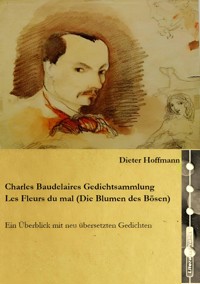

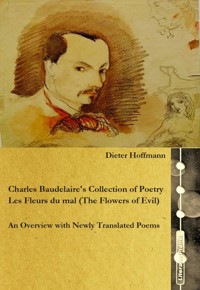

Charles Baudelaire's Collection of Poetry Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil) E-Book

Dieter Hoffmann

4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: LiteraturPlanet

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Charles Baudelaire's poetic flower garden exudes many different fragrances. The most exquisite of them enable us to achieve what Baudelaire regarded as the most noble goal of his poetry: they allow us to "catch a glimpse of paradise". The present book offers an exemplary overview of Baudelaire's poetic flowers, combined with commentaries based on Baudelaire's own poetological and philosophical reflections.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Dieter Hoffmann:

Charles Baudelaire's Collection of Poetry

LesFleurs du mal

(The Flowers of Evil)

An Overview with Newly Translated Poems

Literaturplanet / Planet Literature

Imprint

© LiteraturPlanet, 2024

Im Borresch 14

D-66606 St. Wendel

www.literaturplanet.de /www.planet-literature.com

About this book: Charles Baudelaire's poetic flower garden exudes many different fragrances. The most exquisite of them enable us to achieve what Baudelaire regarded as the most noble goal of his poetry: they allow us to "catch a glimpse of paradise". The present book offers an exemplary overview of Baudelaire's poetic flowers, combined with commentaries based on Baudelaire's own poetological and philosophical reflections.

Für die Übersetzung wurde deepl.com als Hilfsmittel eingesetzt. Alle Texte wurden nachredigiert. Die Gedichte wurden frei ins Englische übertragen ohne KI– Hilfsmittel .

Information about Dieter Hoffmann can be found on his blog (rotherbaron.com) and on Wikipedia.

Cover picture: Charles Baudelaire: Self-portrait (1848); Paris, Musée des monuments français (Cité de l'architecture et du patrimoine); Wikimedia Commons

1. Introduction

Charles Baudelaire (photogravure; Wikimedia Commons)

A Groundbreaking Work

Charles Baudelaire's collection of poems Les Fleurs du mal was first published in 1857. Two further editions were published in 1861 and 1868, each with additional poems.

Les Fleurs du mal is undoubtedly an epoch-making work. The poems significantly influenced both the later literature of Symbolism and the turn-of-the-century literature of the Décadence. Above all, however, Baudelaire coherently characterised the state of mind of his contemporaries in his poems. At the heart of this was the feeling of disorientation caused by the rapid changes resulting from industrialisation and the associated transformation of the prevailing world view.

As Baudelaire thus reflected the attitude to life in modern times in his poems, they do not sound antiquated even today. This is also evident in the numerous musical settings of his works, to which new ones are constantly being added.

Unbiasedness as a Prerequisite for Intellectual Originality

However, Baudelaire has also become a bit of a victim of his own fame. Precisely because he is so well known, people think they know everything about him and no longer approach his poems with an open mind.

Yet Baudelaire himself described an unbiased view of the world as a decisive prerequisite for intellectual originality. The detachment from the conventional world view was a process of spiritual "recovery" for him. In his view, the artist thus regains the ability to see the world with the curious eyes of a child, for whom the world is new at every moment. The exhilarating joy and lively interest with which the child encounters the world are also the decisive sources of inspiration for the artist. In Baudelaire's words:

"For the child, everything is new; it is always in an exhilarated state of mind. Nothing comes closer to what we call inspiration than the joy with which the child absorbs forms and colours" (PVM III).

Consequently, the present book attempts to look at Baudelaire's "Flowers of Evil" once again with such an unbiased, childlike view. To this end, his poems will be considered against the background of his own poetological and philosophical reflections and presented in new adaptations. The chapters of the volume are organised according to the different aspects of the Fleurs du mal – which are by no means limited to the concept of "evil".

Poetic Adaptations as a "Tender Dream"

On the occasion of his translations of works by Edgar Allan Poe, Baudelaire himself pointed out that even the most endeavoured, most subtle translations of poems into another language could never be more than a "tender dream" ("un rêve caressant"; cf. NN IV). The resulting poems are basically always something new, which is merely based on the foreign-language work, while necessarily interpreting it through the transformation into the other language. This is shown not least by Baudelaire's own poems, of which there are numerous translations in several languages.

