Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

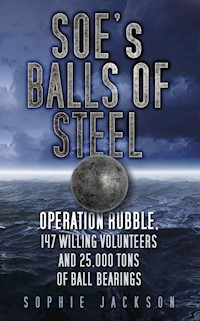

In 1940 the Nazis hoped to cripple the British war effort by blockading Swedish cargo ships containing ball bearings, steel and tools vital for making arms and equipment. In desperation the newly formed SOE was asked to rescue these badly needed supplies and a daring escapade was dreamt, which involved sneaking in under the Germans' noses to steal the ships. It was a dangerous mission and the 147 men involved knew there was a high chance they would not come home. The terrifying operation to rescue cargoes of ball bearings in clunky transport ships, while trying to outrun the Luftwaffe and German navy, had never been attempted before. It was a success that was never repeated. Making use of newly released files from the National Archives, Sophie Jackson tells the story of a forgotten adventure that saved Britain and her troops from certain defeat, all because of brave men willing to sacrifice their lives for millions of small balls of steel.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 415

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title Page

Acknowledgements

1 Through Snow and Ice

2 The Heart of the Issue

3 Norway’s Swan Song

4 ‘In the Name of God, Go!’

5 A Shadow Over Sweden

6 A Friend in the Hour of Need

7 Operation Rubble

8 Planning a Performance

9 Operation Performance

10 Aftermath

11 Bring On the Cabaret

12 A Whole Load of Moonshine

Select Bibliography

Plate Section

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

When I began this book I was aware that finding sources for information would be tricky, particularly as the men involved were largely merchant seamen and Norwegian. For that reason I have to thank Siri Holm Lawson, whose website warsailors.com has been an invaluable source for the Norwegian side of this story. Lawson’s comprehensive work on the men and ships involved in Operation Performance, taken from Norwegian sources otherwise inaccessible to a British writer, has enabled me, for the first time, to present the story of the non-British volunteers who made George Binney’s operations possible. Lawson has also kindly provided me with a number of images of the ships involved.

Newly released files from the National Archives have also been instrumental in forming a picture of those daring Scandinavian adventures. The perspectives of the British seamen involved came through in detailed reports and have helped to flesh out the human side of this story. In addition, the books by Marcus Binney and Peter Tennant have been invaluable in filling in the gaps and confirming the technical and legal details of the adventures. Lastly, a writer is always indebted to many sources, and my thanks go to those responsible for the many archives and books I scoured for odd references and personal stories during the writing of this story.

1

THROUGH SNOW AND ICE

The Swedish coast in winter can be a barren and bitterly cold place. It was January 1941 and the Bro Fjord, just off the Skagerrak strait, was thick with 6 inches of ice. The skies had been particularly clear and the scene was almost picturesque as crewmen from the various ships anchored in the fjord took the opportunity to stroll across the ice to neighbouring ships or to shore. If only the Nazi presence had not been such a constant worry in Swedish minds it could have been a peaceful situation.

The arrival of dozens of Norwegian merchant sailors in Sweden over the last few months had been an unpleasant reminder that Hitler was not opposed to invading a neutral country. Norway had been in Nazi clutches for under a year, but its people looked harassed and nervous, their morale broken. Few civilians onshore paid much heed to the sight of the depressed-looking Norwegians moving about the cargo ships, nor to the loading of those same vessels. Any curiosity they showed fell instead on the British crews who milled among the Swedish and Norwegian sailors. For many months now there had been an embargo on allowing any ship bound for Britain to leave the fjord. Hitler was anxious his enemies did not receive the vital iron cargo they had bought from Swedish mines and factories. It was intended for use in the manufacture of weapons and armaments to fight the Nazi war machine. Sweden, caught in an unhappy position between the Allies it favoured and the Nazis it feared, had banned the export of the iron despite it already being paid for by British coin. Not wishing to use force on the British, the Swedish authorities had spun a web of legal complications as to why the cargo ships could not leave. A web Britain was busily trying to unravel.

All seemed quiet and usual as it began to snow at Bro Fjord. The restrictions were still – apparently – soundly in place. The few Swedes outdoors hurried home in the dark and cold, looking forward to their warm fires. A stillness fell over the port.

A short time before 3 p.m. an engine rumbled into life. The snow was falling heavily now and no one was watching as the slow and heavy cargo ship Ranja manoeuvred her way carefully out of the ice and slowly inched into the Skagerrak. Even if she had been noticed ashore few would have been concerned; Ranja was carrying only salt water ballast.

A few minutes later more engines were rumbling into life. The cargo ship John Bakke pulled free from the ice and followed the Ranja; then the Taurus, piloted by her First Officer Carl Jensen, joined the convoy. Next was the Elisabeth Bakke, pulling from her icy berth to join the grand departure, and last to come was the Tai Shan commanded by her enthusiastic Swedish First Mate, H.A. Fallberg, who had been left in charge while her master was away. All were Norwegian vessels, but the Swedes would have been worried to know that three of them were being sailed by British captains, their Norwegian captains having been roughly removed for being ‘uncooperative’.

