Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Herder Editorial

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Spanisch

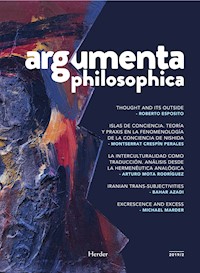

ARGUMENTA PHILOSOPHICA es una revista internacional de carácter científico y de investigación filosófica que se publica semestralmente y se dirige a un público universitario. Son temática primordial de la revista las disciplinas clásicas de la filosofía y su historia: metafísica, epistemología, lógica, ética, filosofía de la ciencia y de la mente, filosofía de la religión, estética o filosofía de la historia. Asimismo también acoge consideraciones teóricas sustanciales en relación a otras disciplinas humanísticas o relacionadas con ellas (psicología, sociología o antropología, por ejemplo).

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 251

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Editor

Dr. Raimund Herder

Jefe de redacción /Editor-in-chief

Dr. Miquel Seguró

Consejo de redacción/Editorial Board

Dra. Sonia Arribas

Teoría crítica; psicoanálisis (Universitat Pompeu Fabra)

Dra. Olga Belmonte

Filosofía de la religión (Universidad Pontificia Comillas)

Dr. Carlos Blanco

Filosofía de la ciencia epistemología (Universidad Pontificia Comillas)

Dr. Robert Caner

Estética; teoría de la literatura (Universitat de Barcelona)

Dr. Bernat Castany

Filosofia de la cultura; estética; teoría de la literatura (Universitat de Barcelona)

Dr. Juan M. Cincunegui

Ética; filosofía política (Universidad El Salvador, Argentina)

Dr. Alexander Fidora

Filosofía Medieval (ICREA-Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona)

Dr. Daniel Gamper

Filosofía política (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona)

Dra. Mar Griera

Sociología de la religión (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona)

Dr. Francesc Núñez

Sociología del conocimiento (Universitat Oberta de Catalunya)

Dr. Iván Ortega

Fenomenología; filosofía política (Universidad Pontificia Comillas)

Dra. Anna Pagès

Hermenéutica; filosofía de la educación (Universitat Ramon Llull)

Dr. Cristian Palazzi

Filosofía y ética contemporáneas (Universitat Ramon Llull)

Dr. Rafael Ramis

Historia del pensamiento jurídico, moral y político (Universitat Illes Balears)

Dra. Mar Rosàs

Filosofía y ética contemporáneas (Universitat Ramon Llull)

Dra. Neus Rotger

Teoría de la literatura y literatura comparada (Universitat Oberta de Catalunya)

Dr. Miquel Seguró

Metafísica; filosofía contemporánea; ética (Universitat Ramon Llull)

Dr. Camil Ungureanu

Filosofía política (Universitat Pompeu Fabra)

Consejo científico /Scientific Board

Dr. Roberto Aramayo

CSIC, España

Dr. Mauricio Beuchot

UNAM, México

Dr. Daniel Brauer

Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina

Dra. Judith Butler

University Berkeley, USA

Dra. Victoria Camps

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, España

Dr. Manuel Cruz

Universitat de Barcelona, España

Dr. Lluís Duch

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, España

Dr. Alessandro Ferrara

Università Roma-Tor Vergata, Italia

Dr. Miguel García-Baró

Universidad Pontificia Comillas, España

Dr. Jean Grondin

Université de Montréal, Canadá

Dr. James W. Heisig

Inst. Nanzan-Nagoya, Japón

Dr. Joan-Carles Mèlich

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, España

Dra. Concha Roldán

CSIC, España

Dr. Francesc Torralba

Universitat Ramon Llull, España

Dr. Ángel Xolocotzi

Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, México

Dr. Slavoj Žižek

Kyung Hee University, Seúl

Revista indexada en / Journal indexed in: Carhus Plus+, Dialnet, ERIH Plus, IBZ, IBR, Latindex, Philosopher’s Index y MIER

Cubierta: Gabriel Nunes

Imagen de cubierta: Agustí Penadès

Edición digital: José Toribio Barba

EAN: 9788425442681

ISSN: 2462-5906

Para suscripciones y pedidos

Herder Editorial

Tel. 934762640

http://www.herdereditorial.com/argumenta-philosophica

NOTA DEL EDITOR

La marca que va entre corchetes en color rojo [p. XX/XXX]

2/2019

Artículos

Thought and Its Outside5

Roberto Esposito

Islas de conciencia. Teoría y praxis en el fenomenología de la conciencia de Nishida21

