Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

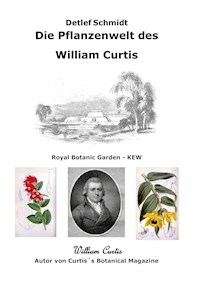

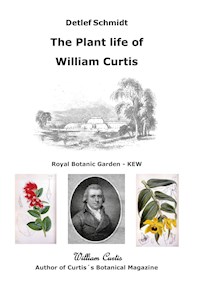

William Curtis (11 January 1746 in Alton, Hampshire; 7 July 1799 in Brompton) was an English botanist, apothecary and entomologist. His official botanical author code is "Curtis". Curtis was head of the Chelsea Physic Garden. He founded botanical gardens at Bermondsey, Lambeth in 1771 and Brompton in 1789. In 1787 Curtis founded the Botanical Magazine and was its editor until his death.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 111

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Detlef Schmidt

Born 1955 in Berlin

Biological laboratory technician, amateur photographer and amateur entomologist

Important note for the user

The author has taken all reasonable care to include complete and accurate information in this book. The author makes no warranty, assumes no legal responsibility, and assumes no liability whatsoever for the use of this information, for its efficiency or improper functioning for any particular purpose. The author does not warrant that the procedures, programs, etc. described are free from third party proprietary rights. The author has made every effort to identify all copyright holders of illustrations and texts and to list them in the picture credits and with the text source. Should the author nevertheless be provided with proof of ownership of the rights, the fee customary in the industry shall be paid.

The author

August 2021

Fig. William Curtis

(* 11 January 1746 in Alton, Hampshire; † 7 July 1799 in Brompton) was an English botanist, apothecary and entomologist. His official botanical author code is "CURTIS".

The plant genus Curtisia AIT. from the dogwood family (Cornaceae) has been named after him.

Curtis was head of the Chelsea Physic Garden. He founded botanical gardens at Bermondsey, Lambeth in 1771 and Brompton in 1789. In 1787 Curtis founded the Botanical Magazine and was its editor until his death.

Curtis's Botanical Magazine is one of the greatest scientific journals of all time. Started in 1787, the journal is still published today. It is the oldest existing journal with coloured plates, of which more than 11,000 have now been produced. The volumes are the work of many renowned botanical artists and provide an exceptional pictorial record of floral fashions and plant introductions in Britain over the last two centuries.

The first issue of the journal, which was to portray ornamental and foreign plants, appeared on 1 February 1787. A small publication in octavo format, it consisted of three hand-coloured plates with brief descriptions in letterpress. Priced at one shilling, it was an immediate success; the first issue sold over 3000 copies.

Fig. Collection of Flowers

Fig. Flower Garden Displayed

The first copper plate depicting the Persian iris was drawn by James Sowerby. Described as "highly esteemed by all flower lovers" for its "beauty, early appearance and fragrant flowers".

Plate 1 (Volume 1 von 1787) Persian iris (Iris Persica L.)

James Sowerby was born in London on 21 March 1757 and died in Lambeth (London) on 25 October 1822. Sowerby was a British naturalist, zoologist and painter. His official botanical author code is "SOWERBY".

James Sowerby Paintings by Thomas Heaphy (1816)

Sowerby was the son of the engraver John Sowerby and his wife Arabella Goodreed. In 1771, at the age of 14, he joined the studio of the marine painter Richard Wright as an apprentice. When Wright fell seriously ill, Sowerby moved to William Hodges.

On 1 December 1777, Sowerby began studying art at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, specialising in miniature painting. It was precisely these skills that caught the eye of William Curtis, who immediately engaged him as an illustrator for his Flora Londonensis. Through his collaboration with Curtis, Sowerby also made the acquaintance of the botanists Charles Louis L'Héritier de Brutelle and William Withering, for whom he later also worked.

Through his fellow student Robert de Carle in Norwich, Sowerby came into contact with natural scientists such as James Edward Smith and Dawson Turner. This meeting gave rise to English Botany, known today as "Sowerby's Botany", between 1790 and 1814.

Plate 26 (Volume 1, 1787) Variegated Stapelia(Stapelia variegata L.)

Sowerby's artistic work earned him the title of "Fellow" of the Linnean Society of London in 1793, and he was admitted as a full member just five years later. During these years, Sowerby also became friends with the natural scientist Joseph Banks.

On 25 October 1822, James Sowerby died at home in Lambeth, London, after a long illness at the age of 65. His two sons James de Carle Sowerby and George Brettingham Sowerby I continued their father's work after his death.

The plant genus Sowerbaea SM. from the asparagus family (Asparagaceae) and the Sowerby toothed whale (Mesoplodon bidens) from the beaked whale family (Ziphiidae) were named in honour of James Sowerby.

William Curtis recognised his passion for flora and fauna at an early age. However, he first did an apprenticeship as an apothecary. However, after moving from Hampshire to London in 1766 to pursue this trade, his botanical interests prevailed and he gave up his career to earn a living by teaching and writing. His first publication was a pamphlet on collecting and preserving insects. In 1773 he was appointed demonstrator of botany at the Chelsea Physical Garden. After leaving this post in 1777, he opened his own London Botanic Garden at Lambeth Marsh. He later moved the garden to Brompton.