They would have been even more disturbed to know that aboard the Tai Shan stood the representative to Sweden of the UK Ministry of Supply (Iron and Steel Control), Mr George Binney. Binney had been working tirelessly behind the scenes to convince the Swedish authorities to release the valuable iron cargo due for Britain. His presence on a Norwegian ship mysteriously vanishing into the gloom of a wintry afternoon would have raised warning flags for any Swedish authority who noticed him.

Binney had been working for months trying to find a way to secretly remove the embargoed iron from under the Swedish and, ultimately, German noses. Political, legal and even moral arguments had been presented both for and against the operation in British circles, but finally the pressing need for the supplies and the dogmatic refusal of help from the Swedish Government tipped the scales in Binney’s favour. The 40-year-old Royal Naval Reserve commander and former Arctic explorer was only too elated to finally get some action. Diplomacy had been tiresome and unproductive; now Binney was heading an expedition to release what rightfully belonged to the British.

He knew the backlash from the Swedes and, even worse, from the Nazis would be dreadful. The possible reprisals had been weighed in the balance during the planning process and ultimately the gains had been considered to outrank the potential risks. Yet as Binney stood on deck of the Tai Shan, freshly shaved and wearing a clean shirt and his best blue suit, he knew that slipping out of the Bro Fjord was the easiest part of his operation. Soon they would be in the open Skagerrak strait and the Germans would endeavour to stop them.

OPERATION RUBBLE

At 5.45 p.m. the Tai Shan dropped off her pilot and Chief of the Gothenburg Harbour Police, Captain Ivar Blücker, at Lysekil. Blücker had been instrumental in the scheme and had earned Binney’s respect and trust. Operating under his instructions from the Swedish Government to ensure their waters remained truly neutral, he had kept a close eye on proceedings and ensured no attempts at sabotage were made while the five Norwegian vessels were being loaded.

Blücker was painfully aware that every move Binney was making was being monitored by German agents and that the scale of the operation would prevent it ever being truly secret. Even so, he was determined to help the British as much as he could, volunteering to travel on the Tai Shan through Swedish waters to ensure she was not hampered by any opposition. When he stepped off at Lysekil it was dusk and visibility was barely 1½ miles. He watched the Tai Shan vanish into a new shower of snow, wondering if her crew and his new friend Binney would survive the coming German blockade.

The Nazis were inherently suspicious of Swedish neutrality and with good cause; they knew they were not terribly popular among the Scandinavian nations. Norway had already proved itself faulty when it came to honouring its neutrality equally among the warring nations – an excuse Hitler had used for invasion. Sweden was a slightly different prospect. Overrunning Sweden, like Hitler had done in Denmark and Norway, was never really on the cards after the invasion of France and Hitler’s expansions across Europe had stretched Nazi manpower. But there were still the worries over Britain’s iron supplies. Sweden was so far honouring its embargo, but there was nothing those dastardly British wouldn’t try to get what they wanted. As an extra line of defence the Germans had created a blockade just outside neutral Swedish waters and regularly patrolled it to prevent just the sort of escapade Binney was masterminding.

Aboard the Tai Shan visibility had reduced to just ½ mile. The other ships in the flotilla from Bro Fjord were impossible to sight and, without any wireless communication, Binney could only assume they had left the Swedish coast successfully. Everyone (aside from the engineers on watch) was wearing life-jackets, anticipating the worst. If the Germans made a successful attack on them they had orders to scuttle the ship rather than let her cargo fall into Nazi hands. The night was dark and no one could sleep; instead, those who weren’t needed below decks stood on deck scanning the waters for potential signs of danger. The night was perfect for German motor torpedo boats (MTBs) and at any moment it was expected the ships would come under attack.

There had been endless problems finding loyal crews for the five blockade-running vessels. Many of their original men had refused to sail due to German pressures and a general attitude among some of the Norwegians that it wasn’t worth their while to help the British – this was a left-over grudge from the seeming lack of help the British had given during the Nazi invasion of Norway. Almost as fast as Binney and the few Norwegians loyal to him recruited crewmen they would leave and refuse to work on the ships. In desperation Binney had put together a reserve crew of British sailors who had been trapped in Sweden when the embargo was dropped and the Germans began the blockade. The ultimate result was that the engineers operating the Tai Shan’s engines were unfamiliar with the craft, and her Norwegian captain, Einar Isachsen, made the decision that there was no point trying to force extra speed from her when the men below were so unprepared. Instead they crept along at 13½ knots (Tai Shan’s top speed was 14 knots). In a short time the Tai Shan passed close enough to the John Bakke and Ranja to sight them through the darkness and snow, but they were unobserved. The Scandinavian night was so thick that it was impossible to see anyone until they were almost upon them. Just such a night had been chosen on purpose for the advantage it gave the British as they tried to evade the German blockade undetected, but it also meant a Nazi MTB could approach them without being spotted until it was too late.

