5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Signum-Verlag

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

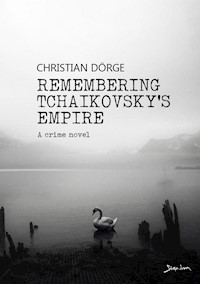

Linnet Restorick and her husband Simon come as summer guests to Swan Lake House—on an island on the English west coast. But the idyllic island and the gloomy house soon turn into a hell of intrigue and murder... With the novel REMEMBERING TCHAIKOVSKY'S EMPIRE, Christian Dörge, author of several crime novels and crime series, presents an equally exciting and nostalgic homage to Agatha Christie’s work.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

CHRISTIAN DÖRGE

Remembering

Tchaikovsky's Empire

A crime novel

Signum-Verlag

Content

Imprint

The book

The author

REMEMBERING TCHAIKOVSKY'S EMPIRE

The main characters of this novel

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Imprint

Copyright © 2023 by Christian Dörge/Signum-Verlag.

Editing: Dr. Birgit Rehberg.

Translated into English by Mina Dörge.

Original title: Erinnerungen an das Reich Tschaikowskys.

Cover: Copyright © by Christian Dörge.

Publisher:

Signum-Verlag

Winthirstraße 11

80639 Munich/Germany

www.signum-literatur.com

The book

Linnet Restorick and her husband Simon come as summer guests to Swan Lake House—on an island on the English west coast. But the idyllic island and the gloomy house soon turn into a hell of intrigue and murder...

With the novel Remembering Tchaikovsky's Empire, Christian Dörge, author of several crime novels and crime series, presents an equally exciting and nostalgic homage to Agatha Christie’s work.

The author

Christian Dörge (* 1969).

Christian Dörge is a German writer, playwright, musician, theatre actor and director.

First publications 1988 and 1989:

Phenomena (novel), Opera (texts).

From 1989 to 1993 director of the theatre group Orphée-Dramatiques; Dörge staged and directed his own works, including Eine Selbstspiegelung des Poeten (1990), Das Testament des Orpheus (1990), Das Gefängnis (1992) and Hamlet-Monologe (2014).

Since 1987: Various publications in anthologies and literary periodicals.

Publication of the collections Automatik (1991), Gift and Lichter von Paris (both 1993).

Since 1992, successful as composer and singer of his projects Syria and Borgia Disco as well as spoken word artist in the context of numerous literary settings; he released of over 60 albums, including Ozymandias Of Egypt (1994), Marrakesh Night Market (1995), Antiphon (1996), A Gift From Culture (1996), Metroland (1999), Slow Night (2003), Sixties Alien Love Story (2010), American Gothic (2011), Flower Mercy Needle Chain (2011), Analog (2010), Apotheosis (2011), Tristana 9212 (2012), On Glass (2014), The Sound Of Snow (2015), American Life (2015), Cyberpunk (2016).

Return to literature in 2013: publication of the plays Hamlet-Monologe and Macbeth-Monologe (both 2015).

In 2021, Christian Dörge publishes several crime novels and begins three novel series: Die unheimlichen Fälle des Edgar Wallace, Ein Fall für Remigius Jungblut and Friesland.

Two more crime series follow in 2022: Noir crime novels about the Frankenberg private detective Lafayette Bismarck and Munich crime novels featuring Jack Kandlbinder, who has to solve the strangest crimes in the Bavarian capital.

Also in 2022, Tristana—Eine Werkausgabe is published, an extensive retrospective of Dörge's more experimental literary works.

In early 2023, he released his new album Kafkaland.

Homepage: www.christiandoerge.de

REMEMBERING TCHAIKOVSKY'S EMPIRE

The main characters of this novel

Simon Restorick: professor of history, psychology, and sociology.

Linnet Restorick: his wife.

Daisy Restorick: their daughter.

Graham Marshall: professor and owner of Swan Lake House.

Arlena Marshall: his wife.

Sam Castle: doctoral student of Professor Marshall.

Dr. Rex Vernon: country doctor and coroner.

Dr. David Lee: vet.

Veronica Christow: nurse.

Alfred Stokes: farmer.

Tobias Stokes: his son.

Detective Lieutenant Patrick Lee: county police officer.

Philip Craven: chief of the local police.

Steve Black: pathologist.

Simenon Marshall: diplomat and Graham Marshall’s eldest brother.

