Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

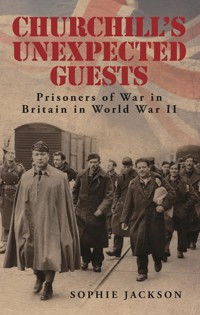

During World War II over 400,000 Germans and Italians were held in prison camps in Britain. These men played a vital part in the life of war-torn Britain, from working in the fields to repairing bomb-damaged homes. Yet despite the role they played, today it is almost forgotten that Britain once held PoWs. For those who worked, played or fell in love with the enemies in their midst, those times remain vivid. Whether they took tea on the lawn with Italians or invited a German for Christmas dinner, the PoWs were a large part of their lives. This book is the story of those men who were detained here as unexpected guests. It is about their lives within the camps and afterwards, when some chose to stay and others returned to a country that in parts had become a hell on earth.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 377

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CHURCHILL’S

UNEXPECTED

GUESTS

CHURCHILL’S

UNEXPECTED

GUESTS

Prisoners of War in Britain in World War II

SOPHIE JACKSON

First published 2010

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Sophie Jackson, 2010, 2013

The right of Sophie Jackson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9680 1

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

one

When the Fighting was Done

two

The German Guide Book

three

Safer Shores

four

Nazi Murder on British Soil

five

You Can Work If You Want

six

A Girl’s Gotta Do What a Girl’s Gotta Do …

seven

And Then There Was Peace

appendix

POW Camp Directory

Bibliography

one

WHEN THE FIGHTING WAS DONE

GENEVA CONVENTION

Any discussion on prisoners of the Second World War needs to begin with an understanding of the Geneva Convention, the twentieth-century document that formed the basis for how prisoners in Britain and to a degree in Germany were confined. Its limitations, however, opened it up for abuse and despite many prisoners believing it to be a legal document that must be upheld by their captors, it was in fact only a moral code. None of the rules laid out in the document had to be followed, only considered and interpreted as the captors saw fit.

For German troops in particular, the fact that the British and Americans upheld the Geneva Convention made being captured by them a far better option than being captured by the Russians, who had no intention of treating Nazi prisoners well. As part of the agreement, both Britain and America had to make provisions for a neutral country to visit the prisoners to ensure their well-being. Russia, on the other hand, could hide away their prisoners, abuse them and leave them to die without any other nation observing them.

The very first Convention had come about in the nineteenth century after the publication of A Memory of Solferino, written by Henry Dunant, a Swiss man who had helped tend to dying and wounded soldiers for three days and three nights after the battle of Solferino in 1859. The fight between the French and Austrians left 6,000 dead and 40,000 wounded. The French army’s medical teams were overwhelmed; they had more veterinarians than doctors. The harrowing aftermath of the battle that Henry Dunant recorded in his book inspired Europe to create some form of document that would protect those wounded in battle.

The first meeting to discuss the Convention occurred in 1864, when sixteen nations came together in Switzerland and twelve agreed to sign the first Geneva Convention and created the Red Cross flag (a reversed version of the Swiss flag).

One of the most significant factors of the treaty was that it established the neutral status of military medical personnel. Further treaties discussed at the peace conferences held at The Hague were established before the Great War, and during that conflict, neutral countries such as Switzerland took informal responsibility for ensuring prisoners of war were treated well. This included visiting camps and hearing prisoners’ complaints.

However, the main provision of the Convention was to deal with wounded soldiers and this left deficiencies in the guidelines for the treatment of captured prisoners. In 1929 the nations came together again and signed the second version of the Convention. Included in those nations that agreed to follow the Convention was Japan. The Soviet Union, due to spending the 1920s isolated from the international community, never signed the treaty.

This proved disastrous for German soldiers captured by the Russians; they were starved, brutalised and often left to die in the freezing Eastern European winters. For Russians in German camps the situation was little better as the Germans decided to ignore the Convention in relation to their Eastern European prisoners, while following it in regards to their British, French and American prisoners.

The Convention set out a number of points that a ‘hostile government’ should follow in relation to its captives, including:

They [POWs] shall at all times be humanely treated and protected, particularly against acts of violence, from insults and from public curiosity. Measures of reprisal against them are forbidden.

No pressure shall be exercised on prisoners to obtain information regarding the situation in their armed forces or their country. Prisoners who refuse to reply may not be threatened, insulted, or exposed to unpleasantness or disadvantages of any kind whatsoever.

Their identity tokens, badges of rank, decorations and articles of value may not be taken from prisoners.

