39,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

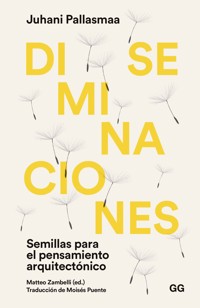

A collection of the writing of the highly influential architect, Juhani Pallasmaa, presented in short, easily accessible, and condensed ideas ideal for students

Juhani Pallasmaa is one of Finland’s most distinguished architects and architectural thinkers, publishing around 60 books and several hundred essays and shorter pieces over his career. His influential works have inspired undergraduate and postgraduate students of architecture and related disciplines for decades. In this compilation of excerpts of his writing, readers can discover his key concepts and thoughts in one easily accessible, comprehensive volume.

Inseminations: Seeds for Architectural Thought is a delightful collection of thoughtful ideas and compositions that float between academic essay and philosophical reflection. Wide in scope, it offers entries covering: atmospheres; biophilic beauty; embodied understanding; imperfection; light and shadow; newness and nowness; nostalgia; phenomenology of architecture; sensory thought; silence; time and eternity; uncertainty, and much more.

- Makes the wider work of Pallasmaa accessible to students across the globe, introducing them to his key concepts and thoughts

- Exposes students to a broad range of issues on which Pallasmaa has a view

- Features an alphabetized structure that makes serendipitous discovery or linking of concepts more likely

- Presents material in short, condensed manner that can be easily digested by students

Inseminations: Seeds for Architectural Thought will appeal to undergraduate students in architecture, design, urban studies, and related disciplines worldwide.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 620

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Preface

A

An Artwork is…

Aestheticization

Amplifiers of Emotions

Animal Architecture

Anonymity

Architectural Courtesy

Architecture and Being

Architecture and Biology

Architecture as Experience

Architecture as Impure Discipline

Architecture is Constructed Mental Space

Art as Representation and Reality

Architecture, Reality and Self

Art vs Science I

Art vs Science II

Artists as Phenomenologists and Neurologists

Artists vs Architects

Atmospheres in Architecture

Atmospheric Intelligence

Atmospheres in the Arts

Atmospheric Sense [The]

B

Beauty

Beauty and Ethics

Beauty and Time

Being in the World

Biophilic beauty

Books (and architecture)

Burial architecture

C

Cinema and Architecture

Cinema and Painting

Collaboration

Collective Memories

Complexity of Simplicity [The]

Computer and Imagination

Computerised Hand [The]

Condensing

Craftsmanship

Creative Imagination

Creative Team Work?

D

Depthlessness

Design Process

Digital Universe

Drawing

Drawing by Hand

E

Education

Elementarism

Embodied Existence

Embodied Knowledge and Thought

Embodied Memory

Embodied Understanding

Emotional Echo

Emotions

Emotions and Creative Thought

Empathy

Encountering Architecture

Evocativeness

Exchange

Existential Space I

Existential Space II

Experience has a Multi‐Sensory Essence

Eyes

F

Fragile Architecture

Forgetting

Fragments

Fusion of the Self and the World

G

Generosity

H

Hapticity

Hearth

Homelessness

Horizons of Meaning

Humility

I

Ideal Client

Ideals

Identity

The Existential Task of Architecture (2009)

Imaginary

Imperfection

L

Language of Matter [The]

Liberating Images vs Withering Images

Light

Limits

Limits and Immensity

Lived Space

M

Man

Matter and Time

Meaning

Memory

Metaphor

Microcosms

Modes of Thinking

Moving

Museums of Time

Myth

N

Newness

Nihilism

Nomadism and Mobility

Nostalgia

Nowness and Eternity

O

Odours in Architecture

Optimism

P

Painter, Architect and Surgeon

Painting and Architecture

Perfection and Error

Peripheral Vision

Personality Cult

Phenomenology of Architecture

Philosophy in the Flesh

Physical and Mental Landscape

Playing with Forms

Present Tense of Art

R

Rationalising Architecture

Realism and Idealization

Reality and Imagination

Reality vs Symbol

Reconciling

Relational Experiences

Reverse Interpretation

Roots and Biology

Ruins

S

Sacredness

Senses I

Senses II. How many senses do we have?

Silence, Time and Solitude

Smells

Sound

Space and Imagination

Space‐Time

Spatialized Memories

Speed

Speed and Time

Stairways of Cinema

Sublime

Sustainability

Symbol

Synaesthesia

Syncretic Imagination

T

Tactility and Materiality of Light

Tasks of Architecture [The]

Tasks of Art [The]

Theorizing Architecture

Thinking Hand [The]

Time

Time and Eternity

Touch

Tradition

Triad

U

Uncertainty

Unfocused Vision

V

Verbs vs Nouns

W

Water and Time

Inseminations: Seeds for Architectural Thought

Preamble

The Psychological Digging

The Approach: Jumps Vs Linear Thought

Pallasmaa's Reply to Our Proposal

A Weak Structure: The Alphabetical Order

Literary References

What is the Book and How Should We “Use” It?

Final Thoughts

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

xxi

xxii

xxiii

xxiv

xxv

xxvi

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

131

132

133

134

135

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

177

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

261

262

263

264

265

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

Inseminations

Seeds for Architectural Thought

Juhani Pallasmaa and Matteo Zambelli

Copyright

This edition first published 2020

© 2020 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by law. Advice on how to obtain permission to reuse material from this title is available at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

The right of Juhani Pallasmaa and Matteo Zambelli to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with law.

Registered Offices

John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Office

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, customer services, and more information about Wiley products visit us at www.wiley.com.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats and by print‐on‐demand. Some content that appears in standard print versions of this book may not be available in other formats.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty

In view of ongoing research, equipment modifications, changes in governmental regulations, and the constant flow of information relating to the use of experimental reagents, equipment, and devices, the reader is urged to review and evaluate the information provided in the package insert or instructions for each chemical, piece of equipment, reagent, or device for, among other things, any changes in the instructions or indication of usage and for added warnings and precautions. While the publisher and authors have used their best efforts in preparing this work, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives, written sales materials or promotional statements for this work. The fact that an organization, website, or product is referred to in this work as a citation and/or potential source of further information does not mean that the publisher and authors endorse the information or services the organization, website, or product may provide or recommendations it may make. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a specialist where appropriate. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

Library of Congress Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data

Names: Pallasmaa, Juhani, 1936‐ author. | Zambelli, Matteo, 1968‐ author.

