Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Frauenzimmer

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: The Life of Duchess Elisabeth of Saxony

- Sprache: Englisch

In 1526, when the mere possession of Luther's works was a punishable offence in Dresden, young Duchess Elisabeth professes her support of the Reformation ever more openly, thereby making bitter enemies for herself at the court of her staunchly Catholic father-in-law George, Duke of Saxony. In innumerable letters, Elisabeth tries to keep the peace between her father-in-law and her Protestant brother, Landgrave Philip of Hesse. This is construed as espionage and costs her Duke George's favour. When Elisabeth's adversaries then accuse her of marital infidelity, she falls completely into disgrace and Duke George even threatens to have her walled up alive ... This novel is a plea for religious tolerance, which is as important today as it has ever been. The author describes the eventful life of a woman who lived on a razor-edge in a time full of contradictions and dangers, without losing sight of the larger context of European history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 830

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Anja Zimmer

Wisdom In Our Hearts

The life of Duchess Elisabeth of Saxony

Novel

© Anja Zimmer, Frauenzimmer Verlag, Laubach - Lauter, 2011.

All rights reserved.Reprint and reproduction of any kind, use in other media and languages,electronic storage, editing or treatment – including excerpts – onlypermitted with the consent of the author.

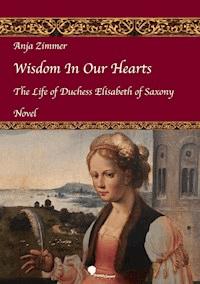

Cover illustration by a member of Joos van Cleve‘s circle,right wing of triptych showing St. Barbara© LVR – Landesmuseum Bonnwith the kind permission of the LVR – Landesmuseum Bonn.

Cover design, composition and layout: Anja Zimmer

Translated by Jigme Chödzin Balasidis

Ebook ISBN: 978-3-937013-23-7PDF ISBN: 978-3-937013-22-0

WWW.FRAUENZIMMER-VERLAG.DE

Note: On the website of Frauenzimmer Verlag there are pictures of the locations mentioned, as well as further information for research and background.

For Frank,

the best husband in the whole universe.

Contents

Wisdom In Our Hearts

Bibliography

Index of Persons

Meissen, May 1526

“Your Grace! Your Grace!”

The person thus addressed – George, Duke of Saxony – once again suspected trouble approaching. There could be no doubt, the chief lady-in-waiting was indignant. Indignant was hardly the right word. She was obviously furious in the extreme.

The court had betaken itself from Dresden to this lovely castle with its spacious garden to enjoy the blossoming of May. The sun was shining, the scent of flowers and fruit trees was everywhere, yet the idyllic scene was now harshly disturbed by the hofmeisterin, who came down the garden path with garments rustling. A closer look showed that she was even kicking up a small cloud of dust. She must be entirely outside herself, for this woman, charged by the duke with the care of his daughter-in-law, would not otherwise have cast all decorum to the wind and called out to him from such a distance.

What could Elisabeth have got up to now? Duke George was curious whether this hofmeisterin was also about to ask him to remove the heavy burden he had placed on her shoulders in the form of his small, willowy daughter-in-law. At some point he had already ceased to count how many hofmeisterins Elisabeth had already worn out. Elisabeth was unusual. In many respects. She was extraordinarily intelligent, self-assured, strong and free. Her brother Philipp had taught her things one would not expect of a well-bred girl. Elisabeth could skip stones over water, which in itself was rather harmless. But she could also scare the wits out of her ladies-in-waiting by giving a shrill whistle through her fingers. Furthermore, she must have had other teachers beside her brother, for she occasionally came out with the most indelicate sayings, which she then declared to be “ancient Hessian words of wisdom”. As if that were not enough, she could also swear as if she were leading three armies, as one of her hofmeisterins had put it.

Such were the thoughts occupying the duke’s mind as he saw the chief lady-in-waiting hurrying towards him.

“Your Grace!” she called once again.

Duke George turned to his two councillors and dismissed them with a nod. Hans von Schönberg and Heinrich von Schleinitz obediently stepped back, but were careful to stand close enough to hear each word declaimed by the esteemed hofmeisterin, who now stood, out of breath, in the presence of the duke.

“Yes, Lady …”

“Köstritz. Countess Eleonore von Köstritz, if it please your Grace.”

“Yes, yes, we are quite pleased. Arise!” he demanded impatiently of the no longer youthful lady who had fallen into a deep curtsy before him. Since Duke George was obliged to fear that she would be unable to stand up on her own, he proffered his hand, which she gratefully accepted.

“Well now, my dear Lady Köstritz, your matter seems to be of the utmost urgency.”

“It is, indeed, your Grace. Your Grace was recently so kind as to appoint me to be hofmeisterin to your daughter-in-law. For which I am also very grateful to your Grace …”

“We are very glad, Countess. Then all is in order. We had feared you were not satisfied with the duty entrusted you.”

Duke George was now looking into a face which, within a very short time, was taking on the most diverse shades of expression. Lady Köstritz’ countenance revealed a struggle between the most humble respect, despair, hope of mercy and a clear will to survive. When it came to Elisabeth, it was apparently a matter of life and death for the poor woman.

“Your Grace is too kind,” Lady Köstritz was finally able to stammer, “yet I am afraid that I am no longer up to the task appointed me.” She looked almost relieved to have been able to let these words to the duke pass her lips. Messrs. Schönberg and Schleinitz nodded to each other fervently. This was more good news.

“No longer? But you have only been hofmeisterin for three months,” said the duke, feigning surprise.

“May your Grace pardon me, it has been exactly two months, three weeks and five days. The young Duchess is too much for me. Just now she put me in a situation … a situation!” Appalled, the Countess put her hand to her forehead and sighed.

Fortunately, she had closed her eyes to do so and thus failed to see the duke’s eyebrows draw up menacingly.

“What sort of situation?” asked the duke, who did not at all like to be addressed in any manner other than clear and concise. The countess, who immediately realised that she would have to control herself if she did not want to annoy the duke, now stood staunchly erect in front of her lord.

“May your Grace forgive me, but I cannot by any stretch of the imagination say this thing to your Grace.”

