18,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

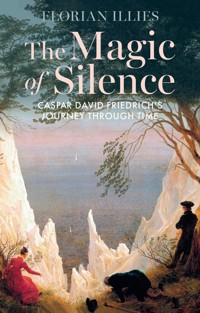

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

No German painter evokes such strong emotions as Caspar David Friedrich: his evening skies remain icons of longing, his mountain vistas testaments to the grandeur of nature. He inspired Samuel Beckett to write Waiting for Godot and Walt Disney to create Bambi. Goethe, however, was so enraged by the enigmatic melancholy of Friedrich’s paintings that he wanted to smash them on the edge of a table.

In a sweeping journey through time, bestselling author Florian Illies tells the story of Friedrich’s paintings and their impact on subsequent generations. Many of his most beautiful paintings were burned, first in his birthplace and then in World War II; others, like the Chalk Cliffs on Rügen, emerge from the mists of history a hundred years after Friedrich's death. Illies recounts the story of how Friedrich's paintings ended up at the Russian czar's court, others among a pile of winter tires in a Mafia car repair shop, and others still in the kitchen of a German social housing apartment. Adored by Hitler and Rainer Maria Rilke, despised by Stalin and by the generation of 68, this compelling narrative dances through 250 years of history as seen through Friedrich’s art and life. As a result, the man himself becomes flesh and blood before our very eyes.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 274

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Prologue: Aboard the Sailboat

Part I Fire

Part II Water

Part III Earth

Part IV Air

Acknowledgements

Chronology

Further Reading

Illustration Credits

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Prologue: Aboard the Sailboat

Begin Reading

Acknowledgements

Chronology

Further Reading

Illustration Credits

End User License Agreement

Pages

iii

iv

1

2

3

4

5

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

100

101

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

140

141

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

The Magic of Silence

Caspar David Friedrich’s Journey Through Time

Florian Illies

Translated by Tony Crawford

polity

Originally published in German as Zauber der Stille: Caspar David Friedrichs Reise durch die Zeiten. Copyright © 2023 S. Fischer Verlag GmbH, Frankfurt am Main

This English edition © Polity Press, 2025

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press111 River StreetHoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-6755-3

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2024944028

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:politybooks.com

Prologue: Aboard the Sailboat

It was a beautiful August day – the sun bright, the sea sparkling. The year was 1818. Early that morning, they had boarded the sailboat at Wiek on the island of Rügen, stowed their luggage and Friedrich’s paints, brushes and folding easel, and slipped out silently across the sleepy bay, past the pale green beech woods of Hiddensee Island to starboard, on a southward course for Stralsund. A warm wind blowing from the east, where Rügen’s rolling hills sheltered the grave mounds of aeons past, swelled their sails and tensed the lines. How he loved that moment when the great canvas sails suddenly snapped taut and then magically set the little ship in motion! Had the human spirit ever devised anything, he wondered, more beautiful than this? When he got back to Dresden, he would try to do with his brush exactly what the wind did with the sails: breathe life, invisibly, into the woven canvas. Caroline interrupted his thoughts: Look, Caspar, over there on the sand bar! Can you see the seals climbing up out of the waves? I’m sorry, darling, he smiled shyly, pardon me, I was completely immersed in my daydreams.

Never mind, she said, tenderly taking his hand. Thus lost in thought, they sat in the bow of the sailboat that was taking them back to the mainland. It was 11 August and they had just spent their honeymoon on Rügen: the peculiar 44-year-old artist from Greifswald and his 25-year-old bride from Dresden with the unruly brown hair, always pushing back one curl or another that fell in her face. But at the moment the obliging wind spared her the trouble, and she undid her hair, shook her head and let her hair flutter in the breeze. Later, before they sailed into Stralsund, she would pin it up again neatly with the blue flower that Friedrich, romantic that he was, had given her.

It was quiet on their sailboat. Sometimes they heard the shrieks and the heavy wingbeats of the gulls; from time to time a few salty drops of spray flew up and hung glittering for a while in Friedrich’s ginger whiskers. Caroline had never been on a sailboat before this trip. On the outward journey she had been quite anxious – but if they must drown, she would be happy to go down with him. Yes, she’d actually said that. Caspar David Friedrich could hardly believe his luck. How did I ever find you? he murmured, holding her hand as tight as he dared. ‘Love is a funny old thing’, he had written to his brother Christian, announcing his whirlwind marriage. Although she was a Saxon girl, he continued, Caroline had quickly acquired a taste for the Baltic Sea herring that Christian had sent them from Greifswald. Indeed, since Caspar had gone from an I to a we, quite a few things had changed in his Dresden home. True, he could no longer leave spittoons standing around waiting to be dumped out – she refused to get used to that – but otherwise, ‘There’s more eating, more drinking, more sleeping, more flirting, more lepschen.’ Yes, he wrote lepschen, whatever that meant; in any case they would be expecting their first child in the coming year.

