2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

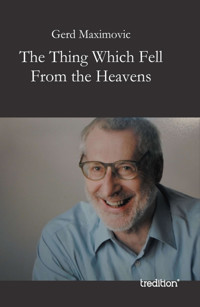

- Herausgeber: tredition

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

Gerd Maximovic is one of the highest acclaimed SF-Writers of Germany today. In this volume, you find some of his finest stories, including the winner of the European SF Award, "The Red Crystal Planet". His stories have been published in Playboy and Omni and in a lot of anthologies as well as in six of his collections. The title story, "The Thing Which Fell From the Heavens", has already met enthusiastic readers. In this story a monster is penetrating into Medieval Old Germany, causing havoc and much surprise and wonder. Or take "Rachel and Georges", where men and women can swap bodies, and then look what may happen... In other stories the well-known Frankenstein creature as well as Jack the Ripper are working. All of these characters are different from what you know about them till now. All of these stories are of high literary quality, but always entertaining, even thrilling. You don't like to get bored? Neither does the author. Please mind, these stories are not only sheer entertainment, but in all of them you find a lot to think about. Stephen Potts on one of the author's German collections: "An earnest, entertaining, often fascinating volume, deserving English translation."

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 945

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Gerd Maximovič

Gerd Maximovič

The Thing Which Fell From the Heavens

tredition

© 2014 Gerd Maximovič

Translated by Isabel Cole

Published by

Tredition GmbH, Hamburg

ISBN: 978-3-8495-7915-9

ISBN: 978-3-8495-8351-4 (eBook)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the author and the publisher, excepting brief quotes used in connection with reviews, written specifically for inclusion in a magazine or newspaper.

Detailed bibliographical data from:

Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

http://dnb.d-nb.de

Contents

Alpha Station

The New Humans

Broadnar’s Creature

Frankenstein

The Darkcloud

Aurora

Expedition into the Past

The Hunt of the Man-Killing Dogs

The Gill People

The Exploration of the Omega Planet

Jack the Ripper

The Brooklyn Project

The Callisto Incident

The Journey into the Red Fog

The Great Dog Planet

Messages from the Stars

Rachel and Georges

The Red Crystal Planet

The Thing Which Fell From the Heavens

The War Against the Parmanters

Omikron

The Karem Materials

The Lux-Accelerator

Salt

Crux

ALPHA STATION

The sun hung in the sky like a glittering eye. Beyond its flaming body the stars turned mutely. The band of the Milky Way was as if spilt across the sky by a trembling hand. In the immense black vault which looked as if it had been forged with a gigantic hammer, the enormous Earth revolved as a ball washed with blue floods and flecked with cotton. Into the space which lay so silently, the HOUND vaulted above a yellow flame with a silent roar.

The crew of the shuttle - Scott, the captain, at its head - lay pale from the acceleration which they had just endured, but also from the message in the cushion which they had received in the reception bastion from orbit. Seldom had a projectile been hurled into the sky with such fury - indeed, with tears of disappointment - as the HOUND, the little ship armed with all manner of weapons, which now flew in pursuit of the time which, so to speak, had been slept through on Earth.

First the radar, then the electric eye reached out to the Alpha station, which revolved close above the haze of the atmosphere’s margin. Very slowly the now silent, the now mute fortress approached, from which they had only just heard bellowing noise - the raving shrieks, the cracking and grinding, the forms of mortal fear in which the researchers and their creations had opened their souls. It was, moving onto the screen, a gigantic ring which flared silver in the sunlight.

Of the many bastions which orbited the Earth, there was none in which so many top secret activities were carried out as on board Alpha. Because no one wanted to believe in an accident, in a failure on the platform, even Scott and his crew had been scantily in formed, in great haste, about what was believed, in the lack of more precise information, to have happened out there - as they hurried to their little ship before the liftoff.

And now - as the HOUND already began to shine ahead its searching beams and its gliding lights- that brightly-illuminated ring had risen silently in space, already visible to the naked eye - that jewel, that non plus ultra of technology, hardly to be surpassed. And the wheel sailed there in the glare of the sun and the glory of the light with such dignity that it itself glowed - as if, in this exalted place, literally in all the ages nothing could ever happen which would defy human reason.

*

In the night Dr. Brownmiller had been seized by a strange unrest. Periodically he lay awake in his sleeping cabin, opened his eyes to stare into the darkness illuminated by the weak glow of the emergency lamps. Now he rested, nearly trembling, in his bed and tossed back and forth again and again, sweat covering his body. Now that he was no longer asleep he could hear the humming of the station.

Dr. Brownmiller, the supervisor of the project, had been there from the beginning. Thus, after the many weeks which he had spent on board Alpha, he was able to distinguish between the slightest noises which rose from the depths of the wheel. As he listened, he caught the humming of the generators which produced the power used by the ring by capturing sunlight on the great, wide sails. There was the creaking of the ribs as the miraculous device turned. Holding his breath for a moment, he even thought that even the sloshing of the nutrition tanks, where they produced the special substance needed on board, was becoming audible.

Was everything all right? Was everything all right on Alpha and in his head? He could hear his heart flutter, he heard grating sounds produced in the depths of the station. He tried to distinguish which of these sounds had been familiar to him for many years, and which among them might be new. For a moment he convinced himself in his mind that everything on board the ring was all right. As he folded back the blanket, even the sweat seemed dry.

But there was something in him which warned. It seemed to him that his reason was searching for something which, in those dark hours, had escaped his consciousness, as far as it could be considered an alert monitoring organ. He succumbed to the urgent notion that his thoughts - those fine, intensifying instruments roaming about in his brain - had not yet pressed forward to that point which, in its concentration, could be called the truth.

