Melanchthon's Astrology. Celestial Science at the time of Humanism and Reformation E-Book

Jürgen G.H. Hoppmann

14,95 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Bookmundo

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Scientific exhibition catalog with a detailed description of the exhibits including further references to literature and academic contributions by Olivia Barcley, Dr. Friederike Boockmann, Prof. Dr. Reimer Hansen, Dr. Helmut Hark, Prof. Dr. Irmgard Höß, Otto Kammer, Heinrich Kühne, Dr. Günther Mahal, Bernd A. Mertz, Prof. Dr. Wolf-Dieter Müller-Jahncke, Dr. habil. Gunther Oestmann, Dr. Ruediger Plantiko, Dr. Krzysztof Pomian, Dr. Karl Rottel, Dr. Ralf T. Schmitt, Dr. Christoph Schubert-Weller, Prof. Dr. Manfred Schukowski, Dr. Gabriele Spitzer, Prof. Dr. theological dr theological h.c. Reinhart Staats, Dr. Ingeborg Stein, Felix Straubinger, Dr. Martin Treu, Father Dr. Gerhard Voss, Prof. Dr. phil. Wolfgang Wildgen, Dr. Edgar Wunder, Prof. Dr. phil. Wolfgang Wildgen, Prof. Dr. Paola Zambelli and Arnold Zenker.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 341

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

JGH Hoppmann (ed.)

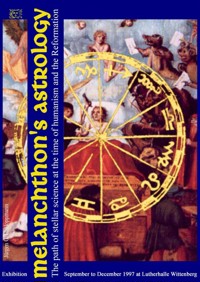

MELANCHTHON’S ASTROLOGY

The path of stellar science at the time of humanism and the Reformation

Catalogue for the exhibition from 15 September to 15 December 1997 in the Reformation History Museum Lutherhalle Wittenberg - text edition revised and revised according to current spelling rules

dedicated to Hans Hoppmann

© 2023 Jürgen GH Hoppmann • ISBN 978-9403694-115 • Publisher: Bookmundo Direct • Typesetting and cover design: ArsAstrologica, using two photos by Jürgen Hoppmann and a painting by Waltraut Geisler, Jauernick-Buschbach • Translated from »Melanchthons Astrologie. Der Weg der Sternenwissenschaft zur Zeit von Humanismus und Reformation« • Publisher: Drei Kastanien, Wittenberg 1997 ISBN 3-9804492-8-9 • translated with DeepL Pro

The work including its parts is protected by copyright. Any use is not permitted without the consent of the publisher and the author. This applies in particular to electronic or other duplication, translation, distribution and public access. Detailed bibliographic information is available from the German National Library at dnb.d-nb.de.

MARTIN TREU: By way of introduction

On the occasion of his 500th birthday, recent Melanchthon research has placed considerable emphasis on the fact that the "Praeceptor Germaniae" was far more than the systematiser of Lutheran theology. His field of work extended to Latin, Greek and Hebrew philology, to historiography and poetry. Melanchthon's efforts in mathematics and astronomy also gained increasing attention in science. At the intersection of these two fields of science lay another field of activity for the Wittenberg professor, which today, however, can by no means be considered undisputed: Astrology.

It was already controversial in Melanchthon's time. Martin Luther in particular did not think much of the interpretation of the stars and expressed this drastically. Nevertheless, he at least tolerated Melanchthon's efforts. Conversely, Melanchthon in turn focused on astrology as a Christian science. For even if new impulses flowed to astrology in the times of Renaissance humanism, there had been a theological tradition since High Scholasticism at the latest, which understood astrology to be perfectly compatible with the Christian faith.

According to the biblical understanding of the world, the starry sky formed part of God's good creation, which was oriented towards man. Man, in turn, as the image of God, could certainly be understood as a "small world" that stood in connection with the "big" one of the cosmos. The only thing that had to be warded off was the danger of a blindly ruling fate, which offered man no room for manoeuvre and at the same time limited the theological insight of God's omnipotence. Within this framework, Melanchthon tried to go his own way when he thought that the stars conveyed an inclination, but not a compulsion.

The influence of astrology in German Protestantism is a complex and little explored topic. Since the Enlightenment at the latest, it has been condemned as charlatanry or, at best, self-deception. It is hardly fitting that even serious daily newspapers still print horoscopes today. According to a recent survey, only 4 per cent of the population believe in the accuracy of horoscopes, but only 40 per cent of those questioned can claim with absolute certainty that astrology has nothing to do with anything (study by the BAT Institute 1997).

