8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: BookRix

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

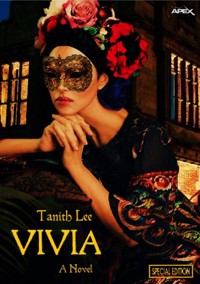

Vivia, a paragon of youth and beauty, daughter of Lord Vaddix, is alienated from his brutal campaign of violence and fear. Her only solace lies in the secret cave in the bowels of the castle, known only to her and the arcane god whose shrine she believes it is.

When plague enters the castle, bringing an orgy of death and destruction, Vivia seeks shelter in this seductive place. Drawn to her innocence and beauty, a presence - Zulgaris - is resurrected who claims her as his own. Wakened to the wonder of the undead, Vivia is granted the secret of eternal life, but she has been betrayed. Her immortality stretches before her like a damnation.

Handsome Zulgaris, dark prince, war-leader and alchemist. Is Vivia to be his lover, or his pet? Or, far worse, is she but one more thing to be used in this relentless quest for sorcerous power.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

TANITH LEE

Vivia

(Special Edition)

A Novel

Apex-Verlag

Index

The Book

The Author

BOOK ONE: Death and the Maiden

BOOK TWO: Queen of Night

BOOK THREE: The Powers of Littleness

BOOK FOUR: The Hag

The Book

Vivia, a paragon of youth and beauty, daughter of Lord Vaddix, is alienated from his brutal campaign of violence and fear. Her only solace lies in the secret cave in the bowels of the castle, known only to her and the arcane god whose shrine she believes it is.

When plague enters the castle, bringing an orgy of death and destruction, Vivia seeks shelter in this seductive place. Drawn to her innocence and beauty, a presence - Zulgaris - is resurrected who claims her as his own. Wakened to the wonder of the undead, Vivia is granted the secret of eternal life, but she has been betrayed. Her immortality stretches before her like a damnation.

Handsome Zulgaris, dark prince, war-leader and alchemist. Is Vivia to be his lover, or his pet? Or, far worse, is she but one more thing to be used in this relentless quest for sorcerous power.

The Author

Tanith Lee (* 19. September 1947, + 24. Mai 2015).

Tanith Lee was a British writer of science fiction, horror, and fantasy. She was the author of 77 novels, 14 collections, and almost 300 short stories. She also wrote four radio plays broadcast by the BBC and two scripts for the UK, science fiction, cult television series Blake's 7.

Before becoming a full time writer, Lee worked as a file clerk, an assistant librarian, a shop assistant, and a waitress.

Her first short story, Eustace, was published in 1968, and her first novel (for children) The Dragon Hoard was published in 1971.

Her career took off in 1975 with the acceptance by Daw Books USA of her adult fantasy epic The Birthgrave for publication as a mass-market paperback, and Lee has since maintained a prolific output in popular genre writing.

Lee twice won the World Fantasy Award: once in 1983 for best short fiction for The Gorgon and again in 1984 for best short fiction for Elle Est Trois (La Mort). She has been a Guest of Honour at numerous science fiction and fantasy conventions including the Boskone XVIII in Boston, USA in 1981, the 1984 World Fantasy Convention in Ottawa, Canada, and Orbital 2008 the British National Science Fiction convention (Eastercon) held in London, England in March 2008.

In 2009 she was awarded the prestigious title of Grand Master of Horror. Lee was the daughter of two ballroom dancers, Bernard and Hylda Lee. Despite a persistent rumor, she was not the daughter of the actor Bernard Lee who played M in the James Bond series of films of the 1960s.

Tanith Lee married author and artist John Kaiine in 1992.

Cover of the 1997 Warner-Books edition of DRINKING SAPPHIRE WINE

BOOK ONE:

Death and the Maiden

I.

Chapter One

Her father brought death into the castle. He carried carried it up the stairs. The pale horse.

The servants shrank back against the walls in terror. The armour of the man, the armour and hoofs of the horse scraped against the stonework. On the narrow upper stairways of the House Tower, for a moment it seemed they would be wedged fast, this incredible composite nightmare figure. The gigantic man clad in steel, and in his arms the dead stallion with its horned headpiece still on it, its eyes fixed like black balls. Vaddix was strong but the horse, his war charger, was huge. Yet he held it across his breast as he might have held his young bride.

The bride herself, Lillot, huddled staring in the hall below. She was frightened, foolish in her wedding regalia with its embroidery and ribbons, now made so unsuitable.

And it was to the bridal chamber that Vaddix climbed, staggering under the horse's weight. He kicked open the carved doors with a crash.

The room was large, filled by the great bed. Mounds of pillows and coverlets of yellowish lace, all strewn with the late wild summer roses, every one scaled of its thorns. On to this couch of love, Vaddix heaved off the stallion. It fell with a shock and the great bed groaned.

Then Vaddix roared his grief. He howled, and the horse lay there, darker and whiter than the lace, among the crushed red roses, and the chamber began to reek with the smell of flowers and sweat and blood.

Below, Lillot started to cry, and her women, trembling, tried to console her. 'There, there, little lily. He's won his battle. He's won you. It will be all right.'

On the wider stair, the first one Lord Vaddix had traversed, his black-haired daughter stood watching. She wore a gown of dark red, heavy golden earrings, bracelets, and a girdle of gold in the shape of daisies. Fluidly slender, not yet sixteen, she clasped her hands loosely together, frowning slightly. Her face was a white triangle, but unlike Lillot, Vivia seldom had any colour, except, as now, when she had reddened her mouth.

All her life she had known her father, not as anything intimate, but as a storm-like being coming and going, periodically overthrowing her life. This, now, was no exception. Massive, powerful, loud and selfish to the bone, he dominated the castle in his rage of dismay, just as he had always done in everything.

Lillot, the little fool, was not used to him, so she snivelled. Vivia's frown was one of contempt. Lillot was three years older than Vivia, fatter, sleeker, with a mass of blonde curls. A doll-like, trivial child of eighteen.

Vivia herself was a woman. Not only physically, as of course was Lillot, but psychosomatically.

Lillot did not raise her eyes to the black, pale and red hill of Vivia, in hope of any help. (There, there,' twittered on the stupid women.)