His head still reeling from the things which had driven him that night, the doctor groped for his glasses on the night table. Then, as if in this way he would better be able to fathom the problem, he switched on the light in his sleeping cabin. Now he was as if blinded, and had to blink. As the lamp flared up his mute thoughts glided away, and, since he did not know exactly what he was looking for, he got up with a deceptive feeling of security - as we shall see.

It was two o’clock in the morning, normal and board-time. He donned his robe and slippers and rejected the idea of putting on the space suit, which hung in the adjacent corridor, over them. He stepped out into the hall outside his apartment. Dreams and tossing in bed had made him unsteady on his legs. He strode down the way he always went, without turning on the main lights in the corridor.

From the neighboring cabins the noises of the sleepers emerged: Bobshaw’s snores; the creaking of the metal bed as Cruikshank tossed with formulas. Behind the door which led to Dr. Glanable’s apartment silence reigned. At one of the windows let into the great ring corridor which circled the entire station, Dr. Brownmiller came to a stop. His gaze fell on the Earth.

The place which they were now flying over lay in shadow. The sun was just rising oblique above the curve of the planet and gleamed in the dark brown-tinted glass which now lightened under his hands. It was night down there. Again the scholar had to blink a little. He saw, like shimmering swarms of lights, the big cities which they flew over. There was Cairo, an oasis filled with light in the blackness and silence. In the air still heated from the day, Rome shimmered in the depths.

He thought of how much effort it had cost to heave Alpha into its orbit, and of the many people over whose backs the ring rolled, as it were. He thought he could see the Mediterranean splashing with its blue and black crests in its great basin. He studied the blue and red lights of a station passing far away from them.

Again this shivering overcame him as he thought of his own wheel in the sky. Turning away from the window he looked at the walls of the corridor as if he feared an immediate attack from them. At the same time he had looked about for a weapon. All he found was the fire extinguishers, the picks and the shovels which performed their duty even on board such a modern construction. Again he felt that his hands had grown moist. He went on with almost unnatural calm.

He entered the weak green glow which enveloped the main laboratory. He had gone this way so many times before that he knew every cranny, every corner, every table, even almost every retort - not to mention the computer whose mighty structure filled the laboratory. Almost a bit clumsily - though he had drunk only two glasses of Rhine wine with Bobshaw before nightfall - he walked through the ranks to reach the center of the facility.

He walked along the benches where, for these four researchers and for numerous others who were occasionally invited on board, work-tables were set up. He passed the enormous plastic boards where they had made themselves understood to the others by scribbling the latest discoveries and ideas. Again, wandering through the green glow, he felt as if he had entered an Egyptian tomb. Despite the prosaic nature of the things which took place here, Dr. Brownmiller could not shake off the atmosphere of this room.

There were the glass retorts in which not calves, but human beings were raised. They were arranged in the shape of a horseshoe in the center of the laboratory. Each of them measured about three meters in diameter and in height, space enough to give sufficient scope to the nascent life within. In the cylinders, which tapered toward the top, tubes hung through which the artificial beings fed as if via umbilical cords. The flasks which delivered the nutrient solution glittered on the ceiling.

Without having to turn on the light the scientist could see the yeast which covered the bottom of each retort. In every case a light mist hung over it - as if the newly-created beings lived out their lives in an overcast November day. The white curtain fogged the windows, obstructing the view inside. Beneath the bottles, hanging out of their frames, there were electrical wires by means of which the growth of the incubating forms was regulated. What, the doctor thought, could be the significance of the artificial fertilization of human beings outside of the mother’s body? And what did it mean to be capable of manipulating the genome? Compared with the raising of artificial human beings outside any natural environment, in those glass cylinders in which even the artificial heartbeats of a mother were pulsed into the forming clumps of yeast so that every one of the new beings would develop straight, erect and clean.

This alone, Brownmiller’s thoughts slid along, was the way in which man could free himself from the fetters of nature. This alone was the hammer which would drive progress forward. This was the path, the passage out of the chains with which Nature had shackled the crown of creation. In these first retorts produced in the entire world, there lay further development and hope. But also, his reflections sped, in these bulging vessels the names of the researchers who carried out this project - his name foremost - would be inscribed in the memory of humanity as if with hammer blows.

He had routinely measured the growth of the parallel cultures which were taking form so resplendent and straight. The still-formless clots on the bottom of the vessels were five boys and five girls. For a moment Dr. Brownmiller stood moved and silent, deaf even to his own breathing. But then he thought he heard not only the pulsing with which the oscillator pumped the nutrient fluid into the retorts, but a more intense humming which originated in the inner ear, which now began again with a nervous fluttering - and which, he realized, came from himself.

As if someone had seized him, the man of forty years, by the nape of the neck and were trying to squeeze out his brain, he stepped back, cowering, from the ten flasks in which the white smoke moved as if lungs breathed it out. This was the first of his strange nights, of which he told nothing to his colleagues, just as they told him nothing of theirs. At the door, as he left quietly on slippered feet, he was overcome by the compulsion to turn off the light which was not burning. The green twilight at his heels, he was taken in by the corridor, where after a while the noises produced by the sleepers welcomed him once again - save for the echo of Dr. Glanable.

*

The HOUND plunged toward the Alpha station like a clump of material within which opposing forces are battling. It was as if it were irresistibly drawn by its target while another undetermined impulse drove it away from the slaughterhouse. Now, with the mighty shine of a yellow flame which it threw before it, it seemed as if the downward speed had increased too drastically, or as if the power of the brakes had been overestimated by the computer, so that the projectile (inside which the crew was shaken by fear and panic several seconds long) would shatter against the hub and the spokes.

