Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

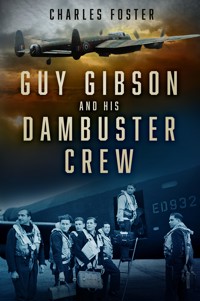

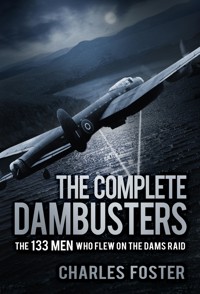

On 16 May 1943, nineteen Lancaster aircraft from the RAF's 617 Squadron set off to attack the great dams in the industrial heart of Germany. Flying at a height of 60ft, they dropped a series of bombs which bounced across the water and destroyed two of their targets, thereby creating a legend. The one-off operation combined an audacious method of attack, technically brilliant flying and visually spectacular results. But while the story of Operation Chastise is well known, most of the 133 'Dambusters' who took part in the Dams Raid have until now been just names on a list. They came from all parts of the UK and the Commonwealth and beyond, and each of them was someone's son or brother, someone's husband or father. This is the first book to present their individual stories and celebrate their skill, heroism and, for many, sacrifice.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 597

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The CompleteDambusters

The 133 men who flewon the Dams Raid

First published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire GL5 2QG

www.historypress.co.uk

© Charles Foster 2018

The right of Charles Foster to be identified as author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8848 3

Design + typesetting by Charles Foster

Further information about this title at www.completedambusters.com

Printed and bound in Turkey by Imak

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

For M.J.M.F.

1924–1987

Contents

Chapter 1: Introduction

A note on RAF structures and training

Chapter 2: Planning the raid

Chapter 3: Selecting the aircrew

Chapter 4: Finalising the crews

Crew 1: Wg Cdr G.P. Gibson DSO and Bar, DFC and Bar

Crew 2: Flt Lt J.V. Hopgood DFC and Bar

Crew 3: Flt Lt H.B. Martin DFC

Crew 4: Sqn Ldr H.M. Young DFC and Bar

Crew 5: Flt Lt D.J.H. Maltby DFC

Crew 6: Flt Lt D.J. Shannon DFC

Crew 7: Sqn Ldr H.E. Maudslay DFC

Crew 8: Flt Lt W. Astell DFC

Crew 9: Plt Off L.G. Knight

Crew 10: Flt Lt R.N.G. Barlow DFC

Crew 11: Flt Lt J.L. Munro

Crew 12: Plt Off V.W. Byers

Crew 13: Plt Off G. Rice

Crew 14: Flt Lt J.C. McCarthy DFC

Crew 15: Plt Off W. Ottley DFC

Crew 16: Plt Off L.J. Burpee DFM

Crew 17: Flt Sgt K.W. Brown

Crew 18: Flt Sgt W.C. Townsend DFM

Crew 19: Flt Sgt C.T. Anderson

Chapter 5: Training for the raid

Chapter 6: Operation Chastise

Wave One: Attacks on the Möhne and Eder Dams

Wave Two: Attacks on the Sorpe Dam

Wave Three: Mobile reserve

Chapter 7: The men who flew on the Dams Raid

CREW 1

AJ-G: First aircraft to attack the Möhne Dam. Returned safely.

Pilot: Wg Cdr G.P. Gibson DSO and Bar, DFC and Bar

Flight engineer: Sgt J. Pulford

Navigator: Plt Off H.T. Taerum

Wireless operator: Flt Lt R.E.G. Hutchison DFC

Bomb aimer: Plt Off F.M. Spafford DFM

Front gunner: Flt Sgt G.A. Deering

Rear gunner: Flt Lt R.D. Trevor-Roper DFM

CREW 2

AJ-M: Second aircraft to attack the Möhne Dam. Shot down.

Pilot: Flt Lt J.V. Hopgood DFC and Bar

Flight engineer: Sgt C.C. Brennan

Navigator: Flg Off K. Earnshaw

Wireless operator: Sgt J.W. Minchin

Bomb aimer: Flt Sgt J.W. Fraser

Front gunner: Plt Off G.H.F.G. Gregory DFM

Rear gunner: Plt Off A.F. Burcher DFM

CREW 3

AJ-P: Third aircraft to attack the Möhne Dam. Returned safely.

Pilot: Flt Lt H.B. Martin DFC

Flight engineer: Plt Off I. Whittaker

Navigator: Flt Lt J.F. Leggo DFC

Wireless operator: Flg Off L. Chambers

Bomb aimer: Flt Lt R.C. Hay DFC

Front gunner: Plt Off B.T. Foxlee DFM

Rear gunner: Flt Sgt T.D. Simpson

CREW 4

AJ-A: Fourth aircraft to attack the Möhne Dam. Shot down.

Pilot: Sqn Ldr H.M. Young DFC and Bar

Flight engineer: Sgt D.T. Horsfall

Navigator: Flt Sgt C.W. Roberts

Wireless operator: Sgt L.W. Nichols

Bomb aimer: Flg Off V.S. MacCausland

Front gunner: Sgt G.A. Yeo

Rear gunner: Sgt W. Ibbotson

CREW 5

AJ-J: Fifth aircraft to attack the Möhne Dam. Returned safely.

Pilot: Flt Lt D.J.H. Maltby DFC

Flight engineer: Sgt W. Hatton

Navigator: Sgt V. Nicholson

Wireless operator: Sgt A.J.B. Stone

Bomb aimer: Plt Off J. Fort

Front gunner: Sgt V. Hill

Rear gunner: Sgt H.T. Simmonds

CREW 6

AJ-L: First aircraft to attack the Eder Dam. Returned safely.

Pilot: Flt Lt D.J. Shannon DFC

Flight engineer: Sgt R.J. Henderson

Navigator: Flg Off D.R. Walker DFC

Wireless operator: Flg Off B. Goodale DFC

Bomb aimer: Flt Sgt L.J. Sumpter

Front gunner: Sgt B. Jagger

Rear gunner: Flg Off J. Buckley

CREW 7

AJ-Z: Second aircraft to attack the Eder Dam. Shot down.

Pilot: Sqn Ldr H.E. Maudslay DFC

Flight engineer: Sgt J. Marriott

Navigator: Flg Off R.A. Urquhart DFC

Wireless operator: Wrt Off A.P. Cottam

Bomb aimer: Plt Off M.J.D. Fuller

Front gunner: Flg Off W.J. Tytherleigh DFC

Rear gunner: Sgt N.R. Burrows

CREW 8

AJ-B: Crashed on outward flight.