They spent almost the whole day under sail crossing the glittering lagoon, the bright water changing between dark blue and turquoise. Friedrich couldn’t get enough of it, his artist’s eye absorbing the boats, the lines, the mast, the rippling sail, the shorelines to the left and right, the lush green of the trees that crowned the cliffs. As dusk slowly fell on that magical August day, the planking under them was still full of the sun’s warmth, and they needed no coats or scarves. Stralsund emerged like a mirage from the evening haze ahead. Caroline solemnly pinned up her hair. The spires of the city rose up out of the reddish twilight as their sailboat glided towards the port. A reverent yearning filled Friedrich and, he believed, Caroline too. Exactly this moment needs to be painted, he thought, and felt a fire swelling up inside him. Maybe – maybe this is the first time in my life I’ve really been happy – the water beneath me, the land ahead, the sky above, the air all around, my hand in hers.

Could we please, Caroline asked him suddenly, get something else besides fish to eat in Stralsund this evening?

PART I FIRE

On a balmy night in early summer, as the nightingales were singing their last songs in the lilac bushes, a delicate yellow tinge began to lighten the dark blue of the sky. Munich suddenly began to glow: glaring red flames leapt skywards from the colossal Glaspalast in the Botanical Gardens. The radiance of the fire lit up the façades of the nearby Sophienstrasse and Elisenstrasse, and the heavens seemed to flicker like a fireplace. The silence was torn apart by the cracking iron lattice and the shattering windowpanes as they crashed down into the inferno.

In the early morning hours of 6 June 1931, everything that Caspar David Friedrich had loved was perishing in the flames of the Munich Glaspalast: his painting of the rocky Baltic Sea Strand, the object of his undying homesickness; The Port of Greifswald, the wistful picture of his birthplace; the Augustus Bridge in Dresden, which he had seen every day out of his own windows; and, most painfully of all, Evening, the picture of his wife Caroline and their daughter Emma, looking pensively out of the window at a balmy night in early summer. The ravenous flames devoured the dry wood of the stretchers, leaving scraps of canvas to swirl up into the sleepy sky as little black swatches of ash, blown upwards again and again by hot swells of flame until they were lost to sight.

*

Because glass and steel are not flammable – obviously – the management company of the Munich ‘glass palace’ had decided in 1931 to economize, rather than renew the fire insurance that had been negotiated for the building on its construction in 1854.

*

Shortly after 3.30 in the morning on 6 June 1931, the telephone shrilled in Eugen Roth’s flat, just a hundred paces away from the Glaspalast. The editor of the Munich Neueste Nachrichten was on the line, ordering his local reporter to the scene of the burning Glaspalast immediately. Roth pulled his clothes on and, his fingers still befuddled with sleep, threaded a roll of film in his camera, with a glance at the two drawings by Caspar David Friedrich still slumbering on the wall above his bed. The light was dim, but he knew every blade of grass in those pictures: Roth was a passionate collector; he sacrificed every mark he earned by his pen to the city’s art dealers, and the god he worshipped was named Caspar David Friedrich. Before falling asleep every evening, he looked up briefly at that little sheet of paper with the scene of Saxony’s sandstone mountains, and longer at the silent, enchanted Baltic Sea Strand that Friedrich had drawn on Rügen.