Since, after all, the calculations were correct as ever, it grew somewhat calmer on board. Then the alarm indicating an object outside sped through the metal hull. In this hull, of course, the men already lay tensely at their posts, already with their weapons almost in their hands, for they did not know what awaited them - all their senses strained and ready to react at a second’s notice. An object which could actually have been overlooked stretched, sprawled, twisted in space. It had almost been steamrollered in the airless sphere in which the braking jets of the rocket nearly grazed it like the last hot light of a dying star.

It almost seemed as if the HOUND enveloped itself in a cloak which now shimmered yellow, now blue, for the computer projected an additional wreath of radiation in order to throttle the speed further. With the rising of this second sun they caught him from the front (the camera looked directly down at him) - the man floating in space in front of the station. He had, from all that could be seen, strapped himself into a protective suit and now stared up into space and into the lens with wide-open, bloodshot eyes, spinning slowly far ahead of Alpha’s passenger lock.

The shuttle moved down sluggishly. The figure which the camera threw onto the main screen and fixed implacably now rocked in space with a completely slack face, in which one could see at most the hint of a twitch. Now he was looking up. They studied him and tried in vain to recognize the familiar face of Brownmiller, Cruikshank, Bobshaw or Glanable. In the slack, pale face, on which hectic red spots swam, the lips twitched. Surely centuries ago the wearer of the face had already been bored under the stars. Yes, his face now had an expression as if the man (now identified as number seven) was drifting like a tourist along the waves of a Mediterranean beach.

Although jets were attached to his space suit he did not move, did not even make the attempt to flee. With a laxness bordering on madness he watched the ship glide down and stop close above him like a gigantic shark observing a diver who inexplicably begins to expose himself. Yes, the form floated in space swaying and relaxed, as if the events around it and in the universe did not interest it in the least, as if it had already everything which it was able to learn of the world. It hung flat in the empty nothingness with a vast, challenging tranquility. This was so terrible that the men in the HOUND winced, that they nearly felt drawn outside into the vast expanses - for in its attitude the body drifting in space called into question everything they thought, everything they felt, everything they considered right.

The appearance had been deceptive. They believed, Scott at their head, that they would have an easy time of it with him. But they were as careful as ever (perhaps also mindful of the fright which tossed in their minds in the face of this challenge outside) as the hatchway opened and two of their men floated out in space suits. For the two had hardly left the opening when the man under the stars seemed to wake up, movement came into him, he produced a silver-gleaming ray gun, which he must have obtained somewhere on board the station and which he now pulled out of a side pocket.

They, of course, - that was what they were trained, indeed, made for - reacted faster. Hardly had he lifted the matter destroyer, used by every space sentry for investigations outside the station as well, in a slack, negligent hand, with an infinitely playful gesture, than a cool, blue shimmer reached out from the lock over him, enclosing and enveloping him. That was a paralyzing ray, which froze his movements at once, which supercooled everything which he represented in the blink of an eye and reduced his brain to apparently merely external reflexes. They wanted him in their control in order to ask him what he had intended there; what he thought; what had happened on board Alpha from his perspective. They meant to penetrate the perhaps shadowy realm of his thoughts with language, as far as possible, to make contact to the greatest extent possible. Those were their intentions and considerations as they laid that blue paralyzing cloud about him and pulled him, within it, on board the shuttle.

*

They lay in their retorts, five men and five women, virginal and rosy, twisting above the culture-medium in the great glass vessels, floating up in the necks as if they wanted to suck to the last drops what the nectar would give. With skin like that of tender infants who have been powdered and anointed; fresh from a steam bath in which they had been forced to tarry, overheated; thus they hung there with sightless eyes - blank pages where the lightning of knowledge had not yet struck.

Dr. Brownmiller was satisfied. He tugged at his golden eyeglasses, quite contrary to his habit, when he felt sure of something. The green light which bathed the central laboratory threw a ghostly shimmer on his fingers and his features and over the three other researchers who had gathered around the console from which, in the next moment, the sparks of knowledge would fly. Dr. Brownmiller ran a flat, now sweating hand over the frame of the energy dispenser.

He said, “It looks good.”

Bobshaw cleared his throat.

“The cameras are running”, he made himself heard.

A hundred times already human streams of consciousness had been transmitted to other similar brains. But never had the impulses used for the Alpha creatures been drawn from the skulls of such a select company as that stored in the matrices. And never had the recipients of the information drawn from the heads of the best of the human race been so perfectly guarded, monitored, protected as these grown-up, innocent children in whom so much hope was now invested.

There seemed to be a slight tremble in Brownmiller’s hand as he pressed the buttons in the given sequence. A rumbling rose from the console as if heavy machinery were starting up. From the necks of the ten vessels thin whip-like wires hung down to the skulls, embracing them with a thousand spidery fingers. A blue light had sprung up around the cords and around the enormous, rosy people magnified by the thick glass. At the same time the console, the vessels, the floor began to vibrate so that even the test-tubes in distant cabinets moved.

The light in the wires grew brighter. The tone of the machine sank deeper, as if gliding under its structure - as if this were the only way to creep into things effectively. On the screen, which also glowed softly with that pale blue radiance, the schematic, heavily stylized cross-section of one of the brains appeared. As if the thin pages of a thick book were being turned, the data sank into the blank, innocent head and the gray, yielding mass. They thrust themselves into this skull - the material particles which cause human thought. They trickled down into the memories according to an unerring technique which collected in seconds what had accumulated in years and centuries.

Despite the numerous attempts which had preceded this experiment, there had been initial disputes as to how much information would have to penetrate the brains before the quantity would first cause the metamorphosis into the quality of a new consciousness. This dispute, which for many years had been carried out in the literature as well, was settled in a few short minutes. Namely, at this point the enormous, rosy human beings began, as if at a secret signal, to move and to stretch. Like mighty giants they stretched their limbs, let out mighty yawns.