Pilot: Flt Lt W. Astell DFC

Flight engineer: Sgt J. Kinnear

Navigator: Plt Off F.A. Wile

Wireless operator: Wrt Off A. Garshowitz

Bomb aimer: Flg Off D. Hopkinson

Front gunner: Flt Sgt F.A. Garbas

Rear gunner: Sgt R. Bolitho

CREW 9

AJ-N: Third aircraft to attack the Eder Dam. Returned safely.

Pilot: Plt Off L.G. Knight

Flight engineer: Sgt R.E. Grayston

Navigator: Flg Off H.S. Hobday

Wireless operator: Flt Sgt R.G.T. Kellow

Bomb aimer: Flg Off E.C. Johnson

Front gunner: Sgt F.E. Sutherland

Rear gunner: Sgt H.E. O’Brien

CREW 10

AJ-E: Crashed on outward flight.

Pilot: Flt Lt R.N.G. Barlow DFC

Flight engineer: Plt Off S.L. Whillis

Navigator: Flg Off P.S. Burgess

Wireless operator: Flg Off C.R. Williams DFC

Bomb aimer: Plt Off A. Gillespie DFM

Front gunner: Flg Off H.S. Glinz

Rear gunner: Sgt J.R.G. Liddell

CREW 11

AJ-W: Damaged by flak on outward flight and abandoned mission.

Pilot: Flt Lt J.L. Munro

Flight engineer: Sgt F.E. Appleby

Navigator: Flg Off F.G. Rumbles

Wireless operator: Wrt Off P.E. Pigeon

Bomb aimer: Sgt J.H. Clay

Front gunner: Sgt W. Howarth

Rear gunner: Flt Sgt H.A. Weeks

CREW 12

AJ-K: Shot down on outward flight.

Pilot: Plt Off V.W. Byers

Flight engineer: Sgt A.J. Taylor

Navigator: Flg Off J.H. Warner

Wireless operator: Sgt J. Wilkinson

Bomb aimer: Plt Off A.N. Whitaker

Front gunner: Sgt C.McA. Jarvie

Rear gunner: Flt Sgt J. McDowell

CREW 13

AJ-H: Damaged on outward flight and abandoned mission.

Pilot: Plt Off G. Rice

Flight engineer: Sgt E.C. Smith

Navigator: Flg Off R. Macfarlane

Wireless operator: Wrt Off C.B. Gowrie

Bomb aimer: Wrt Off J.W. Thrasher

Front gunner: Sgt T.W. Maynard

Rear gunner: Sgt S. Burns

CREW 14

AJ-T: First aircraft to attack Sorpe Dam. Returned safely.

Pilot: Flt Lt J.C. McCarthy DFC

Flight engineer: Sgt W.G. Radcliffe

Navigator: Flt Sgt D.A. MacLean

Wireless operator: Flt Sgt L. Eaton

Bomb aimer: Sgt G.L. Johnson

Front gunner: Sgt R. Batson

Rear gunner: Flg Off D. Rodger

CREW 15

AJ-W: Shot down on outward flight.

Pilot: Plt Off W. Ottley DFC

Flight engineer: Sgt R. Marsden

Navigator: Flg Off J.K. Barrett DFC

Wireless operator: Sgt J. Guterman DFM

Bomb aimer: Sgt T.B. Johnston

Front gunner: Sgt H.J. Strange

Rear gunner: Sgt F. Tees

CREW 16

AJ-S: Shot down on outward flight.

Pilot: Plt Off L.J. Burpee DFM

Flight engineer: Sgt G. Pegler

Navigator: Sgt T. Jaye

Wireless operator: Plt Off L.G. Weller

Bomb aimer: Flt Sgt J.L. Arthur

Front gunner: Sgt W.C.A. Long

Rear gunner: Wrt Off J.G. Brady

CREW 17

AJ-F: Second aircraft to attack Sorpe Dam. Returned safely.

Pilot: Flt Sgt K.W. Brown

Flight engineer: Sgt H.B. Feneron

Navigator: Sgt D.P. Heal

Wireless operator: Sgt H.J. Hewstone

Bomb aimer: Sgt S. Oancia

Front gunner: Sgt D. Allatson

Rear gunner: Sgt G.S. McDonald

CREW 18

AJ-O: Only aircraft to attack Ennepe Dam. Returned safely.

Pilot: Flt Sgt W.C. Townsend DFM

Flight engineer: Sgt D.J.D. Powell

Navigator: Plt Off C.L. Howard

Wireless operator: Flt Sgt G.A. Chalmers

Bomb aimer: Sgt C.E. Franklin DFM

Front gunner: Sgt D.E. Webb

Rear gunner: Sgt R. Wilkinson

CREW 19

AJ-Y: Damaged by flak on outward flight. Abandoned mission.

Pilot: Flt Sgt C.T. Anderson

Flight engineer: Sgt R.C. Paterson

Navigator: Sgt J.P. Nugent

Wireless operator: Sgt W.D. Bickle

Bomb aimer: Sgt G.J. Green

Front gunner: Sgt E. Ewan

Rear gunner: Sgt A.W. Buck

Chapter 8: After the Dams Raid

Chapter 9: Afterword

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Index

Chapter 1

Introduction

IN APRIL 2013, about a month before the 70th anniversary of the Dams Raid, the RAF’s most famous Second World War bombing operation, BBC journalist Greig Watson began work on what seemed to be a straightforward enough project. He had an idea for an online feature story: a complete set of pictures of all the aircrew who had taken part in the raid. When the user selected an image, up would pop the name, their nationality, the aircraft they were in and what position they occupied. It seemed a relatively easy task.

However, he soon found that this was not so. Wartime RAF personnel records are not open to the public and, in any case, did not contain photographs. Men moved frequently from unit to unit, and few had any visual archive. And, worst of all, although many big museum collections have hundreds of aircrew photographs, the vast majority have no names attached.

At that stage, I had been writing a regular blog about the Dambusters for about five years. I had started this in 2008, at the same time that my book1 about my uncle, David Maltby, had been published. David had been a pilot on the celebrated raid but had died four months later on another operation. The blog had built up a significant readership and in the spring of 2013, with the 70th anniversary of the raid fast approaching, I decided that I would use it to publish online profiles of all of the 133 men who had taken part in the raid, aiming to complete them all by the end of the year. I planned to illustrate as many posts as possible with a photograph of the subject, although I knew as I started that I didn’t have access to pictures of them all. Maybe the missing pictures would turn up once I began searching for them.