Montserrat Crespín Perales

La interculturalidad como traducción. Análisis desde la hermenéutica analógic39

Arturo Mota Rodríguez

Iranian Trans-subjectivities. Trans body as a ‘territory’ between pathology and resistance51

Bahar Azadi

Excrescence and Excess63

Michael Marder

Reseñas

Anna Pagés, Cenar con Diotima. Filosofía y feminidad77

Julieta Piastro

Emmanuel Faye, Arendt y Heidegger. El exterminio nazi y la destrucción del pensamiento79

Olga Amarís Duarte

J.A. Estrada, Las muertes de Dios. Ateísmo y espiritualida83

Diego Solera

Eloy Fernández Porta, En la confidencia. Ensayo sobre la verdad musitada86

Anna Pagés

Martha Nussbaum, La ira y el perdón. Resentimiento, generosidad, justicia90

Marc Sanjaume

Libros recibidos95

Índice anterior103

Normas de Publicación105

Submission Guidelines110

THOUGHT AND ITS OUTSIDE1

Roberto Esposito

■ Abstract

The topic of this essay is the relation between philosophy and its outside. This ‘its’ has at least three meanings: outside from philosophy, outside into philosophy and outside of philosophy, up to the most extreme meaning of philosophy as the space of the outside. Placing myself on the margin that joins and disjoins them, I am going to refer essentially to three vectors, two of which are already classics to some extent, while another, more recent one, is awaiting further development. The thinkers I refer overall are Foucault, Deleuze and Nietzsche.

Keywords: thought, outside, Foucault, Deleuze, Nietzsche.

1. The topic of this essay is the relation between philosophy and its outside. This ‘its’ has at least three meanings: outside from philosophy, outside into philosophy and outside of philosophy, up to the most extreme meaning of philosophy as the space of the outside. Without being able to establish a clear limit between them —and, actually, placing myself on the margin that joins and disjoins them— Ishall refer essentially to three vectors, two of which are already classics to some extent, while another, more recent one, is awaiting further development.1 From any point from which we may look on our contemporary situation —on the sphere of power, as well as of knowledge, on the social dynamic as well as on the depth of material life— the issue of the outside has established itself at the crossroads between all paths. The very disciplines which are artificially separated by present-day devices of control and evaluation, actually progress due to their reciprocal contamination. It is not by chance that paradigm shifts within each of them are always produced by the encounter, or the clash, with another language, which forces their lexical limits from the outside and modifies their status. Concerning the relation between knowledge and power, in his celebrated Dedication of The [pp. 5/116] Prince, Machiavelli already argued that just as those who sketch landscapes place themselves down in the plain to consider the nature of mountains and high places and to consider the nature of low places they place themselves high atop mountains, similarly, to know well the nature of peoples one needs to be a prince, and to know well the nature of princes one needs to be the people.2

The light of knowledge that illuminates the inside —we may translate thus Machiavelli’s words— always comes from the outside, never the other way round.

The first reflection on this topic began with Foucault’s essay Maurice Blanchot: The Thought from Outside, published in the review ‘Critique’ in 1966, and later included in his Écrits.3 Through a close confrontation with the other great thinker of the dehors, Maurice Blanchot,4 he locates the lines of the outside on the border between philosophy and literature, separated from each other by a fundamental difference. Whereas for literature the relation with the ‘outside’ is constitutive, for philosophy this is a much more problematic relation as well as one which has not yet been considered substantially. It is true that the literary language seems to wrap around itself through an inner duplication that entails the designation of nothing other than itself —of becoming the same as its sentences, so that, for example, the proposition ‘I speak’ is absolutely the same as this other one: ‘I say that I speak’. There is no semantic gap between them concerning both the object that is spoken of and the subject that speaks. But the result of this wrapping of the word around itself, that seems to empower the subject of the discourse, actually produces its depletion, until it cancels its very stamp:

Literature is not language approaching itself until it reaches the point of its fiery manifestation; it is rather language getting as far away from itself as possible. And if, in this setting “outside of itself”, it unveils its own being, the sudden clarity reveals not a folding back but a gap, not a turning back of signs upon themselves but a dispersion. The “subject” of literature (what speaks in it and what it speaks about) is less language in its positivity than the void language takes as its space when it articulates itself in the nakedness of ‘I speak’.5