The exhibition "Melanchthon's Astrology" cannot and does not want to comment on these contemporary figures. Rather, its task is to document the conditions in the time of the Reformation and confessionalisation. This accompanying volume is also committed to this task. However, the difficulties that arose in terms of content and methodology were so considerable that one should actually point out the provisional nature of the undertaking in the subtitle. The exhibition and accompanying volume represent a first attempt to approach the subject in a variety of ways. Figuratively speaking, it is not possible to offer a fully worked-out topography, but only a first outline, which must be followed by further detailed work. Nevertheless, the topic seems to be important enough and the associated material of such considerable significance that this first exploratory drilling had to be dared. In a hitherto unique way, it required outside help.

Without Jürgen G. H. Hoppmann, neither the exhibition nor the accompanying volume would have come about. As curator of the project, the Berlin astrologer and physiotherapist has worked tirelessly for "Melanchthon's Astrology" and overcome many an obstacle. His name therefore rightly appears on the accompanying volume as editor. Thanks are also due to Edeltraud Wießner, the long-time director of the Melanchthon House in Wittenberg, who established the contacts to Berlin and laid the foundation for a fruitful collaboration. The abundance of lenders required a separate section (cf. Acknowledgements p.108ff.). Without them, as well as the sponsors, the exhibition would not have been possible. The 28 contributors to the present volume deserve special thanks. In their diversity, even disparity, they ideally embody the challenges and problems of the topic. It is no coincidence that both advocates and opponents of astrology have their say in the accompanying volume, as do renowned experts and amateurs. This corresponds to the state of affairs of "star science" in the 16th century and its effects. The controversies within the anthology will undoubtedly be followed by controversies among the readers. This is quite intentional, as long as it remains clear what is to be read in the following: an interim report, a snapshot on the way to better understanding and final judgement. Nothing more, but nothing less either.

Jürgen G. H. Hoppmann will make his experiences from the exhibition project useful for contemporary astrology in a book to be published at the end of 1997 under the title "Astrologie der Reformationzeit", Clemens-Zerling-Verlag, Berlin. We expressly recommend reading it here, not least because the contrast clarifies the aim of our project.

In a letter to Veit Dietrich in Nuremberg of October 1543, dealing with the Last Supper controversy between Luther and the Swiss, Melanchthon concluded that the ultimate cause of the controversy was the ominous conjunction between Mars and Saturn. But this was precisely why pious and learned people had to try to mitigate the influence of the stars so as not to let the conversation break down (CR5, 209). Even if one may have doubts about the analysis with Luther, the goal might still be worth striving for today.

Wittenberg, July 1997

MARTIN TREU Director of the Luther Hall and Melanchthon House

EDELTRAUD WIEßNER: Foreword

"What would it be like if knowledge of the movement of celestial bodies were, say, unknown throughout Europe? ... The access to perfection in science was opened by many intellectual and studious men like Purbach, ... Cusanus, ... Regiomontanus, Copernicus. By their spiritual acumen and resourcefulness ... they illuminated the whole field of science."

Words of an outstanding spirit, a man who worked as a reformer, universal scholar and "Praeceptor Germaniae" at the Wittenberg "Leucorea" from 1518 to 1560 and whose 500th birthday we celebrate this year.

Philipp Melanchthon, born in Bretten on 16 February 1497 and died in Wittenberg on 19 April 1560, is the subject of this catalogue for the special exhibition "Melanchthon's Astrology - The Way of the Star Sciences at the Time of Humanism and Reformation".

When Melanchthon left Heidelberg University in 1512 to continue his studies in Tübingen, he came into close contact with Johannes Stoeffler, the professor of mathematics and astronomy there, and was significantly influenced by him.

Melanchthon gained his mathematical and astronomical knowledge through this man. This also applies to his belief in astrology, which is reflected not only in his letters but also in some of his works. For example, in his "Initia doctrinae physicae", which appeared in 1549, he dealt with the universe and the heavenly bodies. For him, astrology was not only a prophetic part of astronomical science, it was also a part of physics, as this work by Melanchthon shows.

During his time in Wittenberg, Melanchthon studied Ptolemy's "Tetrabiblos" (Four Books on the Star Sciences) in depth and gave lectures on it between 1535 and 1545. He argued that astrology brought great benefits to life and was a true science. Thus the mathematicians and astrologers Georg Joachim Rheticus and Erasmus Reinhold found full support and encouragement at Melanchthon's Wittenberg University. Erasmus Reinhold even wrote the birthday horoscopes of Melanchthon's children. Such "nativitates", as they were called at the time, were also drawn up by Melanchthon for his friends, students and relatives. His intensive study of astrology enabled him to judge the constellation of the stars and make appropriate deductions. Thus Melanchthon himself never set out on a journey without first consulting the stars. Since his birth horoscope stated "avoid the water", he never accepted an invitation or a calling (e.g. to Denmark or England) that required him to cross large waters.