I gave my project the catchy title ‘Dambuster of the Day’ and started publishing the profiles in late March 2013. Then, a couple of weeks later, I got an email from Greig, asking for help with his search. By coincidence, I was working that same day on the first profile for which I could not find a photograph: a 23-year-old Yorkshireman called David Horsfall, who had joined the RAF before the war as an apprentice technician at the age of 16. By May 1943, he had retrained as a flight engineer and had flown on a grand total of two operations, on each cramped into a fold-up seat next to his pilot. His third, and what turned out to be his last, was an attack on the Möhne Dam.

Greig and I spoke on the phone and went through the possibilities. The idea was to publish all the 133 pictures as an interactive ‘picturewall’. He explained what would happen as the user moved their mouse over the individual shots. We discussed whether or not the pictures would appear in random order, which was the BBC’s plan. This made no sense to me, I argued: surely the members of each crew should appear together, and in the order in which they had flown on the raid itself.

Greig had already accepted the fact that some of the faces would have to be cropped from group shots and we went through some sources for these. The Canadian, Australian and New Zealand survivors from the raid had posed the next day for pictures for their own national newspapers, so that was a good starting point. There was also a series of official RAF pictures taken of 617 Squadron in the summer of 1943 and archived in the Imperial War Museum. So it seemed likely that everyone who had got back from the raid had been photographed at some stage during the war.

It quickly emerged that the main problem was going to be finding pictures of the others, the fifty-three men who had died. The popular myth that the Dams Raid aircrew were all battle-hardened veterans who had flown on dozens of previous operations was just that, a myth. It is true that most of the pilots did have considerable operational experience (although four of the nineteen had actually completed fewer than ten operations) but their crews were another matter. It was quite common for an experienced pilot to be given a new crew, and this had been the case for several of those who met their fate on the night of 16/17 May 1943.

The research continued apace. A few low-resolution shots on obscure websites were considered, but discounted because they lacked corroborative evidence. But there were some successes: a portrait of a flight engineer sold at auction ten years ago was found on the auction house’s site. A community news site in West Yorkshire had a photograph of a rear gunner taken at his wedding. A local journalist recalled a bundle of pictures being kept by a bomb aimer’s nephew. We were adding in pictures right up to the day of the anniversary, but when it arrived we were still twelve short.

As soon as the picturewall went live, several more families contacted us so we were able to fill some of the gaps. A few more were uncovered in the following few weeks, including one of flight engineer David Horsfall, taken at RAF Halton training college before the war. But by the middle of July 2013 we were still short of five faces, which was very frustrating. It was then that I looked again at my copy of the memoirs of 617 Squadron’s first adjutant, Flt Lt Harry Humphries, who had died in 2008. This referred to a crewboard that he had kept in in his office, with pictures of all the squadron arranged in rows. If an aircraft went missing, the pictures were removed and kept in what he called a ‘Roll of Honour’ in a ‘rough squadron diary’.2

In the late 1990s, Humphries had decided to sell some of the material which he had collected during the war, and it had been bought by Grantham library. Amongst his collection were three large pieces of card, each mounted with a few small identity card photographs of Dams Raid aircrew. As part of the process of preparing his memoirs for publication Humphries had typed up the captions himself on a manual typewriter.

I had already used the material which was in Grantham. There were seventeen pictures on the three cards – fourteen of aircrew lost in the raid, and three of men who were taken prisoner. They weren’t brilliant quality and had been roughly treated over the years. The individual shots had been cut out with scissors and had obviously already been pasted or stapled onto individual cards at some point in the past, and then removed. They had all the hallmarks of a project which had never been completed. But with only seventeen in the library’s collection, was it possible that the ‘diary’ and the further pictures which Harry had mentioned were still in the possession of the Humphries family?

I got hold of a phone number for Harry’s son, Peter Humphries, and called him. He said immediately that he remembered there being a file containing sheets of paper pasted up with identity card pictures. It was in his loft, with the rest of his father’s papers. ‘Give me the names you are looking for’, he said, ‘and I will check.’ I read out the names: Daniel Allatson, Jack Barrett, Norman Burrows, Jack Marriott, Ronald Marsden. A few hours later, he rang me back: ‘I have them all.’ He read out the names again to check. The following day he emailed me a scan of two pages of yellowing foolscap. Four of the men were on one sheet, the final one was on another.

I rang Greig to tell him the news. ‘I’m looking at the last five pictures. All together on two sheets of paper,’ I said. ‘I hardly believe it. In fact, I actually feel a bit shaky.’ After a period of mutual congratulation, I sent the scans on to him and he said he would discuss with his editors as to when the complete picturewall would go on display.

A few weeks later, the BBC published all the pictures. Their release made the national TV news and was covered in all the papers. The importance of the project was brought home to me when I read what George ‘Johnny’ Johnson, the last British Dambuster, had told Greig: ‘I was looking at faces of colleagues I last saw previously at RAF Scampton at the “All Crews” briefing on the afternoon of 16 May 1943,’ he had said. Greig took the opportunity of asking Johnny to sign two printed copies of the complete wall, one for him and one for me. My copy now hangs in my office.

The list of 617 Squadron crews typed on the morning of the Dams Raid, Sunday 16 May 1943. It was called a ‘Night Flying Programme’ to maintain secrecy until the last possible moment.

The story of the picturewall was just one of the items which showed the continued public interest in the Dambusters story around the time of the 70th anniversary of the raid. A series of events, newspaper stories and TV broadcasts had marked the date, with two of the three living Dambusters, Johnny Johnson and Les Munro – who had flown from New Zealand at the age of 93 – at the forefront of coverage.

So who were the Dambusters, the 133 men who took part in the raid? It is perhaps not surprising that so little is known about some of them, apart from the list of names which appears in the appendices to several books. Those who died during the war are all listed in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission records, but some of these are inaccurate. So the wrong age or place of residence has been copied again and again, unnoticed and unquestioned.

There were nineteen crews, each made up of seven men. Twenty-one crews had been trained up, but two were not available on the day due to sickness. Since it turned out that there were only nineteeen serviceable aircraft this was a happy coincidence. A full crew list of all the men who flew in these nineteen crews was typed up in a ‘Night Flying Programme’ on the morning of the raid. This includes a late substitute in Flt Sgt Ken Brown’s crew, where Sgt Daniel Allatson from one of the crews who had gone sick took the place of Sgt Donald Buntaine, who had also been taken ill, in the front gun turret. Exactly the same names were repeated in the Operations Record Book, written up in the days following the raid.

Of the 133 men:

• 86 were from Britain, 31 were from Canada, thirteen from Australia, two from New Zealand and one from the USA.

• 53 died on the raid, three were captured as PoWs.

• 32 died in action later in the war.

