Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

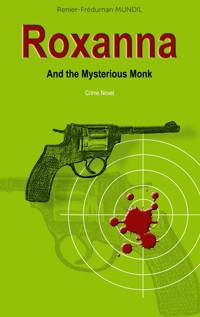

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

If someone wants to experience a lot, a journey with the moon is a good idea, if someone wants to experience even more, a journey with death. But how does someone travel with death? Even if we sometimes have the feeling that our lives are boring and dreary, no life is monotonous. Like a fugue, it is accompanied by two, three, four or even more melodies. What does death look like? He is said to have appeared as Father Death, Reaper, Bone Man, Grim Reaper. But let us not dwell on that. It is about a journey, and such a journey has to begin at some point, even if it is a journey with death.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 187

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To the plants of the night

To a human being

To us

Contents

“When someone goes on a journey, he has a story to tell!”

Thus begins a 14-verse poem by Matthias Claudius, the poet who incidentally wrote by far the best-known German poem with the text:

„Der Mond ist aufgegangen“ [The moon has risen]. His travel poem takes us to the North Pole, Greenland, the Eskimos, America and Mexico and mentions the sea as well as Kiel, Aysen, China, Bengal, Japan, Otaheit (Tahiti) and Africa. All areas that the night-traveling moon has seen an infinite number of times after rising. Only death has traveled even further. There is life everywhere on earth and where there is life, death will sooner or later be present.

If someone wants to experience a lot, a journey with the moon is a good idea, if someone wants to experience even more, a journey with death. But how does someone travel with death? Even if we sometimes have the feeling that our lives are boring and dreary, no life is monotonous. Like a fugue, it is accompanied by two, three, four or even more melodies.

As an aside, Johann Sebastian Bach was the master of the fugue.

The ultimate in literature and music would be the poem “Der Mond ist aufgegangen” set to music as a fugue by Johann Sebastian Bach.

The fact that this did not happen is probably (also) due to death. Bach died in 1750, when Matthias Claudius was only ten years old.

This book only describes one of the many journeys that death undertook. With whom and where? Yes, with whom and where does death travel? Two legitimate questions.

However, questions cannot be answered simply because they are legitimate. Other questions arise. What does death look like? He is said to have appeared as Father Death, Reaper, Bone Man, Grim Reaper.

“Come in, unless it is the reaper!” people used to say. Who likes to invite the reaper, death? Over time, this unwelcome greeting became “Come in, unless it is a tailor!”

In this way, death would travel disguised as a tailor. Not so far-fetched, who better to disguise oneself than tailors, who by profession are able to weave the most incredible disguise costumes.

But let’s not dwell on that. It’s about a journey, and such a journey has to begin at some point, even if it is a journey with death.

Prelude Singing

What has been does not return, because everything has long been there.

The past has its roots in the future.

The present does not exist because we cannot hold on to the moment to measure it.

Death is the chain that connects everything.

Like drops of air, we slip through the openings of this chain, not knowing if we will ever wake up from the dream of life.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Swan song

Biography

1.

Well, old mother, you are new with us.

The plump woman sat down on the arm of the chair and mechanically stroked her wrinkled face. Mother was the new entry, almost every day they had entries here, entries, what a word. Most couldn't even walk, they were walked, became a registered entry at the bleak end of their lives, inventoried and managed, an object that meant work and livelihood for others.

The plump woman rose. The bulky figure spilled out of the sterile white coat, whose immaculate white stood out strangely alien against the grey of the entries.

Now sit here, old mother, and later, later we'll get you!

The old woman stared ahead. In the abysses of her tired eyes flickered motionless horror, too sparse, however, to set her legs in motion as a source of energy, to drive her to the exit. Like a ghost train, old figures shuffled past her, heads bent far down, feet mechanically shuffling across the floor, a viscous mass clinging stickily to life and moving slowly towards the dining room.

We'll come back for you later!

Two boots smashed against the finely chiseled wooden door, which willingly jumped out of its frame and crashed to the floor. At last a new feeling for a door, not always the involuntary opening and closing when others stepped through it.

The heels of the boots dug into the lying door and the old wood felt strangely significant under the new steps of time. Inside the house the boots parted, soon driving people out of every room, whipping them outside with the force of their words. Boot kicks dug into bodies, the clinging splinters of wood slid from the soft rubber into the comforting warmth of fleeing heated bodies.

