Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

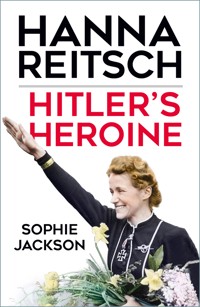

- Sprache: Englisch

Hanna Reitsch longed to fly. Having broken records and earned the respect of the Nazi regime, she was the first female Luftwaffe test pilot, and eventually became Adolf Hitler's personal heroine. An ardent Nazi, Hanna was prepared to die for the cause, first as a test pilot for the dangerous V1 flying bombs and later by volunteering for a suggested Nazi 'kamikaze' squadron. After her capture she complained bitterly of not being able to die with her leader, but she went on to have a celebrated post-war flying career. She died at the age of 67, creating a new mystery – did Hanna kill herself using the cyanide pill Hitler had given her over thirty years earlier? Hitler's Heroine reveals new facts about the mysterious pilot and cuts through the many myths that have surrounded her life and death, bringing this fascinating woman back to life for the twenty-first century.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 411

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Front cover illustration: Hanna Reitsch in her hometown of

Hirschberg. (German Federal Archives)

First published 2014

This paperback edition first published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Sophie Jackson, 2014, 2022

The right of Sophie Jackson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75095 723 6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Introduction

The Hanna Reitsch Who’s Who

1 Born to Fly

2 A New World

3 The Soaring Dream

4 Flying is Everything

5 Snow and Broken Glass

6 Giants of War

7 A Child of Silesia

8 Living with Disillusionment

9 The End of the World

10 When All Hope Is Lost

11 Adrift in Africa

12 Lost and Alone

Appendix 1: Letter from Dr Joseph Goebbels

Appendix 2: Letter from Magda Goebbels

Appendix 3: Selected World Records and AwardsEarned by Hanna Reitsch

Bibliography

INTRODUCTION

On the movie screen a petite Hanna Reitsch stares up with naïve wonder at the ranting man she has come to adore and idolise. Hitler rages in fury at Himmler’s betrayal before calming himself and revealing his final (and nonsensical) plan to save Berlin. Eyes wide in admiration, her voice a mere whisper, Hanna looks up. ‘I kneel down to your genius and before the altar of our fatherland,’ she says.

This sycophantic, sickening Hanna – cringe-worthy as she worships the man who has destroyed Germany – is very different from the confident, cocky aviatrix who struts across a different movie screen towards a modified V1 flying bomb. A death trap for previous pilots, the rocket plane stands with its cockpit open awaiting her. ‘There’s no point in your taking unnecessary risks.’ Hanna is told as she strides to the plane, ‘We’ve lost four pilots already.’ ‘I’ve got to find out why these damn crates won’t fly,’ she replies calmly.

The first Hanna appears in a German movie produced in 2004, Der Untergang (Downfall), played by the actress Anna Thalbach. The second Hanna appears in the British movie Operation Crossbow, produced in 1965, played by the German actress Barbara Rütting. Hanna is central to neither of these movies, but performs as part of a side-story. In Downfall she barely makes two scenes, in Operation Crossbow she features early on and then vanishes once she has tested the V1 successfully (it was Operation Crossbow that invented the myth that Hanna test flew V1s to find out why they were missing their targets). Yet the two performances are diametrically opposed to each other. The sycophantic, almost idiotic Hanna against the cool, self-assured, controlled Hanna. More than most characters of the Nazi regime she has become parodied to extremes, either viewed as a stupid girl who believed in Nazism or as a heroine of female flying. Even her name sparks controversy, far more than conversations involving other Nazi followers, such as Hans Baur, Hitler’s pilot. Over and over again Hanna is either derided and scorned or discussed in overly sympathetic and apologetic tones. Neither attitude does her justice, nor do they represent the real Hanna.

Delving through the myths, the propaganda, the hatred and the adoration, the real Hanna surfaces as a pale flicker of light; as a woman who wanted to make her mark at a time when the only people with power were Nazis. She has been called politically naïve; that is perhaps rather generous. Others have labelled her a hardened Nazi, which is perhaps too harsh.

Time has allowed historians to gain perspective. It has enabled more and more academic analysis of the realities behind the horrors of Nazism. Interest is now being paid to what is sometimes called ‘the ordinary Nazi’. The man or woman in the street who believed in National Socialism but not in the extermination of the Jews, who recognised the good Hitler had done for Germany – saving it from poverty, increasing employment, rejuvenating its cities and towns – and found it hard to level this with stories of persecution, cruelty and death. Much was hidden; much was not.

Some years ago, a Russian friend explained her own complicated views on Communism. When she was a child Communism had seemed the greatest thing imaginable. She was from a poor family, yet Communism enabled her to have ballet lessons, nurtured her potential and gave her hope. Only after coming to Britain as an adult did she begin to learn of its dark side. She started to study this ‘other’ Communism and realised that the society she had treasured for the opportunities it had given her was built on such secret cruelty, misery and corruption – it was almost unbelievable. It was impossible to reconcile this view with her own memories. Her happy childhood was now overshadowed by the knowledge that that happiness had been bought by murder and violence.