Lifting the gold-figured skirt of her gown, Vivia went up the wide stairs and into the gallery, as the raucous ranting howls of her father continued. She passed into the corridor that led to her apartment. She could hear too her own woman scurrying after her. Vivia closed the door in her face.

Ursabet beat on the door.

'Let me in, Vivia.'

Vivia put down the bar across the door, as if besieged. So she had been instructed to do if her father's battle had not been a success, and the enemy army, Lillot's kindred, had poured into the castle. But Vivia had not thought that this would happen.

Vaddix had stolen Lillot, after wooing her for about a month over an orchard wall, like a young man. Lillot, flattered and thoughtless, had not even resisted. Presently there was a feud, and Vaddix rode out and fought Lillot's kin, the Darejens, in the valley above the river.

The Darejens were levelled and sued for peace, but in the last instants of the fray, a cross-bow bolt had been fired directly at Vaddix, had missed him, and entered instead the brain of the white battle stallion, killing it immediately. After this Vaddix had massacred the last of the Darejens, and picking up the horse, alternately carried and dragged it up the rocky slope to the looming castle above.

Vivia crossed to her mirror, an oblong of impure glass mounted on a brazen lion. She looked in curiously. Like Vaddix, she was - or had had to become - self-absorbed. Each new event intrigued her, by its effect upon herself. Now she saw, apparently untouched, her stem-like form with its female breasts, her shining ebony hair, her beautiful cat's face that had narrowed its two dark, perhaps green, eyes.

Outside, the howls had stopped, and Ursabet had gone away. The castle hummed like a beehive, agitated.

From high windows, in the three grim towers of the castle, it would be possible to look out and glimpse the valley of the battle, where Vaddix, in his usual way, had crucified his foes in lines. The Darejens had been unwise.

Vivia wondered what Lillot saw in her father. Perhaps she was only scared of him. Obviously, she was weak-willed. If one of her tears was for her family, no one would know, perhaps not even Lillot herself . . . Something of an idiot.

The wedding now would probably be delayed. If he had truly flung the dead horse on the bridal bed, as the servants were whispering, doubtless they would not be sleeping there. Vaddix had already had the girl anyway, as he always had everything he wanted, at once.

The castle of Vaddix was like a fungus or vegetable, and its three towers stuck from its accumulations of stone like bony roots or stalks. Purple banners floated from the peaks. In a few windows, stained glass of raw rich colour showed pictures of the Christ, or heroic mythical scenes, giants and dragons and so forth.

The mountain flank which supported the castle was, in the last of summer, black, with a sparse fringing of pine and larch, and the land around rose up in enormous crags, or dropped into valleys of the river. This area of the river was, in spring, a carpet of greenness, bursting with flowers, but the summer water was lazy and brown with peat. The mountains themselves looked blank, merciless and obdurate, the farthest dipped in flat silver lines of snow.

Behind the castle of Vaddix was a walled garden, with walnut and cherry trees, wild pear, and the old statue of a pagan god with beard and the horns of a sheep.

The villages crouched below the height, property of the lord, about a thousand persons, who lived their days and nights in the shadow of the stone vegetable, gave it their service, were recruited for its fights and festivals.

To these places now the peasant army of Vaddix was returning.

Some were brought in dead, carried as the horse had been up to the castle. Some were hurt, maimed or only scratched. Vaddix's men from the castle, the knights of his household, had allowed wholesale pillage of what was left of the Darejen army, and in a handful of days, normally, bands would have set off across the valley pass to sack the Darejen castle in turn. This outcome was now unsure, for Lord Vaddix was in mourning for his stallion. And besides, he was a bridegroom.

The men and boys, as young as nine or ten, as old as fifty and bent nearly double, carrying rough swords, hoes, hammers, the bits and pieces habitually gathered for a war, came down the village streets. The women pressed out, looking for their particular men. News of the battle and the horse death went about. The women sun-circled or crossed themselves.

The priests, who had absolved them before their going, now came and welcomed them back, glancing at the wounded, seeing who might be saved and who was beyond saving. They packed down the eyes of the dead, the nearly dead. Life was cheap, souls emptied quickly like refuse on to the dump.

Dobromel the priest bent over the young man in the house door, who was refusing to go in or to recognize his wife, sister and sons.

'Where is he hurt?'

'No wound, father. Look, he's perfect.'

'I saw an eagle,' cried the young man, 'and it bore me up. But it tore me. Stop the pain, father.'

'Now, do you know me after all?'

'Yes,' said the young man. 'You're the dung-carrier.' He laughed wildly. Then gave a hoarse shriek. Blood oozed from beneath his left arm.

'You see, there is a wound. Take him inside. Bathe the cut with herbs and water.'

The women, used to obeying their priests, nodded. But one of the sons said, 'I saw him hacking at those Darejens. He said he had a pain there then. He had it all night since we waited for the enemy. It was in the meadow he got it. Perhaps something stung him.'

'Take him in,' said the priest. 'Look and see.'

Sunset. The sky red now as the blood of the Darejens, even the snow line red, and clouds banked like other mountains, equally obdurate and cruel.

Vivia had kept on her red dress, and as the sunset lit her white face, she crimsoned her mouth once more, at the lion mirror.

Her room was virginal and austere. A picture of Marius Christ painted on wood, his face hidden, as was usual, behind a mask of the sun. Roses in a pewter vase, slim as Vivia herself. The lean bed had curtains, and a lamp hung from the rafter. It was seldom lighted, thick with webs.

Ursabet, who had been allowed in at last, crouched over the chest.

'Wear this necklace.'

'No. It's too heavy.'

'He'll expect it. It's his wedding feast.'

'Perhaps he won't come to the wedding feast, and that fool will have to sit there on her own.'

'Nasty sharp tongue, said Ursabet. But secretly she liked Vivia's spiteful ways, she herself had inspired them. She had had charge of Vivia since Vivia's sixth year.

Vivia in any case did not deign to reply. Rather than put on fresh jewels, she had removed the bracelets, girdle, earrings and rings. Now only her dress was festive.

With Ursabet shuffling behind her, an elderly grey woman of forty-six, Vivia climbed the stairs of the castle to the upper hall, the banquet chamber, where the marriage and victory feast was to have been.