“We shall be neither merciful nor gracious, nor forgive you, if you do not instantly tell us what happened.” The duke’s patience was at an end.

Schleinitz and Schönberg, leaning forward to soak in every word, hardly dared to breathe.

Now Countess Köstritz hesitatingly reported how she had been walking through the garden with Elisabeth. Once again, she had made a futile attempt to teach her how to take elegant steps. Elisabeth merely replied that she was not a horse to be taught its paces and took the stairs two at a time out of spite. Then, however, they strolled through the back portion of the garden, where one of the gardeners was standing engaged in … well in something entirely unspeakable. The horrified countess begged Elisabeth to turn away and wanted to take another path just to get away from this shameless man. But Elisabeth called out to him a rhyme which … no, no, out of the question, Countess Köstritz simply could not let such words escape her lips.

Duke George concluded that one of the gardeners, thinking himself unobserved, had been passing water and Elisabeth had once more brought forth one of her Hessian words of wisdom.

The duke sighed. He had known Elisabeth’s mother Anna and father Wilhelm well. He had stood with Elisabeth, her brother Philipp and Anna at Wilhelm’s deathbed and consoled Anna. He had helped Anna when the Hessian Estates refused to honour Wilhelm’s testament and had even wanted to take her son away from her. Anna had been a strong woman, beautiful and intelligent. Much of this she had passed on to her daughter. But Elisabeth’s childhood and youth had been marked by her mother’s battle for her son and the right to rule. As well as deprivations, for the regents and guardians had refused to furnish Anna and Elisabeth according to their station. Anna had often been away at meetings of the imperial and state diets. Elisabeth grew up with her foster mother in Marburg, Spangenberg and Felsberg, where manners were obviously anything but princely. To be sure, that is where she will have learned all those things which were held against her at the Dresden court.

Mother and daughter had always been very close. It was just one year ago that Anna had died. Elisabeth was not yet over her mother’s death. Even though she put on a cheerful face in company, Duke George knew that the death of her mother was but one sorrow among many.

The duke took a deep breath and looked at the countess, who quickly lowered her eyes.

“Very well, Lady Köstritz, you may go. You are henceforth relieved of your duties.”

The countess bowed low and hurried away.

Duke George turned to his two councillors. They quickly stopped leaning forward and stood erect, whilst Schleinitz hastily moved his hand from behind his ear to behind his back. Both attempted to look as disinterested as possible.

“We would like to speak with Duchess Elisabeth.” Duke George told them, “- Or no, wait! Duke Hans! Bring us Duke Hans! We will await him in that arbour there.”

The two bowed without a word and disappeared. Schleinitz deliberately began searching for the young duke, while Schönberg followed on the heels of the good Lady Countess with a joyful spring in his step in hopes of discovering what Elisabeth had said.

The duke let his gaze sweep across the garden. He saw scattered nobles in their colourful garments walking about the garden, some deep in conversation, others pointing out especially lovely blossoms or even bending down to pick a flower. Duke George went slowly over to the arbour which his wife Barbara particularly loved. She always very much enjoyed the few hours he was able to spend with her. He had also frequently sat here and talked with Elisabeth. She was good to talk to, a rarity among the younger women.

It did not take long before Duke Johann appeared. It had cost him some effort to find the arbour in the garden by himself. He hurried up, and when he was close enough to discern his father’s expression, he quickened his pace even more until, rather out of breath, he was standing in the arbour where his father was seated upon a bench.

“My Lord Father, you had me summoned.” Johann gave a low bow.

“Yes, Hans.” The duke said nothing more, but turned away without giving his son permission to sit down. Johann became somewhat agitated and began to shift his weight from one foot to the other. He could imagine why his father wanted to speak to him. He found the duke’s silence increasingly unpleasant. He did not want to look even indirectly at his father’s face, so he began to study the paintings decorating the inside of the arbour. Somewhere a cricket was chirping.

“Your spouse’s hofmeisterin was with us a moment ago.” Johann took a deep breath, but before he could respond, his father continued. “She literally begged us to release her from her duties.”

“I’m very sorry, Father,” Johann said softly and looked up at his father, even though he was standing and his father was seated. Johann often wondered how his father always managed to make people look up at him no matter what their relative positions might be. Johann felt his heart beat faster.

“Elisabeth gave forth one of her bits of old Hessian wisdom. The hofmeisterin strictly refused to repeat her words.”

Johann said nothing, looking self-consciously at his shoes. He was a man nearly twenty-eight years old and had been married for ten years, yet his father persisted in calling him Hans, as if he were still in kindergarten, and he still trembled whenever his father scolded him.

“I will speak with her,” he finally managed to say, hoping it would get his father to let him go.

“That is what you have been telling us for the past eight years1, each time Elisabeth put another hofmeisterin to flight. It will not suffice merely to speak with her. You must make some progress with her. Something has to happen. It cannot go on like this.”

Johann’s trembling worsened. His parents had chosen Elisabeth for him. At the time, he had acquiesced in the long agreed marriage. Now this woman was giving him nothing but trouble and he was standing in the dock, just as if he had chosen her himself. Once again Johann felt resentment welling up inside him. But instead of defending himself, he said nothing. To his relief, his father himself now realised that Johann bore the least of the blame for this union, for the duke said, “There is this family pact with Hesse, you know. There simply have to be marriages. Perhaps we should have had Elisabeth brought to ourselves and raised her here.” After brief consideration, however, he added, “But her mother would never have agreed to that. We know that she also has her good sides. Yes, she is, after all, a good woman. We enjoy talking with her. She is intelligent. She asks questions that most would find challenging. We thoroughly enjoy her conversation. And even to us she speaks without the least inhibition, as if we were an old acquaintance and not the Duke of Saxony.” While speaking, he stroked his constantly well-groomed beard, as he always did when he was slightly annoyed. This now made Duke Johann uneasy. “I beg your Grace not to interpret this as lack of respect. She speaks in precisely the same way with God,” he said, and when his father lifted his brow questioningly, he added, “She always says her prayers aloud. And she is just as outspoken and uninhibited when speaking to God as she is with you.”

“So! Your wife is on a familiar footing with the almighty creator of heaven and earth as well. I suppose we should feel flattered!” the duke observed.