Then, as the apparatus continued to deposit the silvery, gleaming pearls in their heads, first one of the girls - two months old, in reality eighteen years - opened her eyes. The dull, dark pupils began to fill with light. A smile passed across her ruddy, slightly wrinkled face; she was amazed at the world which opened up before her. Then two of the young men opened their eyes and stared in surprise from their crystal cylinders. Then it was the girls again, who now looked sideways at the naked young men too.

If one observes the procedure in slow motion - in order to disentangle the many strands which had been tied together with great speed - it becomes clear that the machine had supplied the heads with a new quality of knowledge which went on to pump them with immeasurable additional information. But, as a matter of fact, it was not the case that any of the new human beings could have reached an agreement with the others. Rather, the unfiltered, uninhibited processes in their skulls took place nearly simultaneously - thus too the process of the realization of their own nature and growth, insofar as they could understand it (of course, some care had been taken with the selection of the information), the realization which now lit up like a dark ray in the eyes of the one who, by a few seconds, had been the first to arrive.

Still the enormous children rested in their healthy, sheltered sleep. The processor had just raised them from clumps of yeast to consciousness. Now, as if they were covering years in seconds, wrinkles and lines appeared in their rosy faces. The radiance of innocence in which they placed their thumbs in their mouths had vanished. Their features grew hard, wrinkles etched themselves down from the corners of their mouths. Now one could see how, for the first time, they attempted to clench their hands into fists - young men and young women alike.

Although the scientists were provided with all the information and had gone over the eventualities in their minds - who could have demanded of them, in all seriousness, that they should have been able to grasp every detail of the course of events which from now on came thick and fast. Rather it is certain that each of them grasped one or the other aspect of what occurred. But it is equally clear that in all these points of view the coalescence into the entire picture, soon to emerge, was missing. The ten cylinders burst almost in the same second. Bleeding externally, the ten, without previous agreement, without glancing and squinting, stepped out of the rumbling of the machine. They emerged from their crystal incubators with a terrible flowing motion, with now-hooked hands. Their bodies glided supply, as if their newly awakened consciousness lubricated all the movements of their bodies.

With the bursting of the cylinders, with the glass clattering across the ground, a roaring, a shrill shrieking had broken out in the central laboratory, produced in the inexperienced larynxes, as if the new human beings had conspired to cry out the appropriate form of greeting to the world. Amidst this roaring and groaning one could hear the cries of the researchers - first Brownmiller’s, the first to grasp what was going on, then Bobshaw’s, then the other two.

As if pushed back by powerful anti-magnets Brownmiller and Cruikshank fell back; their bodies were as if epileptic. They collided with the shelves - Bobshaw (whom the creatures had grasped with six, seven arms simultaneously) with white face, with fluttering pulse, whose racing heart, and not only this - quickly and as if there were steel in their virginal fingers - they tore from his chest. His life-sap spurted high, mixing with the bleeding bodies of the new human beings.

The panic was great as the other three researchers, who had stood somewhat further away, fled from the laboratory after the first onslaught of the fresh beings. Yes, the impression upon their brains was powerful; the velvet hammer with which the creatures, in only their first appearance, had swung above them had struck so deeply into their psyches. Thus none of them thought to close the lock behind them - the insurmountable bulwark, the absolutely secure latch. Instead they were like wavering leaves swept down the corridors and halls of a brightly shining station by a hot breath.

*

The entry into the spokes, the blasting away of the bolts which secured the freight lock, became - although the crew members of the HOUND knew that the events on board Alpha were more or less finished - a test of nerves. When they had finally entered the loading dock of the station nearly all had sweat on their hands and in their armpits, yet the tension which had built up seemed to dissolve in the empty cargo compartment.

They divided into two groups, one of which was to stay for an emergency start on board the smaller ship, while the other left under Scott’s leadership to investigate the ring. The bulkhead which connected the provision wing to the main corridor, was blocked. They melted the massive doors and found behind them the corpse of one of the men who had emerged from the glass retorts. His mouth was twisted as if he had cried something out. A strange radiance came from his wide-open eyes, as if even in death he were preoccupied by all the riddles which had remained unsolved for him.

They removed the body to a blue bell-glass. The second body which they found lay in the corridor just around the corner. The cadaver had been deposited in one of the waste containers there. This, which also contained slightly radioactive materials, must have drastically accelerated the process of decay. The flesh had a violet shimmer and was already falling from the bones. The face had a yellow tinge, the eyes were hollow, and it looked as if this man were weeping.

On the way to the headquarters and the laboratory stages they passed a half-opened door which led to one of the apartments. A nameplate showed that this was Cruikshank’s living quarters. As they entered, following a strange smell which hung even in the hall, they crossed a vestibule whose walls were spattered with blood. In the living room the furniture lay in ruins. The pictures had been torn from the walls. The carpet, which had been ripped from the floor, lay in tatters on which blood and the remains of fingernails adhered.

Everywhere in Cruikshank’s quarters hung the stench of decay. Carefully and watchfully they entered the bedroom. Here too the floor-covering had been torn in the same manner as in the living room, the overturned bed had also been smashed to smithereens. Only a large metal wardrobe which stood against the wall had escaped destruction. They broke open the wardrobe and held Cruikshank, who fell toward them, in their arms. The scientist had been roasted. If it had not been for the nameplate on the door of the apartment, there would have been doubt as to his identity.

Brownly - in carelessness or shock - let a film reel slip out of his hands. As he knelt down to retrieve it from the remnants of the carpet he discovered one of the creatures deep under the remains of the bed. The man - his face was tarnished blue, his tongue hung swollen between his lips - lay on his back. Even in death he raised his hands as if he wanted to reach out for someone.