Belligerents are required to notify each other of all captures of prisoners as soon as possible …

Work done by prisoners of war shall have no direct connection with the operations of the war. In particular, it is forbidden to employ prisoners in the manufacture or transport of arms or munitions of any kind, or on the transport of material destined for combatant units.1

Much of a nation’s compliance with the regulations was due to reciprocity. Britain held strictly to the Convention, even after the war ended, in relation to its German prisoners for fear that if they did not something untoward might happen to British prisoners in German hands.

But like all agreements, the way the rules were interpreted and followed depended on individual camp conditions and their commandants. Britain also found it difficult to treat its prisoners equally in all its dominions, and its camps in France and Belgium were particularly notorious. In addition, the government struggled to gain uniformity between British and American camps, some German POWs having been sent to the United States.

The German prisoners themselves tended to see the Geneva Convention as a law that could be enforced by the ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross) and punishments were imposed for infringements. In truth, the Convention had no standing in international law; the regulations were principles which the nations that had signed were only morally obliged to hold to.

For the most part, sticking to the Convention’s principles as rigidly as Britain did was due less to national conscience than to the real fear of reprisals against British POWs. An early example of how reprisals could grow and cause international and national concern happened in October 1942.

On 7 October the German High Command announced that it would be chaining the hands of all British soldiers captured in Dieppe because ‘British troops had tied the hands of German soldiers in the raids on Dieppe and Sark’.2

The British government’s response was to declare that if British soldiers were not freed from their chains by 10 October, an equal number of German prisoners would be shackled. The German High Command immediately replied by ordering that three times the number of British prisoners should be placed in chains. They refused to release the men until Britain agreed that never again would they tie the hands of Germans captured in raids.

The Swiss government, trying to act as a neutral mediator, attempted to break the deadlock of ‘German reprisals and British counter-reprisals’. They appealed to the nations involved:

In conviction [sic] that it was with reluctance that Germany, as with Britain and Canada, was led to shackle prisoners of war, Switzerland, the protecting power for German interests in the British Empire and for British interests in Germany, has suggested simultaneously to the interested governments a date on which those prisoners should be freed from their shackles.3

Earlier on the day that the Swiss gave their appeal, the Prime Minister had been questioned on the subject, particularly about whether Canada had been consulted before German prisoners in their country were ordered to be shackled by the British. He responded: ‘On account of urgency it was not possible to consult any of the Dominion governments upon the counter-measures to the German shacklings which were deemed necessary in October by the government.’4

After the appeal, the Foreign Office announced that all German prisoners in British hands would be unshackled as of 12 December 1942. The Canadians issued a similar statement that German prisoners would be untied without delay. This did not have the desired effect in Germany, where British POWs remained shackled until December 1943.

The official reports compiled after the war noted that it was not just the tying of German hands that had caused reprisals, but the discovery of a number of German bodies riddled with bullets lying at the bottom of the cliffs at Dieppe. In the end, it was not diplomacy that ended the stalemate but a shortage of camp guards, who became slack in the shackling of their British prisoners. The prisoners’ hands were meant to be tied in the morning and untied at night, but eventually the guards merely gave the shackles to the POWs and ordered them to tie their own hands. Though punishments were still inflicted for failing to wear the chains, very often the camp staff simply ignored the infringements.5

PRISONER NATIONALITIES

For the most part, when people recall the POWs held in Britain during the war they usually remember them as either Italian or German. Indeed, most official documents would give the impression that only men from these two nations were ever captured. Yet the range of nationalities of the men held in the UK was in fact far greater than that. In 1947 8,000 Ukrainian prisoners of war were brought to Britain from Italy. Once here volunteers were selected for agricultural work and for long-term residency in the UK.6

The Germans had conscripted a number of soldiers from their neighbouring countries along with any they conquered. During one interrogation the seaman being questioned revealed he came from Vienna in Austria, but considered himself a German. He had been a labour conscript sent to Germany in 1939 and from there he was eventually drafted into a U-boat school at Wilhelmshaven.

As the war progressed, the Germans made a habit of encouraging their prisoners to join the military. Another POW who found himself housed in a camp in Suffolk was Czechoslovakian and had been effectively press-ganged into the German army.

In the latter stages of the conflict the Germans even tried to persuade British POWs to re-enlist under the Nazi flag. Similar tactics were used on Russian prisoners to greater effect.

Russia and Germany were bitter enemies; the Nazi regime viewed the Russians as little better than savage animals. German soldiers feared capture by the Russians knowing the horrors they would endure, and the situation was no better for any Russian who fell into Nazi hands.