The author of the exhibition, Mr. Jürgen G. H. Hoppmann, through his international connections with astrologers and scientists, has been able to attract authors for his catalogue and to procure exhibits for the exhibition.

May the special exhibition and the catalogue contribute to bringing the aspect of astrology in Melanchthon's life more to the fore for once, and thus bring the visitor and reader closer to us not only the person, but also the time in which he lived, in purely human terms.

A. d. ed:

Edeltraud Wießner, a graduate historian, was museum director for over two decades, first of the Stadtgeschichtliches Museum and from 1978 until the end of 1993 of the Melanchthonhaus Wittenberg. She was then curator of this institution until the end of 1996. She edited parts 1 to 5 of the series of publications of the Stadtgeschichtliches Museum Wittenberg. In relation to the exhibition theme, the second volume is particularly interesting: Die weisse Frau im Wittenberger Schloss - Sagen und Geschichten aus dem Kreis Wittenberg, Wittenberg 1970.

I - Causa Materialis: The Star Sciences

WOLF-DIETER MÜLLER-JAHNCKE: Magister Philippus and Astrology a small collection of quotations

The first is [astronomy], from which we learn, as it were, the time of the orbits of the sun and moon and the other stars, their position among themselves and how they look at the earth. But the other [astrology], by which we learn the changes that arise in bodies from the positions of the heavenly bodies, we learn through the natural qualities of the heavenly bodies. (Unum, quod primum ordine est, et potestate, quo deprehendimus quodlibet tempore motus Solis et Lunae et aliorum siderum, eorumque positus inter sese, aut spectantes terram. Alterum vero, quo mutationes, quae efficiuntur in corporibus, quae congruunt ad illos positus, consideramus per naturales qualitates siderum.

... since I admire this wonderful harmony of the heavenly bodies with the lower, this order and harmony reminds me that the world was not created by chance, but according to divine will. (... cum hunc mirificum consensum corporum coelestium et inferiorum contemplor, ipse me ordo et harmonia admonet, mundum non casu ferri, sed regi divinitus.)

And so I believe that it is an ancient truth that the signs of the changes in the lower matter often depend on the position of the star. This some believe more, others less. (Et arbitror vetustissimam hanc fuisse Sapientiam, insignes materiae inferioris mutationes multas referra ad Siderum positus, qua in re alii plura, alii pauciora scrutati sunt.)

But it is true that through the position of the stars the temperaments are guided and changed. (Verum est autem, stellarum positu gubernari et variari temperamenta.)

... 60 years ago my father had my horoscope done. He got it from the Palatine mathematician and highly gifted man Hassfurt, his friend. In this prediction it was described that my way north would be dangerous and that I would be shipwrecked in the Baltic Sea. I often wondered why I, born near the hills of the Rhine, should fear danger in the Arctic Ocean. But I would not go there if called to Britain or Denmark, for I feared fate, even though I am not a stoic. (..., Ante sexaginta annus meus pater describit Genethliam; curavit a Palatini Mathematico viro ingenioso Hasfurto, amico suo. In ea praedictione scriptum est, intinera me ad Boream periculosa habiturum esse, et me in mare Baltico naufragium facturum esse. Saepe miratus sum, cur mihi ratio in collibus Rheno vicinis praedixerit pericula in Arcto Oceano. Nec volui eo accedere vocatus in Britanniam et in Daniam. Metuo tamen fata, etiamsi non sum Stoicus.)

Philip to Schöner. The hour of Luther's birth, which Philo investigated, Carion transforms to the ninth hour. The mother, however, said that Luther was born in the middle of the night (but I think she was mistaken). I myself prefer another nativity and this one also prefers Carion, although it is unpleasant, because of the place of Mars and the conjunction in the houses [at] 5°, which is a great conjunction with the Ascendant. By the way, in whatever hour he is born, this miraculous position in Scorpio cannot produce a contentious man. (Philippus ad Schonerum Genesim Lutheri quam Philo inquisiuit transtulit Carion in horam 9. Mater enim dicit Lutherum natum esse ante dimidium noctis {sed puto eam fefelli}. Ego alteram figuram praefero et praefert ipse Carion Etsi quoque haec est mirrifica propter locum Mars et Saturn in domos 5° quae habet coniunctionem magnam cum ascendente Caeterum quacunque hora natus est hac mira Saturn in Scorpio non potuit non efficere uirum acerrimum.)

