Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Eland Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

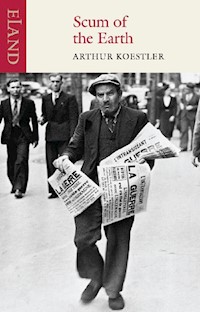

At the beginning of the Second World War, Koestler was living in the south of France working on Darkness at Noon. After retreating to Paris he was imprisoned by the French as an undesirable alien even though he had been a respected crusader against fascism. Only luck and his passionate energy allowed him to escape the fate of many of the innocent refugees, who were handed over to the Nazis for torture and often execution. Scum of the Earth is more than the story of Koestler's survival. His shrewd observation of the collapse of French determination to resist during the summer of 1940 is an illustration of what happens when a nation loses its honour and its pride.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 451

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Scum of the Earth

ARTHUR KOESTLER

To the memory of my colleagues, the exiled writersof Germany who took their lives when France fell:

Walter Benjamin, Carl Einstein,Walter Hasenclever, Otto Pohl,Ernst Weiss

And for Paul Willert, without whose help thisbook could not have been written

PREFACE TO THE 1955 EDITION

“Scum of the Earth” was the first book that I wrote in English. It was written in January-March 1941, immediately after I had escaped from occupied France to England. My friends were either in the hands of the Gestapo, or had committed suicide, or were trapped, seemingly without hope, on the lost Continent. The agony of the French collapse was still reverberating through my mind as a scream of terror echoes in one’s ear. Within the previous four years I had been imprisoned in three different countries: in Spain, under sentence of death, during the Civil War: as a political suspect and undesirable alien in France; finally, having escaped to England with false papers at the height of the Fifth Column scare, I was locked up, pending investigation, in Pentonville Prison. The book was written in the blacked-out London of the night-blitz, in the short breathing space between Pentonville and enlistment in the Pioneer Corps. Not only time was short, but money too. Having lost all my possessions in France, I arrived in England penniless, and had to live on the advance which the original publisher of the book paid me: five pounds a week during ten weeks, plus an additional ten pounds on delivery of the manuscript, minus the cost of hiring a typewriter and sundry other expenses which were deducted from the weekly five pounds.

Re-reading the book for the first time after thirteen years, I find these outer and inner pressures reflected in its apocalyptic mood, its spontaneity and lack of polish. Some pages now appear insufferably maudlin: others are studded with clichés which at the time, however, seemed original discoveries to the innocent explorer of a new language-continent; above all the text betrays the fact that there had been no time for correcting proofs. To remedy these faults would mean to re-write the book, and that would be a pointless undertaking—for, if the book has any value, it lies in its documentary period character. I have confined myself to correcting only the most glaring gallicisms, germanisms and grammatical errors—and to throwing out adjectives and similes at a set rate of one in five.

The period character of the book is particularly evident in its political outlook. It is the romantically and naïvely Leftish outlook of the pink thirties. I had been a member of the Communist Party for seven years; I had left it in disgust and despair in 1938, but certain illusions about Soviet Russia and “the international solidarity of the working classes as the best guarantee of peace” lingered on, and are reflected throughout the book. That again is typical of the time—a time when my late friend George Orwell, who was of a less romantic disposition that I, could write that:

“… the war and the revolution are inseparable… We know very well that with its present social structure England cannot survive…. We cannot win the war without introducing Socialism. Either we turn this war into a revolutionary war or we lose it.”1

If all this is dated, other aspects of the story have, alas, remained painfully topical. The sickness of the French body politic, which led to the debacle of 1940, is again threatening to bring disaster to what remains of Europe. Many passages of the book, e.g. the outburst of Marcel, the garage mechanic (p. 56), are textually applicable to the present situation—only the word “Fascism” has to be replaced by its contemporary equivalent, “Totalitarianism.”

To protect the personages who appear in the book from Gestapo persecution, I had to camouflage them. For similar reasons certain episodes had to be passed over in silence. The friends who were hiding me from the French police in Paris (p. 163), and who succeeded in obtaining for me a travelling permit, were the late Henri Membré, secretary of the French PEN Club, and that admirable woman of letters, Adrienne Monnier. The real name of “Père Darrault” (pp. 198 ff.), is Père Pieprot, O.D., at present Secretary General of the International Congress for Criminology. “Albert” is the German-American author Gustav Regler. Among the various characters in Hut No. 33 of the concentration camp at Le Vernet, who are only referred to by initial letters, were the German Communist leaders Paul Merker and Gerhardt Eisler. Finally, there is “Mario,” about whom I must speak at some length.

Mario’s real name is Leo Valliani. He was born in 1909 at Fiume. He was seventeen, and a student of Social History, when Mussolini out-lawed the Italian Opposition and suppressed civil liberties. Valliani joined the only underground opposition party then existing in Italy: the Communists. At the age of nineteen he was arrested and deported for one year to the island of Ponza. After his release he went back to the Communist underground as a member of its committee for the Istria region. Arrested again at the age of twenty-one, he was sentenced to twelve years’ imprisonment. Of these he served six years: the other half was spared him by an amnesty. In 1936 he escaped to Paris, where he edited QueFaire? a political monthly which represented the last attempt to create a democratic opposition within the Communist International. He broke with Communism after the Stalin-Hitler pact and joined Carlo Rosseli’s movement “Justice and Liberty,” which became during the war the Italian Action Party. In October 1939 he was arrested by the French police and sent to the camp of Le Vernet, where he spent a year. In October 1940 he escaped from Le Vernet to Morocco, where he worked with the French Resistance. After a brief breathing spell in Mexico, he returned in October 1943, with British help, on a secret mission to Italy. He crossed the German lines north of Naples, and after five days reached Rome on foot. He was appointed Secretary of the illegal Action Party, which he represented in the Command of the Italian Resistance. In March-April 1945, he was one of the three members of the Central Insurrectional Committee which organised the rising against the Nazis and ordered Mussolini’s execution. In 1946 he was elected to the Constituent Assembly. Three years later he retired from politics and became a scholar again. He has since published his memoirs of the Italian Resistance and a number of books and essays, ranging from a History of the Socialist Movement to a critical evaluation of the philosophy of Benedetto Croce.