She is no different to the disillusioned National Socialist who had been spoiled by a system that was now turned on its head and exposed as brutal, desperate and barbarous. Culling people’s perceptions and memories, especially happy ones, is not easy. It is even harder when those people are suffering the shock and poverty of post-war Germany. Should it surprise any of us that those people might hark back to better times, when Hitler first came to power? Germany was torn to shreds, divided by concrete and guns and left to suffer like a wounded animal after 1945. During Hanna’s lifetime that suffering seemed unremitting, she did not live to see the destruction of the Berlin Wall or the flourishing of modern Germany. She saw only devastation – is it so hard to imagine that bitterness and sadness made her think of her glory days when Nazism was young?

In a recent interview the 80-year-old daughter of Rudolph Höss, notorious commandant of Auschwitz, defended her father as ‘the nicest man in the world’ because to her he was, and in comparing that personal image with one paraded to her by the enemy, no matter how true, the reality was impossible to accept.

Hanna had a similar view of Hitler. Always looking for a father figure in her life, she made Hitler her ultimate paternal guide. Affectionate and generous to her, kind and ready to promote her dreams, he was everything a girl could want. Joining this with his post-war image of villainy and corruption was difficult for her. She was disillusioned, hurt and very frightened. She was a girl without a father figure to support her (her own father sadly committed suicide, as did her other male mentor, von Greim). Yet Hanna did deny Hitler. It hurt her and she wished it to remain quiet, but she did tell Americans of his apparent mental collapse and the horror and the shame she felt after learning what had really gone on. She had plans to prevent Nazism resurfacing in Germany, she had hopes to build a brighter future; for this she was smashed down and abused.

Hanna has been harshly treated by many over the years, while her supporters have gone to the opposite extreme, glossing over her mistakes and making the matter worse. Somewhere between the two views lies the real Hanna, the woman who pioneered flying for women, who for many remains the greatest of test pilots. Who spoke her mind and often suffered for it. Hanna did not want pity; she just wanted to fly, that was all she ever wanted. She made bad choices, but no more so than other men and women within the Hitler regime who have been treated with generosity by history.

Why has Hanna drawn so much criticism? Why was she laughed at and shunned? What made her the villain of the piece when her actions within Nazism were very minor? Within Hanna’s story jostle an assortment of characters who had done far more to aid Hitler; from the man who created the V2 rocket, to the pilot who never lost his Nazi leanings. Hanna was no Nazi, but she was no innocent either. The story of the real Hanna is only slowly emerging and must compete with tall tales told about her exploits and cruel words spoken by one-time friends. This volume focuses on the person behind the label of Nazi Aviatrix, and naturally must delve most deeply into her involvement with Hitler during the war. This is not an apology for Hanna, nor a character assassination, but an attempt to portray a complicated person impartially. Along the way Hanna’s story exposes what life was really like for a woman with dreams in the Germany of the 1920s and 1930s.

THE HANNA REITSCH WHO’S WHO

Wernher von Braun: 1912–77

After the war von Braun gave himself up to the Americans and was taken to the United States under the secret Operation Paperclip. Von Braun worked on the United States Army Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile programme until it was incorporated by NASA. He then served as a director at the Marshall Space Flight Centre and was chief architect of the Saturn V launch vehicle used on the Apollo spacecraft for the moon landing. Despite his former allegiance to the Nazi Party, von Braun was readily adopted by the Americans, largely because of his skills as a rocket scientist. In 1975 he was awarded the National Medal of Science. Von Braun died in 1977 aged 65, from pancreatic cancer, leaving behind his wife Marie Luise (married 1947), two daughters and a son.

Otto Skorzeny: 1908–75

Skorzeny was born in Vienna and joined the Austrian Nazi Party in 1931. He was known for being charismatic and was easily identified by the dramatic duelling scar on his cheek. A bit player in the 1938 Anschluss (when he prevented the Austrian president from being shot by local Nazis), he was already a member of the SA (Sturmabteilung) when he tried to join the Luftwaffe in 1939. Deemed too tall and too old (6ft 4in and aged 31), he instead joined Hitler’s bodyguard regiment, the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler. Skorzeny impressed his superiors not only with his design skills – he had been a civil engineer pre-war – but with his courage and skill in battles on the Eastern Front. In December 1942 he was hit by shrapnel in the back of the head, but refused all medical treatment aside from a few aspirins, a bandage and a glass of schnapps. The wound quickly worsened and he ended up being rushed to Vienna for treatment.

Skorzeny was most famous for his rescue of Mussolini and his part in putting down the rebellion caused by the July 1944 plot on Hitler’s life. In 1947 he was tried as a war criminal for ordering his men to dress in discarded American soldiers’ uniforms during the Battle of the Bulge. The trial descended into farce when former SOE (Special Operations Executive) agent Forest Yeo-Thomas told the court that he and other operatives had worn German uniform to get behind enemy lines. To convict Skorzeny would expose the Allies’ own agents to possible court proceedings. He escaped conviction, but was detained in an internment camp awaiting the decision of a denazification court. In 1948 Skorzeny escaped the camp and went into hiding. He was reported in various countries over the next few years, sometimes working for their intelligence agencies. He helped countless former SS men escape Germany.

