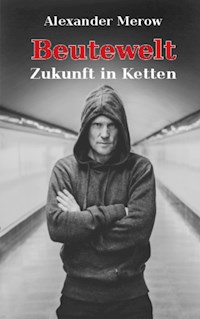

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: BoD - Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: Prey World

- Sprache: Englisch

In the year 2033, the economic situation in Europe is more hopeless than ever before. Artur Tschistokjow, a young dissident from Belarus, takes over the leadership of the 'Freedom Movement of the Rus', a small group of underground rebels that fights against the World Government. While the economic crisis in Belarus increases, the rebels form a growing revolutionary movement. Frank, Alfred and thousands of discontented Belarusians join Tschistokjow`s organization. Finally, they follow their leader to a point of no return...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 283

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Artur Tschistokjow

Making Contact

Conspirational Meeting

Rally in Nowopolozk

Great Speeches and New Problems

It Could be Worse

Cold Days

Special Forces Frank

Limping and Hoping

Stubborn

Growing Crisis

Medschenko Under Pressure

Abnormal End

March on Minsk

Beacon of Hope

'What is the greatest talent of the tick? It is the ability to fall on a dog and crawl through its coat to find a place to suck blood - without being noticed. This is the great skill nature has given to the tick.

But even thousands of ticks can not rule over a dog's life. To the contrary, they can only suck their host dry and kill it in the end, because nature didn't also give the tick the skill to reign. And it is the same with our enemies. In the moment, when they take over this world, their rule will start to crumble...'

Artur Tschistokjow in 'The Way of the Rus', chapter VI 'The Enemy Unmasked'

'We must use the methods of the World Enemy to fight him. I know that it is a terrible truth, but we have no other choice if we want to survive. This is a fight to the death for us, for our nation and also for the rest of mankind. Everyone, who follows me, must be aware of this.'

Artur Tschistokjow in 'The Way of the Rus', chapter VIII 'The Iron Rules of our Movement'

Artur Tschistokjow

It was raining outside and darkness had fallen over the bleak estate of prefabricated houses in the southern part of Vitebsk. Artur Tschistokjow was sitting in his kitchen and thoughtfully played with a little shot glass which was dancing between his fingers.

He took another sip of cheap swill and stared at the wall with his bright, blue eyes. Today, he was more nervous than ever before because the GSA, the international secret service, was upon his heels. Agents of the World Government had come to Belarus and were intensively searching for him. This was no pleasant situation. But here, in this gray ghetto of apartment blocks full of poverty and dreariness, they would not find him.

Artur was not registered anymore, he had no more Scanchip and he left his apartment, which had been rented by an unremarkable person, only in case of necessity. His friends supplied him with food and paid his bills.

There was no other way. Artur was always quiet and appeared to his neighbors as a shadow, when he walked down the corridor of his floor in the night, never saying a word. He had no more telephone and no Internet connection. This was much too dangerous in a time of total surveillance.

Artur Tschistokjow had vanished in order to live a ghostly life. No official data base could find him anymore - and this was his only chance to survive. Artur went to the fridge, an ugly, battered thing in the corner of the room, and took out a sandwich. Then he sat down in the living room and opened the next bottle of vodka. This life was painful, but it was still better than being caught and liquidated. The young man stroked through his stringy, blond hair and his long face with the pointed chin became a tragic mask. He looked out of the window, but there was nobody. Only the rain, the darkness and an old street lamp with a loose connection which was flashing all the time.

Some of the windows in the opposite block of flats were still illuminated. Who lived his life behind those curtains? Perhaps a man who was just as unhappy as Artur After a few hours, he fell asleep on the couch. This day was over.

In the early morning hours of the next day, Peter Ulljewski, Artur's best friend, brought some bread and a dozen sausages. Peter was 34 years old and a craftsman. A few months ago, he had moved to Vitebsk, together with Artur, and was now living in a small apartment in the outskirts. When Artur heard the latest news, he became even more nervous.

'They have arrested two of our men last night. Andrej and Igor', Peter said. 'Both were distributing our leaflets when the cops caught them.'