It was laid out even as the men fought in the valley - to have failed in this would have been unlucky. Now the room was filled by the lord's hungry knights, his ten warriors, who, starved, had not scrupled to begin. This was their right.

They stood about, in their armour still, plates and planks of metal, shirts of mail, in portions repaired or hung over by trophies taken in other battles, the gewgaws of men they had killed. They stuffed their mouths with bread, while the servants ran to bring them bowls of mutton hash, dishes of spicy rice, skewers of roast goat meat.

The chamber was red in colour, dressed with shields and weapons, and with painted rafters. Curtains of scarlet brocade hung down in places, and a tapestry so faded it was like a dead leaf picked out randomly in silver.

At the high table, draped with an embroidered whitish cloth, the bride, Lillot, was sitting in her finery, her eyes puffy and her round face pale.

Vivia in turn took her own place, at the upper table's end. A servant filled her pewter goblet with the rough mountain wine, and Vivia raised it, and poured out a drop on the floor, the old custom that even her father followed. She did not drink the wine herself; she did not like it, preferred water. She took a piece of bread, and crumbled some, putting a little in her mouth. Eating usually bored her, and she was not often hungry.

Besides, she knew - as surely the rest of them did, or they were all fools - that soon her father would erupt into the banquet hall.

He came with a clanging note, like a warning bell. He filled the doorway, and the lighted lamps shone on him.

The tallest man in the room, the villages, perhaps the world, his head, from which the helmet had now been removed, just missed the lintel of the door. He was broad, massive with muscle and hard big bone. For a moment he looked like a suit of armour that had come alive of itself, for like his men he had not stripped his battle gear. Only the head was human and that not very. Ugly, and scarred across forehead, cheeks and chin, the nose broken, pitted by some childhood pox, swarthy, with two beetle black eyes. Vaddix.

The thin gash of two lips opened to reveal strong teeth, broken only by war. He grinned at them, and one by one, his knights stopped chewing. They were afraid of him too. Only that had kept them, maybe, from banding together one night and hurling their lord off one of the three lurid towers. They hated and respected him, boasted of him, cursed him, challenged and cowered. Now, they bowed, and broke into a tardy shout. 'Lord Vaddix!'

'Yes,' he said, 'your lord. And here you are stuffing your filthy mouths with my food. You verminous dogs. Fuck the pack of you, you scum.'

One of the knights, Javul, said quickly, 'Didn't we earn our bones, my lord?'

'Yes, you fucking muck. You earned them. But what of me? What of my loss?'

The room was silent. In the lamps the wicks hissed on the oil, and on the dark beeswax candles, the flames flickered, steadied, as not a nerve twitched. Then Lillot the idiot began again to weep.

Vaddix bellowed at her: 'Shut your row, you bitch, you useless cunt. Shut your noise. It's your fault, you cunt, I lost him. My horse. The best horse on earth. For you I lost him. You. Are you worth it? I think not.'

Then he walked to the table and slammed into his position beside her, the sobbing, snuffling bride. The candles dipped and dived. Vaddix crashed his fist on the table. Things spilled.

'What one of you, you rabble, is worth my horse? This slut of the Darejens - no. Or that thing there,' he pointed at Vivia, remembering her as he occasionally did. 'What use is she? Worth only to be married to some enemy, and my enemies I slaughter.'

Vivia did nothing. She looked before her, unblinking, down at the floor of her father's hall. She was used to his tirades. He had never struck her, for she was always docile, and failing that, swift, running away from him if need be. He soon lost interest.

Vaddix roared for wine and the servant filled his cup, over-filled it, and Vaddix struck the servant instead, sending the man sprawling. Then, absently, Vaddix dropped a little wine to the ground, the pagan courtesy to ancient gods. He drank. Turning to Lillot he roared, 'Stop crying, you little bitch, before I make you.'

Lillot had stopped crying. She lay in a half faint in her chair, her women afraid to attend to her.

Vaddix's knights were seated. They had eaten their fill, and now they drank. The hall drank the people of the castle who sat down there. The vague relations, bastard lines engendered by Vaddix's own sire, or grandsire, their women. The fat priest Dobromel, who had arrived to celebrate the wedding and not been required to do so, who had hastily uttered a grace as Vaddix began to eat.

Vaddix had dined on copious amounts of meat, rice and pastry. He devoured these without words. The musicians who had come from the valleys to play lutar and harp and drum were redundant, sent out. No music tonight.

When he had eaten, Vaddix drank on, like the knights. He began to address the hall again. He was maudlin. Speaking of his horse, how it had carried him in fifty fights. How it had trampled and gored his foes with its metal horn.

Tears ran down Vaddix's scarred cheeks.

The silly girl did not attempt, not so silly after all, to comfort him.

'He'll lie there,' said Lord Vaddix, 'in that chamber. On my own bed. Where I was to have fucked her. He'll have that room until he rots. That's his.'

The heat pressed in at the narrow windows, one, its casement opened, showing in glass a winged hero who slew a bull.

The moon was not up, the night outside was black, but thick with the candles of blazing stars.

Tomorrow, left in the bridal room of the House Tower, the carcass would begin to stink. They would have to endure it. The whim of Vaddix was their law.

Vivia did not look at her father, or at anyone. She watched reflections of the candles, the falling heads of dying festal flowers. She had eaten a little rice and part of a tartlet with cherries, drunk water. She sat dreaming in her chair, thinking about incoherent glamorous things, stories Ursabet had told, still told her, which filled her sleep. This was how she kept tedium, the endless dangerous boredom of the castle, in check.

The coloured casement swung to a sudden night breeze. Red and emerald glinted on the hero's wings. What must it be to fly?

'Vivia,' said Vaddix.

She was alert at once. She said, not looking, mildly, brightly, 'Yes, father?'

'Did they tell you my horse was killed?'

'Yes, father.'

Vaddix said, 'Rather ten daughters dead than to lose him.'

Ursabet whispered behind Vivia's chair. It was a remedy for ill luck. Vaddix, fortunately, did not hear. He was deaf from his own shouting.

Some minutes later, Vaddix rose to his feet. 'Find a bed for that slut,' he said, of his unwed wife. 'I am going up the Spike Tower.'

His knights got up, in ramshackle unison, drunk and unready. He thrust them back with a gesture.

