2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

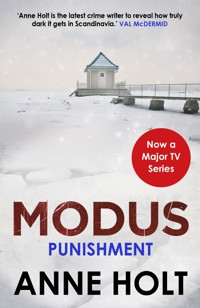

A serial killer is on the loose, abducting and murdering children in a way that confounds the police, before returning the child's body to the mother with a desperately cruel note: You Got What You Deserved. It is a perplexing and terrible case, and Police Superintendent Adam Stubo is in charge of finding the killer. In in a desperate bit to get some answers he recruits legal researcher Johanne Vik, a woman with an extensive understanding of criminal history. So far the killer has abducted three children, but one child has not yet been returned to her mother. Is there a chance she is still alive? And can the pair solve the case in time?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

PUNISHMENT

ANNE HOLT spent two years working for the Oslo Police Department before founding her own law firm and serving as Norway’s Minister for Justice during 1996–1997. Her first book was published in 1993 and she has subsequently developed two series: the Hanne Wilhelmsen series and the Johanne Vik series. Both are published by Corvus.

ALSO BY ANNE HOLT

THE JOHANNE VIK SERIES:PUNISHMENTTHE FINAL MURDERFEAR NOT

THE HANNE WILHELMSEN SERIES:THE BLIND GODDESSBLESSED ARE THOSE THAT THIRSTDEATH OF THE DEMONTHE LION’S MOUTHDEAD JOKERWITHOUT ECHOTHE TRUTH BEYOND1222

PUNISHMENT

Anne Holt

Translated by Kari Dickson

First published in the English language in Great Britain in 2009 by Sphere, an imprint of Little, Brown Book Group.

This edition published in 2011 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Originally published in Norwegian as Det som er mitt in 2001 by Cappelen.

Published by agreement with the Salomonsson Agency.

Copyright © 2001, Anne Holt.Translation copyright © 2007, Kari Dickson.

The moral right of Anne Holt to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. All characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Ebook ISBN: 978-0-85789-464-9Paperback ISBN: 978-1-84887-613-2

Printed in Great Britain.

CorvusAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26-27 Boswell StreetLondon WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter 15

Chapter XVI

Chapter XVII

Chapter XVIII

Chapter XIX

Chapter XX

Chapter XXI

Chapter XXII

Chapter XXIII

Chapter XXIV

Chapter XXV

Chapter XXVI

Chapter XXVII

Chapter XXVIII

Chapter XXIX

Chapter XXX

Chapter XXXI

Chapter XXXII

Chapter XXXIII

Chapter XXXIV

Chapter XXXV

Chapter XXXVI

Chapter XXXVII

Chapter XXXVIII

Chapter XXXIX

Chapter XL

Chapter XLI

Chapter XLII

Chapter XLIII

Chapter XLIV

Chapter XLV

Chapter XLVI

Chapter XLVII

Chapter XLVIII

Chapter XLIX

Chapter L

Chapter LI

Chapter LII

Chapter LIII

Chapter LIV

Chapter LV

Chapter LVI

Chapter LVII

Chapter LVIII

Chapter LIX

Chapter LX

Chapter LXI

Chapter LXII

Chapter LXIII

Chapter LXIV

Chapter LXV

Chapter LXVI

Chapter LXVII

Chapter LXVIII

Chapter LXIX

Author’s postscript

PUNISHMENT

The ceiling was blue. The man in the shop claimed that the dark colour would make the room seem smaller. He was wrong. Instead the ceiling was lifted, it nearly disappeared. That’s what I wanted myself, when I was little: a dark night sky with stars and a small crescent moon over the window. But Granny chose for me then. Granny and Mum, a boy’s room in yellow and white.

Happiness is something I can barely remember, like a light touch in a group of strangers, gone before you’ve had a chance to turn round. When the room was finished and it was only two days until he was going to come, I was satisfied. Happiness is a childish thing and I am, after all, thirty-four. But naturally I was happy. I was looking forward to it.

The room was ready. There was a little boy sitting on the moon. With blond hair, a fishing rod made from bamboo with string and a float and hook at the end: a star. A drop of gold had dribbled down towards the window, as if the Heavens were melting.

My son was finally going to come.

I

She was walking home from school. It was nearly National Day. It would be the first 17 May without Mummy. Her national costume was too short. Mummy had already let the hem down twice.

Last night, Emilie had been woken by a bad dream. Daddy was fast asleep; she could hear him snoring gently through the wall as she held her national costume up against her body. The red border had crept up to her knees. She was growing too fast. Daddy often said, ‘You’re growing as fast as a weed, love.’ Emilie stroked the woollen material with her hand and tried to shrink at the knees and neck. Gran was in the habit of saying, ‘It’s not surprising the child is shooting up, Grete was always a beanpole.’