As the night began to fade away the weather lifted, and by 4 a.m. the flash of two Norwegian lighthouses could be observed indicating, as the crews of the ships had hoped, that they were on course to sail down the Norwegian coastline. They were 28 miles south of the coast and awaiting the arrival of the aircraft of British Coastal Command to provide them with an escort for their daytime journey. But with each passing minute, with no planes in sight, it became clearer and clearer that an airborne escort was not coming. Captain Isachsen found Binney on deck and complained bitterly about the missing aircraft. Using all his guile, Binney laughed off the matter. He told him: ‘They [are] doubtless overhead, but at such a height as to be both invisible and inaudible, and … British submarines [are] probably in our vicinity keeping guard over us, though we [can]not see them.’ Isachsen was, unsurprisingly, rather unimpressed. Binney only later learned that snow storms over England had prevented Coastal Command from launching its planes. Similar snow storms inland over Norway were also hampering German air operations. Fate does tend to have a sense of humour.

It was now full daylight and it was possible to see for 30 miles across the icy waters. The loss of darkness and the clearing of the weather meant the small convoy was a prime target for any watchful Germans. The lack of an air escort made Binney anxious. The five rugged little ships were no match for the Luftwaffe or a German patrol craft and there was still around 55 miles to sail before the convoy could meet up with their naval escort.

On the stern horizon Binney could see one of the slower ships in the group silhouetted against the bright sky. Perhaps it was the Ranja or John Bakke. Several miles ahead he could make out the Taurus ploughing through the waters. They were now so obvious in the bright sunlight that Binney anticipated a serious attack from the Luftwaffe at any moment. Without the aircraft of Coastal Command to ward them off, the little ships would be easy prey. ‘It was Mediterranean weather with blue sky and clear seas,’ Binney later reported. ‘Our salvation lay in the fact that it was snowing on the Norwegian coast and that no air patrols were active.’

The last leg of their journey before rendezvous with the Royal Navy put them in constant range of the Nazi-occupied airfields at Egersund or Stavanger. That no Luftwaffe challenged them at that moment – when the weather was so clear they could be seen for miles and there was no hope of being defended by the distant Navy escort – was due more to luck than anything else.

That wasn’t to mean that there would be no Luftwaffe activity at all. Late in the morning a solitary German aircraft appeared in the sky. Everyone braced themselves for the worst, but it was over the John Bakke that the aircraft hovered. The John Bakke was flying her Norwegian flags, as were all the ships in the tiny fleet. As they waited in horror for the ship to be struck, nothing happened. The German plane maintained its position above the John Bakke for another 2 hours, acting as an escort. Binney could only suppose that the pilot had wrongly assumed that the cargo ships were in fact operating in the service of the Nazi occupiers of Norway. As the fleet was currently on a north-westerly course along the coast of Norway this was a logical assumption, but Binney knew it would not last. Eventually the ships had to turn westwards to cross the North Sea and it was then that the Luftwaffe pilot realised his mistake. He turned his attention on the slow Ranja as his best target.

The Ranja’s fate had always been precarious. The slowest vessel in the fleet, she had the unenviable role of being a decoy for the other ships. As she slogged along at her trembling 11½ knots at the back of the convoy her crew realised it was only a matter of time before the Luftwaffe picked on her as the weakest member of the group. From the start the Ranja had been deemed expendable: filled only with salt water ballast it would not matter if she sank to the bottom and her demise would buy valuable time for the remaining vessels carrying genuine war supplies. But that was cold comfort to her civilian crew who now saw the German plane circling above them.

The Luftwaffe aircraft dropped its bombs, but they proved wildly inaccurate – not uncommon in aerial attacks against shipping – and they appeared to fall harmlessly into the sea. Resorting to his machine guns the German pilot began strafing the Ranja with a deadly hail of bullets. Against the unarmed Ranja it was a horrific attack. Bullets pierced the flimsy hull and there was nowhere for the crew to hide. On the bridge First Officer Nils Rydberg, a Swede from Gothenburg, was trying to keep the Ranja on course when fragments from a bomb that exploded away from the actual ship flew through the walls of the cabin and caught him in the abdomen. He collapsed in agony, his blood rapidly pooling on the floor.

Thankfully at that moment some British planes finally arrived, the weather having cleared enough for Coastal Command to restart its operations. Outnumbered, the Luftwaffe craft was driven away, shamefaced at the dramatic error it had made over the identity of the ships, knowing that the British were endeavouring to make a daring escape.

Binney felt he could relax. Unaware of the dying Rydberg, it seemed at first sight that the mission had been an unprecedented success. Around noon he followed Captain Isachsen below decks for some food. They had barely begun their meal when a crewman scrambled down to them.

‘A man o’war in sight!’

Binney could have laughed with delight. He was certain, so near were they to the rendezvous point, that this had to be one of the British escort. Isachsen rushed on deck but Binney continued eating his meal, content that he had outrun the Nazi threat and was close to victory. It was 12.20 p.m. when the British destroyer challenged the Tai Shan. Captain Isachsen hastily flew their identification flags, a startling white sheet with the big letters ‘GB’ emblazoned on it. As Binney later pointed out, these could have stood for many things, but he chose to believe they stood for George Binney. This was his proudest moment; from being trapped at the start of the war in a fruitless desk job he had jumped to being commander of his own little fleet and defying the Germans. As several more of the escort vessels sent by the Navy hove into sight he couldn’t help but contemplate that this was his fleet joining with his country’s fleet: ‘It became apparent to us how thoroughly the Royal Navy were redeeming their promise to protect us once we were out of the Skagerrak.’