References:

1CR (Corpus Reformatoricum), Bretschneider, C.G. (Hrsg.), Schleswig 1852, S. 10-11 2 CR 10 (1842), S. 263 3 Initia doctrinae physicae, Philipp Melanchthon, Wittenberg 1578, S. 9 4 Melanchthon (wie Anm. 3), S. 82 5 CR 9 (1842), Sp. 188-189 6 Cod. Monac. lat. 27003, Bayerische Staatsbiliothek

Ed. note:

Prof. Dr. Wolf-Dieter Müller-Jahncke, long-time curator of the German Pharmacy Museum in Heidelberg, has headed a private research institute on the history of pharmacy since July 1997. The following of his publications should be mentioned: Magie als Wissenschaft im frühen 16. Jahrhundert, Marburg 1973; Astrologisch-magische Theorie und Praxis in der Heilkunde, Wiesbaden 1984; Kostbarkeiten aus dem Deutschen Apotheken-Museum, Berlin 1993; Philipp Melanchthon und die Astrologie -Theoretisches und Mantisches. In: Melanchthon Prize Melanchthon's Initia Manuscript 3, Stefan Rhein (ed.), Bretten 1997.

HEINRICH KÜHNE: Wittenberg and Astronomy

In contrast to Martin Luther, Philipp Melanchthon occupied himself with astronomy and astrology throughout his life. His father had a horoscope drawn up when he was born, and the humanist did the same when his children were born. He tried to interpret the course of the planets, comets, solar and lunar eclipses. It is truly astonishing how, under the traffic conditions of the time, the first information about the research results of Nicolaus Copernicus reached the small town of Wittenberg. The numerous students from all the countries of Europe certainly demanded information and their opinion from their famous teachers. It is well known what a dismissive attitude Luther took to this and expressed himself solely as a 'theologian. Melanchthon adopted Ptolemy's astrological opinion and his geocentric 'world view'. In doing so, he also initially opposed the new findings of the canon in Frombork (Frauenburg).

Melanchthon wrote the preface to several mathematical and astronomical books, here we may only recall editions of Ptolemy, Purbach (Peuerbach), Schöner, Stifel, Regiomontanus and others. In his inaugural address "Praefation in arithmeticen" from 1536, Georg Joachim von Lauchen, who called himself Rheticus after his native Rhaeticon (Vorarlberg), modestly says that he would only lecture at the repeated suggestion of his teachers and that he had accepted the second professorship of mathematics at the alma mater.

Rheticus (1514-1576) had studied here and in Zurich before finally coming to Wittenberg. He then stayed in Nuremberg, where he found a knowledgeable astronomer and teacher in Johann Schöner (1477-1547). For him, Melanchthon had pushed through an additional second professorship for mathematics at the Senate; he was 23 years old when he took over this position. Melanchthon had obtained a longer leave of absence for his favourite pupil so that he could make the journey to Copernicus in Frombork. Somehow, the great humanist was certainly tempted to learn more about the canon's new teachings, and no one was better suited to do so than the young mathematician.

Rheticus made a diversion via Nuremberg and paid a brief visit to his former teacher Johann Schöner. In Frombork, the young scholar was warmly welcomed by Copernicus: Here he now stayed for almost two years, apart from a short stopover in Wittenberg in 1540. The scientific collaboration eventually developed into a close friendship and a close relationship of trust. Thus, after consultation with Copernicus, it came about that Rheticus, through his writing "De libris revolutionum ... Nicolai Copernici ... Narratio prima" (First Report ... on the Books of the Revolutions ... of Copernicus), which was published in Danzig in 1540 and printed in Basel one year later, Rheticus reported to the scientific world for the first time on the research results of the canon. Copernicus had studied trigonometry in detail and his work on plane and spherical trigonometry "DE LATERIBUS ET ANGVLIS TRIANGULORUM" was printed in 1542 by the famous Bible printer Hans Lufft in Wittenberg. The original before me understandably has neither the name of the publisher nor a signet of the same.

In this context, it is worth recalling the university professor Titius, who said in a commemorative speech on Melanchthon's 2ooth anniversary in 1760: "No book was printed in Wittenberg without Melanchthon's advice or assistance. Todestag 1760 said: "No book was printed in Wittenberg without Melanchthon's advice or aid."

So it is not surprising that Copernicus' famous work: "De revolutionibus orbium coelestium", which he had begun in 1515 and finished around 1530, did not appear in Wittenberg. It was only through the efforts of his friends and not least Rheticus that the canon agreed to hand over the work to the public. Rheticus had made a copy and wanted to have it published in the famous printing workshop in Wittenberg, but the Senate is said to have rejected it, so that it was then published in Nuremberg by Johann Petrejus (Petreins) in 1543. The preface and the change of title by the Nuremberg theologian Andreas Osiander (1498-1552) angered the Fromborker's friends and not least Rheticus. A narrative account gives the following situation: "With joy the canon Jerzy Donner noticed this, he bent over the sick man (Copernicus) and said in a strong voice: 'I bring you, beloved doctor, a joyful message. A messenger came from Georg Joachim Rheticus and brought the first copy of your printed work De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, still almost moist and redolent of printer's ink. At the same time your work was sent to eminent scholars all over the world.'"

