13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

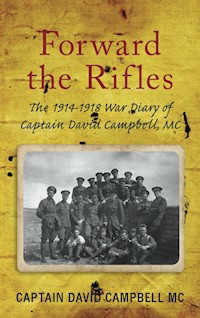

The battlefields of Gallipoli and Salonica were a far cry from life on a small working farm in County Louth, Ireland, and yet, in 1915, Captain David Campbell, M.C., 6th Royal Irish Rifles, found himself in the searing Turkish heat, confronted by a faceless and seemingly tireless enemy. Less than twenty months after joining the Officers' Training Corps in Trinity College Dublin, Campbell led his company over the arid ground to the Front. From the beginning he kept a diary, describing life in these two theatres of war in great detail. Forward the Rifles is that diary. In it, he encapsulates the frightening scale of warfare, and yet he managed to find humour in the simple acts of himself and his men, as they trudge through daily life, trying to keep their bodies nourished and their spirits buoyed. The story of Captain David Campbell is one that will ring true for many, and yet it is an intensely personal one, chronicling his recovery from the physical and mental wounds of battle. Now, more than three decades after his death, the unswerving loyalty, courage and kindness of Captain David Campbell, M.C., are reborn.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Forward the Rifles

Forward the Rifles

Captain David Campbell, M.C.

16 November 1887 - 10 April 1971

6th Royal Irish Rifles

First published in 2009

The History Press Ireland

119 Lower Baggot Street

Dublin 2

Ireland

www.thehistorypress.ie

This ebook edition first published in 2012

All rights reserved

© The estate of Captain David Campbell, 2009

The right of David Campbell, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 8098 5

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 8097 8

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Introduction by David Henry Campbell

1 Outbreak of the Great War

2 We Embark for the Dardanelles

3 Gallipoli

4 Evacuation

5 Highclere Castle

6 Home on Leave

7 Return to Active Service

8 Salonica

9 Back to Hospital

10 Hospital Ship to England

11 Back in England

12 Epilogue: I am retired

13 Rehabilitation

14 Return to Trinity College

Introduction

David Campbell, my father, was a young man living on the sixty-acre family farm, Crinstown, three miles from Ardee in Co. Louth, in Ireland. His father had died in 1895 while out working in the fields and his mother had brought up the family of eleven on her own. As a boy he had walked those three miles to school in Ardee every day and as a young man he had been a school teacher and had then entered Trinity College, Dublin as a divinity student.

The year was 1914 and the world was about to be engulfed in the Great War, ‘The war to end all wars.’ Ireland was then part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and my father, in addition to being a divinity student, was also a member of the Trinity College Officers’ Training Corps. So it was that shortly after the outbreak of war he received his orders to report to the Officers’ Training School.

Like many Irish soldiers his service took him to Gallipoli, where countless men, many of them Irish men, lost their lives. It was said that after the landings at Gallipoli, black crepe hung from every door in the Coombe in Dublin. He was wounded and was evacuated to England where he recovered. His account of his training and of his service in Gallipoli and later in Salonica is an intensely personal one.

The end of the war brought a period of great change in the world and particularly in the United Kingdom, where the twenty-six counties of Ireland became an independent sovereign state. After the war my father became a civil engineer. Within his lifetime the flimsy aeroplanes that had flown during the war were replaced by great passenger airliners that could fly over the Atlantic. They needed a major airport in the West of Ireland and he was appointed resident engineer to construct what was to become Shannon Airport.

David Henry Campbell

October 2009

1

Outbreak of the Great War

4 August 1914

On 4 August 1914, together with the morning paper announcing the outbreak of the war, I received a letter from the Officers’ Training Corps, Trinity College, Dublin, inviting me to apply for a commission in the Army. I was twenty-seven years of age.

I had entered Trinity in January 1913 and had joined the OTC in March 1914. So it was that my name was on the books of the War Office; so it came about that I received that fateful letter.

I was working for ‘Little Go’ at the time, my intention being to enter the Ministry of the Church of Ireland, and having considered the subject for a few days, I consulted the Rector at Ardee. I have forgotten what advice he gave me, but the upshot was that I duly submitted my application for a commission. Having done so and having waited for my excitement to subside I tried to resume my studies. It was not for long.

On 26 August, as I sat at a table on the lawn, swotting Greek, Amelia came in through the garden gate with a letter in her hand which she had just received from the postman. ‘Second Lieutenant David Campbell’, she announced.

