Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

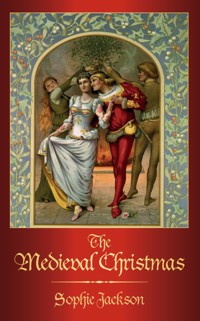

Medieval Christmas – roaring fires, Yule logs, boar's head on a platter and carols. So many of our best-loved traditions have their origins in the medieval period that it would be impossible to imagine the season without holly and ivy, carol singers calling from door to door and a general sense of celebration in the face of the harshest season. Sophie Jackson investigates the roots of the Christmas celebration in this beautifully illustrated book. She offers guidance for re-creating elements of the medieval Christmas at home, tips on decorations, instructions for playing medieval games and recipes for seasonal dishes. Fascinating facts about some of our most cherished customs, such as the nativity crib, are unearthed, as are some that are less well known – wassailing the apple trees, the ritual beating of children on 28 December and the appointment of a Lord of Misrule and a boy bishop. Lively and entertaining, this book illuminates the Medieval Christmas, showing how the traditions of the Middle Ages continue to delight us today.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 140

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Introduction

Chapter One Mummers, Mysteries and Miracles

Chapter Two Wild Boar and Wassail

Chapter Three Carols for the Common Man

Chapter Four Green Magic

Chapter Five Seasonal Saints

Chapter Six Smoking Fools and Boy Bishops

Chapter Seven St Nicholas, the Medieval Father Christmas

Bibliography

Plate Section

Copyright

Introduction

Welcome, sir Christëmas,

Welcome to us all, both more and less

Come near, Nowell!

From a carol attributed to Richard Smart, Rector of Plymtree, Devon, 1435–77

So entrenched is the view that the modern Christmas has its origins in Victorian times that it comes as a shock to realise that many of the customs we enjoy during the festive season date back to the Middle Ages or earlier. In the medieval period, people gave gifts, sang carols, decorated their homes, overindulged in seasonal food and drink and had their own Father Christmas, known then as St Nicholas. With its lengthy preparations and many saints’ days to mark, their Christmas season could last even longer than the modern holiday.

What is more, the medieval Christmas was quite literally a magical time. Most of the important Christmas dates began as powerful pagan celebrations that had been Christianised, although people could not give up the old customs completely and still cast their divination and fertility spells, now using the symbols of Christianity. Lost souls might wander the dark woods, demons might enter the house and cause chaos, but Christmas was the only time when Jesus Christ could also come into every home and drive away the pixies and sprites that threatened to mar the season’s joy. The old and the new merged. Saints were honoured in place of the old gods, the old magic became God’s miracles and pagan festivals assumed a new life as Christian feasts. The feast of Christmas, with its story of the birth of the Saviour who redeemed mankind from sin and death, was thus harmoniously woven into the fabric of an older tradition, albeit one that still lingered in memories of the past.

A French-influenced fool in his habit de fou with bells. (Bodleian Library, Oxford: MS Laud.lat 114, f. 71)

When we celebrate Christmas, we should remember those joyful medieval festivities. Just as now, so people then would have exchanged gifts, risen early on Christmas Day, gone to church and prepared a feast with roasted birds or boar, spiced alcoholic wassail and rich fruit cakes. They would have played games, often a shade more dangerous than their modern counterparts, danced and sung and looked forward to the year to come. The medieval Christmas was a lively, vibrant time, eagerly anticipated in the dark months of winter. There were few who did not try to mark it in some way, even the poorest, and incorporating their traditions can serve to enrich our own Christmases.

Chapter One

Mummers, Mysteries and Miracles

The History of Mystery and Miracle Plays

The medieval mystery and miracle plays performed at Christmas re-enacted Bible stories and were among some of the most popular entertainments of the Christmas season. They were probably based on an earlier form of religious theatre, the liturgical drama that first appeared in the tenth and eleventh centuries as a means of helping ordinary people learn biblical tales, consisting of very short plays in the vernacular as well as Latin, which gave the common man a chance to understand what was happening.

These early medieval plays were originally performed by monks, but problems soon arose with some of the subjects; for instance, the story of the Massacre of the Innocents posed the question of whether it was right for a monk to represent the evil King Herod. Was it even spiritually sound to portray such a vile act within the walls of a church? The liturgical dramas never went further than the original few short lines, but they served to open up a whole new dimension of entertainment. Secular performers had already started to develop new plays, so the atmosphere was ripe for the mystery and miracle plays to flourish.

As far as we know, the oldest such play was written by Abbot Geoffrey of St Albans in 1110. Taking St Katherine as its subject, it was performed in Dunstable, where the Abbot taught. In the years that followed, many mystery and miracle plays were created, and eventually the whole story of the Bible – from the Creation to Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection and, finally, Doomsday – was enacted.

