Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

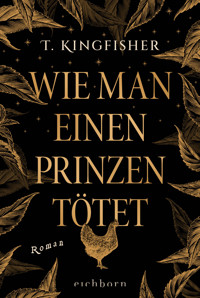

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

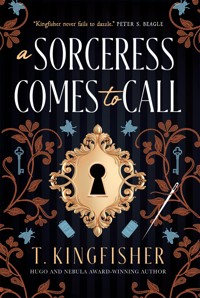

THE 2025 HUGO AND NEBULA AWARD NOMINEE FOR BEST NOVEL From New York Times bestselling and Hugo Award-winning author T. Kingfisher comes a dark retelling of the Brothers Grimm's Goose Girl, rife with secrets, murder, and forbidden magic. Perfect for fans of Naomi Novic, Alix E. Harrow and Nettle & Bone. Cordelia knows her mother is unusual. Their house doesn't have any doors between rooms—there are no secrets in this house! Cordelia isn't allowed to have a single friend. The only time she feels truly free is on her daily rides with her mother's beautiful white horse, Falada. But more than a few quirks set her mother apart. Other parents can't force their daughters to be silent and motionless—obedient—for hours or days on end. Other mothers aren't . . . sorcerers. After a suspicious death in their small town, Cordelia's mother insists they leave in the middle of the night, leaving behind all Cordelia has ever known. They arrive at the remote country manor of a wealthy older man, the Squire, and his unwed sister, Hester. Cordelia's mother intends to lure the Squire into marriage. Cordelia knows this can only be bad news for the bumbling gentleman and his kind, intelligent sister. Hester sees the way Cordelia shrinks away from her mother. How the young girl sits eerily still at dinner every night. She knows that to save her brother from bewitchment and to rescue the terrified Cordelia, she will have to face down a wicked witch of the worst kind.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 501

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by T. Kingfisher and available from Titan Books

The Twisted Ones

The Hollow Places

Nettle & Bone

A House with Good Bones

Thornhedge

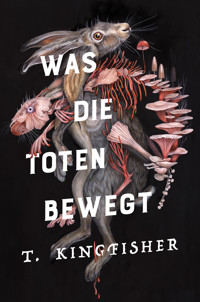

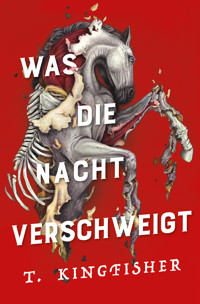

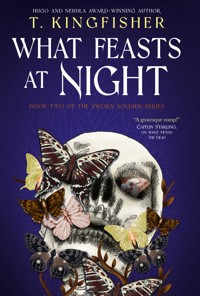

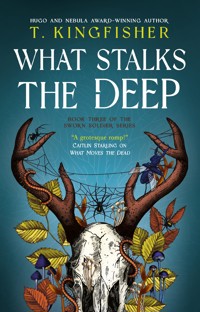

THE SWORN SOLDIER SERIES

What Moves the Dead

What Feasts at Night

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

A Sorceress Comes to Call

Hardback edition ISBN: 9781789098297

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789098303

Export edition ISBN: 9781835411513

Broken Binding edition ISBN: 9781835412282

Dryad edition ISBN: 9781835412299

Forbidden Planet edition ISBN: 9781835412411

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: August 2024

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© T. Kingfisher 2024.

T. Kingfisher asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

To Deb

1

There was a fly walking on Cordelia’s hand and she was not allowed to flick it away.

She had grown used to the ache of sitting on a hard wooden pew and being unable to shift her weight. It still hurt, but eventually her legs went to sleep and the ache became a dull, all-over redness that was easier to ignore.

Though her senses were dulled in obedience, her sense of touch stayed the strongest. Even when she was so far under that the world had a gray film around the edges, she could still feel her clothing and the touch of her mother’s hand. And now the fly’s feet itched, which was bad, then tickled, which was worse.

At the front of the church, the preacher was droning on. Cordelia had long since lost the thread. Lust and tithing were his two favorite topics. Probably it was one of those. Her mother took her to church every Sunday and Cordelia was fairly certain that he had been preaching the same half-dozen sermons for the past year.

Her eyes were the only muscles that she could control, so she was not looking at him, but down as far as she could. At the very bottom of her vision, she could see her hands folded in her lap and the fly picking its way delicately across her knuckles.

Her mother glanced at her and must have noticed that she was looking down. Cordelia’s chin rose so that she could no longer see her hands. She was forced to study the back of the head of the man in front of her. His hair was thinning toward the back and was compressed down at the sides, as if he wore a hat most days. She did not recognize him, but that was no surprise. Since her days at school had ended, Cordelia only saw the other townsfolk when she went to church.

Cordelia lost the tickling sensation for a moment and dared to hope that the fly was gone, but then the delicate web between her thumb and forefinger began to itch.

Her eyes began to water at the sensation and she blinked them furiously. Crying was not acceptable. That had been one of the first lessons of being made obedient. It would definitely not be acceptable in church, where other people would notice. Cordelia was fourteen and too old to cry for seemingly no reason—because of course she could not tell anyone the reason.

The fly crossed over to her other hand, each foot landing like an infinitesimal pinprick. The stinging, watering sensation in her eyes started to feel like a sneeze coming on.

Sneezing would be terrible. She could not lift her hands or turn her head, so it would hit the back of the man’s head, and he would turn around in astonishment and her mother would move her mouth to apologize and everyone would be staring at her for having been so ill-mannered.

Her mother would not be happy. Cordelia would have given a year of her life to be able to wipe her eyes. She sniffed miserably, her lungs filling with the smell of candles and wood polish and other people’s bodies. Under it all lay the dry, sharp smell of wormwood.

And then, blessedly, the preacher finished. Everyone said, “Amen,” and the congregation rose. No one noticed that Cordelia moved in unison with her mother.

No one ever did.

* * *

“I suppose you’re mad at me,” said her mother as they walked home from church. “I’m sorry. But you might try harder not to be so rebellious! I shouldn’t have to keep doing this to you, not when you’re fourteen years old!”