Little Marla stared out of the slit of the linen chest at the fleeing people being picked up. The tiny eyes began to cry, salty water rolled over the delicate skin and disappeared in the distorted mouth. Marla tried to scream, but her sister Manu pressed her hand over her mouth as if to crush her voice. Suddenly, silence fell. The fleeing bodies paused, the black boots stopped and turned around.

If someone was hiding?

So what, we'll get them later.

An order is an order, so do it now!

I’m not going to search that filthy stable. But I have another idea.

Like what?

The hands of the other boots moved to the level of the waistband and pulled out a black object. Shortly after, a volley of gunshots riddled the linen chest, bullets piercing the soft down of the quilts, white pure feathers floating around the room like snow crystals.

No, not the chest!

A hysterical female voice rang through the room. A boot kicked her violently; without a sigh, the scream died away.

With the infinity of a moment, the bullet bored through the old oak wood of the chest, floated through the linen, started a little when in the darkness the innocent little face suddenly appeared, nevertheless continued its enforced way. The hot lead melted into the whiteness of the skin, covering itself with a dripping red sheath before smashing against the delicate bones of the skull. The black boots grinned. Manu felt her sister's blood run over her skin, warm, sluggish, in rhythmic petering out strokes. She pressed her sister to her, wanting to enclose her like a shield so that no bit of life could leave the little body. Her tears mingled with the red stream and settled over the little shelllike pleasant dew. Then it was over.

Well, old mother, now it's time for dinner. I'm supposed to get you.

2.

The monks were walking in a long procession through the bare mountainous area. Their voices blended with the sounds of the instruments they carried, bounced against the rocks, and from there rose distorted into the sky. It took a while before the first bird appeared in the sky. Ponderously it let itself be carried by the air filled with sounds and circled above the procession like an airplane in a waiting loop. It opened its beak, emitted muffled sounds that joined the voices of the monks and the sounds of the instruments to form a fleeting symphony.

Soon others of its kind appeared, twenty, thirty massive bodies circled in the air. The monks moved on, followed by the attracted birds.

A small plateau appeared behind the hilltop. Laid out on stones placed one against the other, a motionless human figure could be made out. Anxious furrows had been dug into the face by the capricious weather in the course of time. Motionless eyes stared out from the dead body as if fixing the dark spots above.

A little way off, the procession ended, continuing the chanting. Ponderously, the large birds landed a short distance away. Clumsily they hopped across the plateau, surrounding the lifeless, laid out body. Almost questioningly, they looked at the monks for a moment, then hacked their massive beaks into the dead cold flesh.

Motionless and silent, the monks followed the spectacle. From time to time sounds of cracking bones broke the silence. As if in a trance, the monks watched the circle of birds, waiting for them to free the soul of the deceased from the prison of the cold body through their work.

What remained was a gray skeleton of bones. The lattice bars of the ribs, prison of the life odem, broken, the hollows of the skull hollowed out. In some places the birds had so polished the bone with their beaks that a pure white emerged and stood out strangely against the gray rocky landscape.

Suddenly, a black eagle soared through the air. Weightlessly it glided to the ground, the stuffed vultures trotted ponderously to the side. The eagle grabbed an exposed bone and soared into the air. From high above, it let the bone crash to the ground, where it shattered against the sharp rock. The bird glided after it, landed in the middle of the splintered bone and began to devour the sharp remains.

Come old mother, I'm supposed to fetch you.

3.

On .. .. .. , the date is irrelevant, it has been repeated a million times, Marla, Manu's little sister, was born. It was autumn, the wind began to drive the velvet green from the leaves, from the invisible air wondrous colors crept into the trees, transforming them into bright flowers that blossomed one last time. People trotted through the avenues, isolated vehicles scurried by, human feet carelessly crushed wizened apples that the tired trees had shed, unaware that only a few years later they would be ploughing through the ground by the meter with their bare fingers to find an old round edible fruit. Up in the air, airplanes circled, quietly, smoothly, only the somewhat rattling sound of engines foreshadowing the purpose for which they were built, that they were about to practice smashing death from the sky to the earth.