“Mario” has remained my closest friend during the fifteen years since we first met in the concentration camp. As he was still a prisoner in France at the time when I wrote “Scum of the Earth,” not only his name, but also his story, had to be camouflaged; this explains certain minor discrepancies between the biographical data in this preface and in the text.

The narrative ends with my arrival in 1940 in Marseilles, where I joined an escape party of British officers. For security reasons the story of our escape via Oran to Casablanca, then by fishing boat to Lisbon and thus eventually to England, could not be told at the time and there would be no point in enlarging on it to-day. It is an escape story like dozens of others that have been told since, and less eventful than most.

The last stage of this long trek to freedom was Pentonville Prison, where I spent six peaceful weeks in solitary confinement during the later part of the blitz. Most of the time—on the average fifteen to sixteen hours a day—the cell was pitch dark, because the alert usually came with the fading of daylight, and the lights in the cell were then switched off to prevent us presumptive Fifth Columnists from signalling to the raiders.

For the same reason we were not allowed to keep matches in the cell, although we were allowed to keep cigarettes. Fellow prisoners, however, taught me an ingenious method of lighting cigarettes, which I will describe for the benefit of readers who may find themselves in a similar predicament. Take a piece of cotton wool (extracted from filter-tip cigarettes) and roll a shred of silver paper into the shape of a toothpick; take the lighting bulb out of its fitting and insert the silver stick into the socket, holding the cotton wool close. This will cause a short-circuit, and with some luck and skill the cotton wool will catch the spark. If the faint glow of the wool stops before you can touch it to the cigarette, start again. Average duration until success is achieved: one hour. But in the circumstances one has plenty of time on one’s hands, and a cigarette ignited in these conditions acquires additional flavour from the pride of achievement. The silver stick has to be kept very thin, however, otherwise the fuses of the whole wing will blow and you will be put on bread and water.

The second art that I acquired in Pentonville was so-called “Marseilles chess.” It was invented by an elderly Frenchman, with a red scarf round his neck, who taught it to me during exercise hours. In this game, each player in turn makes two moves instead of one—the only restriction being that the first of the two moves should not be a check to the King. To the chess-addict this is a nerve-racking experience which shatters his outlook and upsets all his values. Hitler and the Gestapo have faded into the past, but the memory of Marseilles chess in Pentonville still makes me shudder.

London,September 30, 1954

1 George Orwell: The Lion and the Unicorn, London 1941.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This book was written in January-March 1941, before the German attack on Russia; yet the author sees no reason to modify his observations on the psychological effects of the Soviet-German pact of August 1939, or his opinion on the policy of the Communist Party in France. To smuggle in elements of a later knowledge when describing the mental pattern of people in an earlier period is a common temptation to writers, which should be resisted.

August 1941

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

PREFACE TO THE 1955 EDITION

AUTHOR’S NOTE

AGONY

PURGATORY

APOCALYPSE

AFTERMATH

EPILOGUE

Copyright

AGONY

‘Like the cameo cutter of Herculaneum,who,while the earth cracked and the lava bubbledand it rained ashes, calmly went on carving athis tinyplaque.’

ROBERT NEUMANN By the Waters of Babylon

I

SOME time during the last years of Queen Victoria’s reign, the Prince of Monaco had an anglicized mistress who wanted a bathroom of her own. He built her a villa, with a real bathroom that had parquet flooring, and colour prints of knights in armour and ladies in bustles fed on Benger’s Food adorning all the walls. He built it at a prudent distance from his own residence in Monaco: about fifty miles up the valley of the Vésubie and only ten miles from the Italian frontier, in the parish of Roquebillière, département des Alpes-Maritimes. With the march of time and the dawn of the twentieth century, the refined courtesan became a respectable old rentière, let the bathroom decay, planted cabbage in her garden, and eventually died. For some twenty years the house stood empty and the garden ran wild.