'What do I need you for, vermin? Who's left to harm me? I want to look out across the valleys. I want to see what's left of them, those Darejens.'

As he passed Vivia's chair, the hand of Vaddix caught a skein of her black tresses, squeezed it, let it go, showing how worthless was such stuff.

Black as her hair, the night out beyond the illuminated beacon of the castle. On the starry sky those towers, one with its eccentric quills, and a hole of light at its top.

Beyond the castle, down the slopes, the rocks, the sluggish gurgling summer river, with frogs in its water thickets and long fish under the stones.

The valley of the battle spread like a furrow, medallioned with boulders and bladed by pines, bent cedars and coarse chestnuts. To many of these trees were now affixed the fruited dead bodies of men. Vaddix crucified almost to a vertical, arms stretched up. Life did not often linger long, or if it did, in modified form. Limbs and blood, excrement and broken swords dangled off the trees, or lay in the pasture. In a stand of wild wheat other horses than that of Vaddix had perished.

The corpses lay, or hung, for about a mile, and with the vivid sunset ravens had circled from the mountains. Now they stood and perched upon the dead, picking and pulling busily.

Ravens, like bits of the night itself, feeding, sometimes uttering hoarse cries of appetite.

A feast for a feast . . .

Nothing to disturb the carnal scene, only the soft erratic passage of the night wind. And the white unlidded eye of the moon coming up from the east, between two crags.

From one of the villages a dog barked, starting off two or three more. Then silence. Only the rustle of the ravens, tugging and stepping, fluttering their night wings.

The young Darejen, fourteen years old, was breathing his last, with impossible difficulty, on the scarp of a chestnut tree. Above him the canopy closed out the sky, but one star had pierced through, vicious as a knife.

He had been thinking of the knife - the star - wondering if the knight who held it would come and finish him. He did not want to end, but yet he did. It was so desolate, this. And everything was over.

There had been terrible pain at first. Stunned, they had hauled him up, the two men, and then Vaddix's blacksmith had hammered in the iron nails, one at each wrist. The Darejen's hands were almost above his head, holding the complete weight of his body. He panted and choked, was constricted, and soon everything drew away from him, even the wish for life.

He had been fearful at first. For Vaddix would go now to the Darejen stronghold, and there he would work his violence again. Never before had Vaddix fought a battle so close to his own hold. Generally he laid siege. When once taken, the enemy house was destroyed. Vaddix had been known to crucify entire families, even children four or five years old.

The Darejen was afraid for his mother, but this fear finally also drew far away. Then he only hung there, not really breathing, waiting for nothingness, or for the Christ. Or for punishment, for he had often sinned - the girls of his castle, the prayers missed.

There had been sickness in the Darejen force - was this the anger of God? Had God brought them to destruction? Then what hope - ?

Dimly he tried now to remember Marius, the form of the Christ with blessing hands and his head of golden sun-mask and rays. Instead, the boy saw the dark valley before him, columns of trees hung with men, below, a fallen horse, everywhere, the ravens.

And then, the boy saw Death come walking down the valley.

It was - unmistakable.

The wind feathered over the grasses, murmured, eddied away. But this. This came straight and hard, pushing against the air itself. There was no shape to be seen, nothing but the passage of the thing. How the grasses bent away from it. And on the trees the scraps of armour tinkled, rattled and sang.

The ravens answered too. They flew straight up and out of its path. All but one. The creature - which was Death - came by the fallen horse, and the mane of the horse was ruffled - as if long fingers stroked it subtly. But the raven, feeding on the horse's belly, too greedy to fly away, sprang suddenly upwards. It spread its wings and its beak opened wide. Then it dropped back. It lay as if it had been crucified, wings wildly extended, beak gaping. Dead.

The boy on the tree hung and waited, and Death glided between the chestnut trees. And there, floating up in the darkness, two lamps were kindled, better than the star. The eyes of Death burned softly through, red as blood, yet cool, sombrous, and still.

The boy felt Death come to him, and fill him, his flesh and sinews and bones. Pass through him. He died almost instantly, like the raven.

Above the valley the moon drew clouds across her, hiding her face, not wanting to see.

Chapter Two

VIVIA LIFTED HER LIDS. HER eyes were definitely blue now, darker than the sky outside the window.

She looked about her slowly, carefully. The room was unchanged, but for two things. The roses had died in their vase, brown shrivelled heads, heavy, dismembered. And faintly, a rotten meat smell had entered. It was the stench of the decaying white horse above.

Prepared for both, Vivia sat up and threw off the thin summer cloth which had covered her nakedness.

She was white as a marble nymph, smooth as untouched cream. Beneath her arms and at the core of her, was long black fur, silky and cat-like. The rest nude as a pearl. The tiny pink nipples were like peony buds.

She shook back her hair. She stepped out of the bed. And from the corner where she slept, old Ursabet, like a grey rose-head, got to her feet.

‘There's your wine and honey, my love. Drink it up.'

Vivia rinsed her mouth with the sweet drink, swallowed a sip or two, and set the cup (dull iron) aside.

'The lily girl slept all alone,' muttered Ursabet. 'And he was in the Tower of Spikes.'

'What do I care?' said Vivia.

She did not care. The fool, Lillot, was nothing to her, her father less than nothing, unless he came awkwardly into view.

Ursabet poured water, and Vivia laved her body. Water pooled on the stone floor. The woman dressed her girl, perhaps marvelling over the loveliness of her youth. (Or perhaps not, for Ursabet had grown used to this, as she had to what time had done to her own body.) A shift and stockings gartered by ribbons, the outer gown of plain blue today, a blue not worthy of those eyes.

'What will she have to eat?'

'Bring me some fruit.'

Vivia pulled on her cloth shoes and raised the wooden comb to attend to her hair. She did not like Ursabet's combings.

Ursabet went out, and returned from the ante-chamber where food had been left, in the regular way. Brown bread, and peaches from the garden.

Vivia cut and ate half a peach.

She smelled the smell of the dead thing in the bridal chamber above.

Tell me about my mother,' Vivia said abruptly.

'Oh, Vivia. Well. She was a pretty girl. She would have been sixteen when you were born. She used to play with you.'

'And what happened?'