Roth had been to the Glaspalast just the previous week for the gala opening of the exhibition of 110 ‘Works of the German Romantics, from Caspar David Friedrich to Moritz von Schwind’. One hundred and ten of the finest Romantic paintings ever gathered, on loan from the leading museums. And in fact he had been planning to go again this afternoon, on his Saturday off, to look and enjoy the pictures at his leisure. Now he was hurrying there twelve hours earlier than planned, already anticipating horror instead of enjoyment. The bells in the Church of the Trinity struck four as he picked his way, coming from Arcisstrasse, across the swollen hoses of the firefighters, thrusting his press card at the police officers. The sky above him was now dark red, and then he saw it: the Glaspalast, or what was left of it. Over its full length and breadth, a monumental 234 by 67 metres, the building was engulfed in flames, the heat pulsing against his face like glowing fists. Taking shelter in a doorway across the road, he took his pencil and notebook from his pocket – but he could not take his eyes off the horrible spectacle. In the early morning hours of this beautiful, terrible June day, Roth recalled each one of the nine paintings by Caspar David Friedrich now smouldering before his eyes: Evening, with the artist’s wife and daughter; the Port of Greifswald; the Bohemian mountain landscape. He thought of the poor man in the Autumn Scene, gathering sparse twigs on deserted fields to light himself a fire in the evening: now he and his bundle of wood were both drowned in the flames. And he recalled the picture he had liked best: the Lady at the Seaside, very tenderly waving a handkerchief after a departing ship. He could still see her salute; it had touched him deeply. Now he knew she was saying good-bye forever. The lady’s white handkerchief was now a flake of black ash; she would never again be seen in this world. Eugen Roth began to write to keep from crying: ‘The gaze wanders over the sea of fire. The tongues of flame lash upwards, roaring up like the tide, sinking back and surging up again, spraying sparks, flickering and snapping, cowering before the firefighters’ crushing jets, then rushing out again a thousandfold, tauntingly dancing and waving and whirling.’

Just a few hours later, Roth’s trembling eyewitness report appeared in the morning edition of the Neueste Nachrichten. The newsboys cried it in the narrow streets of Schwabing and in the broad square – shocked into silence that morning – of Marienplatz. Eugen Roth’s text painted a portrait of that fire with the detail of a Caspar David Friedrich: he saw every single flame, every reflection in the firmament, every seething, hissing wind – it was this text that made him the poet that he would remain in later years. Eventually, he had to leave off writing in the rain of ashes, unable to stand the desperate pigeons flapping through the smoky air, flying oblivious into the sea of flames – suddenly Roth understood that they were looking for their nests in the angles of the iron latticework, where their young, just hatched, had been sleeping peacefully under their wings an hour before.

*

And how did Thomas Mann experience the disturbing glow of that Munich night, the devastating fire in the wee hours of that 6 June that happened to be his fifty-sixth birthday? Did he complain to his wife Katia about the fire department making such a needless noise? Or about the disagreeable smell of smoke ‘affecting’ his nose? Did he go to look at the scene of the fire? We do not know. We only know that he gave a lecture at the university in July as a fundraiser for the victims of the disaster. And that he wrote a little later, in his novel Lotte in Weimar, of Adele Schopenhauer gushing over the ‘divine David Caspar Friedrich’. This is all we know because Mann’s diaries of 1931, which might have recorded his reactions to the conflagration of the treasures of Romantic art, were themselves unromantically burnt by their author in 1945 in the backyard of his house in Pacific Palisades, California.

*

Adolf Hitler and his half-sister’s daughter, Geli Raubal, with whom he had shared a flat at Prinzregentenplatz 16 in Munich for two years – the rent financed by the royalties from Mein Kampf – were startled out of their sleep by the sirens of the fire trucks screaming all through the city. The fire trucks rushed to the Botanical Gardens from all parts of Munich as the citizens tore open their windows and looked in the pale light of dawn towards the city centre and the giant plumes of smoke being blown by the wind as far as Schwabing.

Hundreds of sleepy, distraught people were in the streets, torn between fear and curiosity. The first rays of sunlight to lighten the sky were oppressed by the clouds of sooty ash and the red reflections of the fire. When Hitler arrived in the square at Stachus, he saw that the gigantic glass palace, the city’s diadem, thought to be fireproof, had been transformed into one great boiling sea of flames, its thousands of panes of glass shattered and its iron beams looking like a gigantic, blackened spiderweb jutting up irregularly out of the fire. The crowns of the tall linden trees around the Glaspalast rustled frantically in the wind induced by the fire, their pale green leaves seared and curling in the heat. Just a few days before, Hitler had visited the big exhibition of German Romantics, the most sumptuous compilation from the collections of German museums in decades, here in the Glaspalast. But now all 110 of these irreplaceable paintings – by Runge, Friedrich, Schinkel and more – had been taken by the flames, destroyed, stolen from the cultural memory forever. Hitler felt an irrepressible anger. He promised himself that here, in the city where this disastrous fire took place, he would build a temple to German art, a Haus der Kunst, that would stand forever. And so it happened. And three months after the appalling fire at the Glaspalast, on 18 September 1931, Hitler’s niece Geli Raubal, aged 23 years, would fire a lethal bullet through her lung in the flat they shared, whatever their relationship may have been, at Prinzregentenplatz 16.

