Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

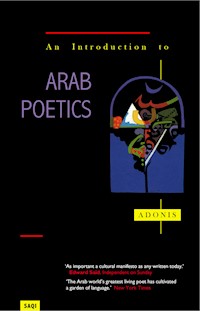

- Herausgeber: Saqi Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Poetry is the quintessence of Arab culture. In this book, one of the foremost Arab poets reinterprets a rich and ancient heritage. He examines the oral tradition of pre-Islamic Arabian poetry, as well as the relationship between Arabic poetry and the Qur'an, and between poetry and thought. Adonis also assesses the challenges of modernism and the impact of western culture on the Arab poetic tradition. Stimulating in their originality, eloquent in their treatment of a wide range of poetry and criticism, these reflections open up fresh perspectives on one of the world's greatest - and least explored - literatures.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 149

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

AN INTRODUCTION TOARAB POETICS

AN INTRODUCTION TOARAB POETICS

Adonis

Translated from the Arabicby Catherine Cobham

Saqi Books

Contents

Preface

1. Poetics and Orality in the Jāhiliyya

2. Poetics and the Influence of the Qur’ān

3. Poetics and Thought

4. Poetics and Modernity

Notes

Index

Preface

I first became interested in the theoretical aspects of writing poetry in the 1950s, the decade which saw the founding of the periodical Shiʿr (Poetry) in 1957 in Beirut. It soon became obvious to me that the prevailing critical outlook, especially in the universities and other educational establishments of the Arab world, was the product of a functionalist view of poetry. As a result, poetry had a semi-organic relationship with the establishment and its religious and social values. This was an approach which examined poetry — by its nature, concerned with the innermost depths of things — from the outside, except that paradoxically it was concerned more with the content of the verse than its manner of expression; in addition, this approach imprisoned Arabic poetry within an excessively rigid framework, so that it appeared to have nothing in common with any other poetry.

At the same period I decided to read the actual texts of Arabic poetry without reference to what the critics, ancient or modern, had written about them — something which took me about ten years. It became clear to me then that the prevailing interpretations of poetry were completely dependent on the power structure, which in turn was bound up with the religious establishment. In the texts themselves, however, there is scope for a pluralism of interpretation, confirming that Arabic poetry is not the monolith this dominant critical view suggests, but is pluralistic, sometimes to the point of self-contradiction. It is hard to imagine a more superficial, trivializing view of poetry, and one less conducive to an understanding of the poetic experience, than that which has long prevailed in the Arab world.

My reading also made it clear to me that, apart from the disparities resulting from linguistic and social peculiarities or from chronological differences, the artistic and cultural problems posed by writing poetry in Arabic are the same as those encountered in other societies.

Eventually I felt compelled to try to present Arabic poetry from another perspective, one which I have set out at length in the introductions to the three parts of Dīwān al-Shiʿr al-ʿArabī (Anthology of Arabic Poetry), and also in Muqaddima li’l-Shiʿr al-ʿArabī (An Introduction to Arabic Poetry).

I had become still more certain of the view of Arabic poetry which I was attempting to formulate when, at the beginning of the 1970s, I embarked upon a study of Arab culture as a whole which I called al-Thābit wa’l-Mutaḥawwil: baḥth fi’l-ittibāʿ wa’l-ibdāʿ ʿinda’l-ʿarab (The Fixed and the Changing: A study of conformity and originality in Arab culture). This was published in three parts (with a fourth part in preparation), with the following subsidiary titles: al-Uṣūl (The Roots), Ta’ṣīl al-Uṣūl (Establishing the Roots) and Ṣadmat al-Ḥadātha (The Shock of Modernity).

The lectures I delivered at the Collège de France in 1984 (and which are published in the present volume) are thus the product of over a quarter of a century’s research into Arabic poetry and Arab culture.

I hope they may serve as a preface to the writing of a new history of Arabic poetry based on the language of poetry itself in its relationship with things, and in its movement and depth of perspective. At the same time, I hope that they will open another window for English poetry, on to the language and particular creative vision of Arabic poetry.