Johann, far from remarking his father’s witticism, lifted his shoulders in assent and showed a serious face. The danger of taking as a joke something not so intended was simply too great. And if one laughed, the consequences could be anything but amusing.

“God!” the old duke muttered and then said aloud, “But why does God not hear her prayers? Or does she not pray for a son with sufficient ardour?”

Johann remained silent, now closely watching a beetle taking a stroll next to his shoe. The beetle had long feelers and an iridescent green body.

“Do you make sufficient effort?” His father’s voice sounded sharp.

“Yes, father, we do,” answered the harrowed Johann. In the meantime, the beetle had climbed up one of his shoes. Fashionable cow-mouth shoes with slits. Now the beetle was heading straight for these slits.

“I beg your Grace to believe me that there is nothing we more fervently desire.” The feelers, followed by the iridescent body, had just disappeared into one of the slits.

“You may go, Hans.” Johann did not need to be told twice. After bowing assiduously, he hurriedly took his leave.

The duke looked after his son who – for whatever reason – was strangely jiggling his left leg, and sighed. On the whole, Duke George held his daughter-in-law in high esteem. She was decidedly close to the people and the Saxons liked her very much. She was a pretty young woman, twenty-four years old, almost as beautiful as her mother Anna. Her mother-in-law and the other ladies at court were less fond of Elisabeth, however. This may have been due to her youth and beauty, or her intelligence, in which she far surpassed most women at court and which she occasionally used to get revenge for the constant innuendos regarding her failure to bear children. Perhaps it was because she was the only one at court who confronted him, the duke, without inhibition. Probably it was a combination of all of these.

However, it was feared that Elisabeth had been infected with the Martinian2 disease while staying with her brother. Philipp of Hesse already openly confessed to being a follower of Martin Luther. This was the reason Duke George took care to keep the siblings from meeting, for as soon as they saw each other again, Philipp was sure to convert his sister entirely to this new, blasphemous doctrine and thus put the salvation of her soul in danger. Young people seemed simply unable to refrain from recklessness in this matter! They did not bear in mind that they would one day die and have to justify themselves to God. Then it would be too late to acknowledge the true doctrine and spend eternity in heavenly peace. Impossible to imagine what would happen if Elisabeth in turn started to spread this dangerous nonsense at court in Dresden. But it must not come to that. He would see to it.

Duke George saw the tall, scrawny form of Herr von Schleinitz hurrying towards him through the garden. The latter remained standing at a respectful distance and made a servile bow while offering a tray with a letter on it to the duke. The duke waved him nearer and took the letter.

“You may withdraw.” Noticeably disappointed, Herr von Schleinitz took his leave.

The duke looked at the seal. It was the seal of Electoral Prince Johann Friedrich, cousin to his daughter-in-law. He quickly broke the seal and removed the strip of parchment holding the letter closed. The contents of the letter were such that the duke himself set off to search for the lady Elisabeth.

He heard her laughing in the distance. That was Elisabeth. It came from the sheltered spot where the ladies of the court liked to sit together. When the duke came within hearing, he paused.

“What do you think?” one of the ladies called out indignantly. “The Turk has been at the gates for years. This is a serious matter. One does not joke about such a thing!”

“Oh! The Turk?” This was obviously Elisabeth speaking. Yet there was more than mere amusement in her voice. It would have to be called blatant derision. “Are you referring to a lone Turk who single-handedly populates the huge Ottoman Empire? And he is standing there all by himself? For years? The man is persistent!”

“Do not mock, your Grace! Such things do not concern us ladies in the least. These are matters for men.”

“She would do better to see that she gives birth to a son and heir!” one of the others hissed, loud enough that all could hear, which resulted in more or less unconcealed laughter.

Duke George gnashed his teeth.

“But of course! Simply be patient!” Elisabeth chirruped.

“Maybe we should let the Turk in. A man with such stamina might even be able to help your Grace get with child!” taunted another.

“Or teach you to read and write,” Elisabeth countered, and brought her entire verbal artillery into position within a matter of seconds. However, Duke George decided to intervene before she was able to fire off any more rounds. He stepped forth and the first lady who saw him rose from her seat with a surprised “Oh!”, hastily falling into a deep curtsy. All the others hastened to follow her example, then remained immobile. Only Elisabeth quickly stood and approached her father-in-law.

“I wish you good day, my Lord Father.”

“We thank you, Elisabeth. We would like to speak with you.” And turning to the ladies, he said, “You may rise.”

Elisabeth had immediately noticed the letter in the hand of her father-in-law. “I hope you have good news for me,” she said, and took his arm, which met with horrified shakes of the head from the other ladies, who had now risen from their awkward postures and were watching them go.

“It depends how one looks at it. First, however, we must ask you some questions. Lady Köstritz was with us just now. She refuses to carry on as your hofmeisterin.” He heard Elisabeth exhale loudly.

“What was it you said to the gardener? - But no, we would rather not know,” he quickly added, with a deprecating wave of his hand. He recalled that the hofmeisterin had complained of Elisabeth’s way of walking. Indeed, his daughter-in-law walked briskly next to him, her steps keeping pace with his own. It was pleasant to walk with her. Not so with his wife, whose tiny steps could not keep up with his own gait.

“Elisabeth! This cannot go on. You must at some point defer to a hofmeisterin and accept that you still have things to learn from her.”

“I am learning. Truly, I am. I am learning quite a lot. However, I prefer to learn by reading. Speaking of which, do you not have a letter for me?” The duke gazed at his daughter-in-law, who smiled up at him and her blue eyes looked so friendly that it cost him a great deal of effort to remain cool.

“You missed early mass again today. Your husband has assured me that you are very pious. But your infrequent presence at early mass would seem to give the lie to his words.”

“No, no, my Lord. I lie awake so often at night and cannot go to sleep. Not until the early morning hours, when the sky begins to lighten, can I finally fall asleep. Then, of course, I have to make up for the sleep I missed during the night. And sleeping in my own bed is much more refreshing than sleeping on a hard church pew.”

“Elisabeth!” Duke George replied, in a tone that was sharper than Elisabeth was accustomed to hearing from him.