British POWs were often held in camps next door to Russian prisoners with little more than a barbed-wire fence separating them. Yet the conditions either side of the wire could not have been more different. While the Germans followed the Geneva Convention in regards to their British captives, they saw no reason to treat the Russian enemy similarly. The Russians were starved and brutalised. If any tried to escape they were shot immediately. There are stories of British POWs feeling so sorry for the starving Russians that they would try to throw some of their rations to them, but when a Russian attempted to retrieve the food they were shot dead by a guard.

Unsurprisingly, when faced with such horrors and knowing that their leader, Stalin, had effectively washed his hands of any man who was captured – considering them lost in action – the Russians were prepared to accept the Nazi offer to join the German army.

To the British, the nationality of their prisoners was not as great a concern as their political attitudes. German prisoners in particular were classified and housed according to their beliefs. Prisoners were screened upon entering Britain and then placed into one of four groups: Grade A (white) were considered anti-Nazi; Grade B (grey) had less clear feelings and were considered not as reliable as the ‘whites’; Grade C (black) had probable Nazi leanings; Grade C+ (also black) were deemed ardent Nazis. ‘Blacks’ were usually housed in special camps, often situated in remote areas where escape was harder.

Grading was essential not only for security, but also prisoner welfare. While most camps had a mixture of ‘white’, ‘grey’ and ‘black’, some camps were predominate in one grade of prisoners. On occasion a Grade A (white) prisoner was placed into a Grade C+ (black) camp; in such situations the results were often assaults on the ‘white’ anti-Nazi, occasionally with fatal consequences.

Grade C+ were not supposed to leave base camps and they were not to join working parties except under the supervision of the Director of Labour. If a C+ prisoner was discovered to have been accidentally sent to a working camp then he was to be immediately transferred away.

GERMAN DESERTERS

It is sometimes easy to forget that not all German soldiers believed in Hitler and the Nazi regime or wanted to fight Britain. Some made active attempts to be captured and then reveal useful information to the British; there were even those who, after being taken prisoner, asked to join the British army.

One such man was Uffz Franke, who had spent a year in a German prison from March 1941 after ‘expressing views prejudicial to the regime’. Despite his anti-Nazi feelings he was sent with a Panzer division to Africa in 1942 where he arranged to be captured by the British. Franke had anti-German feelings and when flown back to the UK he applied to join the British army. The authorities considered using him as a stool pigeon, a line of work that required a good deal of courage as the risks if exposed could prove fatal. Franke was turned down for the role as he was considered ‘lifeless and timid’.

Deserters, however, were not always the most reliable of sources for information. Many were keen rather than useful and had gathered information randomly, usually without understanding the context, to try and be helpful to their captors. The interrogation services regularly double-checked information and reported its accuracy, often with disappointing results.

THE ‘DISEASED’ ITALIANS

Among the earliest POWs to arrive in Britain were large numbers of Italians; many had been captured in the Near East where they were all too willing to surrender to the British troops. Once they were captured it was necessary to set up camps in Britain and transport the new captives there.

Amid the many concerns about finding a suitable location for a prison camp, one was primary in certain people’s minds. The Italians were being shipped from a location rife with disease, many were already suffering from some form of illness, and it was vital to the War Office to protect the health of the British public.

In a letter written by Dr P.G. Stock on 17 June 1941, he reports:

From the information in his possession Brig. Richardson anticipated that malaria, dysentery, typhoid fever and pediculosis had been rife amongst the prisoners. He said that the army authorities would provide the necessary hospital accommodation at the transit camps and would see that the men were disinfected: in addition he was considering having them all inoculated against typhoid fever, but feared that a number might be carriers of malaria, dysentery and typhoid.7

Three thousand Italians were due to arrive on 8 July of that year, the first of a proposed 50,000 Italian prisoners that were being shipped to Britain in the hope that many could help fill the labour shortage in the country. Suddenly the authorities were gripped with unexpected panic. They had sick men heading their way carrying potentially lethal diseases to an unsuspecting population.

The men were to be initially housed at two transit camps, one in Lodge Moor, Sheffield, the other in Prees Heath, Shropshire, but where the men were to go next was still in debate. A telegram was forwarded to the Ministry of Health discussing the problem.

