13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

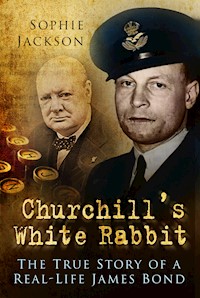

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Forest Yeo-Thomas GC was one of the bravest of the brave. A fluent French-speaker, he joined SOE and was parachuted into occupied France three times to work with the Resistance. Appalled by the lack of help the British were providing, he managed to arrange a five-minute meeting with Winston Churchill, during which he persuaded him to do more. On his third mission he was betrayed and captured by the Gestapo; he suffered horrendous torture before being sent to Buchenwald concentration camp, from where he eventually managed to escape, making it back to Allied lines shortly before the end of the war. Sophie Jackson's biography reveals new information about how the torture affected Yeo-Thomas, the state of SOE-Resistance co-operation, Gestapo typhus experiments at Buchenwald and how 'White Rabbit', Yeo-Thomas, provided the inspiration for Ian Fleming's famous secret agent, James Bond.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Contents

Title

Author’s Note

1 Beware the Agent who isn’t Punctual

2 The Secrets of a Tailor

3 A Heart for Conflict

4 The Ruination of France

5 An Ungentlemanly Type of War

6 The Man with the White Streak in his Hair

7 Good Agents Always Arrive Punctually

8 The American

9 Dinner with Sophie

10 A Good Agent has no Routine

11 Farewell, dear Brossolette

12 The White Rabbit and the German Wolf

13 The Endless Nightmare

14 The Traitor at Fresnes

15 The Darkness of Buchenwald

16 A Final Adventure

17 And then the War was Won

Select Bibliography

Plates

Copyright

- Author’s Note -

TWO PREVIOUS WORKS ON Forest Yeo-Thomas have significantly helped in this revision of his history. The White Rabbit by Bruce Marshal first appeared in 1952 and is the closest that can be come to an autobiography from Forest. It suffered from Marshal’s rather awkward prose and heavy-handed similes and was not entirely well received.

The second work, Bravest of the Brave by Mark Seaman, appeared in 1997 and delved into Forest’s personal papers to give a better understanding of the man and above all followed him post-war, which Marshal failed to do.

Both works, however, were inevitably one-sided due to restrictions on official SOE papers, which meant that they had to rely on Forest’s own words (recorded in unpublished memoirs) or the words of those who were closest to him.

Over the last decade the National Archives have gradually released SOE documents, in particular those relating to Forest’s missions and his personnel file, along with other papers, which enable a greater insight into this amazing man. New research has revealed more about his closest companions, such as Henri Peulevé, as well as opening doors into the Nazi regime. In particular the work of researchers to catalogue and publish the personnel files of the SS has enabled characters that Forest mentioned briefly to be fleshed out.

Among this new research was the discovery of a letter by Ian Fleming, never before published, that indicated his involvement with Forest.

This book could not have happened without the work of many others who have performed their own researches into the Second World War and published insightful accounts. It aims to take the efforts of Marshal and Seaman and build upon them to create a truly 3D image of a remarkable man. There is probably still much more to know about Forest, along with the many men and women who served with him, and only time will tell what new revelations will emerge from the archives.

– 1 –

Beware the Agent who isn’t Punctual

IT IS MARCH 1944 in Paris. SOE agent Shelley takes the familiar steps up to Passy Métro station ready to catch a train to Rennes. He is due to make a last contact with agent de liaison ‘Antonin’ to pass on last-minute instructions and an encoded message. The Métro station is the ideal place for a casual rendezvous. Since the Nazi occupation of 1940, cars have been virtually non-existent in Paris; aside from a ban on civilian motorists, most of the petrol stores were blown up in the invasion and what fuel is left has been secured for German use. Parisian citizens have had to fall back on other forms of transportation – the bicycle has seen a tremendous surge in popularity. But longer distances require faster transport and the Métro serves this purpose. The Nazis know that Paris cannot be brought to a standstill forever, so they ensure that the Métro runs smoothly and frequently. As Shelley saunters into Passy station bustling crowds instantly surround him. The platform is a hub of activity, filled with all kinds of passengers, and it affords solid cover for a clandestine meeting.

For the obsessively discreet Shelley, this is the perfect meeting point. He is a stickler for security. As part of his work in France developing the various resistance movements and coordinating them with British efforts, he often infuriates his espionage colleagues by drumming into them the need for strict protocol and utmost secrecy. He has come close to capture due to the recklessness of a resistance agent more than once. Others have died at Gestapo hands and whole resistance cells have been annihilated through the carelessness of a single individual. But as he calmly heads up the Passy steps that spring morning, he is unaware that his cover has already been blown – the last minutes of Shelley’s freedom are numbered.

