9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

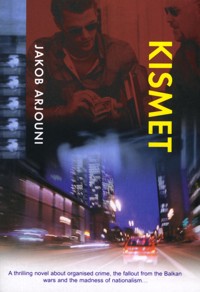

It all began with a favour. Kayankaya and Slibulsky had wanted to help out Romario, the owner of a small Brazilian restaurant, when he is threatened by extortionists. Then suddenly there were two bodies on the floor of Romario's restaurant, their faces caked in white powder. Kayankaya is troubled by these deaths and decides to find out who the men are, until he himself is pursued by a mafia organisation about whom nothing appears to be known. Gradually it becomes clear to Kayankaya that he is facing the most brutal and dangerous group of gangsters to have run Frankfurt's station quarter. And then a new assignment comes in: he is to find a woman he has seen in a video film, and who he is convinced was looking at him from the screen. Kismet is a brilliant novel about organised crime, the fallout from the Balkan wars, and the madness of nationalism from one of Europe's finest crime writers.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

It all began with a favour. Kayankaya and Slibulsky had wanted to help out Romario, the owner of a small Brazilian restaurant, when he is threatened by extortionists. Then suddenly there were two bodies on the floor of Romario’s restaurant, their faces caked in white powder. Kayankaya is troubled by these deaths and decides to find out who the men are, until he himself is pursued by a mafia organisation about whom nothing appears to be known.

Gradually it becomes clear to Kayankaya that he is facing the most brutal and dangerous group of gangsters to have run Frankfurt’s station quarter. And then a new assignment comes in: he is to find a woman he has seen in a video film, and who he is convinced was looking at him from the screen.

Kismet is a brilliant novel about organised crime, the fallout from the Balkan wars, and the madness of nationalism from one of Europe’s finest crime writers.

Jakob Arjouni was only 20 when his first bestselling crime novel was published in Germany and was such a literary prodigy that he had managed to create a substantial and durable body of work by the time of his death in January 2013 at the age of 48. This output includes the five pioneering novels featuring Kemal Kayankaya, a Turkish-German private eye, which began with Happy Birthday, Türke! in 1985. An immediate success, it was filmed by the director Doris Dörrie in 1992 and subsequently published by No Exit in 1995.

The final Kayankaya novel, Brother Kemal, which Arjouni wrote against the terrible knowledge of a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, will be published this summer by No Exit alongside reissues of the earlier books in the series.

Arjouni’s fascination with detective fiction was shaped by external influences. Two of his literary heroes were Raymond Chandler and Georges Simenon. From the American, he took the figure of the private eye as a flawed but honest outsider; from the Belgian, he learned the importance of psychological characterisation.

But while these mentors clearly informed the creation of Kayankaya, with the detective’s status as the son of Turkish immigrants giving a fresh twist to the tradition of the investigator as an odd one out, Arjouni brought to the form an eye for social and historical detail that was entirely his own. Kismet (2001) deals with the consequences in Europe of the Balkan wars, while One Man, One Murder (1992), which won the German Crime Fiction prize, has a background of sex trafficking. Characteristically, the final Kayankaya book explores the limits of free speech and religious tolerance as the private eye protects an author under death threat from Islamists at the Frankfurt book fair.

Born in Frankfurt as Jakob Michelsen (Arjouni was a pseudonym), he had an early literary role model: his father, Hans Günter Michelsen, was a successful dramatist and Jakob wrote a number of early plays before settling on the novel as his preferred form. His father gave him inadvertent but invaluable research for his future crime stories because of a fondness for taking his family to restaurants in an area of the city that was in the process of transition from red-light district to international quarter. Pungently seedy details of the rougher parts of Frankfurt are a particular feature of the Kayankaya books.

While the Kayankaya novels were the basis of his initial reputation and income, they appeared at very wide intervals. Arjouni was prolific between them. Magic Hoffmann (1996) was a story of bohemians in Berlin planning a bank robbery. Chez Max (2009) was generally considered one of the most original and thoughtful fictional responses to 9/11: it was set in a dystopian Europe in 2064, where a fenced-off community hides from terrorism and unrest. The powerful English translation was by his regular interpreter in the UK, Anthea Bell.

