Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

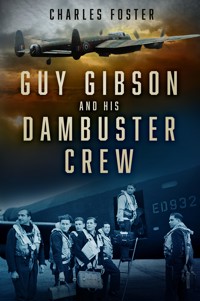

The Dams Raid is the RAF's most famous bombing operation of the Second World War, and Guy Gibson, who was in command, its most famous bomber pilot. Of the six men who made up his crew on the Dams Raid – two Canadians, an Australian and three Englishmen – only one had previously flown with him, but altogether the men had previously amassed more than 180 operations. Drawing on rare and unpublished sources and family archives, this new study is the first to fully detail their stories. It explores the previous connections between the seven men who would eventually fly on just one operation together and examines how their relationships developed in the months they spent in each other's company.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 368

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Actors playing Guy Gibson and his crew recreate the wartime Dams Raid photograph for the 1955 film, The Dam Busters. (News Chronicle, 31 May 1954)

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein, the publishers will be pleased to rectify any errors or omissions in any reprints or future editions.

Front cover images, top: RAF aircraft (Crown Copyright); bottom: Gibson and his crew pose for a picture as they set off on Operation Chastise. (© IWM CH 18005).

First published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Charles Foster, 2023

The right of Charles Foster to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 214 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

List of Illustrations

1 Introduction

2 Guy Gibson

3 John Pulford

4 Harlo Taerum

5 Robert Hutchison

6 Frederick Spafford

7 George Deering

8 Richard Trevor-Roper

9 The Crew Comes Together

10 The Plan to Attack the German Dams

11 Training for Operation Chastise

12 The Dams Raid: History is Written

13 Fame and Glory: After the Dams Raid

14 The Handover to Holden and the Trip to Africa

15 Gibson’s Trip to North America and Operation Garlic

16 Back to Work for Pulford and Trevor-Roper

17 The Man in the Ministry: Gibson Grounded

18 Back on Operations: Gibson’s Final Trip

19 The Dam Busters: The Book and the Film

Afterword

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

List of Illustrations

Frontispiece: Actors playing Guy Gibson and his crew recreate the wartime Dams Raid photograph for the 1955 film, The Dam Busters.

Page 17: Family home of the Strike family, Porthleven, Cornwall.

Page 36: Gibson, Hutchison and other aircrew in a group in 106 Squadron.

Page 42: The multi-page feature on 106 Squadron in the 12 December 1942 issue of Illustrated magazine.

Page 47: John Pulford.

Page 52: Telegram from Taerum to his family, announcing his sudden departure for the UK.

Page 54: Taerum and another airman in 50 Squadron.

Page 60: Hutchison and his fiancée, ‘Twink’ Brudenell.

Page 62: The daylight raid on Le Creusot, photographed by Hutchison.

Page 62: Reverse of the Le Creusot print, signed by Gibson, Hutchison and their crewmates.

Page 65: Fred Spafford.

Page 75: Deering after qualifying as a wireless operator/air gunner.

Page 76: Deering and crew in 103 Squadron.

Page 83: Trevor-Roper in mess dress at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich.

Page 92: Richard and Patricia Trevor-Roper on their wedding day.

Page 94: Trevor-Roper awarded the ‘Grog Gong’.

Page 95: Trevor-Roper in the crew of Sqn Ldr Peter Birch in 50 Squadron.

Page 131: Gibson and his crew pose for a picture as they set off on Operation Chastise.

Page 141: Debriefing after the raid.

Page 152: Eve Gibson in a photocall in her London flat.

Page 153: Instructions for the protocol to be followed for the Buckingham Palace investiture.

Page 156: Taerum and his fiancée outside Buckingham Palace.

Page 157: 617 Squadron group outside Buckingham Palace.

Page 159: Canadian contingent after the investiture.

Page 159: Australian contingent after the investiture.

Page 160: T.O.M. Sopwith presents Gibson with a silver model Lancaster.

Page 161: Party attendees after dinner at the Hungaria Restaurant.

Page 166: Gibson, Spafford, Hutchison, Deering and Taerum at Scampton.

Page 166: Trevor-Roper at Scampton with Shannon and Holden

Page 174: Gibson and crew in handover to Holden.

Page 174: Reverse of the handover print, signed by all aircrew.

Page 179: Gibson speaking at Calgary airfield.

Page 180: Photograph in Taerum family album, signed by Gibson.

Page 193: Article in Sunday Express, 5 December 1943.

Page 205: Gibson letter to Hutchison family, February 1944.

Page 234: Actors cast in the roles of Gibson and his crew pose with Michael Redgrave.