'She displeased him.'

'And he struck her.'

'Yes.'

Vivia put the uneaten half of the peach back on to the platter, and set the iron cup beside the rest.

'You shouldn't go there,' said Ursabet.

Vivia said, scornfully, 'You told me about it. Took me.'

'That was then. If he knew -’

'How will he know? He's drunk in the Spike Tower.'

'He'd kill me.'

Vivia said, 'Are you afraid to die?'

'Yes. I've been a bad woman.'

'Oh, you're afraid of that, said Vivia, pointing absently, as if at a younger child, at the holy picture on wood of Marius Christ.

Ursabet crossed herself. 'He's without sin. He judges us accordingly.'

Vivia laughed. 'Am I sinful?'

'Very. But death is far off from you.'

Vivia shrugged. She raised the platter of fruit, bread and wine. 'The castle stinks from his horse. I'm going down now. Down where he can't reach me.'

Ursabet shook her head.

Vivia paid no heed.

Down . . .

Through the stone castle, along its branching corridors, some narrow as a drain, others wide and hung with banners of the house of Vaddix, threadbare tapestry, old rusty axes, shields.

Down.

Past the warren where the servants of Lord Vaddix lived, the steaming kitchen with its hole of a hearth, and dead geese and onions hanging from the rafters. Down through the underchambers where stuff was stored and lost.

Past too the stench of open pipes, where the castle's bowel and bladder waste was extruded from the pile. Past ancient guard posts and secret funnels where rats chirruped.

Vivia was not afraid. She had come this way for almost ten years. Ursabet had brought her - You'll be safe here.

The under-part of the castle went into the rock of the mountain slope. Caves opened, natural pillars upheld half-made staircases. Then the way stopped at a terrible darkness, all the eyelets in the stone, which let in light, ended and over. No torch. No promise.

Here, in the black, cranky Ursabet had nursed the trembling child, Vivia. And later, Vivia, alone, seeking, had gone past the place, and found the other place. The inside of the rock, the underneath of the castle.

The caves were great and, unlike the dark just above, they shone. Phosphorescence lit them up.

Here natural steps descended. Waters trickled and in parts fell thick as plaits of white hair. Frogs trilled from the stony pools, frogs also white, as milk. And dark lizards, no larger than the palm of Vivia's then childish hand, fled over the rocky floor.

There were spiders with garnet eyes who floated in crystal webs dewed by moisture.

Other items had confused and intrigued the child.

For in the walls were coiled things, shells and ribs, and bones conceivably of the great dragons that once heroes had fought, so Ursabet said, on the land above.

The shells were especially beautiful. Caught in the rock walls, thin as lace. And from the roof of the underplace, long fangs of stone dripped down.

Vivia did not, six years of age, fear this region. No, it was a hidden spot that might, as Ursabet had stipulated, protect her.

Later she heard a frightened Ursabet calling, from the outer environs, and Vivia went back to Ursabet. 'Where have you been?' demanded the woman. Vivia told her, and Ursabet then had circled herself, and made another sign, older and more recondite.

Vivia had not been warned by this, nor by Ursabet's subsequent admonitions. The area under the castle was her safe place. No one else had dared it or would dare.

When she found there the carved snakes, coiled round and round, each with a smooth beaked head and adamant eyes, Vivia was about nine or ten. Then Ursabet admitted that the underplace was a grotto, an antique source of power and pagan virtue. To such gods as had inhabited or visited there, the lord of the castle and his people spilled their pre-feasting wine. To these, clandestinely, they made little superstitious signs.

The carved snakes had been offerings to the fount of the power that abided in the grotto.

At twelve years, Vivia began to carry to the grotto beneath the castle scraps of food and fruit, cups of liquor. It had been, nearly, a prissy moral act. The Christ she did not trust. The Christ was only a painting of a man without a face. But the formless thing - that might safeguard her, for once it had done so.

She was not religious, nor conscientious in her duties to this new shrine.

Sometimes strange dreams would commit her to it. Or the uncertain straits of adolescence. Or only pique at the boredoms of the castle.

Now it was the smell of death. The reek of the dead stallion.

Vivia passed into the cloaca of the rock.

It was always necessary to draw a breath before walking into the wall of darkness that seemed to have no exit. But this air was clean, smelling of damp medicinal fungus, water, and curiously dry stone.

Vivia took the breath.

This was the magic. Now she had absorbed the darkness, and might go on.

She glided, fluent and graceful, her hair blackly raying out, as exact a priestess as that lower region might desire.

She felt her own flawlessness, it was true. Had often done so. It helped, her physical arrogance, to drive out fear, for otherwise she might have been constantly afraid and so rendered impotent.

She went into the maw of the dark and was received, and journeyed about twenty steps. And then the rock curved and the glow of phosphorescence began.

It was wonderful, the way in which you could all at once see.

The enormous caverns and the bones trapped in their walls, if such they were, the grey-green mosses. Pools glimmering. The constant chorus of the frogs which did not falter at her approach.

Vivia, with her tray of offerings, walked straight forward.

By waters; fountains fell from above like needles. She crossed the paved stones.

She reached the curtain of white-speckled (leprous) ivy, and slid by.

She was in the central sanctum, better than the chapel of Marius in the castle, that smoky smelly hut in the courtyard.

Beyond the curtain the rock rose sheer, and in it bones had gathered like bees and serpents. They knitted together, elements of limbs and arms and wings that Vivia had never properly deciphered - consciously. And at their apex, maybe only some freak of form, meaning nothing, a masked, helmed face.

It was a face, of course, of bones. Itself like a vizor. The eyes were open portals, two ovals of dark. Nothing looked out of them. And the lips too, were closed.

Vivia dropped her offering, the peaches and bread, and poured the wine, at the foot of this sculpture.

Here she had laid thousands of such tokens, near where the snake stones had been set. The food and drink had rotted. Formed new material, a primeval slime, a fungus itself, that vegetated and so achieved fresh life. There was no scent of decay. Rather a clear homeopathic smell.

She bent towards it, then lifted her head to study the creature locked into the wall.

It was like a huge bat. A bat with the face of a man. Or even, of a woman.

But then too, it was like nothing at all.

Vivia sat back on her heels. She considered.