Shelley has his last day in Paris perfectly mapped out. He leaves his apartment at 9 a.m. for an 11 a.m. meeting with Antonin, then he plans to have lunch with two women – ‘Maud’ Bauer and Jacqueline Rameil, secretaries to journalist and resistance member Pierre Brossolette. Brossolette has recently been arrested, though the Germans are ignorant of his identity and importance. Shelley is planning a rescue mission, and his visit to Rennes, where Brossolette is in custody, is part of this operation. At lunch with the ladies, he will discuss news of Brossolette, as ‘Maud’ is in close contact with the prisoner, masquerading as his mistress in order to get access to him in prison.

With his plans organised down to the last detail, Shelley is feeling confident as he arrives at the steps of the Métro, looking forward to a brief spell away from the constant and disturbing gaze of the Paris Gestapo.

Shelley walks nonchalantly up the station steps. His meeting with Antonin will appear to be by pure chance. Antonin has been instructed to signal that the coast is clear to Shelley by having his hands in his pockets – any deviation will mean that the encounter is called off. In the last few weeks Shelley has been tailed more than once, has seen ill-disguised Germans loitering outside his rooms and has even had to accost a contact who had failed to realise he had two Germans following him to a meeting. It is imperative that Antonin respects the danger they are in and acts accordingly.

Stopping by a newspaper kiosk, Shelley pretends to browse the few ‘patriotic’ papers and magazines. He is uncomfortably aware that 11 a.m. is rapidly passing with no sign of Antonin. Punctuality is another part of the ‘Shelley code’ – a late contact is a worrying sign. With any other agent, Shelley would have argued that the meeting should be aborted there and then, but at that crucial moment he finds himself torn with indecision.

Heading down the far side of the Métro station he pauses to consider his options: his principles tell him he should abort the contact and flee the station, but the information he is to pass to Antonin is so important that he is loath to give up so easily. Besides, he is due to be in Rennes for several days and he doesn’t like the idea of leaving without passing on vital instructions. The final nail in his coffin is the over-confidence that has been growing in Shelley since his first successes in France. He has outwitted the Gestapo on several occasions with the most audacious schemes, and lost tails and taken risks with seeming impunity. Right at that moment it seems as though Shelley has luck on his side, so he turns around and walks back into the station.

Glancing up the steps there is still no sign of Antonin, but Shelley heads upstairs anyway, and back to the kiosk, his contact point. The arrival of a train, which disgorges a large party of passengers, encourages him, and the commotion seems a good mask for his own clandestine activities.

Shelley is still on the stairs when, suddenly, five men break from the new arrivals and grab him. In seconds the stunned Shelley has his hands wrenched behind his back and handcuffed, while all around him train passengers scurry past and pretend not to notice. As his captors rifle through his pockets, Shelley spots the missing Antonin being escorted away between two Gestapo men. His heart sinks as he realises his hasty decision has led him straight into a trap.

Around him the Germans are yelling at the crowd to keep moving and threaten to shoot anyone who tries to intervene. The warning is hardly necessary as most Parisians are familiar with Gestapo tactics and are quick to avert their eyes from the scene. Shelley’s last hope is that he has only fallen into a security check, albeit a serious one, and that his captors have no real idea who is in their hands. But his hopes are dashed when elated Germans begin congratulating each other on the capture of ‘Shelley’, one of the top names on the Gestapo most-wanted list. As Shelley is forced through the Métro to a waiting car, his heart sinks further. He knows the game is up.

At SOE headquarters back in London, news of Shelley is slow in arriving and when it does come it is laced with misinformation and outright lies. It is not until May that dribbles of news, leaked from less-than-reliable sources, filter down the corridors in London. By that point, unbeknown to the SOE team, Shelley has already endured torture and is sitting in a prison cell wondering when he will be shot.

Early news suggests that Shelley is already dead. Rumours have it that on 21 March a tall Englishman with a moustache took poison while in German custody and the Germans tried to pump his stomach, but failed. Whoever this Englishman is SOE don’t believe it is Shelley based on the rather flimsy theory that he would have poisoned himself with cyanide (all agents carry the infamous death pills) and the Germans would have known it was futile to use a stomach pump with such a poison. Besides, they argue, Shelley is ‘fairly short’.

But other stories circulate that differ from the truth even more bizarrely. On the same cyanide report is another suggesting that Shelley had been on a mission to meet a woman called Brigitte. This was Brigitte Friang, secretary to Clouet des Pesrusches, another resistance operative. During this supposed meeting between Shelley and Brigitte, the secretary was supposedly shot by the Germans when she put her hand in her bag, as they assumed she was reaching for a gun. This was all said to have happened on the Passy Métro stairs, after which Shelley simply vanished.