He died from lung cancer in Madrid in 1975.

Wolf Hirth: 1900–59

Hirth was a renowned glider and sailplane designer; his brother Hellmuth founded the Hirth Aircraft Engine Manufacturing Company. Hirth was born in Stuttgart and took up gliding as a young man, gaining his licence in 1920. He lost a leg in a motorcycle accident in 1924, but continued to fly with a prosthetic leg. Hirth founded a company with Martin Schempp in 1935, officially becoming a partner in 1938. They manufactured gliders, their first design intended to rival the famous Grunau Baby. During the war the company made assembly parts for the Me 323 and Me 109, along with other aircraft. Immediately post-war the company had to switch to making furniture and wooden components for industry, only switching back to gliders in 1951. In 1956 Hirth was elected president of the German Aero-Club. Three years later he was flying an aerobatic glider when he suffered a heart attack. He died in the subsequent crash.

Heini Dittmar: 1911–60

Dittmar was inspired by his elder brother Edgar to begin gliding and took up an apprenticeship at the German Institute for Gliding (DFS). He went on to build his own glider, Kondor, which he used during the Rhön soaring competitions of 1932. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s he both worked with and competed against Hanna Reitsch. He had once been besotted with her, but after she spurned his advances he began to perceive her as a rival. Post-war, Dittmar continued to work as a test pilot. He died while testing a light aircraft of his own design in 1960, when the plane crashed.

Peter Riedel: 1905–98

Riedel had a troubled childhood; his father, a Lutheran pastor and a theology professor, suffered frequent bouts of mental illness and his mother committed suicide. He spent some of his childhood with his uncle. In 1920 Riedel attended one of the soaring competitions on the Wasserkuppe and took part in it in a home-built glider. From then on he always attended the competitions while also acting as a commercial pilot. In 1936 he began working for an American airline and was approached by the German Military Attaché and offered a post in Washington DC. Riedel gathered intelligence on the US and forwarded it to Germany.

When America entered the war, Riedel and other Germans were interned and ultimately deported back to Germany. Riedel’s American wife went with him. For a time he worked for Heinkel as an engineer, then he was offered a diplomatic posting in Sweden. Once on neutral territory he began to learn the truth about the Nazi regime and was horrified to think he was working for these people. He tried to strike a deal with the American OSS (Office of Strategic Services), but was denounced by a co-worker and recalled to Berlin. Knowing his fate would be brutal if he returned to his homeland, Riedel went into hiding and remained out of sight until the end of the war.

Post-war, Riedel was arrested as an illegal alien in Sweden. He managed to escape and fled to Venezuela, eventually being joined by his wife Helen. For a few years they lived and worked in Canada and South Africa, until settling in the US, where Riedel flew for TWA and Pan Am. After his retirement Riedel devoted his time to writing the definitive history of gliding in pre-war Germany and shortly before his death his biography was published.

Captain Eric Brown: 1919–2016

Former Royal Navy officer and test pilot Eric Brown was said to have flown more different types of aircraft than anyone else in history – 487, to be precise. He first flew as a boy with his father and developed a passion for aircraft. Attending the 1936 Olympics, he met the First World War ace Ernst Udet, who offered to take him up in a plane. Brown eagerly accepted and during their flight Udet told him he must learn to fly. Brown was in Germany just before the war and was arrested by the SS at the outbreak of hostilities, though fortunately he was merely escorted to the Swedish border. Back in the UK, he joined the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve as a Fleet Air Arm pilot.

He served on the first escort carrier, HMS Audacity, before spending time as a test pilot. In 1943 he flew with the Royal Canadian Air Force, as well as with Fighter Command, before returning to test work. After the war he was employed testing captured German planes, including the infamous Me 163, to gain vital knowledge. He was able to fly a captured Fw 190 and gave his opinion:

The stalling speed of the Fw 190A-4 in clear configuration was 127mph and the stall came suddenly and without warning, the port wing dropping so violently that the aircraft almost inverted itself. In fact, if the German fighter was pulled in a g-stall in a tight turn, it would flick out on to the opposite bank and an incipient spin was the inevitable outcome if the pilot did not have his wits about him.

With his good grasp of the German language, he was also useful for interviewing German pilots such as Hanna Reitsch.

During the Korean War, Brown was seconded as an Exchange Officer to the United States Naval Test Pilot School and flew a variety of US aircraft. In 1957 he returned to Germany as Chief of British Naval Mission to Germany with the remit of re-establishing German naval flying, separate from the Luftwaffe (under which it had fallen during the Nazi years). He retired from the navy in 1970.

Brown wrote several books on aviation through the years, as well as numerous articles, and was considered one of the best authorities for the comparison of British and German wartime aircraft. He died in 2016, aged 97.