Emilie’s shoulders and thighs ached from being hunched the whole time. It was Mummy’s fault she was so tall. The red hem wouldn’t reach further than her knees.

Maybe she could ask for a new dress.

Her schoolbag was heavy. She’d picked a bunch of coltsfoot. It was so big that Daddy would have to find a vase. The stalks were long too, not like when she was little and only picked the flowers, which then had to bob about in an eggcup.

She didn’t like walking alone. But Marte and Silje had been collected by Marte’s mum. They didn’t say where they were going. They just waved at her through the rear window of the car.

The flowers needed water. Some had already started to wilt over her fingers. Emilie tried not to clutch the bunch too hard. A flower fell to the ground and she bent down to pick it up.

‘Are you called Emilie?’

The man smiled. Emilie looked at him. There was no one else to be seen here on the small path between two busy roads, a track that cut ten minutes off the walk home. She mumbled incoherently and backed away.

‘Emilie Selbu? That’s your name, isn’t it?’

Never talk to strangers. Never go with anyone you don’t know. Be polite to grown-ups.

‘Yes,’ she whispered, and tried to slip past.

Her shoe, her new trainer with the pink strips, sank into the mud and dead leaves. Emilie nearly lost her balance. The man caught her by the arm. Then he put something over her face.

An hour and a half later, Emilie Selbu was reported missing to the police.

II

‘I’ve never managed to let go of this case. Perhaps it’s my bad conscience. But then again, I was a newly qualified lawyer at a time when young mothers were expected to stay at home. There wasn’t much I could do or say.’

Her smile gave the impression that she wanted to be left alone. They’d been talking for nearly two hours. The woman in the bed gasped for breath and was obviously bothered by the strong sunlight. Her fingers clutched at the duvet cover.

‘I’m only seventy,’ she wheezed. ‘But I feel like an old woman. Please forgive me.’

Johanne Vik stood up and closed the curtains. She hesitated, not turning round.

‘Better?’ she asked after a while.

The old woman closed her eyes.

‘I wrote everything down,’ she said. ‘Three years ago. When I retired and thought I would have . . .’

She fluttered a thin hand.

‘. . . plenty of time.’

Johanne Vik stared at the folder lying on the bedside table beside a pile of books. The old woman nodded weakly.

‘Take it. There’s not much I can do now. I don’t even know if the man is still alive. If he is, he’d be . . . sixty-five. Or something like that.’

She closed her eyes again. Her head slipped slowly to one side. Her mouth opened a fraction and as Johanne bent down to pick up the red folder, she caught the smell of sick breath. She put the papers in her bag quietly and tiptoed towards the door.

‘One last thing.’

She jumped and turned back towards the old woman.

‘People ask how I can be so sure. Some think it’s just an idée fixe of an old woman who’s of no use to anyone any more. I’ve done nothing about it for so many years . . . When you’ve read through it all, I would be grateful to know . . .’

She coughed weakly. Her eyes slid shut. There was silence.

‘Know what?’

Johanne whispered, not sure if the old lady had fallen asleep. ‘I know he was innocent. It would be good to know whether you agree.’

‘But that’s not what I’m . . .’

The old woman slapped the edge of the bed lightly with her hand.

‘I know what you do. You are not interested in whether he was guilty or innocent. But I am. In this particular case, I am. And I hope you will be too. When you have read everything. Promise me that? That you’ll come back?’

Johanne smiled lightly. It was actually nothing more than a non-committal grimace.

III

Emilie had gone missing before. Never for long, though once – it must have been just after Grete died – he hadn’t found her for three hours. He looked everywhere. First he’d made some irritated phone calls, to friends, to Grete’s sister who only lived ten minutes away and was Emilie’s favourite aunt, to her grandparents who hadn’t seen the child for days. He punched in new numbers as concern turned to fear; his fingers hit the wrong keys. Then he rushed around the neighbourhood, in ever increasing circles, his fear growing into panic and he started to cry.

She was sitting in a tree writing a letter to Mummy, a letter with pictures that she was going to send to Heaven as a paper plane. He plucked her carefully from the branch and sent the plane flying in an arc over a steep slope. It glided from side to side and then disappeared over the top of two birch trees that thereafter were known as the Road to Paradise. He did not let her out of his sight for two weeks. Not until the end of the holidays when school forced him to let her go.

It was different this time.

He had never phoned the police before; her shorter and longer disappearing acts were no more than was to be expected. This was different. Panic hit him suddenly, like a wave. He didn’t know why, but when Emilie failed to come home when she should, he ran towards the school, not even noticing that he lost a slipper halfway. Her schoolbag and a big bunch of coltsfoot were lying on the path between the two main roads, a short cut that she never dared take on her own.