In fact this story is a muddled rendition of two truths. Brigitte had been attending a meeting when she was shot in the stomach by Germans, however the meeting was not with Shelley, but with Antonin. It was later believed that the Brigitte meeting, held at the Trocadero, was what finally turned the tables on Shelley. At the meeting four Germans approached the pair, shot Brigitte and searched and interrogated Antonin. On him they found a document that broke yet another golden rule: it stated ‘Shelley Passy 11’ and told the Germans everything they needed to know about the planned rendezvous. How ecstatic they must have been to stumble onto a way of trapping the infamous Shelley so easily! They dragged the terrified Antonin to the Métro station and forced him to point out the man he least wanted to betray.

Even worse than the rumours and lies is the SOE’s misunderstanding of Shelley’s mission. Communication between agents and headquarters is notoriously difficult, as direction-finding vans operated by the Germans regularly scan for wireless telegraph (W/T) transmissions in France. The Germans have the great advantage of being in charge of Paris and are able to switch off the power to housing blocks whenever they choose; by doing this they can isolate a transmission and wait until it is abruptly stopped due to power failure to confirm where it is coming from. Then the search vehicles are sent out to find the errant transmitter.

In this hunted atmosphere agents are supposed to keep messages short and move their W/T sets to new locations frequently. Added to that complication is the need for personalised codes for agents based on letter replacement or the alteration of key words, with special false codes involving deliberate misspellings or the use of prearranged warning words in case of capture, and the arduousness of keeping London abreast of every development becomes apparent. SOE headquarters inevitably find themselves in the dark most of the time and such is the case with Shelley – they only have a vague idea of what he was doing on the Passy Métro stairs.

Some of their information comes from Shelley’s former secretaries. One cleared out his apartment after hearing that Brigitte had been shot and was puzzled to find no money; she assumed he had taken it in his suitcase to Rennes for the purpose of bribing people.

A second secretary received a typewritten note reading ‘CHEVAL est a FRESNES’: Cheval is at Fresnes. Cheval is an unofficial codename of Shelley’s used for secret communications with his secretaries, and Fresnes is a prison. Whoever sent the message is a mystery. It is unlikely to have been Shelley himself, but at least it goes some way to confirming his capture and where he is. His secretaries live in hope that the Germans are ignorant of Shelley’s real identity and that he has avoided the hardships of Gestapo interrogation.

Time, however, reveals the truth. An SOE agent, who is a close friend of Shelley’s and had seen him only four days before his arrest, arrives in England in May, going by the name of Polygone. He is interviewed by SOE and is able to give an accurate account of what has become of Shelley. British hearts despair as they hear that Shelley was arrested by the same Gestapo men who had shot another agent, Galiene II, quashing hopes that he had been picked up by accident. Polygone is damning of his friend’s security precautions and describes him as indiscreet. He carried a revolver in a holster at all times, which Polygone deemed unwise. Furthermore he had the dangerous habit of frequenting the same restaurants, but to allay the British disappointment at finding their best agent so fallible, Polygone assures them that on the whole Shelley’s security was good and he rarely carried important documents on his person unless absolutely necessary.

Unfortunately Polygone also knows that the Gestapo have raided Shelley’s apartment and it is widely thought that they have taken a microphotograph of Shelley’s mission orders and another document that includes a sketch of Shelley’s railway sabotage plans. Polygone is also concerned that at least thirty coded telegrams Shelley had sent to England have apparently gone astray; what has become of them no one seems to know, but with the Gestapo breathing down resistance necks, the missing messages are cause for grave concern.

SOE finally know most of the truth about Shelley’s disappearance. He is in the hands of the Gestapo, being held at Fresnes and more than likely enduring the worst kinds of interrogation the Germans can mete out. Rescue is an unlikely option as SOE takes the pragmatic view that they could easily lose more good men trying to regain one lost agent, and they simply do not have the resources for such high costs. Instead they begin to try to unravel where the blame for Shelley’s loss might lie. In any secret organisation betrayal is always at the back of people’s minds.

Polygone is of the firm opinion that there is an informer in their midst. He finds it highly alarming, let alone suspicious, that three agents de liaison have vanished at the same time as Shelley was arrested. One reappeared a month later but the other two remain unaccounted for. Then there is Antonin, who Polygone knows is missing but is unaware that he has been arrested with Shelley by the Gestapo. Lastly, a fifth agent de liaison who worked between Shelley and another important resistance member has vanished without a trace. Polygone cannot imagine that all these disappearances are pure coincidence and now SOE fear that they have a mole in their network.

This is not the first time that SOE’s French operations have been so badly compromised. Two of their resistance networks dealing with the introduction of Allied agents have in fact been completely infiltrated by the Germans and at least one has been operated and run by the Gestapo pretending to be a resistance network. On other occasions agents have been caught and forced to transmit false messages back to the British; sometimes this is spotted, but on many other occasions it is not.