• 48 survived the war.

(The nationality figures include two Canadians and one Australian enlisted in the RAF rather than their indigenous air forces. To add confusion, some of the Canadians were born in the UK but emigrated as a child. The US citizen was Joe McCarthy, who had enlisted in the RCAF.)

Now, for the first time in one book an attempt has been made to do justice to them all, with each man who took part in the raid getting his own entry and photograph in the pages that follow.

In researching this book, I have been lucky in that both the Canadian and Australian national archives have now released the personnel files of the men who died in the war, and I was able to access these. But as of 2018 the RAF’s files are still closed, and although some ‘casualty packs’ from the earliest part of the war have now been released to the National Archives it is not clear when this process will reach the year 1943 nor whether these packs will contain the full details of each man’s service.

But at least we now have a face for each of the 133 men who took part in the Dams Raid. The lives of some are reasonably well documented, but for a few we still know little more than their dates of birth and death, some information about their previous RAF service and, perhaps, some sketchy family details. So this book is just the start of an ongoing research project. Any further information received will be used for a possible second edition and to update the companion website, www.completedambusters.com. Giving each man his credit for taking part in such a piece of history is the least that they deserve.

A note on RAF structures and training

When the Second World War started, the Royal Air Force was only a little over twenty years old. It had grown rapidly since its formation eight months before the end of the previous conflict and by the late 1930s it had established its own distinct service traditions, many of which reflected those in the older branches of His Majesty’s forces. So its officer ranks were given titles such as Flight Lieutenant, Wing Commander and Air Marshal to match those in the Royal Navy and the army, and an officer cadet college at Cranwell mirrored those for the other services at Dartmouth and Sandhurst.

In the period immediately after the 1938 Munich crisis the RAF grew even more swiftly, when the Cabinet gave approval for formation of twelve new fighter squadrons and the gradual re-equipment of the bomber force with heavy bombers. The decision to go for a heavy bomber force was a lucky consequence of the cautious start in rearmament decisions in 1936-7. Earlier rearmament would have left Britain with a fleet of immediately outdated aircraft whereas the arrival of the heavy bomber in 1941-2 eventually made the Allied air forces a much more potent striking force than their Axis equivalent.3

Bomber Command came into existence in 1936, as one of the RAF’s four commands following that year’s reorganisation of the service (the other three being Fighter, Coastal and Training Commands). It was sub-divided into Groups, which by early 1943 were numbered 1–6 and 8. Nos. 1 to 5 Groups were RAF Groups organised by regions, No. 6 Group was under Royal Canadian Air Force command and No. 8 Group was the new Pathfinder force, established in January 1943. Each Group was made up of a number of squadrons.

No. 5 Group had its headquarters in Grantham, Lincolnshire, and its squadrons were spread at various RAF stations over that county and its neighbours. In March 1943, there were ten fully operational squadrons in the group, based at eight different stations.

The prewar expansion of the air force had been done exclusively by recruiting new personnel into the service’s volunteer reserve, and this policy would continue throughout the war. Thus all new recruits started at the rank of Aircraftman and it was only after completing training in their allocated ‘trade’ that some were commissioned as officers.

Tens of thousands of new recruits joined in the first year of the war and this itself gave rise to a whole raft of new problems, with large bottlenecks building up as they moved through the various stages of training.4 Many recruits wanted to become pilots, but not all turned out to be suitable. Some were remustered as other aircrew trades, some were told that they weren’t suitable for the RAF at all. Others indicated when they joined up that they wanted to serve in other capacities.

At the outset of the war, the RAF had just two ‘trades’ available for non-pilot aircrew: observer and a combination wireless operator/airgunner, and there was no automatic promotion to Sergeant for those who achieved these qualiications. Over the next three years, this was changed and then the arrival of the heavy bomber which needed a minimum of seven crew led to the two trades being sub-divided into four: the navigator, air bomber (the official name for what was usually known as a bomb aimer), wireless operator and air gunner,. These changes were ratified by a major conference between the RAF and the air forces of the Dominions and the USA, which was held in Ottawa, Canada, in May and June 1942. As much of the training was conducted abroad, especially in Canada, this was an appropriate venue.

Many of the men who would fly on the Dams Raid had been through training earlier in the war, so had begun their operational careers with a variety of different qualifications. Thus the letter they carried on their single-winged flying badge (such as an O to show that they had qualified as an Observer) might not reflect the position in their aircraft which they later occupied, such as bomb aimer.

The final important position in a 1943 heavy bomber crew of seven to be officially designated was that of its flight engineer. It was recognised that with four engines a second pair of eyes were needed in the cockpit in order to monitor their performance, and at first this position was occupied by a fully qualified second pilot. However, getting a man to this level of skill took the best part of a year. The attrition rate amongst bomber crews meant that a lot of invested time and money was lost if a crew with two pilots was shot down or crashed. And, in reality, the role of a second pilot was often superfluous, with him rarely gaining any actual flying experience. Moreover, both the Avro Lancaster and the Handley Page Halifax had only one set of controls, the Short Stirling being the only heavy bomber with two sets. So in early 1942, it was decided that the second pilot should be replaced by a flight engineer. This new trade had been in existence in some squadrons since late 1940, with training being done at squadron level, but it became formalised in May 1942.

A new training establishment – No. 4 School of Technical Training – was set up at RAF St Athan in Glamorgan and courses were devised to take place there. Initially entrants to this course were recruited from ground crew who had qualified as either fitters or mechanics, although later in 1942, direct entry to the trade were accepted from new recruits. The training was type-specific, as the skills needed to manage the engine performance of a Lancaster, Halifax or Stirling differed considerably. Flight engineers were also given some rudimentary training in flying skills, so that they could take the controls if their pilot was incapacitated. All the flight engineers who took part in the Dams Raid had previously served as ground crew and qualified in their trade between May and November 1942.

As with the other flying trades, each new flight engineer received an automatic promotion to the rank of Sergeant along with his flying badge when he qualified. In all trades – pilots and non-pilots – some men were also commissioned, although in order to achieve this, they were supposed to show they had ‘officer qualities’. Some turned down commissions, not convinced that the small increase in pay and change of status was worth the separation from the colleagues with whom they had gone through training. The Dominion air forces were less hidebound by class distinctions than were the British and it is noticeable that a higher proportion of men received commissions in squadrons and other units which were under their direct command.

During the war, automatic promotion to Sergeant caused a certain amount of resentment amongst some older men, who felt that they might have to wait years to achieve the same rank, but it was felt by the authorities that aircrew did deserve recognition for the fact that they were voluntarily putting their lives at risk.

