PREFACE.

CHAPTER I.

CHAPTER II.

CHAPTER III.

CHAPTER IV.

CHAPTER V.

CHAPTER VI.

CHAPTER VII.

CHAPTER I.

1813-1831.WAGNER’S

EARLY YOUTH.His

Birth—The Father’s Death—His Mother Remarries—Removal to

Dresden—Theatre and Music—At School—Translation of

Homer—Through Poetry to Music—Returning to Leipzig—Beethoven’s

Symphonies—Resolution to be a Musician—Conceals this

Resolution—Composes Music and Poetry—His Family Distrusts his

Talent—“Romantic” Influences—Studies of Thoroughbass—Overture

in B major—Theodor Weinlig—Full Understanding of

Mozart—Beethoven’s Influence—The Genius of German

Art—Preparatory Studies ended.

“I

resolved to be a musician.”—Wagner.Richard

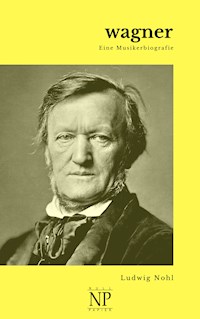

Wilhelm Wagner was born in Leipzig, May 22, 1813. His father at that

time was superintendent of police—a post which, owing to the

constant movement of troops during the French war, was one of special

importance. He soon fell a victim to an epidemic which broke out

among the troops passing through. The mother, a woman of a very

refined and spiritual nature, then married the highly gifted actor,

Ludwig Geyer, who had been an intimate friend of the family, and

removed with him to Dresden, where he held a position at the court

theatre and was highly esteemed. There Wagner spent his childhood and

early youth. Besides the great patriotic uprising of the German

people, artistic impressions were the first to stir his soul. His

father had taken an active interest in the amateur theatricals of the

Leipzig of his day, and now the family virtually identified

themselves with the practical side of the art. His brother Albert and

sister Rosalie subsequently joined the theatre, and two other sisters

diligently devoted themselves to the piano. Richard himself satisfied

his childish tendency by playing comedy in his own room and his

piano-playing was confined to the repetition of melodies which he had

heard. His step-father, during the sickness which also overtook him,

heard Richard play two melodies, the “Ueb’ immer Treu und

Redlichkeit” and the “Jungfernkranz” from “Der Freischuetz,”

which was just becoming known at that time. The boy heard him say to

his mother in an undertone: “Can it be that he has a talent for

music?” He had destined him to be an artist, being himself as good

a portrait painter as he was actor. He died, however, before the boy

had reached his seventh year, bequeathing to him only the information

imparted to his mother, that he “would have made something out of

him.” Wagner in the first sketch of his life, (1842) relates that

for a long time he dwelt upon this utterance of his step-father; and

that it impelled him to aspire to greatness.His

inclinations however did not at first turn to music. He was rather

disposed to study and was sent to the celebrated Kreuzschule. Music

was only cultivated indifferently. A private teacher was engaged to

give him piano lessons, but, as in drawing, he was averse to the

technicalities of the art, and preferred to play by ear, and in this

way mastered the overture to “Der Freischuetz.” His teacher upon

hearing this expressed the opinion that nothing would become of him.