Then, in the late nineteen-twenties, a landslide occurred in the valley of the Vésubie, which destroyed about fifty of the hundred houses of Roquebillière and killed sixty out of its five hundred inhabitants. As a result of this, ground rents in Roquebillière became very low, and in 1929 Maria Corniglion, wife of Corniglion-upon-the-Bridge, talked her husband into buying the villa with the bathroom from the defunct lady’s heirs. Ettori Corniglion was a peasant who still cultivated his five acres of land himself, with a primitive plough and a yoke of oxen, but Maria Corniglion was an enterprising woman who had brought him a respectable dowry. The Corniglions-upon-the-Bridge were well-to-do people—more so than Corniglion-the-Grocer or Corniglion-the-Butcher. Mme. Ettori Corniglion was herself born a Corniglion—for an area extending about twenty miles down the Vésubie from St. Martin one-third of the population were Corniglions. They intermarried frequently, producing a remarkable rate of cripples and idiots, and had the most imposing marble tombstones and family vaults in the graveyards of old Roquebillière, new Roquebillière, and St. Martin. The only son of Ettori and Maria Corniglion was lame; he was a schoolteacher at Lyons; during the holidays, which he spent at home, he spoke hardly a word, and read Dostoievsky and Julian Green. Their daughter was also a school-teacher; she was about thirty, rapidly becoming an old spinster, with a dark moustache which she shaved with a safety-razor. The fact that both the Corniglion children had become members of the corpsd’enseignement bore testimony to Mme. Corniglion’s ambitious character. She gave another proof of it when, the year before the landslide, she had fixed to their farmhouse gate a notice with the inscription, ‘HOTEL ST. SÉBASTIEN.’ Her third remarkable achievement was the purchase of the villa. But there old Ettori put a stop to her extravagance. He would not hear of repairing and refurnishing the villa. He planted the better part of the garden with various kinds of salads and vegetables, and installed a pig in the summer house. The villa itself was not touched and stood empty for another ten years. It was altogether thirty years since the proprietress had died, and the original rats and mice had been succeeded by the three hundred and sixtieth generation of their grandchildren, when we turned up.

There were three of us: Theodore, G., and myself. We had searched the Riviera during the past three weeks, from Marseilles to Menton and up the valleys of the Basses-Alpes and of the Alpes-Maritimes, for a suitable house to live in. Although our requirements were very modest, we had not yet found the house we wanted. We had, between us, ten pounds a month to spend. We wanted a house with a bathroom. G. is a sculptor; she wanted a room suitable as a studio, with windows which would fulfil certain conditions of light. She also wanted the house to be quiet, with no neighbours and no wireless within a radius of five hundred yards, as she intended to make all the noise herself with her hammer and chisels. I wanted to finish the writing of a novel, so the house had to be old, with thick, solid walls, which would stifle the sound of G.’s hammering; my room was to be furnished very simply and soberly, like a monk’s cell, yet with a certain touch of homely comfort. Then we wanted an abode for Theodore. Theodore was a Ford born in 1929, and with a noble pedigree of eight previous owners. The third owner had fitted him with a new body, and the fifth owner with a new engine. If it is true that the human body is completely renewed every seven years by the continuous discarding and replacing of the cells constituting its vital organs, Theodore was a new car. The only inconvenience with him was that we had always to carry two gallons of water in the dickey to quench his thirst, for he was unable to contain his water in the radiator—it escaped partly skywards in steam and froth and partly earthwards through sundry leaks. Hence the garage in the house which we were looking for had to have an easy access, which would spare Theodore those jerky leaps backward and forward which particularly annoyed him—after the third change of gear he would get a fit of megalomania, and blow white steam, believing himself to be a locomotive. Besides, the exit to the garage had to be on a slope to help start the engine, for Theodore’s only response to the starter-knob was a few chuckles and hiccoughs, as if the knob tickled him. We loved Theodore very much; he was still rather good-looking, especially in profile.

We arrived at the Hotel St. Sébastien one morning at about 2 a.m. Everything was very dark and very quiet. We sounded our horn for some time and Theodore roared into the night like a hungry lion, until finally Mme. Corniglion appeared. Our acquaintance started with a mutual misunderstanding: we took the St. Sébastien for a real hotel and Mme. Corniglion took us for rich summer tourists. But next morning, when she saw Theodore, a sudden cunning look came into her old peasant eyes. She sat down at our breakfast table and after some preliminary beating about the bush, and a furtive look round as if to make sure nobody was listening, she offered to let us a villa with a garden, a bathroom, a large barn as garage, a reception-room as a studio, a quiet little attic in which the gentleman could write his poetry, and all modern conveniences. Of course, she would need a few days to clean it and arrange it, as the house had stood empty for a few weeks, owing to the illness of an aunt in Périgueux. We had a look at the house and liked it at once. It was exactly what we had been looking for.

We agreed that we would move into the house in three days. We were to have our lunch and dinner at the Hotel St. Sébastien, breakfast would be brought by a maid who would come every morning to clean up for us. We were to pay 30 francs per head a day, or £5 a month, for villa, garden, meals, service and vinàdiscrétion—that is to say, as much wine as we liked or were able to stand.

We intended to stay three or four months, and work and drink vinàdiscrétion. We were very happy. We moved into the house in the beginning of August, 1939, about the time when the puppet Senate of Danzig decided its attachment to the Reich.

II

A company of shabby French soldiers was sitting in the sun on a wall covered with wild vine, dangling their legs. They rolled cigarettes and threw stones for a black mongrel dog. It was a funny little dog and they called it Daladier. ‘Vas-y,Daladier,’ they said, ‘dépêche-toi.‘Cours,monvieux,fautgagnertonbifteck.’ When we turned up in the car, they did not seem embarrassed. They made some joking remarks about Theodore, steaming and spitting as usual after the brisk ascent, and then went on urging Daladier to run and earn his daily bifteck. They spoke French to us and to the dog, but amongst themselves they spoke a kind of Italian, the special Italian patois of the region.