Modest, blazingly intelligent and thoughtful, his work both inside the crime genre and beyond it makes Jakob Arjouni a formidable figure in modern German literature

Mark Lawson

noexit.co.uk/jakobarjouni/

Jakob Arjouni: 1964-2013

Praise for Jakob Arjouni

‘It takes an outsider to be a great detective, and Kemal Kayankaya is just that’ – Independent

‘A worthy grandson of Marlowe and Spade’ – Stern

‘Jakob Arjouni writes the best urban thrillers since Raymond Chandler’- Tempo

‘There is hardly another German-speaking writer who is as sure of his milieu as Arjouni is. He draws incredibly vivid pictures of people and their fates in just a few words. He is a master of the sketch – and the caricature – who operates with the most economic of means’ – Die Welt, Berlin

‘Kemal Kayankaya is the ultimate outsider among hard-boiled private eyes’ – Marilyn Stasio, New York Times

‘Arjouni is a master of authentic background descriptions and an original story teller’ – Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung

‘Arjouni tells real-life stories, and they virtually never have a happy ending. He tells them so well, with such flexible dialogue and cleverly maintained tension, that it is impossible to put his books down’ – El País, Madrid

‘His virtuosity, humour and feeling for tension are a ray of hope in literature on the other side of the Rhine’ – Actuel, Paris

‘Jakob Arjouni is good at virtually everything: gripping stories, situational comedy, loving character sketches and apparently coincidental polemic commentary’ – Süddeutsche Zeitung, Munich

‘A genuine storyteller who beguiles his readers without the need of tricks’ – L’Unità, Milan

www.noexit.co.uk

Chapter 1

May 1998

Slibulsky and I were crammed into the china cupboard, emptied for the purpose, of a small Brazilian restaurant on the outskirts of the Frankfurt railway station district, waiting for a couple of racketeers to show up demanding protection money.

The cupboard was about one metre twenty wide and seventy centimetres deep. Neither Slibulsky nor I would be giving the clothing industry cause for concern about the sales of their XL sizes. Furthermore, we were wearing bulletproof vests, and when it came to the crunch we hoped at least to get a pistol and a shotgun into position where we wouldn’t shoot ourselves in the foot or blast our own heads off. I could just imagine the racketeers entering the restaurant, hearing pitiful cries in the corner after a while, and opening the cupboard door to find two total idiots squashed inside, arms and legs flailing helplessly. And I pictured Romario’s face at this sight. Romario was the owner and manager of the Saudade, and he had appealed to me for help.

I’d known Romario since his first gastronomic venture running a snack bar in Sachsenhausen. Until now he’d only been an acquaintance. I was glad to know him when I was skint and he stood me dinner. I wasn’t so glad when I was in funds and met him in a bar and he came to sit at the same table, and we had to talk about something or other just because we knew each other. So if this evening’s operation came into the category of a favour done for a friend, then it was mainly because Romario hadn’t offered me any payment and I couldn’t really ask for any either.

Just after midnight. We’d stationed ourselves here half an hour ago, and for about the last twenty minutes my legs had been going to sleep. It was unusually warm for early May. Daytime temperatures were up to twenty-seven degrees, and by night they didn’t fall below fifteen. Which did not keep Romario from turning his central heating up to maximum – from force of habit and because complaining about the German weather was, in a way, one of his last links with Brazil. He’d lived in Frankfurt for the last twenty years, he went to the Côte d’Azur on holiday, and I didn’t know if overcooked sweet-and-sour chicken and tough pork chops with canned peas were typical specialities of Brazil, but you couldn’t really wish them on his native land. Anyway, the whole city might be going around in T-shirts, his customers might be dying of heat-stroke, but Romario insisted that it was always cold in Germany and the sun always shone in Brazil – whether he was in a generally bad or a generally good mood.

So I wasn’t going to make any money out of this, I couldn’t feel my legs any more, the temperature inside the cupboard was approaching jungle heat, and from time to time I heard this barely audible hissing.

‘Slibulsky?’

‘Hm?’ Brief, unemotional. The sweet he was sucking clicked against his teeth.

‘What did you have for supper?’

‘Supper? What do you mean? Can’t remember.’

‘You don’t remember what was on the plate in front of you a few hours ago?’

He cleared his throat, the way other people might give a little whistle or roll their eyes, indicating that they’ll try to answer your question in friendly tones, but naturally it doesn’t for a moment interest them.