With this, Rheticus had done his most important work. He had no interest in teaching in Wittenberg under these circumstances and went to Leipzig and then to Krakow. While the Catholic camp remained quiet at first, the Wittenbergers attacked the famous work, and in 1541 Melanchthon even demanded state intervention. Only in the last years of his life did he change his mind and declare: "What would it be like if the knowledge of the motion of the heavenly bodies, for example, were unknown throughout Europe?... The access to perfection in science was opened by many intellectual and studious men, such as Peurbach, Cusanus, Regiomontanus, Copernicus. They enlightened the whole field of science by their intellectual acumen and resourcefulness."

Melanchthon's son-in-law, the university professor Caspar Peucer (1525-1602), also flatly rejected the new doctrine in his textbook on astronomy published in 1551. But within the scholars at the alma mater, there was a different opinion. Mathias Lauterbach, for example, once wrote to Rheticus in Leipzig: "We will love Copernicus and defend him against the attacks and ill-will of the ill-willed."

Erasmus Reinhold (1511-1553), a student of Rheticus, calculated new planetary tables as a mathematics professor at Wittenberg University, which were based on the Copernican foundation. They appeared in 1551 under the name "Prutenicae tabulae coelestium motuum" ("Prussian Tables of Celestial Movements"). They were so called because Duke Albrecht of Prussia (1490 - 1568) financed their publication and printing. Further publications came out in 1571 and 1584; they dominated computational astronomy until Kepler.

Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) came to Wittenberg to continue his studies here, which he began in Leipzig and continued in Rostock after leaving Wittenberg. In 1599 he came here once more and lived in the Melanchthon House in Collegienstraße until he set off on his journey to Prague to visit Emperor Rudolf II. It would be too much to go into detail here about his scientific work in Prague and that of his colleague Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), the famous discoverer of the primordial laws of planetary motion. It should be mentioned here that the famous astronomer was shortlisted for a position as mathematics professor here. In 1611, a report said: "If then Johannes Keplerus, who is otherwise famous to us for his skill, cannot be obtained" 5. Presumably, the upper consistory in Dresden, which had the right of co-determination, rejected Kepler.

Giordano Bruno (1548-1600) had escaped from the monastery in Naples in 1575 and, after being thrown into prison in Geneva, came to Wittenberg via Marburg. From 1586 to 1588 he lectured at the University of Wittenberg, presenting himself as a convinced follower of the Copernican doctrine. On his departure from the city on the Elbe, he wrote a long poem in which he praised the high standard of education at the alma mater and mentioned the students from all the countries of Europe that he found here. In his books, he put forward a number of theses that were ahead of his time and were only confirmed by later astronomical discoveries. With him, the heliocentric system became the starting point of a new natural philosophy from an initially isolated astronomical doctrine.

In the meantime, the Wittenberg scholars were eager to carry out celestial observations on the ramparts from an observation point. In 1587, this aroused the displeasure of the fortress commander, who managed to get the Saxon Elector Christian I (15861591) to order the astronomers to find another place for their observations. Ambrosius Rhode was taken instead of Kepler. He had been a pupil and collaborator of Brahe and successfully continued his teacher's thoughts at the Leucorea. An interesting scholar was the professor of mathematics, Johann Prätorius (1537 - 1616), he was a direct opponent of astrology and the belief in comets. Of some importance was the scholar Valentin Otto, who was only here for a short time, but completed the great trigonometric work of Rheticus. Mention should be made of Johann Friedrich Weidler, whose history of astronomy has been of the greatest value up to our time.

Ernst Florens Friedrich Chladni (1756 - 1827), jurist and physicist, collected meteorites all over Europe and proved that they are of cosmic origin. Johann Gottfried Galle, who was born in the Dübener Heide and lived from 1812 to 1910, came from a pitch-smouldering family. He attended the Wittenberg Gymnasium, studied in Berlin and, after receiving important documents from the French astronomer Lerrier, discovered the planet Neptune on 23 September 1846.

Finally, I would like to mention the Zeiss Small Planetarium with 44 seats, which was inaugurated in the local Rosa Luxemburg School on 1 September 1987. 6 Furthermore, the enterprising Berlin music publisher Rolf Budde, with great effort and the use of considerable financial means, has arranged for the reconstruction (from 1995 onwards, editor's note) of a tower-like observatory house, as it was once on the property of Wittenberg university professor Johann Jacob Ebert (1780-180). d. Ed.) of a tower-like observatory house, just as the Wittenberg university professor Johann Jacob Ebert (1737-1805) had once erected it on his property at Bürgermeisterstraße 16 in Wittenberg.