___________

1 Charles Foster, Breaking the Dams, Pen and Sword 2008.

2 Harry Humphries, Living with Heroes, Erskine Press 2003, p115.

3 Daniel Todman, Britain’s War: Into Battle 1937-1941, Penguin 2017, p99 and p153.

4 Total RAF personnel figures for the first sixteen months of the war are as follows:

3 September 1939

173,958

1 January 1940

214,732

1 January 1941

490,762

Source: www.rafweb.org [Accessed February 2018].

Chapter 2

Planning the raid

WELL BEFORE THE SECOND WORLD WAR STARTED the British Air Ministry had set up an Air Targets Sub-Committee to look for possible targets in Germany in the event of war. The power stations and coking plants in Germany’s heavily industrialised Ruhr Valley were amongst the important strategic objectives which were identified. It was then argued that neutralisation of these could be achieved by the destruction of just two dams, those at the Möhne and Sorpe. If other dams, such as the Eder, were also destroyed, severe damage to the canal system and drinking water could be added to the effect on hydro-electric power and steelmaking.

The planners however recognised that bombs of sufficient explosive power did not yet exist, and even if one could be developed there was no agreement as to how it should be delivered. Several papers were circulated and suggestions included torpedos and low level bombing of the air side of the dam wall. When war came, an attack on the dams remained on the agenda. Significantly, in July 1940 Air Marshal Sir Charles Portal, at that stage the AOC-in-C of RAF Bomber Command, wrote to the Secretary of State for Air arguing ‘that the time has arrived when we should make arrangements for the destruction of the Möhne Dam’.5 Later that year Portal became Chief of the Air Staff – the head of the Royal Air Force – and it was in this position he was later able to give support for the Dams Raid at a number of crucial points.

It was recognised that in order for a successful attack to be mounted three separate developments needed to occur. There needed to be a bomb or other explosive device of sufficient size, an aircraft big enough to carry it and aircrew who could be trained in any special delivery method.

From the very beginning of the war the assistant chief designer of the aircraft manufacturer Vickers-Armstrongs, Barnes Wallis, had taken an interest in methods for attacking German dams. He and his small staff had been evacuated from the main Vickers works at Weybridge and were given offices in the clubhouse of the nearby Burhill Golf Club. During 1940 Wallis started his own research, combing through contemporary German articles about the construction of the Möhne Dam in 1913. He was convinced that the standard 1,000lb small bombs would never be effective and devised a much larger 22,400lb bomb with a ‘R100’ or peardrop shape. (In the late 1920s, Wallis had headed the design team which had built the R100 airship.) Amongst the small group of scientists to see Wallis’s early research was Benjamin Lockspeiser, the Deputy Director of Scientific Research at the Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP), who would later solve the problem of how to calculate and maintain the altitude of a low-flying bomber. Lockspeiser disagreed with the idea of a peardrop shape for such a large bomb, arguing that it should have a sharply pointed nose. However, with no aircraft available which could carry such a huge payload, Wallis turned his attention to finding a different method.

By coincidence, a team of engineers from the Building Research Station in Garston, near Watford, who had been working on the effects of explosives on structures since before the war, were transferred to the Road Research Laboratory in Harmondsworth. Led by A.R. Collins, they had also identified the Möhne Dam as a possible target.

Wallis met Collins, along with Dr W.H. Glanville and Dr A.H. Davis, the director and assistant director of the laboratory, and they discussed how much damage would be caused if a large explosion occurred on the upstream side of the Möhne Dam, very close to the wall. On an unknown date in late 1940, Glanville and Wallis held a meeting with Dr Norman Davey of the BRS,6 and they decided that the most effective way to determine the weight of explosive needed, and the optimum location to detonate it to breach the dam, was to construct a scale model and then blow it up. Davey agreed to build this at Garston, and so work began in November 1940 in a secluded corner of the site. Some 2 million miniature concrete blocks were made, and the construction took about six weeks. The model was completed on 21 January 1941, and the first explosive test took place the following day. In all, ten explosions were carried out and the model – which can still be seen at Garston – was badly damaged.7

Later, at Harmondsworth, Collins made further 1/50-scale models of both the Möhne Dam and a similar one in Italy, and in late 1940 and early 1941 wrote a series of reports for MAP on his results.

Wallis took all this information, and in March 1941 wrote a massive 117-page paper. He circulated more than 100 copies (including sending one to an Evening Standard journalist). He sent several to his friend Gp Capt Frederick Winterbotham, the RAF officer who was the Chief of Air Intelligence at MI6. He had become a useful ally with a wide range of contacts and Winterbotham used these to make sure that Sir Henry Tizard, MAP’s scientific adviser, and other influential people received copies.

The full title of Wallis’s paper, ‘A Note on a Method of Attacking the Axis Powers’, doesn’t do justice to the wide range of subjects covered. With five appendices, eight tables, thirty-two diagrams and a quotation from Thomas Hardy, it described the current bombing campaigns as ‘puny efforts’ and proposed a different strategy, involving much bigger 4,000 and 10,000lb bombs, and a much larger aircraft in order to deliver them.

The note was eventually considered by various Whitehall committees and sub-committees. Unfortunately for Wallis, the final answer to his proposals was ‘No’. As Wallis knew, at that point four-engine heavy bombers were only just becoming available, and there was no enthusiasm for diverting resources into developing an even bigger one. It was also felt that the explosive in a larger peardrop-shaped bomb would not all explode at the same time, thereby reducing its impact.

But at least Wallis’s ideas had been considered, and he had got an audience interested in his ideas. Although disheartened, Wallis went back to his research and gave the matter further thought. Then came his brainwave. ‘Early in 1942,’ he later wrote, ‘I had the idea of a missile, which if dropped on the water at a considerable distance upstream of the dam would reach the dam in a series of ricochets, and after impact against the crest of the dam would sink in close contact with the upstream face of the masonry.’8

Then began Wallis’s famous experiments in his garden in Effingham using his children’s marbles, firing them from a catapult across the surface of a tub of water, where they bounced. They landed second bounce on a table, where the fall was marked in chalk by one of his children. He also modified the shape of his bomb, believing that if it was a spherical shape and detonated in the centre the explosion would reach all points on the surface at the same time.

At this stage, thinking that the weapon would be most useful for the Fleet Air Arm, he wrote another paper and sent it to another of his circle of friends, Professor P.M.S. Blackett, the scientific adviser to the Admiralty. Blackett could also see its relevance for the RAF, and informed Sir Henry Tizard at MAP. Tizard had been consulted before about Wallis’s earlier paper, but this time he saw merit in the idea and travelled to Burhill Golf Club to meet Wallis again. Wallis found him ‘kindly and very knowledgeable’ and through him secured permission to use the large water tanks at the National Physical Laboratories in Teddington for further research.