“Forgive me, lord father. I did not intend to be unseemly. My health is not of the best.” She then kept still.

“Enough of this. We will speak no more of it. – I have something which may improve your mood.”

“You mean the letter. Do you have good news? Is my brother finally going to visit us?”

“Not your brother, but someone you like so well that you might also call him brother, and one who comes directly from your brother Philipp. Read it yourself. Although the letter is not addressed to you, you may read it nonetheless.”

“Thank you, my Lord. That is very kind of you!” She took the letter, unfolded it and skimmed over the lines.

“This is delightful news! In a few days the electoral prince will be here. But we shall receive him in Dresden, shall we not?”

“Certainly. We shall return to the castle forthwith tomorrow to make preparations. We only hope he does not arrive before us.”

“Shall we hold a feast in his honour? That would be a charming idea, lord father!”

Here the frugal duke felt compelled to intervene. He had no inclination to approve the expenditures required for a celebration lavish enough to suit Elisabeth’s taste.

“We shall spend pleasant days with him,” he said in a tone which was intended to demonstrate clearly enough that the days would be pleasant, but above all, quiet. “We shall eat and drink well, as always, and you will have time to converse with your cousin. A man who went looking for a wife is certain to have a great deal to tell. He travelled far.”

“Yes! As far as Jülich. That is even beyond Cologne, is it not? Truly a long journey. I hope it was worth his while. I would be so happy for him. The electoral prince did well to rest for a few days with my brother in Marburg. Sitting in a coach for too many weeks leaves hardly a bone in place. – I’ll go tell my handmaidens to start packing.”

The duke watched his daughter-in-law go. Elisabeth was not the sort of woman who would limit herself to inquiring about her brother’s well-being. The duke knew that she was eager to learn what was going on in the world. He hoped Philipp had not also infected Electoral Prince Johann Friedrich with the Martinian plague. Ever since the Leipzig Debate seven years ago, it was clear to the duke that this monk – who last year had even married a runaway nun – posed a grave danger to the church. This disgraceful man was not willing to recognise the authority of the pope and the councils, thereby upsetting the very foundations of the world. If someone should destroy the God-given order, only chaos would remain. The peasants’ revolts had conclusively shown the abyss into which this Luther was leading the world.

The labourers had already been loading the ships on the Elbe for hours when several coaches full of the court household appeared on the riverside. Now colourful waves of ladies and chambermaids, servants and finally the ducal family with all its members spilled onto the banks. Canopies were stretched amidships for the ladies, who immediately ran under them to seek shelter from the sun.

Elisabeth had waited on shore awhile until the ducal family with all its household was suitably stowed on the first ship. Duchess Barbara always looked so anxious on the gangplank, as if she had never been aboard a ship before. Duke George, who had been the first to board, received his wife, followed by Johann and his younger brother Friedrich. Only after the family had taken seats beneath the stately canopy did the rest of the court pour onto the five ships. Elisabeth had preferred to take the last ship and walked nimbly along the swaying plank. She found a seat in the stern where she could watch the hustle and bustle undisturbed.

The past winter had brought with it a great deal of snow and the snowmelt was accordingly considerable. The boatmen on the Elbe had had their hands full with the deluge of brown water in the spring, which carried all manner of detritus and even entire trees along with it. But since then, the Elbe had settled down into still, black depths.

“Would you not like to sit with your family?”

It was Magister Alexius Chrosner, the court chaplain, who had come up to her.

“Thank you, Pater Alexius, that is very kind of you, but I would rather sit back here.”

“Too much hubbub?”

Elisabeth smiled and looked across to the banks, where the horses stood ready on the towpaths. The ropes which one of the boatmen had thrown in a wide arc over the bow of the ship had already been fastened to the tight harnesses of the carthorses. The labourers were testing the moorings, slapping the stamping horses encouragingly on the croup or, if their work was finished, lying in the grass and enjoying a few moments of rest before the arduous work of towing began.

“I only hope we have no serious incidents,” said Elisabeth.

“I think the duke will have ensured that the towpaths are all clear and no major impediments await us. Moreover, I suspect that we shall in any case arrive in Dresden before the electoral prince, for he is accustomed to travel with such a large entourage that he hardly makes any headway at all. As you know, I had the great honour and pleasure of being the prince’s tutor. He was a good pupil, but even then a man with a high regard for the physical comforts. I am truly eager to see if he has added to his considerable girth. Just imagine, he even takes his cook and a great deal of kitchen staff along with him. It seems that once, when travelling as a young man, a dish was set before him that he found entirely unpalatable. Since then he has been mindful not to depend on innkeepers.”

“I am looking forward to seeing him. I wonder what he will have to tell of my brother Philipp in Hesse.”

Finally they began moving. The ships cast off, the moorings between the ships and the horses tautened, and slowly, step by step, they glided down the Elbe towards Dresden. Elisabeth looked into the dark water below her, where air bubbles were floating to the surface alongside the ship’s hull. It was still cool. Elisabeth pulled her coat tighter around her shoulders and leaned against the railing, looking towards the broad river whose opposite banks were lost in the morning mist. A barge moved rapidly downstream.

“Moving downstream in the middle of the river you go so fast. Often faster than you’d like. But here close to the banks one can hardly believe that we shall ever get where we’re going.”

Elisabeth turned back towards the water without speaking, watching the waves from the barge splash up against the ship’s hull. The Elbe had a scent all its own. Elisabeth loved this scent of clear, deep water and drew in a deep breath.

“And where are you going?” the priest asked softly.

Elisabeth looked up as the horses neighed. Something must have frightened them, for the labourers were trying to calm the rearing animals. This was soon accomplished and the ropes tautened once again. The horses pulled with all their might, whips cracked, the delay had hardly been noticeable.

“I have but one destination, and that is generally known. And the fact that I shall probably never reach it is obvious. At the start of my marriage, my mother tried to comfort me, after all, she had also had to wait two years until I came along. But I have already been waiting for all the eight years I have spent with my husband here in Dresden. Hope is slowly but surely vanishing.”

“Pardon me, but that is not what I meant. Perhaps you have another goal which is nothing to do with your station, with the tasks set you by other people?”