Mathias Wieman: 1902–69

Though Wieman wanted to become an aircraft designer as a young man, he found himself instead pursuing an acting career. He started on stage in the 1920s as a member of the Holtorf-Truppe theatre group, working alongside other well-known German actors, including Marlene Dietrich. Towards the end of the 1920s he moved into silent movies and was most active in the 1930s, performing in The Man without a Name, Queen of Atlantis, The Countess of Monte Cristo and The Rider of the White Horse.

During the war Wieman fell out of favour with the Nazi regime, with Goebbels in particular, which greatly reduced his ability to land acting roles. Though he did star in some films, his glory days were past. After the 1944 attempt on Hitler’s life, he and his wife helped the family of one of the failed plotters.

Post-war, Wieman found more work, largely in support roles, but also producing LPs of classic stories accompanied by orchestral music. He moved to Switzerland with his wife, where he died in 1969 from lung cancer.

Hugh Trevor-Roper: 1914–2003

English historian and professor of Modern History at Oxford, Hugh Trevor-Roper was born in Northumberland and studied history at Oxford. He is most famous for his bestselling book The Last Days of Hitler, which was much inspired by his work as an intelligence officer and designed to refute the rumours circulating that Hitler had escaped death in the bunker.

During the war Trevor-Roper served as an officer in the Radio Security Service of the Secret Intelligence Service, and in the interception of messages from the German intelligence service, the Abwehr. Trevor-Roper held a low opinion of many of his pre-war commissioned colleagues, but felt those agents employed after 1939 were of much better calibre.

Though not his first book, The Last Days of Hitler made his name as a top-rate historian. The book was internationally acclaimed (though for a long time it could not be sold legally in Russia) and even earned him a death threat. His lively, humorous and intelligent style made the book something of a historical classic.

Trevor-Roper was not opposed to criticising other historians or offering alternative opinions on history, particularly such subjects as the English Civil War and the origins of the Second World War. He successfully discredited the work of Sir Edmund Backhouse on Chinese history, causing the history of China as known in the West to be heavily revised. More controversially, he stated that Africa did not have a history prior to the Europeans, as there was nothing but darkness in terms of documentation before the arrival of the latter. This has caused great debate as to what actually constitutes ‘history’ in societies without a literary tradition.

In 1983 Trevor-Roper was notoriously involved in authenticating ‘Hitler’s Diaries’, later shown to be fakes. Though this led to many jokes in the press, it did not ruin his academic career, and he continued to write and publish. Trevor-Roper died of cancer in 2003. Five previously unpublished books and collections were issued posthumously.

Hans Baur: 1897–1993

Hans Baur was born in Bavaria and flew during the First World War. He joined the Nazi Party in 1926 and first flew Hitler in 1932 during the general elections. Hitler felt confident in Baur’s hands, especially as he helped him to avoid airsickness, and wanted to be flown by Baur exclusively. Baur was given the rank of colonel and sent to command Hitler’s personal squadron. In 1934 he was promoted to head of the newly formed Regierungsstaffel and was charged with organising flights for Hitler’s cabinet members and generals. He had eight planes under his command, but Hitler always flew in his personal plane with the tail number D-2600.

Baur became a friend of Hitler, able to talk to him freely and even offer advice. Though Baur refused to be converted to vegetarianism, Hitler invited him to the Reich Chancellery for his favourite meal of pork and dumplings on his fortieth birthday. Hitler was also best man at Baur’s marriage to his second wife. In 1939 Baur persuaded Hitler to change his personal plane to a modified Focke-Wulf Condor, but the number D-2600 was retained.

In 1944 Baur was promoted to major-general, and in 1945 to lieutenant general. He was with Hitler in the bunker and had devised an escape plan for the Führer, which Hitler refused. Baur was not present at Hitler’s suicide, but witnessed the bodies being burned. He then attempted to flee Berlin with others, but was shot in the leg and captured by the Russians. He spent ten years in Soviet captivity, ultimately losing his injured leg and enduring torture, starvation and interrogation. For many years the Soviets wanted to know where he had helped Hitler escape to, much to Baur’s frustration. He finally returned to West Germany in 1957 and started work on a book about his experiences during his time with Hitler. His second wife had died during his imprisonment; he went on to marry a third time.

Baur managed to skirt most of the controversy that affected other survivors of the Third Reich, possibly because he was absent for so long from his home country. He continued to live in Bavaria, where he died in 1993.

Robert Ritter von Greim: 1892–1945

Son of a police captain, von Greim joined the Imperial German Army in 1911 before transferring to the German Air Service in 1915. Two months later, he scored his first victory and went on to fly over the Somme. He ended the war with twenty-eight victories and had earned himself the title of Knight (Ritter). Between the wars, von Greim trained in law and spent time teaching flying in China, before joining the Nazi Party and participating in the 1923 putsch. In 1933 he was asked by Göring to help rebuild the German Air Force and in 1938 he assumed command of the Luftwaffe department of research.

Von Greim was involved in the invasion of Poland, the invasion of Norway, the Battle of Britain and Operation Barbarossa. In 1942 his only son was listed as missing and thought dead. In fact, he had been shot down by a Spitfire and spent the rest of the war a POW in the US.

