14,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

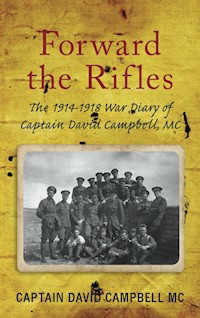

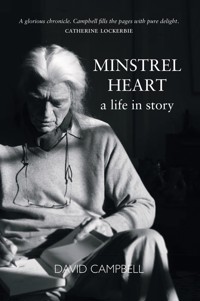

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Guruji said: 'Sing not the song that others have sung. Sing only what you yourself have realised in your own heart.' What I've realised in my own heart is that its song is for many, that it sings for whom it meets on its way. It does not remain at home, but is a wandering minstrel heart. This book is the engaging and colourful memoir of celebrated Scottish storyteller David Campbell. It is an exploration of the nature of love in its many guises, and of David's lifelong love of story. Join David as he tells his story from childhood in wartime Fraserburgh to a holiday job with a dramatic and life-changing conclusion, through a pivotal role as a BBC radio producer at the time of the Scottish renaissance of writing, drama and folk traditions, and finally to his international career as an acclaimed storyteller, mentored by celebrated tinker-traveller Duncan Williamson. The roots of things in my life have always been the love of words, stories, poetry and people, and the joy of bringing them together; it is there that I find the deepest meaning and the sweetest music.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 512

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

DAVID CAMPBELL has been a lover of stories, poetry and people from an early age. These passions have directed the course of his life into teaching, broadcasting, writing, performing and storytelling. Born in Edinburgh, he spent his childhood in the story-and song-rich North-East of Scotland. After graduating with Honours in English from the University of Edinburgh, he worked as a producer with BBC Radio Scotland for many years devising, scripting and directing a wide variety of radio programmes. Mentored in storytelling by Duncan Williamson, David has gone on to mentor many others in the craft. One of Scotland’s finest storytellers, he has toured worldwide with his repertoire of talks and stories and currently lives in Edinburgh.

By the same author:

Tales to Tell I, Saint Andrew Press, 1986

Tales to Tell II, Saint Andrew Press, 1994

The Three Donalds, Scottish Children’s Press, 1996

Out of the Mouth of the Morning, Luath Press, 2009

A Traveller in Two Worlds Vol I, Luath Press, 2011

A Traveller in Two Worlds Vol II, Luath Press, 2012

First published 2021

ISBN: 978-1-910022-66-5

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 11 point Sabon

by Main Point Books, Edinburgh

© David Campbell, 2021

Contents

A Man

Preface by Tom Pow

Prelude

1 A Charmed Life

2 Little by Little

3 Across the Border and Back Again

4 Granny Howling

5 A Windy Boy and a Bit

6 A Boyhood Fantasy

7 To Be Young Was Very Heaven

8 Varsity Meetings and Matings

9 The Tin Room

10 Highland Frolics

11 The Tug of Curiosity

12 Laying a Ghost to Rest

13 A Kindling Spirit

14 We Ran Our Heedless Ways

15 Into the Dark

16 Paradise Lost

17 Musical Chairs

18 The Course of True Love Never Did Run Smooth

19 The Heretics

20 Tinker and Saint: George Mackay Brown

21 In Chase of Beauty: Sorley MacLean

22 The Beginning of a New Song: Iain Crichton Smith

23 In Search of Simplicity: Norman MacCaig

24 Embro to the Ploy: Robert Garioch

25 A New Buzz

26 The Society

27 A Ceilidh Decade: Dundas Street in the 1980s

28 Passionfruit and Pangkor Island

29 Eurydice

30 Bert

31 Camphill

32 In the Listening Place

33 More New Worlds

34 A Torn Land

35 On a Quest

36 A Land in Transition

37 In the Footsteps of Robert Service

38 An Independent People

39 A Lucky Break

40 Elegies

41 A Fateful Day

42 Girl Friday and Robinson

43 West Coast Retreat

The Sweetest Music

Thank Yous: A Fairy Story

Copyrights and Permissions

For my brother John

A Man

A man held out a promise

that he could not keep:

A promise, hope, illusion that he held,

a dream that love could compass all.

But his defeat was that it was,

as once his father said, so long, so long ago,

that he was ‘in love with love’.

And he pursued it all along the decades of his life,

Tore off deception as a layer

of love’s onion skin

And married truth

thinking this was the golden ring,

But found truth

was too stern an inquisitor at many fleshes

For it needed wisdom and compassion

to find half an ounce of worth,

And these were weighty companions,

not easy to fall in love with

But to be earned by patience and humility.

So on he trudged, the boy in love with love,

And every meeting was a joy,

and pain,

Not one without the other.

So, he came to know, as age came on

That all he’d found was still,

as a rough stone on the shore,

In need of tides of time

To smooth it into something beautiful.

(David Campbell, 2010)

Preface

A SURPRISING OMISSION from David Campbell’s memoir is any mention of his hair. When he was my English teacher in 1966, he wore it short at the back and sides and with a long, falling quiff. It was gingerish then, as I recall and, when he returned work to us, he swept his hand back through it, before he delivered a comment. It was a micro-performance from a handsome man, fine featured and with the strong body of an athlete, a good centre I would have thought if he had been a rugby player. He has remained a handsome man – even into his 80s. The pony tail he has worn during the ‘storytelling years’ is now white, but his delight in the moment and an awareness of how it might be best shared have been constants from those flop-haired times.

A ‘performance’ of course presupposes an audience and the memoir shows how David found his at an early age among his playmates, while he in turn was drawn to elders who could tell a story or a joke. Now he can look back and share the moments – the texture of a tale – the future storyteller instinctively saved. Of course, the performer is helped immeasurably by the extent to which he or she has ‘charm’. Minstrel Heart tells the story of someone who I have witnessed charm audiences of school students, university students, family, friends and folk with whom he just happens to be sharing space. Some readers may question his assertion that he has pursued, through his many relationships, an understanding of the nature of love. However, I think of Edwin Morgan’s late collection, Love and a Life, in which long term relationships and the briefest encounters are alike viewed by the poet as manifestations of love.