Paris, January 1990

1

Poetics and Orality in the Jāhiliyya

I use the term orality here in three senses: first, to mean that Arabic poetry at the time of the Jāhiliyya (the pre-Islamic era in Arabia) was rooted in the oral and developed within an audio-vocal culture; second, to indicate that this poetry did not come down to us in written form but was ‘anthologized’ in the memory and preserved through oral transmission; and finally, to investigate the characteristics of this orality in poetry and assess the extent of its influence on written Arabic poetry in succeeding periods, in particular on its aesthetics.

Pre-Islamic poetry was born as song; it developed as something heard and not read, sung and not written. The voice in this poetry was the breath of life — ‘body music’. It was both speech and something which went beyond speech. It conveyed speech and also that which written speech in particular is incapable of conveying. This is an indication of the richness and complexity of the relationship between the voice and speech, and between the poet and his voice; it is the relationship between the individuality of the poet and the physical actuality of the voice, both of which are hard to define. When we hear speech in the form of a song, we do not hear the individual words but the being uttering them: we hear what goes beyond the body towards the expanses of the soul. The signifier is no longer an isolated word, but a word bound to a voice, a music-word, a song-word. It is not merely an indication of a certain meaning, but an energy replete with signs, the self transformed into speech-song, life in the form of language. From this comes the profound congruence between the vocal and acoustic values of speech and the emotional and affective content of pre-Islamic poetry.

To start with, orality implies listening, for the voice appeals to the ear first of all. Orality therefore had its own art of poetic expression which lay not in what was said, but in how it was said. This was particularly important because, on the whole, the pre-Islamic poet spoke of what his listeners already knew: their customs and traditions, wars and heroic exploits, victories and defeats. Thus the poet’s individuality manifested itself in his manner of expression: the more inventive this was, the more he was admired for his originality. It was his duty to give to the collective, to the everyday moral and ethical existence of the group, a unique image of itself in a unique poetic language. In doing this, the poet was not expressing himself as much as he was expressing the group, or rather he expressed himself only through expressing the group. He was their singing witness, and therefore we should not be surprised at this paradox in pre-Islamic poetry: unity of content and diversity of expression.

Let us say that recitation and memory did the work of a book in the dissemination and preservation of pre-Islamic poetry.

If we go back to the root of the word ‘song’ (nashīd) in Arabic, we see that it means the voice, the raising of the voice and the recited poetry itself. Two basic principles of pre-Islamic poetry were that it should be recited aloud and that the poet himself should recite his own poem: as al-Jāḥiẓ (775–868) says, a poem sounds better from the mouth of its composer. The Arabs of the pre-Islamic period considered the recitation of poetry as a talent in itself, distinct from that of composition; obviously it was of considerable importance in drawing an audience and impressing them enough to hold them there — especially so since, at the time, listening was essential to the comprehension of words and to musical ecstasy (ṭarab). For, in the words of Ibn Khaldūn (1332–1406), ‘Hearing is father to the linguistic faculties.’ From this perspective, the better the recitation, the more profound the effect of the poetry.

Recitation of poetry is a form of song. The Arab literary tradition is full of signs confirming this. The poets who recite their work are often compared to singing birds and their verses to birdsong. ‘Song is the leading-rein of poetry,’ according to a well-known expression, while Ḥasan Ibn Thābit (d. 674), ‘the poet of the Prophet’, has an equally famous verse:

Sing in every poem you compose

That song is poetry’s domain.

Examples like these show the organic link that existed between poetry and song in the pre-Islamic period. This explains the significance of the claim that the Arabs ‘measure poetry by song’ or that ‘Song is the measure for poetry.’1 The critic Ibn Rashīq maintains that song was at the origin of rhyme and metre,2 and that ‘Metres are the foundations of melodies, and poems set the standards for stringed instruments.’3

Kitāb al-Aghānī (The Book of Songs) by Abu’l-Faraj al-Iṣfaḥānī (897–967), which consists of twenty-one volumes and took fifty years to compile, is the most striking proof that poetry in the pre-Islamic period was synonymous with recitation and song.