All the sleepy, age-old mountain villages of the Maritime Alps north of the Riviera were now packed with soldiers—grumbling, drinking red wine, playing belotte, and bored. We were on the road again, waiting for our house to be prepared for us; with poor Theodore, we climbed the tortuous by-roads indicated on the Michelin map by a dotted line with a green border—the dotted line meant ‘danger’ and the green border ‘picturesque view.’ There was Gorbio and St. Dalmas and St. Agnès and Valdeblore and Castellar—they all looked the same; eagle nests on bare rocks, carved out of the rocks, built of the products of the decaying rocks, stone, and clay. The houses, with stone walls as thick as medieval fortresses, were built on different levels, the ground floor of one row on a level with the upper floor of the row across the street, and some of the streets were actually tunnels, carrying enormous vaults, cool and dim in the blazing sunshine, like Arabian souks. But no one walked through these streets except a furtive cat, a herd of goats, or a very old woman in black, dry and twisted like the dead branches of an olive tree. When one climbed to the top of the village, one saw the neck-breaking serpentine road by which one had just come, and two thousand feet below, the valley; and far behind the decreasing mountains, the sea with Nice and the Cap d’Antibes and Monte Carlo, veiled by the mist. There lay the Shore of Vanity, and here was the realm of the Sleeping Beauty; but of an Italian Sleeping Beauty of the mountain, lying hidden behind a rock, bare-footed, with dry mud between her toes, with tangled, black gypsy hair straggling over her young and yet wrinkled face, and a goat’s-skin bottle of acid red wine warming on the hot rock within reach. Thus we had found St. Agnès and Gorbio and Castellar a year before; but now the soldiers had invaded the mountains, they had stretched barbed wire across the pasture and installed machine-guns and field-kitchens on the olive-treeterrasses. And they had woken the Sleeping Beauty by telling her that the French were going to fight the Italians because the Germans wanted a town in Poland. But, as she did not believe it, they offered her red wine and tickled her bare heels to pass the time.

We talked to many of the soldiers. They were sick of the war before it had started. They were peasants, and harvest time was approaching; they wanted to go home and did not care a bean for Danzig and the Corridor. The majority of them came from the Italian-speaking districts of the frontier region. They had become, in their habits of life, more French than they were consciously aware; they thought that Mussolini with his big gueule was a rather ridiculous figure and that all that Blackshirt business which began just beyond the next mountain ridge was a sort of comic opera. They rather liked La France, but they did not actually love her; they rather disliked Hitler for all the unrest he created, but they did not actually hate him. The only thing they really hated was the idea of war—and of any sort of political creed which might lead to war. And this was the point where these descendants of Italian emigrants had become most strikingly French: they had acquired very quickly the average Frenchman’s conviction that politics were a racket, that to become a Deputy or Minister was only a form of earning one’s bifteck and rather a fat one; that all political ideals and ‘isms’ were a matter of salesmanshipand that the only thing a sensible man could do was to follow the advice of Candide and cultivate one’s little garden.

Why, for what reason on earth, should they die for Danzig? The newspapers which they read—the Eclaireur du Sud-Est and Paris-Soir and PetitParisien—had explained to them during all these years that it was not worth while to sacrifice French lives for the sake of the Negus or for the sake of some Schuschnigg or some Negrin or Dr. Beneš. The newspapers had explained to them that only the warmongers of the Left wanted to precipitate France into such an abyss. They had explained to them that Democracy and Collective Security and the League of Nations were all beautiful ideas, but that anybody who wanted to stand up for these ideas was an enemy of France. And now the same newspapers all of a sudden wanted to convince them that their duty was to fight and die for things which only yesterday had not been worth fighting for; and they proved it with exactly the same arguments which only yesterday they had ridiculed and abused. Fortunately, the soldiers only read the crime and sporting pages. They had learned long ago that everything in the editorials was tripe and eyewash.

I wonder whether the French Command knew much about the morale of their troops. Perhaps they preferred not to investigate too closely, and thought things would be all right once the actual fighting started. I have lost my diary with everything else in France, but I remember writing in it on the day when the invasion of Poland began: ‘This war starts in the moral climate of 1917.’

There was only one consideration which prevented the average French soldier from looking at the war as complete madness and which gave him at least a vague notion of what it was about: it was summed up in the slogan, ‘Ilfautenfinir.’ His ideals had been gutted during the disastrous years of Bonnet-Laval-Flandin statesmanship; the cynicism of the Munich era had destroyed any creed worth fighting for; but he had been mobilised three times during the past few years and he was sick of having to leave his job and his family every six months and to be sent home again after a few weeks, feeling ridiculous and cheated. It was time ‘pourenfinir’—to put an end to it once and for all. ‘Ilfautenfinir’ was the only popular slogan, but it carried no real conviction. It was the grumbling of an utterly exasperated person rather than a programme for which to die. To fight a war only for the purpose of ending the danger of war is an absurdity—as if a person condemned to sit on a powder-barrel should blow himself up deliberately, out of sheer annoyance at not being allowed to smoke his pipe.

And on top of all this they did not, of course, believe that there really would be a war. It was just another bluff, and in due time there would be another Munich. The newspapers would again do a complete about-turn, and nicely explain that it was not worth while dying for Danzig. Marcel Déat had already done so in L’Œuvre. And so another lump of Europe’s bleeding flesh would be thrown to the monster to keep him quiet for six months—and another lump next spring and another next autumn. And, for all one knew, in due time the monster might die a natural death of indigestion.

So far France had not fared too badly by sacrificing her allies. ‘Toutestperdusaufl’honneur,’ a noble Frenchman had once said. Now he could say: ‘Nousn’avons rienperdusaufl’honneur.’

III

We moved into our house. It was a complete success.