Cordelia said nothing. Her tongue did not belong to her. The person that smiled and answered all the greetings after the sermon—“Why Evangeline, don’t you look lovely today? And Cordelia! You keep growing like a weed!”—had not been Cordelia at all.

They reached home at last. Home was a narrow white house with peeling paint, set just off the road. Evangeline pushed the front door open, walked Cordelia to the couch, and made her sit.

Cordelia felt the obedience let go, all at once. She did not scream.

When Cordelia was young, she had screamed when she came out of obedience, but this gave her mother a reason to hold her and make soothing noises, so she had learned to stay silent as she swam up into consciousness, out of the waking dream.

The memories of what she had done when she was obedient would still be there, though. They lay in the bottom of her skull like stones.

It was never anything that looked terrible from outside. She could not have explained it to anyone without sounding ridiculous. “She makes me eat. She makes me drink. She makes me go to the bathroom and get undressed and go to bed.”

And they would have looked at her and said “So?” and Cordelia would not have been able to explain what it was like, half-sunk in stupor, with her body moving around her.

Being made obedient felt like being a corpse. “My body’s dead and it doesn’t do what I want,” Cordelia had whispered once, to her only friend, their horse Falada. “It only does what she wants. But I’m still in it.”

When she was younger, Cordelia would wet herself frequently when she was obedient. Her mother mostly remembered to have Cordelia relieve herself at regular intervals now, but Cordelia had never forgotten the sensation.

She was made obedient less often as she grew older. She thought perhaps that it was more difficult for her mother to do than it had been when she was small—or perhaps it was only that she had learned to avoid the things that made her mother angry. But this time, Cordelia hadn’t avoided it.

As the obedience let go, Cordelia swam up out of the twilight, feeling her senses slot themselves back into place.

Her mother patted her shoulder. “There you are. Now, isn’t that better?”

Cordelia nodded, not looking at her.

“I’m sure you’ll do better next time.”

“Yes,” said Cordelia, who could not remember what it was that she had been made obedient for. “I will.”

When her legs felt steady enough, she went up the stairs to her bedroom and lay on the bed. She did not close the door.

* * *

There were no closed doors in the house she grew up in.

Sometimes, when her mother was gone on an errand, Cordelia would close the door to her bedroom and lean against it, pressing herself flat against the wooden surface, feeling it solid and smooth under her cheek.

The knowledge that she was alone and no one could see her—that she could do anything, say anything, think anything and no one would be the wiser—made her feel fierce and wicked and brave.

She always opened the door again after a minute. Her mother would come home soon and the sight of a closed door would draw her like a lodestone. And then there would be the talk.

If Cordelia’s mother was in a good mood, it would be “Silly! You don’t have any secrets from me, I’m your mother!”

If she was in a bad mood, it would be the same talk but from the other direction, like a tarot card reversed—“What are you trying to hide?”

Whichever card it was, it always ended the same way: “We don’t close doors in this house.”

When Cordelia was thirteen and had been half-mad with things happening under her skin, she shot back “Then why are there doors in the house at all?”

Her mother had paused, just for an instant. Her long-jawed face had gone blank and she had looked at Cordelia—really looked, as if she was actually seeing her—and Cordelia knew that she had crossed a line and would pay for it.

“They came with the house,” said her mother. “Silly!” She nodded once or twice, to herself, and then walked away.

Cordelia couldn’t remember now how long she had been made obedient as punishment. Two or three days, at least.

Because there were no closed doors, Cordelia had learned to have no secrets that could be found. She did not write her thoughts in her daybook.

She kept a daybook because her mother believed that it was something young girls should do, but the things she wrote were exactly correct and completely meaningless. I spilled something on my yellow dress today. I have been out riding Falada. The daffodils bloomed today. It is my birthday today.

She gazed at the pages sometimes, and thought what it would be like to write I hate my mother in a fierce scrawl across the pages.

She did not do it. Closing the door when she was home alone was as much rebellion as she dared. If she had written something so terrible, she would have been made obedient for weeks, perhaps a month. She did not think she could stand it for so long.

I’d go mad. Really truly mad. But she wouldn’t notice until she let me come back, and I’d have been mad inside for weeks and weeks by then.

Since her mother was home today and unlikely to leave again, Cordelia took a deep breath and sat up, scrubbing at her face. There was no point in dwelling on things she would never do. She changed out of her good dress and went out to the stable behind the house, where Falada was waiting. The stable was old and gloomy, but Falada glowed like moonlight in the darkness of his stall.

When Falada ran, and Cordelia clung to his back, she was safe. It was the only time that she was not thinking, not carefully cropping each thought to be pleasant and polite and unexceptional. There was only sky and hoofbeats and fast-moving earth.

After a mile or so, the horse slowed to a stop, almost as if he sensed what Cordelia needed. She slipped off his back and leaned against him. Falada was quiet, but he was solid and she told him her thoughts, as she always did.

“Sometimes I dream about running,” she whispered. “You and me. Until we reach the sea.”

She did not know what she would do once they reached the sea. Swim it, perhaps. There was another country over there, the old homeland that adults referred to so casually.

“I know I’m being ridiculous,” she told him. “Horses can’t swim that far. Not even you.”

She had learned not to cry long ago, but she pressed her face to his warm shoulder, and the wash of his mane across her skin felt like tears.

Cordelia was desperately thankful for Falada, and that her mother encouraged her to ride, although of course Evangeline’s motives were different from Cordelia’s. “You won’t get into any trouble with him,” her mother would say. “And besides, it’s good for a girl to know how to ride. You’ll marry a wealthy man someday, and they like girls who know their way around a horse, not these little town girls that can only ride in a carriage!” Cordelia had nodded. She did not doubt that she would marry a wealthy man one day. Her mother had always stated it as fact.

And, it was true that the girls Cordelia saw when riding seemed to envy her for having Falada to ride. He was the color of snow, with a proud neck. She met them sometimes in the road. The cruel ones made barbed comments about her clothes to hide their envy, and the kind ones gazed at Falada wistfully. That was how Cordelia met Ellen.