She had been six, and playing with her playful mother. She could recall nothing of this woman, not even the shade of her hair. Perhaps a hint of some warm perfume.

The door opened, and the storm and thunder of Vaddix were there.

Vivia sank away, but the woman only laughed to him, inviting him to understand.

Then Vaddix had shouted something at her, to get rid of the child, to get up, something.

And Vivia's mother had, winsomely, held out her hand.

It was then he came into the room and hit her very hard. So hard that, presumably, he had smashed her skull.

She fell back mute on the bed of hair whose colour Vivia did not remember, and Vaddix turned his black mad eyes to the child.

She did recollect the smell of drink, sweat, and unwashed angry male body, a dark smell, that reminded her now of nothing so much as the pall of the dead stallion.

Ursabet had seized Vivia, pushed her down.

'Say a prayer for the good Lord Vaddix,' Ursabet had squealed.

So Vivia joined her hands and prayed to Marius Christ, as every night until then Ursabet had made her do, for the health and joy of her father.

And he, he had folded away, gone out of the door. And then Ursabet took her, and running, bore her down under the castle.

Vivia glanced, sidelong, at the shape in the wall.

She did not ask for anything. (Her eyes - black now.)

She rose slowly, and going back through the ivy, she sat on the lip of a pool to watch the lizards and frogs darting in the water.

Chapter Three

UNDER THE WALL, THE GARDEN had pushed through. The arms of a walnut tree with hard

woody blobs on them. Bushes sprang out of crannies. The other opposing wall, of the Short Tower, made the place into a passageway.

Javul stood above a bush, pissing heavily into it.

As he did so, he heard a woman's voice in the garden above. Lillot. He knew how she sounded. Very young, and ripe.

He leaned into the walnut. There was the crack there in the stone which the tree had made, and through it he could see the greenery of the garden, and a piece of the old pagan statue, the sheep-horned man.

Lillot was wandering aimlessly about, pulling at flower heads from nerves.

Javul eyed her. She was nicely fat, big breasts and fleshy hips and a pulled-in waist, set off by a silver girdle Lord Vaddix had given her before the battle.

Noon sunlight smeared Lillot's fleece of gilded hair.

Javul's stream had ended. He ran his glance over Lillot and fingered himself, rubbing across the head of his cock. But then he packed himself back and laced up. After all, the way things tended now, he might get to have her.

He inspected quickly the wet earth under the bush. Here he had come by night and buried the golden Marius token he had ripped off the neck of a dead Darejen. A ruby had been set in where the sacred wound was, in Marius' side. The item was worth a bit. Now he came here and urinated

regularly, checking that none of the others had found the treasure; scent-marking.

Lillot's woman said something banal and cheering, something useless.

Javul grinned, and walked up between the walls and round to the garden door. He went in.

Lillot was startled. She clasped her plump white hands. The waiting woman, sensibly, drew back, going in under a cherry tree, pretending to look for fruit or something.

Javul went straight up to Lillot, tall and bulky in his leather clothes and broad belt knobbed by iron. He put out one big paw and took a handful of Lillot's large right breast. She stared at him with her mouth open. Javul felt her, then let her go.

'He's not treating you right, is he,' said Javul, kindly. Lillot made a small noise. 'Oh, you can speak up to me. I'm his man. His for life. But it isn't good, the way he's not married you and all. It should have been done.'

Lillot said, in a soft vague whine, 'He vowed it to me.'

'No doubt he meant it, too. Then. But he's quick to turn. The horse now. He won't get over it in a hurry. His father was the same. Killed a man for sneezing in the chapel.'

Lillot crossed herself. Her breast seemed to bulge and glow. She wriggled around it and he could hardly keep his eyes off it.

'He told me,' she said accusingly, 'the garden was mine. No one else would come in here.'

'Well, I came in to tell you, lady. I'm your man. I'll take care you don't come to harm. You need someone, now.'

He could see her thinking. She would have a little brain, not much room for thought, only the roots of her hair. Would she perceive the sense of what he said, or be too frightened? Vaddix was frightening. It was all very chancy.

'I expect,' she said, 'to be Lord Vaddix's wife.'

'Let's hope so.'

She looked at the ground. Her breast beamed at him, friendly.

The woman under the tree was scuttling about, rummaging, intent on not seeing a thing. The woman would probably advise Lillot that Javul was a lucky bet, if Vaddix failed.

Javul bowed, for they liked that, the girls. He said, 'Give me that flower. I'll keep it. It'll remind me of you.'

She handed him the torn bloom and he put it into his shirt.

As he swung off back through the garden, he could still feel her breast in his hand, and the flower tickled him lasciviously. He would perhaps only have to wait.

When the knight had gone, the woman came out of the tent of tree and began to arrange Lillot's garments, as if she had been seriously disarrayed. The smell of the man was all over Lillot, she might have been sprayed by a dog.

'I want to go home,' said Lillot suddenly. She was childish and the woman held her in scorn, not like Vivia the lord's daughter, of whom the servants were generally wary.

‘You can't do that. He's killed your father and brothers. You belong to Vaddix.'

'I must see the priest,' said Lillot. She had a religious inclination, hoping to persuade God, or the Christ, who were, after all, men.

They went out of the garden, and through walkways of the castle, down towards the chapel court. The sun cut in leaden gold between the deep shadows of high walls and louring towers. The Spike Tower reared like a porcupine, bizarre and intimidating. Up there he had spent his bridal night.

The rotting rancid smell of the dead horse hung in the air, adding an unseen brown colour.

There were always stinks, especially in summer, but this was a terrible thing.

The chapel lurked under the walls, four stone partitions and a roof of slates. There was one window of rose, yellow and white glass, showing Marius the Sun standing on the back of an ascending dove. This glowed at them strangely as they approached.

Lillot went into the chapel alone.

The aroma here was better, bitter herbs and rose-heads crushed on the floor, and incense in the golden censer hung from the beam.

Dobromel was sitting on his chair by the altar. He had been asleep, but, quick as a weasel, he heard the steps disturbing rushes on the floor. He feigned deep contemplation, and raised his skull slowly up, got to his feet.

'Do you wish to pray, lady?'

Lillot nodded.

She knelt down before the altar and put her hands innocently together.