Damage limitation is now key: whatever contacts Shelley made, whatever arrangements, need to be protected. SOE know that even the hardest of agents will break under the intensity of interrogation; there is a reason that the Gestapo use torture, even if it is considered a fallible system by more conscientious interrogators. The assumption has to be made that Shelley has been broken, and the relevant security precautions must be taken, especially if a traitor still loiters somewhere in the network.

Despite knowing that rescue is almost impossible, SOE continue to search for their lost agent. He is by no means the only one they are trying to track information on, but he is special in that he has a powerful reputation within the secret service community. Even a budding spy novelist working with the Admiralty is caught up with the mystery of Shelley’s loss and discusses it over dinner with colleagues. His name is Ian Fleming and he follows Shelley’s story with great interest.

SOE is rife with rumours about the missing agent. A telegram arrives with a strange jumble of information; the source is a member of a sub-unit of 72 Wing, engaged in wireless jamming operations. The source, in turn, heard his information from a liberated prisoner of war called Corporal Stevenson, who had been held in the Bad Homburg camp by the Germans. Stevenson had met a man going by the name Maurice Chouquet, who claimed he was actually SOE agent Wing-Commander Davies. Stevenson did not relate how he had earned Chouquet’s trust enough to learn such dangerous information (it was unwise for an SOE man to confide in anyone who was not also a known agent), but the significance of the message is that this could have been Shelley going by two assumed names.

Shelley is in fact making great efforts to convince his superiors and loved ones that he is still very much alive. He slips out whatever messages he can in the vain hope that they will reach home, and amazingly quite a few do. One finds its way into the hands of Sister Eanswythe of St Mary’s Mission. She comes by the information via her contact with Warrant Officer John Lander, a wireless navigator in the RAF who was shot down in early 1944. He had sent his son to the mission’s school before the war and regularly confided his family problems to the nun. When he failed to receive any post from his family during his confinement he complained in a letter to the good sister and asked her to see what she could do. In a short postscript he asked that she write to Mrs Thomas (Shelley’s wife) to let her know that he had met her husband and that he was alright. He failed to elaborate any further and SOE are disappointed that the nun is a dead end.

There are other letters, and SOE acquires them as soon as they can in order to analyse them. Agents are taught secret codes that can be innocently dropped into letters to family should they be caught, and Shelley’s letters are scrutinised for any clues. There is a feeling that SOE is clutching at very thin straws and their strained desperation even seeps into their analysis reports.

We are sorry, but [the letter to Mrs Thomas] does not contain a message according to the innocent letter conventions arranged here with [Shelley].

[However] it would seem that an investigation of the names and addresses [mentioned in the letter], and possibly replies, containing hidden messages on [Shelley’s] conventions might achieve good results.1

SOE is beginning to piece together a timeline of Shelley’s whereabouts during his absence. He has left clues wherever he can to let them know that he is still alive – scratched missives on walls, short messages, even contact with other British prisoners – but while they can pursue his route, SOE can do nothing to bring him home: that is up to the man himself.

But why is Shelley so important to SOE that they are pursuing him so diligently? Other agents vanish from official papers when captured, only being vaguely mentioned in a report about a more favoured agent. The files on Shelley are a bumper crop of information on one very special agent, but what made him so important? Who was he and why was his role so significant to SOE?

Note

1. Extract from interrogation report from Forest Frederick Edward Yeo-Thomas’ SOE personnel file.

– 2 –

The Secrets of a Tailor

SHELLEY’S REAL NAME WAS Forest Frederick Edward Yeo-Thomas, something of a mouthful, but a name that incorporated his French and British origins. Born on 17 June 1907 at a nursing home in Holborn, London, Yeo-Thomas was a child of two nationalities. Though British citizens, his parents, John and Daisy, spent the majority of their time in Dieppe, a tradition that went back to Forest’s grandfather, John Yeo, who had abandoned South Wales in the 1850s to travel to Dieppe and marry his sweetheart, Miss Thomas. The move had been spurred on by disapproving parents and to spite them further John incorporated his new wife’s surname into his own – the Yeo-Thomases were born.

The first Mr and Mrs Yeo-Thomas settled into Dieppe life, with John selling high-grade Welsh coal to the railways and securing his fortune; by 1895 they were so accepted within the community that grandfather Yeo-Thomas was able to form and become honorary president of the Dieppe Football Club, as well as becoming vice-president of the Dieppe Golf Club. Both his son and grandson were known as good amateur football players and in the 1960s players in the Dieppe area were still competing for a Yeo-Thomas Cup.

Despite being well integrated into the local French community Forest’s family still had strong British roots: they were ex-pats with firm loyalty to their king and country. A large photograph of Edward VII presided over mealtimes, inspiring obedience from Forest, who learned to sing ‘God Save the King’ as soon as he was able. When the king died his effigy in France was draped with black and the household remained in a state of mourning, talking only in whispers, for several weeks.