'Two men less...,' muttered Artur, falling back on the sofa. 'But this looks good, right?' remarked Peter, pulling a thin newspaper out of his pocket. He gave it to his friend. Tschistokjow examined everything and finally nodded.

'Yes, it's a great work, Peter. My editorial about the new administration tax is on the cover page. Nice!'

'We will print about 10000 copies of this edition. I told our young comrades that they have to be more careful, when they distribute our promo material,' returned Peter and took a bottle of soda out of the fridge.

'At first, we will spread our newspapers and leaflets only in Vitebsk - and only in estates of prefabricated houses. In quarters like this we will get the most encouragement from the population', remarked Artur with a serious face.

'What's about the stickers?'

'About 20000 are in print,' replied Ulljewski.

'Okay! Better than nothing.'

Artur tried to smile again, then he went to the window.

'And the group in Minsk?'

'They want 20000 stickers too', said Peter.

'If there is some money left, then we print them as fast as possible,' explained Artur; he drew the curtains.

'Three days ago, you have been on television. They have shown a picture of you and asked the people for information,' told Ulljewski.

'I already know that - from Vladimir,' returned Artur quietly. 'Was something in the papers too?'

'Just a small article about our spraying last Tuesday. Nothing important, but meanwhile they know us. And they seem to pay a bit more attention to our actions.'

'Certainly!' murmured Tschistokjow pensively.

'Anyhow, everything is ready for Saturday. What's about your speech, Artur?' asked Ulljewski.

'I work on it! Don't worry. I know enough things to say.

This is our smallest problem, my friend.'

Some minutes later, Peter said goodbye and left the room silently.

'I'll pick you up at 18.00 pm,' he finally said and shut the door behind him.

Artur looked nervously around, while he thought about all the possible incidents that could happen during the meeting on Saturday. He prayed that everything would run smoothly, because even a little gathering was dangerous enough for him. If the police or the GSA would ever catch him, it would all have been in vain. Two years ago, the young man from Kiev had taken over the leadership of the 'Freedom Movement of the Rus', a patriotic, anti-governmental organization of Belarusians who wanted to liberate their homeland from the tyranny of the World Government.

At that time, Artur had still lived in Minsk. Meanwhile, the once tiny faction had become a small political factor because of its restless and effective publicity campaigns. Many people seemed to have sympathies for the 'Rus', but now the authorities and even the GSA followed their traces and they would not rest, until Artur was in their hands. The enemy knew that he was the leader of the organization, and the hunt for him had already started.

Even television had reported about him several times, in the usual way. He had been called a 'terrorist' and a 'dangerous lunatic'. Furthermore, they had put a bounty on his head, although he had so far just published political pamphlets and had never been violent. If Artur had to leave his apartment by day, he had to creep out like a rabbit who was searched by a pack of gun dogs.

Artur did not catch his neighbor's eyes so far. Otherwise, the police would have already visited him. He shunned the inner city of Vitebsk which was meanwhile cluttered with cameras and eye-ball-scanners. His older brother and his parents had been arrested a year ago. With this tactic they wanted to lure him out of his hiding place but he was still nowhere to be seen. The probability was high that his family members had already been liquidated, because he had heard nothing from them since months. But to look for his parents or his brother would have been suicide.

Because of all this, Artur's hatred had grown enormously. Nevertheless he still felt helpless. Although an increasing number of Belarusians had barely Globes to live and were more discontent than ever before, only a small group of men had joined his organization. Most people were too scared of losing even the rest of their pathetic existence.

The authorities threatened to block the Scanchips of all who supported or joined the 'Freedom Movement of the Rus' in secret. In the worst case, helping the Rus could mean imprisonment or execution. The situation was terrible for everyone involved, and slowly the concerns of the once so creative and fun-loving young man were eating him up from inside.

'I cut off, if necessary, to Japan. If I can't stand this hell anymore,' said Artur sometimes to himself and felt a little more relieved then.

But this feeling never lasted long because the fear in his head was always there.

'Goal!' screamed Frank Kohlhaas enthusiastically and turned around to his teammates.