Work began at Teddington on 9 June 1942 and continued until September. At some point, Wallis decided to introduce back spin to the projectile, probably following discussions with Vickers employee and keen cricketer George Edwards. A succession of research grandees – including Tizard, Air Vice Marshal F.J. Linnell (from MAP) and Rear Admiral E.de F. Renouf (the navy’s Director of Special Weapons) – came to see the tests in action, and Linnell gave permission for a Wellington to be used for test drops.

Meanwhile Collins and his colleagues at the Road Research Laboratory had been given permission to scale up their dam experiments on the disused Nant-y-Gro dam in the Elan Valley in Powys. Wallis travelled to the site to watch the first test using an upstream explosion on 1 May, but this was unsuccessful. However, after further examination of the Harmondsworth models, it was decided to place an explosive charge in contact with the base of the dam. On 24 July a mine with 279lb of explosive was placed in at the centre of the dam, 7ft 6in below its crest, and detonated. The result was so spectacular – a huge waterspout and the centre of the dam punched out – that Collins, who was recording events on a ciné camera, temporarily stopped filming. Extrapolation of the results showed that a similar result could be achieved on a larger dam with a 7,500lb bomb. Crucially, a single bomb of this weight could be carried by the new four-engine Avro Lancaster, which had been in service with the RAF since January that year.

The development of four-engine heavy bombers can be argued as being one of the most crucial prewar decisions taken by the UK government, contrasting with Germany’s perseverance with the medium two-engine bomber throughout the war. And the delay in starting rearmament, caused by the vacillation of the Baldwin government before 1936, in fact proved to be a benefit since commissioning of new aircraft at this time would have left the RAF beginning the war with a fleet of immediately outdated aircraft.9

The first heavy bomber to go into production was the result of a contract awarded to Short Brothers to build the Stirling aircraft. Another government specification led to contracts for the firms of A.V. Roe (commonly known as Avro) and Handley Page. Avro first developed the Manchester bomber, which used two large Rolls Royce Vulture engines, but this proved unsatisfactory and it was superseded by the four-engine Lancaster, using the smaller but more efficient Rolls Royce Merlin engine. Handley Page’s Halifax was also designed with four Merlin engines.

Of these three, the Lancaster quickly became the most potent striking force. Production of the Halifax also continued throughout the war, with more than 6,000 manufactured, but the Stirling, of which some 2,000 were built, fell out of favour. The Lancaster had a massive uninterrupted bomb bay (something which would prove important later in the war when the Barnes Wallis-designed Tallboy and Grand Slam bombs became available) and large fuel tanks, and these put targets in both the east of Germany and Italy in range. By the end of 1942 most of the squadrons in Bomber Command’s 5 Group had been equipped with Lancasters, and it would be from this group that the aircrew who would make up the Dams Raid strike force would eventually be selected.

Meanwhile Wallis was busy building a prototype spinning device, and its first airborne trial of a spinning device took place on 4 December. A modified Wellington flown by Joseph (‘Mutt’) Summers, the Vickers-Armstrongs chief test pilot, with Wallis himself as bomb aimer took off from Warmwell airfield and flew towards the test range at Chesil Beach, on the Dorset coast. Flying parallel to the coastline, Wallis dropped the spherical dummy but it shattered on impact with the water. Further trials took place the following week and into the New Year and it wasn’t until the fourth trial on 23 January, when a wooden sphere was used for the first time, that a successful series of bounces occurred. Thirteen were recorded, after the dummy rotating at 485rpm had been dropped from a height of 42ft with the Wellington travelling at 283mph.

Several more were dropped successfully over the following days. Then Wallis set about trying to get agreement to develop two separate versions of the weapon: a large version, called Upkeep, for use in a Lancaster against the dams, and a smaller version, Highball, which could be dropped by a Mosquito against shipping. He began the process of hawking film footage from Chesil Beach and Teddington around Whitehall. To go with this, he had written another paper, ‘Air Attack on Dams’. As it also included material on maritime targets it was first sent to Rear Admiral Renouf, and then to various Air Ministry contacts. He also sent it to Lord Cherwell, Churchill’s scientific advisor at the Cabinet Office. This was accompanied by a covering letter which claimed that Mosquitoes would be ready to test the Highball weapon in six to eight weeks but ‘unfortunately have overshadowed the question of the major German dams.’ Wallis went on: ‘if a high-level decision’ were taken to give equal priority to both weapons ‘we could develop the large sphere to be dropped from a Lancaster bomber within a period of two months.’

The one senior RAF officer who was not convinced was the man who commanded the aircrew who would be needed to drop the weapon, Air Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, now the AOC-in-C of Bomber Command. His Senior Air Staff Officer, Air Vice Marshal Robert Saundby sent him a lengthy minute on 14 February, outlining the research and testing of Highball and considering the possibility of a ‘similar weapon’ for the special purpose of destroying dams, in particular the Möhne. A specially modified Lancaster would be needed and the attack would be need to be made when the dam was full or nearly full. One squadron would have to be nominated, depriving Bomber Command of its strength for ‘two or three weeks’ for training. The tactics are not difficult, Saundby concluded, somewhat optimistically.

Harris was not at all convinced. He handwrote a scathing note on Saundby’s minute:

This is tripe of the wildest description. … there is not the smallest chance of it working. To begin with the bomb would have to be perfectly balanced around it’s [sic] axis otherwise vibration at 500RPM would wreck the aircraft or tear the bomb loose. I don’t believe a word of it’s [sic] supposed ballistics on the surface. … At all costs stop them putting aside Lancs & reducing our bombing effort on this wild goose chase. … The war will be over before it works – & it never will.10

Harris had been in charge of Bomber Command for just over a year, and was busy implementing his strategy of area bombing. Ultimately, he was most concerned that a squadron of his most effective bombers was not going to be available for this task. Although the production of Lancasters was now running at full tilt, only about 120 new ones emerged from the factories every month.

However, Harris was now in a minority in the senior ranks of the RAF. A few days later, on 19 February at Vickers House in London, Wallis got to show his films to the two of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the heads of both the navy and the air force, Admiral Sir Dudley Pound and Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal.

Harris was still not appeased. Nor was he impressed with the films when Wallis went to visit him at Bomber Command HQ in High Wycombe on 22 February. He sent Portal another of his impassioned letters.