Thus, new translations of Baudelaire's works are dispensable for those who simply want to get a cursory impression of their meaning. On the other hand, each new adaptation leads to at least a slightly different accentuation of the meaning, as it is based on the individual appropriation process of those who "transpose" the works in question into their own language.

Since this process of appropriation takes place not only within the framework of a different culture, but also against the background of a new time, the poems' meaning for the respective present becomes far clearer than it could ever be in the original language. For in the original language, the poem always remains bound to the form that the poet has chosen for it.

Thus, a new translation can perhaps also give a poem back some of the "strangeness" that Baudelaire regards as the "indispensable flavour of all beauty" (ibid.). In a new poem, this strangeness can be achieved through novel metaphors or surprising rhymes. In the case of older poems, however – especially if canonised – there is always the danger that the initially fresh and surprising effect will wear off through habituation. This effect can only be mitigated by new forms of presentation, such as a new musical setting or a new translation.

On the Adaptations Presented in this Book

For my own adaptations of poems from the Fleurs du mal, I took the liberty of dispensing with rhymes. Instead, it was important to me to reproduce the subjective mood of the lyrical self as expressed in the original text.

In this context, I also draw on Baudelaire's own poetic ideal, according to which the meaning of poetry is based above all on its ability to subject the "fleeting demon" of emotional states to one's own will in such a way that the resulting poem can put the reader in a corresponding "state of excitement" (ibid.).

Links to the French originals are included with each of the adaptations. In addition, reference is made to musical settings of the poems in question. An overview of the numerous musical interpretations of Baudelaire's works can be found on the website of the Baudelaire Song Project (baudelairesong.org) and on Wikipedia:Mise en musique des poèmes de Charles Baudelaire.

2. The Fleurs du mal – Flowers of Evil?

Charles Baudelaire: Self-portrait smoking a hashish pipe (1844)

Paris, Bibliothèque des Arts Décoratifs (Wikimedia Commons)

The Cliché of the "Poet of Evil"

Baudelaire's epochal volume of poetry Les Fleurs du mal is commonly translated as The Flowers of Evil. Such a translation is justified insofar as Baudelaire himself explicitly regarded the category of evil as a central driving force of human action. Some of the poems in the Fleurs du mal are indeed clearly influenced by this view of human nature.

On the other hand, the Fleurs du mal only represent a sub-cycle within the entire collection of poems of the same name. In addition, there are other sub-cycles whose titles (including "The Wine" or "Parisian Pictures") indicate a more complex conception of the collection of poems.

The limitation to the aspect of evil therefore entails the danger of following clichés that were already spread by Baudelaire's critics during his lifetime – which was one of the reasons why some of his poems were temporarily banned. The poet himself was considered "evil" or at least wicked, because he dared to depict the flipside of bourgeois society in his poetry, i.e. that which was "evil" from its perspective: the beggars, the whores, the good-for-nothing drifters, the sick, the drunkards and the enthusiasts of other drugs, but also ageing and death.

Ambiguity of "le mal"

It is therefore worth recalling that the meaning of "le mal" is by no means limited to "evil". In numerous expressions, the term also refers to pain, sorrow and physical discomfort. For example, "le mal du pays" points to homesickness, and those who have "mal au cœur" are not necessarily suffering from heart pain, but possibly just from nausea. This makes the image of the Fleurs du mal more colourful than it appears in the usual translation as "Flowers of Evil".

In many of the poems in Les Fleurs du mal, "le mal" is more an image for a bad mood than for an evil character. The best proof of this is the fact that there are no less than four poems in the poetry collection with the title "Spleen" (in the sense of a "gloomy mood"). The fourth of these is presented below. The poem was set to music by the famous chansonnier Léo Ferré on his double album "Léo Ferré chante Baudelaire" from 1967.

Poem: Melancholy

(Spleen 4; FM 80, p. 202)

When, like a coffin lid, the sky

weighs down on the earth, chaining the mind

to the eternal night that stretches out

from horizon to horizon;

when hope, like a captured bat,

beats against the dungeon walls

of its world, and eerily its flapping wings

echo through the tomb of the earth;

when the rain, shaking its sallow wings,

encloses every path with barren bars,

and melancholy spins insidiously

its midnight thoughts around our hearts –

then the bells with angry, groaning sound,

like forsaken souls, wandering homeless

through heaven and earth,

cry out their speechless prayer into space.