Title: Inseminations: seeds for architectural thought / Juhani Pallasmaa,

architect, Helsinki; Matteo Zambelli, architect, Florence.

Description: Hoboken, NJ : Wiley, 2020. | Includes bibliographical

references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019046580 (print) | LCCN 2019046581 (ebook) | ISBN

9781119622185 (hardback) | ISBN 9781119622208 (adobe pdf) | ISBN

9781119622239 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Architecture–Philosophy.

Classification: LCC NA2500 .P353 2020 (print) | LCC NA2500 (ebook) | DDC

720.1–dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019046580

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019046581

Cover Design: Wiley

Cover Image: © Vadym Kur/123RF

Cover suggested by Susanna Cerri, DIDA Lab, Florence, Italy

Preface

I never intended or deliberately decided to become an architectural writer, critic or theorist. I have unnoticeably drifted from my architectural practice into thinking and writing about this art form, and for almost one decade since I closed the design activities of my office, I have found myself writing practically full time.

I wrote my first article in 1966 and during the past years I have written an essay, lecture, or preface to a book by someone else roughly every second week. I have now published over 60 books and over 400 essays. I confess that I have gradually developed a way of writing that is similar to my way of designing. I write spontaneously without an outline or clear plan, in the same way that I used to sketch my architectural projects. I feel that I have not really changed my craft, as I continue to do the same thing, to imagine architectural situations, encounters and experiences, now in words instead of form and matter.

In the late 1970s, I read Gaston Bachelard's Poetics of Space1 (the book was pointed out to me by Daniel Libeskind in the book shop of the Cranbrook Academy), and it opened up a new world to me, the realm of poetic imagination and imagery, a world where perception, thought, imagination and dreams are united. I realized that the world is not out there objectively, as it is fundamentally of our own perceptual and mental making. I became aware of the existential and poetic ground of architecture as opposed to visual aesthetics, compositions or utilitarian issues. I began to read philosophers, psychologists of creativity, scientists, mainly physicists and natural scientist and later also neuroscientists. I have also eagerly read novels and poetry. Books open up marvellous worlds, those of imagination, the most significant worlds for me.

In 1985, I wrote an essay entitled ‘The Geometry of Feeling’,2 which has later been republished as an example of architectural phenomenology in some anthologies on architectural writing and theory. I must say honestly, that only while working on that essay I became aware of phenomenology as a line of philosophical enquiry, and I added a short chapter on this philosophical approach in this essay, mainly for the purposes of clarifying my own view. Yet, even today, I do not claim to be a phenomenologist, due to my lack of formal philosophical education. I would rather say that my current views of architecture and art are parallel to what I understand the phenomenological stance to be. My ‘phenomenology’ arises from my half a century of experiences as an architect, teacher, writer and collaborator with numerous artists, as well as my excessive travels around the world and my experiences of life in general.

The Dutch phenomenologist JH van den Berg argues surprisingly: ‘Painters and poets are born pheneomenlogists’.3 The neurobiologist Semir Zeki, who studies the neurological ground of art and aesthetics, makes a parallel argument: ‘Most painters are also neurologists’, in the sense of intuitively understanding the neurological principles of brain activities.4 These statements speak for the power of the artist's intuition. I believe that I am similarly a ‘born phenomenologist’ through my formative childhood experiences and observations at my farmer grandfather's humble farm house in Central Finland during the war years of 1939–1945. My thinking is essentially ‘a farm boy’s phenomenology' refined by my later engagement in the artistic world. Yet, in recent years, I have had the opportunity of lecturing with some of the leading phenomenologists in several countries.

I understand phenomenology in accordance with the notion of the founder of the movement, Edmund Husserl, as ‘pure looking’, an innocent and unbiased encounter with phenomena, in the same manner that a painter looks at a landscape, a poet seeks a poetic expression for a particular human experience, and an architect imagines an existentially meaningful space. I have also understood that the original meaning of the Greek word theorein was to observe, not to speculate. My theorizing is an intense look at things in order to see their essences, connections, interactions and meanings. I also feel sympathy for Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's view of science, which he called ‘zarte empirie’, delicate empiricism,5 a thinking that aspires to observe without changing and violating the phenomenon in question. I write in the associative manner of literary essays, and I have no hesitation in combining scientific findings with experiential and sensory observations or phenomenological formulations. I also try to achieve literary qualities in my writings after I have realized that aesthetic qualities of language make the reader more receptive; she receives simultaneously the intellectual meaning and an aesthetic and emotive impact.

In The Book of the Disquiet, the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa – who wrote in 52 pseudonyms – confesses: ‘I was a poet animated by philosophy, not a philosopher with poetic faculties’.6 As I have no academic training in philosophy, I wish to paraphrase the poet's confession: I am an architect animated by philosophy, not a philosopher with architectural interests. I must confess that I am an amateur thinker although I have read numerous books by philosophers due to my interest in the enigma of human existence, consciousness and the essence of knowledge. I consider myself a craftsman and amateur, and I have even developed a suspicion for expertise in the manner of the statement of Joseph Brodsky, the poet: ‘A craftsman does not collect expertise, he collects uncertainties’.7 Through my long experience as architect and designer, I have become ever more uncertain, as widening knowledge complicates reality instead of simplifying it.