All sorts of enthusiasts and panacea-mongers are now careering round MAP suggesting the taking of about 30 Lancasters off the line to rig them up for this weapon, when the weapon itself exists so far only within the imaginations of those who conceived it. … I am prepared to bet that the Highball is just about the maddest proposition as a weapon that we have yet come across – and that is saying something. … Lancasters make the greatest contribution to our bomber offensive, which we have to carry on so continuously against such great odds. The heaviest of these odds arises from the continual attempts to ruin Lancasters for some specialist purpose or to take them away for others to use.11

Portal tried to smoothe Harris’s feathers. He accepted that the weapon might come to nothing, but it was worth conducting a trial in a Lancaster to see if it could work. ‘I can assure you that I will not allow more than three of your precious Lancasters to be diverted for this purpose until the full scale experiments have shown that the bomb will do what is claimed for it,’ he wrote. ‘I shall ask for the necessary conversion sets to be manufactured but there will be no further interruption of supply of Lancasters to you until it is known that the difficulties to which you refer have actually been overcome.’12 Harris reluctantly accepted the decision.

However, on 23 February there was nearly a fatal setback. Wallis and the Weybridge works manager Hew Kilner were called to a meeting in London by Vickers chairman Sir Charles Craven. Craven said that Wallis was making a nuisance of himself at MAP and by involving Vickers-Armstrongs directly or indirectly, he was damaging the company’s interests and moreover had offended the Air Staff. Air Vice Marshal Linnell of MAP had apparently told Craven that Wallis should ‘stop this silly nonsense about the destruction of the dams’. Wallis was shocked and immediately offered his resignation, whereupon Craven reacted vigorously and accused him of ‘mutiny’.13

However, Linnell seems to have acted unilaterally, and was not aware that Portal had approved the allocation of three Lancasters. Two days later, the storm blew over and Wallis was asked to attend a meeting at MAP the following day, which would be chaired by Linnell himself.

The meeting got underway at 1500, in Linnell’s office at the Ministry in Millbank. Wallis and Craven were there from Vickers-Armstrongs, and Avro was represented by Roy Chadwick, the designer of the Lancaster. Also present were Air Vice Marshal Ralph Sorley, Air Cdre John Baker and Gp Capt Wilfred Wynter-Morgan (Air Ministry) and Norbert Rowe from MAP.

Linnell had been thoroughly briefed by Portal, and so there were no recriminations or repetition of doubts about the project. Instead, the meeting proceeded to set in motion what would soon become known as Operation Chastise. Linnell announced that Portal wanted ‘every endeavour’ to prepare aircraft and weapons for use in the late spring of 1943, and for both Avro and Vickers-Armstrongs to give the work the highest priority. Three Lancasters were to be prepared for trials as soon as possible, with another twenty-seven to be similarly modified. Baker, the Director of Bombing Operations, said that the best possible date for an attack on the dams would be 26 May, so all aircraft and mines should be delivered by 1 May to allow for training and experiments. Wallis pointed out that ‘no detailed scheme’ for preparing the modified Lancasters had yet been agreed, so following discussion the line of demarcation between Avro and Vickers-Armstrongs was settled, with the latter handling the attachment arms and driving mechanism and the mine itself. Avro agreed to send draughtsmen to Weybridge immediately to work on this. Wallis revealed that no detailed drawings for Upkeep yet existed, but that he hoped to be able to send them to the works manager in Newcastle ‘in ten days to a fortnight’. Wynter-Morgan said that Torpex explosive was available but that it would take three weeks to fill 100 mines and that it wouldn’t be possible to design the self-destructive mechanism until the detailed drawings were ready.

Everything was very tight, and Wallis’s often-repeated assertion that the whole process could be done in eight weeks would be tested to the limit. That was almost exactly the timescale now proposed. He recalled later that as he left, he felt ‘physically sick’ because his bluff had been called and that he realised the terrible responsibility of making good all my claims’.

Norbert Rowe, a religious man, offered to send him the prayer to St Joseph which he himself used at times of stress. Wallis was going to need all the help he could get.

___________

5 John Sweetman, The Dambusters Raid, Cassell 2002, p26. This chapter owes much to Sweetman’s first three chapters.

6 Dr Norman Davey, Some reflections on the Möhne Dam, unpublished paper, Building Research Establishment, 1993. See www.bre.co.uk/dambusters [accessed January 2018].

7www.bre.co.uk/dambusters.

8 Sweetman, Dambusters Raid, p54. This section draws heavily on the following pages of Sweetman’s book.

9 Daniel Todman, Britain’s War, Penguin 2017, p99.

10 National Archives, AIR 14/595.

11 Harris Papers, H82. RAF Museum, cited in Leo McKinstry, Lancaster: the Second World War’s greatest bomber, John Murray 2009, p266.

12Ibid.

13 Sweetman, Dambusters Raid, p78.

Chapter 3

Selecting the aircrew

THE CLOSE OF THE MEETING IN MILLBANK on Friday 26 February 1943 left Barnes Wallis with much work to do on finishing the design of the proposed weapon and Avro agreeing to start production of three modified Lancasters. Thus, two of the three conditions needed for an attack on the dams were in the process of being fulfilled. The third item, the selection and training of suitable aircrew, began just over two weeks later on Monday 15 March 1943 when the AOC-in-C of Bomber Command, Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris chose the command’s 5 Group to undertake the work. He told the group’s Air Officer Commanding, Air Vice Marshal the Hon Ralph Cochrane, that he would need to set up a new squadron to undertake the operation, but emphasised that he should not reduce the efforts of his main force.

Three days later, on Thursday 18 March, Wg Cdr Guy Gibson, who had just finished a tour of operations as CO of 106 Squadron, was summoned to a meeting with Cochrane at Group HQ in Grantham. The day before, Harris’s Senior Air Staff Officer, Air Vice Marshal Robert Oxland, had written two important memos. The first was to the Director of Bomber Operations, Air Cdre Sydney Bufton, stating that the Commander in Chief [Harris] had decided ‘this afternoon’ that a new squadron should be formed.

The second memo was sent to Cochrane. It described the new Upkeep weapon: it was, Oxland said, a spherical bomb which if spun and dropped from a height of 100ft at about 200mph would travel 1,200 yards.

It is proposed to use this weapon in the first instance against a large dam in Germany, which, if breached, will have serious consequences in the neighbouring industrial area… The operation against this dam will not, it is thought, prove particularly dangerous [sic], but it will undoubtedly require skilled crews. Volunteer crews will, therefore, have to be carefully selected from the squadrons in your Group.14

It is worth noting that Oxland called the weapon a spherical bomb, but it was soon changed to a large cylinder, much the shape and size of the heavy roller used on a cricket field. At first, the cylinder was enclosed in a wooden sphere, but this proved impractical so was not used.