“He’s very beautiful,” Ellen had said one day. “I’ve never seen a horse like him.”

“Thank you,” said Cordelia. She still went to school then, and talking to other people had not seemed quite so difficult. “He is a good horse.”

“I live just over the hill,” the other girl had said shyly. “You could visit sometime, if you like.”

“I would like that,” Cordelia had replied carefully. And that was true. She would have liked that.

But Cordelia did not go, because her mother would not have liked that. She did not ask. It was hard to tell, sometimes, what would make her mother angry, and it was not worth the risk. Still, for the last three years she had encountered the kind girl regularly. Ellen was the daughter of a wealthy landowner that lived nearby. She rode her pony, Penny, every day, and when she and Cordelia met, they rode together down the road, the pony taking two steps for every one of Falada’s.

So it was unsurprising when Cordelia heard the familiar hoofbeats of Ellen’s pony approaching. She lifted her head from Falada’s neck and looked up as Ellen waved a hello. Cordelia waved back and remounted. Penny shied at their approach, but Ellen reined her in.

Cordelia had never ridden any horse but Falada, so it was from Ellen—and from watching Ellen’s pony—that she learned that most horses were not so calm as Falada, nor so safe. When she was very young and the open doors in their house became too much, when she couldn’t stand being in that house for one more second, she would creep to Falada’s stall and sleep curled up there, with his four white legs like pillars around her. Apparently most people did not do this, for fear the horse would step on them. Cordelia had not known to be afraid of such a thing.

“Oh, Penny! What’s gotten into you? It’s just Falada.” Ellen rolled her eyes at Cordelia, as if they shared a joke, which was one of the reasons that Cordelia liked her.

“Penny’s a good pony,” Cordelia said. She liked it when Ellen complimented Falada, so perhaps Ellen would like it when she complimented Penny. Cordelia talked to other people so rarely now that she always had to feel her way through these conversations, and she was not always good at them.

“She is,” said Ellen happily. “She’s not brave, but she’s sweet.”

Ellen carried the conversation mostly by herself, talking freely about her home, her family, the servants, and the other people in town. There was no malice in it, so far as Cordelia could tell. She let it wash over her, and pretended that she had a right to listen and nod as if she knew what was going on.

Cordelia was not sure why Ellen rode out to meet her so often, when she could say so little, but she was glad for the company. Ellen was kind, but more than that, she was ordinary. Talking to her gave Cordelia a window into what was normal and what wasn’t. She could ask a question and Ellen would answer it without asking any awkward questions of her own. Most of the time, anyway.

It had occurred to her, some years prior, that not all parents could make their children obedient the same way that her mother made her, but when she tried to ask Ellen about it, to see if she was right, the words came out so wrong and so distressing that she stopped.

Something about today—the memory of the obedience or the fly or maybe just the way the light fell across the leaves and Falada’s mane—made her want to ask again.

“Ellen?” she asked abruptly. “Do you close the door to your room?”

Ellen had been patiently holding up both ends of the conversation and looked up, puzzled. “Eh? Yes? I mean, the servants go in and out of my dressing room, but I always lock the door to the water closet when I’m in it, because you don’t want servants around for that, do you?”

Cordelia stared at her hands on the reins. They were not wealthy enough to have servants, and there was an outhouse beside the stable, not a water closet. She pressed on.

“Does your family think you’re keeping secrets when you do?”

The silence went on long enough that Cordelia looked up, and realized that Ellen was giving her a very penetrating look. She had a pink, pleasant face and a kind manner, and it was unsettling to suddenly remember that kind did not mean stupid and Ellen had been talking to her for a long time.

“Oh, Cordelia . . .” said Ellen finally.

She reached out to touch Cordelia’s arm, but Falada sidled at that moment, and Penny took a step to give him room, so they did not touch after all.

“Sorry,” said Cordelia gruffly. She wanted to say Please don’t think I’m strange, that was a strange question, I can tell, please don’t stop talking to me, but she knew that would make it all even worse, so she didn’t.

“It’s all right,” said Ellen. And then “It will be all right,” which Cordelia knew wasn’t the same thing at all.

2

A week later, Cordelia’s mother went into her large wardrobe and took out one of the dresses in rich, stunning fabrics, nothing at all like the faded gowns that Cordelia normally wore. Evangeline took a scarlet riding habit from among the dresses and it was as if she became another person as soon as the fabric touched her skin, a softer, sweeter one.

“Dear child,” she said caressingly, stroking her hand over Cordelia’s hair. “I’m off to see my benefactor.”

Once or twice a month, she would mount Falada and ride away and be gone overnight, and return with money, or with jewelry that could be sold in the city for money, to pay for bacon and flour and the services of the laundress in the town.

Cordelia knew full well that her mother was visiting a man, and that such things were not considered respectable. But this was how they survived and lived so comfortably. And besides, it was so much easier to be in the house when her mother was gone, as if she could finally draw a breath all the way down to the bottom of her lungs.

She watched from the window as her mother rode away, the scarlet fabric lying across Falada’s hide like a splash of blood on snow. Cordelia thought, as she sometimes did, about simply walking away, down the road. She wondered how far she could get, and if her mother would find her again. Not without Falada, though. I can’t just leave him here.

Instead, she sat in the kitchen and peeled potatoes. There was something very centering about peeling potatoes. She looked forward to having the whole evening to sit and think whatever she wanted and not be interrogated about what she was thinking or why she had any particular expression on her face.

Which was why it was such a shock when, barely an hour after she’d left, Cordelia’s mother slammed through the door, breathing hard, with her eyes like shards of broken ice.

Cordelia was so startled that the knife slipped and she gashed her thumb. She shoved it into her mouth, tasting copper and salt on her tongue.

The smell of wormwood swirled around her mother as she stalked into the kitchen. “Can you believe this?” she snarled.

