Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Lolli Editions

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

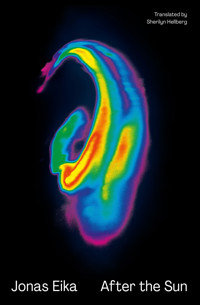

From a major new international voice, mesmerizing, inventive fiction that probes the tender places where human longings push through the cracks of a breaking world Under Cancún's hard blue sky, a beach boy provides a canvas for tourists' desires, seeing deep into the world's underbelly. An enigmatic encounter in Copenhagen takes an IT consultant down a rabbit hole of speculation that proves more seductive than sex. The collapse of a love triangle in London leads to a dangerous, hypnotic addiction. In the Nevada desert, a grieving man tries to merge with an unearthly machine. After the Sun opens portals to our newest realities, haunting the margins of a globalized world that's both saturated with yearning and brutally transactional. Infused with an irrepressible urgency, Eika's fiction seems to have conjured these far-flung characters and their encounters in a single breath. Juxtaposing startling beauty with grotesquery, balancing the hyperrealistic with the fantastical—"as though the worlds he describes are being viewed through an ultraviolet filter," in one Danish reviewer's words—he has invented new modes of storytelling for an era when the old ones no longer suffice. Praise for After the Sun Eika's prose flexes a light-footed, vigilant, and unpredictable animalism: it's practically pantheresque. After the Sun is an electrifying, utterly original read – Claire-Louise Bennett Eika says he 'started writing this book wanting to be surprised by it' and it delivers: this is a book that is hard to get out of your head, like an extravagant dream – The Guardian Relentlessly thrilling. The sentences in these stories stretch past the limits of the ordinary to the luridly extraordinary, and some moments feel as if they are breaking through to the sublime – New York Times Book Review After the Sun confronts modernity and alienation in hypnotic prose... These stories are compelling, haunted, even radiant – TLS Eika deftly exposes the absurdity and harm of class, capitalism, and global oppressive structures through glimpses into the lives of a wide range of characters and the way they do or do not cultivate connection or community… Utterly refreshing – BOMB Magazine After the Sun reads a bit like Thomas Pynchon taking on late capitalism. The writing is surrealistic, granular in its details, and concerned with social entropy and desperate attempts at communion… In a translation of unsettling intensity by Sherilyn Nicolette Hellberg, the stories derive much of their force from their insistence on transformation. Not only do the settings and characters abruptly alter, as in a dream, but the mood can instantly switch from light to dark – Wall Street Journal JONAS EIKA (b. 1991) is one of Denmark's most exciting writers. His debut novel, Marie House Warehouse, was awarded the Bodil & Jørgen Munch-Christensen Prize for emerging Danish writers in 2016. After the Sun was awarded the Nordic Council Literature Prize in 2019, as well as the Michael Strunge Prize, the Montana Prize for Fiction, and the Blixen Literary Award. SHERILYN NICOLETTE HELLBERG has published translations of Johanne Bille, Tove Ditlevsen, and Ida Marie Hede. In 2018, she received an American-Scandinavian Foundation Award for her translation of Caspar Eric's Nike.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 211

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

After the Sun

Praise for After the Sun

“Eika’s prose flexes a light-footed, vigilant, and unpredictable animalism: it’s practically pantheresque. After the Sun is an electrifying, utterly original read.”

– Claire-Louise Bennett, author of Pond

“Political fictions aren’t supposed to be this personal. Satires aren’t supposed to be this heartbreaking. Surrealism isn’t supposed to be this real. Giving a damn isn’t supposed to be this fun. From slights of hand, to shocks to the heart, After the Sun is doing all the things you don’t expect it to and leaving a big bold mark in what we call literature.”

– Marlon James, author of Black Leopard, Red Wolf

“Striking literary craftsmanship in an experimental mix of shock-lit, sci-fi, dada and Joycean glints presented as loose time scenes that slide in and out like cards in the hands of the shuffler. By the end, this reader had the impression of having been drawn through a keyhole.”

– Annie Proulx, author of Barkskins

“Jonas Eika blew the doors and windows of my imagination open, and now there is a galaxy in my head and a supernova in my heart. After the Sun vibrates with the aftershock of capitalism and reality flux. Its characters confront the world we’ve made as if they are facing off with ex-lovers who won’t leave, caught at the instant before they will either flame on or flame out. Thrilling.”