Lest ‘performance’ sound too egocentric, it has to be balanced – even for an audience of one – with a sense of welcome. As a storyteller, David saw how, with Duncan Williamson and other Travellers he came to know well, this quality is bred in the bone; Minstrel Heart shows the extent to which David himself has always welcomed people into his life and into his flat. Whether they were needy, in want of encouragement, or merely passing, they were welcome to the ceilidh. There is then a depth to his charm; the minstrel heart may have wandered, but it has always been capacious. In fact, a defining feature of the poems which thread through Minstrel Heart is their welcoming tone, the desire to invite the reader to share a memory of a moment or of a person.

One of the attractions of the memoir is its buoyant sense of forward propulsion. (‘Every age has its compensations,’ he once told me.) Blessed with confidence from a young age, David has trusted his inner voice to make the decisions that have shaped his life – and to defend what is important to him. Discarding what no longer held him, thrusting himself towards fresh experiences and new people, we can see how the life ‘understood backwards’ has resulted in a coherence which his blind choices could not have foreseen. His memoir is, as we would expect from a storyteller, an engaging tale; the story of a richly satisfying life. What makes it of greater value, as a historical and cultural document, is what it says about the times it was lived though: most especially, Scotland in the last 50 years. Through inclination, choice and chance, David has been a central figure in the cultural and political shifts that have seen Scotland’s identity move decisively from a British/Scottish accent to a Scottish/British one in which the British element is more and more diminished.

His interests in folk song, poetry and drama, at a time when there was a sense of rediscovery of Scotland’s past and present contribution to each, swept him up in Hamish Henderson’s ‘carrying stream’ of song, story, music and dance. Minstrel Heart vividly gives us a portrait of the excitement of the young teacher whose active interest in drama led to a BBC posting which brought him into contact with Scotland’s foremost writers, among them Norman MacCaig, Iain Crichton Smith and George Mackay Brown; whose interest in live events led to his involvement in intimate and large scale readings; whose interest in Scots and Gaelic culture deepened into the appreciation and practice of storytelling, which has absorbed him, as practitioner, teacher and writer, over the last 30 years.

In Minstrel Heart, you will read portraits of many of the significant figures in oral and print literature over the last half century. I began this preface with my own brief portrait of the poet/storyteller as a young man. Alastair Reid told how, when his prose pleased Mr Shawn, the legendary editor of The New Yorker, it caused a spot of joy to blush on Shawn’s cheek. I once wanted to see something similar in Mr Campbell’s comments, after he swept his hair from his face. It seems so unlikely therefore that I am writing this about him in my 70th year. Yet, from what better point to observe that Minstrel Heart is testament to the many lives he has enriched along his way. I consider it most fortunate that mine has been one of them.

Tom Pow, May 2021

Prelude

Memory

One had a lovely face

And two or three had charm

But charm and face were in vain

For the mountain grass

Cannot but keep the form

Where the mountain hare has lain.

THIS WB YEATS’ poem expresses for me how place and date and detail fade like a ‘glimmering girl’ ‘into the brightening air’, but the emotions remain like the hare’s indentation in the soft grass.

When I reflect over the eight decades of my life, I can see from my earliest years a boy in love with words and with stories, with poetry, with people – loves which were to connect me with singers, poets, writers, actors; with writing and performing myself. I recall in my early teens overhearing my father saying to my mother, ‘Our David is in love with love.’

Sing not the song that others have sung. Sing only what you

yourself have realised in your own heart. (Guruji)

What I’ve realised in my own heart is that its song is for many, that it sings for whom it meets on its way. It does not remain at home, but is a wandering minstrel heart.

I started falling in love when I was at Fraserburgh Primary School, aged five. I was in love simultaneously with three girls in my class. No one knew except myself. They were Nadine Soutar, Vivien Stafford and Norma Bissett. Nadine’s face was soft and pear-shaped. I suppose she became June Allyson, the film star of my adolescent infatuation. Vivien was definitely Rita Hayworth, and Norma a sultry Gina Lollobrigida. I had no difficulty in adoring each of them equally and separately.

This ‘falling in love’, being inexplicably drawn to someone, has been a constant in my life, as has the tendency to be in love with more than one person at a time. In my mature years it has evolved into the conviction that we are married to the person, or persons, that we are with at the present moment. Right now, it is to myself as I make this entry into my life stories.

This seemingly inborn, karmic, or whatever, tendency was to become the source of great loves, pleasures, vexations and complexity, as well as a pilgrimage in search of understanding my own nature, and the nature of love itself.

David Campbell, Edinburgh, May 2021

1

A Charmed Life

WHEN I WAS a baby, our family lived in a house in Craigleith Hill Avenue in Edinburgh. I slept in a cot adjacent to the room of my mother and father.

One day when my father returned from his work in the then labour exchange, my mother insisted, ‘We have to move David into our bedroom.’ There was no apparent reason for this except my mother’s intuition and adamant insistence, but my cot was moved into their bedroom.

That night the ceiling came down in my room. Lumps of heavy sodden plaster fell directly where I had been lying.

2

Little by Little

HOW COULD I know how big the world was? Why would I need to know? It was simple. I had a big brother and a big sister, a wee brother, an old comfortable granny and a mum who made breakfast every morning, except Sundays when Dad brought everyone breakfast in bed. This was the world. Our house was white and had a garden. These houses, built in the ’30s, occupied only one side of the street since we were so far on the outskirts of Edinburgh that we still had a farmer’s field in front of the house and the playground of a disused sand quarry at the back. It was a cosy cradle of childhood, nourished by bedtime stories my dad told my wee brother but that I eagerly eavesdropped to hear. They were always about a boy adventurer called Johnny Morey who travelled the world.

I remember how I loved my sister’s tortoise. He was a small explorer. I can see him still, brown and pondering on the green back lawn. He lived under a hard smooth shell; the shell seemed to be made of pieces glued together, brown as chestnuts. This tortoise sometimes poked his head from under his shell house. His neck was as long as my three-year-old middle finger, but dry and crackly as if it would creak when it came out of the shell. But it didn’t; it was completely quiet. Sometimes he would go for a walk across the lawn on his four padded feet. He was very, very slow. I called him Little by Little and loved watching him moving always as if he knew where he was going. I was very fond of Little by Little. He was my friend.