Little Marla lay secure against her mother's warm naked breast, sucking with nostrils flaring at the dark nipple, sucking greedily at the new life. Her big sister, already steeped in this life for ten years, stood wordlessly by. It might be another ten years, then she would lie like this, eyes closed, a small naked body against her bosom, sucking up a part of her life.

She remembered the big fish swimming upstream through the cold water, only to leave their spawn, exhausted and tired, to die afterwards. It's a good thing that Mummy wasn't a fish, otherwise she would die soon and she had to drag the little creature around the world.

Well, Manu, do you like her?

The girl nodded wordlessly. Her fascination had left her speechless, she gazed silently at the new life.

What is it, Manu, are you sad?

Her mother pulled her close to her, pulled her face to her other breast. Manu felt the warm, soft pulsing of bare skin. She looked directly into the eyes of the newborn life, but the little being's gaze passed her by unblinkingly, piercing the dim windows and moving into the new world. The old wooden door burst open, creaking, heavy, and Manu's brother entered.

Manu come, Daddy says I'm to fetch you.

Where to? squeaked Manu.

To the city. Shopping. Maybe we'll go to the funfair, too.

Manu looked indecisive.

Go on Manu, your sister won't run away from you.

Go on Manu, let them come and get you.

When the young woman returned home, she already suspected what had happened. The events of the last few weeks had furrowed her face from the inside, and nothing in her countenance reminded her of the pulsating life that roared through her unused body.

Oh Raisa, what misfortune, Raisa, my good one. Raisa, my little one!

The young woman looked into her mother's face, her plump cheeks held together by a headscarf, streams of tears spilling from her eyes, their drops forming strange pools on her upper body.

My Raisa, oh woe is me!

Raisa saw a group of older men digging a pit next to the house. Winter was coming, any night the frost could come and turn the soil of life into stone. The practical side of life rolled away the time of mourning with a stroke of the pen.

Where is he? Raisa asked in a choked voice.

They put him in the bedroom.

Raisa went to the house, her mother followed.

Rudely, she pushed the old woman aside:

Leave me alone! Leave us alone!

Distraught, the old woman moved away from the path, falling heavily on to an old wooden bench that stood next to the woodshed. Raisa entered the bedroom, for the last time she was alone with her husband in the small room where she had shared her most personal hours with a human being.

The dead body of her husband lay on her side of the bed. It had probably been too difficult to lay him out on his side in the narrow room, because the marital bed on his side was up against the wall. Motionless, Raisa looked at the body. On the center of his forehead, where she tenderly kissed him goodbye every morning, a sticky pool of blood had formed. Shot in the head. Sniper or stray bullet from this damned war. Why hadn't it flown five inches higher? Why hadn't an A-bomb blown the sniper to pieces before?

Till death do you part!

Raisa thought of her marriage. Out of embarrassment to herself, she pushed aside thoughts of their wedding night in that bed. She had remembered it sometimes, now was not the appropriate moment to follow that sudden thought, the time for remembering it had expired.

She left the room, went to the basement and returned with a saw, hammer and other tools. Like a machine, her arms worked with the old hacksaw.

Startled and confused, her mother rushed into the room at the regular buzzing of the saw blade.

Raisa, no dear, what's wrong with you?

What a misfortune. And now this. Had her daughter gone mad? It would not be unusual in this situation, one often heard about it. The events drove people out of their minds, some went mad, others went astray or were willingly led astray.

Raisa, my child, what are you doing?

The old woman only saw the pool of blood that was slowly forming at the end of the bed, where the saw mechanically slid back and forth.

The pool came from her daughter. She had hurt herself, involuntarily sacrificing some of her blood for the last service of love to her husband.

Let it be, mother, said Raisa, I have never known more exactly what to do than at this moment. I will never again share my bed with a human being. This half of the bed is no longer necessary, never again, but it will serve another purpose. At this, she laughed strangely.

For several hours the sounds of the saw, the pounding of the hammer, and the groans of the young woman because of the unaccustomed work carried outside.

None of the men who had dug the pit in the garden, nor the old woman, dared to enter the house. At last the door opened, Raisa appeared, worn, pale and sweaty, standing under the low doorframe, searching the grey homestead with lifeless eyes and dropping silently on to the wooden bench.

Come and get him!

4.

At night, the low rumble of artillery could be heard, persistently approaching the small village. Raisa slept fitfully, her husband's death, the approaching war denied her the soothing, carefree peace of deep sleep.