Ibn Khaldūn writes:

In the early period singing was a part of the art of literature, because it depended on poetry, being the setting of poetry to music. The literary and intellectual elite of the Abbasid state occupied themselves with it, intent on acquiring a knowledge of the styles and genres of poetry.4

Elsewhere he defines the craft of song as ‘the setting of poems to music by dividing the sounds into regular intervals’.5

The actual performance of poetry had its own rules in the pre-Islamic period which survived into later ages. Some poets, for example, recited standing up, while others proudly refused to recite unless they were seated. Some would gesture using their hands or their whole bodies, like the poetess al-Khansā’ (sixth–seventh century) who, it is said, rocked and swayed, and looked down at herself in a trance. Thus in orality there is a ‘meeting in action’ of voice, body, word and gesture.

Some poets dressed up to perform, as if the occasion were a celebration like a wedding or a feast. In later times poets would imitate the costumes of their pre-Islamic forbears and so affirm the unbroken link between past and present.

Among the poets known for the excellence of their recitation in the pre-Islamic period was al-Aʿshā (Aʿshā Qays, d. 629), later given the nickname ‘Cymbal of the Arabs’ by the caliph Muʿāwiya. There are many different explanations of this name: it was said that the musical quality of the poet’s performance transported his audience; that he sang out his poetry like a hymn of praise; that his contemporaries frequently sang his poetry; or simply that the name reflected ‘the excellence of his poetry’ or ‘the beauty of his performance’. All of them link the poetry to vocal performance and song, the same connection made by Farazdaq (641–732), who declared to the poet ʿAbbād al-ʿAnbarī (seventh–eighth century) after hearing him recite, ‘Your recitation makes me better able to understand the beauty of the poetry.’6

Song was a body whose joints were metre, rhythm and melody. The aural response depended on how well these parts worked together in performance — song was a discipline of the voice which required a corresponding aural discipline. The need to co-ordinate the various elements of song led gradually to the devising of special rhythmic structures.

Most scholars would agree that rhythm began in the pre-Islamic period with sajʿ (rhymed prose or rhyme without metre). Sajʿ was the first form of poetic orality, that is poetic speech following a single pattern. This was followed by rajaz, a type of metre made up of either a single hemistich like sajʿ, but divided into regular rhythmic units, or of two hemistichs. The qaṣīd (ode, poem) was the culmination of this development of rhythmic forms, and consisted of two rhythmically balanced hemistichs which took the place of the balancing assonances of sajʿ and rajaz.

The root of the word sajʿ contains a reference to song, and is used to denote both the musical call of the pigeon and the plaintive monotonous cry of the she-camel, alike in the one respect of being continuous, unvarying sounds. Hence sajʿ came to mean ‘proceeding in an even, uniform way’ and was adopted as a technical term to describe a form of rhythmic speech with end rhymes, like poetry, but no metre, and a quality of evenness and regularity and sameness in speech, such that every word in a sentence resembles the other.7

Technically there are three types of sajʿ:

1. In the same statement, the different parts balance one another and are of equal length, and the assonances are identical and fall at the same point in each part.

2. The statement is composed of two parts, and each word in the first part is assonant with the word corresponding to it in the second part. According to rhetoricians this is the most pleasing form of sajʿ as long as it is not forced or overdone.

3. The parts are equal and the assonance is to be found in sounds which are close, but not identical.

In the early years of Islam the use of sajʿ declined until the form had almost disappeared, perhaps because of its association with soothsaying in the pre-Islamic period. According to a ḥadīth (saying of the Prophet), Muhammad declared, ‘Beware of the sajʿ of the soothsayers,’ and he is said to have banned its use in prayer and discourse. However, it reappeared in later times and was used especially in literary prose such as sermons, epistles and maqāmāt, eventually with so much exaggeration and artificiality that it became no more than an empty mould.