I have been particularly impressed by the writings of Maurice Merleau‐Ponty, whose thinking I have found inspiringly open‐ended and optimistic. He is a truly poetic philosopher, whose expressions often possess the magic of art. His philosophy has made me understand the chiasmatic way in which the mental and the material worlds intertwine, and that view has opened up new ways of understanding artistic and architectural phenomena. My phenomenological thinking began with an interest in the senses and this led me to critique the hegemony of vision in western culture. This dominance already emerged in Greek philosophy, and has been dramatically accelerated by technology, especially writing and mechanical printing, as Walter J Ong has convincingly suggested in Orality and Literacy.8

After several decades of design work, thinking and writing, I am convinced that the most important sense in architectural experience is not vision, but the existential sense, our sense of self. We exist in ‘the flesh of the world’, to use a notion of Merleau‐Ponty, and architecture gives us our foothold in this very flesh.9 I have also become convinced that peripheral and unfocused perceptions and the understanding of the nature of the human existential reality are more important in architecture than our focused percepts. The continuum of memory, perception and imagination is also more essential than isolated sensations. Simply, focused vision makes us outsiders, whereas embracing peripheral and diffuse perceptions turn us into insiders and participants. This view makes the formal and geometric dominance in architectural theory and education questionable in comparison with an existential, experiential and atmospheric understanding.

In 2010, while working on the translation of two books of mine from English into Italian, Matteo Zambelli, architect and professor, suggested to me the idea of compiling a selection of excerpts of my writings in an encyclopaedic form, organized alphabetically on the basis of keywords identifying the contents of the selected chapters. As I tend to write in fragments, or semi‐autonomous paragraphs, instead of aspiring to forge a seamlessly continuous narrative, I immediately accepted the idea. By the time of our conversation, nearly nine years ago, I had published around 45 books and some 350 essays, prefaces and interviews, mostly on experiential and philosophical views of architecture and the arts (several of them through John Wiley & Sons, London), I felt that there would be enough material for a book based on Matteo's idea. At the same time that the idea of an ‘encyclopaedia’ of my writings sounded somewhat pretentious, it also seemed to project a relaxed attitude in regarding individual essays as mere material for a previously unmeditated entity.

The book was published in Italian by Pendragon, Bologna, in 2011, as Juhani Pallasmaa, Lampi di pensiero. Fenomenologia della percezione in architettura, edited by Mauro Fratta and Matteo Zambelli. Now, at the time of writing the preface for the largely expanded English version of the book, the total number of my books is over 60, and I must have published well over 400 articles and essays. The number of entries in this English edition of Inseminations has likewise roughly been doubled. As students today tend to read short fragments rather than full essays or entire books, a collection of condensed chapters on distinct themes could well be attractive to student readers.

My way of thinking and writing is to focus on a subject matter or view point at a time, record my observations, thoughts and associations on that subject and move on to the next view point or theme of my interest, related to the main topic. My writing process is largely self‐generative, and the ideas emerge through the act of writing itself. The fact that most of my essays are originally written as lectures to be illustrated with a great number of associative images following a visual logic of their own has further supported the additive inner structure of my writings. As a result of my manner of writing, the essays are essentially collaged chapters, and I frequently keep moving the various 'elements' around during the writing process. Usually, I also use a number of quotes, which further emphasize the collage character of my texts. The primary reason for the extensive use of quotes is to place my thoughts in a continuum of thinking, instead of presenting ideas as a personal and independent views of mine. Besides, I do not believe in grand truths or theories, I rather place my confidence in the sincerety of momentary views and situational observations. Observations and ideas are bound to depend on one's point of viewing (a point in the evolution of thought in that specific area of thinking), and thus observations and arguments change in accordance with changes in the point of observation. Usually, I do not agree with myself for too long.

The art forms of collage, compilation, assemblage and montage – the syntax of cinematic expression – have long been close to my way of thinking and aesthetic sensibility. The art form of collage is based on an internal dialogue between the parts that give new meanings to each other, which however continue to posses some degree of autonomy and identity of their own. This complex interaction projects unexpected meanings to the entity. Often the collaged image, as well as piece of writing, consist of conflicts and irreconcilabilities, and unresolved juxtapositions. I deliberately seek internal conflicts in my writings. As a consequence of these aspirations, various parts of my essays can fairly easily be disconnected from the continuity of the text and presented as autonomous statements, credos, or propositions.

Real encyclopaedic entries are written around singular concepts, themes, and subject matters, and the entry revolves cohesively around that very topic. Breaking essays into pieces in accordance with their specific contents, and giving them new title words is a reverse process. As a consequence, most of the fragmented chapters could just as well be classified differently and characterized by alternative keywords. So, this 'encyclopaedia' of my writings is bound to be a quasi‐encyclopedia, one of many alternative compilations.

When writing with a literary ambition, such as an essay, the intensity of argumentation intentionally varies; there are parts that have a particular weight, embedded in paragraphs of lesser significance and density of content. The separation of ideas from their overall context naturally intensifies the density of the compilation of the separated chapters, as the literary rhythm is lost. The isolation of chapters also tends to give them a somewhat aphoristic ambience and a forced significance, which may not have been the tone of the excerpt in its original context.

It should also be noted that all excerpts are given in their original published form, without eliminating repetitions.

•

Thanks to the publisher, Paul Sayer, and the copy‐editor, Nora Naughton.

I want to thank especially Matteo Zambelli for his idea on an encyclopaedic compilation of a score of my writings, and his arduos work in restructuring a huge sampling of my thoughts. The dismantling of my own writings would have been psychologically impossible for me. In this unexpected encyclopaedic context, I tend to read the various entries from a distance, as if they were actually written by someone else. Even in a normal writing process, the personal identification and intimacy of the text keeps changing, and the measure of its finiteness is when it does not feel like yours any more, and it survives independently of you.

13 June 2019

Notes

1

Gaston Bachelard,

The Poetics of Space

, Boston: Beacon Press, 1969.

2

Juhani Pallasmaa, ‘Geometry of Feeling: A look at the Phenomenology of Architecture. Part 1’,

Arkkitehti: The Finnish

Architectural Review

3:1985, 44–49.

3

JH van den Berg,

The Phenomenological Approach in Psychology

(1955), as quoted in Bachelard, op. cit., XXIV.