In a letter dated 24 June 1941 it was stated:

The Minister [of Health] apprehends that certain infectious diseases may be prevalent amongst these Italian Prisoners of War and is anxious that all possible steps are taken to prevent any spread of such diseases … the minister is particularly concerned to ensure that precautions are taken in districts to which these prisoners of war may be sent to work as labourers … I am to add that the risk of the spread of malaria is greater in some parts of the country than others, and the ministry would be prepared to furnish you with information on this point if it is agreed that steps would then be taken to avoid … sending any Italian prisoners of war who may be carriers of malaria to a district where there is the most risk of spreading the disease.8

Eventually a list of the locations for the Italian POW camps was announced:

The Labour Camps for the first 3,000 Italian prisoners of war (for Agriculture) due to arrive about the 8th July, 1941, are located as follows:-

(a) Farncombe Down. 1 mile east of Baydon, Wilts.

(b) Melton Mowbray (Leicestershire).

(c) Ledbury. ¾ mile south (Herefordshire).

(d) Doddington. 4 miles south of March (Cambridge).

(e) Rugby. 2 ½ miles south (Warwickshire).

(f) Anglesea. Glan Morfa. 3 miles south of Llangefni.

(g) Baldock-Royston area. (Hertfordshire).9

Almost immediately concerns were raised about the choice of certain locations. Even with health screening at the transit camps, involving the taking of in-depth medical histories and giving inoculations, there was still a fear that a disease-carrier might be unintentionally sent to the wrong location. The greatest fear was the spread of malaria which is contracted from the bite of an infected mosquito. If a mosquito were to bite an Italian who was a carrier of malaria, it would then drink infected blood and potentially pass this on to anyone living in the vicinity.

Further reports of the potential dangers were hastily drawn up. Dr P.G. Stock wrote:

Anopheline mosquitoes are found throughout England and Wales, but fortunately our experience shows that it is only one species, namely Anopheles Maculipennis, which is concerned in the spread of malaria. Moreover, it is only one variety of this species which is the real danger … (variety Atroparvus). This variety is only found in sufficient numbers to constitute a real danger … along the south coast of England, east of Wareham in Dorset and up the east coast as far north as the River Humber. Included in this area is the valley and the estuary of the Thames, the Isle of Grain, the Isle of Sheppey and places such as Harwich, Dovercourt, Walton-on-the-Naze, Ipswich, Great Yarmouth and the country bordering the Wash, namely parts of Norfolk, the Isle of Ely and Lincolnshire.

… From the War Office letter of the 28th June, it is noted that a certain number of Italian prisoners of war are to be sent to Doddington, four miles south of March in the Isle of Ely, and unless these men can be diverted elsewhere special precautions should be taken in the district. The matter is of importance as we are now in the most dangerous period of the year for the spread of malaria.

This news provoked consternation among the concerned parties and, writing to a Mr Shute of the Malaria Laboratory, Horton hospital, Epsom, Dr P.G. Stock was determined to clarify the risks: ‘The War Office, however, want to know how far inland from the coast the danger zone exists. I believe most of the coastal belt is a reserved area for war purposes and the question does arise whether the area reserved for war purposes is sufficient for malaria purposes.’10

Mr Shute’s response was tinged with the difficulty of the situation:

I would suggest that the War Office be told that the danger zone is anywhere in England where stagnant water is brackish.

We cannot give any hard and fast rules about this because in some areas brackish water may extend some miles inland, while in others it may not exist for more than perhaps a few hundred yards inland.

Yet the War Office still felt that the urgent need for agricultural labourers in the east outweighed the risks of malaria. In another letter it was suggested ‘that prisoners from Lybia born north of the River Po and apparently free from malaria may be sent to Doddington’.

By now it was 10 July and the situation was becoming urgent. It was arranged that Mr Shute, along with a Dr Banks, would inspect the camp location and conditions and report back. But as the same letter summed up forlornly:

I don’t know that there is anything that can be done except for the Medical Officer of Health to keep a general surveillance on the prisoners in case any of them show signs of infectious disease … If in spite of the care taken to select them there is any case of malaria, great care should be taken that it is removed as soon as possible and I think you better let me know at once.

It was 22 July when Mr Shute penned an urgent report to Dr Stock on the situation:

I met Dr Banks at Cambridge on Monday July 21st. We visited two proposed sites …

The Doddington Site

At one end of the field which had been selected, there is a large marsh. Anopheles Maculipennis are numerous and adults are plentiful in the farm buildings close to the field.

The Ely Site

There is a swamp on the proposed site and A. Maculipennis are equally numerous here.

Comment

Anopheles are very numerous in both these areas and breeding is taking place in the fields where it is proposed to erect the camps.

Both sites are potentially dangerous.

It is too late in the season to clear up the proposed site. Even if anti-larval operations were carried out at once it would not be satisfactory because adults are so very numerous and most of them will live on for the remainder of the summer.