Notes:

1 C.R.XI.284 2 Memoria Melanthonis. Wittenberg 1760 3 Ludvrik Hieronimus Morstin: Polnischem Boden entsprossen. In: »POLEN« Nr. 2. Warschau 1973 4 Gerhard Harig: Die Tat des Kopernikus. Leipzig/Jena/Berlin 1965, S.5o 5 J. Chr. Grohmann: Annalen der Univ. Wittenberg. Meißen 1801, S. 192 6 »Freiheit“, Kreisausgabe Wittenberg vom 25.8.1987

Literature:

- J.Jordan/O.Kern: Die Universitäten Wittenberg-Halle vor und bei ihrer Vereinigung. Halle 1917 - W.Friedensburg: Geschichte der Universität Wittenberg, Halle 1917 - W.Friedensburg: Urkundenbuch der Universität Wittenberg. Part II. Magdeburg 1927 - G.Harig: Die Tat des Kopernikus. Leipzig/Jena/Berlin 1965 - J.Adamczewski: Polish Copernicus Cities, Warsaw 1972 - J.Adamczewski: Mikolaj Kopernik und seine Epoche: Warsaw 1972 - H.Wußing: Nicolaus Copernicus -Leben und Wirken. In: Science and Progress. No. 2. Berlin 1973 - S.Wollgast / S. Marx: Johannes Kepler. Leipzig/Jena/Berlin 1976 - O.Heckmann: Copernicus und die moderne Astronomie. In: Nova Acta Leopoldina. NF. Vol. 38, No. 215. Halle 1981

A. d. ed:

For decades, the historian Heinrich Kühne directed the Museum of City History in the Melanchthonhaus Wittenberg. Of his numerous publications, only the most recent are mentioned here: Die Geschichte des Hauses Bürgermeisterstraße 16 und seiner Bewohner in Wittenberg, Wittenberg 1994 - Vom Wittenberger Rechtswesen, von Scharfrichtern und ihren Tätigkeiten, Wittenberg 1995.

EDGAR WUNDER: Melanchthon's Relationship to Horoscopes - an Assessment from Today's Scientific Perspective

The emergence of modern scientific disciplines is associated with many processes of elimination, leaving behind mythical and magical, teleological and historical-philosophical, as well as other pre-scientific and speculative elements. Examples include the separation of astronomy from astrology, chemistry from alchemy, or - in the 20th century - psychology from psychoanalysis.

Philip Melanchthon stands at a historically interesting point in the process of detachment of astronomy from astrology, which was first massively initiated and advanced by Pico de Mirandola a few decades earlier. In contrast to late antiquity, the aim was not to demonise and condemn astrology on religious grounds, but to increasingly show that it lacked a scientific basis. As a representative of neo-Scholastic thought, Melanchthon had to take the conservative side in this dispute with a certain inevitability and defend astrology as well as the outdated heliocentric worldview against the attacks of the critics.

500 years later, this is only interesting from the perspective of the history of science. In terms of content, the positions advocated by Melanchthon in this matter have rightly long since landed on the rubbish heap of history. But while the last representatives of heliocentric thinking finally died out in the 19th century, astrology celebrated an unexpected resurrection in the 20th century as a "sunken cultural asset" : as a pseudoscience beyond any scientific recognition, as a religioid surrogate in reaction to the individualisation thrusts of modernity and the resulting crisis of meaning.

Of course, one should not overlook the fact that neither today's astronomy nor current astrology have much in common with their manifestations in Melanchthon's time. Astronomy has mutated into astrophysics since the middle of the 19th century and today deals with questions that would have seemed unthinkable or unanswerable to Melanchthon and would not have belonged to astronomy.

Modern astrology, on the other hand - after astrological thinking had almost completely disappeared from the scene in the middle of the 19th century - is largely a child of Theosophy, an occult-spiritual secret doctrine founded by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831-1891), whose tailwind and succession made the astrological revival conceivable in the first place and without whose background many characteristics of today's astrology would not be understandable at all.