One day Little by Little seemed especially clear about where he was going and I watched a long time as he made his way out of the garden gate into the field across the road. The field was vast, full of sun-ripe tawny barley, and into that vastness Little by Little made his way watched by my affectionate eye.

When my sister enquired where he was, I innocently replied – so I am told – ‘Oh, he went for a walk.’ This, a preface to sister’s horror and tears when she discovered where he’d taken his walk.

The family, except Granny, searched the field for what seemed ageless hours until dark fell and the harvest moon rose. That talismanic tortoise still visits me, his lone and fearless journeying to adventure, freedom and danger.

Like my father’s Johnny Morey and the tortoise, I was from my earliest days an explorer. I was an explorer because I knew that always I could return to that cossetting cradle, unlike my friend the tortoise. Even aged three, the toddler me would stray along the road to the neighbours, some 300 yards away, who would phone my mother to say, ‘Mrs Campbell, don’t worry about David, he’s visiting us.’

3

Across the Border and Back Again

IT WAS OUT of this cosy world that my father’s temporary position in the Civil Service drew our family to the village of Sprotbrough in Yorkshire, a difficult and alien world for five-year-old me. A photo of my face and posture eloquently expresses an anxious, fraught child. Not only was the language at first unintelligible, but as a stranger I was harried and ran from the school gates, first to the brief sanctuary of my father’s office and then, the coast clear, home.

Two memories of Sprotbrough indicate an early sense of empathy. One day brother John, in helping to clean the brasses in the house, had inserted his finger into the tin to gather some scrapings. In no way could he extract it. This filled me with tears and inconsolable alarm as I had visions of a lost finger or a brother with a Brasso tin appended to his hand forever. Huge relief when it was removed, I don’t recall how.

My mother did not like living in England and longed to be back in Scotland, and so with my little brother she returned to stay temporarily with her mother in Pitlochry. During this time, my father took me to a circus. I still recall my eyes streaming with tears. The ring master smartly dressed in red tunic and white trousers sacked a little clown for some misdemeanour. As the little disconsolate figure in floppy jacket and baggy trousers was walking away, stooped and sad, the ringmaster called him back,

‘Hey, where did you get that jacket?’

‘From the circus,’ said the clown, taking it off and handing it to the ring master.

‘The shirt?’

And so on it went until the little fellow trooped out and away wearing only loose floppy underpants, leaving my father to put his arm around me, dry my flooding tears and explain that he was not really sacked but would be back for the next show.

My childhood propensity and desire to entertain and do tricks found an exemplar in a cheery, rotund, eeh by gum, Yorkshire friend of my father, Sam Leadbetter, who intrigued me with his bowler hat trick. He would put on the hat, stick his middle finger in his mouth, puff his rubicund cheeks and strenuously blow, and lo the hat would tip up from his head. Magic! Despite my huffing and puffing till red in the face, my efforts were in vain until he revealed the secret. He stood back to the wall, and the brim being firm, leaned gently back simultaneously with the blowing and elevated the hat!

It is interesting how early these personality characteristics manifested themselves and how different the nature of siblings. Neither my little brother nor my sister had any desire to entertain, and brother John was a talented but modest pianist playing for pleasure, and not an entertainer like me!

It was also at this time that my love of words was ignited. I briefly had a marvellous teacher who introduced poetry by reading it and encouraging us to listen. A poem that moved me deeply with a sense of compassion and joy was ‘Abou Ben Adhem’:

Abou Ben Adhem

Abou Ben Adhem (may his tribe increase!)

Awoke one night from a deep dream of peace,

And saw, within the moonlight in his room,

Making it rich, and like a lily in bloom,

An angel writing in a book of gold:–

Exceeding peace had made Ben Adhem bold,

And to the presence in the room he said,

‘What writest thou?’ – The vision raised its head,

And with a look made of all sweet accord,

Answered, ‘The names of those who love the Lord.’

‘And is mine one? Said Abou. ‘Nay, not so,’

Replied the angel. Abou spoke more low,

But cheerily still; and said, ‘I pray thee, then,

Write me as one that loves his fellow men.’

The angel wrote, and vanished. The next night

It came again with a great wakening light,

And showed the names whom love of God had blest,

And lo! Ben Adhem’s name led all the rest.

Leigh Hunt

I include this poem since its sentiments went so deep at that age; I learned it and still recall it.

My father’s application for a transfer back to Scotland had him posted as manager of the local labour exchange in Fraserburgh, where amongst his other duties was the placing of evacuees from the war.

In Yorkshire, my mother had vigorously made clear my adoption of the local dialect was certainly not for home use, and when I arrived in Fraserburgh aged five, I rapidly had to learn Doric, that highly distinctive North East dialect so different that not even Lowland Scots can understand it. But I can still fall into it with a fluent and congenial ease like meeting a long-lost friend. This language too had to be abandoned as soon as I crossed the doorstep into our house.

Learning the language was not the only challenge. In Primary One Fraserburgh Infant School, I was rapidly acquainted with the fact that on the next Friday I was to fight the class champion, Charlie MacDonald, a sturdy, well set up, local fisherman’s son! Luckily my big brother John was home on leave from the RAF and took it upon himself to give me boxing lessons, and the advice to attack rather than defend.

On that Friday, a circle surrounded Charlie MacDonald and me with cheering encouragement for Charlie from classmates. He seemed formidable but five-year-olds are not capable in fisticuffs of inflicting serious damage. Anyhow, by luck or by John’s advice, I landed a blow on Charlie’s nose which gushed with blood, the sight and realisation of which brought tears to the champion’s eyes concluding the combat with me as victor and new class champion. The threat however remained of the ‘best of three’. Fortunately, that was never realised.

Inside the classroom things were peaceful. We had a beautiful young Polish teacher called Miss Petroshelka. One day, reluctantly I suppose, she took me out from my seat at the back of the class to be belted for talking. It was then a universally accepted part of school life that this was the punishment for misdemeanours: to be strapped on the held-out hand by a leather belt.

I returned to my seat and continued talking – perhaps in part a result of the leniency of Miss Petroshelka in delivering the strokes. Asked why I still continued to talk, I apparently replied, ‘I hadn’t finished what I was saying, Miss.’