The worst seemed over; the tense voyage unescorted through Nazi territory had passed uneventfully and now they were in open waters and surrounded by an impressive escort of Navy vessels. But the apparent negligence of the Germans in stopping the escaping convoy would not last forever. Only moments after the Tai Shan crept into the sheltered protection of the British destroyers and cruisers a submarine alert was sounded. One of the cruisers was under attack and retaliated with its own heavy fire: ‘… it was grand to see all its guns blazing off simultaneously, their flames belching red and orange through clouds of smoke. I do not know the result, but the cruiser was not hit.’

Almost as soon as the attack had begun it was over. The submarines perhaps thought better than to take on the large flotilla of heavily armed warships, especially as the British were now perfecting their ASDIC (anti-submarine detection) strategies and were better able to target U-boats. In any case, Binney was relieved that they had encountered such faint opposition, and the rest of the journey home proved surprisingly peaceful.

A SURPRISE PACKAGE

At 6.30 a.m. on 25 January 1941, Binney could look on the shores of Kirkwall, Orkney. His audacious voyage had surpassed all expectations and every ship had arrived in one piece with her precious cargo intact. As the Tai Shan moored in friendly waters she was joined by the Taurus. Two hours later the Elisabeth Bakke, the John Bakke and the forlorn Ranja appeared in Scottish waters. The Elisabeth Bakke had in fact made such good time that she had reached the Orkneys the previous evening and had waited off-shore throughout the night for the rest of the convoy.

Binney was naturally elated. In the cargo holds of the ships were 24,800 tons of Swedish pig iron, special steels, ball bearings and machine tools – effectively a year’s worth of supplies from Sweden that were desperately needed for the war effort. The cargo was valued at £1 million and the worth of the ships that had been removed from the grasp of the Nazis was £2.5 million; 147 men (fifty-eight British, fifty-seven Norwegians, thirty-one Swedes and one Latvian) and one woman (the wife of the Chief Engineer of the John Bakke) had taken part in the mission.

It was a huge coup for the British and particularly for the fledgling SOE (Special Operations Executive) that had helped to organise the mission. Binney, quickly moving for another mission on similar lines, viewed the lack of German interference less as a fluke and more as an indication of how choosing the right weather to operate in could be fundamental to his success. He was pressing for a second mission as early as March. However, his superiors were more inclined to count their blessings at obtaining one shipment with so little human loss and were not as convinced that it had been anything but fate that had spared the convoy from more serious harm.

The Germans were naturally furious about the escape. Their Foreign Minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, was outraged. He confronted a member of the Swedish Government unfortunate enough to be in Germany at the time, conducting negotiations on behalf of his country. Lashed verbally by Ribbentrop at the laxity of Sweden at allowing five ships to escape their embargo and sail to Britain, the Swedish minister promised a full explanation once he was able to return home and talk to his colleagues.

When, a short time later, Ribbentrop received the full report from the Swedes on the matter his fury was whipped to new peaks – the Swedes explained that the German Government had been fully aware of the British attempt and had told the Swedish Government about it. They added that though they had hoped the British would not succeed in setting sail, they had believed it was the German Navy’s responsibility to deal with them when they did. Therefore, concluded the Swedes, it was all the German Navy’s fault that Binney’s mission had succeeded.

The enjoyment the British took at fuelling German tempers was almost as great as the elation of capturing such valuable supplies. Binney was still considering the possibility of another attempt, and was due back in Sweden where he would return to his role as UK Minister of Supply, but the idea of further iron ore missions kept turning over in his mind. ‘Hope springs eternal,’ he remarked to SOE before boarding his aircraft for Sweden. ‘But don’t forget that though you use the same pack, the cards fall differently every deal.’

Meanwhile the unfortunate Nils Rydberg lingered in a hospital at Kirkwall, his wounds serious and life-threatening. He asked that his relatives in Sweden should remain ignorant of his condition, though there was no option but for Binney to inform the Swedish minister in Stockholm. On 7 February, when Rydberg took a turn for the worse and perished, a telegram was issued to Stockholm from the Foreign Office asking that Rydberg’s family be informed and that any of his dependants should be provided for within the limitations of his mission contract. Nils Rydberg was the first and only casualty of Operation Rubble, but his sacrifice had not been in vain.

2

THE HEART OF THE ISSUE

George Binney’s mission was a response to an issue that plagued both the Allies and Axis governments throughout the war: the urgent need for steel to maintain production of military weapons and vehicles.

Britain and Germany both relied heavily on Scandinavian sources for their iron ore and steel, and both quickly saw the potential for outflanking the other by severing these supplies.

Prior to the war, Sweden exported thousands of tons of iron ore. In 1938 alone, a total of 11,976,000 tons was shipped, of which 8,441,000 tons, about 70 per cent, was sent to Germany, while Britain received 1,603,000 tons, just over 13 per cent. During January 1939, Germany took receipt of 487,890 tons of Swedish iron ore and, in February 1939, received 475,482 tons. (In comparison, Britain received 67,730 and 70,234 tons respectively.) In the 1930s, 10 per cent of all British imports came from Scandinavia in the form of food (bacon, butter, eggs and fish) or raw materials including iron ore and timber. If these supplies were ever cut off it was believed that the fighting forces would suffer.