The poem (qaṣīd) is composed of verses divided into two equal halves or two hemistichs. It is said that the root (qaṣada) here means to break in half and so the term qaṣīd refers to the actual shape of the poem which is in two columns. However Ibn Khaldūn believes that the term derives from the way the poet keeps starting new subjects, passing ‘from one sort of poetry to another, and from one subject (maqṣūd) to another, tempering the first subject and the ideas connected with it until it fits harmoniously with the next’.8 In an alternative explanation al-Jāḥiẓ writes that the qaṣīd was so named ‘because the composer [of the poem] creates it in his mind and has an aim for it (qaṣada lahu qaṣdan) . . . and strives to improve it. [The word qaṣīd] is formed on the pattern faʿīl.’9

The qaṣīd form was predominant perhaps because it was the best able to respond to the ‘needs of the soul’ as al-Jāḥiẓ puts it, and the most susceptible to being sung and recited.

The fact that each verse (bayt) in the qaṣīd is an independent unit relates to the demands of recitation and song and their effect on the listener and not, as some people believe, to the nature of the Arab mind which they claim is preoccupied with the parts at the expense of the whole.

It should also be stressed that the rhyme in the qasīd relates first and foremost to its musical performance. One of the conditions for its use was that it should not be there for its own sake but as an integral part of the texture of the verse, in harmony with the metre and sense and in no way an extraneous addition or superfluous padding. The rules concerning ‘the end of the verse’, the rhyme which had to be repeated at the end of each line throughout the poem, applied to both vowels and consonants: the ‘i’ vowel (kasra) and the ‘u’ vowel (ḍamma) were not supposed to be interchanged, for example; the same rhyme word was not to be repeated in the course of a poem, and each verse had to be independent in sense from the following one. All these conditions support the idea that rhyme was present basically for its musical qualities, that is for the vocal-rhythmic phrasing, and was not a mere grouping of vowels and consonants. It was therefore necessary for the repeated consonants to resemble one another, and for particular care to be taken with the final vowel sound because on it depended the quality of the psalmody. The rhyme gave to the verse and thence to the whole poem a harmony and symmetry which ensured that it possessed a spiritual, musical and temporal cohesiveness.

The characteristics of pre-Islamic poetic orality formed the basis for the major part of the criticism and theory of poetry in subsequent periods. Rules and criteria were evolved which still dominate not only the technique of poetry but the tastes, ideas and areas of knowledge reflected in it.

To study these questions exhaustively would require an entire history of Arab poetics, so I will restrict myself to discussing the three points which are the most relevant to my subject here: inflexion (iʿrāb), metre and the activity of listening.

It is important to note that the Arabs codified poetic orality, giving its conventions and practices systematic formulations, in the early years of the interaction between Arab-Islamic and other cultures, in particular Greek, Persian and Indian. The aim of this was to affirm, preserve and put into practice the rhetorical and musical specificity of the craft of Arabic poetry, thereby asserting its individual identity and that of the Arab poet. This eager pursuit of distinctiveness and specificity lay at the root of Arab intellectual activity during this period of social and cultural mingling between the Arabs and other peoples, especially in Basra (Iraq), the cultural capital, ‘mediator to the earth and heart of the world’, as an Arab historian has described it. Solecisms and mispronunciations had become widespread in the language. The Persians had introduced Persian words and some rules of grammar, as well as popularizing their music. Ṭaha Ḥusayn (1889–1973) characterizes the cultural situation at the time as a mixture of:

pure Arab culture based on the Qur’ān and related religious sciences, and poetry and the lexical and grammatical issues which it raised; Greek culture based on medicine and philosophy; and an oriental culture stemming originally from the Persians, the Indians and the Semitic peoples in Iraq.10

In this climate the rules of language were laid down for fear that solecisms and corruptions would creep into the Qur’ān and the ḥadīths.