1

Introduction

In Michael Anderson’s 1955 film The Dam Busters (still regularly repeated on British television), there is nearly half an hour of running time before we first meet lead character Guy Gibson and his crew. It’s mid-March 1943 and their Lancaster aircraft is seen landing in daylight after a night-time raid on Germany. The pilot Gibson, played by Richard Todd, and his flight engineer John Pulford (Robert Shaw) exchange a line of jargon: ‘Rad shutters auto.’ ‘Rad shutters auto.’

The engines are switched off and Gibson then wipes his face with his silk scarf, shouting, ‘Brakes off’ through the cockpit window. Then we see seven young men clamber out, happy because they know that they have now finished their ‘tour’ of operations and can go on some much-anticipated leave. They board a small lorry which has bench seats, some puffing away at lit cigarettes, even though they are only a few feet from the fuel tanks and engines. An airman is holding the lead of Gibson’s dog, who has been waiting by the stand. The dog is released, runs up to its master and has its stomach tickled. ‘Good boy,’ it’s told, repeatedly. It’s going on its holidays and can chase rabbits. They are interrupted by a bit of joshing from the crew. ‘Come on, skipper, you’ll miss the bus,’ one shouts.

In the film, all seven men in this scene are given the real names of Gibson and the crew with whom he will fly later on the Dams Raid, and are played by actors who closely resembled them. However, this is where the film deviates from reality since, with one exception, the men who would fly on the Dams Raid on 16 May 1943 were not those who had been in his previous crew in 106 Squadron two months earlier. The only man who had flown with Gibson in 106 Squadron was his regular wireless operator, Robert Hutchison, but even he was not in the crew which bombed Stuttgart under Gibson’s command on the night of 11 March. He had finished his ‘tour’ of thirty-three operations a fortnight before and was on leave.

The next scene in the film opens with the officers from Gibson’s crew having a post-operation breakfast and engaged in a bit more repartee. They are making plans for a trip to London the next day, where they will take in a show before they disperse on leave. They will get a train after lunch. ‘You can count me in,’ says Gibson. But someone then comes up to Gibson with an order: he must report to Group HQ at 1100 the following day. He looks pensive. We cut to the next morning, and Gibson is driving up to Group HQ in his own car with his dog. He meets the Group Commanding Officer (CO) and is asked by him to undertake just ‘one more trip’ under conditions of great secrecy. Gibson will command the operation, in a new specially formed squadron, but it will mean putting off his leave. He can’t be told the target yet but it will mean low flying, at night: ‘You’ve got to be able to low fly at night until it’s second nature.’ He goes to another room with a different senior officer and starts the process of selecting who will join the new squadron and then discusses whether or not to bring his own crew with him. ‘No,’ he concludes, ‘they’ve had a hard tour. Must be sick of the sight of me by now. I’ll leave them alone.’

He drives back to the squadron’s base, and bumps into his rear gunner Richard Trevor-Roper (Brewster Mason) outside the mess. ‘Hurry up, skipper, you’ll miss the train,’ he says. Gibson replies that he won’t be joining them in London, he’s going to form a new squadron. ‘Before your leave?’ asks Trevor-Roper, incredulous.

‘You tell the boys, will you, Trevor?’ says Gibson and walks off.

He’s then seen in his bedroom packing a bag, only to be interrupted by Trevor-Roper and another crewmate, Harlo Taerum (Brian Nissen, a British actor putting on a Canadian accent). ‘This new squadron. Are you going to fly with it?’ asks Trevor-Roper.

‘Of course,’ says Gibson. Taerum asks him if he isn’t going to need a crew, to which he replies saying he will get one.

‘Do you want to get rid of us?’ he’s asked.

‘I didn’t say that,’ he says.

‘Well, we’ve just held a committee meeting,’ says Taerum, ‘and it’s the general opinion that it’s not safe to let you fly about with a lot of new people who don’t know how crazy you are. It’s the general opinion that you will need us to look after you.’

‘Well, if that’s what you want to do, all right,’ Gibson replies. ‘But I think you are the crazy ones, the whole bunch of you.’ The camera zooms in to show his face; he’s obviously pleased with their loyalty. The whole scene is a typical passage of dialogue from the pen of scriptwriter R.C. Sherriff, disguising wartime emotional attachment with semi-humorous banter. And, of course, it’s completely fictional.

Thus is the myth perpetuated that Gibson and his old crew moved from his previous posting, commanding 106 Squadron at RAF Syerston, to his new job, setting up what would soon be called 617 Squadron at RAF Scampton. This myth was created by just one line in Paul Brickhill’s 1951 book The Dam Busters (the source for Sherriff’s script), which simply says that Gibson had brought his own crew to Scampton.1 This is a line that Brickhill obviously never checked. The first chapter of Gibson’s own book, Enemy Coast Ahead, written in 1944 but not published until 1946, eighteen months after his death on operations, is slightly more nuanced on the subject.2 In the course of its eight pages, readers are introduced to all six men in his crew as they fly towards the German dams on the night of 16 May 1943, but for how long Gibson had known them, with the exception of Hutchison, is not spelt out.