The influence of France could not be ignored, however. Forest spoke to his father in French, and it was natural that a child born into a foreign culture would tend to pick up its habits and quirks.

Forest’s parents chose to correct this by giving their son an education in England so Forest was sent to Westcliff School in Sussex, a typical boarding school and terribly English in its attitudes and methods. John hoped that this would instil some Britishness into his young son, but Forest was not the doting patriot that his father was, and Westcliff seemed totally alien to him. Switching cultures, despite the stern gaze of Edward VII looking over him since birth, was impossible for the young boy. He refused his school porridge in disgust and snuck out of his dormitory at night to sit on a nearby railway embankment to watch the trains. No doubt he was punished for his excursions, but Forest already had the stubborn streak that had taken his grandfather from Wales to France, and no beating could take that away from him. Fortunately his parents saw sense (or realised that it was hopeless) after a year, and he happily returned to France.

However, Forest’s French life was changing too. In 1908 a brother, Jack, was born and quickly became John’s favourite, pushing Forest further and further away. Forest attended the College de Dieppe in 1910, enjoying its naval links, before going to the Lycée Condorcet and the University of Paris. Forest was already favouring his French side and in Paris he studied history, eventually taking his Bachelier ès Lettres. His loyalties were now truly divided, with France’s influence being the strongest. The gulf between him and his father only increased his independence and made him favour French interests over British.

Forest may have felt awkward with his strange dual life, in essence living in two countries, but that would change with the First World War. The first advance of the Germans served to draw France and Britain together to stand against a common foe and suddenly being Anglo-French was a boon, rather than a disadvantage.

Naturally John Yeo-Thomas joined the British Army as soon as he could and quickly became a staff officer due to his fluency in French. Daisy also volunteered for the British Army as a nurse. While Forest felt proud of his family’s contribution, he could not have been unaware of the strain the war work put on his parents’ already fragile marriage. In fact Daisy and John were becoming virtual strangers to each other, a situation that only worsened when Jack contracted meningitis and died in 1917. John, devastated by the loss of his adored son, blamed Daisy for being too occupied with her war duties to properly care for the boy. In the bleak atmosphere that penetrated the family home, Forest saw one way out – joining the army.

His father was not oblivious to this desire and, understandably desperate to protect his remaining son, contacted both the French and British recruiting offices in Paris to make it clear that if a young Forest Yeo-Thomas were to arrive he was to be turned away for being underage. Forest was only thwarted for a short time, however.

The entrance of the Americans into the war gave Forest the opportunity he needed. The American troops were under-manned and under-equipped. Desperate for troops, their recruiting examinations were minimal, to say the least, and in late 1917 Forest joined up under the name of Pierre Nord, declaring he was 19, despite barely looking his real age of 16. He was accepted, and so Forest enjoyed his first success at subterfuge, which would become such an important part of his life later on.

Anyone who has even a passing knowledge of the First World War will realise the horrors that Yeo-Thomas was marching into – he could hardly have been unaware himself – but Forest was eager and determined. He was also lucky, which was a trait that would carry him through a second war. By 1917 the war was coming to its conclusion, not that the ordinary soldiers realised this, and life in and out of the trenches, the fears of no-man’s-land and the horrific death tolls seemed just as great that year as any year before. But Germany was weakening, and in another year they would be defeated and signing an armistice that would become the basis for grievances that would spur more conflict.

What Forest did in that intervening year is rather hazy. On the M19 questionnaire that he filled in when being assessed to be an SOE agent, he stated that he was in the US Army from 1917–22 and during that time visited Germany, Austria, Poland, Russia, the Balkans, Turkey and the USA. After the First World War it is thought that he joined an American Legion set up to assist the Polish in their fight against the Russians.1

Whether that is the case or not, Forest did end up at the battle for the city of Zhitomir and was captured by the Russians. As a foreign national he was automatically sentenced to death, but made his first impressive escape by strangling his guard and fleeing through the Balkans and into Turkey. He finally arrived in the USA to spend two more years in the army before leaving, as he stated on the M19 form, ‘to go into business’.

There is no doubt that this was a fabrication on Forest’s part and whatever his real reasons for leaving the army were, he kept them close to his chest. In reality, Forest returned to a France crippled by war, where many ex-servicemen found themselves unemployed and in desperate circumstances. Forest was no different: his parents had separated and John was involved with his former secretary (there was never a greater cliché) and was struggling to make ends meet. Some of his business investments had been tied up with Russia and after the Bolshevik revolution these had simply disappeared. There was little he could offer his son, and Forest drifted, at one point ending up selling bootlaces and matches in London. For the history graduate and war veteran it was demeaning.

Forest’s fortunes seemed to turn when his father managed to get him an apprenticeship with Rolls-Royce in 1922, but the economic climate saw even the mighty car manufacturer struggle, and Forest was let go.