I rose from my seat, took my Greek lexicon in my two hands and kicked it high in the air. ‘I’ll never open you again’, I cried. And I never did resume the study of Greek, though I was just beginning to love the language at the time.

The letter was from the King. ‘George by the grace of God’, I read, ‘of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland’, etc. ‘To our Trusty and Well-beloved David Campbell, Greetings’. It was my commission.

When I first applied, I do not think I was inspired by lofty motives. I had no feeling of ‘wanting to do my bit’ or ‘wanting to fight for my country’, or ‘wanting to serve my King’, or any hatred of the Germans or any feeling of patriotism. I think I just wanted to escape from the drab life I was then leading. I had not worked hard enough for my exam. I had spent my time, too much of it, gadding around the county, going to tennis parties, dances and what not, and I was very much afraid I would not pass my ‘Little Go’. And so, when the call came, I was ripe for a change and accepted it with joy.

The letter also contained my orders. I was to report forthwith to the Officers’ Training School, which had just been established in Trinity. I took my orders literally and at once made preparations to obey them. Indeed I was one of the first to arrive at the school. In a day or two, however, the class was complete.

We were accommodated in tents but had to provide our own camp beds. Tragedy overtook mine on the first night of its service. Two hefty blokes, they must have been sixteen stone apiece, came to visit one of the other occupants of my tent. They had been out on a pub crawl and were pretty well oiled. Mine was the only bed set up at the time and down they sat on it beside me. It was never meant to carry such a load and sure enough something gave under the strain. For ever after, whenever I slept in the bed I could feel those legs sticking into the small of my back.

Most of the 300 or so who attended the school had been in the OTC for some years and were well acquainted with the rudiments of soldiering. I, however, was a complete novice. When this was discovered, one of the instructors carried me off, stealthily, I thought, to a remote corner of the camp and gave me my first lesson in military drill. ‘Right Turn!’, ‘Left Turn!’, ‘Quick March!’, ‘Halt!’ I picked it up quickly and soon felt the complete soldier.

In order to clear the books, those who went into the Army had to be discharged from the OTC. When it came to my discharge, it was found that I had not attended any parades. Now, the OTC gets a bonus for every cadet who attends a specified number of parades and passes an Efficiency Test. As I had done neither, I had to be graded as ‘Inefficient’ and to pay up the amount of the bonus, £5. I was fool enough to pay up, for I am sure I would have been excused had I pleaded inability to pay.

The incident became a legend in the OTC, and at the first Armistice Dinner, held in Trinity on 11 November 1919, the chairman in his speech said, ‘And here is Campbell, discharged as “Inefficient” in August 1914, and given a commission, and he comes back as Captain and with his breast covered with medals.’

After one month’s training, I had caught up on most of the others and, like them, was passed out and posted to a battalion. Mine was the 6th Royal Irish Rifles, then stationed at Fermoy, Co. Cork. I reported for duty on 4 September and was placed in command of No.2 Platoon.

I felt pretty green as I prepared to face my platoon on my first parade. My batman, an old soldier, a regular, and highly efficient, had me out of bed at 6a.m. that first morning. ‘Your bath is ready, Sir’, he said. He had carried the water up a couple of flights of stairs and poured it into a bath tub which now stood steaming in the middle of my bedroom floor. I hadn’t the courage to tell him I didn’t want a bath just then. And so it was for many a long day. He took command, saw that I was properly dressed before I went on parade, saw that I was dressed in time for dinner, valeted me, looked after my clothes and equipment, held himself responsible for my conduct, and indeed took complete charge of me. I believe the RSM would have had him on the mat if I happened to put a foot wrong. I rather liked having a valet. During my four years in the Army and, later on in life, my six years in India, I enjoyed that privilege. Even to this day, thirty-eight years later, when I have to clean my own shoes, or put studs in an evening shirt, or put away my clothes, I have a nostalgic yearning for the days when I had someone to do those sorts of things for me.

But to my task. At 7a.m. on that first morning, I found myself standing in front of a platoon of about seventy men. To say that I was a bit scared is to put it mildly. As a matter of fact I was scared stiff. That first parade, however, consisted of Company drill and doubling round the barrack square and, as I got warmed up, I lost my nervousness. I learned the words of command quickly enough and before very long I could handle my men with the confidence of an old hand.