Cordelia shook her head hurriedly, even though she had no idea what had happened. It was probably just as well that she had her thumb in her mouth, because otherwise she would have said something, and she was fairly certain that whatever she said would be wrong. As it was, her mother lifted her eyes and said, “Why are you sucking your thumb? You’re too old for that.”

“I cut it,” said Cordelia, hastily yanking it out of her mouth and hiding it in her apron.

“Hmmph.” Her mother stared at her broodingly for a moment, then looked away. Almost to herself, she said, “I should have killed him right then.”

Cordelia froze. She’d never heard her mother say anything like that before.

“I could have. I could have made him obedient and had him chop his own legs off with an axe. But that woman was there and there were servants and they’d have noticed.” Cordelia gulped. “Bah.” Her mother stalked toward the stairs, still muttering to herself. “I should have made Falada kick the bastard’s head in . . . no, they’d want him destroyed, and what a mess that would be . . .”

The image of Falada’s white legs coated in gore turned Cordelia’s stomach. She knew that she should feel much more strongly about the man who would have been killed, but he was a stranger and Falada was her friend. And if Mother made him kill someone . . . if she made him obedient like she makes me . . . then he’d be a dangerous horse and people would demand he be put down.

She slipped out to the stable, feeling ill. Falada stood in the dim stall, shining like a beacon in the dark.

“I didn’t know she made you obedient too,” Cordelia whispered. “I’m sorry. I should have thought.”

He swung his head toward her and she wrapped her arms awkwardly around his neck, the way that she had ever since she was a child. “I’m sorry. I didn’t know, and you couldn’t tell me.” She felt very small and selfish.

“I won’t let her hurt you,” she whispered, even though she knew that she had no power to stop it, and Falada pressed his nose against her shoulder and let out a long sigh.

* * *

At dinner that night, her mother was in a strangely merry mood. The best meat was waiting on the counter when Cordelia went down to cook, and her mother even offered to help.

Her mother’s good moods had once been more difficult to live with than the bad ones. Cordelia had dared to hope that things would change, that all would be better, that there would be no more obedience, and the weight of her hope had crushed her beneath it. Now she no longer had such illusions. But the respite was welcome, however brief, and perhaps it meant that her earlier mood, and desire for violence, had passed.

As they sat down to dinner, her mother sighed. “There’s no hope for it. He’ll be useless now.”

Cordelia often thought that when her mother talked to her like this, she was really talking to herself. Her job was only to nod at the appropriate places.

“Since I won’t be wasting my time with my benefactor anymore, and there aren’t many rich men here, we’ll have to move soon.”

“That’ll be interesting,” said Cordelia, which was a statement almost as neutral as silence.

When she turned back to the table, her mother was looking at her. Staring at her, not merely letting her eyes pass over her, the way she sometimes did. Cordelia felt herself growing still, as if her mother’s gaze was a wasp that had landed on her skin and any motion might incite a sting.

“How old are you now?” her mother asked abruptly.

“Fourteen and a half.”

“Fourteen and a half . . .” Her mother drummed long fingers on the table. “I had hoped to wait until you were a little older. Men don’t like women to come to a marriage with a half-grown brat in tow. Still, it can’t be helped. I’m not getting any younger, as my benefactor so kindly pointed out.”

Cordelia knew better than to agree with a statement like that, and said nothing.

“I can probably still pull in a merchant, though. Not one of the great houses—they all want young blood. But one with money enough to keep us in comfort until you marry a rich man of your own one day . . .” She shook her head. “It’s so frustrating, the money one needs to kit oneself out, to get into the right circles.”

“Surely rich men would love to marry you, though,” said Cordelia. It was a compliment, not a question, and that should be safe, and might prompt more information.

“Oh, certainly they would want to,” her mother said carelessly. “But their families wouldn’t stand for it. Selfish beasts. If I could use magic as I wished, I could have any man in the country. But wedding ceremonies break spells.”

“I didn’t know that.”

“Oh yes.” Her mother pursed her lips, clearly annoyed. “Water, salt, and wine, on holy ground. It is most inconvenient for sorcerers. That’s why I never wasted my time trying to ensorcell a suitably rich husband.”

Sorcerer.

Cordelia sat very still, the thought hanging inside her head like a bedsheet on a line. My mother is a sorcerer.

She had known that her mother was different from others, that she was capable of things that others were not, but the word sorcery had not crossed her mind. The sorcerers she learned about in school were considered low, feeble creatures, charlatans who worked in magical deceptions, and that did not seem to describe her mother at all. A sorcerer might try to pass dried leaves off as coins, say, or make a cow’s milk go sour. There were no stories about them making someone obedient.

“It’s much easier to get a benefactor,” her mother was saying. “But of course if the spell goes awry, or the fool goes off to a wedding, well. They leave you much easier than husbands. Men are faithless.” She tapped her finger against her lips. “Perhaps I should marry a country squire with a title and a bit of money . . . yes, I think that might be for the best. Enough money to put you out on the marriage mart as well, like we always planned. And you are seventeen and will soon be married and out of the house. Remember that.”

“Yes, Mother,” Cordelia said, bowing her head. She wondered if she dared ask Ellen about sorcerers, or if her mother would somehow know, and how terrible the punishment would be if she found out. She went upstairs to bandage her cut, but her mind was full of dead men and gore-caked hooves and she could not close the door against it.

3

Hester came awake in the night because something had ended.

At first her sleep-fogged brain thought that it might have been a sound. Had there been rain? Had she woken because the drumming on the roof had stopped? No, there wasn’t any rain last night, was there? It was clear as a bell and chilly from it.

She lay blinking up at the ceiling, the posts of the bed framing her vision like trees. What had stopped?

Fear took her suddenly by the throat, a formless dread with no name, no shape, only a sense that something was wrong, something terrible was coming this way. Hester gasped, reaching for her neck as if to pull off a murderer’s hands, but there was only the darkness there.

She was in her own room, in her own bed, in her brother’s house that had been her father’s house and her grandfather’s before him. She knew exactly where she was. If it had been a nightmare, she could have shaken it off, but she was firmly awake now, and the dread was not receding.