At seven o’clock in the morning Teresa, the maidservant at the Hotel St. Sébastien, would bring us our breakfast. She was a dark and stolid young woman who worked sixteen hours a day for a salary of 50 francs, or 5s. 6d. a month. Sometimes Teresa was too busy, and then our breakfast would be brought by the Corniglion’s daughter, the schoolmistress, with freshly shaved upper-lip. After breakfast we went to watch Teresa feed the pig in the summer-house. The summer-house was so narrow that the pig could hardly turn round; just eat and digest and sleep. We had never seen such a fascinating disgusting pig. Then we walked knee-deep through the wet grass on the lawn and inspected our fig-tree. There were seventeen figs on the tree in different stages of ripeness, mostly on the topmost branches; we kept an eye on them and shot them down with stones when we judged them nearly ripe, before Mme. Corniglion, who also had her eye on them, had time to collect them. Then we worked until noon, and walked down to the hotel for lunch and vinàdiscrétion. Then came the siesta, and work again until the hour of the apéritif. Theodore was allowed a long rest and slept peacefully in his barn; his tyres were deflated and he looked shrunken, like very old people do; from time to time we would sound the claxon to see whether he were still alive.

We were very happy. All was quiet in the country of the Sleeping Beauty. True, those noisy garrisons had woken her, but she was still drowsily rubbing her eyes and yawning and stretching, and just put out her tongue at the growling monster. No, there would be no war. We would sacrifice another piece of our honneur—who cares for honneur, anyway?—and go on playing belotte. And writing novels and carving stones, and cultivating our garden, like sensible people should do during their short stay on this earth. Besides, Hitler couldn’t fight against the Soviets and the West simultaneously. And if the West made a firm stand this time, the Soviets would come in at once. There would be no war. You had only to repeat it sufficiently often, until you were sick of hearing yourself say it.

And all the time we knew that this was our last summer for a long time, and perhaps for ever.

By the middle of August green-and-yellow posters appeared on the town hall of Roquebillière, calling up the men of Categories 3 and 4 to join their regiments within forty-eight hours. Little groups of people collected in front of the posters, and the younger women appeared at the village shop with swollen eyes, and the older women, the widows of 1914, walked down the street in their black clothes with a gloomy and triumphant look.

Then the annual kermesse in honour of the local patron saint was cancelled. The dancing-floor was dismantled and the flagpoles pulled down.

And one Sunday morning a persistent cloud of dust hung in the air and a continuous confused noise of bleating and lowing and barking came down the hillside; the sheep and goats and cattle were returning from their pastures on the Italian frontier. The whole village gathered at the bridge to see them pass. It was a long procession, with tired, cursing shepherds, and sheep bleating incessantly, pushing and jostling each other in a general and senseless panic. The people at the bridge looked as if they were watching a funeral procession.

And yet there would be no war. We had to reassure, not only ourselves, but also the Corniglions and the village people who asked us our opinion, for, being foreigners and educated people, we must know. Our presence alone was a reassurance for them; if there had been a real danger of war, we would have gone home. Every morning, after bringing us our breakfast and feeding the pig, Teresa had to report to the butcher whether we really were still in the villa. We had become a sort of talisman for the people of Roquebillière.

The days passed. We tried to work. Telephone calls came from friends on the Riviera: they were leaving; everybody was leaving. We jeered at the paniquards. Last year at the time of Munich, G. had cut short her stay in Florence and I had cancelled a journey to Mexico at the last minute. This time we would not let ourselves be fooled.

There were still five or six guests at the Hotel St. Sébastien, who packed and unpacked their suitcases according to the latest news on the wireless: an asthmatic priest from Savoy, gloomy and congested-looking, who reminded one of those medieval mountain curés in the uncanny novels of Georges Bernanos. Then an Italian wine-merchant from Marseilles and a petty-officer’s widow from Toulon with three plain but coquettish daughters, the eldest liable to fits of hysterics. They all had their meals together at a long table in the dining-room; we preferred to eat on the terrace, even when it rained, to escape their company.

But we could not avoid the inmates of the asylum on the road below our villa. It was the regional asylum for the aged paupers, and for all cripples, village idiots, and harmless lunatics of the villages round about. It stood on the way from our villa to the hotel, and some of its inmates were always sitting in front of the institution on a wooden bench under a painted crucifix. There was Aunt Marie, knitting an invisible jumper with invisible wool; and the other old woman, wagging her shrunken head, not much larger than a grapefruit; and a third one, making faces and telling a funny story to which nobody listened; and a silent, always neatly dressed man with beautiful hands and a noseless death’s head. We had to pass them four times a day, on our way to the St. Sébastien and back, and they always stared at us in visible disgust. During daytime we tried not to notice; but we did not like walking past the asylum at night.

It was a strange place, Roquebillière. The houses destroyed by the landslide in 1926 had never been rebuilt and the débris had not been cleared away. Although the disaster had happened thirteen years before, half of the village consisted of the empty shells of abandoned houses and heaps of rubbish. They said there was no money to reconstruct it and to clear away the rubbish, but they had erected a large marble slab, like a war memorial, at the entry of the village, with all the names of the victims carved on it, mostly Corniglions.

They seemed to cherish the memory of la catastrophe. When we were still new to Roquebillière and heard the standard expression, ‘Il a péripendant lacatastrophe,’ uttered with a certain pride, we thought they meant the War of 1914. The inscription on the marble slab was composed in a tone of patriotic reproach. They felt that God had assumed a debt towards Roquebillière, and that he alone could be expected to do something about it.

In the year after the landslide, however, some of the younger men of Roquebillière embarked upon a truly extraordinary enterprise. They had heard of the rain of gold pouring down on the Riviera; and they wondered why the same thing should not happen in the valley of the Vésubie. They had received a fair sum from departmental and Government relief funds; so, instead of rebuilding Old Roquebillière, they decided to build a New Roquebillière a mile or so across the valley on the other side of the Vésubie, and to make it a fashionable holiday resort, a kind of Juan-les-Pins or Grasse. They found some estate agents to back them up and got to work. Two years later new signposts appeared all along the road from St. Martin du Var up the Valley:

TOURISTES!