Von Greim committed suicide in 1945 rather than be used by the Americans as a witness against other Nazis at the Nuremburg trials.

Jawaharlal Nehru: 1889–1964

Nehru was the son of a wealthy barrister who was also a key figure in the struggle for Indian independence. He was sent to study at Trinity College, Cambridge in 1907 and spent a great deal of his spare time studying politics. He returned to India in 1912 intending to settle down as a barrister, but the rising tensions in India and the continuing struggle for independence distracted him and he was soon involved in the movement.

The First World War drew mixed feelings from Nehru. His comrades were celebrating Britain’s fall, but he found it hard to side with the Germans. He ended up volunteering for the St John’s Ambulance. Nehru was now known for his political motivations and spent much of the next few years in and out of prison. He also spent a great deal of time with Gandhi.

During the Second World War he had again mixed feelings, but initially backed the British. When continuing protests at British rule in India were ignored, he started to feel less sympathetic. Though not impeding the war effort, Nehru and Gandhi did not help it with their displays of civil disobedience. Strains were placed on their friendship as the latter was adamantly against compromise with the British, even when Japan was threatening India’s borders. Nehru was less inclined to go against the Allies, but chose to side with Gandhi. India had become very divided and internal disputes were common, and would affect politics in the country for years to come.

Post-war, the British withdrew from parts of the subcontinent and Nehru became Prime Minister of India. Gandhi was assassinated shortly after. Nehru was a good political leader who promoted peace, but the many tensions within India meant his life was also endangered on more than one occasion. He survived these attempts, but the toll of power aged him and ravaged his health. Nehru died of a heart attack in 1964.

Indira Gandhi née Nehru: 1917–84

Indira had an unhappy childhood with her mother often ill and her father in prison. The only child of the future Indian prime minister, she retained the family fascination for learning and eventually studied history at Oxford University. She was plagued by ill health and was being treated in Switzerland in 1940 when the dangerous encroachments on Europe by the Nazis caused her to retreat to India.

Indira married Feroze Gandhi and in the 1950s acted as her father’s personal assistant. After his death she initially turned down the role of prime minister, but later accepted in 1966. India was still riven by internal tensions, and Indira had to battle these while raising two sons and enduring the criticism of US president Richard Nixon. Everything came to a head in 1977, when Indira was arrested and put on trial for allegedly plotting to kill all the opposition leaders who were at that time in prison. The trial backfired on her accusers and she gained a great deal of sympathy from the Indian people.

She was back in power in 1984 when she was shot by two of her own bodyguards just before she was due to give an interview to British actor Peter Ustinov. She died several hours later having been riddled with thirty bullets.

Kwame Nkrumah: 1909–72

Born on the Gold Coast, Nkrumah had trained and worked as a teacher before sailing to England and subsequently America to study. He read books on politics and became fascinated by Marxism and communism.

Nkrumah returned to Africa in 1947 and sought the independence of his country. The British withdrew from the Gold Coast, now Ghana, in 1951 leaving Nkrumah in charge. As president, Nkrumah had positive and negative points, the latter outweighing the former and he was regularly vilified in the British press. He became increasingly despotic and paranoid until a military coup was effected in 1966, while he was on a trip abroad. Persuaded of the futility of returning to Ghana, Nkrumah lived out his final years in exile writing books on his ideology and ousting from power.

He died of skin cancer in 1972, and is still remembered fondly by some in Africa. In 2000 he was voted Africa’s man of the millennium and in 2009 a Founders’ Day was created as a statutory holiday to commemorate his birth.

1

BORN TO FLY

Hanna Reitsch will fly the helicopter! screamed every poster in Berlin as the International Automobile Exhibition welcomed guests and journalists to the Deutschlandhalle. Within the large hall a petite woman with swept-back dark hair sat inside a machine that was to make history. No one had flown a helicopter like this before; in fact, no one had flown a viable helicopter before. This was a true first and Hanna realised the glory and responsibility placed upon her to fly the machine safely within a confined space.

There was little time to note the circus performers dressed in colourful garb and practising their somersaults and tricks on the side lines, nor the way the hall had been decked out to look like an African village as Hanna settled herself in the helicopter. With her slightly prominent chin, bulbous nose and hair hidden by a flying cap, few probably realised the person about to perform a miracle was a woman. Indeed, Hanna had only been due to fly on the first night, until her fellow male pilot had accidentally upset Herr Göring. In any case, no one was really looking; the real interest was not the pilot but the strange machine with double propellers facing into the air, giving the hybrid appearance of an aeroplane crossed with an ordinary household fan.

Hanna had practised for hours for this moment. The controls were sensitive and awkward, very little was needed to move the helicopter in a given direction and that was a danger: a slight miscalculation and Hanna could sweep into the audience, decapitating and maiming dozens in the process. The skill required made her tense, it also irritated her that this gargantuan feat was being performed as part of a spectacle for a mildly curious crowd. But if Germany wished to prove it was the first to build a successful helicopter, then this was how it had to be done. No one would take it seriously otherwise.