Forest made another complete change of direction and went into accountancy. This seemed to suit him and for a time he was successful in the banking industry, serving as a senior cashier before moving on to be a business manager.

He needed the money his new job brought because in about 1924–25 he met Lillian Margaret Walker, a British/Danish national raised in France. He fell madly in love with her and they were married on 12 September 1925, and it wasn’t long before Forest’s first daughter, Evelyn Daisy Erica, was born in 1927. In 1930, a year after his parents had divorced and John Yeo-Thomas had finally married his secretary, a second daughter, Lillian May Alice, was born. In later records Forest’s daughters and wife would fade from memory and were virtually eradicated from military record, but in those hazy post-war days Forest seemed to have found some form of contentment.

Then, rather remarkably, he changed direction yet again. Giving up his banking career, he moved first to become an assistant general manager at Compagnie Industrielle des Pètroles, then made an even more radical change by joining the fashion house of British-born designer Edward Molyneux. It can only be imagined what pressures caused the change. France’s cracking political façade and the exhausted economy probably made a move into a thriving business seem sensible, but it is still interesting to wonder what Forest, a man who could strangle a Russian guard and partially build a Rolls-Royce, could have had to offer a fashion designer.

Molyneux must have liked his new general manager however, as Forest remained with the company until the outbreak of the next war. In the meantime he kept up his interests in sports by boxing, competing as a flyweight or bantamweight, and writing for the British magazine Boxing under the anglicised name Eddie Thomas. He was successful enough to hold a part share in a gymnasium and for the time being Forest looked set to follow a contented and successful career in the fashion world.

But all was not so rosy in the world of Yeo-Thomas. France was in turmoil as successive ineffectual governments crippled its economy, and Europe’s desperate fear of another war was leading to political appeasement towards the belligerent Germany, which was turning into a frightening power under the auspices of a hitherto unknown leader called Adolf Hitler.

While his business life was stable, Forest’s marriage was disintegrating. In a strange echo of his parents’ disastrous union, Forest and Lillian found themselves increasingly incompatible, and this little domestic war resulted in separation in 1936. Forest moved back to his father’s house, now run by his new stepmother.

Forest regularly met with Lillian to arrange money for his daughters. Divorce seemed the inevitable course for them, but even on this they could not agree. Forest was fearful he would be cast in the role of scapegoat and would lose access to his two young daughters, so when Lillian pushed for it he held back. Ironically when their roles were reversed and Forest sought divorce, Lillian was the one to oppose it, and as war loomed in 1939 they were still at an impasse. To add to his burdens, on 17 July 1939 Daisy passed away and Forest had to deal with arranging her funeral. His only consolation was that his mother would not see France crumble into war again.

The relative happiness Forest had experienced in the 1920s and early ’30s was now truly vanishing. The invasion of Poland thrust France and Britain back into conflict with Germany yet again, and for the fiery-natured Forest sitting on the sidelines was not an option. As war was declared he was preparing to sign up with whoever would take him but, just like in the First World War, it wasn’t so simple to find a unit that wanted him.

Note

1. Report by B Group to RF, dated 27 February 1945, the National Archives.

– 3 –

A Heart for Conflict

WAR BROKE OUT IN a Europe optimistically unprepared for conflict. Being forced to face reality also meant being forced to take stock of what they had and what they didn’t. One major service that had been neglected after the war was the intelligence division, but that was just the tip of a very large iceberg. Faith in appeasement had left Britain in a state of unreadiness and now it was necessary to pool what resources the country had and recall men who had experience from the previous conflict.

In France the situation was similar: disbelief at the dramatic turn of events seemed to be staying military hands, much to the frustration of Forest, who expected to be snapped up as a keen First World War veteran and volunteer. His aim was to join the British Army, but his first attempts via the British Embassy in the rue du Faubourg St Honoré ended in failure as no volunteers were being accepted. Annoyed, but not thwarted, he tried the French Foreign Legion, but they would not take on a British citizen, even if he did consider himself French.

It seemed that no one wanted Forest’s help, but he was not discouraged and returned to the British Embassy and made himself a nuisance to the air attaché until he finally accepted him as a volunteer driver under the condition that he supply his own car and petrol. Forest hovered uncomfortably between civilian and military status; he was neither one nor the other and his frustration was boiling over yet again.

All this would change on 26 September when he was finally accepted into the RAF as Aircraftman 2nd Class 504896, but his excitement quickly returned to disappointment when he was bluntly told that he would be serving as an interpreter as he was too old to fly. The irony that in a few short years he would be parachuting into rural France would probably not have impressed the RAF recruiting board. Forest, who had kept up his boxing and regularly sparred four to eight rounds with younger men, was angered by the implication, but the truth was that no one was particularly desperate for men as the war looked likely to be over before it had begun.