Enclosed in its literary self-referentiality, the sentence ‘I speak’ takes up the entire horizon of the speakable, dissolving everything that remains outside —context, objects, subjects. After all, in The Archeology of Knowledge, Foucault explained it as follows: unlike prepositions and phrases, that recall a subject with the power of inaugurating a discourse, the sentence takes roots in the anonymous being of language, preventing any ‘I’ from taking the word.6[pp. 6/116] In such a case the place of the subject is always empty; it coincides neither with the first nor with the second person of the interlocution; if at all, with the third —the person of the impersonal. Adhering to itself in a pervasive way, the sentence pushes to the margins of the scene not just what is talked about, but even the speaking subject. Failing any transitivity of the discourse, it is as if the subject of the word were swallowed by the pure function of speech. As is the case in modern literature, as soon as language sums up the entire story within it, “the subject that speaks is less the responsible agent of a discourse […] than a non-existence in whose emptiness the unending outpouring of language uninterruptedly continues”.7 Just as the visible finds visibility only in light, the sentence establishes its origins in the anonymity of language, before any I can take possession of the discourse. From this point of view, according to the laws of enunciation, the place of the subject is never replaced by an empirical or transcendental I; it is always empty, and thus open to names produced by the same sentence according to a logic which is external to any subjective appropriation whatsoever.

So, contrary to what it may seem at first sight, the self-referentiality of modern literature does not evoke an ‘inside’; it does not have to be interpreted as the result of a process of interiorization of meaning, but as emerging from it. The folding of language onto itself is the form adopted by its escape from the representative discourse and, before it, from the subject of the representation itself, towards an elsewhere from which it cannot return. As Foucault wrote in another text titled What is an author?, drawn from alecture at the Collège de France in 1960, “we can say that today’s writing has freed itself from the dimension of expression. Referring only to itself, but without being restricted to the confines of its interiority, writing is identified with its own unfolded exteriority”.8 The word of the word —within the circularity of a speaking I that says that it speaks— “leads us, by way of literature as well as perhaps by other paths, to the outside in which the speaking subject disappears. No doubt that is why Western thought took so long to think the being of language: as if it had a premonition of the danger that the naked experience of language poses for the self-evidence of ‘I am’”.9

Here lies the distance between literary writing and philosophical praxis. Unlike the ‘I speak’, the ‘I think’ produces the empowerment of the subject, not its evisceration —enough to lead to— in the classical Cartesian formulation —the indisputable certainty of its existence, to the cogito ergo sum. According to the dominant philosophical canon, the being of the subject is related to its thought, but it is precisely thought —the act of thought— which certifies the existence of the subject. It is actually possible to conjecture that it is literature’s threat to this status which determines the fact that [pp. 7/116] philosophy is reluctant to think the essence of language. It is almost as if philosophical reflection were fearful of the risk implicit in the literary experience for the ontological evidence of the ‘I am’. On the other hand, the very term ‘reflection’, always philosophically connected to self-reflection, that is, to self-consciousness, involves a movement of interiorization. The philosophical tradition teaches us that thought, due to its being thought, must become, like the God of Augustine, more intimate than our very own intimacy. Whereas in literature the word of writing pushes us into that outside in which the subject burns until it is consumed, the thought of thought constitutes its safeguard. It is a conviction that has the evidence of a truism: if it is already possible to say that it is language that speaks through us, he who thinks can be none other than the subject of thought. Whereas literature proceeds towards the outside, the philosophical tradition addresses the inside, always at the risk of enclosing itself in its self-celebration. That was what Adorno said critically, regarding the German ideology, and particularly Heidegger, when he spoke of the ‘jargon of authenticity’.10 It is as if thought had a sort of panic fear of emerging, of pushing itself outside of itself in the search for the non-conceptual element from which it originates and that it carries within it as an irreducible antinomic nucleus. The philosophies of the crisis of the early twentieth century, from Heidegger to Husserl, seem to be enclosed in this necessity of self-grounding that consumes itself, without hesitation, in the search for its Greek root.

Until something in this recursive mechanism cracks and gives birth, also within thought, to the necessity of breaking the glass in which the subject reflects itself in the intimacy of its consciousness. It is this forced entry that interrupts the self-referential circularity of philosophical language that Foucault defines as the ‘thought of the outside’. Anticipated by authors located at the borders of literature and philosophy such as, at the two opposite poles of modern sensibility, Sade and Hölderlin, this possibility found its first great interpreter in Nietzsche. In its disturbing genealogical path, he looks for the outside of thought in the uncontrollable power of life. Life is the absolute outside, because it stands inside us, but we are never able to direct her. She surpasses us, pushing us to where we often don’t want to be, or she lifts up us again after she breaks us down. Life is never really ours —if anything, we belong to life. This is what Nietzsche expresses with the concept of ‘force’, different and in some way opposed to that of ‘form’. If form seals the extension of an inside, force frees the unlimited space of the outside. As Deleuze wrote in his book on Foucault,