‘Let’s see… oh yes, I know. Cheese. Handkäse. That was it. Gina went shopping this morning and…’

‘Handkäse with onions.’ And you can’t get much smellier than Handkäse anyway.

‘Of course with onions. You don’t eat cheese with strawberries, do you?’

I put a good deal of effort into giving him as contemptuous a glance as I could in the dim light of the cupboard.

‘Didn’t I tell you we’d be spending some time together in this hole?’

‘Yup, I believe you did mention it. Although I remembered the cupboard as kind of larger.’

‘Oh yes? Like how large? I mean, how big does a cupboard have to be for two people, one of whom has just been stuffing himself with onions, to breathe easily inside it?’

In what little light filtered through the keyhole and some cracks in the sides of the cupboard, I saw Slibulsky make a face. ‘I thought we were here to scare off some sort of Mafia characters? With our guns and bulletproof vests, like the good guys we are. But maybe Miss Kayankaya fancies running a hairdressing salon instead of a detective agency?’

What did I say to that? Best ignore it. I told him, ‘I’ve got sweat running down my face and into my mouth, I have a feeling your stink is condensing, and I don’t reckon the good guys have to put up with other people farting.’

Slibulsky chuckled.

Cursing quietly, I bent to look through the keyhole. I could see Romario’s bandaged arm the other side of it. He was sitting at the bar doing something with a calculator and a notepad, as if cashing up for the evening after closing the restaurant. In fact he was too nervous to add up so much as the price of a couple of beers. They’d paid him their first visit a week ago: two strikingly well-dressed young men not much older than twenty-five, waving pistols and a note saying: This is a polite request for your monthly donation of 6,000 DM to the Army of Reason, payable on the first of each month. Thanking you in advance. They didn’t say a word, they just smiled – at least until Romario had read the note, handed it back, and believing, not least in view of the sheer size of the sum, that he was dealing with a couple of novices said, ‘Sorry, I don’t see how I can go along with your request.’

Whereupon they stopped smiling, shoved the barrels of their pistols into his belly, crumpled up the note, stuffed it into Romario’s mouth and forced him to chew and swallow it. Then they wrote Back the day after tomorrow on the bar in black felt pen, and went away.

In spite of this little demonstration, Romario didn’t really take the matter seriously. He’d been running his place here near the railway station too long to panic the first time a couple of young tearaways tried extortion. As everyone knows, the big protection rackets, the ones you have to take seriously, have a whole crowd of small-time con men following in their wake, thinking they might as well give it a try. Like when you’re sixteen you say hey, why not just take a look and see if that bike over there is padlocked.

Romario threw up the note he’d swallowed, knocked two nails into the side of the bar and hung his pistol on them. When they came back they’d see how a real man dealt with such outrageous demands. But they didn’t come in the evening, as he had expected, and Romario wasn’t behind the bar. It was morning, and he was in the kitchen putting meat in a marinade with oil and seasonings when they suddenly turned up. Still smiling, and with another note. Your monthly donation to the Army of Reason is now due. Many thanks for your commitment to this good cause.

When Romario, with the pistols pointing at him and his hands in the marinade, said he didn’t have six thousand marks, just how much profit a month did they think a little place like this made, he might as well close down right away if he paid up, they twisted his arms behind his back, tied him to the radiator, and nipped his thumb off with a pair of pliers. The cleaning lady found Romario lying unconscious in a pool of blood. His thumb was on the bar, with the words Back on Thursday written beside it.

This was Thursday, and the bandage round Romario’s arm looked bright white against the wood-panelled wall. They’d sewn his thumb back on at the hospital. The doctor hadn’t been able to say whether he was likely to keep it, and how much use it would still be if he did. Romario’s explanation that he’d done it chopping onions was received with scepticism, but it had stopped the hospital reporting the incident to the police. Now and then Romario glanced at the china cupboard as if to make sure that we hadn’t disappeared through some crack in it. Whenever he did that I knocked my Beretta quietly against the door to reassure him. Cutting off his thumb was a brutal business and I was sorry about it, no question. I didn’t want to stop and work out whether I was particularly sorry because, but for that injury, a flat-rate payment plus expenses might at least not have been beyond the bounds of possibility.

The hissing sound came again.

‘Slibulsky, you’re an arsehole!’

‘And you’re a fucking queen.’