Something was coming. It would be here before long. Not tonight, perhaps not even tomorrow, but soon.

Ah, she thought, remaining calm even in her head. It was my safety that ended. Yes, of course.

Hester had felt such a nameless fear once before in her life, when she looked into the eyes of a young man that her parents had picked out for her. She had gathered her courage and cried off the wedding. It had cost her dearly but she stood her ground in the face of all opposition. Her parents had raised her to be good and biddable and not cause a fuss and it had shocked both them and Hester herself to learn how much stubbornness she had saved up over the course of those years.

Years later, when the young man’s proclivities came to light, she was held to have had a lucky escape. By then, of course, it was much too late. She had been branded a jilt and she was not beautiful enough to tempt any other suitors, nor was there enough money in the family coffers to tempt their pocketbooks. She had been considered firmly “on the shelf” by the time that word came down of what he had done, and the hanging that had followed.

Her father had apologized. Her mother hadn’t, but Hester had no longer expected such things.

This had the same taste, the same sense that doom followed and she had only a little time to avert it.

“All right,” she rasped aloud. “All right. I hear you. I’m listening.”

Acknowledgment seemed to be all that it wanted. The dread released her and Hester gasped in air, feeling sweat oozing from her skin and soaking into the sheets.

She wished suddenly, powerfully, that Richard were there in the bed beside her. They had been lovers a decade earlier, and then he had offered her marriage and she had turned him down, not willing to have him sacrifice his prospects out of pity. He was Lord Evermore to most, with an immense estate and money enough to set half the matchmakers in the city baying at his heels. He needed an heir and a spare and a woman young enough to give him both.

Hester did not exactly regret that choice, but it would be so much easier now to roll over and shake him awake and tell him that she’d had a nightmare. His arms would close around her, and she would lean her forehead against his shoulder and breathe easier. It would have been good to have.

But I don’t have it. And whatever is coming, it seems that I will have to deal with it myself.

Hester sighed. She was fifty-one years old now, and her back ached and her knees ached and when the barometer plunged, she found it easier to use a cane. She did not want to be standing in the path of the storm.

And if wishes were horses, then beggars would ride, she thought, and rolled over, and tried to get a little more sleep before something terrible arrived.

* * *

In the morning, Cordelia saddled Falada and rode him out of the stable. She took nothing with her, because she had not dared to plan anything in advance. She did not even dare to think about rebellion. She simply rode away, in the opposite direction from her rides with Ellen, staring at the road between Falada’s ears.

They went for perhaps three miles, as far as they had ever gone from home, and then Falada stopped.

Cordelia squeezed with her knees, and clucked her tongue. He did not move.

She got off his back and tried to lead him. “It’s all right,” she said. “Come on.” Her voice was shaking for reasons that she didn’t dare think about. “Come on, Falada, good horse.”

He did not move. She tugged on his halter and he set his feet in the road and did not move.

“It’s all right,” she told him. “We’re going away. You and me. So she won’t make you do anything that will get you killed.”

He might as well have been carved of quartz.

“We can’t stay. She’ll make you obedient again, and I can’t stop her.”

Falada did not stir a hoof.

“We’ll go another way,” she said, and tried to lead him off the road.

Again, he did not move. Not forward. Not back.

She tried to push him, with her merely human strength. He did not yield.

She actually thought about getting a stick and hitting him, but no. Not Falada. He was her friend, and you did not do that, not to animals, not ever. Some people used a riding crop, to be sure, but Cordelia would have cut her arm off before she put a mark on that shining hide. But I have to save him. I have to do something.

A lump was rising in her throat, and then her mother caught her shoulder and said, “What’s going on here?”

Cordelia whirled around, shocked. It took her a moment to say, “Mother? What are you doing here?”

“A very good question,” said her mother. “Where were you going?”

“I wasn’t—I wasn’t going anywhere. I wanted to see what was down this road—I’ve never gone—but Falada wouldn’t move—”

There was no way that her mother could be there by accident. She was miles from home. Her mother was on foot.

“Of course he wouldn’t,” said her mother, sounding amused. “He knew something was wrong.”

She stepped to Falada’s head and scratched under his chin with her nails.

Falada stretched out his neck and blinked his eyes and made a soft hwuff of pleasure.

“Were you trying to run away?” Evangeline asked.

“No!” said Cordelia. She hoped it sounded like shock. “No! If I was running away, I’d—well, I’d have taken food, wouldn’t I? Or water or clothes or something. And I wouldn’t! I mean, I love you. I’d never run away.”

Her mother laughed. Cordelia dared to hope that her answer had been good enough. Please, please, let her believe me . . .

She could not imagine the punishment for trying to run away.

“I know that’s not true,” said her mother. “He tells me everything, you know. He is my familiar, after all.”

It meant nothing. It was monstrous to the point of being meaningless. She did not know what a familiar was, but she knew that Falada could not possibly talk to her mother. She had whispered every secret and every fear into his mane and that would mean that her mother knew them all.

It could not be true, because the world could not be like that.

And then her mother stroked Falada’s nose, and he turned a sly eye toward Cordelia and snorted, and Cordelia realized that she was hearing the sound of a horse’s mocking laughter.

He thinks that’s funny.

He’s been telling her everything all along, and he thinks it’s funny.

The image came to her of Falada and her mother laughing at her together, and Cordelia thought that she might faint.

“Oh, don’t look so stricken,” said her mother briskly. “I’m your mother. Do you think I don’t know all your little secrets already?” She rolled her eyes and mounted Falada’s back, then reached down a hand to Cordelia.

Cordelia took it. She could not seem to breathe. The touch of calico under her arms, when she held her mother’s waist, was like sandpaper, and the sharp, woody scent of wormwood closed around her like iron bands.

“So you thought you were saving him, did you?” Her mother shook her head. “Silly child.”

“I . . . I . . .” Cordelia could not muster a single defense. Her mind was completely blank.

“I made you,” her mother said, looking straight ahead. “I made him and I made you, and you belong to me. Don’t forget it.”