“I can hardly think about anything else,” Elisabeth whispered. “Of course I know that I must fulfil my duties. I envy my sister-in-law Magdalene, who has already brought a healthy son into the world, but I am not concerned merely with producing an heir. My concern is to bear a child. Girl or boy, I don’t care. I want to hold a CHILD in my arms. I want to smell my child, stroke its head and feel the downy hair, I want to caress its tiny hands and feet. I want to feel the way it takes my finger in its little hand and holds tightly to it. It is so unjust. I have done nothing wrong, that God should have to punish me so!”

Pater Alexius gave her a sidelong look. He could clearly see her bravely fighting back her tears as she looked unbendingly towards the opposite side of the river.

“Perhaps you should put it all in God’s hands. As you know, our prayer is always “Thy will be done!” I am certain that God loves you and does not wish to punish you. I am certain that you will be able to understand later – and it could be much later, indeed – that it was better so. Be patient! And hold fast to your faith, that you are the child of God, whom he loves unconditionally. You must never doubt that. That is the most important realisation of Martin Luther.”

“You are right, my dear Chrosner. God will do the right thing.”

Dresden, May 1526

Electoral Prince Johann Friedrich had not yet arrived, and this circumstance allowed the duke to make his preparations unhurriedly. Above all, wine had to be brought up from the cellar, for the electoral prince was known to enjoy a good cup of wine at frequent intervals.

The following day, the watchman on the tower signalled the approach of Electoral Prince Johann Friedrich of Saxony. And after about three hours, the long train of magnificent wagons and riders arrived at Dresden Castle. The train of wagons was so long that Duke George suspected Johann Friedrich of already having brought his bride along with all her dowry, but that was not the case.

Pater Alexius had not exaggerated. The procession following the resplendent wagon of the electoral prince seemed unending. There were more than two hundred armed soldiers to protect the wagon, as well as several wagons for carrying the duke’s clothing, gifts, kitchen utensils, supplies, important councillors and scribes. Aside from the scribes and councillors who, like their lord, were allowed to sit under a canopy, everything else was tied down under waxed covers. The wagons were followed by a host of servants who were expected to ensure that all went smoothly, but were often enough hindered in carrying out their duties by force majeure, for they could not ward off thunderstorms and hailstorms.

Elisabeth watched the young man rise sedately from his seat in order finally to have solid ground beneath his feet once more. Although he would not celebrate his twenty-second birthday until June, he already had an air of stolidity about him. One could see immediately that he was partial to his creature comforts. His interest obviously concentrated on the pleasures of culinary delights, however, for his clothing was plain and simple, foregoing all the decorations, ribbons and bows currently in fashion. A servant placed a small step next to the prince’s wagon so that his Grace could disembark as gracefully as possible. He finally set his voluminous body onto the courtyard and beheld Duke George and Duchess Barbara, who were waiting with all their courtiers to receive their exalted guest.

“We are happy to welcome you safely to our castle. We hope you had a pleasant journey,” said Duke George after a slight bow. Duchess Barbara also arose from her deep curtsy, after which the entire court likewise stood up.

“Yes, we did,” said the prince, laughing. “But arriving is still the most pleasant part of a journey.” He had a resounding air of merriment which stood in stark contrast to the duke’s stern rigidity.

“Then we would like to ask you please to enter. Feel yourself entirely at home. We are truly glad that you are honouring us with a visit.”

The ducal family went into the castle followed by the courtiers.

“Incidentally, there is someone here in Dresden who is eager to know how things are in Hesse,” the duke said, trying to adopt a conversational tone.

“Yes, I have many heartfelt greetings to convey and a lovely gift, as well,” the prince called out. Elisabeth came forward and made a deep curtsy, as was proper to her station. When she arose, however, she beamed at him. “Your Grace has news of my brother?”

“Yes, and only the best! We will tell you everything. As soon as we have a glass of wine and a joint of roast before us you can ask us anything you would like to know.”

“I thank you, your Grace.”

“If your husband permits, I would like to lead you to table. Duke Johann? May I?”

“Of course,” said Johann with a deep bow.

“Then we shall meet again at mealtime. I hope you have prepared a bath. I feel as if I must wash off hundreds of miles of dust.”

“Most certainly. All is ready. I am sure, your Grace will find everything satisfactory,” assured the duchess.

Only the closest advisors and servants of the electoral prince followed the court through the front entrance to the castle. The soldiers, many of whom were already familiar with Dresden Castle, brought their horses to the stables and settled into their own quarters.

The coach immediately drove to a back entrance where the more menial servants were already unloading the prince’s luggage and carrying it to the chambers provided for him. Indeed, there was a huge tub of hot water waiting so that the exalted guest could bathe. One of the duke’s servants, who had already seen the prince, had made sure that the maids did not fill the tub too full. The young man with his voluminous belly nearly filled the tub all by himself. What is more, they had already put out a little snack so that the guest would not die of hunger and thirst before supper.

The electoral prince greatly appreciated these courtesies and thoroughly enjoyed his bath, food and drink before donning his formal dress.

It was already nearly dark when they sat down at the festively laid table. The duke had apparently emptied the entire silver chamber and set out all the available tableware which came even close to shining. Silver candlesticks radiated aromatic light, spring flowers and blossoming branches could be seen in costly bowls and the people, too, were all arrayed in their best finery in honour of their illustrious visitor. The prince was the only one to wear a simple garment. No one would have dared mention this to him, yet he seemed finally to feel himself obliged to remark, “Modern apparel is fine and good, but I prefer to wear plain garments. You know, Elisabeth, these ribbons and bows can make a harlequin out of even a hardened mercenary, and they tend to get caught on all manner of things. And what is more, I am large enough as it is. I do not need to get all fluffed up like a peacock looking for a mate.” He leaned back in his chair, which creaked ominously, and stroked his stout belly.

Elisabeth laughed. “I suspect you were successful in finding a bride without getting fluffed up.” The prince leaned towards her and said, “She is young and pretty, as a bride should be. And she is as gentle as one could wish for in a wife.”

“Then you are truly fortunate!” Elisabeth shared his joy. “Such a bride is certain to give you no reason for complaint.”

The prince quietly added, “Yes – and I am certainly not going to reproach her for her exceedingly handsome dowry.” He laughed and winked at her.