I sighed. ‘If I was, I expect I’d have hired this cupboard on purpose to be shut up with you and your fragrant aroma.’

‘Oh yeah? The things you know about… is that the way a man starts thinking when he’s gone without a girl-friend so long?’

‘Oh, Slibulsky.’

‘And don’t say “Oh, Slibulsky” every time I mention it. If you ask me…’

‘Quiet!’

A car had drawn up outside. The engine was switched off; doors slammed. Soon afterwards feet climbed the steps, stopped briefly, then there was a knock. Romario rose from the bar stool and went to open the door. I took the safety catch off my pistol. In so far as it was possible in the cupboard, Slibulsky got on his marks as if to run the hundred metres, ready to leap out with his shotgun levelled. Through a second hole in the cupboard, one we had bored on purpose, I saw two young men in cream linen suits coming into the bar in silence. Both had pale, clean-shaven faces and thick fair hair with short back and sides. At first sight they looked as German as the young men on the German Mail advertising posters, so the obvious deduction that they never said a word because they didn’t know any words in German seemed to have been wrong.

One of them handed Romario a note. Romario read it and waved them over to the bar. Black automatics gleamed in their hands. We’d hoped they would leave the pistols in their holsters – now Slibulsky and I would have to delay our appearance until Romario was out of the firing line. Romario knew that.

‘Would you like a drink?’ I heard him ask, his voice trembling slightly. I saw them both shake their heads. One pointed with emphasis to the note in Romario’s hand.

‘Sure, right away. I’d just like to know whether this monthly donation will really settle everything?’

They nodded.

‘And if… well, suppose there’s other organisations asking for, er, donations… I mean, does this payment mean you give me some kind of protection?’

They nodded again and raised their pistols, smiling.

‘Fine, so where do I reach you if I need you?’

One pointed the barrel of his pistol at his ear and his eyes, which probably meant: we know what goes on in this city, no need to call us, we’ll call you.

Where did these characters come from? I knew German, Turkish, Italian, Albanian, Russian and Chinese racketeers who extorted protection money – but speechless racketeers were something new.

‘Okay,’ said Romario, ‘then let’s see about…’

‘Then let’s see about’ was our signal. While Romario flung himself to the floor behind the bar with a single movement, and then crawled towards the kitchen door, Slibulsky and I burst out of the cupboard shouting, ‘Hands up and drop your guns!’

However, they did neither, and if I hadn’t got hold of bulletproof vests for us, that would have been the last mild spring night we ever saw. They fired at once. I felt the bullets hit my chest, threw myself to one side and fired back. We’d agreed in advance to aim at their heads if it came to a shoot-out; after all, we weren’t the only ones who could lay hands on bulletproof vests. I hit one of them under the chin. Blood spurted over his cream suit, he dropped his gun and clutched his neck with both hands as if trying to strangle himself. He swayed briefly, fell backwards and hit the floor. Slibulsky blasted the other man’s forehead away with his shotgun. The wooden panelling was peppered with a hail of shot. While the man who had lost his forehead was still falling I got behind the bar and switched off all the lights.

In the dark I called, ‘Romario!’

‘Here,’ came a voice from the kitchen.

‘Slibulsky?’

‘Oh, shit!’

I went to the window, peered past the curtain at the street and the buildings opposite. No pedestrians, no lights coming on, all quiet. There was stertorous breathing behind me, not very loud.

I snapped my lighter on and bent over the man who was still clutching his neck. Blood was running through his fingers. His large, pale eyes looked at me, bewildered.

‘Who sent you?’ He didn’t react.

‘I can call a doctor or not, as the case may be. I want your boss’s name!’

But he couldn’t hear me any more. His hands dropped from his neck, his head fell to one side, and he made one last choking, gurgling sound. Then there was nothing to be heard but the hiss of my lighter. The flame cast a yellow light on the dead man’s face. It was made up, or anyway powdered, that’s why it had looked so pale just now. The skin was darker on the ears and the ragged remains of his throat. I closed his eyes. A young, pretty face with long lashes and full lips. I let the lighter go out and stared into the darkness. It wasn’t the first corpse I’d seen, or the first time I’d been in a gunfight with fatal consequences either – but this was the first human being I’d killed with my own hands.