This second memo led to a circular being sent by 5 Group to all its squadrons, asking them to provide a pilot and crew for a new squadron, for a special one-off operation. No copies of the circular survive, but it would seem to have specified that the crew should be experienced, even perhaps have completed a full tour. Individual squadron commanders interpreted this circular in different ways, and most were probably reluctant to lose one of their best crews. Some however entered into the spirit and nominated an experienced captain. Others chose to offload someone with fewer operations, but perhaps the right ‘press-on’ attitude. In some squadrons – notably 97 Squadron – volunteers were called for. In others, people were told they were moving, perhaps in the time-honoured service tradition of being told that they were volunteering.

At that stage there were ten fully operational squadrons in 5 Group. Nos 44, 49, 50, 57, 61, 97, 106, 207 and 467 Squadrons eventually provided aircrew, some indirectly. No 9 Squadron was the only squadron in the group not to send a crew, although a supernumerary air gunner on its strength, Sgt Victor Hill, was posted to 617 Squadron as a late replacement on 7 May 1943.

The method by which the crews were actually selected is incontrovertible, and directly contradicts the account given by Gibson himself in his book Enemy Coast Ahead, written in mid 1944. Here he states that he personally chose not only the pilots but also their crews, giving the names to a staff officer he called Cartwright. He adds that the process took him just an hour:

It took me an hour to pick my pilots. I wrote all the names down on a piece of paper and handed them over to him. I had picked them all myself because from my own personal knowledge I believed them to be the best bomber pilots available. I knew that each one of them had already done his full tour of duty and should really now be having a well-earned rest; and I knew also that there was nothing any of them would want less that this rest when they heard that there was an exciting operation on hand. Cartwright helped a lot with the crews because I didn’t know these so well, but we chose carefully and we chose well.15

He goes on to elaborate his story with a description of finding all his men waiting for him in the officers’ mess at Scampton, on the day he arrived. This is then followed by an impromptu party. Paul Brickhill must have relied on Gibson’s book as his source, since he has a similar account in The Dam Busters. Even though he wrote this six years after the war and therefore had the opportunity to interview many of the aircrew involved, he evidently didn’t bother to check what had actually occurred:

A staff officer helped [Gibson] pick aircrew from the group lists. Gibson knew most of the pilots – he got the staff man to promise him Martin and help him pick the navigators, engineers, bomb aimers, wireless operators and gunners; when they had finished they had 147 names – twenty-one complete crews, seven to a crew. Gibson had his own crew; they were just finishing their tour too, but they all wanted to come with him.16

The 1955 film of the same name follows the same scenario, with both giving a supporting role to Gibson’s famous beer-drinking pet dog.

This whole narrative is nonsense, but unfortunately the story that Gibson ‘personally selected’ every ‘Dambuster’ persists, even today. The truth is that the process was much more drawn out, and the crews arrived over a period of more than two weeks. The only pilots destined for the new squadron who could have been at Scampton on the day Gibson arrived were those in 57 Squadron, which was also based there. But at this stage, they were unaware of their imminent transfer so it is unlikely that Gibson spent the first evening knocking back pints with them.

We know that Gibson certainly asked for some pilots by name, because he spoke to Mick Martin, Joe McCarthy and David Shannon by telephone. This was confirmed by all three after the war. He may have also directly contacted a few others. One of these was probably John Hopgood who, like Shannon, had served under him at 106 Squadron. Gibson had never met many of the other pilots including Melvin Young and Henry Maudslay, who would be his new flight commanders.

So why did Gibson choose to over-elaborate the story when writing his own account? The answer, as Richard Morris discovered when writing his biography of Gibson,17 is that he probably didn’t write the account at all. The myth had already been created in a pair of press articles published in December 1943, credited to Gibson but both likely to have been written by ‘ghostwriters’. The first was in the American magazine Atlantic Monthly in December 1943. The second was in the London newspaper, the Sunday Express, on 5 December 1943.

Articles published under Guy Gibson’s name in (left) Atlantic Monthly, December 1943, and (right) the Sunday Express, 5 December 1943.

For example, he wrote in Atlantic Monthly:

It took me an hour to pick my squadron. I wrote the names down on a piece of paper and gave them to a man with a red mustache who was sitting behind a huge desk. …

I knew them all. I had picked them myself because I honestly believed from my own personal knowledge that they were the best bomber crews in the RAF. I knew that each one of them had already done his full tour of duty and should now be having a well-earned rest; and I knew also that there was nothing that any of them would want less than this rest when they heard that there was an exciting operation on hand.18

A very similar passage appears in the Sunday Express article, as can be seen in the illustration above.

The probable reason for the first article’s publication in an American magazine is because it coincided with a four-month tour by Gibson of Canada and the USA. As to who actually wrote it, there is the strong possibility that it was the writer Roald Dahl, then serving as the Assistant Air Attaché at the British Embassy in Washington DC, with the rank of Flight Lieutenant. He was one of the wide range of service people and civic leaders who encountered Gibson on his travels. Earlier in the war, Dahl had been a fighter pilot in both North Africa and Greece, but had been forced to give up flying after an accident. He had arrived in Washington in April 1942, and was mainly involved in intelligence work. By the time Gibson met him sixteen months later he had made contacts with the movie scene in Hollywood and had also developed a career as a writer, with several short stories published and film treatments drafted. Feted as a great new talent, he had also become heavily involved in the Washington social scene.

A few months before meeting Gibson, on 31 May 1943, Dahl had sent a proposition to the Air Ministry in London for a film on the effects of bombing. This didn’t specifically involve the Dams Raid, but given that this had taken place only two weeks previously it was doubtless in his mind. He had already been introduced to the American film director Howard Hawks, and he must have also contacted him at this time because, at the end of July 1943, Dahl’s colleague in the Air Attaché’s office, Sqn Ldr G. Allen Morris, wrote to Air Chief Marshal Harris, the AOC Bomber Command, asking for ‘every possible releasable detail’ about the Dams Raid. Hawks, he said, had asked Dahl to write a script about it.

By early September, Gibson was in New York, and Dahl travelled to the city to meet him. Dahl wrote in a letter to his mother that Gibson had flown from Canada ‘to see me about the “Bombing of the Dams” script which I am trying to do for Hollywood in my spare time. I’ve got all the material now and all the photos I want. I’ve got everything, in fact, except the time in which to do it.’19 By 21 September, he had completed the script, calling it ‘The Dam’, and sent it to London for vetting.