His best friend and today's opponent, Alfred Bäumer, looked angrily at him and clenched his teeth. Frank had once more humiliated him with his soccer skills.

The goalkeeper shot the ball across the field and the match went on.

'Give me that thing!' heard Frank his teammate Sven shout from the other end of the field.

Kohlhaas jumped up; header, goal. Alfred landed in the dirt again and cursed.

'Bäumer, even my grandma is faster!' laughed a young man of Frank's team. Alf growled at him and angrily kicked the ball out of the way.

The game still lasted for a further hour. Today, it was sunny and warm. An ideal day for a football tournament in the Lithuanian village of Ivas.

Finally, Frank's team could defeat the other three teams from the tiny village and he walked off the field with a satisfied grin.

'What was wrong with you today, dude?' asked Frank the frustrated Alf with sardonic undertone.

'No idea! Maybe I just wasn't fit. Next time, we will sweep you from the field!' grudged Alf and uttered a silent snarl. Julia Wilden gave Frank an admiring glance and the young man answered with a broad smile.

'Franky, go!' she shouted and made a victory sign.

'I dedicate my last goal to you, fair maiden!' called Frank and gave Alf a nudge in the ribs.

'Fuck off!' whispered Bäumer. He sat down on a stool. It was a wonderful day. Julia was giving Frank all her attention and literally idolized him. Her father, the head of the village community, clapped on his back and praised him too.

'I didn't know that you are such a great dribbler.'

Frank was happy. Today, he had thought not a second about the horrors of the Japanese war which had haunted him so many times in the last months.

The politics, the war and everything else seemed to have vanished in the distance. And Frank was glad about that.

'Let's go to Sven for a drink!' suggested Alf and made the impression that he had calmed down.

'Good idea, old man,' said Frank with a short laughter.

They went back to the village and finally visited Sven who was waiting for them with a beer case. The two friends hadn't had so much fun since months.

It was Saturday and the meeting was planned for today. The old warehouse, somewhere in the countryside of northern Belarus, was filled with nearly 200 people who were eagerly waiting for Artur Tschistokjow's speech.

Except for a few abandoned farm houses and large fields, there was nothing around them. The leader of the 'Freedom Movement of the Rus' looked nervously out of the window beside him. Meanwhile, it was 19.00 pm and it was slowly getting dark.

'I hope there are no informers among the people,' said Artur quietly to himself, breathing heavily, full of worry.

The fear that the police would suddenly approach, tortured him since hours. Some of his men stood near the entrance with guns in their hands, willing to defend themselves if the cops would try to arrest them.

The leader of the group of Minsk, Mikhail, opened the gathering and got a thunderous applause. He railed against the Belarusian politicians who served the World Government as administrators of the country. He called them 'traitors', 'criminals' and 'bloodsuckers'.

The discontent men, who had come to the meeting, wanted to hear things like that. It sounded like music in their ears, in a time when all hope seemed to be lost. A comrade from Gomel turned around to Artur and asked him to begin with his speech. Tschistokjow walked up some stairs and went to a speaker's desk which his fellows had made for him.

The front part of the desk was covered with the flag of the organization. Artur's heart started to pound faster, while his comrades applauded. A young boy came to the stage and said reverently, 'I'm proud to meet you personally, Mr. Tschistokjow. I have seen a report about you on television.'

The leader of the Rus smiled at him and beheld the naive appearing group of men in front of him. They looked up to him like believers to a priest. But what could he really give them?

'Not even a mouse has to fear us,' he said to himself. Then he spoke to his followers.

'My dear comrades! I welcome you to this meeting of the 'Freedom Movement of the Rus', our organization, which is fighting the ruling system with all its limited resources.

There are some new men and women here today, some unknown faces. This is the way it should be. I hope that the coming hours will be peaceful, and that no policemen will disturb us. Today, we are about 200 people in this dilapidated building. It is no great number but it is better than nothing.

You all risk your heads, when you come to us and join the fight against the occupation regime. I admire your courage, my comrades. And we will need brave men and women in the coming struggle for freedom. But what else remains for us in these days? Shall we better continue to keep quiet? Shall we just try to survive by crawling from one bad paid job to the next? Trying to become not one of the homeless people, by keeping our mouths shut in front of our masters?