Hanna rose slowly, the propellers kicking up the sand and dirt on the floor and blowing off people’s hats. She climbed to a safe height, eye-level with the upper spectators, concentrating solely on the finely balanced controls, her brow lined with effort. Carefully she edged the machine forward, then gently turned. The helicopter moved with grace, belying the intense strain placed on the pilot to keep it steady. Moving back across the hall for one last turn, Hanna began her descent with relief. Another performance over, another crowd going home uninjured and the helicopter had demonstrated itself perfectly.

By now Hanna knew her display would not bring a standing ovation. The crowd was curious, but soon bored with the helicopter. What did it do but hover? How could that compare with the swooping aeroplanes they had seen before? Or the fast cars they had come to observe? The helicopter was an anti-climax, rather dull in fact: few really understood its potential at that moment.

But Hanna climbed out of her machine beaming her wide, enthusiastic smile. Never happier than when in the air, she was rightly proud of her achievements and those of Germany. She was elated to be standing on the verge of a new era in which Germany would prove itself a nation of inventors, engineers and geniuses. In February 1938, in the circus atmosphere of the Deutschlandhalle, anything seemed possible. The future looked full of hope. How little Hanna knew. How soon would this world of wonder plunge into war, taking her, the helicopter and the German flying community down a path of self-destruction from which Hanna would never recover. She beamed at the audience, and dreamed.

On a stormy night in March 1912, two years before Germany marched itself into the First World War, a screaming Hanna was brought into the world in Hirschberg, Silesia. Emy Reitsch stared at the scrawny bundle in her arms. On other dark nights she had had pangs of foreboding that she would not survive giving birth to another child, but here she was with her new daughter in her arms, alive and well. But that foreboding would always linger with her and project itself onto Hanna – Hanna was now the one who was always worried about and deemed fragile. Hanna was the one Emy would dread dying, as if this tiny baby were as delicate as glass. In contrast, Hanna would throw herself into more and more dangerous situations, as if defying over and over again that strange prediction of her mother.

Hanna was born into a reasonably well-off family. Her father was an eye doctor, her mother the daughter of a widowed Austrian aristocrat. Hanna was only the second child, her brother Kurt was 2 at the time of her birth. She would eventually be followed by a sister, Heidi.

Hirschberg was a beautiful city. Situated in a valley and almost entirely surrounded by mountains, Hirschberg had existed since 1108 and had a population of around 20,000 at the time of Hanna’s birth. The grand C.K. Norwid Theatre with its golden towers had opened ceremoniously in 1904 and the National History Museum opened to the public in 1909. A tram network opened in 1897 was already an integral part of city life by 1912. One thing in particular would come to delight Hanna: the natural heights around Hirschberg provided ideal opportunities for gliding, not to mention hiking, a popular pursuit of the Reitsch family. From a religious perspective, the city had a sixteenth-century chapel and a fifteenth-century basilica. Emy Reitsch had Catholic roots, but her husband was Protestant and she would raise her daughter on a mixture of the two, endowing Hanna with a complicated spiritual outlook.

The Reitsch family viewed themselves as German, or technically Prussian, with a deeply patriotic connection to Berlin. But Hirschberg was originally Polish, and there were still many among the population who felt more closely connected to Poland than Germany. The tensions between the two states did not make for easy living, but a form of harmony existed, even if it was fragile.

The problem was that Silesia had a complex history; originally part of Poland, it had become part of the Habsburg monarchy’s territory in the sixteenth century, effectively making it Austrian, though parts remained in Polish hands. With the renunciation of King Ferdinand I in 1538, Silesia had become part of Brandenburg. All these minor border changes paled in comparison with the upheaval caused by Frederick the Great of Prussia in 1742 when he invaded and took control of most of Silesia.

His interest was unsurprising; Silesia had thriving iron ore and coal mining industries. State-driven incentives, including the first modern blast furnace in a German ironworks in 1753, helped industry to flourish. Incentives for migrant workers encouraged them to join Silesia’s linen industry, which expanded rapidly under the protection of beneficial tariffs and import bans.

Invading Silesia itself had proved remarkably easy for Frederick (as it would almost 200 years later, when Hitler chose to invade the parts of Silesia that had fallen into Polish hands after the First World War). A long thumb-shaped piece of territory, with the River Oder running its length, starting in the mountains of Upper Silesia and finishing in the sea at Stettin, bisecting Brandenburg along the way, Silesia was an awkward piece of land sandwiched between various rivals. Poland sat on one side, while on the other was the kingdom of Saxony. The Saxon Elector, Frederick Augustus II, was doubling as King of Poland, so there was a natural incentive to absorb the nuisance expanse of Silesia into his kingdom.

Frederick the Great got there first, in a move some thought rash and impulsive. Whatever the case, Silesia officially became a part of Prussia. In 1871 the Prussian kingdom became part of the German Empire and Prussian leadership was supplanted by the new German emperor.

All this jostling of the state naturally tended to give its occupants a complex view of their origins and loyalties. Silesia was populated by a mix of Poles, Czechs, Germans, Prussians and those who considered themselves natural-born Silesians, not to mention the many immigrants who had been attracted to Silesia by its various thriving industries. Into this complicated historical blend of cultures Hanna Reitsch was born.