There has been some debate about whether Gibson wrote the text of Enemy Coast Ahead himself, or whether it was ghost-written by a professional writer. The majority of the manuscript probably came directly from him: he was given use of a recording machine and typing facilities while on a desk job in the Air Ministry in early 1944, and the breezy style sounds like the authentic voice of a 25-year-old bomber pilot with plenty to say. That said, small amounts of material from two separate 1943 articles published in an American magazine and the Sunday Express, and almost certainly ghost-written by professional writers, appear in the book almost word for word. We don’t know now how much of this first chapter was written by Gibson, but it’s obvious that the text never went through the hands of a sub-editor or fact-checker.

In the course of this opening chapter, Gibson says a few words about each of the men in his Dams Raid crew, mostly using nicknames. ‘Spam’, the bomb aimer Flg Off Fred Spafford, was a ‘grand guy’ from Melbourne, Australia, and ‘many were the parties we had together; in his bombing he held the squadron record’. He had done about forty trips and ‘used to fly with one of the crack pilots in 50 Squadron’. ‘Terry’, the navigator Flg Off Harlo Taerum, was a ‘well-educated’ Canadian from Calgary and probably the most efficient navigator in the squadron. He had flown on about thirty-five operations. ‘Trev’, Flt Lt Algernon Trevor-Roper, the rear gunner, came from ‘a pretty good family and all that sort of thing’, had been to Eton and Oxford and had done sixty-five trips. He was one of the real squadron characters who would go out with the boys and get completely plastered, but was always up on time in the morning. ‘Hutch’, the wireless operator Flt Lt Robert Hutchison, who ‘had flown with me on about 40 raids and had never turned a hair’ was one of those ‘grand little Englishmen who have the guts of a horse’.

All these were officers, but the remaining two had been non-commissioned officers (NCOs) when they first joined up with Gibson, which might explain why he seemed to know so little about them. ‘In the front turret was Jim Deering of Toronto, Canada, and he was on his first bombing raid. He was pretty green, but one of our crack gunners had suddenly gone ill and there was nobody else for me to take.’ George Deering’s commission as a Pilot Officer had actually come through in mid-April, but the flight engineer, Sgt John Pulford, was an NCO. He is merely described by Gibson as a Londoner, and a ‘sincere and plodding type’.

There are so many errors in this account of these six summaries that it’s almost tedious to list them all. All the figures for numbers of previous operations are wrong. In real life, Spafford had thirty-two, Taerum thirty-two, Trevor-Roper fifty-one and Hutchison thirty-three (eighteen with Gibson). Contrary to Gibson’s description, George (not Jim) Deering was not at all ‘green’: he had an impressive record of thirty-two operations in 103 Squadron before being sent on training duties, where he flew on two more. Also, it was not a last-minute decision to use him as the front gunner, replacing someone who had gone ill: Deering had first flown with Gibson on 4 April and had been on nearly all the crew’s training flights, and nobody in the crew had fallen ill. Pulford’s operational career isn’t mentioned, but he had racked up thirteen operations in the three months’ experience he had built up in 97 Squadron. When it comes to geography, Spafford was from Adelaide, rather than Melbourne, and Pulford from Hull, not London. There are further mistakes in the description of Trevor-Roper. His first names were Richard Dacre, not Algernon. This error has persisted since, to the annoyance of his family, and has been repeated in many books and on countless websites. Also, he was educated at Wellington and the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich, rather than Eton and Oxford.

So these were the seven men who flew in Lancaster AJ-G on the night of the Dams Raid. Five of them met Gibson for the first time in March or April 1943 and this was the first and last time that all seven would fly together on an operation. Sixteen months later, on 19 September 1944, Gibson and his navigator were both killed when the Mosquito aircraft they were in crashed in the Netherlands in still-uncertain circumstances while co-ordinating a raid. Gibson had left the completed manuscript of Enemy Coast Ahead behind in London, with five of the six names above listed in the book’s appendix, the Roll of Honour. They appear on page 14 of the first edition in the following manner:

MY CREWMissing, night September 15, 1943

F/O Spafford

‘Spam’

F/O Taerum

‘Terry’

F/Lt Hutchison

‘Hutch’

P/O Deering

‘Tony’

F/Lt Trevor-Roper

‘Trev’

Even here there are more errors. It was the first four who died on 15 September 1943, killed flying on a bombing operation with Gibson’s successor as Commanding Officer of 617 Squadron, Wg Cdr George Holden DFC. By this time, Trevor-Roper was no longer with the squadron, and was not killed in action until 31 March 1944. And to compound Gibson’s lack of knowledge about Deering, he is given another nickname, ‘Tony’.