This charm and leniency did not prevail in the Central School, to which we graduated aged seven. Our Primary Three teacher was to be the grisly Miss Cranner. In today’s teaching world, she would not have survived – one of her habits was to hurl the leather belt across the room at miscreants. How she failed to injure or escape censure is a mystery.

My younger brother and I were too young to appreciate the dangers of frequent German bombing raids on the targets of VASS’s munitions factory, Maconochie’s food tinning factory or the prosperous and important fishing fleet. During the raids, my mother turned the sofa upside down and put my little brother Eric and I under it until the long shrill blast of the all-clear. My brother’s red and black Pinocchio-like gas mask seemed more fun than my standard black pig-snouted model.

Because of the importance of the fishing, the crews had extra rations so as a bonus we had plenty meat and endless supplies of fish from the seaport. On our Sunday walks with my father, farmers would supply him with fresh-laid eggs. At a time of severe rationing, we were never short of food. At the top of our road was an anti-aircraft gun site where we kids visited and the soldiers gave us chocolates.

We children were happy, unafraid and unconscious in any deep way of the perils around us. The presence of the war was a daily reality. When our mother took us down to the harbour, we’d see the herring girls with their lightning fingers at the quayside gutting the fish and throwing their innards into the air where the swooping, shrieking gulls would snatch and gobble them before they neared the ground. On Sundays, the harbour was thronged with little fishing trawlers in bright primary colours bearing mysterious women’s names, and smelling of tarry rope and fish, but above them floated huge barrage balloons to protect the little boats from enemy dive bombers.

In wartime Fraserburgh, life for a child growing up was wonderful. There was space and freedom – space and freedom except on Sundays when we could watch the families in black, like big crows followed by docile little crows, making their doleful way to church. None of our family attended church. My father, who had seen a woman’s name struck from their family Bible because she had conceived out of wedlock, vowed at an early age he would never attend a church which could do such a thing. Hence, we didn’t go to Sunday School or church. My mother’s sole stated religion amounted to the wise dictum, which she exemplified, ‘Do as you would be done by.’

The swings in the playground were chained, like the local children, into silent obedience to the Lord’s Day of rest, but my father took my brother and me on wonderful walks along the sand dunes, and one of the longest and most beautiful beaches in Scotland. We were also warned not to go near the big awesome pronged enemy mines beached on the shore that could blow us to smithereens, wherever that was! We also walked the lighthouse wall breathtakingly exposed to the wild waves and dramatic sea sprays.

An occasion which wakened delight in me was a family visit to Aikie Fair. At this fair was a stall in which you rolled a penny down a little chute and it had to land centrally on coloured squares with numbers or blanks on them. My penny landed on the unthinkable riches of a ten shilling note! I was wealthy beyond dreams.

But I was wakened to a wealth of the heart in a tent where a dark-eyed, black-haired tinker woman stood still and solid and singing. The ballad she sang was ‘Son David’. her name, Jeannie Robertson. I was mesmerised. The rest of my family were completely unmoved by her voice, and oblivious to the electric effect it had had on me. Something was kindled. I love that ballad. It was a foretaste of the great Traveller singer-storytellers I was to admire, meet and become friends with later – Lizzie Higgins, Sheila Stewart, Stanley Robertson, Duncan Williamson, folk who were to take me into the treasury of their tradition, lore and ways of thinking. Duncan Williamson was to become a friend, teacher, companion, pain and inspiration and part of my life for 20 years.

4

Granny Howling

MY FAMILY, LIKE countless others, was scarred by the sufferings of two World Wars, the deaths and wounds, the legacy of grief and psychological trauma.

When my brother John was 18, he was a Flight Engineer in the RAF. My sister, Anne, 17, was working in the office of the munitions factory. My father, too old for a call-up, had been transferred to Fraserburgh as manager of the local employment exchange. He was also in the ARP, the Air Raid Precautions service. He returned from one of the frequent night bombing raids to tell us of a wall blown clean off a house, leaving a bed miraculously suspended on high by its two bottom legs – an old woman perched on the headboard. She refused to be rescued without the mattress. Sewn into it were her life’s savings.

At the time, my mother kept open house for the British, Commonwealth and Polish air crews stationed for training at nearby Cairnbulg Air Base, so our home was always abuzz with what seemed to us kids giant laughing men in uniforms, men who were in or hardly out of their teens. Two young Australian airmen who were both fond of my sister Anne, then 18, were to feature in a surprising way 50 years later.

I remember aged seven being in high excitement because I was allowed to go along the road myself to the station to meet my big brother who was coming home on leave. Intent on meeting him, I didn’t recognise him in his uniform and hurried past. He called me back,

‘Hey, DD, where are you going?’

‘I thought you were a big air man,’ I said.

‘I am,’ he replied, ‘I’m a Sergeant now.’

John loved his kid brothers and used to play with us and sing current War chants like ‘Hitler, boy, what a funny little man you are’. When he was stationed close by my mother’s sister in Rickmansworth, near London, he could take short leaves. From there he sent my mother a letter:

I’ve never been able to do much for you. Let me pay your fare and the boys’ to London and you can come down for a while.

My mother was certain he had a premonition of his death. My mother and I and little brother, Eric, took the train there for a visit. My granny was staying there at the time.

It seems that the moment he died, my mother was walking down the stairs at my aunt Nan’s house, and said, ‘Something has happened to John.’

It was the morning of 21 July 1943. I woke up in my aunt’s house to the sound of my grandmother’s wailing, and when I came from my bedroom, saw her twirling her thumbs, pacing to and fro, wringing her hands. My mother was pale and silent. She once told me that John had loved her more than any other human being ever had, and to me this seemed reciprocated.

His plane, a Stirling Bomber, had crashed in England killing the crew. His funeral was in a church in Rickmansworth. In the chapel, I saw his coffin, shining polished wood with glittering brass handles. I wanted to see him, but somehow I can’t remember how, I gathered that he was too broken for me to see. This baffled me – I imagined him lying there in his smart RAF uniform but his face unrecognisable. To the drowning sound of the organ, we sang ‘Eternal Father Strong to Save,’ his favourite hymn.