They rode double back to the house. When they were cresting the final hill, the white outline of the house before them, her mother broke the silence, saying cheerfully, “You know I’d never let anything happen to you. Falada will keep you safe. He’d never let you get lost.”

Cordelia nodded. She’s rewriting it in her head already, then. I was getting lost, not running away.

Relief washed over her and settled in her chest. Her mother did this sometimes, recasting the past into a shape that she found more congenial. This time the changes seemed to benefit Cordelia.

The closeness between them, as she held her mother’s waist while Falada carried them toward their front door, gave Cordelia the courage to ask, “Mother? What’s a familiar?”

“Like a spirit,” said her mother. “Or a tame demon, sometimes. A sorcerer makes one out of magic, or catches one, or binds one. Falada’s mine.”

My mother is a sorcerer. Falada is her familiar.

She let those facts roll around in her head while they rode up to the stable. Falada’s hoofbeats were muffled on the packed earth floor.

“Are familiars all horses, then?” Cordelia asked, when she was finally allowed to dismount. She fought to keep her voice casual, as if it hardly mattered.

Her mother laughed. “No, and wasn’t it clever to make him one? So useful to have around. No, most sorcerers are so unimaginative, assuming they’ve got the power to call one up at all. Always nasty little devils with claws. And witches are worse—cats and dogs, the lot of them, not a drop of imagination between them.”

“Are there any others around here?”

Her mother’s head snapped up. “Why?”

Oh damn, damn, I shouldn’t have asked, I should have stopped at two questions, I shouldn’t have tried for a third . . . There was a look in her mother’s eyes that she didn’t like at all. She cast about wildly for an answer. “There was a dog that barked at Falada a few months ago. I thought maybe it was a familiar.”

This seemed to be a good enough answer. “No,” said her mother, turning away. “Falada would tell me if he saw one. There’re no other sorcerers around here, and the only witch is on the other side of town and she’s drunk half the time and senile the other half.”

Cordelia nodded politely.

“If you ever see another sorcerer when you aren’t with Falada, you must tell me at once, do you understand?” Her mother reached out and seized Cordelia’s wrist in a bruising grip.

“Y-yes, Mother.”

“Don’t trust any of them. They’ll only want to use you for their own purposes. And don’t even think about keeping it a secret from me.”

“No, Mother.” Cordelia had no idea how to tell if someone was a sorcerer, and struggled for a way to ask without making it a question. “I . . . I don’t think I’ve ever seen one. I don’t know what one looks like.”

Her mother sat back, lips pursed. “Hmm. No, I suppose you wouldn’t. I picked a good town to move to. Hopefully that luck will hold. Larger cities mean more sorcerers, and we want to avoid them at all costs.”

“Yes, Mother,” said Cordelia, who had pushed her luck as far as she dared.

She wondered, as she climbed the stairs to her room, what her mother had meant by “use you for their own purposes.” It seemed that there was little enough about her worth using, unless someone needed dishes washed.

A day ago, she would have said it aloud to Falada, turning the words over and trying to puzzle out the meaning. But a day ago the world had been different and Falada had been her friend, and tears slid down her face and dropped, unnoticed, onto the bed.

She tried to remember every secret she had ever whispered in Falada’s ear. There were too many, going back all the years of her life. Small ones, like tests failed at school, coins kept to buy a piece of penny candy. Big ones, like riding with Ellen.

How lonely she was. How afraid.

Even one secret was too many.

She felt as if she was coming up from being obedient again, and she swore that she would not scream.

* * *

Despite her mother’s statements, Cordelia was still surprised two days later when her mother announced that she would be marrying a man in a city near the coast and was going to go see to it. She left Cordelia a few coins and rode off on Falada, her chin high, while her familiar moved like silk beneath her.

Cordelia stood in the doorway and wondered what that meant. Would this man come here? Would she be expected to cook for three? She dreaded the thought. It would be very like her mother to come home with a guest and wonder why there wasn’t a steak dinner waiting on the table, and blame Cordelia for the lack.

Worse yet, she might be expected to talk to him. Cordelia dragged out her old primer from school, The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness, by Miss Florence Hartley, with its yellowing pages and firm, no-nonsense block letters. She read the paragraphs about how to speak to adults until she had committed them to memory. “Let your demeanor be always marked by modesty and simplicity. Avoid exclamations, they are in exceptionally bad taste and are apt to be vulgar in words. Above all, let your conversation be intellectual, graceful, chaste, discreet, edifying, and profitable.”

“Now, if only I knew how to make my conversation edifying and profitable,” she muttered to herself, embarking on a thorough cleaning of the spare bedroom, just in case it was required to hold a potential husband.

In the end, her mother vanished for nearly three days, and Cordelia actually slept with the door closed the second night. The only light came from the moon through the window. Wunderclutter hung in long chains from the upper sill, casting slithery shadows over her bed. It was supposed to drive off evil spirits and dark things that might walk in the night.

Cordelia wished that she could hang it all around the house and keep her mother away.

And Falada. Her stomach roiled with humiliation at the thought. Falada is worse.

The day after her mother left, Falada had returned, no rider on his back. Cordelia assumed that wherever her mother was, she had sent Falada back to watch Cordelia. Spy on me, more like.

He’d walked calmly from the road and into the stable, and Cordelia didn’t venture down there to check on him. She hadn’t ridden him since that day, and the loss felt like liquid filling her lungs, like she could no longer get a deep enough breath. She missed Ellen. She missed riding even more. Before, when it seemed as if the pressure under her skin would cause her to split open, she would have climbed on Falada’s back and galloped across the fields. Felt free for a little while, even if the ride always ended back at her house with its eternally open doors.

Now, when she felt that way, Cordelia gripped her temples and made a sound instead. Not a scream, which would have summoned her mother, but a small, shrill noise, like a teakettle whistling. Like the teakettle, it seemed to release some of the pressure.

With her mother gone, Cordelia could have really screamed. She tried it, experimentally, into her pillow, louder and louder, and then the scream broke into a laugh and she rolled over in her bed, feeling giddy and brave and wild.