At the same time, as can be seen from the figures above, Germany’s situation was far graver as its reliance on iron ore imports was on the rise, soaring from 14 million tons in 1935 to 22 million in 1939, with high-grade Swedish ore accounting for 9 million tons of the total. The ore was mined from the Kiruna-Gällivare district of Lapland, north of the Arctic Circle. Railway lines enabled the mined ore to be transported through Luleå in the Gulf of Bothnia or Narvik in Norway. Narvik was vitally important as during the long Scandinavian winter the Gulf of Bothnia froze over, making Luleå ice-bound from November to April. Narvik became the sole route for supply ships. During the winter of 1938–39, 6.5 million tons of Swedish ore were shipped via Narvik, 4.5 million of which was destined for Germany. After the outbreak of war a steady pressure was applied to Norway to cease, or at least limit, the amount of Swedish iron ore it allowed to be shipped via Narvik to the Germans. Norway was endeavouring to remain neutral, but with a discreet bias towards the British.

In September 1939, First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill began considering the possibility of blockading steel to the Germans. Norway, as a transport route for goods, started to look rather enticing as a potential zone for scuppering or at least delaying the delivery of iron. Sir Cecil Dormer, British minister at Oslo, did his best to assure the British Government that Norway’s sympathies, though technically neutral, rested firmly on the side of the Allies. He reported, ‘They favour the British cause, to a greater extent perhaps than in any other neutral country.’ The only real concern was whether the Norwegians would be prepared to break their neutrality and join a blockade of Germany.

Churchill was not keen to take a chance on Norwegian politics. Upon his arrival at the Admiralty it became clear in his mind that the ‘thousand-mile-long peninsula stretching from the mouth of the Baltic to the Arctic Circle had an immense strategic significance’. He wanted to sever Germany’s iron ore imports, in particular those coming through Narvik.

It was the constant diplomatic wrangles of the situation that caused him problems. Some of his senior staff favoured offensive action, even going as far as suggesting a division of destroyers be sent to Vestfjorden ‘as a convenient tool’. The political fury this would have caused the Norwegians would have been immense; they would have seen it as a direct challenge to their authority and neutrality. Understandably Churchill wavered at such ‘drastic operations’. He also turned down the idea of laying large-scale minefields, though he would consider the option of severing the Scandinavian Leads by placing mines there, ‘at some lonely spots on the coast, as far north as convenient’, basically at some place where the Norwegians might not notice them.

On 19 September, he set the matter before the War Cabinet, making it clear that heavy diplomatic pressure should be placed on Norway’s Government to prevent German iron ore traffic from traversing the Norwegian Leads. He added, almost threateningly, that if this could not be done he would be forced into taking serious counter-actions, such as mining Norwegian territorial waters to force German ships outside the zone of neutrality, making them fair game for British destroyers.

The Cabinet refused to give its permission for anything other than diplomatic measures and told Churchill it had information that the shipping of iron ore via Narvik by the Germans had virtually ceased since the outbreak of war and ‘that in view of Norway’s economic importance to Germany Berlin was unlikely to violate Norwegian neutrality, unless provoked by an Allied Intervention or an interference with the iron-ore supplies’. It was also reluctant to incur the wrath of other neutral countries and the USA, should it be seen to violate Norway’s rights.

Churchill was outraged:

My views on the naval strategic situation were already largely formed when I went to the Admiralty. The command of the Baltic was vital to the enemy. Scandinavian supplies, Swedish ore, and above all protection against Russian descents on the long, undefended coastline of Germany – in one place little more than a hundred miles from Berlin – made it imperative for the German Navy to dominate the Baltic.

Unfortunately various failures within the intelligence services, diplomatic services and among politicians meant the Cabinet did not realise just how much Hitler was coveting Norway and full control of the Swedish iron ore supplies – crippling his enemies just as Churchill wished to cripple him – as the war slipped quietly into its first year. Britain was still playing a gentleman’s game in the winter of 1939 and had failed to realise that Hitler was a cheat.

Churchill refused to be defeated by the Cabinet’s reluctance. By November the Royal Navy had drawn up plans of action to control the entrance to Narvik and force any German iron ore imports to Britain. It was a modern form of piracy. Churchill returned to the War Cabinet on 30 November with a report from the Ministry of Economic Warfare that stated that the war could be ended in a matter of months if the complete halt of Swedish iron ore to Germany was achieved. This would mean blockading more than just the imports through Narvik, but Churchill was positive that the coming winter would mean the Baltic would be closed with ice, forcing all German supply ships through the Leads. Strategic placing of minefields would force these ships out into international waters and the clutches of the Royal Navy.

Chief of the Imperial General Staff General Edmund Ironside was captivated by the idea, but he didn’t want to see just minefields being laid. He advocated a partial invasion of Norway. Of course this would upset the Germans, but they couldn’t do much about it until May when the icy waters unlocked. By which time, Ironside pointed out, the British could have developed a substantial defence as in ‘such a remote and forbidding country a very small force could hold up a large one’.

The War Cabinet remained unconvinced, but its utter refusal to consider blockades against the Germans was no longer so fixed. They didn’t know it, but it was now a race to see which force – German or British – would make its mind up first and seize Norway.