“You are indeed good-hearted. Your bride will have no reason for complaint, either.”

“Yes, and I have some quite daring ideas for making our lovely castle in Torgau even more comfortable. When all is finished, you will simply have to visit. You will hardly believe your eyes.”

“And just what is so daring?”

“I shall be able to ride into my topmost rooms, where my wine will be served as if by magic.”

Elisabeth laughed aloud. “How is that possible? Ride into the topmost rooms! You have strange notions. Will it please your father?”

“I’ll be able to convince him. What I am planning is entirely extraordinary. It will impress our guests. Like magic, I tell you, is how my wine will be served.”

“Oh, look, we may not be served magically here, but what is being served is nonetheless quite impressive.”

The tables had been set up in a semicircle so that the servants had enough room in the centre to place bowls and plates laden with delicacies onto the tables. The prince noted with satisfaction that two servants bearing a platter with a huge suckling pig were heading straight for him.

“Let us eat, then, and enjoy our meal!” said Duke George, raising his cup to his guest. Everyone else followed his example. Prince Johann Friedrich also raised his cup. “We thank you for your hospitality. We have rarely had such a pleasant journey.” He emptied his cup in a single draught. Not everyone was able to follow suit. Like most of the women, Elisabeth merely took a sip of her wine.

“And at this juncture we would like to announce that we shall be betrothed to a lovely young lady in September.”

Here all put down their cups and glasses and applauded. Congratulations and calls of “vivat!” erupted. Turning to Elisabeth, he added “But now let us eat at last, otherwise we shall be thin as a wraith by September.”

He had the head cook serve him meat, helped himself to considerably less bread and vegetables and ate with an appetite that had no equal.

“Would you be so kind as to tell us about your bride?” Duke George turned to his guest.

“But of course,” replied Prince Johann Friedrich, as Elisabeth watched gravy run down his beard.

“Her name is Sibylle, the eldest daughter of Duke Johann of Cleve. We shall plight our troth at Castle Burg near Wuppertal in September. The wedding will be the following year in Torgau. And you are all invited!” he boomed. Again, everyone applauded.

“Fortunately, it is not so far from Dresden to Torgau. The journey was certainly wearying, that I can tell you. We even had to WALK! WE were compelled to WALK! The roads were so disastrously poor, one could hardly call them roads. They were all soaked through. It was more like a wretched swamp. It took days before we could carry on. Then one of the supply wagons broke an axle. But at least our esteemed cook was able to make a proper meal. The man is worth his weight in gold. We always take him along when we travel. After all, we have no desire to let some scoundrel of a publican in a roadside tavern poison us with boiled mole.” Again he laughed, loud and merrily.

Elisabeth stole a glance at her mother-in-law. Duchess Barbara was obviously making an effort to smile. One could not scold this man, after all, he was an electoral prince. But Lady Barbara was obviously unable to countenance the prince’s behaviour, either. The old duchess was very concerned about etiquette and manners, which is why she and Elisabeth had clashed more than once during her first days in Dresden. When Elisabeth justified herself by explaining that, in Felsberg and Spangenberg, it was perfectly acceptable to talk and laugh with the servants or to cool one’s arms in a watering trough on hot summer days, her mother-in-law strictly forbade her to say anything beginning with “In Spangenberg” or “In Felsberg”.

Elisabeth took secret pleasure in being able to talk and laugh with the guest without her mother-in-law being able to intervene.

Now that the guests were provided with the necessities and the servants merely had to mind which bowls and cups were empty and needed refilling, three musicians entered the circle. Duke George had spent more money than he had originally planned. It was probably Duchess Barbara who hinted that it would hardly do to provide no music for such a great guest.

The colourfully dressed musicians were masters of their trade. They were allowed to play at court repeatedly, yet were not permanently employed by Duke George. There was a tall one who played flute, whilst the short thin one played hurdy-gurdy and the fat one softly beat a drum. They played quietly so as not to disturb the talk of the company, although all talk soon ceased, for music was a rare treat at this court. The three men in the centre wove a tapestry of sounds which floated like variegated ripples in the honey-coloured candlelight.

“My bride likes music, too. She even plays several instruments. Admirable. Truly and genuinely masterful,” whispered the prince without taking his gaze from the musicians. Elisabeth smiled. Johann Friedrich was quite delighted by his future wife. She only hoped that the feeling was mutual. She herself was still having trouble accepting the fact that she had been promised and all contracts signed when she was still a baby and unable to put in a word of her own. In the meantime, however, a certain mutual respect had grown between herself and Johann. That was at the least more than could generally be expected. Love did not feature in the equation. Elisabeth sighed and reached for the sweet cake. She still had to wait quite a while before the board was cleared and the partakers of the feast would meet in the middle for the dance, stroll around the edges or gather into small groups to chat. Elisabeth loved to dance and planned to spend a great deal of time dancing this evening, for instance with the electoral prince and her brother-in-law Friedrich, Johann’s only brother still living at court. The other brothers had all died, and the sisters who had not yet died had married and gone off with their husbands. Elisabeth was quite fond of Friedrich. He had quickly grown on her and appeared to her like a pale image of her husband, for Friedrich was even more awestruck and fearful towards his father than Johann. Whenever she had a friendly talk with her father-in-law, or even laughed with him, she saw unabashed admiration in his eyes, as if he were marvelling at some daredevil trying to tame a wild animal. Perhaps she would also dance with her spouse, if he was not too exhausted. He had been of a weak constitution even as a boy, and had sadly not improved.

The musicians began with a pavane, a slow dance much to the liking of the elders, since one need only take dignified steps and raise the heels from time to time, with no danger of perspiring. The electoral prince asked Duchess Barbara for the first dance, whereupon Duke George offered his hand to his daughter-in-law.

“It will be an honour for me, my Lord!” she said, and took the hand he offered.

Johann apparently felt obliged to make up ground, for he asked Countess Köstritz to dance. She took his hand rather stiffly and gave Elisabeth a brief, but still very angry, glance, which caused Johann to give up any hope of ever moving her to resume her position as Elisabeth’s hofmeisterin. Johann was kindness itself, bowing to his partner with an especially amiable smile and matching his steps to hers, which finally softened the elder lady’s mien somewhat.