Scrawled in heavy black ink at the bottom of the letter, Stock added his own thoughts: ‘the proposed site does not seem to be at all suitable.’

When Dr Banks wrote his report he pointed out even more reasons, aside from mosquitoes, why the site was unfit for a camp:

The site [at Doddington] which was small and low-lying, looked liable to flooding in winter time, but no-one was able to confirm this. The only definite proposal for essential services already considered was the supply of main water from the Town and no arrangement had been made for sewage disposal. From the nature of the land it did not appear likely that satisfactory arrangements could be made for this, especially when … the possible presence of enteric carriers required extra care in this connection.

I had had in mind a number of other possible objections to a camp of this kind in the Isle of Ely, namely lack of hospital provisions, particularly isolation, lack of essential services, etc. but it was not necessary to discuss these.

The combined reports were damning. Shute believed that any site located in Ely would be dangerously close to mosquito grounds, while Banks felt the areas were too isolated and rural to provide suitable living quarters.

In the end, however, the War Office decided that the risks of malaria should not outweigh the need for a camp in the Ely area. The camp location was changed from Doddington to ‘Old Militia Field’ Ely. This did not go down well with everyone; writing to Dr Banks, Dr Goodman of the Ministry of Health was appalled and astonished at the way the malaria risk was seemingly being ignored.

But the decision was made and Goodman received a letter notifying him that the prisoners would be arriving at the camp from 23 August. The Ministry of Health still hoped that they might be able to get permission from the military authorities so that Mr Shute could go down and take ‘blood films’ from the prisoners and test it for malaria. Mr Shute wrote:

It is to be hoped that the local doctors [at Ely] will at once notify any cases of fever in the village (especially children) where the cause of the fever presents any difficulties. I wonder if the military would be prepared to spray with ‘flit’ the animal houses in the farm close to the site. If they would do this in October, just after Maculipennis have gone into hibernation, and again in March, just before they come out again, the adult population would be much reduced next summer, at least for two or three months before migratory swarms appear.

There were perhaps some who considered their fears slightly exaggerated. Writing on 11 September 1941, Lieutenant-Colonel Sandiford stated:

You will be interested to know that of 1,454 Italian prisoners of war received at 17 camp, Prees Heath Shropshire, on 6th September, 1941, 42 were recovered para-typhoid cases treated at Durban, South Africa, and of 1,000 prisoners of war received at 16 camp, Lodge Moor, Sheffield, on 9th September, 1941, 33 are similar cases.

As you know, a careful history of each man is taken and those with a history of enteric or dysentery infection are examined to ensure they are not ‘carriers’ before allowing them to proceed to their various labour camps.

Mr Shute took blood films in September from the prisoners and wrote to Dr Roxburgh, the lieutenant in charge of Old Militia Field labour camp, with his initial findings on 28 October:

I have not yet finished examining all the films of the prisoners … But I thought you may like to know that we have examined a hundred (thick and thin) and that so far no Plasmodia have been found.

As you know, between relapses, parasites are very rarely found in the peripheral blood and therefore a parasite free blood is not evidence that the person has not had malaria, or that he will not relapse in the future. I mention this because if any of them develop fever which is not readily accounted for, you may like to have a blood film examined for parasites.

Mr Shute was also asked in December 1941 to draw up a map of England and Wales showing the areas where malaria was likely to be a risk. By January thoughts were returning to preventing mosquito breeding and it was proposed that notices be sent to the camps outlining how to stop mosquitoes breeding in the static water tanks.

At last the procedures for ensuring prisoners did not bring disease to England were formalised in March 1942. All prisoners had to be inoculated against enteric bacteria in South Africa. A brief medical history of each prisoner was to be prepared by the Italian medical officers during the voyage to England. The men were expected to have been cleansed of vermin in South Africa, but routine disinfestation was to be performed in the ports where the men arrived. In the case of typhus, however, it was expected that each POW would be given a careful examination when they arrived at their camp and a ‘Serbia barrel’ would be set up to bathe men with suspected infestation. Night soil was to be incinerated and any cases of minor illness would be dealt with at the camp. Anything more serious would be treated at the nearest military hospital or EMS hospital.

Ely was not alone in attracting malaria concerns. At the camp at Horsham, Sussex, which already contained Italian prisoners, a ditch was discovered to contain breeding mosquitoes and Dr Hope Gill, who was in charge of the medical side of the camp, was put on alert that should any suspected malaria cases arise, blood films should be taken at once.