CHURCHILL’S BIG MISTAKE

The term ‘quisling’ has become synonymous with a traitor, but the original Vidkun Quisling saw himself as anything but when he approached Hitler in December 1939 to discuss what would occur should Britain invade neutral Norway. The former intelligence officer and defence minister had Nazi sympathies and hoped that a pro-German coup within Norway would enable him and his party, Nasjonal Samling (NS), which had always been on the fringes of Norwegian politics, to finally take centre stage. Quisling was ambitious, ruthless and narrow-minded. He impressed Hitler, who vowed that should Britain attempt to invade Norway the German response would be swift and brutal – even, he added sinisterly, if that meant a pre-emptive invasion. Other ministers in Hitler’s party were less convinced by Quisling. Much of the information he gave for the German invasion plans would later prove faulty or totally wrong. Quisling had an over-inflated sense of his own importance and abilities, but despite criticism from German ministers in Norway, he was accepted by the higher echelons of the Nazi regime.

When he spoke with Hitler in December and made subtle pushes for a Nazi invasion, Quisling had his own motives for gaining power in Norway and casting out his enemies in the government, who he saw as holding back his party. He said all the right things to spark the Führer’s anger. He stated that the Norwegian population was largely pro-British and would side with the Allies in the event of Norway being dragged into the war. He also said that it was his opinion that Britain had no intention of respecting Norwegian neutrality; in fact there was evidence (he claimed) that the Norwegian Government had secretly agreed to allow the Allies to occupy parts of southern Norway and threaten Germany’s northern flank. In contrast, the NS was prepared to work with Germany; they agreed with Hitler’s policies and had key people in the civil administration and the armed forces. Should the worst happen, Quisling was prepared to lead a coup which would open Norwegian doors for Germany before the British could get a foothold.

Quisling was exaggerating, but he appealed to Hitler’s strong sense of paranoia. While other German ministers were scowling and writing Quisling off as a braggart, Hitler was captivated. Even so, he made no direct moves, though plans were drawn up for the hypothetical invasion of Norway. It would be a clumsy move by Churchill that would prove the catalyst for the real invasion and Hitler developing a firm belief in Quisling’s views and opinions. This would prove fatal to many German soldiers and sailors.

In the early stages of the war, when Germany had been making decisive attacks against British merchant shipping with considerable success, Churchill’s attention had been drawn to a German ship named the Altmark. The Altmark was a tanker (auxiliary to the ill-fated Graf Spee) which had been serving as a prison ship for captured sailors from sunk British merchant ships. There was solid information to suggest as many as 300 British sailors were being held on the Altmark, arousing British fury and instigating a hunt for the elusive tanker. Knowing he would be unable to defend his vessel if he was engaged in a sea battle, the captain of the Altmark sailed out into the south Atlantic and hid there for two months in the hope the British would eventually give up.

In February 1940 this appeared to be just the case to Captain Langsdorff as he stood on the bridge of the Altmark. It had been a long two months hiding from the enemy, and his crew were more than ready to sail back to Germany with their prize of British sailors. Everything looked to be in their favour as they altered course and headed for home. The weather was with them as they sailed unmolested between Iceland and the Faroes and found themselves in Norwegian territorial waters on 14 February. That was when Captain Langsdorff’s luck evaporated. British aircraft spotted the ship they had been fruitlessly hunting for and word was rapidly sent back to Britain. Langsdorff was not entirely concerned. He was in neutral waters and any attack on his ship would require the British to break their pact of neutrality with Norway. He doubted even the pig-headed British would risk such a political catastrophe to recapture a few civilian sailors.

Langsdorff was woefully mistaken. Churchill had the bit between his teeth when it came to securing the prisoners from the Altmark and he saw Norwegian neutrality as no obstacle. ‘This ship is violating neutrality in carrying British prisoners of war to Germany,’ he told the First Sea Lord. ‘The Altmark must be regarded as an invaluable trophy.’

Just before midnight on 16 February 1940, the British destroyer Cossack, under orders from Churchill, sailed into Norwegian waters. Local naval vessels protested at the infringement, but Captain Philip Vian had his instructions and his sights were set on the German tanker. The Altmark slipped into Jösing Fjord, its retreat being guarded by two Norwegian gunboats trying to defend their country’s right to neutrality. They insisted that the tanker had been boarded for inspection and there had been no armaments or prisoners. Vian was unimpressed, but he quietly withdrew and sent this new information to Britain.

Churchill was irate when he heard the news. He intervened directly and sent a new order to Vian: ‘Unless Norwegian torpedo-boat undertakes to convoy Altmark to Bergen with a joint Anglo-Norwegian guard on board, and a joint escort, you should board Altmark, liberate the prisoners, and take possession of the ship pending further instructions.’

Vian needed no further prompting. He first boarded one of the torpedo ships to give his ultimatum, but again the Norwegians insisted that the Altmark had been properly searched and there was no call for any further action. Meanwhile Captain Langsdorff realised his time in the safety of the fjord was rapidly drawing to a close. In a desperate bid to escape the fjord he set the Altmark on a course to ram Vian’s ship. The attack was an utter disaster: the Altmark missed her target and grounded herself, giving Vian a prime opportunity to come alongside her and send across a boarding party. Langsdorff’s men resorted to hand-to-hand fighting to try to repel the British, but their hearts were not in it. In only a matter of moments four Germans were killed and another five wounded; those that remained either fled ashore or surrendered.