The shock of John’s death killed the child my mother was carrying. We would have had another wee brother. In a way, I think my mother never recovered. The love between her and her firstborn was deep and intense and full of fun, as I found when I came across a letter he wrote to her shortly before his death. Every year until she died aged 94, I could feel the tacit pall of grief when I visited her on 20 July. In 1981, when I visited my mother at her home on Armistice Day, I saw lying under the photograph of John wearing his uniform, his 19-year-old face and clear eyes, a poppy; I found it hard to keep back tears.

My father was equally devastated by the death of his stepson John whom he loved fully as much as he did Eric and myself. He arranged a family holiday on a farm called Balnealach, Perthshire, by way of helping the recovery I suppose. By now, the nearby woods were ready for the hazelnuts to be gathered and so he took myself and my brother hazelnut gathering.

Late one afternoon, now aged eight, I went to this hazelnut wood alone and there sat beneath the trees in dappled sunshine and wept inconsolably for the death of my big brother. When I returned to the farmhouse, my family – mother, father and brother – were already sitting to eat supper. Although nothing was said, I think they sensed from my silence and the red eyes something of my sadness, and I was grateful to be allowed that privacy. Years later, and still now, the words of Dylan Thomas speak to me:

After the first death there is no other.

By now, my father, my mother, my sister and younger brother have all died and I recall these deaths with equanimity, but I’m still brought to involuntary tears when I remember or tell anyone of the death of my big brother John. And in my memory, I always recall that hazel wood where my eight-year-old self grieved alone and privately. The first two lines of WB Yeats’s poem ‘The Song of Wandering Aengus’ resonate with that childhood memory:

I went out to the hazel wood

Because a fire was in my head.

I always associate this poem with its enchanted sense of another world, invisible but a mere glimpse away, with that childhood experience in the woods, that private last farewell. This sense of privacy of grief has made me avoid participating in communal ceremonies of grief, and uniforms and militarism became anathema to me. Aged 12, at George Heriot’s School, I resisted every overture to join the Combined Cadet Force. My conviction was confirmed when I heard the raucous, saw-edged bullying schoolboy Sergeant bawling at young recruits. It didn’t help that my incompetent Maths teacher was in charge of these recruits. There were rumours too of queer goings-on in the tent on CCF summer camps.

On Armistice Day when I was 12, in my first year at George Heriot’s School, all the staff and boys were gathered before the Cenotaph for a service commemorating the dead former pupils of two World Wars. All the cadets and staff in charge of them were in uniform. All the boys who had lost a father or brother were expected to form a line in the front row.

I hid, even at that age being horrified at the idea of being drawn into a uniform lament when my own sadness about the loss of my brother and all that it meant was totally private. This sense I shared with my mother who never made any public show of the deep and devastating grief of the loss of her first son. The only thing she made clear was that she wished the casket of his ashes to be scattered along with her own when the time came. When the time did come, my brother and I threw them both to the wind on top of the Braid Hills in Edinburgh where my mother and brother John had walked.

Ashes

April fourth 1994

you died mother.

After the cremation

I phoned the undertaker

to ask for your ashes.

The undertaker lady told me they were safe

in a plastic bag

not a casket.

I thought you might smile at that.

Under my bed lies a casket.

It contains the ashes of your son, John,

killed on his twentieth birthday.

The clumsy bomber he was engineer of

bursting into the ground.

You wished these ashes of fifty years

to be scattered with yours;

We will find a place for such a wedding.

Confetti of ashes,

and each flake will be our gratitude for you

and the grown seeds

you left to follow you

into the dust.

With her family’s experience of the sufferings and traumas of two World Wars, in which Germany was the enemy, it was understandable that my mother had an extreme dislike of Germans, a dislike confirmed by the horror stories of the Concentration Camps. Yet the effect on me in my 20s was signally different.

5

A Windy Boy and a Bit

Now as I was young and easy under the apple boughs

About the lilting house and happy as the grass was green,

The night above the dingle starry,

Time let me hail and climb

Golden in the heydays of his eyes…

(‘Fern Hill’ Dylan Thomas)

TWO YEARS AFTER the end of World War II, my family returned to Edinburgh. Before finding a place to rent, we stayed at the house of my mother’s sister, Aunt Nan, at 29 Pentland View, where I’d lived for the first four years of my life. My father had sold it to her at a knock-down price – providence in money matters not being one of his qualities – and so my mother, father, myself and brother were now living with my aunt and two cousins. The house had three bedrooms, a lounge and dining room. The lounge was now converted into a bedroom for my mother and father, and somehow this temporary arrangement passed congenially.

A playground paradise in the form of an extensive disused quarry was at the back of the house. No advanced thinking adventure playground designer could have planned a better environment for fertile adolescent imagination and physical activities, endless ingenious games, physical challenges and creative enterprises.

At the top of the main road was a row of shops. The quarry extended from there for a quarter of a mile in one direction and was probably 300 yards across. This wonder world contained many hillocks, one precipitous incline, a stream, a small pond (sometimes frozen), a turret hill that had contained a wartime shelter, many banks, trees, elderberries and rhubarb growing wild, and a forest of hemlock. The dried stalks of these lofty plants made ideal spears and makeshift javelins.

29 Pentland View was the first house in the row, there being 200 yards of unbuilt land between it and the main road. On part of this was a section of the old farm road by the side of which grew a sturdy mountain ash which we christened ‘the aeroplane tree’. There we each had our appointed perch, and this was the place to plot, plan and devise our enterprises. There we’d climb and talk – my gang. This was the very tree where on one occasion my cousin Alex, two years older than me, climbed to a branch above. This branch broke, tumbling Alex on top of me, and me to the ground where I broke my wrist.

The core members of my gang were myself, my brother Eric, neighbours Ali and Tubby, and we also had a tomboy, Anne, whom we admired for her pluck and readiness for everything. I’d be 12 when the gang was formed, my brother nine, Anne and Tubby 11.

Later, further members were enlisted and we amalgamated with another gang. The raison d’être of our gang was not the usual activities associated with the word ‘gang’, but more akin to the gang of ‘outlaws’ in Richmal Crompton’s Just William books. We devised and built a variety of huts, held Olympic Games, produced plays, invented a Quarry Broadcasting system and cooked over campfires.