Perhaps the biggest problem was the desire not to fight that many felt and which acted as a psychological barrier to aggressive action. Britain and France, barely recovered from the First World War, did not want to enter into another conflict and there was a distinct impression of heels being dragged even as British forces crossed to France to support the defensive Maginot Line. Allied instinct felt that a quick, forceful assault, coupled with a blockade of German shipping, would result in sending the old Huns running back to where they came from. Unfortunately these weren’t the old Huns anymore, and strategies that might have worked a generation ago were now woefully out-dated. A hint might have come from the Germans’ easy defeat of Poland, but those in charge chose to be dangerously optimistic and the war effort crawled along rather than speeding to meet the threat. This period would become known as the Phoney War, the opening rounds when Britain and France both failed to realise the German might they faced and the risks ahead.

Forest was in the midst of this apathetic war. His role within the RAF seemed little better than when he was a volunteer driver and escorting VIPs and diplomats around and did nothing for his need to get into the action. But there was no real action. Even when Forest managed to get onto the Advanced Air Striking Force at Reims, which was supposed to be targeting Germany, he was disappointed to discover that they were not allowed to do anything unless the Germans hit first.

Forest had drifted into a hazy world of harmonious inactivity. The Reims authorities were as confused about the situation as their counterparts in Paris were, and the Phoney War had cast a fog over their bureaucratic preparations. Forest was posted to the interpreters’ pool, but when he arrived no one could tell him where he was supposed to go, so he found himself a hotel room and hoped to be able to locate his office in the morning. He was in luck, for the next day he bumped into an old friend, Sergeant Albertella, who was able to direct him to the Château Polignac where the interpreters were being housed. When he reached it he was in for a further surprise as he had been unexpectedly promoted to acting sergeant. This triumph was unfortunately tainted, as Forest was still acting as an ununiformed interpreter to senior staff officers. This made his position among the other officers untenable at times and Forest’s dislike for incompetent authority quickly became apparent. To one squadron leader who asked him to summon a pilot officer with the phrase ‘send that sod out there in’, he replied that he would be happy to oblige when the request was ‘properly expressed’, to which he got the response: ‘Of course, you’re not an officer and you can’t expect the same respect as I can.’ On another occasion, when this same man learned that Forest had been employed in the fashion industry, he announced: ‘My God, what is the RAF coming to!’1

Worse was that the air attaché’s original conditions that Forest pay all his own expenses still held true. Forest’s pockets were soon empty as he tried to keep up with his superiors. In an effort to recoup something, he collected receipts and sent them to the RAF for payment. Conveniently for the paymasters, they were lost in the invasion of France before they could be paid and they refused to listen to any further requests on the subject from Forest without seeing duplicate receipts. Even in war bureaucracy gives no quarter.

Forest was far from being alone in feeling that no one was really taking the war seriously, as this was the overriding feeling of many ordinary soldiers and airmen. It seemed that the authorities had blinkered themselves to the danger and were spinning out time until they had to do something decisive. Part of the problem was a need to hastily rearm, and both Britain and France had gone into a buying frenzy with the US to stock up on much-needed weapons and equipment. Meanwhile the RAF ran pointless sorties to Germany, dropping not bombs, but propaganda leaflets. Aside from a few odd skirmishes, the troops on the Maginot Line were enjoying a quiet stalemate. The real action was happening out at sea with the opening stages of the Battle of the Atlantic.

It was with nervous optimism that Forest joined the Forward Air Ammunition Park (FAAP) near Reims in the hope of carrying out duties more to his liking. He was at last given a uniform and it was with some relief that he realised he could be truly useful at the posting, using his bilingual abilities to create links between the military and the local population. Though he did not know it at the time, it would prove good practice for when he had to liaise between resistance groups and London.

Forest was perfect for the role, his natural charm and charisma as well as his confidence led people to instinctively trust and listen to him. He also slipped into the role of a leader easily and people automatically looked up to him. He might not have had the traditional good looks of a future secret agent – one author called him ‘terrier-like’ in appearance – but he radiated honesty and sincerity, which meant far more.

His time at FAAP was cut short when he was sent to attend an anti-gas course in England on 23 November. Forest had not been ‘home’ in seventeen years and, right at that moment with Germans on his doorstep, he was hardly in the mood for a sojourn abroad. He stepped into an England about to experience the harshest winter it had seen in forty-five years, with temperatures plummeting while Forest and four fellow NCOs sat through lectures at a camp on Salisbury Plain. At least the RAF lecturers impressed Forest, and there were some opportunities for fun and games. This included a car trip into Salisbury with a civilian employee on the camp. Forest and four of his companions agreed to the arrangement but were stunned when their charitable friend demanded 10s each for giving them a lift. Too keen to get out of the camp and into city life to argue, they paid up, though on their return Forest tried his hand at ‘wartime’ sabotage and put half a pound of sugar into the petrol tank of the man’s car. Salisbury had proved a pleasant break from the stalemate in France, but it was only to last a fortnight and Forest was soon back at FAAP.