VISITEZ LA NOUVELLE ROQUEBILLIÈRE, LA PERLE DE LA VÉSUBIE—à 4 Klm.

The Pearl of the Vésubie had about a hundred and fifty inhabitants, but accommodation for five hundred tourists. There were three hotels and an American bar, two fancy shops and another shop for souvenirs, and a town hall with an electric clock like a railway station. Everything was ready for the tourists, but the tourists did not come. They waited for them, first hopefully, then with growing despair, and finally they resigned themselves. Some of the pioneers went back to Old Roquebillière, the others just stayed on. Like ghosts in a deserted gold-digging town of Alaska, they shuffled through the asphalt streets, past the closed American bar and the closed fancy shops. They had as much use for the pretentious town they lived in as a miner’s wife for an evening dress; but it had swallowed up all their money and there was none left to tidy up the débris of their former home; so they put their last pennies together and erected the marble memorial as a double reproach to Fate.

It took us quite a time to discover that the main reason for the misfortunes of Roquebillière was its climate. The mornings were radiant, but at about four in the afternoon the sky over the valley would become grey and leaden. The atmospheric tension made us tired and irritable; once a week a crashing thunderstorm would clear the sky, but usually all the promising thunder and lightning ended in a miscarriage and the oppression remained.

Perhaps it was all the fault of the ogre—an enormous dark mountain on the other side of the valley, obstructing and dominating it and bending over it, as if to watch malevolently from above the clouds what was going on down below. The ogre had a strange outline; a large crack in the rock had thrown open its huge, man-eating mouth, with a single jagged tooth sticking out of the gaping lower jaw. We could escape the newspapers, switch off the wireless, and turn away our eyes when we passed the lunatics—but the ogre was always there, especially at night, watching us and watching the valley.

This Roquebillière had become a sinister, depressing place. Perhaps it had always been so, but now we saw it with different eyes. We knew it was our last summer, and everything around us assumed a dark, symbolical meaning. Yet it was still August, and the sun was still vigorous and bright and the figs went on ripening in our garden. We had never loved France as we loved it in those late August days; we had never been so achingly conscious of its sweetness and decay.

IV

I am definitely Continental: that is, I always feel the urge to underline a dramatic situation by a dramatic gesture. G. is definitely English: that is, she always feels the urge to suppress the original urge; and usually this second reflex precedes the first.

When, on August 23rd, I saw the inconspicuous Havas message on the third page of the Eclaireur duSud-Est, saying that a treaty of non-aggression had been signed between Germany and the Soviet Union, I began beating my temples with my fits. The paper had just arrived. I had opened it while we were walking down to the St. Sébastien for lunch. ‘What is the matter?’ said G. ‘This is the end, I said. ‘Stalin has joined Hitler.’ He would,’ said G., and that was all.

I tried to explain to her what it meant—to the world in general and to me and my friends in particular. What it meant to that better, optimistic half of humanity which was called the Left because it believed in social evolution and which, however opposed to the methods employed by Stalin and his disciples, still consciously or unconsciously believed that Russia was the only promising social experiment in this wretched century. I myself had been a Communist for seven years; I had paid dearly for it; I had left the Party in disgust just eighteen months ago. Some of my friends had done the same; some were still hesitating; many of them had been shot or imprisoned in Russia. We had realised that Stalinism had soiled and compromised the Socialist Utopia as the Medieval Church had soiled and compromised Christianity; that Trotsky, although more appealing as a person, was in his methods not better than his opponent; that the central evil of Bolshevism was its unconditional adaptation of the tenet that the End justifies the Means; that a well-meaning dictatorship of the Torquemada-Robespierre-Stalin ascendancy was even more disastrous in its effect than a naked tyranny of the Neronian type; that all the parties of the Left had outlived their time, and that one day a new movement was to emerge from the deluge, whose preachers would probably wear monks’ cowls and walk barefoot on the roads of a Europe in ruins. We had realised all this and had turned our backs on Russia, yet wherever we turned our eyes for comfort we found none; and so, in the back of our minds there remained a faint hope that perhaps and after all it was we who were in the wrong and that in the long run it was the Russians who were in the right. Our feelings towards Russia were rather like those of a man who has divorced a much-beloved wife; he hates her and yet it is a sort of consolation for him to know that she is still there, on the same planet, still young and alive.

But now she was dead. No death is so sad and final as the death of an illusion. The first moment after receiving a blow one does not suffer; but one knows already that soon the suffering will start. While I was reading that Havas notice, I was not depressed, only excited; but I knew that I would be depressed tomorrow and the day after tomorrow, and that this feeling of bitterness would not leave me for months and perhaps for years to come; and that millions of people, representing that more optimistic half of humanity, would perhaps never recover from this depression, although not consciously aware of its reason. Every period has its dominant religion and hope; only very rarely, in its darkest moments, has humanity been left without a specific faith to live and die for. A war was to be fought. They would fight, the men of the Left, but they would fight in bitterness and despair; for it is hard for men to fight if they only know what they are fighting against and not what they are fighting for.

This is what I tried to explain to G., who was born in the year of the Treaty of Versailles and could not understand why a man of thirty-five should make such a fuss at the funeral of his illusions—belonging, as she did, to a generation with none.