It was not only in the east where camps had to be reconsidered. The proposed Melton Mowbray and Rugby camps were already being replaced by proposed camps in Garrendon Park, Loughborough, and Fenny Compton, Warwick, as the Shute and Banks reports on Ely were being read. Only a week later the War Office changed its mind again – there would be no camp at Fenny Compton and instead one would be set up at Ettington Park, 4 miles north of Shipston-on-Stour. In fact, it seems the various authorities were getting quite muddled with their camp locations. A hasty memo from the Ministry of Health read: ‘We have been in touch with Wiltshire as regards the Farncombe Down camp ((a) on your list) and have been informed that Farncombe Down is in Berkshire, just over the border from Wiltshire.’11

However, one site in the east did meet with approval. Shute wrote of the Royston site in Hertfordshire: ‘This appears to be an ideal site and there are no mosquito breeding grounds in the area. It is waste ground very dry and chalky.’

There remained anxiety about the spreading of disease; in particular, the disposal of sewage from the camp caused consternation. Concerns were raised about the disposal of urine, though ‘it may be possible to sterilize the urine by bleach before allowing it to discharge into a soakpit’.12

A PRISONER’S INSIGHT

When renowned German theologian Jurgen Moltmann published his autobiography, it included a chapter on his experiences as a boy serving in the German army and ending up as a British captive. German accounts of their time as prisoners in Britain are few and far between; the account in A Broad Place gives a great insight into the experiences, living conditions and attitudes of the prisoners.13

Jurgen Moltmann was only in his teens when he was called up in July 1944 and found himself a German soldier rather than a student of mathematics as he had intended. He spent much of his first days at the barracks learning to drill, dismantle and assemble machine guns, and how to identify different ranks within the German army. Despite almost being sent to the front for further training in August of that year, it was not until September, after the British had launched Operation Market Garden, that he found himself heading for battle.

First travelling by train in a cattle truck, then marching 35km and encountering scattered soldiers retreating from the fighting, some wounded, Moltmann’s unit eventually arrived at the Albert Canal and dug themselves in. That night they came under heavy fire for two solid hours; Moltmann, lying in his dugout, managed to fall asleep only to be woken by his corporal shouting ‘out and back’. Confused and alarmed, the men followed the corporal into nearby woods, finally running through to the village of Asten; there they heard grenades whistling overhead all night and falling into the village. Distantly they could hear the sounds of fighting on the canal bridge.

The men became lost; with no one apparently in command they drifted about trying to re-form their unit. By morning those who had survived the night came together. Only half their number was left; any man sleeping close to the canal bridge during the onslaught had been killed. With British tanks rumbling in the distance, the young men dispersed across the fields and made their escape in the dead of night.

Later, they learned their commanding officer had taken refuge in a cellar in Asten waiting to surrender to the British.

Near escapes were to become a pattern of Moltmann’s short army career. During the remainder of 1944, until February 1945, he served in Holland before participating in the Battle of Venrai. Moltmann recalled taking shelter in a farmhouse with several other soldiers; they were in the midst of the British and while hiding heard a swathe of tanks rumbling towards them. At the last moment the tanks turned away, much to the men’s relief. Moltmann peered through the glass in the building’s door to see what was happening and to his surprise saw British soldiers looking back.

The Germans ran out the back door with sub-machine gun fire at their backs, through a pigsty and behind a haystack. That night they crept past the village that was now occupied by the British, lit by the flames of burning haystacks.

Moltmann was later part of a reconnaissance troop sent out to scout the enemy. They came across no one until they hit an open path; there a Red Cross ambulance had struck a mine. The two British drivers lay on the road dead. The troop carried on and eventually came across a knocked-out English tank perched on a small hill. Being close to the British lines, they hid behind it and listened for a while, but came away with no information.

With their territory under pressure from the British, the German forces found themselves pushed further and further back. In January Moltmann was once again sent out on reconnaissance work, this time to see which nearby villages had been occupied by the British. Wearing snow-shirts and rubber boots, and led by a soldier named Fritz Goers, the troop crossed a river in rubber dinghies and walked to the nearest village. At first it seemed peaceful; they searched a few houses but found nothing so walked further down the main road. Suddenly a flare attached to a mast went off and the men dived for cover in a field. Gunshots rang out from the houses and rained down on them until Goers called out in English that he was wounded and needed help. The shooting stopped and in the darkness Moltmann and another man crept away and back to their unit.