My platoon looked a pretty tough lot. Most of them, as I learned later, were reservists and were accustomed to being called up annually for a month’s training. Many of them were middle-aged and beery looking, the sort whose main interest in life was ‘the price of a drink’. They were not easy to manage at first. They hated violent exercise. Physical jerks and doubling round the barrack square were anathema to them. The regular exercise and the ample food, however, soon began to tell and before very long they began to face their work cheerfully enough, and later to take a pride in their smartness.

I have in front of me now a group photograph of the officers, taken on 10 September 1914. There were fourteen Regulars and seven newly commissioned men who, like myself, had just joined after having had a month’s training or so. We were lucky in having so many Regulars. Most of the Senior NCOs were also Regulars. We had not yet our full complement of junior officers but I think that by Christmas we had reached full strength. We were worked pretty hard in those early days. It was a case of physical jerks every morning from 7.00 to 8.00, parades 8.30 to 12.30 and 2.00 to 5.00, lectures in the evenings, route marches, sham battles, night operations, there was no respite. We newly appointed Temporary Officers, took our work very seriously. We were keen to win our spurs, as it were, keen to prove ourselves and to win the confidence of our seniors. And, by all accounts, we made marvellous progress. When we were not attending lectures, many of us spent our off hours in our rooms, where the Manual of Infantry Training and the Manual of Field Service became our constant companions. We rarely went over to the town. Indeed I can remember only one occasion when I did so.

There was one snag, one fly in the ointment. When I joined the battalion, the pay of a Second Lieutenant was 6s 8d a day and messing cost 10s a day minimum. To those of us who had no income, this placed us in a somewhat embarrassing position. It was not too long, however, until the position was rectified by raising our pay to 10s a day and cutting the messing to 7s 6d. In the case of the men, at that time a single man was paid 7s a week and a married man 3s 6d, the other 3s 6d being compulsorily retained and sent to his wife. In these circumstances there was little danger of any of us new recruits, officers or men, collecting a ‘head like a concertina’ or a ‘tongue like a button stick’.

On 8 October we moved to the Royal Barracks, Dublin, and continued training on the same lines. We did a lot of our work in the Phoenix Park, which was quite close at hand. There we practised advancing to the attack in open formation and by short rushes, taking cover, patrol work, scouting, etc.

We also went for long route marches, twenty miles or so, and with both officers and men in full kit and carrying iron weights in our ammunition pouches. The latter we regarded as a great hardship and it is not surprising that the beastly iron weights often went missing. Though I never fell out on a route march, I was not all that good a marcher and I often suffered a good deal. My feet blistered easily and I tired more quickly than some of the others. The procedure on a route march was to halt and rest for ten minutes every hour. I used to say I could sleep for eight of those minutes.

Soldiers of the 6th Royal Irish Rifles, stationed at Fermoy, Co. Cork.

Early in the New Year a batch of promotions came through. All the regular lieutenants were made captains, including our Company Commander, J.F. Martyr. Like many of the others, he had been waiting over ten years for his captaincy. He had also been engaged to be married for a number of years but could not afford to do so. Now he wasted no time; he got married as soon as he became a captain and stayed with his wife at the Royal Oak Hotel, near the Royal Barracks. One evening he invited me and the other officers of his company to meet his wife. I don’t think I ever saw such a devoted and happy pair. But tragedy was close at hand, for he died of wounds after that fateful day on Gallipoli in August 1915, when the battalion went into action for the first time. We mourned the loss of a gallant officer and true friend. But what was our loss to that of his adoring wife who had waited so long for him?

Three other second lieutenants, Pollock, Brogden and McGavin, and myself were also promoted at that time. We were made Lieutenants. Another officer, G.B.J. Smith, who was gazetted on the same day as myself, 26 August, thought it most unfair that I should be regarded as senior to him and given my second pip before him just because of the fortuitous circumstance that my name began with a ‘C’ and his with an ‘S’.

We fired a musketry course at Bull Island, Dollymount. The rifle range was at the north of the island. That was in the month of February and as far as I can remember the weather was fairly good. We used to march to the range, a distance of about ten miles. We were in good fettle by then and enjoyed the marches very much. The pavements rang as we swung along Ormond Quay and Bachelors Walk behind the band which usually accompanied us as far as O’Connell Street (then called Sackville Street). It was quite exhilarating.