This novel is set on an island on the west coast of England in 1970

Chapter One

Without a doubt, the Restoricks would have been the happiest holidaymakers on the island if nothing else had marred their peace of mind than the road to Graham Marshall’s summer home. Said road, where it did not curve stonily, was deeply rutted, as overgrown as a path in the rainforest and almost as steep as a wall. The old car shook like a worn-out warhorse, backed up, snorted and struggled uphill, belching steam from the front, black smoke from the rear, while Linnet held her breath and Simon clutched the wheel, cursing.

An omen, she thought. If only we hadn’t come. It won’t work. It can’t...

Halfway up the hill, a lane branched off to the right at a weathered, illegible sign, but they continued up and reached a round place, flat as a plate of mixed lettuce. In the middle, bordered by a ring of sand, grew blackberry and honeysuckle, low blueberry bushes, cheeky yellow coneflower and shy white daisies. Between them loomed a dishevelled pine, as stubborn as the sea wind that had deformed it, inhabited by an excited jay. Behind it, nestled against the hill’s farther flank and facing the glittering sea, lay an elongated, low house, its white cedar shingles beginning to take on that silver sheen so coveted in England.

“Good God!” groaned Simon, sweating and panting, as they stopped at the back door. “Marshall said you must take the incline in first gear. In what, for fuck’s sake!”

“In a new car. He could only have meant it that way.” She laughed to neutralise her already chronic irritation.

He went into it endeavouring blithely. “Look here: I will do my utmost to win a car in the raffle, at the next best folk festival. What do you say” He wiped his face on his sleeve and grinned sheepishly.

“How noble of you. Thank you.” She felt her face contort into a wry smile.

The foundations of their marriage had been crumbling ever since that rainy night in Cornwall when Linnet had fallen asleep behind the wheel, and no attempt to save their marriage had ever been as anxiety-ridden as this one. There they sat, looking around, not daring to move, not daring to surrender to the undisturbed togetherness that lay ahead of them for a fortnight under the Marshalls’ roof.

“Why are we sitting here when the house is waiting?” he asked after a while. “Looks great. Really comfortable. Fitting for a house called Swan Lake.”

“I don’t know if I wouldn’t be sitting here if this wreck was a fully air-conditioned Rolls-Royce with flowing cold and warm whiskey.”

“Save your impulses. I’m not in the mood for it. God knows I’m even more tired than you are.”

Yes, she thought. It’s very tiring to chauffeur with one hand, although that’s one of the few things you're still able to do—and which you keep reminding me of. That’s another of your peculiarities, poking at the wound. I do five times more than I used to in order to fill the gaps. Maybe I did too much. Maybe it was wrong...

The dog behind them stirred, got up to look out the window, and Linnet leaned back to open the door for him. “Go on, Frey,” she urged him. “A walk will do you good.” But the dog turned away from the scene, disinterested, dropped down, yawned and went back to sleep. Simon, as if infected, yawned too, and they remained sitting, admiring the green, flowering splendour all around.

“Incredible,” she murmured. “Have you ever seen such a garden? A genius was at work here. The most beautiful garden I ever had was a schoolyard compared to that one. It’s awful to start the holidays with an inferiority complex. If it’s the same inside as it is outside, I’d rather leave right away... Simon, who are these people, the Marshalls?”

“I don’t know his wife. Himself only slightly. But he’s nice. Well-behaved, indeed. Friendly. Long, lean mountaineer type, about fifty-five. Busy all the way out there. I like him, and I’m sorry he’s taking his leave now that I’ve finally managed to get into this university. I only made it after fifteen years of teaching in all sorts of places—I will never take my leave! How can he imagine ever finding anything that equals or even surpasses the university?”

She asked herself the same question. Hort of education it had always been called with Simon. “Did he comment on that?”

“Yes. After twenty-five years he’s longing for a change, for a new life. I can understand that, but something like this! He’s giving up the deanship and the public spotlight for a measly school inspector's job in a place like Blakewell! He’s not in it for the money, though he’ll get a bit more now, he says. He’s swimming in mammon—all those published books, guest lectures and talks. He also has private wealth—he comes from an old London family. But I still think he’s crazy!”

“Why is he letting us have the house?”

“Probably a gesture: I come, he goes. As it happens, I mentioned that we hadn’t booked a holiday yet, and that’s when he said we could stay here on Swan Lake while he sorted out his affairs at the university and moved.”