I felt his chest. Like us, he was indeed wearing a bulletproof vest. So the only place to shoot without killing would have been his legs. If he’d realised in time that he couldn’t wound his opponent’s chest, would he have spared my head? And do injured legs stop a man shooting in a life-and-death situation?

A strip of faint yellow light fell into the room. When I turned my head Romario was standing beside me. The light came from a street lamp outside the kitchen window. Romario was hugging himself with his unbandaged arm as if he were freezing. Lips pressed tight, he looked at the body.

I cleared my throat. ‘Er…’ And added, for something to say, ‘It all happened so fast.’

He kept looking down. ‘If that Army of Reason thing really exists, whatever’s behind it, then this,’ he said, jerking his chin in the direction of the body, ‘this means I’m finished in Frankfurt.’

‘Mm,’ I said noncommittally, getting up and lighting a cigarette. We stood in the dim light like that for a while, listening to the noises in the street. Cars drove past, further away a tram rattled along.

I asked, ‘Got any large plastic bin liners?’

‘In the kitchen.’

I trod out my cigarette. ‘Okay. While Slibulsky and I get rid of the bodies you clean this place up, put a notice on the door saying Gone On Holiday, and go home. And tomorrow get out on the first train or flight.’

‘Get out? Where to?’

‘How should I know? Mallorca? Call me and give me a number where I can reach you. In two or three weeks’ time I ought to have found out who’s running this racket and whether they’re after you.’

‘Tell me one reason why they wouldn’t be after me.’

‘Well, they’re certainly extorting money from other people too, so they ought to be suspecting all their victims for a time.’ Oh yes, a long time; about one or two days, I should think. By then at the latest they’d have tracked Romario down, and they’d beat everything they wanted to know out of him – Slibulsky’s name and mine included.

I saw Romario’s outline as he turned away, while his unbandaged arm gestured dismissively in my direction. I guessed what he was thinking: a pity he hadn’t asked someone else for help, someone who worked for money and got a bonus if he succeeded, and for that reason alone would have fixed things to the satisfaction of all, no dead bodies, no need for Romario to close down his business. The problem with friends doing you a favour, is that if they fail then the fact that they came on the cheap just proves how incapable they were anyway.

Apart from that, if Romario was thinking what I thought he was thinking, he wasn’t far wrong. Yes, sure, I’d gone out and got bulletproof vests, I’d persuaded Slibulsky to join us, I’d discussed the showdown in advance with both of them. But really I’d been annoyed all along for feeling that unwritten laws obliged me to help Romario, and for agreeing to meet him at all four days ago instead of making some excuse, say flu. In other words, at this moment, with one body to my left, another to my right and my feet in a pool of blood, I realised that I didn’t like Romario. I didn’t like him at all. He let other people suffocate in the dry air of his central heating because he couldn’t cope with having been born at some time in some place in another part of the world, he was a terrible cook, he thought he was helping me out by inviting me to eat the leftovers now and then – which was true, and that made it all the worse. But it was about ten minutes too late to do anything about this realisation of mine. I was involved now. Even if Romario ran for it, never to be seen again, there were plenty of people in town who’d wonder about his sudden disappearance, and sooner or later it would get around that I’d been seen with him rather often these last few days. Maybe these Mafia characters couldn’t talk, but they could hear and they could probably do their sums too, and if they put two and two together they weren’t likely to think I’d come here for a game of dice. And Mafia outfits aren’t exactly famous for letting you kill their men with impunity.

All things considered, then, our operation had been a total fiasco. In addition, now I had a guilty conscience. Not only did I not like Romario, I really had done him out of his job, his home and his city in one fell swoop. And that when he’d lost his thumb only five days before.

‘Er, Romario…’

‘What?’ a voice barked behind me. Next moment neon tubes flared on, and cold light from the kitchen fell into the dining-room. Sticky patches of red were spreading over the floor and walls around the corpses, which had now stopped bleeding. The red patches were scattered about like exploded paint-bombs. Slibulsky was sitting on a table, cradling his shotgun in his arm like a baby, dangling his legs and staring ahead of him, nauseated.

I turned to the kitchen door. ‘How could I have known they’d shoot straight away?’

Romario’s head briefly appeared in the doorway. ‘It’s your job to know these things! Whether you can do your job is another question!’