– Lidia Yuknavitch, author of The Chronology of Water

“An urgent, deliriously discomforting reflection of how we’re all connected with one another — and what it is we expect in exchange for that kind of access. Eika holds nothing back in his fiction, he goes into the tightest of spaces and most intimate and terrifying of moments in order to break through to places few have been before — or even imagined existing.”

– Refinery29

“Five surreal, globe-spanning stories shape Eika’s startling English-language debut. Studded with shockingly visceral images, these lyrical stories are preoccupied with a sense of psychosexual loneliness that penetrates even the most absurd moments of escapism. Eika’s fusing of the magic realist mode with the alienation of modernity makes for a winning formula.”

– Publishers Weekly

“The young Danish author Jonas Eika completely destroys every safety net: his book After the Sun has a combustible power in its longing for another world — and it expands the term ‘fiction’. No other poet has exploded onto the scene like Eika in a long while.”

– Der Spiegel

“After the Sun has surprised and enthralled the jury with its global perspective, its sensual and imaginative language, and its ability to speak about contemporary political challenges without the reader feeling in any way directed to a certain place… There is a real sense of poetic magic. Reality opens into other possibilities; other dimensions. There is something wonderful and hopeful in it that reminds us how literature can do more than just mirror what we already know.”

– The Jury of the Nordic Council Literature Prize

“Spectacular… The stories read as sensual as they are cryptic, permeated with a heavy desire that can barely be distinguished from a spiritual longing.”

– Der Tagesspiegel

“The stories in Jonas Eika’s After the Sun are mysterious, apocalyptic and full of magic.”

– Wetterauer Zeitung

“Genius… To read Jonas Eika is to see a weird, transparent organism breathe. A shooting star from the heart of the craft. The way in which wild fantasy and extraordinary language awareness combine with radiant craftmanship is truly impressive.”

– Die Zeit

“Completely in love.”

– Kultunews

“A world that I long to visit again.”

– Sveriges Radio

“The execution is ruthlessly good, energetic, original.”

– Stavanger Aftenblad

“The world belongs to those who truly live in it. That is the moral of the story. And that is powerful.”

– Dagens Nyheter

“After the Sun revolves around a rumblingly dark and directionless desire, which is suddenly let loose and given shape. Eika recounts tender and intimate relationships, which are simultaneously not sexual, so much more than sexual, and nothing but sexual. These relationships are unmistakably queer, arising between men, between groups of people, and between that which exceeds the human.”

– Information

“An ambitious take on what it means to write ‘realistically’ in a time and place structured by a massive global economy, looking towards a future which, in many ominous ways, is already here.”

