell the truth, Einar Falsen lived in several boxes, of varying sizes, in four different places around Oslo.

This particular abode was situated under the Sinsen interchange and was his usual haunt during Advent. The other shacks made of cardboard, scrap wood and bushes were dotted around the wilderness region of Oslomarka, two of them pretty close to populated areas, one of them close to the Katnosa Lake. He headed there during good weather in summer and could stay there for weeks at a time. He got by on what he found. Both in the landscape and at picnic spots, it was really unbelievable what people left behind, even so far inside Marka that only really experienced hikers ventured here. One or two outdoor fanatics eventually got to know him and slipped him a sausage or a few slices of crispbread on their way home through the forest.

Approaching Christmas he settled every year beneath Norway’s busiest traffic machine. More than a hundred thousand vehicles thundered above his head twenty-four hours a day, which he found soothing. This hiding place behind the colossal piles of aggregates and boulders had belonged to him for many years now. It had seemed under threat when the Roma people made their entry into Norway in 2013. Politicians were enraged and set the cops on them. Einar Falsen was allowed to stay as soon as the young, gruff uniformed officers understood who he was. That pre-Christmas period was good, because they brought him coffee prior to repeatedly chasing the gypsies off to a series of different night shelters. Last year some of the seedy Romanians returned, but they kept a safe distance with all their bags and baggage down by the new football pitch at Muselunden.

Einar Falsen was seldom cold.

Cardboard and newspapers, an old sleeping bag, layer upon layer of clothes he regularly fished out of damaged UFF secondhand clothing containers. Aluminium foil and an enormous hat with earflaps. The sum total normally kept out the cold.

But he was hungry. It was fairly late, he thought – the rumble of heavy traffic above his head had abated somewhat. Selma should have been here by now. He pulled off his mittens and took the old mobile phone out from his chest, close to his skin, packed in an old sock wrapped thoroughly in three layers of silver paper to ensure the phone didn’t kill him.

The mobile was an old Nokia 1100, and he’d received it as a present. It contained one saved phone number, and he used it very rarely. Selma was the one who had insisted on giving him the opportunity to contact her. Cordless phones were dangerous, he was well aware of that, but Selma had guaranteed that this particular model was safer than any other. It was nonsense, of course, since in the first place mobile phones emitted cancer-producing radiation, and secondly they were under surveillance by the Norwegian security services and the CIA, one and all. After a great deal of persuasion, he had nevertheless gone along with ‘taking care of it’, as she had put it; it could hardly cause any harm when he almost never switched it on. She should have been here at ten p.m., the message confirmed. It was now twenty-three minutes to eleven.

Selma was the only one he had.

And there she came.

Einar loved the way she walked. Supple, as if she were constantly ready to break into a run. In the glow from the Maxbo billboards at the foot of the interchange and the floodlights on the football field to the north-east, he could see her nimbly jumping from one boulder to the next. They were slippery these days, he had experienced that for himself last night when he had fallen and given himself a nasty knock on the way home from a round of begging, but Selma moved like a dancer.

She was born in 1966, he knew. Fifty years old last September.

Selma moved as if she were twenty-five.

‘Hi, Einar. Sorry I’m a bit late.’

‘I’m not going anywhere,’ he said with a smile. ‘At least you came, Mariska.’

She returned his smile and began to root around in the bag she carried in her right hand.

‘Here. A fully charged power bank. Give me the empty one, please.’

Einar produced the heavy little energy supply for his mobile phone and gave it to her in exchange. Both the empty one and the full one were encased in bubble wrap and a sock.

‘And here you are,’ she said, sitting down as she unpacked a sandwich from Deli de Luca. ‘Cheese and ham with an extra dollop of red pepper. Sorry, but I didn’t have time to fill a thermos of coffee, so …’

She handed him a giant-sized cardboard beaker wrapped in napkins and sealed with tape.

‘Probably not hot any more.’

‘Doesn’t matter. What’s wrong?’

‘Wrong?’

‘Yes. You’ve been so stressed out lately. Now there’s definitely something bothering you.’

‘No, there’s not.’

‘I recognize that look of yours. Is it something at work?’

He guzzled down half the contents of the beaker without waiting for an answer.

‘No, of course not,’ she said casually as he drank. ‘Just lots to do.’

‘And the family?’

‘Absolutely fine. The kids are so busy I hardly see them. It’s only Johannes living at home these days. He’s got a lot on his plate. You know how it is.’

Einar Falsen stood up, unsteady through rheumatism and eleven years as a down-and-out. He stretched his arms up into the air with a grimace before shaking his legs, one at a time.

‘This isn’t us, Mariska. We don’t sit here lying to each other. If there are things you don’t want to talk to me about, that’s fine. But don’t tell lies.’