John Pulford isn’t even ascribed the dignity of being present on Gibson’s list. In fact, he served in 617 Squadron the longest of them all, having joined Sqn Ldr Bill Suggitt’s crew in the autumn of 1943. The whole Suggitt crew died on 13 February 1944 in a crash following an attack on the Anthéor Railway Viaduct.

In this first chapter, Gibson does give us a few snippets of the private lives of the crew, and to his credit these would seem to be pretty accurate. We are told that Trevor-Roper’s wife was living in Skegness, and was about to ‘produce a baby within the next few days’. (His son was indeed born in the seaside town on 15 June.) Two more had girlfriends: Hutchison’s was a ‘girl in Boston’ (the Lincolnshire Boston, that is). Taerum was ‘in love with a very nice girl, a member of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) from Ireland called Pat’. He doesn’t, however, tell us any more about Pulford, Deering or Spafford, although at least one of these also had a fiancée.

These six men – all of whom were decorated for their work on the Dams Raid – therefore have this mythic status of being ‘Guy Gibson’s crew’. This book explores the connections between them and their pilot and tells their collective story for the first time. We will trace the individual histories of all seven from birthplaces in exotic locations ranging from Milo, Canada, and Simla, India, to the Isle of Wight and Hull, document how they joined the air forces of three different countries, and examine the six weeks in the spring of 1943 during which they flew on their one and only operation together. And we will see what they all did after their participation in the historic raid that brought them enduring fame in the few months they had left on earth.

How This Book is Structured

As mentioned previously, the seven men did not all meet together until April 1943. Therefore, in the next seven chapters each of their lives before that date is examined individually, and further chapters follow on their first meeting, the background and training for the Dams Raid, the raid itself and the public recognition of the part each played. Thereafter, their paths began to diverge and so their individual stories are traced once more. Finally, after their deaths, all of which fell in one twelve-month period, we see how their service was immortalised in print and on screen.

1 Paul Brickhill, The Dam Busters (Evans, 1951), p.51.

2 Guy Gibson, Enemy Coast Ahead (Michael Joseph, 1946), pp.19–21.

2

Guy Gibson

Pilot

Located in a row of houses on a cliff-top road in the small Cornish fishing village of Porthleven is a fine three-storey dwelling built in Victorian times. Soon after the turn of the twentieth century this became the home of an upwardly mobile master mariner and businessman by the name of Edward Strike, his wife Emily and their seven children. The family had moved there from a small cottage in the village, as their situation had improved. To demonstrate their enhanced position in society, Mrs Strike liked to make sure her daughters acted as young ladies. They were always impeccably dressed and were in trouble if they didn’t wear white gloves when going down to the village. As if to emphasise the distance they had come from their more modest birthplace, the four youngest girls were sent to a Catholic convent in Belgium for part of their education, even though the family were Methodists.3

In the summer of 1913, when the Strikes’ fourth child Leonora Mary (known as Nora) was 19, a handsome bachelor called Alexander James Gibson (known throughout his life as A.J.) arrived in Porthleven on leave from his job in India. He had been born in 1876 to a Scottish father living in Russia with a local wife and was sent home to Edinburgh Academy for his schooling. He then prepared for entry to the Indian Forest Service (IFS), which had been set up in 1843 by an ancestor of the same name, studying at the Royal Indian Engineering College in Staines, Middlesex. He took up his first job in the Kangra division of the Punjab in 1898.4

Family home of the Strike family, Porthleven, Cornwall. (Author photograph)

Young men joining the IFS were expected to remain single but as they rose through the ranks they were allowed to contemplate marriage, and at this point in their lives many used the opportunity of being on home leave for several months to look for a bride. Gibson fitted the pattern, and when he attended a concert in the village one evening, he was immediately struck by a singer in the choir. This good-looking girl was Nora, and she had a fine contralto voice. Later he would discover that she was also a talented artist, and he then decided that she would be a fine match.

He sought her out, and they soon began a very chaste relationship. At first, Mr and Mrs Strike were horrified that their teenage daughter was set on marrying a man so much older than herself. Although he seemed civil enough, there was an air of mystery about him. Nora, however, was determined and her parents relented, and on 2 December 1913 they put on an extravagant wedding for the couple in the village’s Wesleyan Chapel.

A.J. and Nora set off for a honeymoon in Paris before sailing for India. It was in France that Nora discovered there was another side to her new husband. He insisted on taking her to a brothel where he used the services of a prostitute so that she could see what was expected of her in married life. This man-of-the-world attitude was an introduction to what was to follow in her new home, thousands of miles from Cornwall. When back in his own adopted country, A.J. would prove to behave somewhat differently than in England.