It would not last, of course. Her mother would return, tomorrow or the next day or the next, possibly with a new husband in tow. But for the moment, the closed door was a balm and Cordelia slept deeply, without dreams.

4

Three days after her first panic-filled awakening, Doom appeared on Hester’s doorstep, in the shape of a woman.

Doom was tall and slender, with the sort of figure that poets described as willowy. She had shining dark chestnut hair and large blue eyes in a fragile, heart-shaped face, and she held the Squire’s arm as if she were too delicate to stand unassisted.

Hester noted dispassionately that Doom was beautiful. Hester was not envious, but beauty was a weapon that she did not wield herself, and it was not an insignificant one in the arsenal. Her brother was particularly susceptible to it, and even more susceptible to fragility.

“My sister, Hester,” the Squire was saying, gesturing to her. “Hester, love, meet our guest, Miss Evangeline.”

“Oh no,” said Doom. “It’s Lady, I’m afraid.” When the Squire tensed, she added artlessly, “Not that there has been a Lord Evangeline for a long time, I fear.”

Hester’s brother relaxed and patted the hand tucked into his arm. Hester did not roll her eyes, but she considered it.

“Your brother was kind enough to help me,” said Lady Evangeline, turning a brilliant smile on Hester. She lost the next few words as the sense of overwhelming dread clutched at her throat. “. . . quite overwhelmed. The city seems so much larger than when I was there last, and I fear I became quite turned around.”

“Mmm, yes,” said Hester noncommittally. I get it. I see her. You can let go now. Was her throat working? It seemed to be, although there was a definite rasp to it. “It’s grown a great deal in the last few years.”

“Exactly. I went looking for the dressmakers that I remembered, and they’ve quite vanished.”

“Asked her to stay for dinner,” said the Squire, in jolly tones. Hester suppressed a sigh. Her brother was smitten. This was a common enough occurrence, but generally by normal women, not those with dread and horror spread behind them like wings.

She would have liked to plead a headache and escape dinner, but that would mean leaving her brother alone with Doom, and that was a terrible idea. Hester wasn’t certain yet what Lady Evangeline intended, whether she was looking for marriage or money or something more straightforward, like human flesh. Regardless of which it was, her brother would be useless to deal with it. If the woman turned out to be a hag and suddenly ripped her skin off and flung herself, red and bloody, across the table to devour the Squire, the best that Hester could hope for was that one of the footmen might drown her in the soup course while the Squire was still gaping and waving his hands. And of course the footmen could do nothing about marriage at all.

You require a butler for that, thought Hester, and smothered her laugh in a snort.

“Beg pardon, my lady?” asked Doom, a line forming for just an instant between her china-blue eyes.

“Nothing,” said Hester. Steady on, old girl, you’ll laugh yourself into an early grave with this creature about. “Dinner, you say? I’ll tell Cook to prepare an extra place.”

* * *

It was astonishing that she had any appetite at all that night, with Doom seated across from her. Her brother sat at the head of the table, with Evangeline at his left hand and Hester at his right. “Just a cozy family meal,” the Squire assured their guest. “No need to stand on ceremony.”

Ceremony might have been nice, since it meant that Hester would not be expected to speak across the table at Evangeline. On the other hand, that means that I won’t be able to head Samuel off before he says anything truly dangerous. Not that he’s going to propose over the soup course. Probably. He likes beautiful women and he likes flattery, but he’s never shown any interest in marriage.

There had been several quite attractive ladies in her brother’s life over the years, including at least one that Hester would not have minded as a sister-in-law, but the Squire had always expressed disdain for “the parson’s mousetrap” as he called it. Like many men not overly encumbered by intelligence, he had a great deal of cunning in avoiding personal unpleasantness.

On the other hand, none of those other women had woken such a premonition of dread in Hester’s soul.

“So you are in town to visit a dressmaker?” she asked, when she felt that the flirtation going on between her brother and the widow had gone far enough.

“To make an appointment for a fitting, rather,” said Evangeline. “My daughter needs an entirely new wardrobe, I fear.”

“Your daughter?” This was an interesting new wrinkle.

“Oh yes. You know how it is with children,” said Evangeline, smiling at Hester. “They stay the same size for so long, and then they shoot up six inches overnight and positively nothing fits. She is seventeen, old enough to make her coming-out to society and I had planned around that, and then suddenly . . .” She made swooshing gestures with her hands and laughed aloud. “I swear that she looks like a servant now, wearing castoffs, but they are the only things that fit.”

“Indeed,” said Hester. “Why, I remember when Samuel was young, and my parents despaired of him. He would have a suit fitted, and then by the time he went to pick it up at the store, his ankles and wrists would be hanging out of it. In fact, one time . . .”

It was a timeworn anecdote, and she did not need to turn much of her mind to relating it. Instead she studied Evangeline.

Her manners were perfect, of course. Naturally, Doom would have exquisite manners. The only flaw, if you could even call it that, was that she was clearly not used to servants waiting on her. Occasionally she would catch herself just slightly as a footman replaced a dish, and she had reached out as if to pull out her own chair upon entering the room. But she recovered from these missteps instantly and with a great deal of poise, so much so that Hester was not entirely certain that they were missteps, or part of a carefully woven image of herself as a genteel but impoverished widow.

She could not escape the feeling that there was something very artificial about Evangeline. A physical artificiality, not merely her mannerisms. It had nothing to do with face paint or curling papers, either. Hester considered such things perfectly natural, even if she no longer bothered to use much beyond a little powder herself. No, it was something deeper and more fundamental. Hester could not escape the odd feeling that if she peered closely at the woman’s scalp, she would see hundreds of tiny holes where all that chestnut hair had been glued in, like a porcelain doll. She remembered her earlier flippant thought about the woman ripping her skin off during dinner. Suddenly it seemed much less amusing.

“Sister?” said the Squire.