The Altmark came under British control and, with the Norwegians watching on anxiously, Vian ordered a search. He held no illusions about the thoroughness of the Norwegians’ previous searches and was not surprised when it was reported to him that his crew had found two pom-pom guns and two machine guns. So much for the Norwegian claims that she was unarmed.

The British prisoners were even easier to find. The Altmark was not designed to hold prisoners and the British had been stowed wherever there was an inch of space. They now emerged from the ship’s storerooms and even an unused oil-tank with the cry, ‘The Navy’s here!’

The attack made headline news across the world and Hitler was beside himself over the story. He was furious that there had been such poor resistance from both the Germans and the Norwegians. The British had sailed in with barely a challenge. The Germans had been humiliated and Hitler was now convinced that the Norwegians either couldn’t or wouldn’t defend their neutrality. Ironically the attack on the Altmark confirmed the phoney allegations Quisling had made, even if it was not the alleged precursor to invasion but a rescue operation.

Head of the Nazi Party Foreign Policy Office and Propaganda Section, Reichsleiter Alfred Rosenberg later wrote, ‘Downright stupid of Churchill. This confirms Quisling was right. I saw the Führer today and … there is nothing left of his determination to preserve Nordic neutrality.’

The day after the assault on the Altmark Hitler ordered the planning of Operation Weserübung, the invasion of Norway, to be stepped up a gear. As part of the reasoning for the attack, which would seriously reduce manpower for other operations, the need to protect the supply of Swedish iron ore to Germany was put forward. Under no circumstances could Britain be allowed to get into Norway first.

Britain stood by its decision to take the Altmark. The Times protested that the government had been right to board her considering the perfunctory searches the Norwegians had conducted. Lord Halifax confronted the Norwegian minister and argued that his countrymen had failed in their duty to preserve neutrality in Norwegian waters. In return the Norwegian minister handed a note to the Secretary of State protesting the assault and demanding that the prisoners be given back.

Norway was caught between two dangerous powers, both with an incentive to invade the Scandinavian country. Germany was making a huge fuss over the matter, the Nazi papers calling the rescue operation ‘an unexampled act of piracy’ on ‘a peaceful German merchantman’. They deplored the ‘brutal murder’ of German seamen and said it would leave a lasting stain on the British Navy. The Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung told its readers furiously, ‘We shall present the bill. As the British no longer command the sea they fall back on the territorial waters of a neutral country, and there attack a German merchantman, not like soldiers but like pirates.’ The Berliner Börsen-Zeitung added its own spin on the matter. ‘The shameful and cowardly way in which the British Government has behaved incorporates the spirit of the man who gave out as his motto on the first day of the war; “I hope I shall live to see Hitler suppressed.”’

While the British ranted over the misleading newsprint and the deplorable suppression of facts by the Nazi journalists, Hitler was wondering how lucky he could get. Churchill had played straight into his hand, giving him a prime reason for invading Norway and to justify Operation Weserübung. Not that he would have delayed the operation if he had not had such a good excuse, but it enabled him to do the thing he loved best – presenting the Nazis as the heroes, standing up to the oppression and devil-may-care attitude of the British. He couldn’t have been happier, especially knowing that Britain was firmly on the back foot despite its triumph over the Altmark. Churchill had no idea that he was about to be trumped when it came to occupying Norway.

OPERATION WILFRED

Life in neutral Norway was proceeding much as it had done before the war, with few civilians aware that their country was at the centre of a power play between two great warring nations. Even the government failed to truly understand how significant Norway was in the minds of the Allies and the Axis powers.

There had been warning signs; the German invasion of Poland had worried many Norwegians and had left an almost unanimous feeling of anger towards the Nazis. Quisling’s talk of having many supporters who would gladly side with the Germans in the conflict was all lies. Norway’s sympathies were firmly with the beleaguered Poland, but that didn’t mean it was going to do anything about the occupation. The prevailing feeling among the government and the Norwegian people was that this wasn’t their war and the best thing they could do was to stay neutral. This dogged determination for neutrality was so strong within the population and among the fighting forces that it would severely hamper Norway’s efforts to repel the Germans when they did finally invade.

More than one soldier when told to shoot at advancing German troops felt the need to remind his commanding officer that he had live bullets in his gun and could kill someone! Many admitted after the war to aiming over the German soldiers’ heads at first, unwilling to harm them, until it became apparent that neutrality was no defence against invasion.

Norway was blind to its future fate in those early days of the phoney war. After the invasion of Poland the government issued a declaration of neutrality, which was extended two days later to cover the war that France and Britain had just declared on Germany. There was an immediate freeze on all prices. Petrol, coal and certain imported goods were rationed. The public were reminded not to hoard, and advised that all would be well as long as they led cautious lifestyles. For a time the use of motorised vehicles was limited to preserve the petrol ration; people returned to using horses and there was a new popularity for bicycles.