The difference between the two types of play was that the mysteries described the stories of the Old and New Testaments, including those of Cain and Abel, Noah’s flood and the Nativity. The miracles, on the other hand, told of the lives of the saints. The miracle plays could be performed in conjunction with the mysteries or as separate short pieces, as was the case with the one about St Katharine.

Pageants

The mystery plays were gathered together in cycles, which related the whole of the Bible. The entire cycle was performed in one day, usually close to Christmas or around Easter, the two most important Christian dates in the church calendar. At Christmas time, they brought life to the dark nights of winter and helped celebrate the festival. The plays were originally performed in churchyards, and large groups of people would gather outside the church to watch. But the actors tended to get carried away, and the plays became coarser, ribald and in some parts lewd. In the thirteenth century, many of the clergy were no longer prepared to tolerate what they saw as a debasing of the scriptural message, and the plays moved out of the churchyards and into the streets.

The actors now had no stage, but that did not stop them. They constructed two-tier wagons called pageants that could be transported to a given place in the town or city, the two levels of the stage providing performance space, with the ground in front of the wagon forming a third stage. Each Bible story had its own scenery, and this was fixed to the wagon. In cities such as Chester and York, each city guild created a pageant and acted out one Bible story on its own wagon. Thus it was even more important for the plays to be staged on pageants so they could process through the streets, stopping at a designated place, performing their stories and then moving on so that the next wagon could take their place and its occupants perform their own plays.

Music enlivened the dark nights of winter, with bagpipes, recorder and drums among the instruments. (Bodleian Library, Oxford: MS Douce, 18, f. 113v)

The place where the wagons stopped often depended on who could pay the most for the privilege of having the actors perform outside their houses. The wealthier merchants and townspeople preferred to watch the plays from the comfort of their homes – and considering how long the cycle could last this is hardly surprising. In York, the plays started at four thirty in the morning and did not finish until dusk. Those who could not afford to purchase the privilege of having a performance outside their homes would have to stand in the streets and watch, a brave act in the middle of winter.

The Actors

In liturgical dramas, monks had acted out the Bible stories; in the mystery and miracle plays, secular players took the roles and performed on the pageants. Any group of people might come together to organise a play for Christmas, but in the cities the guilds took over the running of the performances. The large guilds could afford to put on bigger and grander shows because they taxed their members. This tax was used to cover the costs of scenery, costumes and, in some cases, the hiring of the actors, though in other guilds the members took the roles. Actors were paid for performing, though deductions were made for poor acting or forgetting lines.

Despite the guilds’ involvement in the plays, there was still a stigma attached to entertainers. Though some exceptions were known, most actors were considered the lowest level of society, little better than beggars, cripples or vagabonds. Though this attitude had softened somewhat by the thirteenth century, acting was not considered an honourable occupation, and despite having its own liturgical dramas, the church frowned upon it. Monks and members of the clergy were strictly forbidden to take part in any of the plays enacted in streets or houses during festivals. Those who were found doing so were punished.

Mummers would perform in the fashions of the day. These mummers wear long hoods like those in the Haxey Hood game (see Chapter 6). (Bodleian Library, Oxford: MS Bodleian 264, f. 129)

The actors were mainly amateurs but threw themselves into their parts. When Father Nicholas de Neuchâtel-en-Lorraine played Christ in Metz, France, in 1437, he almost died on the cross.

There was often little money, unless the guilds supplied the funds, and the players often performed in their everyday clothes. Such costumes as there were would most likely have been based on the fashions of the time, though some characters, such as God, would have required special robes and a mask. The modern York plays are performed in fourteenth-century costume to be in keeping with the original actors’ dress. The York Cycle is but one example of medieval mystery plays. In total, forty-eight plays were performed during the cycle, originally acted by different guilds. Imagine all these plays being performed one after another on huge wagons adorned with scenery and actors in fancy costume – it must have been an extraordinary sight and one that kept the audience enthralled the entire day. The pageant wagons were housed on Pageant Green, though they no longer are today. On a day near Christmas, the great wagons were drawn by horses away from the green and rumbled through the city, making twelve stops at each of which the actors performed their short plays.

Outside the cities, few would have known much about the elaborate mystery cycles unless they happened to have visited a place where they were being performed. For poorer villages and hamlets, another form of entertainment enlivened the dark winter. It was less expensive and did not require vast stages or a whole day to perform. This less grand form of acting had its own class of actors, the mummers, and was very different from the mystery plays of York and Chester.