She turned to her side to snuggle against her husband as she had loved to do for years. Instead of the warmth of another person, she fell into a black hole, finding herself on the cold floor, where the other half of the bed had been just a day ago. Raisa awoke. The artillery fire was now menacingly loud. Under cover of night, the enemy must have moved out of the forest toward the village.

She jumped up and ran into the next room. Seconds later, a grenade hit the garden, flying sparks illuminating the surroundings. Raisa stared out of the window. The grenade had hit the spot where they had buried her husband yesterday.

The graves were opening up. The dead were not allowed to rest, why should they have it better than the living?

Outside, a black figure flitted through the bushes. Raisa narrowed her eyes. She recognized her little daughter, with a bunch of flowers in her hand she was running to her father's grave.

Manu, Manu, her voice echoed through the house, window panes shattered, the small family photo on the dresser crashed to the floor and shattered on the bare boards.

Manu, Manu.......

The child turned round. Like a startled deer, it paused under the old walnut tree, petrified by the menace of the moment.

A second figure appeared in the garden, her son. He grabbed his sister and dragged her towards the house. The girl fell, the flower arrangement burrowing into the dirty earth, the boy dragging her on through the darkness cut by the mother's hysterical screams.

A final detonation, more violent, much more violent than the previous ones. Then a silence fell, such as had never before lain over the small village. Raisa opened the heavy old book, which had passed through generations of the family:

When he came near the city gate, they were carrying out a dead man. He was the only son of his mother, a widow. And many people from the town accompanied her. When the Lord saw the woman, he had compassion on her and said, "Do not weep. Then he went to the bier and touched it. The bearers stopped and he said: I command you, young man: Get up!” Then the dead man got up and Jesus gave him back to his mother.

Raisa opened her eyes. In front of her stood her son, in his arms he held little Manu.

Let's go and get the others, said Raisa, it's time to be on our way.

As her boy's figure disappeared, she looked outside in the light of a torch. The walnut tree lay shattered over her husband's grave. Through the branches, she made out pieces of the coffin that the earth had spewed out under the force of the detonation. She turned out the light. There were sights that even death had not taught her to bear. She did not even possess the strength to cry anymore.

Manu, my little one, will you send for me? My boy, where are you? Aren't you coming to get me?

5.

And now I'll show you your room first. The plump woman, her feminine curves spilling out of her white coat, grabbed the wheelchair and pushed the newcomer through the narrow hallway.

Once this had been a mansion, after the war it served as a granary, and most recently it had been converted for the elderly. Doors opened and haggard figures pushed their grinning faces through the gap to the outside.

At the door stood a being that had been mechanically swaying its upper body back and forth for an hour already, the caregivers were glad that the figure was taking care of itself in this way.

Here is your new home!

The nurse waited a moment for the figure to sway to the right and, in a flash, pushed the wheelchair through the crack that had appeared for a fraction of an instant with the door.

A room with endlessly high ceilings opened up. Old stucco remnants hung on the walls, old paintings shimmered under the many layers of paint and wallpaper, testifying to glorious times past. In the farthest corner stood a bed in which an old emaciated female figure lay. Two nurses had undressed the shrunken body and were just turning it to the other side to soap its back. Opposite was another bed, the figure of an old woman staring with empty eye sockets at the window, where the mild sunlight washed around the elaborate cobwebs, as if she were looking for something familiar far out in the unknown. Incoherently, she stammered words that drifted as fine wisps through the stuffy air of the room.

The third bed was empty, its owner still standing by the door, rocking from one side of the doorframe to the other like a perpetual motion machine.

One of the nurses turned round:

Is she incontinent?

The corpulent colleague shook her head.

At least not that, the other breathed a sigh of relief.

She came to the wheelchair and they both grasped the new old one under the arms, lifted her up and laid her on the bed.

Do you actually have children? the nurse asked. The old woman nodded.

Well then, you will soon have visitors.

The old woman took a small photo out of her bag:

Would you like to see?

But when she looked up, the two nurses had already disappeared. She could only make out the outlines of their white coats dipping into the dark grey of the corridor. With shaky hands, she took the yellowed sheet pasted on the back of the photo, unfolded it and read the greying letters for the umpteenth time: