Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

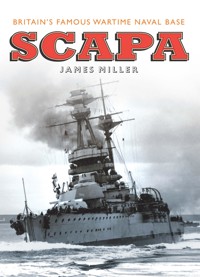

Scapa Flow was one of the world's great naval bases and the scene of many of the major events of twentieth-century naval history. During both World Wars, the Royal Navy made Scapa the home for its capital ships, and thousands of servicemen and women were posted to Orkney. From here the Grand Fleet sailed for Jutland in 1916, from here the escorts for the Russian convoys set off, and it was in this beautiful, bleak anchorage that the German High Seas fleet committed the greatest act of suicide ever seen at sea – 'The Grand Scuttle' – before being later raised and scrapped in the most astonishing feat of maritime salvage in history. It was also in Scapa that the last photographs of Kitchener were taken as he boarded HMS Hampshire, shortly before she was sunk by mine off Marwick Head. Scapa is also the grave of many who fought for their country in both World Wars. In its silent waters lie the wrecks of the battleship Vanguard, blown apart by an explosion in 1917, and the Royal Oak, sunk by U-47 in a spectacular raid at the beginning of World War II . Here the first Luftwaffe raids on Britain occured, here too Italian prisoners-of-war built both the spectacular Churchill causeways and the exquisite chapel on the island of Lamb Holm. In this book, illustrated with over 130 archive photographs, James Miller traces the story of this remarkable place, weaving together history, eyewitness accounts and personal experience to capture the life and spirit of Scapa Flow when it was home to thousands of service personnel and the most powerful fleet in the world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 177

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SCAPA

Fig. 1

Graeme Spence’s map of Scapa Flow, 1812.

This eBook edition published in 2012 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QSwww.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 2000 by Birlinn Ltd

Copyright © James Miller 2000

The moral right of James Miller to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-562-8 ISBN 13: 978-1-84341-005-8

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To condense the story of Scapa Flow, already the subject of several books, into one short volume would have been an impossible task without the generous help of many people, including the staff of the public libraries in Kirkwall and Inverness, Lyness Visitor Centre, Stromness Museum, Orkney Wireless Museum, the Imperial War Museum and the Public Record Office, Kew. I owe grateful thanks to several individuals for giving information and sharing memories with me: in Caithness, Mr A. Budge, Noel Donaldson, Sutherland Manson, Brenda Lees and Trudi Mann (Northern Archive, Wick), and Nancy Houston; in Inverness-shire, Geoffrey Davies, Jackie Fanning and John Walling; in Orkney, Ella Stephen, William Mowatt and John Muir; and in Skye, Vice-Admiral Sir Roderick ‘Roddy’ Macdonald. I am also grateful to John Walling and Alasdair Maclean, who also told me about the Searcher’s role as a beer-supply ship, for pointing out some errors in the first edition. David Mackie of the Orkney Library Photographic Archive gave generous access to his collection of pictures; and I am extremely grateful to John Walling for permission to use several unique pictures from his father’s collection. Once again, I am grateful to Dick Rayner for photographic services and to Duncan McAra for his continuing help and encouragement.

ILLUSTRATION CREDITS

I am grateful to the following sources for permission to use illustrations: A. Budge for Fig. 71; the Imperial War Museum for Figs. 7, 8, 24, 26, 29, 31, 32, 34, 46, 64, 91, 99, 102, 112, 113 and 132; the National Maritime Museum for Fig. 1; Orkney Public Library for Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 12, 13, 14, 16, 19, 25, 30, 33, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 45, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 58, 59, 62, 63, 66, 68, 72, 73, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 90, 93, 97, 100, 105, 106, 109, 110, 114, 115, 119, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130 and 131; Orkney Public Library and the Gregor Lamb Collection for Figs. 17, 18, 61, 65, 74, 81, 82, 94, 95, 96, 98, 101, 103, 104, 107, 108, 111, 116, 117, 118 and 120; the Public Record Office, Kew, for Figs. 44, 67, 69, 70 and 83; Vice-Admiral Sir Roderick Macdonald for Figs. 57 and 92; the Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland for Figs. 60 and 121; and John Walling for Figs. 10, 11, 15, 20, 21, 22, 23, 27 and 28. The pictures obtained from the Imperial War Museum, the National Maritime Museum, the Public Record Office and the RCAHMS are Crown Copyright.

The North Sea and the relative positions of British and German bases in both World Wars.