It is true, he could not in this way acquire fingering and scales,

but he gained a peculiar intonation arising from his own deep

feeling, that has been rarely possessed by any other artist. He was

very partial to the overture to “The Magic Flute,” but “Don

Juan” made no impression on him.All

this, however, was only of secondary importance. The study of Greek,

Latin, mythology, and ancient history so completely captivated the

active mind of the boy, that his teacher advised him seriously to

devote himself to philological studies. As he had played music by

imitation so he now tried to imitate poetry. A poem, dedicated to a

dead schoolmate, even won a prize, although considerable fustian had

to be eliminated. His richness of imagination and feeling displayed

itself in early youth. In his eleventh year he would be a poet! A

Saxon poet, Apel, imitated the Greek tragedies, why should he not do

the same? He had already translated the first twelve books of Homer’s

“Odyssey,” and had made a metrical version of Romeo’s

monologue, after having, simply to understand Shakspeare, thoroughly

acquired a knowledge of English. Thus at an early age he mastered the

language which “thinks and meditates for us,” and Shakspeare

became his favorite model. A grand tragedy based on the themes of

Hamlet and King Lear was immediately undertaken, and although in its

progress he killed off forty-two of the

dramatis personae

and was compelled in the denouement, for want of characters to let

their ghosts reappear, we can not but regard it as a proof of the

superabundance of his inborn power.One

advantage was secured by this absurd attempt at poetry: it led him to

music, and in its intense earnestness he first learned to appreciate

the seriousness of art, which until then had appeared to him of such

small importance in contrast with his other studies, that he regarded

“Don Juan” for instance as silly, because of its Italian text and

“painted acting,” as disgusting. At this time he had grown

familiar with “Der Freischuetz,” and whenever he saw Weber pass

his house, he looked up to him with reverential awe. The patriotic

songs sung in those early days of resurrected Germany appealed to his

sensitive nature. They fascinated him and filled his earnest soul

with enthusiasm. “Grander than emperor or king, is it to stand

there and rule!” he said to himself, as he saw Weber enchant and

sway the souls of his auditors with his “Freischuetz” melodies.

He now returned with the family to Leipzig. Did he, while at work on

his grand tragedy, occupying him fully two years, neglect his

studies? In the Nicolai school, where he now attended, he was put

back one class, and this so disheartened him, that he lost all

interest in his studies. Besides, now for the first time, the actual

spirit of music illumined his intellectual horizon. In the Gewandhaus

concerts he heard Beethoven’s symphonies. “Their impression on me

was very powerful,” he says, speaking of his deep agitation, though

only in his fifteenth year, and it was still further intensified when

he was informed that the great master had died the year previous, in

pitiful seclusion from all the world. “I knew not what I really was

intended for,” he puts in the mouth of a young musician in his

story, “A Pilgrimage to Beethoven,” written many years after. “I

only remember, that I heard a symphony of Beethoven one evening.

After that I fell sick with a fever, and when I recovered, I was a

musician.” He grew lazy and negligent in school, having only his

tragedy at heart, but the music of Beethoven induced him to devote

himself passionately to the art. Indeed while listening to the Egmont

music, it so affected him that he would not for all the world,

“launch” his tragedy without such music. He had perfect

confidence that he could compose it, but nevertheless thought it

advisable to acquaint himself with some of the rules of the art. To

accomplish this at once, he borrowed for a week, an easy system of

thoroughbass. The study did not seem to bear fruit as quickly as he

had expected, but its difficulties allured his energetic and active

mind. “I resolved to be a musician,” he said. Two strong forces

of modern society, general education and music, thus in early youth

made an impression upon his nature. Music conquered, but in a form

which includes the other, in the presentation of the poetic idea as

it first found its full expression in Beethoven’s symphonies. Let

us now see how this somewhat arbitrary and selfwilled temperament

urged the stormy young soul on to the real path of his development.The

family discovered his “grand tragedy.” They were much grieved,

for it disclosed the neglect of his school studies. Under the

circumstances he concealed his consciousness of his inner call to

music, secretly continuing, however, his efforts at composition. It

is noticeable that the impulse to adapt poetry never forsook him, but

it was made subordinate to the musical faculty. In fact the former

was brought into requisition only to gratify the latter, so

completely did musical composition control him. Beethoven’s

Pastoral symphony prompted him at one time to write a shepherd play,

which owed its dramatic construction on the other hand to Goethe’s

vaudeville, “A Lover’s Humor,” to which he wrote the music and

the verses at the same time, so that the action and movement of the

play grew out of the making of the verses and the music. He was

likewise prompted to compose in the prevailing forms of music, and

produced a sonata, a string quartet, and an aria.These

works may not have had faults as far as form is concerned, but very

likely they were without any intrinsic value. His mind was still

engrossed with other things than the real poesy of music.

Notwithstanding this, under cover of such performances as these, he

believed he could announce himself to the family as a musician. They

regarded such efforts at composition however as a mere transitory

passion, which would disappear like others especially so as he was

not proficient on even one instrument, and could not therefore assume

to do the work of a practical musician with any degree of assurance.

At this time a strange and confused impression was made upon the

young mind, which had already absorbed so much of importance. The so

called “romantic writers” who then reigned supreme, particularly

the mystic Hoffmann, who was both poet and musician, and who wrote

the most beautiful poetic arrangements of the works of Gluck, Mozart,

and Beethoven, along with the absurdest notions of music, tended to

completely disturb his poetic ideas and mode of expression in music.

This youth of scarce sixteen was in danger of losing his wits. “I

had visions both waking and sleeping, in which the key note, third

and quint appeared bodily and demonstrated their importance to me,

but whatever I wrote on the subject was full of nonsense,” he says

himself.It

was high time to overcome and settle these disturbing elements. His

imperfect understanding of the science of music, which had given rise

to these fancies and apparitions, now gave place to its real nature,

its fixed rules and laws. The skilled musician, Mueller, who

subsequently became organist at Altenburg, taught him to evolve from

those strange forms of an overwrought imagination the simple musical

intervals and accords, thus giving his ideas a secure foundation even

in these musical inspirations and fantasies. Corresponding success

however, had not yet been attained in the practical groundwork of the

art. The impetuous young fellow and enthusiast continued inattentive

and careless in this study. His intellectual nature was too restless

and aggressive to be brought back easily to the study of dry

technical rules, and yet its progress was not far-reaching enough,

for even in art their acquisition is essential.One

of the grand overtures for orchestra which he chose to write at that

time instead of giving himself to the study of music as an

independent language, he called himself the “culmination of his

absurdities.” And yet in this composition, in B major, there was

something, which, when it was performed at the Leipzig Gewandhaus,

commanded the attention of so thorough a musician as Heinrich Dorn,

then a friend of Wagner, and who became later Oberhofkapellmeister at

Berlin. This was the poetic idea which Wagner by the aid of his

mental culture was enabled to produce in music, and which gives to a

composition its inner and organic completeness. Dorn could thus

sincerely console the young author with the hope of future success

for his composition, which, instead of a favorable reception, met

only with indignation and derision.The

revolution which broke out in France in July, 1830, greatly excited

him as it did others and he even contemplated writing a political

overture. The fantastic ideas prevalent at that time among the

students at the university, which in the meantime he had entered to

complete his general education, and fit himself thoroughly for the

vocation of a musician, tended still further to divert his mind from

the serious task before him. At this juncture, both for his own

welfare and that of art, a kind Providence sent him a man, who,

sternly yet kindly, as the storm subsided, directed the awakening

impulse for order and system in his musical studies. This was

Theodore Weinlig, who had been cantor at the Thomasschule in Leipzig,

since 1823 and was therefore, so to speak, bred in the spirit and

genius of the great Sebastian Bach. He possessed that attribute of a

good teacher which leads the scholar imperceptibly into the very

heart of his study. In less than a year the young scholar had

mastered the most difficult problems of counterpoint, and was

dismissed by his teacher as perfectly competent in his art. How

highly Wagner esteemed him is shown by the fact that his “Liebesmahl

der Apostel,” his only work in the nature of an oratorio, is

dedicated to “Frau Charlotte Weinlig, the widow of my

never-to-be-forgotten teacher.” During this time he also composed a

sonata and a polonaise, both of which were free from bombast and

simple and natural in their musical form. More important than all,

Wagner now began to understand Mozart and learned to admire him. He

was at last on the path which subsequently was to lead him, even

nearer than Beethoven came, to that mighty cantor of Leipzig, who by

his art has disclosed for all time the depths of our inner life and

sanctified them.For

the present it was Beethoven, whose art unfolded itself before him,

and now that his own knowledge was firmly grounded, aided him to

become a composer. “I doubt whether there has ever been a young

musician more familiar with Beethoven’s works than was Wagner, then

eighteen years of age,” says Dorn of this period. Wagner himself

says in his “Deutscher Musiker in Paris:” “I knew no greater

pleasure than that of throwing myself so completely into the depths

of this genius that I imagined I had become a part of him.” He

copied the master’s overtures and the Ninth symphony, the latter

causing him to sob violently, but at the same time rousing his

highest enthusiasm. He now also fully comprehended Mozart, especially

his Jupiter symphony. “In the genius of our fatherland, pure in

feeling and chaste in inspiration, he saw the sacred heritage

wherewith the German, under any skies and whatever language he might

speak, would be certain to preserve the innate grandeur of his race,”

is his opinion of Mozart expressed in Paris a few years afterward. “I

strove for clearness and power,” he says of this period of his

youth, and an overture and a symphony soon demonstrated that he had

really grasped the models. After twenty years of personal activity in

this high school of art, he succeeded in thoroughly understanding the

great Sebastian Bach, and reared on this solid foundation-stone of

music the majestic edifice of German art, which embraces all the

capabilities and ideals of the soul, and created at last a national

drama, complete in every sense.The

school period was passed. He now entered active life with firm and

secure step, armed only with his knowledge and his power of will. In

his struggles and disappointments the former was to be put to the

test and the latter to be strengthened. We shall meet with him again,

when by the exercise of these two powers he has gained his first

permanent victories.