Their new base was the town of Simla, in the Himalayan foothills, the summer capital of the government. Nora enjoyed the retinue of servants which came along with A.J.’s social status: cooks, bearers, uniformed orderlies and an ayah for the children who followed in quick order. Alexander Edward Charles (‘Alick’) was born in June 1915, Joan Lemon in August 1916 and, two years later, Guy Penrose on 12 August 1918. Guy was the name of a family friend; Penrose was derived from the well-known manor house near Porthleven.

Although A.J. expected Nora to put up with his own extra-marital liaisons, he was not happy when she turned the tables. A series of handsome young officers began to pay attention to her and there was tension between the couple. This didn’t impact on the children’s behaviour, brought up as they were largely by the servants. For them it was a childhood full of happy times and exotic experiences.

The Gibson children first set foot in England in the summer of 1922, the year when Guy reached his fourth birthday. They were brought back to Cornwall on holiday by their mother and stayed in their grandparents’ house in Porthleven, having many encounters with cousins and other relatives while exploring the delights of a traditional Cornish seaside holiday. Meanwhile, back in Simla, A.J. had been promoted to a more senior job shortly before his family took their holiday and was even more absent than before when they returned home in the autumn. Tension grew as the couple become more detached from each other, and as time went by it became obvious that the marriage would not last. Alick was now old enough (by the standards of the time) to be enrolled in a British boarding school so Nora decided that she would bring him to England, along with the other two children.

It was not a good trip back from Bombay. The weather was poor, and the three children squabbled. When they landed in England, Nora quickly found herself in difficult financial circumstances, since A.J. had not provided them with much in the way of support. Unwilling to call on her own family, Nora and the three children eventually moved into a suite at the Queen’s Hotel in Penzance, and Nora sent Alick and Guy as day pupils to a local prep school, the West Cornwall College. She obviously discounted the need to get Joan educated, an attitude still all too common in the 1920s. There was more: she had got used to the heavy drinking culture while socialising in India, and she carried on the habit after having returned home. She also began an ‘ill-concealed affair’.5 Only just 30 herself, she was already exhibiting the behavioural tendencies which were to prove so problematic for the rest of her life.

Alick went to Earl’s Avenue School (later renamed St George’s School) in Folkestone as a boarder and in 1926 Guy joined him. During school holidays, the children lived a nomadic life, partly spent with their mother, partly with their grandparents and other relatives. Porthleven was an idyllic place for small children and it instilled in Guy a love for the seaside and small boats that lasted into adulthood. Sporadic episodes of bad and/or dangerous behaviour by their mother marred the school holidays. On one occasion, Nora decided to drive the boys back from Cornwall to school in Folkestone. By that time, she had moved to London so she also had Joan, who was living with her, in the car. Near Amesbury in Wiltshire, she was driving too fast, both her front tyres blew out and the car flew off the road and down an embankment. Nora suffered broken ribs, but the children were miraculously unhurt and had to continue their journey by train.

Meanwhile A.J. had returned to the UK, taking up a job with the Department for Scientific and Industrial Research in London, where he also rented a flat. He saw the children occasionally, but relations were inevitably strained. He did, however, pay the fees for Alick to move on to second-level education, so he was enrolled in St Edward’s School in Oxford at the beginning of the Easter term in January 1930. Guy would follow him there, aged just 14, in September 1932.

The 1920s and 1930s were a buoyant period for public schools, growing both in the numbers of schools and the pupils who attended them, as an expanding middle class knew that the education they provided was ‘the route to esteem and success’.6 St Edward’s School, founded in 1863, was typical of public schools of the era, with a headmaster (known as the Warden), who was both High Church Anglican and a prolific user of corporal punishment. This was Rev. Henry Kendall, still in the first decade of his leadership of the school but who would provide the inspiration and astute financial sense which played a crucial role in cementing its status and providing for its future in the years that followed.

Both boys were in Cowell’s House under the house mastership of A.F. (‘Freddie’) Yorke, who taught science. Widely regarded as a humane and thoughtful man (at least by the standards of the time) he came to occupy a quasi-paternal role in the life of the Gibson boys, shielding them from newspaper reports concerning their mother’s escapades and helping with accommodation over the holidays. A.J. had now bought a house in Saundersfoot in Pembrokeshire, near that of a lady friend who had already borne him a child. His other children would occasionally stay there and, even though relations with his father were still difficult, Guy found the area so congenial that in the future he would spend many holidays there. Nora’s sister Gwennie and her husband, also based in South Wales, helped out with accommodation and Guy developed a special bond with them.