Perhaps it was the imminent coming of the Olympic Games to London that in 1948 made me decide that the gang should hold the Quarry Olympic Games. These were customised to our equipment and surroundings, as well as to the individual abilities of the gang members. In the flat space between the old farm road and 29 Pentland View were two shallow sandpits, the one ideal for long jump and hop step and jump, the other for high jump and pole vault. The vault was dangerously executed at first by using a clothes pole! Later we discovered bamboo. We also invented a springboard jump. This consisted of creating a springboard from a thin plank and a box. The contestant would sprint up to the springboard and leap airborne, it seemed to me, to dizzy heights of six feet and over.

Each gang member had for each event his best performance assiduously noted. We improvised our own hurdles and stone shot put. Our gang had a marathon emulation in a race to Hillend Park and back, about five miles, for which my brother Eric had the inbuilt stamina to win. We had also cycle races of that distance in which I didn’t participate since I had concluded that cycling developed the wrong muscles. And I didn’t have a bike.

From the individual ‘record’ performances, I calculated handicaps and when I look back it was a measure of my inbuilt desire to encourage that, although I was the best athlete, I never won the Olympic Games, nor was the all-over champion.

By the second year of this great enterprise, we had gathered the ‘Springers’, the kids from Comiston Springs Avenue. One of these, Gordon, was neither a good runner, jumper or thrower, but he was the clear champion in two of our unique events. In the ‘hanging on to a branch by hands for the longest period’, he could easily outlast any of us. We also had a crazy endurance event. Tubby, our precocious scientist, had invented an electric shock machine activated by turning a handle. Gordon seemingly could endure endless amounts of electric current, again for periods far exceeding any of us. Gold for stamina and endurance in each of these events.

Another scientific contribution of Tubby’s presaged an important phase of my future. In a farther-from-houses part of the quarry was a little hill. Out of that hill we dug an earth hut covered not with corrugated iron but, inauspiciously, with corrugated asbestos sheeting, which in turn was covered with turf, and the gang of four or five could enter from the door dug in the side and sit there cosily. Tubby rigged a microphone some 50 or 60 yards away in a glade where, by a fire, I sat of an evening and told stories, mostly mystery or ghost. These, by the wonder of Tubby’s knowledge, were relayed to speakers in the hut on the QBC, Quarry Broadcasting Corporation. I remember especially putting the chill of fear into both myself and my audience by telling a story I had found. It concerned a Dr Morris, a sinister doctor-hypnotist who experimented with his patients by exploring the threshold of pain under the hypnosis. Meantime we had cooked rhubarb with purloined sugar!

This hut collapsed because of the unsuitable brittleness of asbestos as roofing, not known then to be a health hazard, but probably a fortuitous collapse. The hut was soon replaced by a well-built structure of wood stakes with corrugated iron nailed on: an ideal den.

My popularity as a gang leader was seriously dented when I fell in with slim, beautiful, fair-haired and pigtailed Izzy, or more romantically ‘Isobel’ in my early love-struck attempts at verse. This distraction and her incorporation into the gang did not at first go well. Izzy was lean, confident, and right! I was stricken, blind, and delighted. She was less than enthusiastic about the Olympics, although swift and adept enough in the chasing games and the ‘hido’ – hiding illicitly in the stooks of the corn field where I had carelessly lost my sister’s pet tortoise, Little by Little, as a three-year-old.

What devotion, what sweet innocence and what romantic notions infused my love for Izzy, the guileless poetry and dizzy daydreams; I was a musketeer who’d rescue her from desperate perils. Heroic fantasies! The reality was somewhat different and the passion was expressed by no more than holding her hand as I walked her home sharing glucose tablets, which I imagined improved my athletic prowess.

And then came a moment of enlightenment. Izzy and I were alone in the quarry and we decided to make a fire. We were aged 13. I said I would make the fire.

‘No,’ said Izzy, ‘I’ll make the fire. We learned how to make fires at Girl Guides.’

‘I know how to make them. I make them all the time,’ I countered.

‘Well,’ said she, ‘we’ll make two fires and see whose is best. Three matches each!’ She stood a slim figure of complete assurance.

Two then it was.

We gathered our kindling, twigs and wood, and were ready, mine built by experience, hers by the Girl Guide book!

My fire was soon aflame; hers, despite the three matches, remained dead.

‘So,’ I said, ‘mine’s best.’

‘No,’ said she, ‘mine is the proper way to make a fire. It’s the best way!’

I was completely baffled by this confident alien logic, a bewildering psychology. There she stood, a lean figure of certainty by the dead fire. Rendered totally incapable of words as I looked at her, so complete and dauntless and wrong, that in my bafflement I aimed at her a brief clumsy kiss, so that we stood back from one another in astonishment. However ineptly, we had crossed a threshold: our first kiss. We roasted two potatoes on the fire.

By the time I was 14, I decided that I would learn to dance, take ballroom dance lessons. I suppose this was at least partly inspired by the realisation that there would be girls in the class, and somewhat influenced by the debonair grace of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. This decision was to have many consequences. Another impetus was that by that age I was a member of George Heriot’s athletics team and, as such, could attend the school annual dance, and take a partner!

Diary entry, 8 December 1950: I met Isobel in the tram and went to her house and I asked her, with her mother’s permission, to the school dance. She accepted.

20 December 1950: Isobel and I went to the school dance – in evening dress. Super! Overstayed our time but got a taxi home at 12.30am. The evening was bliss. I gave her a pound box of chocolates.

The dance class I attended was run by a remarkable woman, Doris Cowie. She was at that time in her 30s, red-haired, slim, energetic and punctilious. She was full of fun, married to John, an amiable accountant, far too fond of drink. They had a fair-haired daughter of nine years called Shirley. In that small dance class of six pupils, I was at first the only boy. These five girls were pals and paid me little attention, but I was learning the waltz, quickstep, slow foxtrot, tango! I loved it and subsequently not only did I progress from bronze to gold but, easily persuaded by Doris, I took the qualification as a teacher in ballroom, Latin American dancing. With this qualification I became Doris’s assistant and in these days of thriving ballroom dancing I thereby earned considerable pocket money whilst I was at Edinburgh University.