Curtis' first major publication was Flora Londinensis. This work, begun in 1774, aimed to illustrate the plants growing in London. At that time, however, there was generally more interest in showy exotic plants than in the native 'weeds' of London. Despite its beautifully produced colour plates, it was a financial failure and was never completed. However, there was a need for a work on the many new plants from overseas that garden lovers wanted to grow at home. Curtis saw an opportunity to recoup some of the losses he had suffered and published his Botanical Magazine. He initially used the artists he had already employed for the Flora Londinensis, such as James Sowerby and William Kilburn, who could draw plant specimens from his own botanical garden.

However, the artist who dominated the early years of the magazine was Sydenham Teast Edwards. Curtis became aware of his talent and arranged for him to train as a botanical artist in London. He was only nineteen when his first plate was published in the Botanical Magazine in 1788. More than 1700 followed over the next 27 years - some posthumously - to the practical exclusion of other artists. The plates illustrated on page 9 and page 10 are an example of his work. At first Edwards drew and engraved the plates himself, but from 1792 Francis Sansom took over the engraving. A few years before his death, Edwards left the Botanical Magazine to start his own Botanical Register. The reason for this was that 12 of his plates were mistakenly attributed to Sowerby.

Table of Content

Red Plumeria

Perpetual Rose

Diploppus incanus

Winterling

Iris reichenbachii

Paeonia peregrine

Pleione pricei

Abies cephalonica

Amorphophallus titanium

Contents Botanical Magazine No. II 1828

Adansonia digitata

Adansonia digitata

Malva morenii

Croton castaneifolium

Oncidium papilio

Orobus sessilifolius

Neottia aphylla

Nepenthes distillatoria

Gonolobus niger

Polemonium richardsonii

Pothos macrophylla

Baeckea frutescens

Banksia marcescens

Dorstenia tubicina

Calceolaria plantaginea

Maxillaria pallidiflora

Grevillea acanthifolia

Lotus microphyllus

Penaea inbricata

Corchurus olitorius

Salpiglossis atro-purpurea

Arum campanulatum

Pitcairnia bracteata

Lycopersicon peruvianum

Gomphrena globosa

Justicia calycotricha

Bignonia colei

Blechnum longifolium

Zygopetalum rostratum

Cactus alatus

Sida globiflora

Houstonia serpyllifolia

Octomeria serratifolia

Buddleja madagascariensis

Dioscorea cinnamomifolia

Cycas circinalis

Solanum balbisii var. purpurea

Franciscea hopeana

Oxalis rosea

Encyclia viridiflora

Oenothera lindleyii

Artocarpus integrifolia

Dracaena australis

Chaetogastra lanceolata

Nicotiana glauca

Osbeckia glomerata

Malva angustifolia

Hedyotis campanuliflora

Tillandsia psittacina

Primula verticillata

Gaultheria shallon

Epidendrum fuscatum

Justicia quadangularis

Begonia papillosa

Rosa sinica

Alstroemeria ovata

Begonia dipetala

Conospermum ericifolium

Cattleya intermedia

Polygala paucifolia

Buddleja connata

Eriostemon salicifolium

Saponaria glutinosa

Imatophyllum aitoni

Sida sessiliflora

Sieversia triflora

Pultenaea pedunculata

Dodonaea attenuata

Iris lutescens

Cynara cardunculus

Sieversia peckii

Salvia pseudo-coccinea

Blumenbachia insignis

Oxalis carnosa

Desmodium nutans

Passiflora capsularis

Artocarpus incisa

Salvia involucrate

Oenothera viminea

Calceolaria arachnoidea

Didiscus caeruleus

Contents Botanical Magazine VOL. V 1849

Cereus leeanus

Cirrhopetalum nutans

Mirbelia meisneri

Scutellaria macrantha

Heterotrichum macrodon

Cirrhopetalum macraei

Exacum zeylanicum

Lisianthus pulcher

Miltonia spectabilis var. purpureoviolacea

Macleania punctata

Aerides crispum

Loasa picta

Dendrobium devonianum

Gloxinia fimbriata

Gesneria picta

Vanda tricolor

Bejaria coarctata

Maxillaria leptosepala

Curcuma cordata

Pachystigma pteleoides

Eriopsis rutidobulbon

Stifftia chrysantha

Eriostemon intermedium

Coelogyne fuliginosa

Thyrsacanthus bracteolatus

Pesomeria tetragona

Cereus reductus

Cyrtanthera catalpaefolia

Lycaste skinneri

Sobralia macrantha

Lapageria rosea

Stemonacanthus macrophyllus

Asystasia scandens

Dendrobium cambridgeanum

Zieria macrophylla

Alloplectus capitatus

Amherstia nobilis

Cyrtochilum citrinum

Mormodes lentiginosa

Epimedium pinnatum

Rhododendron formosum

Dielytra spectabilis

Lacepedea insignis

Nematanthus ionema

Gaultheria bracteata

Mitraria coccinea

Sida (Abutilon) venosa

Penstemon cyananthus

Sauromatium guttatum

Roupellia grata

Aristolochia macradenia