“Nice gesture—at a hundred and fifty pounds a week.”

For three months he had been talking about a holiday, but he had done nothing, of course, but Simon had always refused her offer to take care of it: there were still things even a cripple could do, he had said.

He was beginning to get bored and nervous. “What about it? Are we going in?”

“I’d prefer the fishing hut we stayed in last year.” She sighed and reached for the door handle like someone determined to take the plunge. “Come on, kid,” she said to the seventy-pound behemoth in the back seat. One moist brown eye blinked listlessly at her. She got out to see what was wrong with the dog. “Listen, Frey, if you don't get out of this wreck right now, you’re going to blow up and explode,” she warned him as she gently placed a hand on his forehead.

“Does he have a fever?” Simon asked anxiously. At least his caring and feeling for the children had not changed.

“Hardly at all. No hot glow in his eyes. Well, come on, old house, get up! Like this! That’s the way. There now.”

Frey acted as if he had never seen dusty earth before, and entered it like burning coals. The jay immediately began to hurl a hail of insults at him. Frey, meanwhile, ignored it majestically like an ageing lion and strode leisurely around the bird’s little kingdom. They watched in alarm, but when the dog chased after a butterfly, Simon unlocked the front door. They entered.

And stood rooted to the spot.

Chapter Two

The long hallway was dark because all the curtains in the rooms leading from here were drawn. It seemed as if the room had sucked in the hot, stuffy air from all directions. The atmosphere was positively saturated with the exhalations of damp flower-pot soil and rot. The cause was quite harmless, as was soon to become apparent. But Linnet flinched and touched the door. Suddenly... the radiant afternoon beyond was very far away.

Simon fumbled for the light switch. “Blimey! Let’s get some air inside first—quickly! Marshall said his caretaker would take care of that.”

They scurried from room to room, pulling curtains apart and tearing open windows.

“It’s absurd, but I feel as if I’m doing something altogether forbidden,” she whispered, wincing when he said, “Goodness, why are you whispering? We’re going to unpack and have something to eat.”

“First, we’ll have a quiet look around. Who knows—we might lose the desire to stay.” She shook herself. “There are just too many plants, and they’ve had far too much water. It smells like open graves after a tropical storm!”

They were in the spacious kitchen, which was lower on the hillside than the rest of the house by about half a metre. With the curtains closed it had seemed like a dark cave, but now light streamed in from three sides. Above the sink there were two small windows, opposite them a glass door with six panes leading to a sun terrace. The picture window in the long wall offered a view of the green hill that sloped down to the sea: a shimmering lavender blue that faded to a soft grey and then merged with the distant horizon.

“No wonder they allowed us to take Frey,” she said, pointing to an empty birdcage above the sink and several plastic bowls. “They must have a zoo!”

There were dozens of frugal begonias on all the windowsills, on wall shelves, table and hanging cupboards.

“Dear God, doesn’t Mrs Marshall have anything else to do but look after them?” She looked unkindly at the piles of wilted flowers this plant had shed. “Begonias are an abomination to me. Come, let’s see if they have a philodendron somewhere.” She walked expectantly over the step into the living room, which immediately adjoined the sun terrace.

A neat single philodendron hung from a console next to the huge picture window that framed a grand view of sky and sea, but there were other plants, mainly begonias. They stood in a long row under the window, on the mantelpiece, on the coffee table and scattered across the packed bookshelves that took up an entire wall. The cachepots, a handsome and imaginative collection, had been created not only by the hands of eagerly experimenting locals, but also on the other side of the world on potter's wheels that had been idle for five hundred years.

The furniture was a pleasant mixture of rattan, iron, antique cherry and maple wood. The coffee table was made from a huge, beautiful piece of driftwood and weighed at least one hundred and forty kilos. A thick textured rug covered the planked hardwood floor. On either side of the fireplace was a wicker lounger, one large, the other small. Everything was pleasantly clean and tidy, and scattered odds and ends that had accumulated over a lifetime gave the room a cosy appearance.

“But not a warm one, not a welcoming one,” she murmured as Simon went to try out the couch. She turned to the books as if they could tell her why it was so. But she only discovered that the Marshalls read everything from archaeology to botany, education, psychology, law, sexology and zoology. And they grouped the books curiously: Lassie stood wedged between The Naked Ape and The Human Zoo by Desmond Morris, three Ian Flemings and two Mickey Spillanes in colourful protective covers stuck boldly between Asimov, Kafka and Lessing.