Meantime, I had started my education at George Heriot’s School. My brother John had been a pupil there. This school had been founded in 1620 by Heriot who was money lender and jeweller to King James VI and I. His legacy and will was still maintained in that the school had so-called ‘Foundationers’ so that the children of single parents would be educated free of charge.

My mother was determined that her children should have the best education possible. At that time the fees at Heriot’s were modest, but our family was struggling for money. My father thought, for several reasons, not least his egalitarian socialist principles and in-built thrift, that we should go to the free corporation school. Despite our financial struggle, my mother would have none of it. In such matters she was insistent. Her conviction that the prestige of a ‘good’ school, and my brother John’s having been there, were unanswerable arguments, and so I found myself at Heriot’s. My mother had made a personal appointment with the then Vice-Headmaster, Eddie Hare, who’d known my brother, and lo, I was whisked into Class 1b, for reasons that were not clear. That class had German as a second language. Apparently, this was a time when that language was useful in Science, and Heriot’s had a tradition of producing scientists and doctors from a school timetable heavy with Chemistry, Physics, Zoology and Botany. Learning German, however, was to influence a decision later in my life.

It was inevitably something of a shock to come from a primary school in the small north-east fishing town of Fraserburgh to secondary school in Edinburgh. There was a little bonus. The tram car I took from Fairmilehead passed the stop where Izzy would board – if she wasn’t late. I would keep her a seat in the round upstairs compartment at the front of the tramcar. For these precious morning meetings, I would save up jokes, innocent and doubtless corny, but this was my method of courtship, the beginning of a lifelong addiction to joke telling and, in a way, an apprenticeship for a future career as a storyteller. When I was 14, at Christmas time, I presented Izzy with a poem I had written for her. This romantic liaison became more sporadic when we moved from my aunt’s house and rented a flat in Mardale Crescent. It was there aged 14 that I developed pneumonia.

My crude diary of the time records that my fever was so high, the pain in my back so invasive, that I had no sleep during the night. And on Friday 13 March 1949, I was admitted with an alarmingly high temperature to Edinburgh Royal Infirmary. There, I received penicillin injections and a painful hole was bored in my back. My mother visited to find me at an open window surrounded by several students being examined and addressed on my conditions by the professor. She asked the physician to explain why I was at this open window. He suspected an underlying chronic condition in my lungs.

‘You only need common sense,’ said my mother, ‘to know that you address a critical condition before a chronic one. I want my son to be removed from this window at once.’

I found myself moved to a bed in the middle of the ward.

On 9 April, after nearly a month in hospital, I took farewell of my friendly nurses and some of the patients and was glad to return to my family.

School was to further my interest in words, story and drama in several significant ways. Despite the curriculum bias to Science, there was a thriving school play tradition, a ‘Lit’, Literary and Debating Society, and two compelling English teachers, both of whom I was lucky enough to be taught by.

The most remarkable was ‘Chinkie’ Westwood who derived his nickname from the fact that, as he himself announced to new pupils, ‘Although I know very well how much I resemble an oriental gentleman, I would prefer that you call me “Spats.”’ He habitually wore spats, sported a boater hat and carried a Malacca cane walking stick. His appearance was the least of his uniqueness.

His room was next to the top of the turret staircase in the quadrangle corner of the spectacular 17th century stone school. Its high walls were shelved with books. I remember one day our class trooped in without seeing our unpredictable English teacher and one of us said, ‘Where’s Chinkie?’ From the top of a ladder looking out a book came the answer, ‘Your oriental friend is aloft.’ At that time, we had no feeling that the nickname was derogatory and we certainly had great regard and admiration for our eccentric English teacher. It was long before the age of political correctness.

He taught with what seemed to be the principle of constant surprise. Later in life, when I became a teacher of English myself, I followed this example, realising that when the students couldn’t predict what was coming next they had to stay awake and attentive.

If you happened to be in our oriental friend’s class, mid-morning he would summon a boy to his desk, which was slightly elevated at the front of the class, with a sharp, ‘Ha lad!’ and beckon him to his side, mutter in his ear, and the boy would disappear downstairs. He would return with a tray, tea and biscuits and our unconventional teacher would spread his morning newspaper, drink his tea, and instruct us, ‘Seven minutes free conversation with your neighbour, lads.’ Tea drunk, the lesson would proceed.

He was a wonderful reader and had us, as 17-year-olds, hiding our tears at the tragic conclusion of the poem, ‘Sohrab and Rustum’. He also branded that poem permanently on our minds by once more whispering an injunction to a classmate who vanished while ‘Spats’ startlingly impressed upon us the omnipresence of the Oxus River in the poem. Down the turret stairs came a mini deluge, the cascade carried by the messenger emptying two buckets of water from above. From below a minute or so later came a bewildered History teacher under whose door downstairs some water of the Oxus had seeped!

Another way in which the imaginative ‘Spats’ extended our thinking and capacities to express ourselves was that he would command every boy to propose a five-minute speech without notes on any subject that interested him. I recall regaling the teacher and class with the intricacies and relative effectiveness of different styles of high jumping. I myself, pre-Fosbury Flop days, favouring the Western Roll.

Our English teacher also conducted an after-school ‘General Purposes’ club in a small room adjoining his. In that room he taught shorthand and typing to prepare us as future journalists or writers. This he taught along with knitting, holding that this should not be the preserve of education for girls. He also had in this room a small billiard table!

Very unusually for the time, a black boy, Olu Ogunro, came to Heriot’s whereupon ‘Spats’ made sure he was welcome, announcing to his class,

‘We have a black boy in our class from Africa. His name is Oludotun Ogunro. We will call him Olu for short. To make him welcome we will sing a Scottish song for him, ‘Roaming in the Gloaming’. Ready?’

Everyone sang heartily and laughed loudly, and Olu had instant acceptance; brilliant psychology from an enlightened teacher. Olu incidentally became a high jumper in the athletics team, where I was the captain.

The conclusion of this inspiring teacher’s career was as crass and unenlightened as he was enlightened and wise. He took a small group to Greyfriars Bobby’s pub to expound its history and explain the traditional measures! Crime of crime, boys in a pub. This much-loved and brilliant man was sacked.