Both the objectively existing and the subjectively perceived distance between astronomers and astrologers could hardly be greater today. When astrologers speak of a connection between "above and below", of an "embedding of man in the cosmos", then astronomers must notice that the real cosmos known to them does not appear in the horoscope at all. Zodiac signs and houses are arbitrary human settings that have no physical counterpart in the vastness of space. Astrologers are also not interested in the planets as real celestial bodies, their distance, composition, size or even the force fields emanating from them. The only things that are relevant to astrologers are the planetary symbols invented by humans and their associations with ancient planetary deities and their myths. From an astronomical point of view, the talk of the connection between "above and below" is therefore misleading and a farce, if only because the "above", the real existing cosmos, does not appear in the horoscope at all. Instead, the astronomer finds an unreal, arbitrarily cobbled-together distorted image in the horoscope as the supposed "cosmos", which has hardly anything to do with the experienceable universe. This ideological rigidity of astrology can only be explained by a continuous ignoring of almost all new astronomical findings since the times of Melanchthon, when the earth was still in the centre of the world and the distances of the stars were not known, the planets as physical celestial bodies were not yet conceivable and astronomy was reducible to mere mathematics. "No natural scientist says", says the well-known astronomer Joachim Herrmann , "that we humans live in isolation, without any relationship to the universe. But precisely the connections that have really been proven (e.g. tides, solar activity) have not been found and explained by astrologers at all and also play no role at all in the astrological teaching system. The world is more complicated, but also more fascinating, than astrologers pretend". In reality, astrology is "a dry-as-dust, paper affair that has nothing to do with the manifoldness of the universe and the human psyche". And as far as the idea of the cosmic-earthly unity of life was concerned, according to the astronomer Robert Henseling , astrologers had "neither worked it out nor leased it". The astrological system of teaching was "not an appropriate expression of this idea, but an insubstantial, caricaturing abuse of it".

Immunising themselves against the criticism from the astronomical side, but also in the knowledge that "an astronomical justification of astrology is hardly to be thought of at present", according to the astrologer Schubert-Weller , the astrological side responds no less harshly. For example, the long-standing chairman of the German Astrologers' Association, Peter Niehenke , states categorically: "Natural science has not yet reached a conclusion on the question of the validity of the gen. Astronomy least of all!". So not only do astronomers and astrologers disagree, but they already lack a common basis for discussion on which to argue at all.

Melanchthon's endeavour, in the tradition of Ptolemy, to establish astrology in the sense of causal celestial influences as a "part of physics", according to his treatise Oratio de dignitate astrologiae , which he had his pupil Jakob Milich recite at Wittenberg University in 1535, is also completely outdated today. Not only astronomers and other natural scientists state today that such postulated astrological celestial influences have no place within the framework of the now well known laws of nature or would even be in gross contradiction to them , but also astrologers such as Peter Niehenke openly admit that the attempt to conceive astrology "in physical-causal terms is incompatible with the way astrology is practised in practice".

In addition to this "explanatory emergency", many hundreds of empirical-statistical examinations carried out since 1908 are decisive, which were mainly carried out by psychologists and led to devastating results for astrology (cf. note 10 to the overview). Here, at the latest, it becomes clear that the rejection of astrology is by far not only a matter of astronomy or the natural sciences, but is equally vehemently carried out by scientific psychology, which in the course of its investigations was able to identify numerous psychological mechanisms that produce supposedly positive subjective "experiences" in favour of astrology and keep it stable as a paranormal belief system.

It was no different in Melanchthon's time. The verdict of modern science was summed up by the publicist Ludwig Reiners : "Astrology is nothing more than a demonstrably false theory to explain demonstrably non-existent facts". Similar language can be found in numerous public statements by various astronomical societies, such as the 1996 statement by the Council of German Planetariums (RDP) , in which astrology is simply described as "superstition and substitute religion".

If modern astrologers were to try to give horoscopes new legitimacy by referring to the Praeceptor Germaniae, a legitimacy that can no longer be gained anywhere else, then it is not particularly difficult to recognise this as unhistorical and interest-driven thinking. Above all, however, such "attempts at reconciliation" with modern science, based on authorities that have long since become historical, are all too clearly scholastic in character, which is why they are doomed to failure from the outset and must be regarded as wishful thinking.

What can the astrological inclinations of Philip Melachthon still tell us today? In his founding of astrology, Melanchthon essentially followed three lines of argument in his work initia doctrinae physicae . Firstly, he invoked the philosophy of Aristotle, thus substituting authority for an experiential approach. This is a path that should be forever barred to us today. Secondly, he attempted to bring into the field an authority of the Bible also in natural history. In doing so, as Knappich correctly points out, he set a bad example to his students, not least in theological terms. Thirdly, he referred to various pre-scientific, subjective and uncontrolled "experiences", which even his contemporaries of the time, not least Luther, found suspicious. A good example is his claim, still contained in his Oratio de dignitate astrologiae of 1535, that an influence of the stars on the weather was proven by the prophecies of the Flood made in 1524 (cf. 16).