No, this can not be the right way! We must defend ourselves and we will defend ourselves! Last week, the lackeys of the World Government in Minsk have started a new raid against our people. Raising the tax for administration, increasing the prices for electricity. Even lower wages for those, who still have some kind of work, and so on!

They leave us no more air to breathe. They draw the noose tighter and tighter, squeezing the life out of our people. We should remember the better times. Times when a farmer could live from his yield, and a worker from what he had earned. Times when we had something like an own culture and were free men and women. Now, we are slaves, and our country goes, slowly but surely, down the drain. Meanwhile, the Belarusians have just a few children because it has become to expensive to raise a family.

Today, our young people have to emigrate to other countries to find work. Anyone, who loses his job and doesn't find a new one in time, ends as a beggar, becomes homeless - and finally just dies.

In return, the World Government brings hundreds of thousands of foreigners from Asia or Africa to our country in order to get rid of the old Belarusian population. If you walk through some parts of Minsk, Moghilev, Grodno or Gomel, you no longer believe that you are still on Belarusian territory. They want to create a patchwork of different nations, races and cultures on our soil, because this patchwork won't resist them anymore. We, the Belarusians, shall die out and disappear, if you listen to the speeches of Medschenko and his bunch of traitors.

The media pollute our minds with lies and meaningless entertainment every day. They want to brainwash our nation and distract us from our misery. But a small group of people here in Belarus is not poor, not at all! I'm talking about the group of collaborators in Minsk, the group of betrayers. They have a good life by squeezing out their own people! Sub-governor Medschenko is such a tick, and his whole staff of helpers too!'

'Hang this son of a bitch!' shouted one of the men through the hall.

'Medschenko and the rest of the traitor scum must be killed! Put them up against the wall!' screamed a young man, raising his fist.

The other people yelled and applauded. These words were like balm for their frustrated souls. Artur Tschistokjow continued and slowly all the fear was falling from him. He seemed to become a giant who spoke with passion and inner fire.

'We demand that this country shall be independent again! Free from the global system of enslavement! We demand, that this country shall be governed only by Belarusians who serve their own nation! This land belongs to the Belarusians, not to the occupiers, the World Government or other foreigners!' he shouted and his supporters cheered.

Artur banged his fist on the desk and gave his men a determined look, his narrow face was quivering with excitement.

'But we should not fool ourselves. Those, who oppress us, will continue to serve the exploiters and won't become reasonable or sensible tomorrow! They won't use the few Globes, they can still squeeze out of us, to build new schools, kindergartens or to generate more jobs. No! They will only give us more cameras, more paid informers, and will even call more GCF soldiers to our land so that we can feed the oppressors with our money! Furthermore, our country is totally indebted by the 'Global Bank Trust', but there seems to be still enough money to finance all the surveillance!

We must still dwell in the dirt while they tell us that the coffers of Belarus are empty, but this is a lie! They have money but not for the people of Belarus. However, for GCF soldiers, for monitoring and for the foreigners who live on social welfare!'

'Right!' yelled an old man, clapping his hands.

Others also applauded and nodded at Artur. He continued.

'When I decided, some years ago, to resist the destruction and looting of our fatherland, it was clear that I would soon reach a point of no return. Back then, I swore, I would make this country free again and give it back to its rightful owners - the people of Belarus.

I'm often scared that they find and kill me one day, but we all shall not fear our enemies because we are the fighters for the future of our children!

Our movement will not rest until this country is finally free, and our countrymen shall no longer fear hunger and misery! If we die trying, then it shall be! What do we have to lose? I prefer standing in front of you, just for an hour, as a free man, than living a hundred years as a supervised, soulless slave!

And from now on, there will be only one rule of us all: Spread the word! Carry our fight to all parts of Belarus! We have to go to the agency workers in the remaining production centers of our country! We have to go to the countless, homeless people, who have already lost all hope! We have to go to the families, to tell them about the political goals of our movement!

The people of Belarus are becoming more and more desperate and we need to show them that there are other options than just being enslaved!