The Pentland Firth and Scapa Flow

CONTENTS

SCAPA

REFERENCES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

SCAPA

James Miller

One summer morning in 1992, I found a piece of broken china lying among the stones and sea-drift at the head of the beach at Aith Hope. On its side was stamped in brown the crest of the Navy, Army and Air Force Institute, a body better known by its initials – NAAFI. There was a motto: servitor servientium, ‘servant of those who serve’; the piece had obviously come from a mug, a heavy, white mug. It should have been no surprise to find it. Aith Hope lies at the junction between the islands of Hoy and South Walls, at the south-west corner of Scapa Flow. The marks left by the former presence of the main base of Britain’s Home Fleet are on every hand but somehow this shard of a NAAFI mug, redolent of the strong char beloved by the serviceman, spoke more eloquently of the coming and going of thousands than all the abandoned gun platforms and larger pieces of militaria.

I write thousands advisedly. During the First World War, when the battleships of the Royal Navy swung at anchor in the Flow, the number of naval personnel in Orkney at times reached 100,000. In the Second World War, the influx of servicemen and women pushed the islands’ population to 60,000, three times its peacetime size. As well as the crews and shore-based staffs of the navy there were airmen and soldiers from most of the nations fighting under the banner of the Allies; and a posting from the gentler environs of southern England, the home of most of the service personnel, to the stark surrounds of the Flow even gave rise to a rhyming slang phrase ‘scapa flow’, a variant on scarper, meaning to go away, or disappear for parts unknown. It was here that naval aviation took a crucial step forward, that the largest scuttling of a fleet occurred, that the largest maritime salvage operation took place. It is little wonder the name was erected in the popular mind to join El Alamein, Normandy, Anzio and Burma as places associated with war and became a byword for the remote – Addu Atoll, now Gan, a Royal Navy base in the Indian Ocean, was nicknamed ‘Scapa Flow with bloody palm trees’.

An expansive, enclosed basin of sea, some ten miles from east to west, and a similar distance from north to south, the Flow is entirely surrounded by islands. The high bulk of Hoy comprises the western side; the smaller, lower islands of South Walls, Fara and Flotta lie to the south, with, in the east, South Ronaldsay and Burray, and a scattering of smaller islets and holms. The northern and north-eastern shores of the Flow belong to the mainland of Orkney. Although the frequent gales can whip up an angry sea within the anchorage, the ring of land guarantees shelter from the fiercest weather; and the water in the Flow is deep enough – from twenty to thirty fathoms – to float the largest ships safely.

The main entrance to the Flow is Hoxa Sound between Flotta and South Ronaldsay. This was the gate through which the capital ships came and went; destroyers and smaller craft used the gap called Switha Sound just to the west. Another major entrance to the Flow, Hoy Sound, was less used by naval vessels; it lies in the north-west corner between Hoy and Stromness. The island of Graemsay sits in the middle of the channel here and separates Hoy Sound from the Bring Deeps. On the east side, narrow, comparatively shallow channels used to wend between the islands to connect the Flow to the North Sea; these were all sealed in the Second World War by the construction of the series of causeways still known as the Churchill Barriers.

At the beginning of this century, in a hangover from earlier wars, British naval bases were concentrated in the south of England facing the old enemy: France. The emergence of Germany as a naval power, under Kaiser Wilhelm II, changed this pattern. The development and rapid growth of European navies in the twenty years or so before 1914 has been analysed and described many times.1 This maritime arms race crystallised by 1912 into a contest between Britain and Germany, but France, Italy, Austro-Hungary, Russia and others also had an interest in dreadnoughts, submarines, torpedoes and the other new aspects of seapower. It was obvious to strategic experts that, in the event of hostilities, the North Sea would become a major theatre. In 1912, some officials in the Admiralty were even worried that courtesy visits to Shetland by German warships might erode the islanders’ ‘sense of British nationality’; the Orcadians were felt to be less susceptible to enemy influence.2 In 1903, Rosyth had been designated as a major base, and Cromarty was also made a base but with no antisubmarine protection.

Scapa Flow’s potential as a base had been first formally brought to the attention of the Admiralty as long ago as 1812, by Graeme Spence. The latter was the nephew of Murdoch Mackenzie, the first man to map the Flow and its surroundings by the then modern technique of triangulation. Mackenzie’s atlas of northern waters had been published in 1750 and had opened the way to greater use of the Pentland Firth by sailing vessels; hitherto they had tended to avoid the dangerous passage. Spence, himself a maritime surveyor for the Admiralty, sent a carefully drawn chart of Scapa Flow to their Lordships along with his ‘Proposal for establishing a Temporary Rendezvous for Line-of-Battle Ships, in a Natural Roadsted [sic] called Scapa Flow, formed by the South Isles of Orkney . . .’.3