– Jyllands-Posten

Contents

Alvin

Bad Mexican Dog

Rachel, Nevada

Me, Rory and Aurora

Bad Mexican Dog

Alvin

I arrived in Copenhagen sweaty and halfway out of myself after an extremely fictional flight. Frankly, I would use that word for any air travel, but on this trip I had, shortly after take-off, fallen into a light feverish daze in which I relived a series of flights I had taken earlier in my life. First, there was the trip home from Nepal with my ex-wife, then-girlfriend, our first trip together, when we, maybe out of boredom, curled up in our seats and took turns miming various sexual scenarios that the other person had to guess and sketch on a piece of paper, which we tore into pieces and reassembled into new situations to mime again, so that the game could continue for eternities. In my daze there was also my departure from Copenhagen six years later, after she became pregnant around the same time that she had been cheating on me with a colleague, and I was so panicked and grieved by my jealousy — which seemed just as impossible to live with if the baby was mine as if it wasn’t — that I packed my things, went to the airport and said Málaga to the man behind the counter, for some reason I said Málaga. Additionally, I relived a flight home from a work trip a few years later, during which I was unable to work, to say a word to anyone, because I was completely paralysed by what I had seen from my window during take-off: Past the gates, overlooking the runway, there was an observation deck where kids of all ages stood with their parents watching the planes take off. At one corner, a woman stood with her back to the railing — long, dark hair in the frozen sun — looking at a man running toward her, across the deck, and as we flew past he fell to the ground as if shot by a gun. I couldn’t hear the gunshot, if one had even been fired, and the plane continued into the clouds with me sitting stiff in my seat for the rest of the flight, doubting what I had seen. What was uncomfortable, feverish, about the stupor in which I re-experienced these flights, was how it slid across the surface of sleep as if over a low-pressure area, into a zone in which I was vaguely aware of the original flight, the one I was on now, which for that reason was hidden somewhere underneath or behind: the cabin hidden behind, the food cart, my fellow passengers and the clouds outside the window hidden behind these past, recalled and also in that sense extremely fictional flights. I felt a hand on my shoulder and opened my eyes to a single-faced flight attendant. Everyone else had already left the plane. The cabin was quiet and empty. On the way out, I looked at the windows and the carpet, the overhead luggage compartments and emergency-exit signs, and I ran my fingers along the thick stitches in the leather seats. At passport control, I passed quickly through the entrance for EU citizens. I took the metro to Kongens Nytorv and hurried to the bank’s headquarters to make it in time for my meeting with the system administrator that afternoon. As I turned the corner, I smelled something mouldy and burnt, a mix of fire and vegetable rot, and when I saw the red-and-white police tape, I started walking faster. The building had collapsed and tall piles of marble, steel, pale wood and office furniture lay dispersed among other unidentifiable materials. Beneath the scraps I could make out the edge of a pit, places where the earth slanted steeply into itself in the way that lips sometimes slant into the mouths of old people. Three or four servers protruded between the floorboards and whiteboards; funny, I thought, since the floors had just been elevated in anticipation of rising sea levels. A police officer told me that the cause of the collapse was unknown, but most likely — given the blackout and the aftershock that had awakened most of the street — some kind of explosion in the power supply lines had opened the pit that the building was now sunken into. It had happened late in the night, no one was hurt. His eyes wandered as he spoke, as if he were keeping a look out for something behind me. Behind his head hung a thick swarm of insects, colouring the sky black above the wreckage. I called my contact at the bank and was sent straight to voicemail, walked to the nearest café and took a seat at the high table facing the window. I was eating a bowl of chilli when the door opened and cold air hit the left side of my face. A person came over and sat next to me. I looked up from my chili at his reflection in the windowpane: young man, mid-twenties, short dark hair parted to one side, tall forehead, round rimless glasses. I could see the street through him, but then again his skin was also pale in an airy way. ‘Hey, you,’ he said, and ordered what I was having. The smell of café burger filled the room when the kitchen door opened, and turned into sweat on the back of my neck. ‘Where are you from?’ the guy suddenly asked. ‘Um… here, actually,’ I said, looking down at myself, ‘but I’ve been living abroad for a while now. What gave me away?’ ‘Your clothes, your suitcase, your glasses,’ he said. ‘Everything, just your appearance, really. You’re not from here.’ ‘Have I seen you somewhere before?’ I said, and regretted it immediately, tried to explain that I didn’t mean him but his reflection in the glass, the way I was both seeing and seeing through him. He smelled like eucalyptus and some other kind of aromatic. A big group left the café, and then it was empty like the plane had been empty when I was awakened by the flight attendant, except that now the waiter was gone too and it was quiet in the kitchen. ‘I’m going for a cigarette,’ the guy said, getting up. ‘Do you have an extra?’ I asked, even though I didn’t smoke. He grabbed his coat from the rack and said yeah and I realised that he probably just wanted some air — so damn quiet in that café — and that he probably preferred to go alone. ‘Nice with some smoke out here in the cold,’ I said. He nodded and looked at me, his face blue-white in the frozen sun. I looked at our legs in the window and took out my phone to search for a place to stay. I was supposed to be staying in the bank’s guest apartment, that is, in one of the rooms that now lay in pieces, spread among other rooms. ‘Where are you sleeping tonight?’ he asked. I was going to say ‘at a friend’s,’ but that could get awkward if he asked me the address, and I couldn’t remember the name of a single hotel. ‘I’m not sure yet.’ ‘You can crash with me. Everything is booked because of that summit meeting.’ Neutral gaze, his blank eyes like metal bolts in the cold air. I looked at my phone. ‘You don’t need to check. I’m telling you the truth.’ He lived in an attic studio off Bredgade. The room had no moulding or stucco, its lines as sharp as the lines of his face when the light was dimmed. It shone from a floor lamp pointed upward, so that the ceiling was covered by a disc sun with two eyes in the middle from the filaments. There was a shower cubicle, a steel sink, a refrigerator and a hot plate, a double bed, two chairs and a trestle desk. The window was small, the cracks around it filled with sealant a shade whiter than the yellowish walls. The narrow sides of the room were bare of furniture, but one of the walls was blanketed by a spangled sheet of packaging; empty sweets and crisp packets, cereal boxes, paper and plastic wrappers from lollipops, chewing gum, snack sausages and soda bottles, all from brands unfamiliar to me, as if they had been collected in a parallel universe, where every product was slightly different from the corresponding one in our world, so that you could recognise something as, for example, a chocolate bar, but at the same time find that word an inadequate denomination of it, because you were encountering the object for the very first time, and it was glowing, the wall was glowing with colours I had never seen before. ‘Souvenirs,’ said Alvin, because that was his name, and threw his coat on the back of a chair. I did the same. Alvin sat down on the bed and pulled off his shoes, and I did the same. ‘Nice and warm in here,’ he said as he removed his socks — sweet heavy smell of winter feet — and laid them on the radiator. The room was about two hundred square feet, and so sparsely furnished that you couldn’t help but register every movement. I looked up and noticed a small, metallic bottle with white waves down its body and a soft plastic straw, sewn into the fabric that held all the wrappers together in a mottled thicket against the wall. This dull and characterless object, whose purpose was to contain and be emptied of a liquid called POCARI SWEAT, shone before my eyes with a brilliance that was wildly enticing. I blinked and felt suddenly exhausted, like after a long illness. ‘I think I’ll take a nap — if that’s okay with you?’ ‘Make yourself at home,’ Alvin said. I awoke from a nightmare in which I was being slapped by a floating hand — the rest of the body above the elbow disappeared into white fog — to the sound of Alvin in the shower. The curtain clung to his scrawny legs, itty-bitty, bulging chicken legs. As long as he’s not expecting anything in return, I thought to myself, before realising that he was doing just as he would if I weren’t there. It had a calming effect on me, like someone sprawled on a bed saying ‘I’m not afraid of you,’ and so I didn’t need to be afraid of him either. It smelled like eucalyptus. Alvin was quiet, only audible in the sound of water hitting his body and falling to the floor in splashes. Trying to be polite, I rolled onto my other side and was playing possum when he stepped out of the shower, and I waited another ten minutes before yawning and saying, ‘Nice with a little nap.’ ‘Take a shower. If you want,’ he said, and I did. Afterward, Alvin smoking at the desk with his back to me, I got dressed with the intention of taking a walk, but then realised it was three o’clock in the morning. Still no word from the bank. Alvin offered me a cigarette. I sat on the chair next to him and smoked. The program running on his computer resembled the internal operating system that I was here to help the bank install. When a company of that size purchased that kind of software, they also had to pay for someone to implement it, in which capacity I was to travel from Málaga to Copenhagen six times, this being the fourth. In fact, I appreciated travelling for work, even though it filled me with a sense of randomness, a suspicion that the buildings and the people and the vehicles around me could just as easily be some other ones. It was so random that I had gone to Málaga, and that there was, in Málaga, a company that specialised in the development of operating systems that many companies in the Scandinavian finance sector found to be sublimely compatible with their internal organisational structures, such that I, who spoke Danish and could also get by in Swedish and Norwegian, was hired as a software consultant, despite the fact that I lacked any actual experience in the field. It was as if the contingency of all the circumstances that sent me to Copenhagen or Bergen or Uppsala so thoroughly saturated my experience of those cities that it felt like I wasn’t really there. Sometimes my entire working life felt like one big coincidence, or like the inevitability of a network of connections that belonged not to me but to the market, the market of Internal Operating Systems. Alvin clicked between tabs listing various amounts, some of them substantial, some staggering, connected to ID numbers that referred to other numbers, and the screen glowed silver on his forehead. ‘Stocks,’ I said. ‘Is that how you make a living? Actually, I install operating systems for investment banking firms sometimes, but I could never imagine myself…’ ‘Derivatives,’ Alvin said. ‘I don’t speculate about the future, I trade it.’ ‘Bonds?’ I asked. ‘Well, let’s start with the farmer,’ he sighed, and told me about derivatives, those mechanisms which I now accept as a precondition for the economy, but which at that point made my brain press against my skull and my nose bleed. The farmer