Grete had bought the bag for Emilie a month before she died. Emilie would never just leave it like that. Her father picked it up reluctantly. He could be wrong, it could be someone else’s schoolbag, a more careless child, perhaps. The schoolbag was almost identical, but he couldn’t be sure until he opened it, holding his breath, and saw the initials. ES. Big square letters in Emilie’s writing. It was Emilie’s schoolbag and she would never have just left it like that.

IV

The man referred to in Alvhild Sofienberg’s papers was called Aksel Seier and he was born in 1935. When he was fifteen years old, he’d started an apprenticeship as a carpenter. The papers said very little about Aksel’s childhood, except that he moved to Oslo from Trondheim when he was ten. His father got a job at the Aker shipyard after the war. The boy had three offences on his criminal record before he even reached adulthood. But nothing particularly serious.

‘Not compared with today, at least,’ Johanne mumbled to herself and read on. The paper was dry and yellow with age. The court transcripts mentioned two kiosk break-ins and an old Ford that was stolen and then left stranded on Mosseveien when it ran out of petrol. When Aksel was twenty-one, he was arrested for rape and murder.

The girl was called Hedvig and was only eight years old when she died. A customs officer found her, naked and mutilated, in a sack by a warehouse on Oslo docks. After two weeks’ intense investigation, Aksel Seier was arrested. It was true that there was no technical evidence. No traces of blood, no fingerprints. No footprints or marks of any kind to link the person to the crime. But he had been seen there by two reliable witnesses, out on honest business late that night.

At first the young man denied it vigorously. But eventually he admitted that he had been in the area between Pipervika and Vippetangen on the night that Hedvig was killed. Just doing some bootlegging, but he refused to give the customer’s name.

Only a few hours after his arrest, the police had managed to dig up an old charge for flashing. Aksel was only eighteen when the incident took place, and according to his own statement he was simply urinating when drunk at Ingierstrand one summer evening. Three girls had passed him. He just wanted to tease them, he said. Drunken horseplay and high spirits. He wasn’t like that. He hadn’t flashed at them, but was just joking around with three hysterical girls.

The charge was later dropped, but never quite disappeared. Now it was resurrected from oblivion like an indignant finger pointing at him, a stigma that he thought had been forgotten.

When his name was published in the newspapers, in big headlines that led Aksel’s mother to commit suicide on the night before Christmas 1956, three more incidents were reported to the police. One was discreetly dropped when the prosecuting authorities discovered that the middle-aged woman in question was in the habit of reporting a rape every six months. The other two were used for all they were worth.

Margrete Solli had dated Aksel for three months. She had strong principles. Which didn’t suit Aksel, she claimed, blushing with downcast eyes. On more than one occasion he had forced her to do what should only be done in marriage.

Aksel himself told another version. He recalled delightful nights by Sognsvann, when she giggled and said no and slapped his hands playfully as they crept over her naked skin. He remembered passionate goodbye kisses and his own half-baked promises of marriage when he had finished his apprenticeship. He told the police and the judge that he’d had to persuade the young girl, but no more than was normal. That’s just the way women are before they get a ring on their finger, is it not?

The third charge was made by a woman that Aksel Seier claimed he had never met. The alleged rape had taken place many years before when the girl was only fourteen. Aksel denied it repeatedly. He had never seen her before in his life. He stubbornly stuck to this throughout his nine-week custody and the long and devastating trial. He had never seen the woman. He had never even heard of her.

But then he was known to be a liar.

When he was charged with murder, Aksel finally gave the name of the customer who could give him an alibi. The man was called Arne Frigaard and had bought twenty bottles of good moonshine for twenty-five kroner. When the police went to check this story, they met an astonished Colonel Frigaard at his home in Frogner. He rolled his eyes when he heard the gross accusations and showed the two constables his bar. Honest drinks, every one. His wife said very little, it was noted, but nodded when her pompous husband insisted that he had been at home nursing a migraine on the night in question. He had gone to bed early.

Johanne stroked her nose and took a sip of cold tea.

There was nothing to indicate that anyone had investigated the Colonel’s story any further. All the same, she could sense the irony, or perhaps even sarcastic objectivity, in the judge’s dry, factual rendition of the policeman’s testimony. The Colonel himself had not been called as a witness in court. He suffered from migraines, his doctor claimed, thereby sparing his patient of many years the embarrassment of being confronted with allegations of buying cheap spirits.

Johanne jumped when she heard noises from the bedroom. Even after all this time, even when things had been so much better for the past five years – the child was healthy now, and usually slept soundly from sunset to sunrise and probably just had a bit of a cold – she felt a chill run down her spine whenever she heard the slightest sleepy cough. All was quiet again.