Spence argued that Scapa Flow was the finest roadstead after Spithead for line-of-battle ships and anticipated the critics of his plan by pointing out that local seamen ‘would think light of’ the alleged dangers of navigation in the area. On the scale of two inches to the British mile, and coloured in green, brown, yellow and red, his chart is an object of beauty. It failed, however, to convince the Commissioners of the Admiralty to take any action: a note dated 7 July 1812 instructed a clerk to thank Spence for his draft – and that was all.4

But not quite all. During the Napoleonic Wars, the Royal Navy found itself with increased business in the north, both in recruiting and in combating the menace of privateers. The latter, mainly French and later American, attacked merchantmen of all types, seizing cargoes and ships, and posed a serious threat to the Baltic trade, a major source of timber, vital to Britain. A convoy system was introduced for merchant ships, with the assembly point in Longhope. Two Martello towers, at Crockness and Hackness, were built to guard the entrances to the anchorage but they were not finished until December 1814 when peace was signed with the Americans and Napoleon was on the verge of defeat.5

Throughout the nineteenth century, Scapa Flow saw little naval activity, apart from surveying parties updating and enlarging upon the earlier charts of Mackenzie and Spence. HMS Triton was engaged on this work in 1909, when the Royal Navy began to make use of Scapa Flow in a big way. Ships of the Channel Fleet had paid the occasional visit to Kirkwall Bay – for example in 1898 to show the flag and indulge in public duties – but now the activity was on an altogether grander scale. In April 1909 Orkney was looking forward eagerly to welcoming the visit of the combined Atlantic and Home Fleets. The Orcadian published the news that the Fleets would arrive on Saturday the seventeenth and stay until the following Wednesday. Traders made ready to supply the ships with a daily requirement of eighty tons of vegetables and 5,000 loaves. One hundred and thirty cattle had been purchased in the North Isles and the slaughterhouse in Kirkwall went on overtime to cope with the demand for its services. A procession of coal steamers arrived.6

At around ten-thirty on the morning of the seventeenth the ships of the navy came out of the haze in the Pentland Firth and passed through Hoxa Sound into the Flow to form a line of twenty-eight battleships and cruisers, ‘a most imposing appearance’ in the words of The Orcadian’s reporter. With their attendant flocks of destroyers, the whole fleet numbered eighty-two vessels. The cold southerly wind did not deter the townsfolk of Kirkwall from flocking out to see this manifestation of Britain’s naval might; pleasure trips were organised to view the Fleets on Sunday, and the provost and town officers welcomed the navy and declared that the town’s Bignold Park and golf course were open to the men. The Home Fleet was under the command of Admiral Sir William H. May, who flew his flag in HMS Dreadnought, and the Atlantic Fleet was led by Vice-Admiral Prince Louis Alexander of Battenberg on HMS Prince of Wales.

Fig. 2

The Royal Navy in Scapa Flow before the First World War.

The people of Flotta had perhaps the best view of the ships as they ringed the island in the Flow. The Orcadian’s correspondent there wrote of them ‘steadily, grandly, unitedly stemming the racing ebb tide of the Pentland Firth’ and wished that the Kaiser could have been there – perhaps he would have then thought twice about competing for naval supremacy.

The Royal Navy returned with a fleet of ninety ships in 1910. By this time considerable pressure was being put on the Liberal government of Herbert Asquith to make Scapa Flow a permanent base. Matters were given more urgency when Winston Churchill was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty at the end of 1911. In February 1912, the Admiralty became concerned over the War Office intention to disband the Orkney Territorial Royal Garrison Artillery (TA) forces and asked the Home Ports Defence Committee to consider strengthening Scapa Flow and the Cromarty Firth against torpedo attack. A contingent of seven senior military officers, including the Director of Fortifications and Works and the Director of Artillery, travelled to Wick in March, where they were met and taken to Scapa by HMS Blonde on an inspection.7

During naval manoeuvres in the summer of 1912, the Royal Marines carried out a defensive exercise on Flotta. On the afternoon of 12 July, they landed in Kirk Bay and by the evening of the following day had placed all their searchlights and had wrestled five of their eight four-inch guns across the peaty ground to strategic positions at Scatwick and Stanger Head to guard the entrances to the Flow. It was reckoned that these guns, augmented by a further four at Hoxa, would be enough to protect Hoxa Sound against torpedo craft. Destroyers carried out a mock attack and were considered to have been satisfactorily repulsed.