Cyrtantbera aurantiaca

Nymphaea ampla

Cupania cunninghamii

Metrosideros florida

Gonolobus martianus

Escallonia macrantha

Brassavola digbyana

Heliconia angustifolia

Schomburgkia tibicinus var. grandiflora

Dendrobium tortile

Rhododendron clivianum

Cychnoches barbatum

Espeletia argentea

Brachysema aphyllum

Ixora laxiflora

Begonia cinnabarina

Tabernaemontana longiflora

Clerodendron bethuneanum

Contents VOL. V 1909

Encephalartos barteri

Angadenia nitida

Eria rhynchostyloides

Clerodendron (Cyclonema) ugandense

Lonicera (Nintooa) giraldii

Alpinia bracteata

Oligobotrya henryi

Eranthemum wattii

Pinus bungeana

Sorbus (Aucuparia) vilmorini

Cycas micholitzii

Saxifraga scardica

Pseuderanthemum seticalyx

Nigella integrifolia

Rubus (batothamnus) koehneanus

Impatiens hawkeri

Microloma tenuifolium

Arbutus menziesii

Strophanthus preussii

Anthurium trinerve

Dendrobium bronckartii

Larix occidentalis

Mussaenda treutleri

Deutzia setchuenensis

Pyrus pashia, var. kumaoni

Pinus jeffreyi

Begonia (scutobegonia) modica

Sorbus cuspidata

Prunus (cerasus) japonica

Cornus macrophylla

Coelogyne venusta

Aloe rubrolutea

Rubus (eubatus) canadensis

Pyrus ringo

Mahonia arguta

Caralluma nebrownii

Cycnoches densiflorum

Erlangea tomentosa

Spiraea (Chamaedryon) henryi

Agave (Littaea) wrightii

Aphelandra tetragona

Megaclinium purpureorachis

Exostemma subcordatum

Euphorbia ledienii

Peliosanthes violacea, var. Clarkei

Cereus amecamensis

Cissus (Cyphostemma) adenopodus

Laurelia serrata

Rhododendron coombense

Bulbophyllum (Cirrhopetalum) campanulatum

Magnolia delavayi

Pieris formosa

Cotoneaster moupinensis

Cephalotaxus drupacea

Kitchingia uniflora

Parthenocissus tricuspidata

Asparagus tetragonus

Prunus (Euprunus) maritima

Opuntia imbricata

Euryops virgineus

Notes on synonyms using the example of Croton castaneifolium

Example of the taxonomy of Cactus alatus

Original printout from Curtis's Botanical Magazine

Hand coloured copper plate engraved by Swan

Editors and illustrators of Botanical Magazine

Example of an original entry from Curtis's Botanical Magazine

Royal Botanic Gardens (Kew)

Source reference

The following were helpful in putting the book together

Plate 279 (Volume 8, 1794) Red Plumeria (Plumeria rubra L.)

Plate 284 (Volume 8, 1794) Perpetual Rose(Rosa semperflorens W.M.Curtis)

The beautiful hand-coloured plates are the main attraction of the magazine. The illustrations of the first copies of the magazine are still largely bright and fresh after two hundred years.

As Curtis states in the preface to the first edition, the plates were "always drawn from the living plant and coloured as close to nature as the imperfections of the colouring permit".

Since artistic freedom was hardly possible, each artist had to draw the preparations accurately and precisely in order to create a scientifically authoritative work.

Up to volume 70, the plates were produced with copperplate engravings, with each copy coloured with watercolours. Considering that in the early years of the journal up to 3,000 copies per issue (with an average of 3 plates) were published, one can imagine that it was impossible to achieve a uniform colouring.

Different colourists achieved different results, and even the pigments used were not necessarily of the same quality.

At times, about 30 people were busy colouring the illustrations of the Botanical Magazine.

Not only was the repetitive work tedious, but low wages did not promote high standards and there were inevitable variations in care and accuracy as a result.

Incredibly, despite these problems, the magazine's plates were all hand-coloured until 1948, when a shortage of colourists forced the magazine to adopt photographic reproductions.

The choice of plants to be described was often influenced by the public's great fondness for the unusual. Initially, European plants were predominantly selected, but in the nineteenth century more and more plants were obtained by botanists from further afield. David Douglas (1799-1834), for example, collected extensively in America on behalf of the Royal Horticultural Society. He travelled across America for eleven years, sending seeds and specimens home at regular intervals. Many of his plants thrived in England and were illustrated in the Botanical Magazine. One of his finds, Diplopappus incanus (Lindl.), is illustrated on page 12; the accompanying text explains that the species is native to California, where it was discovered by David Douglas.

Plate 3383 (Volume 62, 1835): Diploppus incanus (Lindl.)