Yet, for the most part, life continued as normal and few Norwegians gave much thought to the war happening in another part of Europe. In the first seven months of the war Norwegian newspapers carried stories of the loss of fifty-five Norwegian merchant vessels, resulting in the deaths of 393 sailors, almost all due to German attacks. But the incidents had occurred outside Norwegian neutral waters and the belief still prevailed that Norway had raised an impenetrable wall of neutrality around itself.

Even the government was lulled into this false sense of security. Mobilisation of troops to maintain the neutral borders and deter infringements was limited and largely pointless. The Royal Norwegian Navy (RNN) was supposed to be patrolling the waters and preventing problems, but it was not taken seriously by either the British or Germans. More symbolic than functional, the RNN had been reduced to insignificance between the wars and in 1939 a massive recommissioning operation had to take place just to have enough ships in service, many from the naval reserve. By April 1940, the RNN had 121 vessels in service, fifty-three of which were chartered auxiliaries consisting of requisitioned fishing vessels, whale-boats and small freighters. The auxiliaries were hastily armed with either a 76mm gun or a pair of machine guns and were intended purely for patrol or guard duties. They were not expected to engage an enemy in combat and certainly were not fit to do so. Another nine vessels were simply unarmed support ships.

More alarmingly, out of the fifty-nine actual Navy vessels nineteen had been launched just after the First World War and seventeen had been built before 1900; they were woefully inadequate for modern warfare. To serve on them the RNN had to draft staff officers from the coastguard stations, naval airbases and communication centres. A total of 5,200 men were ready for service by early 1940, but out of these only 1,398 had any pre-war experience.

From his vantage point in Britain, Churchill could see that Norway stood little chance should Germany decide to ignore its neutrality. He knew this because he was already planning something similar – Operation Wilfred.

Since September 1939, Churchill had been pestering the government to do something about Norway – his something was laying mines around the Norwegian Leads and landing troops in the country as a ‘prevention’ against German retaliation. ‘I called the actual mining operation “Wilfred”, because by itself it was so small and innocent,’ Churchill explained in reference to a popular Daily Mirror comic strip featuring the characters Pip, Squeak and Wilfred. Wilfred was a young rabbit who acted as the ‘child’ in the series, Pip the dog and Squeak the penguin being his adoptive parents. The long-running characters were favourites among the military; the three medals issued after the First World War to most British serviceman were nicknamed Pip, Squeak and Wilfred, and the RAF nicknamed its three post-First World War training craft after the characters. It is not surprising that Churchill, with his own brand of humour, enjoyed the idea of naming his mission after a small baby rabbit who could not even talk properly.

Operation Wilfred was touted by Churchill to his more cautious colleagues as a modest escalation of tension between the two nations. He did not consider that it might be too tentative, or even too late. Wilfred’s goal was to send two minelaying groups to the Norwegian coast, one to mine the approach to Narvik and scupper, at least until it could be cleared, the route for Swedish iron ore. The second minelaying group would block the Norwegian Leads off Stadlandet.

Concurrently with ‘Wilfred’ it was hoped an operation could be launched to release fluvial mines into the Rhine. The theory was that if enough could be released and allowed to drift they would catch a variety of shipping and also cause fear and confusion until the Germans could conclusively clear them. This operation was another favourite idea of Churchill’s, but the French were unenthusiastic as they believed it would lead to repercussions on their own aircraft industry, which was far from protected from attack.

However, it was repercussions that Churchill wanted. The twilight war had tired him and strained his nerves yet without conclusive action or results. Worse, he noted that morale in the French Army was faltering as the waiting increased. Churchill had deemed the French troops at their best just before the winter of 1939; after that the lack of any positive action had allowed infiltrations by Communist, and more troublingly, Fascist propaganda that had weakened the French fighting spirit. Churchill wanted action to spur his Allies back into a war mindset, but his tentative prods at the Germans to provoke a response were like prodding a rather unpleasant bear.

On 28 March, Churchill sat with the War Cabinet feeling a touch of satisfaction. He was about to brief it on the final arrangements of ‘Wilfred’ but was also determined to finalise details on what would occur when the German reprisals began. He was hopeful that German reactions would give the British a legitimate reason to land troops in Norway with the consent of the country’s government. He would not get the result he wanted that day, but on 1 April the War Cabinet endorsed a plan that became simply known as R4 and was viewed as the key to securing Norway.

OPERATION WESERÜBUNG

Hitler had two goals in mind with his Operation Weserübung plans: Weserübung Sud was the designation for the invasion of Denmark with the primary goal of capturing Copenhagen, while Weserübung Nord was the name for the invasion of Norway. The goals for the latter were to land large numbers of troops from warships at Narvik, Trondheim, Bergen and Kristiansand under the pretence that they were coming to help defend Norway against British infringements of their neutrality. Single companies of troops would be sent to capture the wireless stations at Egersund and Arendal, while the equivalent of two regiments would head for Oslo, securing Horten en route.

In the meantime air operations, including the first use of paratroopers in the conflict, would be conducted at Fornebu and Sola airports. The result would be the encirclement of southern Norway and the control of the country’s administration and military forces. Hitler expected the invasion to be a walk-over after the stagnant resistance given to the British when they seized the Altmark