One witness in particular stood out. Evander Jakobsen was seventeen years old and was in prison himself. However, he had been free when little Hedvig was murdered and claimed that he’d been paid by Aksel Seier to carry a sack for him from an address in the old part of town, down to the harbour. In his first statements, he said that Seier walked through the night streets with him, but didn’t want to carry the sack himself as ‘that would draw too much attention’. He later changed his story. It was not Seier who had asked him to carry the sack, but another – unidentified – man. In the new version, Seier met him at the harbour and took the sack from him without saying much. The sack supposedly contained old pigs’ heads and trotters. Evander Jakobsen couldn’t be certain, as he never checked. But it stank, that’s for sure, and it could have weighed roughly the same as an eight-year-old

This obviously phoney story had sowed seeds of doubt in the mind of Dagbladet’s crime reporter. He described Evander Jakobsen’s explanation as ‘highly implausible’ and had found support for this in Morgenbladet, where the reporter unashamedly mocked the young jailbird’s conflicting stories from the witness stand.

But the journalists’ doubts and reservations were of little help.

Aksel Seier was sentenced for the rape of little Hedvig Gåsøy, aged eight. He was also found guilty of killing her with the intent to destroy any evidence of the first crime.

He was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Johanne placed all the papers carefully one on top of the other. The small pile contained transcripts of the judgment and a large number of newspaper articles. No police documents. No records of questioning. No expert reports, though it was clear that several of these had existed.

The newspapers stopped writing about the case soon after the verdict was given.

For Johanne, Aksel Seier’s sentence was just one of many similar cases. It was the end of the story, however, that made it different and that made it hard to sleep. It was half past twelve and she wasn’t in the slightest bit sleepy.

She read through the papers again. Under the verdicts, attached to the newspaper cuttings with a paper clip, was the old lady’s alarming account.

Eventually Johanne stood up. It was starting to get light outside. She would have to be up in a few hours. When she nudged the child over to the other side of the bed, the little girl grunted sleepily. She could just stay where she was. Sleep was a long way off anyway.

V

‘It’s an unbelievable story.’

‘Do you mean that literally? That you actually don’t believe me?’

The room had just been aired. The sick woman was more alert. She was sitting up in bed and the TV in the corner was on, without any sound. Johanne smiled and brushed her fingers lightly over the bedspread that was hanging on the arm of the chair.

‘Of course I believe you. Why shouldn’t I?’

Alvhild Sofienberg didn’t answer. Her eyes moved from the younger woman to the silent television. Pictures flickered ceaselessly and without meaning on the screen. The old lady had blue eyes. Her face was oval-shaped and it was as if her lips had been wiped out by the intense pain that came and went. Her hair had withered away to thin wisps that lay close to the narrow skull.

Maybe she had been beautiful once. It was difficult to say. Johanne studied her ravaged features and tried to imagine what she must have looked like in 1965. Alvhild Sofienberg had turned thirty-five that year.

‘I was born in 1965,’ Johanne said suddenly, putting down the folder. ‘On 22 November, exactly two years after Kennedy was assassinated.’

‘My children were already quite old. I had just taken my law exams.’

The old lady smiled, a real smile; her grey teeth shone in the taut opening between her nose and throat. Her consonants were harsh, and her vowels muted. She reached out for a glass and took a drink of water.

Alvhild Sofienberg’s first job was as an executive officer for the Norwegian Correctional Services. She was responsible for preparing applications for royal pardons. Johanne already knew that. She had read it in the papers, in the old lady’s story that was stapled to the judgment and some yellowing newspaper clippings about a man called Aksel Seier who was sentenced for the murder of a child.

‘A boring job, actually. Particularly when I look back on it now. I don’t recall being unhappy. Quite the opposite. I had training, a qualification, a . . . I had a university degree, which was very impressive. At the time. In my family, at least.’

She revealed her teeth again, and tried to moisten her tight mouth with the tip of her tongue.

‘How did you get hold of all the documents?’ asked Johanne, and refilled the glass with water from the carafe.

The ice cubes had melted and the water was tinged with the smell of onions.

‘I mean, it’s never really been the case that applications for pardons are accompanied by all the case documentation. Police interrogations and the like. I don’t quite see how you can . . .’

Alvhild tried to straighten her back. When Johanne leaned over to help her, she again registered the smell of old onions. It intensified, the smell became a stench that filled her nostrils and made her gag. She disguised the cramps in her diaphragm by coughing.

‘I smell of onions,’ the old lady said sharply. ‘No one knows why.’

‘Maybe it’s . . .’

Johanne waved her finger in the direction of the water carafe.