It was readily evident that Elisabeth found the pavane a bit too tame for her taste and was looking forward to the coming galliard. She not only lifted her heels, but leapt aloft and was relieved when the slow pacing finally came to an end. Duke George brought her back to her seat, but Albrecht, a young courtier, immediately stepped up and asked her to join him in the galliard. Albrecht was a servant of Duke Johann; a minor nobleman whose origin had not been of great interest to the young duke until his wife Elisabeth obviously noticed that this young man was an exceptionally good dancer.

More couples paired up and took their places whilst the musicians retuned their instruments. Duke George and Duchess Barbara withdrew to their seats, as did many others, and watched as Elisabeth and this courtier, whose name they had not even bothered to note, went through the spirited steps of the galliard. Johann stood at the window and tried to look as aloof as possible. Lady Köstritz did not fail to take notice of Elisabeth’s dancing, of course, nor did Messrs. Schönberg and Schleinitz, who looked at each other with a disapproving shake of the head. (Schönberg was annoyed that the hofmeisterin had strictly refused to reveal Elisabeth’s rhyme to him, as well.) Such wanton behaviour could only be a consequence of Martinian doctrines. If her brother Philipp was already an openly declared follower of Luther, then this Elisabeth was surely not far removed from the same. Here one could see what happened when people turned away from the old order: it started with wild dances and led inexorably to peasant uprisings.

The other young couples, however, were obviously enjoying the dance, as well, since it was much more to the liking of their youthful nature. The candlelight made the silken gowns shimmer mysteriously, the jewellery flashed and the flautist now took up his bagpipe to drown out the noise of many jumping feet.

Following the galliard, the musicians played a somewhat slower allemande to give the dancers a chance to rest. Now Elisabeth danced with her husband. She did so with pronounced friendliness to stop the wagging tongues of her adversaries. At every curtsy and bow, she beamed a particularly loving smile at her husband so that no doubt could arise as to who owned her heart, but this, too, was construed as improper. As Lady Köstritz remarked, pressing her lips even more firmly together, it simply did not do to make eyes at one’s spouse as if one were newly enamoured,!

Then Elisabeth danced with the prince and Johann asked one of the ladies of the court to dance. Elisabeth noticed that the prince was breathing heavily at every step and jump. Perspiration was running down his forehead and cheeks and into his collar.

“Should we rest for a while?” she asked.

“No, no. There is no need,” he replied, panting.

“I would very much like a drink and some fresh air,” Elisabeth insisted and saw that Johann Friedrich was visibly relieved when the dance ended and he was able to leave the dance floor.

They went to one of the open windows, where a servant offered them a tray of filled goblets. Now Elisabeth felt safe from eavesdroppers. The music was loud enough to keep their words from being audible from a distance.

“Now tell me of Hesse! How are my brother and his wife? I haven’t been allowed to see them for ages!” Elisabeth asked, and took a sip from her goblet.

“What? Not allowed to see them? Does the duke forbid it?” Prince Johann Friedrich was visibly surprise.

“He does not specifically forbid it, but nor does he allow it. Something always comes up. Now war, now plague. That I can understand. But then there is poor weather, which I could easily take steps to bear. Or the only coachman to be found in all of Saxony has a toothache or his wife has her washing day or the horses have ingrown toenails. Something always comes up. All my pleading and begging is for naught. But now, tell me, please!”

The prince guffawed. When he had finally calmed down, he replied, “Your brother and his wife are doing very well. They are both in good health. And I have brought you something from him. A gift.”

“A gift for me?” Elisabeth asked in surprise.

“Yes, and it is something very special,” Prince Johann Friedrich whispered.

“A box made of wood. But there is more to this box than meets the eye.”

“What do you mean?”

“The box, which is sumptuously wrought, has a false bottom. Your brother has hidden something in this bottom which is sure to delight you.”

“Then I am eager for it! Are they soon to have children?” she quietly added.

“No, as far as I could tell, your sister-in-law is not with child.”

Elisabeth looked silently at the floor. The prince was uneasy. Pregnancy was a sensitive topic with Elisabeth.

“Your brother has great plans,” Johann Friedrich then attempted a distraction.

“He wants to get the Reformation underway and hopes that the emperor will soon have to create the necessary conditions, even though he does not want to.”

“I hope I am not intruding!” said someone they had not noticed.

“Pater Alexius!” the prince exclaimed in delight. “I had hoped to find you here. I was delighted to hear that Duke George had named you court chaplain despite your Martinian views.”

“The duke always listens to my sermons with benevolent interest, but his Grace would watch a rain dance performed by New World savages with the same interest, I am sure. So I need not get my hopes up. Nonetheless, he would rather allow me to persuade him than join in the dance with the savages – or so I hope.” Elisabeth and the prince laughed. “I believe Duke George would open himself up to persuasion if not for his councillors, who are constantly filling his ear with all this Roman Catholic nonsense.”3

“Elisabeth, you are certain to know that Pater Alexius was my teacher. He had his hands full with me, I can tell you that!”

“Now, now, your Grace, it was not all that bad. I made every effort to teach you a bit more than the bare minimum,” the priest said, bowing.

“And I would say you were successful,” Elisabeth responded. “We had just now come to a subject that is sure to interest you, as well. Emperor Charles finds himself in difficulties,” said Elisabeth, and Johann Friedrich added, “Yes, the emperor is not all-powerful. And more and more princes are adopting Martinian beliefs. The emperor could soon find himself in a situation where he is dependent on the Martinian princes.” Pater Alexius looked around. A confidante of the old Duchess had drawn near. The three fell silent and watched as a juggler moved to the centre of the hall and bowed deeply. Suddenly he was holding multicoloured balls in his hands which he seemed to have pulled from behind the ears of one of the ladies and began to juggle them.

Elisabeth watched the juggler’s hands, which handled the balls as surely as if they moved at his command. She saw his unshaven neck, his Adam’s apple bobbing up and down; how he followed the flight of the balls with his eyes and make jokes all the while. Elisabeth hardly noticed that her hand was clasping the locket of violets around her neck. She shook off the memories and longings and watched the juggler with Johann Friedrich.