It seemed that the military could still not quite decide what to do with him, and he was not the only one. Trying to keep men who wanted to be fighting occupied was not easy. Just before Christmas another training course was arranged, this time at Fighter Command at Stanmore, Middlesex. Forest had barely unpacked when he was ordered back to Britain in the bleak midwinter. It was not to be the nicest of trips as Forest found himself stuck aboard a transport ship in the middle of the Channel on Christmas Day, his mind returning to past Christmases with his family. He was still in touch with Lillian, though their relationship was now as cold as the ocean surrounding him, and Forest found himself suffering in his loneliness for the first time. Not a person prone to worrying about being by themselves or requiring someone to lean upon, he now found that his isolation was becoming uncomfortable.

Matters were not improved by his arrival at Fighter Command on Boxing Day, when he was abruptly sent away for another 48 hours of unwanted leave. Stuck in London with nothing to do and with the December weather biting at his heels, he would later remark: ‘I don’t think I have ever hated any place more than I did London that night.’2

When he returned to the RAF they yet again seemed to consider him surplus to requirements and, increasingly frustrated, he was sent off for another week’s leave. Forest now sunk into one his lowest ebbs; it was not until he found himself interned in a German concentration camp that he felt so miserable and alone again. He withdrew money from the bank, slept in several luxury West End hotels and went on a week-long bender.

It was while Forest was extinguishing his misery in various bottles of alcohol that another wartime volunteer, who would change Forest’s life, was also finding the Phoney War an inconvenience. This was Barbara Dean, born in Kent in 1915, partially orphaned when her mother died shortly afterwards and unloved by a father who blamed her for his wife’s death. Stubbornly independent and with plenty of opinions and a rankling dislike for authority, Barbara was almost Forest’s female counterpart. She was not a conventional beauty, but pretty and with a sense of flare about her appearance that summed up her personality. She was described by one contemporary as ‘one of the few exceedingly pretty women I have known who are also sweet and humble and charitable.’

While Forest was battling with temporary depression, Barbara was struggling to fit in with the WAAF. Spurred on by a desire to protect and defend her country, she had willingly volunteered for the service only four months before, but quickly discovered that military life was too uncompromising to suit her. Unlike Forest, who not only responded to the discipline of uniformed life but encouraged it in his later dealings with resistance members, Barbara could not stick being told what to do. For her it was all petty bureaucracy – pointless, stupid and infuriating – and she finally had enough when she argued with an officer about her hat being crooked and was put on a charge. Barbara ‘volunteered’ her way out and was waiting impatiently for the paperwork to be finished at the same time as Forest was kicking his heels in London.

There was always something that felt like the hand of fate, or perhaps lady luck, in Forest’s life, and his first meeting with Barbara has precisely that feeling. They could easily have missed each other by a few days and they weren’t even based at the same station, but on Forest’s return to Stanmore Forest, he discovered that he was being sent to the Bomber Liaison Section, where he would meet the woman who would sustain him through the war and beyond.

At Bomber Liaison, Forest was sent to the Filter Room, the secret control centre where all radar reports on hostile intruders were sent. The RAF had several of these Filter Rooms operating during the war, manned almost exclusively by WAAF members such as Barbara. There were strict rules for choosing operatives: ‘Must be under twenty-one years of age, with quick reactions, good at figures and female’ stated one criterion.3 Though these were obviously not always followed, as Barbara was 24. Still it was a decidedly young, female environment and a hub of activity.

The purpose of the Filter Room was what its name suggests – it filtered information from the various radar stations across the country. Raw data was sent in and was then checked and sometimes recalculated to compensate for human error. This information was then arranged on a giant table map – so familiar from old war movies where WAAF girls pushed blocks representing German planes around with long pointers – before being passed on to the Operations Room.

In a gallery above the WAAF workers, senior officers monitored the maps and acted according to the information present, whether that meant instructing air raid warnings to be sounded, scrambling fighter squadrons, alerting anti-aircraft defences or monitoring damaged homecoming planes that might be in need of assistance. It would be from this eyrie that Forest would operate and from where he could have a good bird’s-eye view of Barbara as she hurried back and forth.

Forest was surprisingly cautious in his attempts to attract Barbara’s attention; the disaster of his marriage and the fact he was not yet divorced probably damaged his confidence in approaching her, but he was still determined. On long watches in the Filter Room he would talk with Elizabeth Trouncer, a friend of Barbara’s, and try to surreptitiously draw out ideas on how to woo the elusive woman of his dreams. He prolonged these interrogations by taking Elizabeth out to dinner, but she was no fool and knew he was using her as a means to an end. Offended at being so obviously misled, she told him bluntly that he had no chance with Barbara; Forest shrugged this off and even wagered £5 with her that he could win the feisty Miss Dean over.