The central laboratory was completely ransacked, all the vessels shattered. All the shelves, retorts, test tubes seemed to have been destroyed. Even the most inaccessible parts of the computer were bent out of shape. Beside the computer lay a strange couple. The man and the woman - both once rosy - hugged each other close as if they wanted squeeze the air out of each other’s bodies. Their faces were desolate, in their eyes reigned an empty shimmer - as if in this vehement clinch they were seeking something whose essence they did not know themselves. Their embrace was so intense that they had to be pried apart with a rod.

*

From one moment to the next the station had changed for Dr. Glanable. Where it had been network of steel girders and plastic, now it seemed to have dissolved into a molten housing, a sticky container. The transition had passed through the doctor’s brain as swiftly as a breath of wind. Though still mentally collected, the yielding mass in his brain had been shaken by the impact.

The metal of the satellite was a cape which laid itself about the scientist. The cloak pressed him heavily to the ground. Night fell, in it the stars could be seen. In a harsh light they stood in front of the window. Dr. Glanable closed his eyes, as if blinded. Then he sensed - as the lines themselves bored through his closed eyelids - that something which he had always known crept up in him.

Like a newborn he had stepped out into the world. He stretched his rosy fingers. When he reached about him, groping, his hand found something soft, warm, whose temperature was the same as his. In this moment his head began to move. At the same time the lamp went on with a reddish, twilight shimmer. Glanable’s jaws were heavy clumps of lead. With infinite effort he raised his lids. He stared into the twilight.

As he turned his head he saw a woman, naked and rosy, laying beside him. An idiotic, uncomprehending grin now glided across her face. An empty look passed from her to him. Then the doctor noticed - though as if bound in shrouds - how the fresh, virginal creature raised first one, then the other hand - to reach for him.

*

They had collected and sorted the corpses, layered them in glass containers in which they could be preserved. They sorted the shattered creatures from the bruised. Those whose spine had been broken were separated from those whose consciousness had been pulled from their heads as if on strings. The search troop even found individual shattered bones in the depths of the station. The wheel was one great slaughterhouse, its floors smeared with blood. In the weightless corridors which lay in the center of the ring it floated in the air as tiny red drops.

One of these corpses they hesitated - as if struck by awe - to lay upon the pile of the other bodies. They found this man, his life extinguished, while inspecting the store-room. At the entrance to the depot where iron ore and other non-radioactive materials were stored, a small pool of blood collected under the door. Even before they were able to open the door the fluid was dark and congealed.

At first, as the door swung open, Scott, who went first, did not see the dead man at all. But perhaps he noticed him - in the corner of his eye, so to speak -, but then his consciousness recoiled from the sight which he could not bear alone. As always. As he hesitated the captain was pushed forward by the following men. Then a confusion arose among the members of the search troop. It was as if they knew, below the threshold of their consciousness, that it would be advisable and opportune to turn around, look around, to turn their heads and look into the eyes of the man who hung above the wall. But that is easier said than done, even for fighters who are used to moving through streams of blood.

Thus, after seconds had passed, one of them finally withstood the pressure. Then, encouraged, all eyes fell on the tall, imposing man who had been affixed to the wall perhaps two meters from the ground. Although his arms were now half raised above the shoulders, his powerful muscles still seemed to play. Of all the human beings plucked from the retorts, this one surely had to be judged the most successful.

Despite the strength which could vividly be sensed in his body, his angled elbows now seemed frail - rigor mortis, after he had hung there as if for thousands of years, had spread through his entire body. His limbs, his entire body was waxen, translucent - so that it seemed that through him one could study every detail of the wall on which he hung.

The hands were hooked like claws. Through the palms metal bolts had been driven with a drilling-machine which lay below him. His feet had welded on with exactly the same staples, so crooked and skewed that it looked as if he would twist his body away in the next moment. As the creature sagged down from the wall, his head lay to the side. The eyes were open. It was these bright and clear pupils whose gaze, even now, in death, burned in an unnatural fire.

While the search troop hesitated, cold entered the room. They shivered and shook themselves a little. It seemed that ice collected between them, creaking. Never before, Scott thought, had he encountered a person whose eyes gazed so bright and clear even in death - in which, despite the suffering which suffused his features, such an unheard of flame burned. It could literally be grasped what a highly-developed consciousness had once blazed behind this brow. This man’s unerring and pure will seemed to reach out to one, even now. At the same time, beneath all the pain which their torture had caused, a strange goodness lay, a friendly shimmer - that after death he would bear no malice even toward those who had opened his side with the welding torch.

For a moment the captain wondered why they had had to kill none other than this more clear-sighted, this cleanest, this friendliest man in the most cruel manner which they could remember. Was it the implacable will delineated in his temples? Perhaps the clear consciousness which only death could diminish? Or had his most cruel end brought about a sharp insight into things - through those eyes, now merciless as well, which would not flinch from the truth by a millimeter.

There was still a trembling in the men as they stood before the corpse. One attempted a joke with a hoarse voice, but that did not break the spell. Then finally - after the champions had swayed a little, like grain on the field, as if a wind had sprung up - Scott and the others regained enough courage to dare to take the man from the wall with a degree of secrecy and bed him with the other corpses, where for some time he shone as if from within.

*

In Dr. Brownmiller, the head of the project, a world had collapsed as if beneath heavy, silent hammer blows, as the flood of rosy bodies burst from their cylinders. He - himself a leaf whirled away by the wind - ran through the cold, bare corridors of Alpha which, like the calculations in his head, had lost their stability, while his consciousness had slid into the depths and was pulled down as if by magnets. In the moment of his greatest triumph Dr. Brownmiller was destroyed.