Oh, for God’s sake! A couple of smart remarks, that was all we needed! Apart from the fact that it wouldn’t have been entirely inappropriate for him to ask if Slibulsky and I were all right. After all, it was a miracle we’d got out of this intact. Not to mention any feelings we might have about the dead men and how upset we were. I mean, they weren’t just a burst water pipe, and not simply because they did much more damage.

I reached behind the bar, picked up a bottle of schnapps and took a large gulp. Then I bent over the corpses and searched their suits. A silver lighter, a small bottle of mouthwash, two phone cards, half a packet of Dunhills, a nail file, five hundred and seventy marks plus a few coins, three condoms, car keys and two pairs of sunglasses. No ID or driving licences, nothing to give me a clue. I pocketed it all and was about to see what make their clothes were when I found a mobile phone on one of the corpses, tucked into his belt. It was as small and almost as flat as half a postcard. You flipped it open, three fine grooves above and below indicated the receiving and speaking areas, and you keyed in the numbers on a glowing blue touch-pad. I found out how to switch to receive if the mobile rang and put it in my breast pocket.

Romario brought in a stack of folded grey bin liners and a roll of sticky tape. Slibulsky and I packed the corpses into them. Both of us in silence, both trying not to feel anything much. The central heating was still full on, and our hands, damp with sweat, kept slipping off the plastic sacks and the dead men’s limbs.

When we’d finished I went out and looked around for the BMW that went with the car keys. It was black and new and had a Frankfurt registration. I got into it, felt under the seats, opened the glove compartment, looked behind the sun visors, but apart from empty energy-drink bottles, some blackcurrant-flavour sweets, tissues and a big box of powder the car was empty. I noted the registration number, opened the boot and went back into the Saudade.

By now Romario and Slibulsky were scrubbing the floor and walls. Romario glanced up at me, and judging by the look in his eyes he wouldn’t have minded if the blood he was scrubbing away had been mine.

I went into the kitchen and looked for something to help us carry the bodies to the car as unobtrusively as possible. I found a huge double-handled aluminium pan. It was over a metre in diameter and about the same depth. You could cook a whole pig in it, or several hundredweight of vegetables, or anything else that would feed a medium-sized village for a day.

‘What are you doing with that?’ asked Romario as I dragged this monster into the dining-room.

‘It’s never a good idea to load sacks two metres long into a car boot at one in the morning. A pan full of potatoes, on the other hand…’

‘Are you crazy? I’ll never find another pan like that!’

‘You’ll get it back.’

‘You don’t think I can ever make soup in it again after this, do you?’

‘You think the customers will be able to taste them?’

His eyes widened, and for a moment it looked as if he was going to throw his floorcloths in my face.

‘Yes, I do! I’ll be able to taste them! Every time I use the pan I’ll be thinking…’

‘Hey, hang on!’ Slibulsky looked up from his bucket and broke his silence for the first time since the gunfight. ‘What’s all this about your pan?’

Romario turned to him, and his expression softened. I’d been noticing for some time that he was trying to make Slibulsky his ally against me.

‘Yes, exactly! What is all this? It’s my special soup pan for festive occasions!’ he exclaimed, obviously in the belief that for a civilised man like Slibulsky that would close the subject.

‘Oh yes? And what festive occasion do you want to keep it clean for? Your funeral?’ asked Slibulsky.

‘Or your arrest?’ I suggested, leaving the pan beside the grey plastic sausage shapes. Taking no more notice of Romario, we squeezed up the first of the bodies – they were still warm – and rammed it into the aluminium pan, treading it down.

‘Did you notice their faces? They were powdered white,’ said Slibulsky.

I nodded. ‘As if they’d been rehearsing how to be dead.’

After we had looked to make sure the street was empty, we dragged the pan, which now weighed about eighty kilos, to the BMW. We heaved it up and tipped it over the open boot, but nothing happened. The man was stuck. We held the pan in the air with one hand and one shoulder each, tugging at the plastic with our other hands. The bin liner tore, and something slimy trickled over my hand.

‘I’m going to throw up any moment,’ gasped Slibulsky.

I heard a crack. Slibulsky had broken something in the corpse, and it finally gave way. It landed in the boot with a dull thud. We looked at each other’s red, sweating faces and gasped for air. I wiped my hand on my trousers.

When our breathing had calmed down a little I said, ‘Sorry. I really thought we’d only have to put on a tough guy act.’