4

Semir Zeki,

Inner Vision – An Exploration of Art and the Brain

, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1999, 2.

5

David Seamon, Arthur Zajonc, editors,

Goethe's Way of Science

, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1998, 2.

6

Fernando Pessoa,

The Book of Disquiet

, New York: Pantheon Books, 1991, 1.

7

Joseph Brodsky, ‘Less Than One’, in Id.,

Less Than One

, New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1998, 17.

8

Walter J Ong,

Orality & Literacy – The Technologizing of the World

, London and New York: Routledge, 1991.

9

Maurice Merlau‐Ponty describes the notion of the flesh in his essay ‘The Intertwining – The Chiasm’, in Id.,

The Visible and the Invisible

, Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1992.

A

An Artwork is…

→ forgetting

Embodied Experience and Sensory Thought ‐ Lived Space in Art and Architecture (2006)

Rainer Maria Rilke, one of greatest poets of all times, gives a memorable description of the utter difficulty of creating an authentic work of art and of its density and condensation, reminiscent of the core of an atom. ‘For verses are not, as people imagine, simply feelings…, they are experiences. For the sake of a single verse, one must see many cities, men and things, one must know the animals, one must feel how the birds fly and know the gesture with which the little flowers open in the morning’.1 The poet continues his list of necessary experiences endlessly. He lists roads leading to unknown regions, unexpected encounters and separations, childhood illnesses and withdrawals into the solitude of rooms, nights of love, screams of women in labour, and being beside the dying. But even all of this together is not sufficient to create a line of verse. One has to forget all of this and have the patience to wait for their return. Only after all our life experiences have turned to the own blood within us, ‘not till then can it happen that in a most rare hour the first word of a verse arises in their midst and goes forth from them’.2

Aestheticization

→ elementarism; eyes; experience has a multi‐sensory essence; newness

The Existential Wisdom: Fusion of Architectural and Mental Space (2008)

In our materialist and digital age, buildings are regarded as aestheticized objects and judged primarily by their visual characteristics. In fact, the dominance of vision has never been stronger than in the current era of the technologically expanded eye and industrially mass‐produced visual imagery, the ‘unending rainfall of images’,3 as Italo Calvino appropriately describes the present cultural condition. In today's media culture, architecture has been turned into an artform of image and instant gratification. The rapid triumph of computerized design methods over sketching by hand, and full involvement of the body in the design process, has brought about yet another level of detachment from embodiment and immediate sensory contact.

The consumer culture of today has a blatantly dualistic attitude towards the senses and human embodied existence at large. On the one hand, the fundamental fact that, experientially, we exist in the world through the senses and cognitive processes is neglected in the established views of the human condition. This attitude is also directly reflected in educational philosophies as well as practices of daily life; in our cult of physical beauty, strength and virility we live increasingly bodiless lives. On the other hand, our culture has developed an obsessively aestheticized and eroticized cult of the body and we are increasingly manipulated and exploited through our senses. The body is regarded as the medium of identity and self‐presentation as well as an instrument of social and sexual appeal. Current consumer capitalism has even developed a ‘new technocracy of sensuality’ and shrewd strategies of ‘multi‐sensory marketing’ for the purposes of sensory seduction and product differentiation. This commercial manipulation of the senses aims at creating a state of ‘hyperaesthesia’ in the consumer.4 Artificial scents are added to all kinds of products and spaces, whereas muzak conditions the shopper's mood. We have undoubtedly entered an era of manipulated and branded sensations. Signature architecture, aimed at creating eye‐catching, recognizable and memorable visual images, or architectural trademarks, is also an example of sensory exploitation, the attempt ‘to colonize by canalizing the “mind space” of the consumer’.5

We are living in an age of aestheticization without being hardly aware of it. Everything is aestheticized today; consumer products, personality and behaviour, politics, and ultimately even war. Formal and aesthetic qualities have also in architecture replaced functional, cultural and existential criteria. The appearance of things is more important than their essence. An aestheticized surface appeal has displaced meaning and social significance. The social idealism and compassion that gave modernism its sense of optimism and empathy have frequently been replaced by formalist retinal rhetoric. The lack of ideals, visions and compassion is equally clear in today's pragmatic and egoistic politics.

Amplifiers of Emotions

→ Emotions; Emotions and Creative Thought; Microcosms; Spatialized Memories;

Selfhood, Memory and Imagination: Landscapes of Remembrance and Dream (2007)

In addition to being memory devices, landscapes and buildings are also amplifiers of emotions; they reinforce sensations of belonging or alienation, invitation or rejection, tranquillity or despair. A landscape or work of architecture cannot, however, create feelings. Through their authority and aura, they evoke and strengthen our own emotions and reflect them back to us as if these feelings of ours had an external source. In the Laurentian Library in Florence I confront my own sense of metaphysical melancholy awakened and reflected back by Michelangelo's architecture. The optimism that I experience when approaching the Paimio Sanatorium is my own sense of hope evoked and strengthened by Alvar Aalto's optimistic architecture. The hill of the meditation grove at the Forest Cemetery in Stockholm, for instance, evokes a state of longing and hope through an image that is an invitation and a promise. This architectural image of landscape simultaneously evokes remembrance and imagination as the composite painted image of Arnold Böcklin's ‘Island of Death’. All poetic images are condensations and microcosms.

‘House, even more than the landscape, is a psychic state’, Bachelard suggests.6 Indeed, writers, film directors, poets and painters do not just depict landscapes or houses as unavoidable geographic and physical settings of the events of their stories; they seek to express, evoke and amplify human emotions, mental states and memories through purposeful depictions of settings, both natural and man‐made. ‘Let us assume a wall: what takes place behind it?’, asks the poet Jean Tardieu,7 but we architects rarely bother to imagine what happens behind the walls we have erected. The walls conceived by architects are usually mere aestheticized constructions, and we see our craft in terms of designing aesthetic structures rather than evoking perceptions, feelings and fantasies.

Animal Architecture

→ architecture and biology; biophilic beauty

Our established view of architecture and its history is surprisingly limited. Almost all books and courses on architectural history begin with Egyptian architecture, i.e. roughly 5500 years ago. The lack of interest in the origins of human constructions for inhabitation or cosmological and ritual purposes is truly surprising even considering the fact that material remains of earliest constructions of man would not exist. We know that domestication of fire took place about 700,000 years ago, and the centring, focusing and organizing impact of fire is already an architectural ingredient. In fact, the earliest architectural theorist, the Roman Vitruvius Pollio, acknowledges this fact in De Architectura libri decem (Ten Books on Architecture), which he wrote during the first decade of Pax Augusta, c. 30–20 BC. Most treatises associate the origins of architecture in tectonic construction, in other words, assembled masonry or wood structures or moulded clay and mud constructions. However, there is very little doubt in the assumption that human architecture originates in woven fibre structures. Architectural anthropology, a rather recent field of research, studies the origins of certain ritualistic and spatial patterns in the building behaviour of apes.8

Also, the countless vernacular building traditions of the world with their impressive features of adaptation to prevailing local conditions, such as climate and available materials, were not much thought about until Bernard Rudofsky's exhibition Architecture Without Architects at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1964.9 Anthropological studies have revealed the cultural, symbolic, functional and technical refinements of the unselfconscious processes of construction mediated by illiterate and embodied traditions. However, vernacular traditions still remain as a curiosity in architectural studies, although the deepening of research in the sustainability of human settlements and ways of constructions will certainly awake interest in this neglected area of human building culture.

Animal constructions serve the same fundamental purposes as human constructions; they alter the immediate environment for the benefit of the species by increasing the level of order and predictability of the habitat and improving the probability of survival and procreation. As we know, animal constructions are surprisingly varied. Some degree of building behaviour is practised throughout the entire animal kingdom, and skilful building species are scattered throughout the phyla from protozoa to primates. Pockets of special architectural skill can be found among birds, insects and spiders. It is thought-provoking to realize that the constructions of higher animals are among the least ingenious. Apes, for example, only construct a temporary shelter each night – although there seems to be more organization and skill than we have observed so far – as compared with the termite metropolis of millions of inhabitants which may be utilized for centuries.

The interest in animal architecture among architects and architectural scholars has remained totally anecdotal although inspiring documentation on animal constructions has existed since Reverend John George Wood's remarkable treatise Homes Without Hands published in 1865.10 Karl von Frisch's Animal Architecture of 197411 was instrumental in re‐awaking my own by then already forgotten childhood fascination in building activities of animals. Michael H Hansell's books and exhibition in Glasgow in 1999 have provided scientific ground on the functioning principles as well as materials and ways of constructing among animals.

The book La Poétique de l'espace (1958) by the French philosopher of science and poetic imagery has been one of the most influential books in the recent theorizing of architecture surprisingly includes a chapter on nests.12 He quotes the view of Ambroise Paré written in 1840: “The enterprise and skill with which animals make their nests is so efficient that it is not possible to do better, so entirely do they surpass all masons, carpenters and builders; for there is not a man who would be able to make a house better suited to himself and to his children than these little animals build for themselves. This is so true, in fact, that we have a proverb according to which men can do everything except build a bird's nest”.13

In relation to the size of their builders many animal constructions exceed the scale of human constructions. Others are constructed with a precision unimaginable in human construction. Artifact‐building animals teach us that the organization of even simple animal life is complex and subtle. Close studies by scanning electron microscope (SEM) reveal mind‐boggling refinements of structures in a scale invisible to the human eye and totally beyond the capabilities of human builders, such as the microscopic structural ingenuities of spider or caddis fly larva constructions.

Animals frequently use the same construction materials and construction methods as vernacular human cultures. Regardless of the usually great differences in scale, similarities on a formal level are often surprising. The clay structures of various swallows and wasps resemble structures of American Indians. In traditional African cultures, woven huts often appear as enlarged bird's nests or even constructions of certain fish species. Beaver's curved dam walls fight the pressure of water in the same way as some of our largest and most advanced dams. A tiny butterfly larva may protect its case with a dome assembled of its own larva hair, echoing the geometry of Buckminster Fuller's geodesic structures which are among the most efficient human constructions in their ratio of enclosed volume to weight ever conceived. A Green Building research project (1990) by Future Systems utilizing a jar‐like external shape and a system of natural ventilation strikingly evokes the internal nest shape and automated air‐conditioning system of Macroterms bellicosus termites, one of the finest constructions in the animal kingdom. I have myself paired such similar images, but they are, of course, bound to remain on the level of the similarity of appearance only. These comparisons can be interesting and stimulating but they cannot teach us anything essential, I believe.

So far, the institution that has made the most serious research on the internal logic of certain animal constructions and their adaptability in human architecture is the Institute of Lightweight Structures at the University of Stuttgart directed by Frei Otto, a notable architect and constructor. These studies have focused on net and pneumatic structures.14

After mentioning some parallels, I would like to point out certain significant differences in animal and human architecture. Let me begin with the time factor. Animal building processes are the result of immensely long evolutionary processes, whereas our own architectural history is very short in comparison.

Spiders and their web‐building skills have evolved, perhaps, during some 300 million years; The Economist published high‐resolution X‐ray micro‐tomograph images of 312‐ million‐year‐old fossilized arachnids that had eight legs but lacked spinnerets and presumably could not produce silk. When such periods of evolutionary development are compared with the meagre couple of million years of human development since Homo erectus stood up on two legs, we can easily expect animal building skills to exceed ours. There were surely animal architects on earth for tens of millions of years before Homo sapiens put together his first clumsy structures. As I said earlier, our conventional concepts of architecture are restricted to constructions that have taken place over roughly 5000 years of Western high culture.

Another difference arises from the fact that animal architecture has evolved, and continues to do so, under the laws and control of evolution, whereas human architecture has detached itself from this control mechanism and immediate feedback. Whereas animal structures are continuously tested by the reality of survival, we can, and do, develop absurd architectural ideas without the punishment of natural selection and immediate elimination. As Mies van der Rohe said, we tend to ‘invent a new architecture every Monday morning’. This temporary emancipation from the logic of survival allows us to build totally irrational structures in terms of the real necessities of life. In our ‘Society of the Spectacle’, as Guy Debord calls the current era, architecture has often turned into sheer fashion, representation, aestheticization and visual entertainment. The punishment is delayed, of course, because the false models are not eliminated and, consequently, the causal absurdity becomes a concern for the future generations. It is a sad fact that our architecture keeps developing largely without the test of reality.

Sverre Fehn, the great Norwegian architect, once said to me in a private conversation: ‘The bird nest is absolute functionalism, because the bird is not conscious of its death’.15 This aphoristic and cryptic argument contains a significant truth. Ever since we became conscious of ourselves and our existence in the world, all our actions and constructions, material and mental, are bound to be engaged in the metaphysical enigma of existence itself. We cannot achieve perfect functionality and performance in our dwellings because our houses and other structures have their metaphysical, representational and aesthetic dimensions which necessarily compromise performance in the strict terms of biological survival. These metaphysical concerns and aspirations frequently overrule the requirements of biological and ecological survival.

Animal constructions are structurally efficient, and natural selection has gradually optimized both the forms of structures and the use of materials. The hexagonal cell structure of the bee with its specific angles is the mathematically optimum structure for storing honey. The vertically suspended cell wall of the bee with its two layers of cells, built back‐to‐back with one‐half a cell's shift in the position of the cell walls, to create a continuous three‐dimensional folded structure made of pyramidal units at the boundary surface, is structurally ingenious.

The inner cell of the abalone is twice as tough as human‐made high‐tech ceramics; instead of breaking, the shell deforms under stress like a metal. Mussel adhesive works underwater and sticks to anything, whereas rhino horn repairs itself although it contains no living cells. All these miraculous materials are produced in body temperatures without toxic by‐products and they return back to the cycle of nature.

The extraordinary strength of spider drag line is the most impressive example of the technical miracles of evolutionary processes. None of the man‐made metals or high‐strength fibres of today can come close to the combined strength and energy‐absorbing elasticity of spider drag line. The tensile strength of the line spun by the spider is more than three times that of steel. The elasticity of spider drag line is even more amazing; its extension at break point is 229% as compared with the 8% of steel. The spider silk consists of small crystallites embedded in a rubbery matrix of organic polymer – a composite material developed, perhaps, a couple of hundred million years before our current age of composite materials.

Two thousand years ago, wasps taught the Chinese how to make paper, and the nesting chambers of potter wasps are believed to have served as models of clay jars for the American Indians. The Chinese learned 4600 years ago, how to use the fine silk line spun by the larva of the silk moth, and even today we are using several million kilograms of raw silk annually. In addition to being used as material for fine cloth, silk thread was earlier used to produce fishing rods and strings of musical instruments.

How could we take advantage of the inventions of animals today and what lessons could we learn from a study of animal building behaviour?

The slow evolution of animal artefacts can be compared with the processes of tradition in traditional human societies. Tradition is a force of cohesion that slows down change and ties individual invention securely to patterns of tradition, established through endless time and the test of life. It is this interaction of change and rigorous testing by forces of selection that is lost in human architecture of the industrial era. We believe in individuality, novelty and invention. Human architecture evolves more under forces of cultural and social values than forces of the natural world.

The role of aesthetic choice is important, as it is a guiding principle in human structures. Whether aesthetic choice exists in the animal world is arguable, but it is unarguable that the principle of pleasure guides even the lowest animal behaviour and the transformation of physical pleasure to aesthetic pleasure could well be rather unnoticeable. Regardless of the question of the intentionality of beauty in animal constructions the beauty of superb performance and causality of animal architecture gives pleasure to the human eye and mind.

I will give one example of the human use of animal inventions reported in The Economist.16 David Kaplan and his colleagues at Tufts University have succeeded to extend the range of properties of spider silk beyond those found in nature. By shuffling the order and number of the hydrophilic, hydrophobic and structure – organizing sections of DNA, and then recruiting bacteria to turn the resulting artificial genes into proteins, the research team has turned out about two dozen novel forms of silk. Some of the tougher and more water‐resistant forms of silk might be employed to impregnate synthetic fibres and lightweight materials called hydrogels to make them stronger and waterproof. The more resilient materials that resulted could then be used to coat and toughen surfaces, strengthen the biologically friendly plastics employed in surgery, and create strong, lightweight components for use in aircraft.

Material sciences which also develop novel materials also for architectural purposes that can be automatically be responsive to prevailing environmental conditions, such as temperature, moisture and light, in the way that live tissue adjusts its functions, are becoming important in the scientific development of human building. Analogies and models from the biological world can be decisive, as in the case of the development of self‐cleaning glass, based on observations of the surface structure of the giant water lily and practically invisible nano‐technology.

It is also becoming increasingly essential that our own constructions are seen in their anthropological, socio‐economic and ecological frameworks, in addition to the traditional aesthetic sphere of the architectural discipline. It is equally important that our aesthetic understanding of architecture is expanded to the biocultural foundations of human behaviour and construction. The field of bio‐psychology is an example of such an extension. As builders, we could learn from studying the gradual and slow development and adaptation of animal constructions over the course of endless time.

Animal constructions open up an important window on the processes of evolution, ecology and adaptation. Ants have the biggest biomass and as a consequence of their skills in adapting to a wide variety of environmental conditions they are the most numerous and widespread of animals, including man. They are among the most highly social of all creatures, and the study of ants has produced insights into the origins of altruistic behaviour.

Architecture and the Human Nature: Searching for a Sustainable Metaphor (2011)

I do not support any romantic bio‐morphic architecture. I advocate an architecture that arises from a respect of nature in its complexity, not only its visual characteristics, and from empathy and loyalty to all forms of life and a humility about our own destiny.

Indeed, architecture cannot regress; all life forms and strategies of nature keep developing and refining. The magnitude of our problems calls for extremely refined, responsive and subtle technologies.

It is becoming evident that we have distanced ourselves too far from nature with grave consequences. The research of the Finnish allergiologist Tari Haahtela has shown convincingly that many of the so‐called ‘civilization diseases’, such as all allergies, diabetes, depression, many types of cancer, and even obesity, are consequences of living in too sterile and ‘artificial’ environments. We have destroyed the natural bacterial habitats in our intestines. This specialist in allergies tells us that he has never met an allergy patient ‘with earth under his fingernails’.17

Anonymity

→ humility; personality cult

Voices of Tranquility: Silence in Art and Architecture (2011)

In today's consumerist culture we are misled to believe that the qualities of art and architecture arise from expression of the artist's or architect's persona. However, as the philosopher Maurice Merleau‐Ponty writes: ‘We do not come to look at a work of art, we come to look at the world according to it’.18 In a late interview Balthus, one of the greatest figurative painters of last century, makes a thought‐provoking comment on artistic expression: ‘Modernity, which began in the true sense with the Renaissance, determined the tragedy of art. The artist emerged as an individual and the traditional way of painting disappeared. From then on, the artist sought to express his inner world, which is a limited universe: he tried to place his personality in power and used paintings as a means of self‐expression. But great painting has to have universal meaning. This is sadly no longer so today and this is why I want to give painting back its lost universality and anonymity, because the more anonymous painting is, the more real it is’.19 In his work and teaching, the dignified Finnish designer, Kaj Franck, also sought anonymity; in his view the designer's persona should not dominate the experience of the object. In my view, the same criterium applies fully to architecture; profound architecture arises from facts, causalities and experiences of life, not from personal artistic inventions. As Alvaro Siza, one of the greatest architects of our time argues: ‘Architects do not invent anything, they just transform conditions’. In a television interview in 1972, Alvar Aalto made an unexpected confession: ‘I don't think there's so much difference between reason and intuition. Intuition can sometimes be extremely rational. […] It is the practical objectives of constructions that give me my intuitive point of departure, and realism is my guiding star. […] Realism usually provides the strongest stimulus to my imagination’.20

In my own work, I have always wanted to pull myself away from the work when it is finished. The work needs to express the beauty of the world and human existence, not any idiosyncratic ideas of mine. This call for anonymity does not imply lack of emotion and feeling. Meaningful design re‐mythicizes, re‐animates and re‐eroticizes our relationship with the world. I wish my designs to be sensuous and emotive, but not to express my emotions.

Architectural Courtesy

→ verbs vs nouns

Artistic Generosity, Humility and Expression: Reality Sense and Idealization in Architecture (2007)

In addition to an ‘aesthetic withdrawal’ and ‘politeness’, I have spoken of an ‘architectural courtesy’ referring to the way a sensuous building offers gentle and subconscious gestures for the pleasure of the occupant: a door‐handle offers itself courteously to the approaching hand, the first step of a stairway appears exactly at the moment you wish to proceed upstairs, and the window is exactly where you wish to look out. The building is in full resonance with your body, movements and desires.

Architecture and Being

→ being in the world; senses

Artistic Generosity, Humility and Expression: Reality Sense and Idealization in Architecture (2007)

I could tell of countless spaces and places that I have encapsulated in my memory and that have altered my very being. I am convinced that every one of you can recall such transformative experiences. This is the power of architecture; it changes us, and it changes us for the better by opening and emancipating our view of the world.

Skilfully designed buildings are usually expected to direct and channel the occupant's experiences, feelings and thoughts. In my view, this attitude is fundamentally wrong; architecture offers an open field of possibilities, and it stimulates and emancipates perceptions, associations, feelings and thoughts. A meaningful building does not argue or propose anything; it inspires us to see, sense and think ourselves. A great architectural work sharpens our senses, opens our perceptions and makes us receptive to the realities of the world. The reality of the work also inspires us to dream. It helps us to see a fine view of the garden, feel the silent persistence of a tree, or the presence of the other, but it does not indoctrinate or bind us.

Selfhood, Memory and Imagination: Landscapes of Remembrance and Dream (2007)

In addition to practical purposes, architectural structures have a significant existential and mental task; they domesticate space for human occupation by turning anonymous, uniform and limitless space into distinct places of human significance, and, equally importantly, they make endless time tolerable by giving duration its human measure. As Karsten Harries, the philosopher, argues: ‘Architecture helps to replace meaningless reality with a theatrically, or rather architecturally, transformed reality, which draws us in and, as we surrender to it, grants us an illusion of meaning. […] We cannot live with chaos. Chaos must be transformed into cosmos’21. ‘Architecture is not only about domesticating space. It is also a deep defence against the terror of time’, he states in another context.22

Altogether, environments and buildings do not only serve practical and utilitarian purposes, they also structure our understanding of the world. ‘The house is an instrument with which to confront the cosmos’, as Gaston Bachelard states.23 The abstract and undefinable notion of cosmos is always present and represented in our immediate landscape. Every landscape and every building are a condensed world, a microcosmic representation.

Architecture and Biology

→animal architecture; biophilic beauty; tradition

Architecture as Experience: Existential Meaning in Architecture (2018)