‘Other way round,’ coughed the old lady. ‘The water gets its smell from me. You’ll just have to put up with it. I asked for them.’

She pointed at the folder that had fallen on the floor.

‘As I wrote there, I can’t quite explain what it was that roused my interest. Maybe it was the simplicity of the application. The man had been in prison for eight years and had never pleaded guilty. He had applied for a pardon three times before and been rejected every time. But he still didn’t complain. He didn’t claim to be ill, as most people did. He hadn’t written page upon page about his deteriorating health, his family and children who were missing him at home and the like. His application was only one line. Two sentences. “I am innocent. Therefore I request a pardon.” It fascinated me. So I asked for all the papers. The pile of documents . . .’

Alvhild tried to lift her hands.

‘Was nearly a metre high. I read and read and was more and more convinced.’

Her fingers trembled with the strain and she lowered her arms.

Johanne bent down to pick up the folder from the floor. She had goosebumps on her arms. The window was slightly open and there was a draught coming through. The curtains moved unexpectedly and she jumped. Blue headlines flickered on the TV screen, and it suddenly annoyed her that the television was on for no reason.

‘Do you agree? He was innocent? He was not proven guilty. And someone has tried to cover it up.’

Alvhild Sofienberg’s voice had taken on a sharp undertone, an aggressive edge. Johanne leafed through the brittle papers without saying anything.

‘Well, it’s pretty obvious,’ she said, barely audibly.

‘What did you say?’

‘Yes, I agree with you.’

It was as if the patient was suddenly drained of all her energy. She sank back into the pillow and closed her eyes. Her face became more peaceful as if the pain was no longer there. Only her nostrils quivered slightly.

‘Perhaps the most frightening thing is not that he wasn’t proven guilty,’ said Johanne slowly. ‘The worst thing is that he never . . . what happened afterwards, after he was released, that he even . . . I’d be surprised if he was still alive.’

‘Another one,’ said Alvhild wearily, looking at the television; she turned up the volume on the remote control that was attached to the bedframe. ‘Another child has been kidnapped.’

A little boy smiled bashfully from an amateur photograph. He had brown curly hair and was clutching a red plastic fire engine to his chest. Behind him, out of focus, you could make out an adult laughing.

‘The mother, perhaps. Poor thing. Wonder if it’s connected. To the girl, I mean. The one who . . .’

Kim Sande Oksøy had disappeared from his home in Bærum last night, said the metallic voice. The TV set was old, the picture too blue and the sound tinny. The abductor had broken into the terraced house while the family was asleep; a camera panned over a residential area and then focused on a window on the ground floor. The curtains were billowing gently and the camera zoomed in on a broken sill and a green teddy bear on the shelf just inside. The policeman, a young man with hesitant eyes and an uncomfortable uniform, appealed to anyone who might have information to call in on the 800 number, or to contact their nearest police station.

The boy was only five years old. It was now six days since nine-year-old Emilie Selbu had disappeared on her way home from school.

Alvhild Sofienberg had fallen asleep. There was a small scar near her narrow mouth, a cleft from the corner of her mouth up towards her ear. It made her look as if she was smiling. Johanne crept out of the room, and as she went down to the ground floor a nurse came towards her. She said nothing, just stopped on the stairs and stepped to one side. The nurse also smelt of onions, a vague scent of onion and detergent. Johanne felt sick. She pushed past the other woman, not knowing whether she would return to this house where an old dying lady upstairs made the smell of decay cling to everything and everyone.

VI

Emilie felt bigger when the new boy arrived. He was even more frightened than she was. When the man pushed him into the room a while ago, he had pooed his pants. Even though he was nearly old enough to be at school. At one end of the room there was a sink and a toilet. The man had thrown a towel and a bar of soap in with the boy and Emilie managed to tidy him up. But there were no clean clothes anywhere. She pushed the dirty pants in under the sink, between the wall and the pipe. The boy just had to go without pants and would not stop crying.

Until now. He had finally fallen asleep. There was only one bed in the room. It was very narrow and probably very old. The woodwork was brown and worn and someone had drawn on it with a felt-tip that was barely visible any more. When Emilie lifted the sheet she saw that the mattress was full of long hair; a woman’s hair was stuck to the foam mattress and she quickly tucked the sheet back in place. The boy lay under the duvet with his head in her lap. He had brown curly hair and Emilie started to wonder if he could talk at all. He had snivelled his name when she asked. Kim or Tim. It was hard to make out. He had called for his mother, so he wasn’t entirely mute.

‘Is he sleeping?’

Emilie jumped. The door was ajar. The shadows made it hard to see his face, but his voice was clear. She nodded weakly.

‘Is he sleeping?’

The man didn’t seem to be angry or annoyed. He didn’t bark like Daddy sometimes did when he had to ask the same question several times.

‘Yes.’

‘Good. Are you hungry?’

The door was made of iron. And there was no handle on the inside. Emilie did not know how long she had been in the room with the toilet and the sink in one corner and the bed in the other and nothing else apart from plaster walls and the shiny door. It was a long time, that was all she knew. She had tried the door a hundred times at least. It was smooth and ice cold. The man was scared that it would shut behind him. The few times that he had come into the room, he had fixed the door to a hook on the wall. Normally when he brought her food and something to drink, he left it on a tray just inside the door.

‘No.’

‘OK. You should go to sleep as well. It’s night.’

Night.

The sound of the heavy iron door closing made her cry. Even though the man said it was night, it didn’t feel like it. There was no window in the room and the light was left on the whole time, so there was no way of knowing whether it was day or night. At first she had thought that slices of bread and milk meant that it was breakfast and the stews and pancakes that the man left on the tray were supper. She finally understood, but then the man started to play tricks. Sometimes she got bread three times in a row. Today, after Kim or Tim had stumbled into her world, the man had given them tomato soup twice. It was lukewarm and there was no macaroni in it.

Emilie tried to stop crying. She didn’t want to wake the boy. She held her breath so that she wouldn’t shake, but it didn’t work.

‘Mummy,’ she sobbed, without wanting to. ‘I want my mummy.’

Daddy would be looking for her. He must have been looking for a long time. Daddy and Auntie Beate were no doubt still running around in the woods, even though it was night. Maybe Granddad was there too. Gran had sore feet, so she would be at home reading books or making waffles for the others to eat when they’d been to the Road to Paradise and the Heaven Tree and not found her anywhere.

‘Mummy,’ whimpered Kim or Tim and then howled.

‘Hush.’

‘Mummy! Daddy!’

The boy got up suddenly and shrieked. His mouth was a great gaping hole. His face twisted into one enormous scream and she pressed herself against the wall and closed her eyes.

‘You mustn’t scream,’ she said in a flat voice. ‘The man will get angry with us.’

‘Mummy! I want my daddy!’

The boy caught his breath. He was gasping for air, and when Emilie opened her eyes she saw that his face was dark red. Snot was running from one nostril. She grabbed one corner of the duvet and wiped him clean. He tried to hit her.

‘Don’t want,’ he said and sobbed again. ‘Don’t want.’

‘Shall I tell you a story?’ asked Emilie.

‘Don’t want.’

He pulled his sleeve across his nose.

‘My mummy is dead,’ said Emilie and smiled a bit. ‘She’s sitting in Heaven watching over me. Always. I’m sure she can watch over you too.’

‘Don’t want.’

At least the boy was not crying so hard any more.

‘My mummy is called Grete. And she’s got a BMW.’

‘Audi,’ said the boy.

‘Mummy’s got a BMW in Heaven.’

‘Audi,’ the boy repeated, with a cautious smile that made him much nicer.

‘And a unicorn. A white horse with a horn in its forehead that can fly. Mummy can fly anywhere on her unicorn when she can’t be bothered to use the BMW. Maybe she’ll come here. Soon, I think.’

‘With a bang,’ said the boy.

Emilie knew very well that her mother didn’t have a BMW. She wasn’t in Heaven at all and unicorns don’t exist. There was no Heaven either, even though Daddy said there was. He liked so much to talk about what Mummy was doing up there, everything that she had always wanted, but they could never afford. In Paradise, nothing cost anything. They didn’t even have money there, Daddy said, and smiled. Mummy could have whatever she wanted and Daddy thought it was good for Emilie to talk about it. She had believed him for a long time and it was good to think that Mummy had diamonds as big as plums in her ears as she flew around in a red dress on a unicorn.

Auntie Beate had told Daddy off. Emilie disappeared to write a letter to Mummy and when Daddy eventually found her, Auntie Beate shouted so loudly that the walls shook. The grown-ups thought Emilie was asleep. It was late at night.

‘It’s about time you told the child the truth, Tønnes. Grete is dead. Full stop. She is ashes in an urn and Emilie is old enough to understand. You have to stop. You’ll ruin her with all your stories. You’re keeping Grete alive artificially and I’m not even sure who you’re actually trying to fool, yourself or Emilie. Grete is dead. DEAD, do you understand?’

Auntie Beate was crying and angry at the same time. She was the cleverest person in all the world. Everyone said that. She was a senior doctor and knew everything about sick hearts. She saved people from certain death, just because she knew so much. If Auntie Beate said that Daddy’s stories were rubbish, then she must be right. A few days later, Daddy had taken Emilie out into the garden to look at the stars. There were four new holes in the sky, because Mummy wanted to see her better, he told her, pointing. Emilie didn’t answer. He was sad. She could see it in his eyes when he picked up a book and started to read to her on the bed. She refused to listen to the rest of the story about Mummy’s trip to Japan Heaven, a story that had stretched over three evenings and was actually quite funny. Daddy made money from translating books and was a bit too fond of stories.

‘I’m called Kim,’ said the boy, and put his thumb in his mouth.

‘I’m called Emilie,’ said Emilie.

They didn’t know that it was starting to get light when they fell asleep.

One and half storeys above them, at ground level, in a house on the edge of a small wood, a man sat and stared out of the window. He was feeling remarkably good, nearly intoxicated, as if he was facing a challenge that he knew he could master. It was impossible to sleep properly. During the night he had sometimes felt himself slipping away, only to be roused again by a very clear thought.

The window looked west. He saw the darkness huddle in behind the horizon. The hills on the other side of the valley were bathed in strips of morning light. He got up and put the book on the table.

No one else knew. In less than two days one of the two children in the cellar would be dead. He felt no joy in this knowledge, but a feeling of elated determination made him indulge in a bit of sugar and a drop of milk in the bitter coffee from the night before.

VII

‘Welcome to the programme, Johanne Vik. Now, you are a lawyer and a psychologist, and you wrote your thesis on why people commit sexually motivated crimes. Given recent events . . .’

Johanne closed her eyes for a moment. The lights were strong. But it was still cold in the enormous room and she felt the skin on her forearms contract.

She should have refused the invitation. She should have said no. Instead she said:

‘Let me first clarify that I did not write a thesis on why some people commit sex crimes. As far as I know, no one knows that for certain. I did, however, compare a random selection of convicted sex offenders with an equally random selection of other offenders to look at the similarities and differences in background, childhood and early adult years. My thesis is called, Sexually Motivated Crime, a comp . . .’

‘Oh, that’s a bit complicated, Ms Vik. So to put it simply, you wrote a thesis about sex offenders. Two children have been brutally snatched from their parents in less than a week. Do you think there can be any doubt that these are sexually motivated crimes?’

‘Doubt?’

She didn’t dare to pick up the plastic cup of water. She clasped her fingers together to stop her hands from shaking uncontrollably. She wanted to answer. But her voice let her down. She swallowed.

‘Doubt has got nothing to do with it. I don’t see how there can be any basis for making such a claim.’

The presenter lifted his hand and frowned in irritation, as if she had broken some kind of deal.

‘Of course it is possible,’ she corrected herself. ‘Everything is possible. Children can be molested, but in this case it might equally be something different. I am not a detective and only know about the case from the media. All the same, I would assume that the investigation has not yet even concluded that the two . . . abductions, I guess that is what we should call them . . . are in any way connected. I agreed to come on the show on the understanding that . . .’

She had to swallow again. Her throat was tight. Her right hand was shaking so much that she had to surreptitiously push it under her thigh. She should have said no.

‘And you,’ the presenter said cockily to a lady in a black jacket, with long silver hair. ‘Solveig Grimsrud, director for the newly established Protect Our Children, you are clearly of the opinion that this is a case of paedophilia?’

‘Given what we know about similar cases abroad, it would be incredibly naïve to think anything else. It is difficult to imagine any alternative motives for abducting children – children that have absolutely nothing to do with each other, if we are to believe the papers. We know of cases in the US, Switzerland, not to mention those gruesome cases in Belgium only a few years ago . . . We all know these cases and we all know what the outcome was.’

Grimsrud patted her heart. There was a loud scraping noise in the microphone that was attached to her lapel. Johanne noticed a technician holding his ears, just off camera.

‘What do you mean by . . . outcome?’

‘I mean what I say. Children are always abducted for one of three reasons.’

Her long hair was falling into her eyes and Solveig Grimsrud pushed it behind her ears before counting on her fingers.

‘Either it is simply a case of extortion, which we can ignore in these cases. Both families have average incomes and are not wealthy. Then there are a small number of children who are abducted by either their mother or their father, generally the latter, when a relationship breaks down. And again, that is not the case here. The girl’s mother is dead and the boy’s parents are still married. Which leaves the last alternative. The children have been abducted by one or more paedophiles.’

The presenter hesitated.

Johanne thought about waking up and feeling a naked child’s stomach against her back, the tickle of sleepy fingers against her neck.

A man in his late fifties with aviator specs and downcast eyes took a deep breath and started to talk.

‘In my opinion, Grimsrud’s theory is just one of many. I think we should be . . .’

‘Fredrik Skolten,’ interrupted the presenter. ‘You are a private detective, with twenty years’ experience in the police force. And just to let our viewers know, NCIS Norway, the National Criminal Investigation Service, was invited to come on the show this evening, but declined. But, Skolten, given your extensive experience in the police, what theories do you think they are working on?’

‘As I was just saying . . .’

The man studied a spot on the table and rubbed his right index finger in a regular movement against the back of his left hand.

‘At the moment they are probably keeping things very open. But there is a lot of truth in what Ms Grimsrud said. Child abductions do generally fall into three categories, which she . . . And the first two would appear to be reasonably . . .’

‘Unlikely?’

The presenter leaned closer, as if they were having a private conversation.

‘Well. Yes. But there is no basis for . . . Without any further . . .’

‘It’s time people woke up,’ interrupted Solveig Grimsrud. ‘Only a few years ago we thought that the sexual abuse of children didn’t concern us. It was something that only happened out there, in the USA, far away. We have let our children walk on their own to school, go on camping trips without adult supervision, be away from home for hours on end without making sure that they’re being supervised. It cannot continue. It’s time that we . . .’

‘It’s time that I left.’

Johanne didn’t realise that she had stood up. She stared straight into the camera, an electronic cyclops that stared back with an empty grey eye and made her freeze. Her microphone was still attached to her jacket.

‘This is ridiculous. Somewhere out there . . .’

She pointed her finger at the camera and held it there.

‘. . . is a widower whose daughter disappeared a week ago. There is a couple whose son was abducted, snatched from them in the middle of the night. And you are sitting here . . .’

She moved her hand to point at Solveig Grimsrud; it was shaking.

‘. . . telling them that the worst thing imaginable has happened. You have absolutely no grounds, and I repeat, no grounds for saying that. It is thoughtless, malicious . . . Irresponsible. As I said, I only know what I have seen in the media, but I hope . . . In fact I am certain that the police are still keeping all options open, unlike you. Off the top of my head, I can think of six or seven different explanations for the abductions, and each is as good or bad as the next. And they are at least based on stronger arguments than your speculative scenario. It’s only twenty-four hours since little Kim disappeared. Twenty-four hours! Words fail me . . .’

And she meant it literally. Suddenly she was quiet. Then she pulled the microphone from her jacket and disappeared. The camera followed her as she made for the studio door, with heavy, unfamiliar movements.

‘Well,’ said the presenter; there was sweat on his upper lip and he was breathing through his mouth. ‘That was quite something.’

*

Somewhere else in Oslo, two men were sitting watching TV. The older one smiled slightly and the younger one thumped the wall with his fist.

‘Shit, you can say that again. Do you know that woman? Have you heard of her?’

The older man, Detective Inspector Adam Stubo, from the NCIS, nodded thoughtfully.

‘I read the thesis she mentioned. Interesting, actually. She’s now looking at the media’s coverage of serious crimes. As far as I can understand from the article I read, she’s comparing the fate of a number of convicted criminals who got a lot of press attention, with those who didn’t. They all pleaded innocent. She’s gone way back, to the fifties I think. Don’t know why.’

Sigmund Berli laughed.

‘Well, she’s certainly got balls. I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone just get up and leave. Good for her. Especially as she was right!’

Adam Stubo lit a huge cigar, which signalled that he now considered the working day to be over.

‘She is so right that it might be interesting to talk to her,’ he said, grabbing his jacket. ‘See you tomorrow.’

VIII

A child doesn’t know when it’s going to die. It has no concept of death. Instinctively it fights for life, like a lizard that’s willing to give up its tail when threatened with extermination. All beings are genetically programmed to fight for survival. Children as well. But they have no concept of death. A child is frightened of real things. The dark. Strangers, perhaps, being separated from their family, pain, scary noises and the loss of objects. Death, on the other hand, is incomprehensible for a mind that is not yet mature.

A child does not know that it is going to die.

That is what the man was thinking as he got everything ready. He poured some Coke into an ordinary glass and wondered why he was bothering with such thoughts. Even though the boy had not been picked at random, there were no emotional ties between them. The boy was a total stranger, emotionally, a pawn in an important game. He wouldn’t feel anything. In that sense, he was better served by dying. He missed his parents, a pain that was both understandable and to be expected in a boy of five and surely that was worse than a swift, painless death.

The man powdered the Valium pill and sprinkled the pieces into the glass. It was a small dose, he just wanted the boy to fall asleep. It was important that he was asleep when he died. It was easiest. Practical. Injecting children is hard enough, without them shouting and kicking.

The Coke made him thirsty. He moistened his lips slowly with his tongue. A shiver ran through the muscles in his back; in a way he was looking forward to it. To completing his detailed plan.

It would take six weeks and four days, if everything went according to schedule.