What a baggage she was. In his youth, long ago, Dobromel had had one or two of her type, though none so opulent. It had been a sin, of course, but no one had ever found out, and even the girl who fell in the family way blamed it on the summer festival.

Now Dobromel had no leaning to sex. He found the idea of it remote and tiring, and so was able to be chaste.

Even so, there would be trouble with this hussy. If Vaddix did take her to wife, would she stay content? That round big bottom tightening her pastel gown, that crown of hair, were inflammatory material.

The castle was not safe, not reliable.

Dobromel would go back to his flock, the first village down the slope. After all, he was not needed for the wedding. And Vaddix was currently at his most insane.

Best to be away.

He watched the fat girl praying. She took a time over it, not he supposed from piety, but from trying to put sentences together.

Did God listen to her, or to anyone? Dobromel believed, not. God existed but was unreachable. It did not matter what you did. You must only be careful of men.

Lillot rose. She looked sulky.

She put a silver bead on the altar, and Dobromel evaluated it in silence.

'Will you speak a prayer for my dead kindred, father?'

'I will, of course, if you wish me to. Although, alas, they were our enemies, and yours too, once you joined yourself to the lord.'

Lillot looked unhappy. The ramifications of such honour did not make any sense to her.

She went away.

Dobromel moved into the chapel door, and observed the bright sunlight, and snuffed at the stink of death.

The girl had smelled of lust; even over the candles and the incense he had picked it up.

But here only the odour of the stallion persisted.

High in the blue sky a hawk was circling, or perhaps a raven, noting carrion.

Dobromel went back behind the altar and the screen, and took up his small bag of priestly things, adding the silver bead absently. There had been plenty of spoil from the fight, but Vaddix and the knights had given him nothing. He would do better with his villagers, who reckoned he intervened between them and the Christ.

He wondered, as he went over the courtyard and down between the bulks of the rocky, flinty, lumbering walls, if the young man with the blood coming from under his arm had recovered. If he had not, they might gift the priest with something fine, out of fright.

The shadow of the hawk went over Dobromel's face like a blade turning black.

They should have gone and buried or burned the bodies of the dead in the valley. (It was late in the year and already the red wolves might be stirring on the mountain flanks. It was not wise to tempt them down.) This too he must egg the men on to, in the village.

As he drew away from the castle, the stench faded. The heat then brought out the tinders and smokes of summer flowers, and next the normal reek of goats and sheep blown in from the pastures.

And then - then, even as the roofs of the village came in sight below, swimming in a haze of temperature, the vile smell began again.

Christ. What was this? Yes, the villages stank - of animals and humanity, of their middens. But not - this smell. This smell like Vaddix's dead horse.

Did he imagine it? Was it so thick still in his nostrils . . .

The priest stopped. He shot a look back at the castle, black on the burning sky.

He looked down again, at his village.

It seethed there, trembling in the haze, as if it were slowly cooking over some hellish underlying fire.

The usual sounds did not rise. Grindstone and lathe, forge, dogs, women chattering, men arguing. Instead a sort of murmur. Restive - like the crickets, feverishly rubbing in the bushes.

So, they were slothful, were they? That was not godly, and Dobromel knew his duty, for if they did not value God, Dobromel himself had no importance.

He must set them going again.

Was it five days he had been gone? Only that. Long enough, it seemed.

He strode towards the village, his robe and his fat swinging on his bones. His knotted girdle swung like a whip. He frowned.

And over the wooded meadows, he glimpsed the second village too, lying it seemed somnolent, like this one.

The bad smell got worse as he descended. It must be they had not attended properly to their chores. Perhaps some dogs had died, or sheep been slaughtered, and not correctly dealt with. Or, worse, men perished after the fight and not buried. No one had come to the castle to request Dobromel for any rite. He had assumed that, if there had been a death, they had called another priest from the adjacent villages.

Dobromel came into the main street.

The forge, he saw at once, was idle, no fire going, no one there.

Beyond, the door of the first house was fast shut.

He marched to it, and struck it.

A woman was screaming inside. He became aware of the sound as if it had been muffled and all at once the cloth was drawn away.

He knew the note. Not pain or a beating. They were fornicating in there.

A man grunted.

Dobromel glared, and smote the door open.

He said, loudly, into the gloom, 'This isn't the work for the day. Night things. What are you at?'

There was a sort of upheaval, and in the windowless murk he made them out, there on their straw bed by the wall.

They had performed it sinfully too, the dog or wolf position, the man taking the woman from behind. She was his wife at least, that much Dobromel beheld.

The stink was horrible. Death and sex all muddled, kneaded together, making something new.

But they were drunk, for there the beerskin was, lying by the hearth.

The woman laughed throatily. The man said, 'It's how we are, father. Since the battle. We earned it, didn't we?'

'No,' said Dobromel. 'You will come to me at my house tonight. I shall impose a penance.'

The woman collapsed under the man and he fell down on top of her. They were like some monster, changed abruptly into a legless snake.

Dobromel went out of the house.

A tiny child was sitting in the dust, playing with itself, with its genitals.

He shouted at it. The child slobbered and crawled away.

The air was so awful, stenchful, and thudding, like blood in the ears after a long run.

From another house came a woman's shrill cry, 'Get up on me! Wolf me! Wolf me!'

Dobromel walked straight down the street, ignoring the houses, until he came to the house of the man who had had the blood coming from him.

Dobromel rapped on the door. No one answered, and so he pushed it wide.

The house was empty. No one was there. There had been the man, his wife and sister, his old granny, and the two sons. None remained.

The interior looked as if something had gone on. Chairs overturned and broken pots, bedding across the floor, very stained. The smell was paramount here.

Dobromel backed out.

A man had appeared at another door. He beckoned. He said, 'My wife is sick, father. Will you come?'

'Sick in what way?'

'She vomits blood, father. And - there's something black, like a wart, under her arm and behind her knee.'

Dobromel said, 'Don't touch those places. Give her cool water to drink.'

'Where are you going?' said the man, bemusedly.

'I must return to the castle. Lord Vaddix demands it.'

A line from scripture came to him. And man shall fall upon woman, like unto beasts.

Dobromel hurried up the village street. He touched nothing that lay in the track, avoiding even the small shoe of a baby, and a cracked bone.