*

Caspar David Friedrich was playing with fire. He was constantly drawing human figures even though he was no good at it at all. They had ridiculed him for it at the Academy in Copenhagen, and now in Dresden they were making fun of him again. Life drawing: he just couldn’t get the hang of it. His nudes’ legs were always too long and their torsos flabby. ‘You’re the greatest life-draughtsman here’, the painter Johann Joachim Faber jeered as they sat side by side in the Dresden Academy. ‘I mean, the longest life-draughtsman.’ Friedrich’s eyes flashed angrily through his ginger lashes. If Faber only knew. The Saxon women, broad as their Saxon dialect, ought to be glad to be drawn a bit taller. But such witty ripostes only occurred to him when he was writing letters to his brothers. Faced with the naked young ladies in the life drawing sessions at the Academy, his humour abandoned him. He could not look at them for long; they made him feel dizzy and he had to look away. No wonder, then, that their arms and legs tended to get quite lengthy. Ah, people, he thought: people are so strange. And the women strangest of all. If they were trees, he would know what they were feeling. Then he would be able to gaze at them for hours and paint them in elaborate detail.

It was the year 1802 and the peculiar young man from the Baltic coast, a beanpole with ginger side whiskers and a sluggish gait, had taken modest lodgings in the widow Vetter’s house in Festungsgraben, Dresden. He called her ‘madam’ and her adolescent daughters ‘mamsells’, but the girls were mortally insulted nonetheless because he never spoke to them, never took them for walks, and never tried to win a flower for them in the shooting galleries at kermesse time. If he ever did manage to open his mouth, he cramped up, his pale face flushed, and he couldn’t get a word out. He was glad on days when he didn’t have to say more than ‘good morning’ and ‘good evening’ – or, better still, when he could get by on the lovely Saxon word he had learned in Dresden: ‘Nu’. One syllable that fit every occasion. More a sigh than a word, almost.

So he sat one winter night in his austere room by candlelight. The landlady and her daughters were finally asleep. He was wearing a fur coat against the cold; his family had sent it from the North to help him survive in far-away Saxony. And the candles were from back home too: straight from his parents’ house in Greifswald, where his brother helped his father dip them in the little tallow-boiler’s shop behind the cathedral. His father had wanted Caspar David to learn the trade too, but he was too clumsy, always burning his fingers. So now, instead of drawing the long tallow candles, he was drawing the limbs of his figures long. His adaptation of the family tradition, perhaps.

Thus, on this gloomy winter evening in Dresden, Friedrich took up his engraving stylus and began scratching fine lines in a metal plate. He started, of course, with the trees, great linden trees in all their glory: that was something he knew how to draw. Before them, ruins. He could draw those, too; after all, he was a Romantic. But then he drew a crouching woman and a man with a hat, too tall, leaning awkwardly against a column. It was plain to see that their artist had serious trouble drawing them, but still didn’t understand what trouble the two figures had. The situation was explained only by the title: Friedrich called this disturbing print Man and Woman before the Ruins of Their Burnt House. The fire must have been some time ago, though, because there was neither glimmer nor smoke in the picture. In fact, the ruins of the house looked rather ancient, as if the fire had been a few centuries past. Man and Woman before the Ruins of Their Burnt House: why would a person draw such a depressing subject? And why would he then be surprised if no one wanted to buy it?

A few years later, Friedrich painted another burnt-down house. He couldn’t help it. This time in oil, and this time with fire. And smoke! The smoke covers the painting, making it dark and strange. Unfortunately, the setting is night as well: hardly anything is visible; it is an apocalyptic scene. Embers glow amid the blackened rafters of a burnt-out roof. Dark, spidery trees in the foreground are dimly lit by the fire. Above, a church, unscathed. This time, Friedrich left out the figures: he realized they did little to improve his pictures. But the painting is strange, nonetheless. There is no magic to it; something is missing. There is no sky.