When Hanna was 6 the First World War ended and Silesia lurched into a new period of uncertainty. First there was debate within the German Republic as to whether Prussia should continue to exist at all. There was talk of boundaries being dissolved and Prussian influence being destroyed. In the end Prussia survived, though its powers were severely curtailed. Meanwhile, Poland was arguing that Upper Silesia should become part of the Second Polish Republic and in 1921 this is exactly what happened. What remained of the Prussian province of Silesia was redefined as Lower and Upper Silesia, while the small portion of territory termed Austrian Silesia, which had eluded Frederick the Great, was given to Czechoslovakia.

This was a strange time to be living in Silesia, let alone Prussia. That the Reitsch family were able to retain a strong sense of identity and a patriotic link to Germany is remarkable in itself, but the unpleasant annexing of different parts of their state, though they were unaffected, remained a lingering anxiety in their consciousness.

For Hanna, childhood continued as it had always done; she went to school, where she talked too much and was known for her larger-than-life presence and exuberance. At home she learned music and spent time with her mother, forging the close bond they retained until the latter’s death. But in the wider German world trouble was rife. Berlin, once ruled by the Prussians, was in turmoil. No one was certain who was in control and there were plenty of opportunists ready to fill the gap. On 7 January 1919 leftists took over a railway administration headquarters and government troops swooped in with small arms and machine guns. While the battled raged a train full of commuters calmly travelled on an elevated viaduct over the fighting, apparently oblivious to the chaos. A witness, Harry Kessel, remarked, ‘The screaming is continuous, the whole of Berlin is a bubbling witches’ cauldron where forces and ideas are stirred up together.’

Revenge killings began in earnest. The Communist leaders Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht were arrested and beaten to death by members of a cavalry guards division. Fuelled by violent hatred, the Communists launched into all-out civil war: 15,000 armed Communists and supporters took control of Berlin’s police stations and rail terminals; 40,000 government and Freikorps troops had to be called in and machine guns, field artillery, mortars, flame-throwers and even aeroplanes, which had only months before been pounding Belgium and France, were now turned on the capital. When the rebellion came to an end on 16 March the dead numbered 1,200 and trust between the old leadership and the people had been destroyed forever.

Antisemitism in Prussia during the 1920s was as rife and virulent as anywhere else in Germany; in places it even seemed to go deeper. Branches of the German Church began spouting racist propaganda; in 1927 the Union for the German Church announced in one of its publications that Christ would ‘break the neck of the Jewish-satanic snake with his iron fist’. Hanna’s strong links with the Church through her mother would have brought her into contact with diverse views, including those of some Christian groups who believed that collections for mission work to the Jews should be stopped. At the General Synod of the Old Prussian Union in 1930 a vote was taken to exclude the mission to the Jews from official Church funding. The disheartened president of the Berlin mission wrote letters appealing to Church leaders to reconsider, noting his horror that so many clergymen had succumbed to antisemitism.

The attitudes of their superiors had to have an effect on the personal outlook of the ordinary churchgoers. Hanna was still a rather dreamy youth and the religious controversy around her failed to penetrate her consciousness deeply, but it was there nonetheless and she could hardly have been ignorant of the growing resentment towards the Jews, as she later claimed.

For Hanna, life revolved around school and the desire to fly. All she talked about was taking to the air. After the war strict limitations had been placed on Germany’s flying capabilities. Powered flight was forbidden. To fill the void, aviation enthusiasts took to gliding, soon turning Germany into the greatest gliding nation. To Hanna gliding seemed everything. The mountains of Hirschberg offered the perfect place for soaring in the air and it was normal enough for Hanna to walk to school or catch a tram and see a glider swooping overhead like a bird. But such dreams were for boys, not girls. Girls got married and had children. Girls did not aspire.

But Hanna did, and when her father finally grew weary of her constant flying talk he extracted a promise – if Hanna said no more about flying then in two or three years, when she had finished school, her father would reward her with lessons at a gliding school in Grunau, not far from Hirschberg. Herr Reitsch hardly knew the error he had made. He imagined his daughter flighty, impulsive and unable to control herself. He did not recognise her iron will and determination, especially when it came to flying. Hanna kept her side of the promise, as torturous as it was for a naturally vocal child, and when she finally left school it was with her usual, enormous smile that she reminded her father of his promise.

It was now 1931. The rise of National Socialism was like a feverish virus infecting the German population. In 1928 the NSDAP (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei) had been nothing more than a chain-rattling splinter party with only 2.6 per cent of the vote. Two years later, with the unexpected dissolution of the Reichstag, it made a triumphant rise to 18.3 per cent; 810,000 Nazi voters in 1928 had turned into 6.4 million in 1930. National Socialism was now a big threat to the other political parties and Prussia was particularly uncomfortable at seeing such a controversial splinter group making the biggest gain of any political party in German history. Nazi apologists have made a case for National Socialism seeming very innocuous in its early days, fooling innocent, if gullible, citizens into voting for a party that would later turn out so evil. But this is whitewashing history; the Prussian authorities recognised the danger in 1930 and made it illegal for any Prussian civil servant to join the NSDAP. They considered the Nazi Party anti-constitutional and preparations were even made to have it banned altogether. As history tells us, this never happened.