Guy Gibson’s time at St Edward’s was not particularly distinguished, either academically or on the sports field. ‘Corps’ (army training) was compulsory one afternoon a week, as were games on the other days. He played rugby to a reasonable level, making the Second XV as scrum half, a decision-making position that perhaps predicted that he would reach a commanding role in a service career. But he was only a ‘house’ prefect, so his opportunities for leadership were limited.

However, it was at school that he first became interested in flying, one of many young men and women of the time who found it fascinating. This was the era of the Schneider Trophy and the Flying Flea, of Amy Johnson and Jim Mollison, whose exploits were well covered in the national press. A schoolmaster, Maitland Emmett, had a Bristol fighter aircraft which he had bought for £15 and kept in a field near the school, and this may have sparked his interest. Small wonder that an 18-year-old would want to explore how to take up flying as a career.

Gibson decided that he would like to be a test pilot and with this in mind wrote for advice to Captain Joseph ‘Mutt’ Summers, chief test pilot at Vickers-Armstrongs. About seven years later they would meet for the first time. Summers told him that the best way of getting trained would be to join the RAF. Gibson decided to do so, but his first application was refused – apparently, he was too short – so he tried again a few months later. This time he was accepted, so he must have grown a little in the intervening period. Not long after his eighteenth birthday, in November 1936, he was sent on the No. 6 Flying Training Course at Yatesbury in Wiltshire. This was a civilian course, involving both ground drills and flying and lasting just a few weeks, run under the RAF Expansion Scheme. Men who qualified were then recruited directly into the RAF and given a short service commission, so by 31 January 1937 Gibson was an acting Pilot Officer. After a week’s leave, and this time in uniform, it was back to Wiltshire and No. 6 Flying Training School in Netheravon. On 24 May 1937, after more training in Hind and Audax biplanes, forty-two new pilots were awarded their wings. Their training finished on 31 August, but it had not been without hazard. Two trainee pilots were killed when their Audax crashed near Sutton Bridge on 4 August, a salutary warning of the perils of flying.

Gibson’s first posting was to 83 (Bomber) Squadron at RAF Turnhouse in Scotland, in September 1937. He was assigned Plt Off Anthony (‘Oscar’) Bridgman as a mentor and was taken aloft by him shortly after arrival. They ended up flying low over the area, including a ‘beat-up’ pass near a sanatorium that had patients diving for cover. Gibson enjoyed the experience and delighted in retelling the experience many times over the ensuing months. The story, as they say, gained much in the telling.

Six months passed with not much happening except yet more training. Then, in March 1938, 83 Squadron was transferred a couple of hundred miles south, to the newly built RAF station at Scampton, Lincolnshire. The location was much more to Gibson’s taste. He was much closer to his brother Alick’s new house in Rugby and he would visit there often. Alick, who had an engineering job in the town, had started a relationship with a local young woman, Ruth Harris, and they became engaged in August that year. Guy meanwhile went out with several other women, but none for any significant length of time. With potential girlfriends as well as with others in his life, he was gaining a reputation for impetuosity and for wanting to be the centre of attention. As would be the pattern throughout his service career, this behaviour would be welcomed by some and shunned by others.

Gibson’s time in 83 Squadron lasted three years, from September 1937 to September 1940, and Gibson devotes nearly half of the text of Enemy Coast Ahead to the third year, the first of the war. He began this twelve-month period as a 21-year-old Pilot Officer, estranged from both his parents with no steady girlfriend. He would end it as an experienced Flying Officer with a full tour of thirty-seven completed operations and engaged to be married.

In September 1939, the atmosphere among the young members of the Officers’ Mess at Scampton was a ‘settled and socially homogenous community’7 – very similar to that of the middle ranks of a house at a public school: boys in their third and fourth years who are no longer ‘fags’ but don’t have the responsibility of being prefects. Gibson writes about several of the characters: Oscar Bridgman, now his flight commander, a ‘tremendous character’ with a quick temper. Jack Kynoch, a tall, swimming champion, with not too much sense of humour. Mulligan and Ross, two Australian boys who did nearly everything together. Ian Haydon, married to a ‘very pretty’ girl called Dell, to whom he ‘shot back’ to Lincoln to be with her every night that he could manage. Someone called just ‘Silvo’ – ‘What a chap!’ And Pitcairn-Hill, a straight-faced and true Scot who had played rugger for the RAF. ‘We were proud of ourselves we boys of A Flight, because we were always putting it across B both in flying and drunken parties.’8

Gibson doesn’t, of course, write about how he fitted into this boisterous crowd. He was now more than two years into his RAF service, past the initial time allotted to his short service commission that had been renewed due to the widely expected outbreak of war. Seen as someone who liked to be the centre of attention, challenging, sometimes thoughtless, he also had developed a tendency to criticise and call out ground crew, many of whom had come to dislike him vehemently.