We had to skirt the Royal Dublin Golf Links as we approached the Butts. I had begun to learn golf before the war broke out and the links attracted me. Then one day as we marched past, I saw a man drive off from a tee. It gave me the thrill of my life. Straight as a bullet the ball went. And what a length! I lost sight of it before it reached the end of its flight. To this day I can see that ball in the air.

On days when we marched to the Butts, we came back by tram, specially provided by the Dublin United Tramway Company (DUTC), ‘specially’, because we generally were a party of two or three hundred. In those days the trams were open topped.

While stationed in Dublin, I, and most of the junior officers, led a quiet life. Most evenings found us in our rooms studying our military manuals or attending lectures. I do not remember going into town or to a show of any kind on any one occasion, though I do remember going to a service in St Patrick’s Cathedral a few times.

Early in February we marched to the Curragh in full kit. On the first day we went as far as Naas, a distance of nineteen miles. How well I remember that march. Every here and there the road had large patches of loose stones, and as the columns of four marched over them, crunch, crunch, crunch, you could hear the muttered oaths, swear, swear, swear. At Naas we billeted in the military barracks for the night. Pollock, McGavin and I were allotted a kitchen in the Warrant Officers’ Quarters. It had a fire and a tiled floor. Wrapped in our great-coats, we huddled together on the floor, taking it in turn to wake up and tend the fire. It was a bitter cold night but, wearied as we were by the long march, we slept in spite of the cold and the hardness of the tiles. The chief trouble was to wake up in time to tend the fire before it went out.

The ten-mile march from Naas to our campsite at French Furze, near the western boundary of the Curragh, was even more trying than the nineteen-mile march of the previous day. As we left the shelter of the roadside hedges behind, after passing through Newbridge, with not a hedge or a tree in sight, we were met by a regular blizzard. A gale of wind blowing straight into our faces and drenching rain almost brought the column to a halt. The column was five or six hundred yards long and when a great gust hit it you could see the effect as the gust travelled along it, bending it till it almost looked like a long, wriggling snake. At times, parts were almost swept off the road. The waves reminded me of the waves set up in a meadow in the month of May when a breeze sweeps across it – a phenomenon I always loved to watch.

On arrival at the camp we found the whole place a sea of mud. There were lines of huts, each large enough to hold about fifty men. While they were under construction, the ground about them was cut up by the contractor’s lorries and the ruts were now full of water. It was a dismal sight. The men sank to their ankles as they struggled to reach their allotted quarters. And when they reached them, as often as not, they found rain pouring through the roof.

The Officers’ Quarters were more accessible as duckboards had been laid along the huts. Each of us had a room to himself. Mine was not all that waterproof; it amused me to watch a floor rug that I had being lifted off the floor as the wind came rustling in through the cracks between the floorboards. In my broken-backed camp bed I found I needed as much clothing below me as above me if I was to keep warm.

When we had settled in and the roofs of the huts had stopped leaking and the ground had dried up and we had made paths here and there, the place assumed a pleasant enough appearance. Most of the Curragh is a wide open plain with no trees or hedges to break the force of the wind, but just behind our part of the camp there was an extensive area covered with clumps of furze bushes, hence the name ‘French Furze’, and in between the clumps, patches of grass, completely sheltered from the wind. It was my delight to select one of these for my afternoon’s work, which generally consisted of lectures to my platoon, from the Handbook of Infantry Training. And if sometimes some of my class slept, I’m afraid that didn’t worry me overmuch.

Life now began to be a bit more pleasant. We, the newly recruited officers, began to take more notice of each other. The feeling of tenseness engendered by the presence of our seniors was a thing of the past and we were able to relax, to feel at home. Now, too, we became more pally and began to form friendships. Nathan McGavin became my particular pal. He hailed from Glasgow, and I being of Scottish descent, we had something in common and took to each other from the start. During our stay at the Curragh he brought his sister Nan over on a visit and I brought the two of them to see my Uncle Charlie at Athy. He was a Scot of Scots and fell for the McGavins like several tons of bricks. I also took them to Knocknagee to meet my cousin Madge and her husband George. Later on, when Nathan and I were abroad, Nan paid Madge a visit a couple of times. Nan and I became friendly and kept up a correspondence till she took up an appointment as House Surgeon in a hospital in New York early in 1917, when we dropped it.