A century later, on 10 October 1901, the house at 28 Lange Strasse in Greifswald, where Caspar David Friedrich was born, burnt down on a twilight afternoon. This time, the ‘man and woman before the ruins of their burnt house’ were Adolph Wilhelm Langguth, the grandson of Friedrich’s brother Adolf, and his wife Therese. The fire broke out in the shopfront and the old chandlers’ workshop in the front of the house around 5 o’clock in the afternoon, when the burner under a cauldron of floor wax ignited a canister of petrol, which exploded. From there the fire spread to the staircase and, ‘reinforced by the many flammable materials present’, consumed the upper floors. The newspaper the Greifswalder Tageblatt did not say what those ‘flammable materials’ were. By the time the firefighters’ first wagons arrived, speeding across the market square, the rear wing of the house was already alight. Dozens of firefighters sprayed the burning house unstintingly with eight hoses at once. The sky was aglow over Greifswald, the dark clouds illuminated in bright red. The firefighters could not enter the building or the narrow courtyard because of the heavy smoke; they could only douse it from outside, pouring water on the flames in a steady stream. In spite of their efforts, the front wing burned to the ground, and they concentrated on protecting the neighbouring buildings so that the fire would not spread farther in the narrow streets, or endanger the nearby cathedral. The result looked exactly like Friedrich’s engraving of the Burnt House: the charred rafters of the burnt-out roof in the foreground; behind it the old, serene splendour of the church.

Three hours later, the fire department had done all it could, and the wagons drove away. The whole city smelled of smoke and soot, and steam rose from the ruins where the house had been. The police had had to chase away the onlookers after one man and his teenaged son had wailed that they wanted a better view of the fire. According to the Greifswalder Tageblatt, their names had been written down.

But there was no record that nine paintings by Caspar David Friedrich were among the ‘flammable materials present’ in the upper storey of the rear wing of the house. By 1901, the painter had been completely forgotten in Germany: none of his paintings were exhibited in any public museum, and even among his family on the Baltic coast, he was known only as the quirky artistic ancestor who had fled their Hanseatic home town for Saxony because he was too clumsy to boil tallow and dip candles.

Only Alfred Lichtwark, the director of the Kunsthalle in Hamburg, realized the unique quality of the paintings by that family’s black sheep. In 1902, when he came to Greifswald for a second time to buy paintings for his museum from the descendants of the artist’s siblings, he was shocked:

Some of Friedrich’s paintings, fortunately not the best, had burned since I saw them the previous autumn. I looked for the house in Lange Strasse: there was a new building in its place. The owner took me up to the attic where the remnants were stored. There was nothing to be saved. The sight was moving. The frames and canvases were unharmed, but the paint itself had not withstood the heat.

After the fire, the pictures were covered with blisters and blackened with soot; the paint had cracked apart; the nine pictures looked like a lunar landscape, dark grey and sprinkled with craters. The Friedrichs that were destroyed were very particular, very personal pictures: the two portraits he had painted of his wife Caroline – one on the stairs, one with a candelabrum in her hand; then a picture of Neubrandenburg, his mother’s home town, with its Stargard Gate; and a dark green picture of the mossy sandstone canyon at Uttewald, where Friedrich had hid for six days as Napoleon’s troops were marching on Dresden. There was also a landscape of the Harz Mountains and one of Rügen; there was a ship off the beach at Greifswald and a view of the abbey ruins at Eldena, with the mighty oak trees Friedrich had loved. Nine pictures that amounted to an autobiography. Only one painting had not been saved from the fire at all: Caspar David Friedrich’s great self-portrait. It burned to ashes in the house where its creator had been born.

The family would eventually look for a way to rekindle the past radiance of the scorched paintings after all – and, apparently, that way had to be named Adolph. Adolph Langguth, the grandson of Friedrich’s brother Adolf Friedrich, sought the help of his cousin Friedrich Adolph Gustav Pflugradt, grandson of Caspar David Friedrich’s sister Dorothea. Because he not only shared the name Adolph and the Friedrichs’ ancestry, but was also a painter, Langguth gave the nine ruined paintings to Pflugradt, who brashly painted over them in bright colours, with no regard for their original quality. He pressed the many blisters flat with his brush to make his paint stick better in the holes. No one could say afterwards what had damaged the paintings more: the fire, or Pflugradt’s attention. In any case, these relics survived the First World War in no. 28 Lange Strasse without further detriment. The next owner of the nine ruined Friedrichs, an obscure great-grandson of the artist’s sister, went bankrupt – or, perhaps more fittingly: he crashed and burned. As a last-ditch scheme, he had put an advertisement in the Weltkunst: ‘Caspar David Friedrich paintings for sale’. But no one answered.