Moltmann’s experiences of war were not just the constant struggle to avoid being captured by the British, but also the day-to-day deprivations and miseries that stuck with him. For six months Moltmann never slept in a bed, only in a dugout; if he was fortunate, on dry straw. When military reinforcements joined them from the east they brought with them lice which were impossible to get rid of. The German delousing stations could do little better than offer the men a shower and clean their uniforms. So the men sat in their trenches and ‘cracked’ lice.

Moltmann began to suffer from boils on his neck. The medical orderlies attempted to cure them by painting on a tincture, but to little effect, so Moltmann spent most of his time wearing a gauze bandage.

In February 1945, with the British getting ever closer, Moltmann’s unit marched to the village of Cleves. Coming under heavy fire, they fled to a hill where an observation tower stood and parachutists were awaiting orders. They were still under fire and shot blindly into the dark. As the night wore on, a unit of British tanks roared up the hill and occupied the tower. Moltmann and his colleagues now realised they were hemmed in.

When morning came it was discovered that most of the officers and parachutists had already decamped, leaving the ordinary soldiers to fend for themselves. They formed small groups and attempted to break through the British lines. Moltmann’s unit only succeeded in reaching a field in front of the hill where a cemetery stood. The British began firing on them from all sides and several men fell. Others put up their hands to surrender. Moltmann and a few others made a dash for a semi-ruined house nearby and hid inside.

As the firing grew fiercer the other men threw their rifles out of the windows to show they were prepared to surrender. Moltmann slipped up to the attic of the house and found a sheet of iron to hide under. The British entered the house and shouted for the Germans; Moltmann remained under the sheet of iron and managed to stay undiscovered. As night fell he slipped from his hiding spot to see if he could escape, but only went as far as the cemetery because the road beyond, which he would have to cross, was far too busy with British traffic.

Returning to the ruins, he searched the property hoping for something to eat or drink. Finding nothing, he went up to a room beneath the roof and lay there in the dark. The next day he watched the British advance into the Reichswald Forest from the window in the roof.

Moltmann knew he had few options remaining; if he did not escape that night he would have to surrender. He was tired, hungry, thirsty and crawling with lice, all things that depleted his resolve to stay undetected by the British. That night, however, he did manage to cross the cemetery and the road beyond; he found himself between abandoned tanks and started to make for the front once more.

Again, Moltmann’s journey was fraught with near misses when he came close to stumbling on British soldiers. While walking through woodland he saw the British approaching and lost his glasses leaping into a bush for cover. Later he trudged through a British communications line where everyone was asleep in their tents and never knew of his presence. But things were now getting bleak for Moltmann; he was on the brink of exhaustion, his only sustenance being snow water from puddles.

While searching for a place to hide in a dense part of the woods he was surprised by a British soldier. Moltmann shouted, ‘I surrender’. But the soldier mistook him for one of his mates messing around. He called other men over and they began to talk to Moltmann, realising he was one lone German.

Moltmann was uncertain of what would happen to him, but the men treated him well and the following morning their lieutenant gave him a mess tin of baked beans. It was the first food Moltmann had tasted in days.

Later he was taken to the assembly point for prisoners. The British there were armed with DDT sprays for delousing the new captives. When sprayed under the clothes the DDT quickly dealt with the lice, survivors crawling out of the men’s collars and cuffs. For the first time in many weeks Moltmann felt the relief of being free of the terrible pests.

It was 15 February 1945 and with mixed feelings Moltmann now began his life as a POW. He was first transferred to camp 2226, Zedelgem, near Ostend. No longer faced with death and the struggle to survive, the prisoners found themselves confronted with a new problem. Becoming prisoners gave them a chance to think and dwell on what had happened and what the future held. Despair engulfed many, some even fell sick because of it; for those from East Prussia and Silesia the future looked bleak. Their homelands were now occupied by the Russians, the natives driven from their homes. These men had nothing left and no idea of what they were going to do.

For others the thing that tormented them most was the memories of lost comrades. In the heat of battle death had to be swept aside as you leapt from conflict to conflict; in the camps there was time to think. Many men were suffering from ‘survivor’s guilt’, wondering why they had survived and their comrades had not. Many too were suffering from post-traumatic stress syndrome, a condition unrecognised at the time but which led many into a spiralling state of depression and despair.

Moltmann was one of these men. At night he suffered horrific dreams when he saw the faces of the dead and would wake in a cold sweat. He felt alone, his hopes and dreams for his future dashed and, like so many of the men, was struggling to come to terms with what might lie ahead.