One day I met him on The Mound, clad as ever – boater, spats, Malacca walking stick – and he informed me that, amongst other things, he was now studying Theology at New College.

Our extra-curricular education at Heriot’s, apart from the inspired English classes, probably taught and formed me more than the standard timetable. The tradition of debating at the ‘Lit’ was a marvellous nursery for public speaking and thinking on your feet. Even as timid first year pupils, aged 12, on a Friday evening we would be amongst the stars of the Upper School and encouraged to stand up, formally address the Chair and make a bold, if hesitant, contribution to the debate. From this, we progressed to win inter-scholastic debating contests which I later continued at university level.

As well as taking part in school plays, those of us in the echelons of the upper forms devised variety shows, performed for the public in the school hall. For these, we gathered the best singers, musicians and script writers. My fellow creator and producer in this was a close companion at the time, Ian Gloag, always top in English to my second top! He wrote like Raymond Chandler and together we devised comic and satirical sketches. The well-known actor, film and television performer, Roy Kinnear, was cradled here. These activities and my love of poetry presaged my future as an English teacher, radio producer, writer, storyteller and sometime poet.

My sporting career at Heriot’s did not include the iconic rugby. This was by an odd circumstance. When as a 12-year-old I arrived at Heriot’s as a first year pupil, I discovered that after lunch on Wednesday afternoon all my classmates had mysteriously disappeared, and so I took the tramcar home. The same thing happened on the second Wednesday. By the third, I learned that they had gone to a place called Goldenacre to play a mysterious game called rugby. In Fraserburgh, I had never heard of this game.

So it was that I continued with my free Wednesday afternoons, my presence at Goldenacre seemingly not missed. However, I subsequently discovered that my ignorance of this vitally important game relegated me to a sub-species.

One of my English teachers was Charlie Broadwood and one day he said, ‘Hands up all the boys who saw the fps trounce Watsonians at Goldenacre on Saturday.’ There was a healthy show of hands. ‘Now (pause), stand up all the keelies who didn’t.’ Ignorant of what an fp was, who Watsonians were, what a keelie was – although the derisive tone indicated it wasn’t a good thing to be – I rose to join the ranks of inferior beings.

However, I was to be redeemed, though not in Charlie’s opinion.

Having discovered that this Goldenacre was a place for cricket and athletics in the summer term, I took myself there where I found a shed of athletics equipment – high jump stands, javelins, discuses and shot puts. There were also sandpits.

Being devoted to high jumping, for what reason who can tell, I was a sole figure practising on my own, raising the bar incrementally to my best height, and unconsciously, being observed by the new games master appointed by the Head Master, William Dewar.

Donald Hastie, this games master, realised that I was jumping high enough to be included in the under-14 section of the athletics team, and could have won that event in the inter-scholastic championships. He also informed me that I had somehow devised an economic form of jumping called the Eastern Cut-off, with which style an Australian had won the high jump in the 1948 London Olympics with the now modest height of six feet, six inches. That was the beginning of my ‘official’ athletics career, fostered by our homemade Olympics. Donald Hastie had been a pole vault competitor and so became a splendid mentor and coach. It was soon clear, however, that some of the old guard volunteer rugby coaches on the staff resented him, at the least. I loved several events and by my dedicated and tireless practice, excelled in them, and was delighted to be elected by the boys as Captain of the athletics team. This role totally suited that strong part of my own nature as teacher and fosterer of the younger and talented members of our team.

I was twice school games champion and for a while held the school record for high jump, pole vault, and shot put, as well as being Scottish junior pole vault and high jump champion in 1954. Subsequently, I represented the Edinburgh University team as a pole vaulter.

Outside all of this, my greatest teachers were my father and mother.

My father was born in Greenock in 1887. He left school at the age of 12 with a little green pamphlet-sized document called the Scotch Leaving Certificate testifying to his proficiency in Reading, Writing, and Arithmetic. I still have that document. With these qualifications, he became a shipping clerk, starting work at five in the morning. His attempt to enlist for the army in 1914 for World War i was refused because he had flat feet. He belonged to the tradition of those Scots who valued education and read widely, and he became the youngest manager of a branch of the Labour Exchange in Scotland, the early incarnation of the dhss, but without the bleak reputation that organisation has now.

My father was an avowed and idealistic socialist, supporter of the Labour Party. This idealism and the principles of egalitarianism were a persuasive part of my own political education, and from an early age my father taught me how to argue, how to argue persuasively.

I remember I was taking part in a school debate and was putting my arguments to my father. At a certain point, I countered him by saying: ‘Dad, that is absolute rubbish.’ His mild reply was a measure of his wisdom as a teacher. ‘Well, David, you’ll need to find something more persuasive to express that if you want to win your school debate.’

I realise now how aware he was that he was nourishing a young mind. Amongst other gentle lessons I learned from him was the occasion when my granny was staying with us, and she said to 12-year-old me as she prepared for bed,

‘Now David, you’ll not forget to say your prayers.’

‘I don’t believe in God, Granny.’

My father said nothing at the time, but later, ‘David, your granny is an old lady. She has said her prayers all her life. You can discuss your beliefs in God with me or anyone else, but by telling Granny you don’t believe in God, you are just upsetting an old lady.’

My father was deeply interested in spiritualism, and his view of life beyond death could be summed up by Hamlet, ‘There are more things, Horatio, in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy.’

Our family never went to Church. My father, as I mentioned, totally dismissed it for his own reasons. My mother wasn’t interested. Perhaps it was not surprising then that when I was 17, I became not only interested, but obsessively involved in a form of Christianity. Three people fostered my interest – two boys from school, Tommy Mayo and Stuart MacGregor, and Sandra, with whom I’d fallen devotedly in love!

Tommy Mayo invited me to the highly evangelical Bristo Baptist Chapel, hearty singing and the perils of not listening to the still small voice, or the sacrifice of the blood of the Lamb. Stuart, a fine orator, was a perfervid and persuasive evangelical preacher from a soapbox on The Mound by the Galleries in Princes Street. This was at that time a Speakers’ Corner of political and religious zealots, such as the fiery, tweedy Scottish Nationalist Wendy Wood, and the rabidly anti-Catholic McCormack who promulgated tales of every corrupt miscreant priest that ever was.

The coup de grâce