Slibulsky flicked a damp bit of something off his T-shirt. ‘I only hope Tango Man doesn’t try pinning it all on us.’

‘Pinning it on…?’

‘Well, in theory he could go to the police and say gangsters started shooting his place up. He knows you slightly as a guest, he could say, but he had no idea of your Mafia connections.’

‘Slibulsky, I’m a private detective!’

He stopped, looked incredulous, then uttered a sound between a laugh and a cough. ‘Have your neighbours said a friendly hi to you very often recently? You have a Turkish name, Turkish parents, and since starting this job you’ve infuriated every second cop in town. You don’t think a silly little nameplate on your door will stop them for a second if they have a chance of arresting you as an Anatolian terrorist baron, do you?’

‘It’s not just a plate on the door. I’ve got a licence too.’

This was weak, admittedly, and Slibulsky didn’t even take the trouble to answer it. In fact he was pointing out a possibility that hadn’t for a moment crossed my mind before.

On the way back I said, ‘He’s Brazilian. The tango comes from Argentina.’

‘So what? You knew who I meant, right?’

He was correct there too.

Tango Man was sitting on a chair, feet up on the table, and seemed to have put back several glasses of liquor to calm his nerves while we were outside. ‘Tango Man’ fitted him perfectly: a long, tough-looking face with small, quick-moving eyes, a sharp nose and a cleft in his chin; mid-length hair, black and shining like lacquer, brushed well back and moving when he moved as if it grew from a single root; a body that was big and broad anyway, but looked even bigger and broader in a T-shirt and trousers that might once have fitted him in a school yard in Rio; and his obvious conviction that no one’s ever too tall to wear shoes with five-centimetre heels.

Those eyes, not so quick-moving now, stared at us. We could see how he had to strain his lips to bring out any sound at all. Had he perhaps been putting back not glasses but whole bottles of liquor to calm his nerves? What and how much did you have to drink in just under twenty minutes to reach a state where you couldn’t articulate? There was an empty glass beside him. I looked behind the bar, where I found an empty bottle. He hadn’t eaten anything that evening, what with all the agitation, and normally he stuck to fruit juice.

‘Hey, Romario, this is all a bit much for you, right?’ I went over and put my hand on his shoulder. He looked up at me and gave me a long glance which, I suspected, was meant to express pain, but was only glazed and blurred. Then he silently raised his bandaged arm, looked at it and nodded at it, as if to say: what the pair of us go through together! He looked up at me again, reproachfully this time, until his face suddenly twitched and tears ran down his cheeks. As he wept a kind of whinny escaped him. I kneaded his shoulder, said something like, ‘It’ll all work out,’ and looked around for Slibulsky to come to my aid. But he only shrugged and set about fitting the second corpse into the pan. The whinny finally became sobs, the sobs turned to gulps, the tears abated, I gave Romario a handkerchief and he blew his nose.

‘I… the restaurant’s like a girlfriend to me, see… and the way you’d give a girl jewellery and clothes, I bought it wood and tiles and tablecloths. To make it look pretty, see?’

‘Yes, sure,’ I said, wondering what kinds of presents, judging by the chipboard, fake marble tiles and check polyester tablecloths in this place, he gave his girlfriends.

‘I promise you’ll soon be able to come back here.’ As I said that, the pushing and shoving behind me stopped for a moment, and I sensed Slibulsky’s eyes on my back. Of course, it was more realistic to expect that the Saudade would be blown up some time in the next few weeks, and Romario would have to start all over again with kebabs and canned beer somewhere far away.

‘Sorry about just now,’ said Romario. ‘You’re right, how could you have known they’d start shooting straight away? But I was in shock…’ He looked at me out of eyes that were still moist, and I nodded understandingly. It was just after one, according to my watch. ‘So if you really could fix it, Kemal, I’d be eternally grateful!’ He tried a smile. ‘And you’d have free meals for life!’

Now it was my turn to try a smile. ‘Well, great, Romario. Thanks a lot. But,’ I said, this time glancing at my watch as ostentatiously as possible, ‘we ought to get a move on. By tomorrow this place must be as clean as if nothing had happened.’ I pointed to the bullet-holes in the wooden panelling. ‘You’ll have to fill those in with something and paint them over. Better make yourself a coffee and then see how far you can get with one arm.’