It is difficult to imagine what happened in these moments when the world lost its certainty for the supervisor of the experiment. If one follows his thoughts as far as possible (without oneself becoming entangled in his labyrinth of madness), like him, one loses one’s orientation from one moment to the next. For the life of him he could no longer tell what part of the spoke he was in, seconds after his reason collapsed. No matter: since his magnet-equipped feet continued to carry him he had not yet been reduced to the state of a babbling infant, he was still able to control certain of his bodily functions. And how, as if a bad joke were being played on him, that part of his rational thoughts (albeit now somewhat scattered by the wind) with which he had worked on the Alpha Project still functioned.

He walked crunching through steel and plastic. In the sleep which he may have found now and then he ground his teeth as the nightmares rose. Let us assume that he walked through one of the melting walls. This speculation is as good as any other. Let us presume, for the moment, that in his mind he went through the calculations, that he checked them column by column. In his mind’s eye rose the data for growth, the mixture of the proteins, the values of the nutrient solution, the number of the electrical impulses - in the hectic stream of his thoughts he was satisfied with all of them.

Where, then, was the error? What had nonetheless driven the experiment - which had seemed so safe, a calculation seemingly without risk - into those depths of the catastrophe which had erupted so bloodily? Since after all, without a doubt, the feeding of the artificial beings, reducing their maturation process to two months, had been right? For one, two seconds Dr. Brownmiller had regained the iron certainty which distinguished him, his reflections once again ran on smooth paths, once again he knew his name, where he was going, what this experiment was about.

He found himself in a corner of the corridor whose floodgates had burst. He cowered down with bloody hands, with torn lips, full of pains which raced through his body. Fear had driven him to his feet, for now they came around the corner, the men and women with the torches, armed with picks and shovels, looking for him. He could hear that they saw him, their roaring, the shrieking of the rosy women. First the men, then the girls began to run as they saw their target. His thoughts wavered again as he saw how fiercely they desired to come to him.

He escaped them, his body mobilizing all its forces, and they collided, sick with disappointment, against the walls of the corridor. His thoughts still sought an explanation for the catastrophe, they drove Dr. Brownmiller instinctively to the nutrient tanks. The water into which he waded, splashing, was heavy. It held him up as he vainly attempted to sink. There he swam, caught helpless in the broth.

As he gulped the vital solution, his reflections returned once again to the progress and results of the experiment. But what, a clear thought crossed his mind, could have gone wrong in this endeavor when the liquid food, as he could now see for himself, was in order? Now half sinking, the skulls in which the blue lightning struck dangled before him. Once again he probed the dawn of knowledge, the beginning of comprehension, when the virginal brains were filled with that immense mass of information.

How much time had he and his colleagues given the creatures really to cope with the information which they had been forced to absorb in seconds? His consciousness waning, the doctor began to realize that he and his colleagues had deluged these innocent, these fresh beings with a flood of data against which they had not been able to develop a defensive screen, no blockade or filter - nothing to protect them from the onslaught of knowledge. That was what had happened! The untouched creatures had been overburdened, without the slightest chance to find their way in the world. Whatever motives and associations had flooded these heads - they had had to take it seriously, had to take it for reality. And what an insane, torn society it was which now, unchecked and unfiltered, swept the new human beings along with it!

As if behind a veil, as if a murmur had settled over his ears, over his thought, the doors which led to the nutrition tanks burst open. The supervisor of the project still swam atop the broth, unable to summon enough energy and will to flee the container. Thus they found him at last - the intellectual fly which they skimmed like a drop of fat from cream, to pull him out of the trough, to pump out the liquid which had permeated him, to rub him down, indeed, perhaps even to revive him mentally so that he would survive long enough for their terrible revenge.

*

He was a broad, heavy man, who - standing at the window and looking over a bullneck at the street - folded his arms behind his back. He wore a brown pinstriped suit, and, seen from the front, a silver necktie. What he, Hurwicz, the Minister of Research, saw below on the street was the traffic of the capital which unfolded at noon.

He had read the dossier regarding Alpha, and Scott’s report. He knew of the drama which had been acted out high above their heads. And, still staring down at the highway, he reviewed once more the thoughts which he wanted to present to the President. He had made himself a clear picture of the massacre on board the station. The reasons why this most top secret governmental project had been doomed to failure remained open. Dr. Brownmiller’s corpse, which the beasts had torn to pieces, had vanished.

But Scott did not know everything. The truth for whose sake Alpha had been set into operation lay deeper. It was not only that they had attempted in this way to man an expedition to the stars - overcoming the problem of the long journey by producing the crew at the destination. The main idea which had led to this experiment was its military application. For an impending war it was an incredible advantage to be able to produce human material at will.

But even that was not all. It had also been considered that a larger number of bodies and body parts could be used in medical research. Hurwicz moved his lips silently. Below he saw a newspaper boy who loudly called out the false headlines. How did it go? Unparalleled catastrophe in space! Four prominent scientists annihilated! Progress in the nutrition of humanity, an upswing regarding their bodies! Only a minor psychic disturbance, from which the first imperfect test subjects had suffered, needed to be eliminated before the path into the future could be smoothed.

Hurwicz stepped back a little from the window. Then the bell rang. The Minister braced his back. He felt secure within the protection of his thoughts. In him was the comforting feeling - when he thought, shuddering, of the creatures and of the films which he had seen of them - that he had built ramparts around his consciousness sufficient to stand up to anything with which the President might deluge him. Thus, having matured and grown with his defense mechanisms all these years, Hurwicz, the Minister of Research, walked through the door behind which his President awaited him.