We must bring the good news to the masses, tell them about the coming liberation. Our brothers and sisters out there are waiting for a change, they are waiting for us, my comrades!'

Artur's speech still lasted for two hours. He spoke about global politics, the Japanese war of independence, the economy of Belarus - shouting his postulations through the meanwhile half-dark hall.

Finally, he presented some of his own concepts. Artur talked about how he wanted to make Belarus free and independent again, how to give the masses work and how revive the old Russian culture. In the end, he was only content with some parts of his speech, but his followers answered him with loud cheers and adored him.

Finally, his supporters gathered around him, trying to talk about everything again. They praised him and for a moment Artur felt euphoric. Shortly afterwards, he discussed the next steps with his group leaders. One of them proudly told him that he has even won a highranking official of the civil service as a sympathizer. The event, which had taken place far away from any nosy eyes in a little village near Vitebsk, ended calmly and all the guests went back home, unnoticed and safe.

Artur finally ordered further actions and told his supporters to distribute the leaflets of the organization. Then he sat in Peter's car for a while and talked with him about his plans to launch new websites, and even to establish an underground radio station, somewhere in Belarus.

Exhausted, but inspired by the encouragement of his followers, Artur returned to Vitebsk in the early morning hours where he disappeared in his apartment for the next days.

It was a bleak evening. Outside it was pouring with rain and the water drops were relentlessly pounding against the window pane. Frank felt dull and tired but something inside him still refused to sleep.

'29...30...31', he was counting silently; counting all the men he had killed.

He reckoned up those, he could remember. In Paris, in Sapporo and during the mission in the jungles of Okinawa.

Surely he could still add some more, especially since the Japanese war, when he had often fired at shadows in the darkness, never knowing who had been hit by his bullets. Frank had thrown hand grenades into rooms and trenches, and had no longer checked how many people had been torn to pieces by them.

Meanwhile, they called him a 'hero' but he did not feel like one. A giant burden of guilt and doubt was lying on his soul. He looked out the window and thought about the great warriors of history, those, who were celebrated and honored as heroes in the memory of posterity. Those men with the magnificent shrines and the great monuments.

'How many people may king Leonidas have slain at Thermopylae?' he asked himself and looked thoughtfully at the old tree in front of his window. 'Has he ever thought of them?'

Frank cursed the world in which he was born into. A world in which he had no other choice, as he assured himself.

'I have always been a happy child. Naive and clueless, nonetheless happy. But after a few years, I had to realize in what cruel age fate has thrown me,' he whispered to himself.

'It's not your fault, Frank! You would save every little animal, help every poor old lady across the street. This is you, Frank! A man with a good core. Nevertheless, you have killed so many people...'

Kohlhaas was sitting on his bed, breathing heavily and holding his head. Outside it had become dark.

Two years ago, the new tax administration tax had been introduced by the World Government in all sectors, including 'Eastern Europe'. At that time, a big wave of discontent had shaken Belarus.

Today, on 15.04.2033, the TV stations and newspapers had announced that the hated tax was raised again with over 50%, while the media were trying to tell the people, that it was necessary. Moreover, even a 'great progress'. Medschenko promised to use the money to support an 'improved Scanchip management', but the most Belarusians, who got more and more problems to get along with their low wages, did not believe him.

Therefore, a lot of people were ranting in secret. The strongly indebted sub-sector 'Belarus-Baltic' tried to fill up its empty coffers with this new measure, because the 'Global Bank Trust', the international financial authority, put it increasingly under pressure.

Meanwhile, many Belarusians knew about this and called the tax for administration 'another brazen raid'. The media claimed, however, that more officials were necessary to ensure a better service and a faster processing of Scanchip matters. Nevertheless, most Belarusians knew that the Scanchips were almost exclusively managed by automated computer systems.

Furthermore, the bankrupt sub-sector had no money to hire new officials at all. But what the people thought, was not important for Medschenko and his staff.

From 04.15.2033, every citizen had to pay further 57,99 Globes a month for the new tax.

Nobody could do anything against this deception, because the World Government had already decided it and anyone else had to obey.