‘I’ve been given a case,’ she said quickly.

‘I assume you get cases all the time.’

He sat down again, on a pile of newspapers and with the rolled-up sleeping bag at his back.

‘It’s actually not as a lawyer that I’ve received this particular case,’ she said, taking a bottle of cola from her pocket. ‘I’ve to be more of a sort of … investigator, in a sense.’

‘You? Investigate? You’re a lawyer, damn it.’

Chuckling, he shook his head and sank his teeth into the sandwich.

‘What’s it about?’ he went on with his mouth full of food.

‘A drugs case.’

‘Boring.’

‘Not necessarily. It’s to do with Hege Chin Morell.’

The chewing stopped momentarily.

‘That Chinese girl? The cross-country skier?’

A slice of red pepper trailed from the corner of his mouth. It looked like a dribble of coagulated blood. He swiftly poked it in again with a finger covered in ingrown grime. Selma handed him the cola bottle.

‘She’s not Chinese, Einar. She’s Norwegian.’

‘Yeah, yeah. But originally Chinese. No surprise that she was never popular.’

‘She is popular. She’s a winner.’

‘No. She’s tolerated because she wins. Admired. That’s something else entirely. And now she’s gone and taken drugs into the bargain. Sic transit gloria mundi.’

‘She claims it’s not true. That it must be a mistake.’

‘They all do.’

He was still talking with food in his mouth. The sandwich was soon all eaten up.

‘Good,’ he said, swallowing and putting his hands back into a pair of enormous construction workers’ mittens from Mesta, black with yellow reflective stripes. ‘Thanks.’

‘They all don’t.’

‘Almost,’ he insisted, stashing the cola bottle between two rocks. ‘There aren’t many penitent sinners. Even I don’t repent. And I killed a man. With my bare hands.’

He lifted the mittens up in front of his eyes and stared almost in bewilderment at them before adding: ‘That’s far worse than taking drugs. In the eyes of other people, I mean.’

‘Well, judging by the media attention, that’s debatable.’

Selma waved her iPhone, which immediately began to light up.

‘Hey! Keep that murder weapon away from me!’

He half-rose and drew back on the large boulder. The cardboard box behind him wobbled. Selma returned her mobile to her pocket.

‘Einar,’ she said gently. ‘Where do I begin? I mean …’

Reassuringly, she patted the jacket pocket into which the phone had disappeared.

‘Switch it off,’ he ordered.

Selma complied.

‘If we assume she’s telling the truth,’ she began again. ‘Just for the sake of hypothesis. It seems incontrovertibly correct that she provided a urine sample that showed a tiny amount of the banned substance Clostebol.’

‘Sounds like a cleaning agent.’

‘Where do I start?’

‘On what?’

A police car advanced along Trondheimsveien with sirens blaring. The sweeping blue lights did not reach into the darkness beneath the bridge. The noise did, however, and they sat in silence until the vehicle accelerated towards Carl Berner and disappeared.

‘There are actually only three possibilities,’ Einar said quietly as he drank the rest of the cold coffee. ‘If we take for granted that she’s telling the truth.’

He took off the mittens and carefully broke the cardboard beaker open along the seam. He licked the dregs from the inside and folded it up neatly before tucking it into a well-used plastic carrier bag from the Rema supermarket chain.

‘First of all, there could be some mistake with the tests.’

‘That doesn’t seem to be the case. Her father, Jan Morell, you know …’

‘I know who Jan Morell is.’

‘For a man with no internet connection or fixed abode, you’re remarkably well informed, Einar.’

‘Newspapers,’ he said tersely, shifting his backside a little. ‘Great things. They’re lying about all over the place and can be used for so many purposes. Just because you get to know most things hours after everyone else, doesn’t mean you don’t know.’

Selma smiled. Einar liked to see Selma smile. He persuaded himself that she kept this particular smile just for him, a mixture of admiration and love he had once encountered from so many people, but after all that had happened, now only had the strength to accept from her and her alone.

‘Hege learned of the case on Monday,’ Selma said. ‘Her father has used the time since then wisely. With his money and energy a lot can be resolved PDQ. It doesn’t seem that there’s anything wrong with the tests.’

‘Then we’re down to two scenarios. Either she ingested this substance by accident, through her own fault or someone else’s, or else she’s been sabotaged.’

Silence reigned between them.

Einar Falsen felt a headache coming on. It was just his luck. After four good days when only his rheumatism had grumbled a little, especially his left hip, it was as if barbed wire was tightening around his head. It must be that blasted phone she always had with her, even though she had switched it off.

‘An accident is the more likely scenario,’ he said, closing his eyes. ‘Sabotage the more exciting.’

She did not reply.

‘You have to start by freeing yourself,’ he said slowly.

‘What do you mean?’