Elisabeth hardly noticed that her hand was clasping the locket of violets around her neck. She shook off all her memories and yearning and, along with Johann Friedrich, just watched the juggler. The two laughed at his capers and acted as if nothing interested them more than the flight of his brightly coloured balls. Pater Alexius also watched, but confined himself to a kindly smile. When the lady had passed and they felt safe again, the Pater said, “Then I am right in assuming that these difficulties could prove advantageous to our Martinian cause.”

“Quite right. The emperor has not been able to pay his troops for some time now. He is at war with Francis I of France. Each of them are claiming territories in Upper Italy. Two years ago, the

emperor laid siege to Marseilles, but was unsuccessful. His troops finally had to give up the siege and withdraw. They were attacked by French troops and pushed back to Pavia, but then the tide turned. Charles was able to defeat the French and capture their king. He forced Francis I to sign a peace treaty giving the territories in Upper Italy to the emperor. And then he let him go free.”

“What a ploy!” Elisabeth said, rolling her eyes. “And once he was free, Francis surely wasted no time declaring the treaty null and void, didn’t he?”

“Of course, And in this he was supported by the pope. Charles’ councillors had advised him against letting the king go. They did not trust the French, but Charles had apparently appealed to the king’s sense of honour.” The prince sounded almost as if he pitied the emperor.

“The emperor seems to come from another world. That is so outmoded! His grandfather, Emperor Maximilian, was already fighting for the territories in Upper Italy.”

“Yes, and Maximilian wore himself out in the attempt,” said Pater Alexius.

“But if the emperor no longer has the territories in Upper Italy, he will have to keep fighting for them, and that costs money, doesn’t it?” Elisabeth conjectured.

“Exactly. He could well have used the spoils of this war to pay his troops.”

At this moment, Messrs. Schönberg and Schleinitz approached. Elisabeth had seen them out of the corner of her eye and now called out, “Why, your Grace, you don’t say! Covered all over with ribbons and bows? That must look lovely. I will order just such a dress tomorrow, and what are they putting on their heads in the great city of Cologne?”

“Embroidered bonnets. And to make them match the dresses, the bonnets too are covered over with embroidered ribbons,” the prince went along with her diversionary tactic.

“I don’t know that I approve of so many ribbons!” said Pater Alexius loudly and in a clearly peeved tone of voice.

Schönberg and Schleinitz could find no reason to walk even more slowly and finally passed out of hearing, just as the others began to hold forth about beribboned shoes.

Elisabeth laughed to herself. “Ribbons! Good! Now where were we? Ah yes, Charles. What sort of men does he have fighting for him?”

“His army consists of German, Spanish and Italian mercenaries. These men all fight for money. But they haven’t been getting regular pay for two years now,” Johann Friedrich reported.

“How strong is the army?” Elisabeth asked.

“Estimates range between twenty and thirty thousand men. So it will be around twenty-five thousand.”

Chrosner’s face took on a serious look. “Twenty-five thousand unpaid mercenaries. That sort of host is like a rabid dog that no master can tame any longer. And this host is providing for itself, is it not?” The electoral prince nodded darkly.

“It is hard to imagine what that must mean for the common people. In a war like that not only do the battlefields get ravaged, but wherever this host rolls through it leaves swathes of misery and death in its wake.” Alexius Chrosner was still for a while. His eyes took on a depth which Prince Johann Friedrich had rarely seen in them. He seemed to be looking far away in time.

“Have you yourself lived through such devastation?” he softly asked.

“I think I have only had a small taste of what the people in France, Italy and other parts of Germany have been enduring for years. But however that may be, Charles is in a predicament. He has to pay his men or they will all leave him – if he’s lucky. He needs the German princes. All of them. He cannot rely on the Catholics alone. He needs the Martinian nobles, as well.”

“A diet is already scheduled for next month in Speyer. He will have to make concessions there.”

“Do you mean he will rescind the Edict of Worms4?” Pater Alexius said hopefully.

“That would not only be too good to be true, but also the most obvious course to take. If he were truly to lift the imperial ban on Luther ...”

“Then my brother could make Hesse Martinian in a trice.”

“He could indeed!” the pater concurred.

“Let’s drink to that!” said the prince, raising his glass.

Many candles had already burned down and not all had been replaced by new ones. In the twilight of the hall, the musicians had again taken up their places and were playing a volta.

“There’s something else I have to tell you,” the prince began, but Elisabeth’s eyes were already scouring the hall for a certain Albrecht, so she no longer heard the prince’s words.

“Forgive me, I shall return shortly!” she said, setting down her glass to hurry over to Albrecht, who readily took his place in line across from her for the dance. The courtier smiled at her and lifted her in time to the music so that her skirts billowed. Even after dancing for hours, he was neither out of breath nor was his long hair dishevelled, nor did his fashionable clothing show any perspiration stains. In a word, the man was indestructible. Who could be surprised that the entire court was wondering what other activities he could perform with such stamina?

Elisabeth was probably the only one who never thought about this, for she danced and laughed with him as ingenuously as if it was the most natural thing in the world for the Duchess of Saxony to dance with one of her husband’s manservants. Only Pater Alexius Chrosner and the electoral prince watched the two of them with smiling faces. As they watched, the dancers seemed to be a carousel turning ever faster. The dim light of the candles made their silk attire shine, and sometimes it even looked as if tongues of flame were dancing over their ever more wildly swaying garments. They saw the ladies place their hands on the men’s shoulders while the men grasped the ladies around their waists to lift them up with a forceful sweep that set their skirts to flying, allowing flashes of the bright underclothes to be seen. Johann Friedrich’s eyes wandered over to Duke George and Duke Johann, who were observing the wild goings-on with stony faces. Right next to the elder duke Schleinitz and Schönberg stood, exchanging invidious glances and whispering secretly together. They were most probably commenting on Elisabeth’s petticoats, which this dance quite visibly displayed. Lady Köstritz sat in a group of other court ladies and looked as if she had a bad taste in her mouth while she observed Elisabeth and had to crane her neck whenever Elisabeth and Albrecht were hidden by one of the other dancing couples. Pater Alexius’ gaze followed that of the prince.