THE NEW HUMANS

The apartment Dr. Glanable entered had a spacious corridor which was now filled with policemen. Most of them were young men, illgroomed and unkempt, clutching their machine guns as if seeking a hold. Crossen, the police officer who had led the operation, waved Glanable down the hall. In passing Glanable sensed how these young policemen dressed in leather jackets had sweated out their fear.

Several doors led from the corridor, some of them ajar, some of them shut. The doors at the end were wide open. Even as he approached, Glanable could see that the door in which Crossen stood led to the bedroom. Crossen crossed the threshold. Glanable followed him, pushing past a young policeman. He surveyed the bedroom with a single glance, the big wardrobe with the mirror in the middle, the window with the billowing curtains, and a bed below the window, a bed like a wide lawn, at the foot of which one could see a portable television set and from which a police reporter with cameras and batteries hanging around his neck and two policemen had just stepped back.

On the bed lay two naked forms wrapped in summery sheets, sprawled chaotically across the bed as if in panic. There was a man, who lay face-down, and a girl, half-turned away from him, as if in an attempt to flee. Glanable knew the girl. It was one of the girls Maren had kidnapped from the glass retorts. Maren’s back could be seen. It had been opened by a spray of shots which must have come from a machine gun. Maren’s left arm hung over the edge, the other was raised to the pillow as if he had wanted to drag himself up to the window before the bullets hit him.

Glanable could see the girl’s eyes. They were wide open, and they seemed to stare at an event which they absolutely could not understand. Her face was waxen. A dark-red trickle, already congealed, ran down her chin. The blood of both could be seen all over the bed and on the brown carpeting. It seemed to have been spilled by the bucket. Glanable looked in vain for signs that the two had been armed.

Glanable went around the bed. He knelt down next to Maren’s body. He examined his face from the side. Maren’s mouth was open, as if he had cried something out in his final moments. One wide eye, which stared glassily across the carpet, had an expression of horror and panic. Glanable was unable to prevent a slight flush from creeping up his neck. Crossen noticed Glanable’s emotion and said a few regretful words, emphasizing that his officers had acted in selfdefense. Glanable nodded as he went out, his dead creatures behind him.

It had been the government’s idea, the attempt to produce such artificial creatures in retorts. Unlike previous medical experiments, it was not a question of incubating the fertilized egg outside the mother’s body or simply performing the fertilization there; they had proceeded on the assumption that it must be possible to use a new substance, a rapid catalyst, to speed the growth process of the human body, the nine months and the many years, to a few months by means of fermentation steering.

A top-secret laboratory had been established in Washington. The core of this laboratory was a closed experimental room with a number of cylindrical retorts. Each of these retorts was about three meters high and wide. The retorts narrowed at the top, tapering away to a pear shape. A tangle of cables, coils and wires led to each retort, as well as tubes dripping the nutrient solution which was kept in containers under the ceiling.

They were already experienced enough in genetic manipulation to control the growth of the artificial human from the beginning to the end, using matrices which emitted impulses into an artificial yeast. The control was taken over by a computer which filled half the laboratory. The point of the experiment - and this was why it was kept top-secret - was to produce new human material quickly and in whatever quantities desired. Since the experiment flew in the face of all the ethical principles in which humanity had ever believed, it had to be carried out in secret. It was also clear that this immeasurable advantage, as far as human material was concerned, could not be allowed to fall into the hands of the enemy in the event of war.

Glanable and his co-workers were very satisfied with the initial growth rates. After only a few hours one could watch the artificial creatures forming in the yeast at the bottom of the containers. They ran through all the stations of human development quickly, as if in fast-forward. The thumping of the artificial heartbeat could be heard through the glass walls. The cylinder was regularly tilted and rocked, the air, pressure and temperature were altered to provide the emerging life with a normal development.

After two weeks it came time for the new humans to be born. The umbilical cords were cut, and a new apparatus made it possible for them to feed themselves by way of simple reflexes which they had already learned. Though they became larger day by day, growing visibly, their life was not all that different from that of helpless babies, who in a certain sense are little more than mere digestive mechanisms.

The critical point of the experiment was the brain of the artificial humans. It had grown along in the process of the artificial maturation while remaining unable to enrich itself with the impulses which accumulate in the course of eighteen years. Thus, after two months and several days, when the phase of physical development came to a close, the girls and young men, some of whom had been bred with impressive physical proportions, were, as far as their mental development was concerned, blank slates on which any given text could be written.

If they had had the intention of making up the mental development of the new humans at the appropriate speed which normal humans require, it would have taken years for the new humans to match their physical state of development mentally as well. This would also have meant that the temporal advantage, which after all was the entire point of the growth rates of the new humans, would have been lost again.

Thus a procedure had been developed whereby a complicated dream machine was to transfer the consciousness of outstanding people into the artificial humans. The problem was that though the machine was able to transfer individual pieces and bundles of information, it was incapable of creating the cross-references and associations which the brain must produce itself.

The dream machine had been loaded with two different programs, one for the three young men, one for the girls, so that, if the experiment succeeded, they would be completely similar mentally, which was an entirely desirable outcome, considering the military purpose of the experiment. The thoughts were loaded by way of a control desk coupled to a computer. On a control monitor the process whereby the silky-soft matrices were leafed into the brains of the nine humans could be observed. One could look into the brains of the new humans, as it were, though on the screen they were colored to make them easier to distinguish.