Instead, the Nazi Party continued to gain popularity, as did its paramilitary branch, the SA – despite a ban on their activities. Across Silesia membership of the SA had gone from 17,500 in December 1931 to 34,500 in 1932. As sheltered a life as Hanna led, it would be impossible to avoid all signs of the conflict within Germany. It was akin to a small revolution. SA storm troopers, identifiable by their brown shirts, would rumble into the streets after dark and seek out Communists for a fight. Soon the police and the Reichsbanner (a half-forgotten republican militia) were absorbed into the fray and all-out brawls turned streets into battlefields, with residents finding evidence of the violence the next morning in the blood on the pavements, smashed windows and the odd lost knuckle-duster. Still, in 1931 Hanna was lost in her plans to fly.

The School of Gliding in Grunau would have done little to inspire a casual observer; there was a large hangar where the gliders were kept and a small wooden building that served as a canteen and shelter during bad weather. The rest was open ground. But for Hanna riding up on her bicycle, the scene was electric. ‘My heart was filled with joy,’ she later recalled.

The instructor at the school was Pit van Husen, a man who would later be remembered as the greatest of glider pilots. Van Husen was strict with his pupils, for good reason. Gliding looked simple, even safe, but it was far from it. Glider pilots did die when their flimsy craft were hurled into an unexpected storm or they misjudged a landing. Hanna rarely knew fear, however, and now she was on the practice field she would not be deterred by talk of accidents. Nor would she be upset by the unpleasant stares and comments made by her fellow, all-male, students. Hanna was not welcome. Her presence was resented and openly mocked. She was a petite 5ft 5in among the lean, tall Aryans who sidled around the airfield and she endured her fair share of snide remarks that a woman should know her place and stay in the kitchen. She later claimed that she ignored these comments, but evidence from other sources suggests she was more sensitive than she cared to admit. The sneers of her fellow students stung and they spurred her to become defiant and to be the first to truly fly.

Van Husen started his students slowly, first allowing them to learn to balance the glider on the ground while he held one wing-tip, then having them perform short slides on the ground. It was during one of these that Hanna decided enough was enough – she would show these obnoxious boys what she was made of! She had completed one slide and was restless. ‘Flying does not seem difficult,’ she thought to herself as she sat in the glider waiting for her last slide. ‘How would it be if I pulled back the stick just a fraction, without anyone noticing? Would the “crate” take me a yard or so up into the air?’

So the School of Grunau learned what the real Hanna was like. The daredevil within had taken over. The other students, wanting to spook this frail little girl who had infiltrated their class, hauled extra hard on the rope to give her a really fast slide. Hanna pulled back the stick just a few inches, and the combination sent the glider soaring. Hanna was jerked forward then back, for a moment she had no sense of what was happening, then she was looking up into blue sky. Hanna was flying!

From below a frantic Pit van Husen was shouting for her to come down. Hanna pushed the stick forward, the glider’s nose dropped steeply. She didn’t want to land, didn’t want to come out of her bubble, and she pulled the stick back and climbed again. But then something happened, the airspeed dropped, the glider lost whatever thermal it had found and she plunged downwards. There was a crash and Hanna found herself thrown from the plane with a gang of whooping boys tearing towards her. The glider was in one piece, so was Hanna, and she stood up and laughed at the oncoming students, who were delighted to see a woman fail so dramatically. Pit van Husen was another matter. ‘What did you think you were doing?’ the instructor was screaming at her, bellowing in his fury and fear. ‘You are a disobedient, undisciplined girl! I should never have allowed you here, you are completely unfit for flying!’

Hanna was cowed before the boys who were smirking and enjoying the performance. ‘As a punishment,’ continued van Husen, ‘you will be grounded for three days!’ Van Husen spun on his heel and stalked off. Several students followed, but a few remained. They were quietly impressed by Hanna’s daring. After all, she had been the first to fly. As they helped her haul the glider back to its start point, they gave her a new nickname – Stratosphere.

Hanna cycled home more dejected than she liked to admit to herself. Her foolhardiness had stripped her of her dream to fly before she had even begun. Now she would have to ensure she stayed on van Husen’s good side to avoid any further bans. It was to be far from the last time Hanna’s tendency to act before she thought landed her in trouble. What Hanna could not know as she rode home, arguing with herself that she was not completely unfit for flying, was that Pit van Husen was working on removing her from the course altogether. After Hanna had gone, he went to report to Grunau’s director, Wolf Hirth, and explained the full problem. A pioneer of gliding, Hirth was something of a god to his young students. He had a round, jovial face which, when he smiled, folded into happy creases and crumpled up his eyes. He was never happier than when flying, undeterred at having to wear both glasses and a prosthetic leg, having lost the original limb in a 1924 motorcycle accident. If anyone spotted him smoking they might have noted his unusual cigarette holder carved from the fibula of his lost leg.