“Well, now I can answer myself,” she said thoughtfully. “Let’s get on with it before I...” She paused.

“Before you—what? Never mind!” he said irritably. “I want to unpack, eat something and then lie down for a bit. This couch is quite decent. Just not long enough.”

“Too bad,” she said indignantly and went into the hallway. “It still smells awful in here. Did he say where we could sleep?”

“Why should he? We’ll use the bedroom, of course. It must be this one, here on the left.”

“Sure. It has its own bathroom.”

“What’s wrong with it again?” he groaned, but she made no reply, for no doubt he basically didn’t want to know.

Silently, separated by a virtually unbridgeable gulf, they surveyed the bedroom and bathroom, and then Linnet read the titles of the books piled on one bedside table, wondering which of the Marshalls was into law. Simon, meanwhile, was looking at a decoratively framed family tree that hung opposite the bed.

In the bottom left-hand corner, in cobweb-fine old-fashioned handwriting executed with a split quill, was the signature Simenon Nathaniel Marshall, dated 25 December 1912. The earliest year on the family tree was 1674 (Aaron Marshall), the latest 1957 (Edward Marshall).

“This is Graham,” he said, pointing to the plaque. “1916, married to Arlena Carbury. So, he’s young Edward’s great uncle. Hmm... Strange.”

“What’s odd about that?” she asked, a little hysterically. “And there are still nine dripping wet plants in here and three in the bathroom! Three on the water tank too!” She sat down on the bed, sullenly.

“Look at that! It is taken down and added to from time to time. Here the entries are made in a different ink, starting with the descendants of Simenon senior, of which Graham is one. Simenon junior—1900—who made this at the age of twelve, apparently wanted to give it to his parents for Christmas. But his wife and children, as well as their wives and children, have been inscribed in a different ink, blue, along with the years of birth. Only Arlena’s birth year is missing.”

She stood up to look at it.

“No birth year—and no descendants. I thought so.” She stared sadly at the branch of the tree that no longer thrived or bore fruit.

“Why? And what do you think now?” he sneered.

“If only you cared about that, then I’d be delighted to let you know.” Jesus, why did I just say that, she thought to herself. “Come on, let’s finally end this sightseeing.”

In a short narrow corridor that branched off at right angles from the hallway, they discovered two doors facing each other. The room behind one was sparsely furnished and contained no plants. It was clearly the guest room, as could be seen from the pull-out bed.

Behind the other was a study, unmistakably masculine and with such a strong private air that Linnet hesitated at first on the threshold. Then, however, she marched to the window, stretched across a worn, comfortable couch, pulled the curtains apart and pushed the window open with exaggerated force to document the legitimacy of her being here, albeit not seeking it.

“Thank Goodness, there are no plants as well!” she said, being both angry and thankful all at once.

The only item of note was a pegboard that took up almost an entire wall and displayed in pleasing arrangement all that the Marshalls had found on the island over time. Stones, various minerals, dried plants, shells, tiny sun-dried skeletons, butterflies and moths and much more. Except for an ancient flint knife, nothing was valuable on its own. But all together, as a glorification of the treasures of the earth, it was a treasure, for it betrayed the Marshalls’ love for this island from which it all came.

“Quite an achievement,” he thought.

Linette stood there like a statue. “I wonder if Marshall ever thought of displaying this at a fair?”

“You bet, Professor Restorick. He’s done it every year since they got the house here,” said a nasally voice in a dragging, familiar tone. “Brought it here a fortnight ago. Does the horse show too.”

Startled, they wheeled around, and caught sight of a skinny little man with a wrinkled neck leaning against the doorframe in dirty clothes, chewing on a straw. Although an obviously hard-working, well-off farmer, he looked like a wasp rat that had washed up years ago.

“I’m Professor Marshall’s caretaker. The name’s Alfred Stokes, from the village. Just wanted to see if ya had a safe arrival. My mare gave birth to a foal at the crack of dawn today, so I couldn’t air it out as usual. But I watered all the plants yesterday. If you need anything, you only need a call. Maybe there’s a problem with the bathroom in the hall. My son Tobias is an installer. He’s been working on it, but he’s not satisfied yet.”