Next morning, August 24th, the news had spread from the third to the front page. We were spared none of the details. We read about von Ribbentrop’s lightning visit to Moscow and about his cordial reception—and I remembered what fun our Party papers had made of the ex-commercial traveller in champagne who had been promoted chief diplomatic salesman of Genuine Old Red Scare, bottled in Château Berchtesgaden. We learned all the picturesque details of how the swastika had been hoisted over the Moscow aerodrome and how the band of the revolutionary Army had played the Horst Wessel song—and I remembered the whispered explanations of the Party officials after the execution of Tukhachevsky and the other Red Army leaders. The official explanation (Version A, for the pious and simple-minded) stated that they were ordinary traitors; Version B (for the intelligentsia and for inside use) informed us that, although not exactly traitors, they had advocated a policy of understanding with the Nazis against the Western Democracies; so, of course, Stalin was right to shoot them. We learned of the monstrous paragraph 3 of the new treaty,1 a direct encouragement to Germany to attack Poland—and I wondered how this time the Party was to explain this latest achievement of Socialist statesmanship to the innocent masses. Next morning we knew it: Humanité, official organ of the French Communist Party, explained to us that the new treaty was a supreme effort of Stalin to prevent the threatening imperialist war. Oh, they had an explanation ready for every occasion, from the extension of capital punishment to the twelve-year-old to the abolition of the Soviet workers’ right to strike and to the one-party-election-system; they called it ‘revolutionary dialectics’ and reminded one of those conjurers on the stage who can produce an egg from every pocket of their frockcoats and even out of the harmless onlooker’s nose. They explained everything so well that, during a committee meeting, old Heinrich Mann, at one time a great ‘sympathiser,’ shouted to Dahlem, leader of the German Communists: ‘If you go on asking me to realise that this table here is a fishpond, then I am afraid my dialectical capacities are at an end.’

Poor old Heinrich Mann—and André Gide and Romain Rolland and Dos Passos and Bernard Shaw: I wondered how they would react to the news. How clever those conjurers had been to produce eggs out of the noses of the intellectual élite all over the world. And all the old workers of Citroën and the young workers in the dungeon of the Gestapo and the Members of the Left Book Club in Bournemouth and the dead in the mass-graves of Spain—we had all been taken in all right in the greatest farce the world had ever seen.

It was a bright, sunny day, this August 24th, 1939. I read the paper as usual while we were walking down to the St. Sébastien for lunch. I gesticulated and spoke very loudly. Aunt Marie, sitting in the sun and knitting busily her invisible jumper, gave us a shocked look as we passed the asylum.

V

There was an exhibition of Spanish paintings in the Musée National in Geneva. It consisted of the works from the Prado, which had been sent to Switzerland by the Spanish Government during the civil war. The exhibition was to be closed on August 31st; G. wanted to see it. I tried to persuade her that it was foolish to go abroad when the war might start from one day to another. But she said: Just because of that; it was perhaps her last chance to see the works of the Prado and nothing would prevent her doing it. So she left—on Friday, August 25th, exactly one week before the Germans invaded Poland. She was probably the only person in Europe at that time who went abroad to see the exhibition in Geneva.

I saw her to the cross-country bus for Nice, which was packed with panic-striken people evacuated from the frontier zone; I shoved her small suitcase on top of the heap of mattresses, frying-pans and canary cages on the roof; then the bus left.

It was five o’clock in the afternoon; I walked slowly back to our villa. So far G.’s presence had protected me from becoming fully conscious of what was going on. She had the post-Versailles generation’s typical way of taking for granted that this world was a hopeless mess; but this innate lack of illusions, instead of making her cynical, produced a sort of cheerful fatalism which made me, with my chronic political despair, feel like a sentimental, middle-aged Don Quixote. She had ridiculed me for drugging myself by buying all available newspapers and listening to all available stations on the wireless, and this fear of appearing ridiculous had a rather sedative effect. But now I was left alone and fell back into the grip of the drug.

On Saturday, August 26th, new posters appeared on the town hall: Categories 2, 6 and 7 were called up simultaneously. This meant practically general mobilisation; there was but one category of reservists left. I spent nearly the entire day in the Corniglions’ kitchen, where the wireless set was installed next to the large, old-fashioned kitchen range. The widow with the three daughters and the wine merchant and the asthmatic priest had all left the day before; the St. Sébastien had ceased to be an hotel and had become a farmhouse again. Teresa had taken off her shoes and stockings, and the wireless had returned to the kitchen. While Mme. Corniglion cooked on the kitchen range and old Ettori drank his pint of wine, I translated to them the news from Berlin and London; the odds for peace and war seemed now to change from hour to hour, and old Ettori said it reminded him of the way his grandmother used to cure chilblains by making him put his feet alternately in a bucket of cold and in a bucket of hot water. In the afternoon more evacuees came from the frontier, in packed cars, lorries and mule-carts; their luggage consisted mainly of mattresses and frying-pans, as if to demonstrate that humanity was going to be reduced to the mere satisfaction of her two primary needs. Late in the evening a telegram from G. came from Geneva, announcing her return for tomorrow, Sunday, night. I was relieved and had at the same time a feeling of mild I-told-you-so superiority: the telegram sounded neither fatalistic nor cheerful.

I had given up all efforts to force myself to work. Curiously enough, the novel which I was writing had its setting in Russia, more exactly in a Soviet prison;1 a few days before I had just finished a long dialogue, in the course of which the examining magistrate says:

‘We did not recoil from betraying our friends and compromising with our enemies, in order to preserve the Bastion. That was the task which history has given us, the representatives of the first victorious revolution.’

It was no concidence—just the hidden logic of events. Yet I wondered whether Cassandra felt any happier when the logic of events actually brought the Greeks to Troy.

So I spent most of the next day—Sunday, the 27th—in the Corniglions’ kitchen. Old Corniglion, too, for the first time since days immemorial, had not gone out to work in his fields; he sat next to the hearth, looking miserable and oddly out of place. I had become part of the family; we sat mostly in a mournful silence, a gathering of casualties of the guerredesnerfs.

After dinner I started up our weary Theodore to go and fetch G. from the railway station in Nice, I had plenty of time; the train was only due to arrive at about midnight; so I chose a secondary road over a mountain pass which we had always intended to explore. It was a moonlit night, the road utterly deserted and the villages I passed already asleep, with only an occasional window lit by an oil lamp inside. I stopped Theodore on the top of the pass and let the moonlight and the silence and the mountain air envelop us like a cool and soothing bath; and I remembered nights like this driving home to Malaga from the Andalusian front; and I wondered how soon we all would again curse the full moon and the stars, and pray for nights with fog and rain to hide the men of the earth from the men prowling between the clouds.

Eventually we descended on Nice about midnight. I had to wait for nearly an hour for the train, which was, of course, late—I think trains always rejoice in wars, which provide them with an excuse to shake off the wearisome fetters of the time-table and proceed at last at their leisure. There was an elderly Riviera-Englishman on the platform, waiting for his wife and children to arrive; after pacing up and down for half an hour past one another, we had a drink together at the buffet. He was as depressed as I, and confessed that, although for years he had been furious because we didn’t make a stand against the Axis, now that we were at last going to do it, he could hardly suppress a shameful wish to go on with the old, disastrous muddle. I know it is idiotic and criminal yet I almost want to say: For God’s sake give that bastard all he asks for—Danzig and Eupen and colonies and what not, and let us hear no more about him.’ I agreed that most of us were liable to the same sort of suicidal temptation:

‘It is the old story of going to the dentist to have a tooth extracted—at the moment of ringing the bell it stops aching, and one wonders whether it is worth while suffering the agony of the operation. Yet if we do not, the infection will gain the jaw, and eventually the whole body.’ I thought it was quite a good metaphor, but it did not sound convincing.

Eventually G. arrived, and on the way back we decided to stop pretending, and go home to Paris next day. She had travelled thirty-six hours to Geneva and back, and had only been able to spend two or three at the Exhibition—yet she didn’t regret the trouble and was quite content to have at least had a sight of the Prado treasures. For me in her place, the pleasure of seeing what I could see would have been poisoned by the regret of missing what I couldn’t.

VI

And so, after all, we too started packing.

It took us all the next day, and it was a melancholy business. G. had portrayed me in clay, and the life-sized head had to be stowed with much care and fuss in the depths of Theodore, and secured against the impact of the rest of the luggage. We eventually brought it safely to Paris with only one ear missing and the lips smeared together into a Mephistophelian grin—and it was grinning still when the Gestapo took it away in a removal van ten months later, together with my manuscripts, books and furniture, rugs and lamps included, from my Paris flat.

We dawdled over our packing, still hoping that some miracle might happen at the last minute, which would allow us to unpack again. How many people in Europe turned on the wireless on that Tuesday morning, August 29th, in the secret hope that overnight a benevolent stroke had killed the man whose disappearance would perhaps enable them to carry on with their mediocre and, in retrospect, oh, so pleasant existence! Instead, they were admonished in every language of the world to gird up their loins. They sighed, incredulous; they had lived so long under the sign of the Umbrella that they found it difficult to believe that the age of the Sword had come.

We finally left on Tuesday evening, when all pretexts to postpone our departure had been exhausted.

There were still three figs left on the tree in our garden. When we had manœuvred through the gate and turned our heads, the villa looked already as though no one had ever lived within its walls. We passed the asylum, but the bench under the crucifix was empty; Aunt Marie and the man with the death’s head had gone inside. We rolled over the bridge and waved to the Corniglions, but they did not see us; they were probably gathered for dinner in the kitchen, sitting by the hearth. The street was empty and none of the people of Roquebillière were there to wave us good-bye.

I stepped on the gas and we sped out of the village, feeling like deserters. While I write these lines, the Blackshirts are sitting in the garden of the Prince’s late mistress; they have probably killed the pig and picked the figs from the trees and put Teresa in the family way.

We passed the night in a deserted hotel in a deserted Nice; and all through the night we heard the plaintive neighing of horses which had been requisitioned for the Army and stood crowded together under the archways of the Casino Municipal. We had intended next day to push on our homeward way as far as Avignon; but early in the morning I went down to buy the Eclaireur du Sud-Est, and when I had finished reading the editorial I ran up the stairs like a madman to break to G. the news that there would be no war.

The Eclaireur was one of the important provincial newspapers of France; it was outspokenly sympathetic towards the de La Rocque and Doriot movements and supported the policy of Bonnet (who was still Minister of Foreign Affairs). In the previous weeks, during the dramatic crescendo of the European crisis, it had taken a line of uncompromising firmness towards Hitler’s Polish demands—according to the mots d’ordres from the Quai d’Orsay. In times of emergency, the Quai d’Orsay always exercised a kind of silently accepted dictatorship over the Press, which showed in such moments a considerable capacity for national discipline.

And now on this Wednesday, August 30th, when the German ultimatum to Poland was already on its way, the Eclaireur du Sud-Est