Due to the large capacity of the dream machine, a period of about two hours was scheduled for the process of organizing the consciousness. Naturally, the brains were built up from below, starting from the brain-stem, from the sense of smell, from the feelings and emotions. Looking at the young humans, one could see the effect which the process of their own development of consciousness had on them. Almost simultaneously they began to grope along their naked, virginal, rosy bodies. Just now with their thumbs in their mouths, they had set out to explore their immediate environment. They did this with closed eyes. But even as they now opened their eyes, hesitantly, blinking, one began to see certain differences. A young man in the right-hand retort, whose movements had been very slow as he felt his body, hesitant, as if he did not believe in himself, opened his eyes only halfway, and his eyeballs blurred immediately. And the machine overrode him, as it were, forcing more impressions into him even after he sank down to the bottom of the retort. Each new impulse which entered his head seemed to pull him up slightly, but at each lull in information he collapsed again.

The other two young men developed splendidly at first. They opened their eyes wide, as if to discover the world for themselves. Though at first the expression in their eyes was dull and blurred, and though their lenses had to adapt to their surroundings first, now it became increasingly sharp and precise; as one could see from their eyes, they began to perceive even the glass retorts in which they were held captive as their surroundings, at the same time with the indication that they would soon leave their prison.

The young man in the middle seemed to be furthest along. His face was quite fresh and rosy. His eyes gleamed. He gave the impression of an eager pupil who races through the material with enormous strides, growing conscious of the progress he is making. To look at his face, especially his eyes, he resembled a one-way street along which one could drive unerringly and with increasing speed. He had already grown so strong and certain that one could think that at any moment he would attempt to leave the glass retort.

At this point a shadow crossed his face, as if a cloud had darkened the laboratory. His eyes, which just now had seen the world as if it was always radiant, flickered. It actually seemed as if the light which shone from within was wavering in its brightness. An enigmatic expression entered his eyes. It was as if all the unanswered questions in the world gathered in his mind, as if he, of all people, had to answer them.

He opened his mouth as if to speak for the first time. But though his ability to speak should have been fully developed, nothing but a dry croak came from his throat. Now he began to babble. He raised his hand to his throat. Then it was as if an enormous fist had appeared out of nowhere and struck at him, as if it had passed over his head, as if it were erasing his brain. Now his face was a contorted mask. The fires outshone each other in his eyes.

He began to twitch. It was as if his arms no longer belonged to him. The attempt to stand on his trembling legs was in vain. His body lay twitching on the floor. He foamed at the mouth. Although the glass in which they were all imprisoned muffled the sound, one could hear his raging and crying as if he wanted to reach the world far outside. At this point Glanable had already turned off the machine which ran this first young man.

Before we turn to the third young man, let us look at the three girls. Whatever the two young men may have gone through, the girls were better off, from the point of view of the course of the experiment. All three of them were sweet, gentle beings suffused with a somewhat old-fashioned program. Society might have been in a period of transition, but for the purposes of the experiment it was considered more practical to assign the girls a more humble, subservient role, wherein their main duty consisted of pleasing the men and performing all work without complaint.

And thus they had developed in the retorts. Before they had been beautiful shells, pretty masks, completely without consciousness, but now they blossomed in the constant stream of information. What their bodies alone could not give them was given to them by the purity of their thoughts, was given to them by the fire with which consciousness filled their bodies. They covered their nakedness fearfully, gazing out of the retorts with provocative gazes, without having seen the results of the development in the other two retorts.

The boy in the left-hand retort, Maren, had gone through a development similar to that of the other two men, who were already finished. He too had felt his body. He too had breathed in the scent which had been blown into his retort. He too had opened his eyes, first somewhat hesitantly, then with increasing eagerness. As he learned, his face, too, was confident and radiant. However, at the point when he too had been thrown into confusion, he began to develop differently than his neighbors.

The dream machine went on running in him as well. It may be that a few modicums of additional information reached his consciousness before the confusion began. No matter. He staggered visibly. The force of the thoughts which raced behind his brow nearly struck him down. But though he lurched, he did not fall. On the contrary, his body had raised itself to its greatest height. There he stood in the middle of his retort, with flashing, bitter eyes. A moment later he tore the wires which connected him to the dream machine from his head and used the steel crown which had just lain around his head as a weapon to shatter the glass cylinder.

The scientists flinched back as the glass of Maren’s retort shattered around them. Sheer incomprehension could be seen in their white faces. A few stifled cries could be heard, but they fell silent at the sight of the - yes, of what? the monster? the abnormal human? the Frankenstein which stepped out of the retort? Unprepared for this eventuality, they gave the monster a moment’s advantage.

But there also seemed to be something in Maren’s posture, in his gestures, in his gaze, which commanded respect, esteem, even submission. It was as if he had balanced his consciousness on one point, as if he had pulled together all ideas to one single idea, as if he had taken a few still purposeless steps through the laboratory for the sheer sake of action, from sheer will. The completely naked man, still rosy, still gleaming from the efforts behind him, holding the steel ring with which he had shattered the retort, planted his feet like a striding king.

Then he looked at them almost at the same time, with a terrible, roving gaze, restless and yet clear and full of depth in which the information which he now gathered ran down as if to the bottom of a deep lake. With this one look he seemed to judge them once more, what he was to think of them, seemed to assure himself of what he already knew and what he had figured out in his brief life. Up to this point no one had gotten it into his head to stop Maren.

The scientists’ paralysis at Maren’s confident, determined posture still had not passed when the artificial human, in a second, terrible gesture, shattered one of the retorts holding the girls. As if the soles of his feet had grown insensitive from long practice, through autosuggestion, he walked through the shards of glass and pulled the girl out of the remains of the retort.

Then, with the girl at his side, he reconsidered. Like a small child he climbed onto one of the tables of the computer console and armed himself with a sharp tool he found there. Now for the first time the people who stood about, unable to grasp the miracle which had occurred, began to move. Maren, grabbing the girl again, stopped this movement with a single gesture.