The idea behind this exercise was that the Royal Marines could form a ‘flying corps’ of 3,000 men, trained to seize and hold bases for naval use, and that the defence of Scapa Flow could be assigned to a portion of this body. As ever, the costs of defence were foremost in some minds. In June 1912 the Chief of the War Staff was minuting: ‘Assuming that it is necessary to maintain in time of peace a permanent garrison of 250 Marines in order to protect the anchorage from an unexpected coup de main the only further economy to be anticipated would be by appropriating 4.7-inch guns already in stock which would reduce the estimated cost from £40,000 to a nominal £10,000 and the substitution of huts such as at Aldershot for solid barracks. It is possible, however, that the stormy weather in the Orkneys may be an argument against this class of accommodation.’ In July the Marines stayed in tents, but the assessors of the exercise recognised that any length of stay would require huts capable of ‘standing strong winds’. In the Second World War, many of these lessons had to be re-learned.

The July ‘invasion’ of Flotta seems to have been generally regarded as a success. Before the Marines had landed in Kirk Bay, the permission of the Marquis of Zetland, the owner of the island, had been quietly sought. After the exercise, the farmers on Flotta had put in some small claims for damage to grazings and turf, and were compensated by being left the quantities of stakes and barbed wire the Marines had abandoned.

The War Office estimated the cost of fortifying the Flow a little short of £400,000; this was too much, and the sum was revised downward in 1912 to £190,000 for the initial build-up and a further £29,000 for maintenance. This was achieved by having fixed defences for only some of the channels and by using the local TA personnel instead of regular artillery forces. It was recognised that Scapa Flow would be an unpopular posting for the Royal Marines but the planners hoped that, by counting the tours of duty in the islands as sea-time, this particular pill would be satisfactorily sweetened.

The advantages of the Flow as a war anchorage were seen as threefold: it was big enough to hold the entire Grand Fleet; its isolated, insular position gave security against spies observing ship movements; and the hydrographic conditions of the approaches made submarine attack ‘practically impossible’. In 1912 the potential of the submarine was unrealised and attack by surface craft armed with torpedoes – German destroyers or small fast cruisers operating from the Norwegian coast – was seen as the ‘only danger’. The Flow was to be defended by blocking narrow entrances and guarding the others. A third option, to have the Fleet defend itself, was dismissed as demanding too much from the seamen: the effect of maintaining constant readiness was unknown, and there had to be a place where the ships’ crews could relax in security.

The visits to Scapa Flow had made navy captains familiar with northern waters. The Navigation Department of the Admiralty could write in June 1914 that the Flow posed no problems as an anchorage for battle-cruisers, battleships and large fleet auxiliaries and ‘no navigational problems in leaving at any state of the tide’.8 The earlier decision to develop the Cromarty Firth rather than the Flow as a permanent base, with the Flow being held as a war anchorage without fixed defences, was reversed in 1913 when the provision of fixed defences for the Flow was recognised to be ‘a matter of urgency’. It was decided that the Admiralty would be solely responsible for the defence of Orkney and Shetland. Fixed gun defences under naval control, now reckoned to cost about £80,000, and a garrison of 250 Marines on HMS Scylla as depot ship were proposed. By July 1914, the Admiralty had another need to consider – how to defend a new oil fuel dump, holding 50,000 tons of oil.

Fig. 3

Hammocks stowed in a Ness Battery accommodation hut during the First World War.

Fig. 4

Dining al fresco at the Ness Battery during the First World War.

With Scapa Flow now strategically important, the military authorities became very sensitive to any suspicion of espionage. There can be little doubt that the Kaiser did have agents keen to know what was happening in this new base but the anxiety about spies could take a ludicrous and comic turn. In 1909, two German balloonists had arrived unexpectedly in Orkney when a southeasterly gale caught their craft after they had lifted off from Munich and drove them a thousand miles across Europe to land in the islands; if this could happen accidentally in peacetime, what would the enemy try in war? On the day before the First World War began, Lieutenant James Marwick of the Orkney Royal Garrison Artillery arrested two men who had been sketching the Hoy cliffs. They turned out to be schoolteachers on holiday – one came from Edinburgh, the other from Southampton – but Marwick had concluded they had had a foreign air about them.9 Early in August 1914 a German trawler was captured and brought into Scapa; the Orkney Herald reported that carrier pigeons had been found aboard her and she may even have had a wireless set.10

There are rumours and counter-rumours about the amount of spying that went on in Orkney in both world wars; the theme of espionage at Scapa Flow fuelled the plot of a 1930s thriller movie, The Spy in Black. One story that gained wide circulation in the Second World War asserted that the success of the attack on the Royal Oak in October 1939 was partly the result of the work of a Nazi agent who lived in Kirkwall under the cover of being a watchmaker; no mention of this character was found in German records after the War.11 In the summer of 1938 a stranger selling religious literature spent some time on the island of Stroma: Sutherland Manson, the son of the island schoolmaster, remembers him as being ‘young, very effusive, blond’, given to expressing ‘an intense desire to obtain a house overlooking Scapa Flow’ but never revealing anything of his place of origin.12

Fig. 5