Melanchthon was still quite uncritical of the shoals and dangers of subjective experience , in contrast to empiricism; he allowed himself to be driven and frightened by his astrological world of imagination and, in contrast to many contemporaries, did not prove capable of learning in the face of his own numerous astrological mispredictions. Where could this be better expressed than in one of Luther's table speeches from January 1537: "It pains me that Philipp Melanchthon is so attached to astrology, because people make fun of him a lot. For he is easily influenced by the signs of the heavens and held to the best of his thoughts. He has often lacked, but he cannot be persuaded. When I once came from Torgau, quite ill, he said it was now my fate to die. I never believed that he was so serious" . If we really wanted to draw a lesson for today from all this, Philip Melanchthon could almost serve as a prime example of how we should not approach astrology.

Notes / Literature:

1 Bender, H. (1973): Verborgene Wirklichkeit. Walter, Olten, S. 227. 2 Wunder, E. (1995): Astrologie - alter Aberglaube oder postmoderne Religion? In: Kern, G., Traynor, L.: Die esoterische Verführung. Alibri, Aschaffenburg. 3 Herrmann, J. (1995): Argumente gegen die Astrologie. Skeptiker 8 , S. 49. 4 Henseling, R. (1939): Umstrittenes Weltbild. Reclam, Leipzig, S. 330. 5 Schubert-Weller, C. (1993): Spricht Gott durch die Sterne? Claudius, München, S. 108. 6 Niehenke, P. (1985): Astrologie - Das falsche Zeugnis vom Kosmos? Meridian 6/85, S. 5. 7 Melanchthon, Philipp: CR (Corpus Reformatoricum), Bretschneider, C.G. (Hrsg.), Schleswig 1852, S. 262. 8 Kanitscheider, B. (1989): Steht es in den Sternen? Universitas 44 , S. 330. 9 Niehenke, P. (1994): Astrologie - Eine Einführung. Reclam, Stuttgart, S. 233. 10 Dean, G., Mather, A., Kelly, I.W. (1996): Astrology. In: Stein, G.: Encyclopedia of the Paranormal. Prometheus, Amherst/New York. 11 Wunder, E. (1994): Von der psychologischen Astrologie zur astrologischen Psychose. Astronomie + Raumfahrt 31 , S. 19. 12 Rat deutscher Planetarien (1996): Die Sterne 13 Reiners, L. (1951): Steht es in den Sternen? Paul List, München, S. 191. 14 Melanchthon, Philipp: Initia doctrine Physicae, Wittenberg 1578. 15 Knappich, W. (1967): Geschichte der Astrologie. Klostermann, Frankfurt, S. 203. 16 Müller-Jahncke, W.-D. (1985): Astrologisch-magische Theorie und Praxis in der Heilkunde der frühen Neuzeit. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart, S. 229. 17 Wunder, E. (1997): Subjektive Erfahrung Chance oder Gefahr? In: Köbberling, J.: Zeitfragen der Medizin. 18 Luther, Martin: Tischreden, 3. Band, Nr. 3520. Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger, Weimar 1914, S. 373.

A. d. ed:

Sociologist Edgar Wunder is editorial director of the magazine "Skeptiker" and responsible for astrology at the Society for the Scientific Investigation of Parasciences (GWUP) and the Association of Friends of the Stars (VdS), the largest astronomical association in the German-speaking world.

GÜNTHER OESTMANN: The astrolabe, a universal measuring and calculating instrument

The astronomer Johannes Stoeffler (1452-1531), who had been working in Tübingen since 1507, created an astrolabe with his instructions on the construction and use of the astrolabe (Elvcidatio fabricae vsvsque astrolabii a Ioanne Stoflerino Iustingensi viro Germano: atque totius Spherice doctissimo/ nuper Ingeniose concinnata atque in lucem edita. Imprint Oppenheym. Anno JC. 1513) is something like the standard work on the subject. Melanchthon, who studied with Stoeffler in his Tübingen years 1512-18, contributed a dedicatory poem.

Stoeffler's Elucidatio is one of the most beautiful and widely read books on the astrolabe. Certainly, the construction principles and possible applications presented in the work in an extremely instructive manner contributed decisively to the spread of the instrument in Europe. Until 1620, 16 editions and also a French translation (Paris 1556, 1560) were published.

Until the 17th century, the astrolabe planisphaerium (translated: "starfinder") often served as a didactic aid for astronomical instruction and was used primarily for the purposes of time determination and astrology.

It consists of the following parts: A thicker brass plate, the mater astrolabii, is provided with a graduation on the outermost edge (limbus) and a recess on the inside. A flat disc, the tympanum, can be inserted here. On the tympanum are engraved the tropics of Capricorn and Cancer, the celestial equator, the almucantarates (parallels of altitude) and azimuths (vertical circles intersecting the almucantarates at right angles) for the observer's horizon in stereographic projection . This has two main characteristics:

1. every circle is shown as a circle. Great circles that pass through the projection centre appear as straight lines.

2. the angles remain the same (true-angle projection).