Profound architects have always intuitively understood that buildings structure, re‐orient and attune our mental realities. They have also been capable of imagining the experiential and emotive reactions of the other. The fact that artists have intuited mental and neural phenomena, often decades before psychology or neuroscience has identified them, is the subject matter of Jonah Lehrer's thought‐provoking book Proust Was a Neuroscientist.24 In his pioneering book Survival through Design (1954), Richard Neutra acknowledges the biological and neurological realities, and makes a suggestion that is surprising for its time: ‘Our time is characterized by a systematic rise of the biological sciences and is turning away from oversimplified and mechanistic views of the 18th and 19th centuries, without belittling in any way the temporary good such views may have once delivered. An important result of this new way of regarding this business of living may be to bare and raise appropriate working principles and criteria for design’.25 Later he even professed: ‘Today design may exert a far‐reaching influence on the nervous make‐up of generations’.26 Thanks to electronic instruments such as the fMRI scanner, today we know that this is the case. Also, Alvar Aalto intuited the biological ground of architecture in his statement: ‘I would like to add my personal, emotional view, that architecture and its details are in some way all part of biology’.27 The direct impact of settings on the human nervous system and brain has been proven by research in today's neuroscience. ‘While the brain controls our behaviour and genes control the blueprint for the design and structure of the brain, the environment can modulate the function of the genes and, ultimately, the structure of the brain. Changes in the environments change the brain, and therefore they change our behaviour. In planning the environments in which we live, architectural design changes our brain and our behavior’.28 This statement by Fred Gage, neuroscientist, leads to the most crucial realization: when designing physical reality, we are, in fact, also designing experiential and mental realities, and external structures condition and alter internal structures. We architects unknowingly operate with neurons and neural connections. This realization heightens the human responsibility in the architect's work. I, myself, used to see buildings as aestheticized objects, but for three decades now, architectural images have been primarily mental images, or experiences of the human condition and mind. I have also gradually come to understand the significance of the designer's empathic capacity, the gift to simulate and empathize with the experience of ‘the little man’, to use Alvar Aalto's notion.29

Empathic Imagination: Embodied and Emotive Simulation in Architecture (2016)

The Paimio Sanatorium, designed in 1929–1933 by Alvar Aalto, is one of the landmarks of Functionalist architecture, but it is also an example of the architect's empathic attitude and skill. This is what Aalto writes about his design process: ‘I was ill at the time I received the commission, and was able to experiment a little with what it means to be really incapacitated. It was irritating to have to lie in a horizontal position all the time, and the first thing I noticed was that the rooms are designed for people in a vertical position, not for those who have to lie in bed all the time. Like flies around a lamp, my eyes turned towards the electric light, and there was no inner balance, no real peace in the room that could have been designed specially for a sick, bedridden person. I therefore tried to design rooms for weak patients that would provide a peaceful atmosphere for people who have to stay in a horizontal position. Thus, I decided against air conditioning because the entering current of air feels unpleasant to the head, and in favor of fresh air heated ever so slightly between the two window panes of the double glazing. I cite these examples to show how incredibly small details can be used to alleviate people's suffering. Here is another example, a washbasin. I strove to design a basin in which the water does not make a noise. The water falls on the porcelain sink at a sharp angle, making no sound to disturb the neighboring patient, as in the physically or mentally weakened condition the impact of the environment is heightened’.30 Aalto often spoke of ‘the little man’ as the architect's real client, and he concluded that we should always design for ‘the man at his weakest’.31 These are examples of an empathic imagination in opposition to formalist imagination.

Architecture as Experience

→ experience has a multi‐sensory essence; reconciling

Architecture as Experience: Existential Meaning in Architecture (2018)

The phenomenon of architecture has also been approached through subjective and personal encounters in poetic, aphoristic or essayistic ways, as in the writings of many of the leading architects from Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier to Alvar Aalto and Louis Kahn and further to Steven Holl and Peter Zumthor. In these writings, architecture is approached in a poetic and metaphorical manner, without any ambitions or qualifications as scientific research. These writings usually arise from personal experiences, observations and beliefs, and they approach architecture as a poetic encounter and a projection of life, and their ambition is to be experientially true. I must personally confess that these personal, and often confessional accounts, have valorized the holistic, existential and poetic essence of architecture to me more than the theoretical or empirical studies that claim to satisfy the criteria of science.

Historically there are three categories of seeking meaning in human existence: religion (or myth), science and art, and these endeavours are fundamentally incomparable with each other. The first is based on faith, the second on rational knowledge and the third on existential and emotive experiences. The poetic, experiential and existential core of art and architecture has to be confronted, lived and felt rather than understood and formalized intellectually. There are certainly numerous aspects in construction, in its performance, structural reality, formal and dimensional properties, as well as distinct psychological impacts, that can be, and are being, studied ‘scientifically’, but the experiential mental and existential meaning of the entity can only be encountered and internalized.

During the past few decades, an experiential approach, based on phenomenological encounters and first‐person experiences of buildings and settings, has gained ground. This thinking is initially based on the philosophies of Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, Maurice Merleau‐Ponty, Gaston Bachelard and many other philosophical thinkers. The phenomenological approach, which acknowledges the significant role of embodiment, was introduced into the architectural context by such writers as Steen Elier Rasmussen, Christian Norberg‐Schulz, Charles Moore, David Seamon, Robert Mugerauer and Karsten Harries, for instance. I also believe that the book Questions of Perception of 1994 by Steven Holl, Alberto Pérez‐Gómez and myself helped to spread this manner of thinking especially in schools of architecture internationally.

The poetic and existential dimension of architecture is a mental quality, and this artistic and mental essence of architecture emerges in the individual encounter with and experience of the work. In the beginning of his seminal book of 1934, Art as Experience, John Dewey, the visionary American pragmatist philosopher argues: ‘In common conception, the work of art is often identified with the building, book, painting, or statue in its existence apart from human experience. Since the actual work of art is what the product does with and in experience, the result is not favorable to understanding. […] When artistic objects are separated from both conditions of origin and operation in experience, a wall is built around them that renders almost opaque their general significance, with which esthetic theory deals’.32 Here, the philosopher connects the condition of making a piece of art and its later encounter by someone else, as in both cases the mental and experiential reality dominates and the work exists ‘nakedly’ as a human experience. The philosopher suggests that the difficulties in understanding artistic phenomena arise from the tradition of studying them as objects outside of human consciousness and experience. Dewey writes further: ‘By common consent, the Parthenon is a great work of art. Yet, it has aesthetic standing only as the work becomes an experience for a human being. […] Art is always the product in experience of an interaction of human beings with their environment. Architecture is a notable instance of the reciprocity of the results in this interaction. […] The reshaping of subsequent experience by architectural works is more direct and more extensive than in the case of any other art. […] They not only influence the future, but they record and convey the past’.33