By this time, the squadron was flying in Handley Page Hampdens, a twin-engined medium bomber. With enclosed cockpits and a four-man crew, they were among the most technologically advanced aircraft in the service. The crew consisted of a pilot, a navigator/observer, a wireless operator/mid-upper gunner and a rear gunner. It would be another three years before the four-engine heavy bombers would come into operation, although production on these had started in the period after the Munich crisis in 1938.

Gibson was on leave, sailing off the Pembrokeshire coast, when the Germans threatened to invade Poland and it became obvious that war would soon come. Finally, on 31 August, his leave was interrupted. The day’s events form the second chapter of Enemy Coast Ahead: a telegram arrived, Gibson’s leave was cancelled and he had to return to his unit immediately. His friend Freddie Bilbey offered him a lift in his Alvis, and the pair set off, fortified by beer and steak in Carmarthen, driving very fast and overtaking anything going too slowly. Freddie dropped Gibson off in Oxford, where they had more beer and a bottle of ‘excellent 1938 Burgundy’, and he completed the journey to Lincoln by train, arriving at Scampton at 4 a.m. There followed two days of intense activity, punctuated by the squadron gathering around the wireless to listen to the latest news. On Sunday, 3 September, Neville Chamberlain made his fateful broadcast to the nation. As his voice faded away, Sqn Ldr Leonard Snaith, the squadron’s Commanding Officer (another man who had also played rugger for the RAF), broke the silence. ‘Now’s your chance to be a hero, Gibbo,’ he said. So, a few hours later, Plt Off G.P. Gibson walked up to 83 Squadron’s Hampden L4070, climbed in and went to war.

Snaith led a section of six Hampdens from 83 Squadron to attack German warships in the Schilling Roads and at Wilhelmshaven, on the North Sea coast. The weather was awful, and navigation proved very difficult. Eventually, the raid was abandoned and the aircraft returned to base, although landing at night – which Gibson had never done before – proved difficult. It might have been Gibson’s first operation, but it would prove to be his last for four months, and this period would become known as the ‘Phoney War’.

Gibson had been due to be the best man at his brother Alick’s wedding to Ruth Harris two days after the war started. Originally scheduled for November, the date had been brought forward because of uncertainty as to when Alick’s regiment would be posted, and the ceremony had been booked in Rugby register office. Gibson was resigned to missing the event, but on his way into the mess the morning after the unsuccessful raid, he bent down to pat the station commander’s black Labrador. The dog bit him hard on the hand, and he needed five stitches. Given sick leave and with his arm in a sling, he set off for Rugby straight away, where he enjoyed a drunken ceremony in a hotel bar swollen by other revellers.

When he returned to Scampton, he found that preparations were being made for the squadron to move to Ringway in Manchester (now the city’s commercial airport), in case the Germans started bombing well-known Bomber Command bases. The panic only lasted ten days, they returned to Scampton and he would stay there most of the next year until he completed his first tour of operations in September 1940.

Despite the outset of war, there was no action at first. But there was more intensive training, punctuated by the occasional leave, which he mainly spent with Alick and Ruth. One night in early December, he went with them to see a revue called ‘Come Out to Play’, starring Jessie Matthews, in the New Hippodrome theatre in Coventry. In the chorus was a 28-year-old dancer called Eve Moore, and Gibson was immediately smitten.

His behaviour thereafter was that of the traditional stage-door Johnny. He ‘went round’ after the show, sending a message up to her dressing room, then taking her for supper and plying her with drinks. He then insisted that they meet again for lunch the next day, and he went to the show once more that evening. Another supper followed: ‘I think you are a humdinger, and I want to be with you as much as possible,’ was his clincher of a chat-up line.9

Performances of her revue were suspended for Christmas, so Eve returned home to her family in Penarth, just outside Cardiff. Having wangled a flight to the nearby airfield of St Athan, ostensibly a ferry trip in a Hampden to have new equipment installed, Gibson turned up unannounced on her doorstep, very keen to pursue their relationship. A few days later, he was back in Penarth on the night when his mother, Nora Gibson, suffered a terrible accident after standing too close to an electric fire in her bedroom in London and her dress going up in flames. Taken to hospital, she died of burns and shock on Christmas Eve. It’s not known when or how Gibson found out the news. He hadn’t seen his mother since he’d left school, and he heard little from his father. None of the three Gibson children attended the funeral in Golders Green: Alick and Guy by choice, it seems, and Joan was given the wrong time by their father, A.J. However, the trust that had been settled on the children reverted to them and each received a sum of money. A.J. was quick to contact his son Guy, pleading poverty and asking for the money to be returned to him.10

Part of the squadron moved to RAF Lossiemouth in February 1940 to assist Coastal Command in ‘sweeps’ of the North Sea, searching for enemy submarines. Gibson flew on two of these, his first operational flying for five months. His section almost caused a major incident when it wrongly identified two Royal Navy submarines and tried to bomb them. Fortunately, the bombs missed and exploded harmlessly. On the journey north by train, Gibson had managed to see Eve in a new performance of ‘Come Out to Play’ in Glasgow.