Within half an hour he had returned inside the castle. On a lower walk he met the strutting knight Javul.

'Plague?' said Javul, 'what are you saying?'

'What you've heard me say.'

Dobromel shivered. He was scalding hot with fear.

'But who's got it?'

'All of them, no doubt. Ill or sickening. The castle must be shut tight and nothing taken in from there. The other villages may be in the same condition.'

'Christ,' said Javul, 'may He fuck.'

He went away, and Dobromel sat down on the wall, shaking like an old man.

Thank God he had learned in time.

Even mad Vaddix was preferable - to that.

When the evening began to spread its blue wings, Vivia stirred.

She had been lying, dreaming, on her narrow bed for hours.

Earlier, she and Ursabet had played chess, but Ursabet was not a worthy opponent. Though cunning, she always let Vivia win.

Earlier too, Vivia had thought of going into the castle garden where, as a child, she had rambled about. But Lillot was there, and later a knight came into the garden also. Vivia hated the smell of men. Though she glimpsed, from an upper walk, the knight talking to Lillot, nothing of the conversation had struck her - she was too allergic to both participants to take in any detail.

The heat was awful in the afternoon, and the stink of death gathered, so Vivia laid across her face a wet scarf soaked in herbs.

The scarf had been her mother's, a floating amber thing sewn with golden swans.

Vivia felt no nostalgia at it. It was as if she were a child born from nothing, or from some odd combustion of heat and earth, water and air. She had no parents.

She had dreamed of flying, on blue wings, and seeing the dusk across the sky, its mottled petals, pierced her with a curious sweet hurt.

There was no one to tell of this. Ursabet was not there, and in any event inadequate.

Around her, the castle would be preparing for its nightly dinner.

Sometimes Vivia absented herself. This did not matter, she had no significance.

Tonight, unusually, she was hungry.

She wanted bread and wine.

She smoothed her dress and combed out her hair. One long black filament, a single hair, came loose, and she wound it round and round her finger. Now it was a black ring, a thing of powers -

From beyond the windows came a thin drear noise, one associated with the winter: wrong.

It was the howling of the red wolves.

She stole back to the window and peered out, as if to see their shapes gathering on the mountain sides.

Like threads of bronze, the voices coiled into the evening vault, where two or three stars had already been lighted.

Another star shone below. It was a murky reddish shade. In the village, they had lit a bonfire. Some celebration or calamity - those sounds, they did not come from above -

Ursabet crept in at the door.

'Oh, Vivia, Vivia.'

'What is it?' Vivia spoke icily. She was alarmed, for Ursabet, infallible sundial of the dreadful, had her croaking voice.

There's plague in the villages.'

In all Vivia's fifteen years, she had never known such a thing, but she had been told of it. Within her frame, a bell of steel seemed to sink, chiming dully, into her womb.

'They've closed the castle up. We must pray.'

Vivia said, with pure logic, 'Why?'

'It's God's punishment. We must entreat Him.'

Black winged, ravens flew across the blue wings of the darkening sky. Below, the weird fire, that must be of madness or cremation, deepened. Vivia did not contest Ursabet's statement. Vivia knew she would not pray.

Chapter Four

THE DAWN WAS LUMINOUSLY SCARLET.

Against a sky like a church window, flecked by golden notes of cloud, Vaddix's castle bulked like another, lesser, mountain. An ugly thing. And through its many-windowed towers, light ran straight by, like the shafts of spears and bolts.

The castle bled light.

Not a sound. Then the burnt cawing of ravens.

Vivia opened her eyes, and the blood light filled them, painted her face, the walls.

This was not a day like other days. Everything was changed.

A sudden terrible image - what was it? When her mother had been struck, and fell, a flying jewel, like a strange fly, astonishingly red - and it had touched Vivia's face. But Ursabet had wiped Vivia's cheek with her sleeve, before pushing her down to kneel.

'Ursabet,' Vivia said, sitting up.

Ursabet was on her pallet in the corner, looking old, and crumpled by the night.

'What is it?' Ursabet said, stupidly.

'Where's my wine?'

'Your wine? Yes, yes, I'll fetch it.'

Ursabet moved like an unwieldy piece of machinery. She had slept in her dress, which was rumpled, and patched darkly beneath the arms and between the breasts with sweat.

'You smell,' said Vivia.

'Do I? It's my age.' Ursabet cackled. 'Not young and sweet like Vivia.' In her eyes was a gleam of something equally cruel. Had Vivia ever seen it before - like a lean stoat looking from a hole.

Vivia drank all the wine. Last night the dinner had been rowdy and haphazard, the food scorched or half uncooked. The knights were extra loud, as if to stave off their fear. They had waited to hear the priest speak the full grace before they ate, and each tipped his cup, making the ancient offering, to which the priest turned a blind eye.

Vaddix sat at the central table, and by now Lillot had removed herself from his side. He said nothing, only ate and downed cup after cup. His mad face was unreadable. What was he thinking? What would he do? He did nothing.

They said he slept now in the bridal room, at the foot of the bed with the dead horse on it.

The awful bloody colour of the sky was reluctantly fading, and Vivia went to her window. There was no sign this morning from the stricken village. But the ravens wheeled overhead, perhaps a hundred of them, very black.

The castle was safe. Of course it was. Nothing could get in. No enemy. No sickness.

And she - Vivia - she stretched her white arms and felt her silken hair slide on her back. She was invulnerable with her youth, her sweetness, as she had always been. How else had she escaped her father? How else had she lived her life of boredom and alarms and arrogance.

It seemed to her the stink of the dead horse was not so appalling or so strong. Gradually it would evaporate leaving a clean heap of bones. The summer heat would pass and snow creep down the mountains. The cold would cauterize the plague. Everything would be all right.

Javul had woken bulging, but not masturbated. Self-abuse was a sin worse than fornication. But it was not this which stopped him, more the anticipation of what he would soon have instead. He could imagine squeezing that big white velvet bum, like a peach, and pushing in and in. He rose

and pulled on his garments, drank the beer that had been left him, and went to seek his breakfast in the dining hall.

She was there, with the two waiting women, and they, noting him, moved off.

Javul sat down beside Lillot.