*

One of the paintings, however – namely, the dark Uttewald Canyon – found its way from the burnt-down house of the artist’s birth in Greifswald to Berlin. It ended up, fittingly enough, with Wolfgang Gurlitt, a colourful art dealer whose love affairs were a credit to the town’s Roaring Twenties, and who as an independent businessman knew a thing or two about being burnt out. He wagged his puppy-like charm in all directions. Gurlitt lived together happily with his ex-wife, his equally empathetic ex-sister-in-law, his new wife and their daughters, and the love of his life, Lilly Agoston.

No mean feat, even for the time.

Gurlitt’s women lived in varying combinations in two flats on the west side of Berlin, while he shuttled back and forth between them. As his lifestyle became too extravagant and his creditors sued, Gurlitt tried to save his business by publishing erotic portraits of his sometime lover Anita Berber, but that only brought him further legal action for distributing obscene publications, and in 1932 he was obliged to declare bankruptcy. Meanwhile, the badly damaged Uttewald Canyon hung on the wall in Gurlitt’s gallery in Potsdamer Strasse, oblivious to life’s vicissitudes, but no one cared to buy it. Perhaps one-fifth of it, to be generous, was still what had been painted by the master’s hand. But the rest – the dark browns and greens of the Saxon canyons – were by Friedrich’s descendant, Pflugradt, and various restorers, who had filled the broken blisters with paint until they had extinguished all the magic.

Nevertheless, Gurlitt guarded this picture like the apple of his eye. He even took it along to Austria, packed in a suitcase between his shirts, when he had to leave Germany on account of having a Jewish grandmother. In that way, he saved the Friedrich from a second, definitive death by fire, because his Berlin flat was completely destroyed by Allied bombs on the night of 22 to 23 November 1943.

By that time Gurlitt had moved, with his entire harem, his daughters, and his most valuable works of art, to Bad Aussee – where he lived, intriguingly, just a few hundred metres away from the salt mines where Adolf Hitler was hiding the most precious paintings of all Europe as he collected them for the ‘Führer Museum’ he was planning to establish in Linz. Among the treasures hidden there underground were works by Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Rembrandt, and the Ghent Altarpiece of Jan van Eyck. All of them would return to their original locations after the war. The halfburnt Friedrich, however, remained in Gurlitt’s house in Bad Aussee. As Gurlitt was evidently a man of great resourcefulness, who wandered adroitly not only between the ordinary pitfalls of life, but also through the Nazi period, he was able to offer his services after the war as director of a new art museum being founded in Linz. And, in fact, he got the job, without having to suspend his other business. In a daring stroke, Gurlitt the museum director bought the collection of Gurlitt the art dealer for the sum of 1.6 million marks. Thus Gurlitt finally sold the burned and hence unmarketable Friedrich to himself, for a handsome price: the Austrian state paid, and Gurlitt pocketed the money.

That, too, was no mean feat.

*

Whenever Caspar David Friedrich thought of his childhood and his origins, he always saw images of blazing fire and smelled the smoke and ash. The Bechly family of Neubrandenburg, his mother’s people, had been blacksmiths, and from his earliest childhood, little Caspar David had gazed in amazement at the coals that melted the metal of the horseshoes and steel fittings.

As a boy, he was once assigned to draw a Greek god from Preissler’s drawing manual, which his teacher Johann Gottfried Quistorp had given him. He chose Hephaistos, the god of fire, and drew him smiling with enjoyment. At the same time, in the cellar of his own family’s home at no. 28 Lange Strasse in Greifswald, the fire burned daily under the great tallow cauldron in which his stern father and his assistants boiled animal remains into soap, filling the whole house with a foul smell that disgusted Caspar David. He much preferred another smell from another cauldron where the wood fire kept wax melted so that his father and his brothers could dip candles.

Later, when he travelled, and his long days of wandering across country made him feel melancholy and lost, he would take from his rucksack a candle from home, and smell it. That made him feel a little better straightaway.

*

On arriving in Munich from Baden Baden on 7 July 1935, Walt Disney and his wife checked into the Hotel Grand Continental for a few days. Disney had come to the Third Reich to see how his animal creations had been compiled into a full-length programme for the Bavarian cinemas, subtitled In the Realm of Mickey Mouse