His restless eyes, the lurking posture of his head and the impertinence of his tone and manner were in stark contrast to the friendly words. He gave the impression that he had been watching the two of them for quite a long time.

Linnet found him immediately unappealing. She was not unfamiliar with this type of person.

“Thank you, Mr Stokes,” Simon said, “that’s very thoughtful of you. I think we’ll get on quite well. Doctor Marshall gave me your telephone number. We opened the windows and had a look around.”

“Yeah, there’s a lot to see in this house,” the farmer agreed, and again Linnet heard a suggestive undertone. “Well, I’ll be off then.” He nodded to them, grabbed his old hat and disappeared as silently as he had come.

“What did he mean by that?”

“What do I know? Linnet, what’s the matter with you? He was just trying to be nice. The house is big...”

“So? You heard what he said? The Marshalls want to display the pegboard and be in the horse show, Simon. Will the Marshalls be here—with us? Did you arrange this? Without telling me? Then what did we go away for? We are not going to solve our problems that way.”

“It wasn’t fixed. Maybe they’ll come tomorrow afternoon,” he said evasively. “But what does it matter? After all, they’re only staying until Sunday afternoon or evening. We can’t expect them to go somewhere else when we're only taking one room anyway. We’re damn lucky...”

“Indeed? It doesn’t matter to me how long the Marshalls stay. I care about something else entirely!”

“For God’s sake, give me a break! It's just too hot.”

Her short, curly hair gave off red sparks, but her big grey eyes, otherwise so glassy, were now dark with tears. “Yes, of course. And it was too cold in January. Or you were too busy or too tired or something; for the last three years you’ve just always shirked everything! It’s a pity that most of what occupies you, what diverts your attention from us, is not exactly unimportant. Suppose it finally works out with the course in Africa? Or you want to try again in Oxford? Then you would have to go! But what do you value more, your career or our marriage? Ever since we’ve known each other, you’ve refused to see that you too have your faults. Every row, every mishap, it was all my fault. Always! What you remember about the accident is that I was driving the car. I begged you to stop somewhere because we were both overtired and I didn’t really want to relieve you at the wheel—but you refused. How was I, alone, supposed to pull you out of the car? Have you thought about that? And you think a fortnight—less!—in a summer house belonging to strangers would be enough for us? For the rent we pay here, and for the money we will still need here, we could afford extensive treatment...”

“Stop it. We don’t need no psychotherapist.” He unbuttoned his short-sleeved shirt and took it off, brushing it over the stump of his left arm with exaggerated care. He had had almost all his shirts and jacket sleeves shortened to make the mutilation visible. To keep it constantly in front of her, above all. He rarely wore the hook or the prosthesis. “What we have to do, we can do ourselves.”

“How? By paying for our quarrels here? Or for keeping each other quiet? We might as well have stayed at home and bought a new car. You don’t talk, you accuse! Everything has got worse, not better,” she said dejectedly. “I’ve asked you to forgive me, I’ve done everything I can to compensate you...”

“You’d have to make a hell of an effort to compensate me for this!” he shouted, holding out the stump of his arm.

This melodramatic scene was not new to her. “Like this?” she asked calmly. “What do you want me to do? I’m ready for anything.”

“What on earth has got into you? Are you going to throw away twenty-three years of marriage and the kids just because of a few arguments?”

“And you?”

“What are you talking about? Daisy and Hector...”

“Daisy and Hector are old enough to stand on their own two feet. Either we get treatment—together—or I leave you. Is that clear?”

“I’m going to unpack,” he decided angrily. “And we’ll use the guest room until the Marshalls have left. You are entitled to your own room. You can do what you like.” He stomped out.

She stood dejectedly for a moment and then, because she had no choice anyway, went out to the car to help him.

Frey lay on the cool steps, drawing in a whistling breath with every gasping breath, so they did not shoo him up. But it was very hot, and after Simon had stepped over him several times with his arm loaded high, he drove at him impetuously.

“Couldn’t you use your prosthesis for once?” she cried. “What’s the matter with you? You can see he’s not comfortable!” She yanked open a drawer of the dresser in the guest room while he opened the closet door.

“What are we going to do now? The drawers are full!”

“So is the wardrobe.” He took out an expensive, high-fashion suit. “Must be Graham’s—quite his size and style.