“Eh?” Hester realized that her brother had been speaking. “What was that? You have to speak up, my hearing’s not what it was.” (This was entirely untrue, but she had found that it was a very good excuse when she had simply been ignoring a dull conversation.)

“I was saying that we must have Evangeline and her daughter down to stay with us, while they are waiting on the dressmakers.”

“It’s far too kind of you to offer,” said Evangeline, looking up through her eyelashes. “I couldn’t possibly impose.”

“Nonsense,” said the Squire. “What do you say, Hester, old girl?”

The old girl in question would have very much preferred to say no, but she did not. She knew that Doom would not be put off so easily. “Of course,” she said instead, reaching for her wineglass. “I should very much like to make your daughter’s acquaintance.”

* * *

Cordelia woke because her mother was shaking her awake. It happened often enough, but it seemed early. When she looked groggily out the window, the sky was still dark. “Is it morning?”

“Close enough,” said her mother. “Up, up!” She pulled back the blankets covering Cordelia.

“Today is the day we get out of this wretched town,” her mother said. Her eyes were shining and her skin was flushed and she looked young. “At last! Small-minded people. I’ll be glad to leave. Now pack your things and get in the carriage. We shan’t be back here.”

Cordelia blinked at her. It had just occurred to her that her bedroom door had been shut and her mother hadn’t said a word about it. This was unprecedented in her experience. “We haven’t got a carriage,” she said, and then softened it so that her mother would not think she was arguing. “Have we?”

“It’s a cabriolet,” said her mother. “Or perhaps a sulky. I can never remember the name.” She laughed carelessly. “Just big enough for two.”

“Where are we going?”

“To the coast. To the home of Squire Samuel Chatham, a ridiculous old man who will fall over anything in skirts, but who is old-fashioned enough to offer marriage if he thinks he’s thought of it first. I’ll be wedding him, and we’ll live in rather more comfort than we’ve managed here.”

Cordelia bowed her head. “We’re leaving now?” she asked.

“Not next week, silly child! The longer you dawdle, the longer this will take. We must arrive late enough that everyone is overwhelmed with pity for our long journey but not so late that everyone is asleep. Move!”

Cordelia obeyed. Her mother had provided a carpetbag and a bandbox. She packed her three dresses and two hats and her sewing kit and her daybook and pens, and the tiny carved wooden horse that Ellen had given her for her birthday years ago. It seemed unlikely that she would see Ellen again, and she wished there were some way to leave a note for her, but what would it say? Her etiquette primer said that letters of gratitude should be “simple, but strong, grateful, and graceful. Fancy that you are clasping the hand of the kind friend who has been generous or thoughtful for you, and then write, even as you would speak.” This advice did Cordelia no good at all, because she would have stammered awkwardly and probably said the wrong thing.

Thank you for talking to me and pretending I wasn’t strange.

No, you couldn’t write a note like that.

When she emerged with her bag, wearing her heavy coat against the cold, she saw the little two-wheeled carriage parked outside, Falada between the traces, and her heart sank. It was a cabriolet and she knew by the crest on the door that it belonged to Ellen’s father.

“This is Mr. Parker’s,” she said, in her most neutral voice.

“It was much too good for him,” her mother said. “We’ll sell it in the city.”

Cordelia swallowed. “Did he . . . did he give it to you?” She wanted to ask Did you steal it? but that would be an accusation and her mother did not respond well to accusations.

Her mother’s eyes were cold and bright, like fragments of sky reflected in a mirror. “He’s given me a great many things over the years. He didn’t want to part with the carriage, though, and I may have had to use some force.” She laughed and the sound was as cold and bright as her eyes. “Losing his carriage will be the least of his troubles now.”

Her benefactor was Ellen’s father? Cordelia’s mouth was very dry. Ellen had been her only friend, since Falada had proved false. And Evangeline had threatened to have Falada trample him to death, and if she was so pleased with herself, that could only mean that she had done something worse.

Guilt struck Cordelia all over, a cold rush from the soles of her feet up to her hair, and she clutched the carpetbag to her chest and bent over it.

“Don’t look so stricken,” said her mother sharply. “If not for having him as a benefactor, we’d have starved long ago. The problem is that men get bored so easily. Your father certainly did.”

It was all too much, too soon. “I thought my father was dead.”

“He is, and he brought it on himself, just as Parker did.” Her lips curved in a smile. She snapped her fingers and Cordelia knew that her mother’s patience was at an end. She climbed into the carriage with her carpetbag at her feet. Being made obedient would not help Ellen’s father, or expiate the sin that had, apparently, been going on for years.

I’m sorry, Ellen. I’m so sorry. Maybe I can write you a letter someday and tell you how sorry I am. She had written many letters in school, practicing her penmanship, though she had never sent one. Her mother had approved. Aristocratic ladies wrote letters to other ladies. It was a good skill to have, and so she had written out dozens of sample letters, thanking imaginary strangers for visits that had never occurred and gifts that did not exist.

None of the schoolbooks had a sample for when your mother had done something terrible to your friend’s father. Cordelia bowed her head and stared at her hands in her threadbare gloves. Her mother flicked the reins and Falada set out, pulling the stolen carriage as if it weighed nothing at all.

5

It was late and the fire had burned down in the grate when the butler announced that their guests had arrived. Hester would normally have gone to bed by now, but her presentiment of Doom was so powerful that she doubted she’d sleep anyway. She had a cup of hot cocoa instead, and sat by the fire, pretending to read a book.

“By Jove, you made it! I was beginning to think you weren’t coming.” The Squire rose, beaming, and no one could have guessed that he had been snoring gently but a few moments earlier.

“And miss your company? Never!” said Evangeline. “But oh, what a terrible trip we have had. I cannot tell you how glad I am to be here at last.” She smiled warmly at the Squire and held out both her hands. He took them, bowing over them, his smile even wider than hers.

“Misfortune on the road?” asked Hester. Her eyes picked out Doom’s shadow behind her, a young woman who seemed to be trying to fade into the wallpaper.

“Everything that could go wrong went wrong,” said Evangeline. “Our carriage threw a wheel in the rain and went