Mumming

Mumming is an ancient form of street theatre. The practice began in Britain before the coming of Christianity and was a fertility rite marking the death of the summer during winter and its rebirth in the spring. The word ‘mumming’ or ‘mummers’ (meaning ‘the performers’) is controversial in origin. There are two possible explanations. It may derive from the German word Mumme, which means ‘mask’ or ‘masker’, suggesting the word did not come into use in England until after the Germanic tribes invaded in the fifth century and that before this the players would have had another name. The other theory is that the word comes from the Greek momme, meaning ‘frightening mask’ or ‘ogress’. Both names refer to the masks the mummers wore to disguise themselves during a performance. This disguise was important for it was believed that if a mummer were recognised, the magic of the ritual would be broken and might even prevent the sun from returning. In some places, it is still important that mummers are not recognised while performing their plays.

Because of the timing of the ancient ceremony in mid-winter, when the days were at their shortest and the sun’s rays weak, mumming has become associated with Christmas. The medieval mummers would start their performances around Halloween and continue through to Easter. The association with Christmas happened when Christianity reached Britain, and pagan ritual and practice were given new meanings that fitted into a Christian context and were assimilated into the new religion. So the popular ancient rituals of mumming that enacted the death of the sun and its rebirth in the spring were retained.

By the Middle Ages, mumming activities had already lost some of their original significance. People were no longer as afraid as their primitive ancestors had been that the sun would not return, though they still continued the old practices just to be certain. The mummers were turning into actors, their performances now as much for entertainment as to follow ancient ritual. The Anglo-Saxons might have used some of the mumming rituals as training for their warriors, but as the medieval period progressed, so gradually mumming became solely a Christmas entertainment, and its original purpose and meaning were obscured.

St George slaying the dragon, a common theme in mummers’ plays. (Bodleian Library, Oxford: MS Don. d.85, fol.130r)

Medieval Christianity brought new characters to the mummers’ plays. Of these, Beelzebub was the most common, and he frequents most modern versions of the old plays. There was also Father Christmas or, as he was sometimes known in medieval times, Old Man Winter, who would appear wielding a club and shouting – certainly not a Father Christmas we would recognise. The most important new character, one who transformed the part of the hero and altered the nature of some of the mumming, was St George. He came to fame after supposedly killing a dragon in Egypt around the third century, and his life was described in a book entitled Famous Historie of the Severn Champions of Christendom that included six other champions.

St George became a staple of medieval mumming plays, sometimes accompanied by his dragon, though this was a difficult and expensive prop to make; hence, the dragon became more symbolic, and his place was taken by other villains. After the crusades, this became the Turkish Knight.

St George was eventually replaced in later periods by Prince George or King George, but his Christian influence on the art of the mummers was not forgotten. In modern mumming, St George is beginning to reappear.

The Three Types of Mummers’ Plays

There are several different forms of mummers’ plays, but not all performers who went under the name of mummers actually acted. Some simply cavorted about the streets in animal masks, occasionally singing carols and often visiting houses to collect money or a drink of ale. These performers could be little more than beggars and sometimes troublemakers. The true mummers performed three types of mummers’ plays, which were the Hero/Combat, the Wooing Ceremony and the Sword Dance. All treat the themes of death and rebirth, each in a different way, and to understand the mummers it is necessary to understand the differences between their plays.

The Hero/Combat plays are the best known. The mummers stand in a circle in the middle of their audience and proceed to speak lines, which are rhymed. They start with the prologue, introducing the characters who are about to perform. (The main mummer, such as St George, may read this piece and step forward as he does so.) Though the actors usually form a circle, some of the plays contain directions for entrances and exits just as for a play performed on a stage in a theatre. In this case, as the introduction is spoken, the main characters join the speaker in readiness to perform. After the prologue, the hero often speaks, his speech usually making little sense other than to act as a challenge to his opponent, the villain. This villain can be any character – in the case of St George, it could be a symbolic dragon or the Turkish Knight.

The challenges result in a sword fight. This can be highly ritualised, like the Sword Dance Ceremony, but always ends in the death of one of the combatants, as often the hero as the villain. Then follows the lament, performed by either the hero or another character. The lamenter regrets the death of the combatant and calls urgently for a doctor to come and revive the fallen man. A quack doctor then appears and attempts to resuscitate the dead man in a scene that is comic and often forms the main part of the play. Before his cure is even carried out, the doctor recites a list of the diseases he has cured and the places he has been and in general blows his own trumpet in a long speech before he finally produces a bottle of medicine, which he gives to the corpse. Miraculously, the strange potion revives the fallen man. But this is not the end of the play. Occasionally, there is another fight, sometimes with different combatants, and if one dies he may not be revived as before. The play concludes with the arrival of superfluous characters who appear to have no real function in the plot but have nevertheless become a part of the ritual. Most common among these late arrivals is Beelzebub. He appears just in time for the ending of the play with a seasonal song.