It was not long after the return to Scampton that the Phoney War stopped. The Germans invaded Norway and Denmark on 9 April, leading to attempts by the RAF to lay enormous minefields between Jutland and the Danish islands in order to disrupt the German navy. These ‘gardening’ operations were interspersed with ‘ploughing’ (actual bombing of targets in Germany), and Gibson flew on ten of these in April and May. The end of this period coincided with the invasions of Belgium, the Netherlands and France and then the replacement of Chamberlain and the Conservatives by Churchill and a coalition government: the ‘Ten Days in May’ seen as a major turning point in the war by historians ever since. ‘The Finest Hour’ was soon to follow the ‘Gathering Storm’, as the remnants of the British Expeditionary Force converged on the beaches of Dunkirk to await evacuation back to England.

Gibson survived a collision with a barrage balloon cable on a trip to bomb Hamburg on 17 May, and a fortnight or so later he was on a week’s scheduled leave with Eve in Brighton as the Dunkirk rescue operations began. It emerged later that Alick and his Warwickshire Regiment were one of those units to make it safely home.

Returning to Scampton, he then embarked on what would be so far the most strenuous part of his war, with sixteen operations in the months of July, August and September. Many of the squadron members mentioned earlier had been killed by the time he went on his final trip in 83 Squadron, an attack on Berlin on 23 September. Those lost included Pitcairn-Hill, the Aussie pair of Ross and Mulligan, Haydon and ‘Silvo’, whose full name turned out to be Flg Off Kenneth Sylvester. To cap it all, his friend Oscar Bridgman failed to return from the Berlin operation, and this had a profound effect on Gibson, although it would later emerge that Bridgman was in fact a prisoner of war. Gibson had flown on thirty-seven operations, thirty-four in the previous five months.

The overall cost had been mighty. Fifty men had been lost from 83 Squadron, only twelve of whom were prisoners, but Gibson had been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) and, more importantly for his subsequent career, he had been noticed. Air Vice Marshal Arthur Harris, who will crop up later in this chapter, was the Air Officer Commanding (AOC) of 5 Group at this time. Gibson may only have been a relatively junior officer, but Harris wrote just eighteen months later that he was ‘without question the most full-out fighting pilot in the whole of 5 Group when I had it’.11

Gibson was posted to RAF Cottesmore as an instructor in 14 Operational Training Unit, but he hardly had time to unpack his bags. He went down to Wales to see Eve and proposed to her under a tree while walking home on a wet night. The engagement was announced on 8 October.

On his return he found out he was on the move. There was a chronic shortage of experienced pilots for the RAF’s night fighters, run by 12 Group, and its Commanding Officer, Air Vice Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, had sent out a request for help. Harris explained his response in the same correspondence quoted above. He had chosen ‘a hand-picked bunch of which Gibson is the best’ and Gibson had agreed to give up his training period and take on something more interesting. Harris had struck a remarkable bargain: ‘when [Gibson] had done his stuff on night-fighters’ he would give him ‘the best command within my power’.

This deal would take some sixteen months to play out. In the meantime, Gibson set off for RAF Digby to join 29 Squadron as a flight commander along with a promotion to Flight Lieutenant. He arrived there on 13 November to a somewhat hostile reception, as he was a bomber pilot promoted above a bunch of ‘glamour boys’ in a fighter squadron. The atmosphere thawed quite quickly, however, and eight days after his arrival he was allowed to fly a Blenheim to Cardiff in order to get married.

In wartime, the time between engagement and ceremony was often short, and the Gibson–Moore wedding was no exception. The Moore family liked to do things properly (after all, Eve was marrying a public-school-educated officer). So they arranged a traditional church ceremony to take place on 23 November in All Saints Church in Penarth, with a reception afterwards in the Esplanade Hotel. Eve told her father on the way to the wedding that she thought Guy would be famous one day. His reply was that she shouldn’t be too ambitious. The only Gibson relatives there were his Aunt Gwennie, her husband John and another cousin, Leonora. Alick and Ruth were stuck in Northern Ireland with Alick’s regiment and a baby son. His sister Joan was also unable to attend. Whether A.J. was even invited is not clear. He had recently remarried, to a woman thirty years his junior.