The Belgian POW camp held its own horrors. The men slept in huts on three-tier bare wood bunks; there was scarcely any other furniture and the bunks had to double as seating. At night the huts were locked, the only sanitation coming in the form of two buckets. It was after dark when the horror really began. Many of the prisoners were former Hitler Youth leaders or SS men, and when the hut doors were locked they went after anyone who was critical about Hitler, the Nazi party or Germany’s chances of arriving victorious at the end of the war. The screams of men being beaten up echoed through the huts.

Moltmann shared a bunk with an engineer from Augsburg, an older man no longer subject to the reckless heroism of youth. He would not allow Moltmann to go to the aid of any of the attacked men, knowing the savagery of the assailants. He would hold him forcibly down in his bunk if necessary to prevent him getting involved.

Moltmann had sunk into the grips of depression. The boils that had constantly plagued him in the trenches now spread across his body, but he did not care to do anything about them. Eventually it was the Augsburg engineer who once again looked out for him and escorted him to the medical orderlies. Moltmann’s condition was severe enough for him to be sent to a hospital in Ostend. There he was able to take a bath and, with fresh clothes and a decent bed, he slowly healed, finally returning to the camp scarred but well a fortnight later.

The end of the war brought new problems for the prisoners. The Red Cross in Belgium declared that, as there was no longer a Germany, they were not responsible for the prisoners anymore and abandoned the camp. Left in the care of the Belgian authorities the prisoners found their rations cut, and the British porridge they had become accustomed to eating in the mornings was watered down.

From time to time people were taken out of the camp to work. On one such occasion Moltmann was in a work party pushing a goods truck when he came upon a blossoming cherry tree. Struck by its beauty and brilliance, he stopped to admire the tree and it was at this point that the depression in him began to lift and he started to come alive again.

During the summer of 1945 groups of prisoners began to be sent home; Moltmann, however, was never among them. Camp life was tedious and boring, so he joined a choir and pretended to sing to pass the time, but most of his daily life was employed waiting and hoping that the next call would be for him to go home.

In August Moltmann was summoned along with others to get onto a transport at Ostend. Finally, expecting to be travelling home to Germany, they boarded the ship. The next morning when they went on deck they were shocked to see Tower Bridge. They had arrived in London.

The prisoners were taken to Hampton Park where they were searched for watches or valuables, before being sent on another journey up north, finally arriving twenty-four hours later at a camp in Ayrshire, Scotland. This was camp 22, Kilmarnock.

While not his home, the British camp was far better than its predecessor in Belgium. The Nissen huts only held twenty men each and they slept on individual beds with straw palliasses. In the centre of the hut stood an iron stove to provide warmth.

At Kilmarnock the men’s mental well-being was taken into more consideration and the site included a recreation ground, a library, a POW orchestra, a canteen and a chapel; an attempt was also made to stimulate the men’s minds with lectures and talks. Moltmann often sat with other prisoners listening to a Catholic professor of philosophy talk about the ideas of Aristotle and Aquinas.

Despite this the camp could still feel claustrophobic and Moltmann regularly volunteered for work outside the camps. His favourite role was as an electrician in a NAAFI camp where he only had to follow a skilled workman about, move light cables and mend electric irons. He also had a friend in the camp who stored away tins from damaged boxes. He often gave Moltmann a tin of corned beef or sardines which the German would discreetly eat in the lavatory.

There was plenty of work to be done in post-war Scotland, so Moltmann fulfilled many roles. At Dumfries House he cleaned parquet flooring, at a Scottish mine he dug coal and at a cement factory he came away covered in grey dust. At New Cunnock, a German working party dug sewage trenches for the laying of pipes for a new housing estate. Moltmann was among them performing the back-breaking task of digging through partially frozen earth, while another team worked on creating the roads for the estate.

The work teams were always hungry from their intensive labour and Moltmann regularly approached the Scottish or Irish overseers asking for bread. This became such a common occurrence that soon Moltmann had become the interpreter for the work gangs and no longer had to work himself. Instead he acted as a go-between for prisoners in the camps who were constructing toys and the Scottish families who were happy to buy them and provide the Germans with a small income.

During his time in Scotland Moltmann became friendly with a local family named Steele; they called him Goerrie and treated him as a friend. When he appeared one day with a runny nose because he had no handkerchief, Mrs Steele gave him a new packet of hankies to keep. She also sent uncensored letters from him to Hamburg – a charitable act that could have got her into a lot of trouble with the authorities.

In fact, the Scottish families of Kilmarnock on the whole treated the prisoners with hospitality and kindness. Their friendliness to former enemies made many Germans feel ashamed, but at the same time it brought them out of their isolation and reminded them what it was to be human and part of a community.