We must distinguish between the exteriority and the outside. Exteriority is still a form (…), even two forms which are exterior to one another, since knowledge is made from the two environments of light and language, seeing and speaking. But outside concerns force: if a force is always in relation with other forces, forces [pp. 8/116] necessarily refer to an irreducible outside which no longer even has any form and is made up of distances that cannot be broken down through which one force acts upon another or is acted upon by another.11

At the summit of this journey, Foucault places the faceless work —as is known, only a picture of it exists, faded in an opacity lacking light— of Maurice Blanchot. All of his writings —both literary and philosophical— seem to have in common a sort of preventive negation of his discourse, that has been deprived of its power of signification and reduced to a constant repetition that testifies to the definite disappearance of the subject of the enunciation. Starting from that moment —Foucault states— the discourse, enclosed within the essence of language, pulls itself out of its outside, listening not to what is said, but to the void that circulates in its words. Language, in Blanchot, is never spoken by anyone —the one that speaks each time just draws a grammatical fold in which the language founders and loses itself into nothing. It is said —in the third person— as Lacan will also state, outside of any control on the speaking subject. Blanchot’s writing does not respond to a need of signification, but keeps obsessively stating something that corresponds neither to an affirmation nor to a negation, but instead to a naturalization of meaning. An anonymous murmur that evokes the impersonality of a life that is not under the sovereign control of the subject. If inMallarmé’s poetry the word coincides with the existence designated by it, in Blanchot the essence of language determines the cancellation of he who speaks. As he says in a passage of The One Who Was Standing Apart from Me, quoted also by Foucault, that could constitute the emblem of the thought of the outside,

Saying that I hear these words would not explain for me the dangerous strangeness of my relations with them. They do not speak, they are not inside; on the contrary, they lack all intimacy and lie entirely outside. What they designate consigns me to this outside of all speech, seemingly more secret and more inward than the inner voice of conscience. But that outside is empty, the secret has no depth, what is repeated is the emptiness of repetition, it does not speak and yet has always been said.12

Foucault’s entire production can be interpreted under the sign of exteriorization. It is as if the canon of Western knowledge had everted itself, distancing itself from itself and making its traditional parameters rotate around themselves. The History of Madness can already be read as a critical revision of the logos setting out from its external margin, actually constituted by the madness that it has expounded by itself, confining it to an outside without return. But the humanities —starting with Ethnology— to which the last section of The order of things is devoted, produce a distortion of perspective which is even more charged with [pp. 9/116] deconstructive effects. Unlike the usual praxis of ethnological knowledge on other peoples, Foucault applies it to our conceptual universe, submitting it to the test of the outside. As sciences “they are directed towards that which, outside man, makes it possible to know, with positive knowledge, that which is given to or eludes his consciousness”.13 What is at issue here is literally the reversal of perspective that turns the subject into the object of a knowledge about what is still hidden at the bottom of our culture, displacing, so to speak, the perspectival axis from the West to the East, from the North to the South, of our individual and collective experience.

2. If Foucault looks for the ‘outside’ in the external boundaries of philosophy —where it borders on literature— Deleuze and Guattari locate it within them. After all, the term ‘geo-philosophy’, coined by them, is part of an interrogation which intended to define ‘what is philosophy’, the title of their last book. Philosophical research coincides with the research of its outside, in the double sense that only from the perspective of philosophy is it possible to interrogate its outside, but also that the essence of philosophy can only be grasped from the perspective of the outside. Even in such a case, like Foucault’s, their point of departure is a contrast —the contrast between history and geography— without, however, establishing a real opposition between them. If philosophy is geo-philosophy, then history too, considered in its material kernel, is also geo-history. Just as Ferdinand Braudel asked why capitalism was born in the West and not elsewhere, so thought is marked by the places it traverses, by the landscape it touches upon, by the environments it encounters. Actually, geography doesn’t merely confer a material spatiality on history, but opens it to an unprecedented interrogation and submits it to the novelty of unpredictable events: geography —Deleuze and Guattari write— “wrests history from the cult of necessity in order to stress the irreducibility of contingency. It wrests it from the cult of origins in order to affirm the power of a ‘milieu’ […] It wrests it from structures in order to trace the lines of flight that pass through the Greek world across the Mediterranean. Finally, it wrests history from itself in order to discover becomings that do not belong to history even if they fall back into it”.14

So, the transfer of philosophy under the banner of geography does not aim to substitute space with time, but to think of time spatially by focusing on the concept of becoming. But what is becoming? What should we understand by this term that plays a crucial role in the entirety of Derrida’s thought? For him, becoming does not just concern the chronological relation between before and after —just as, for example, ‘becoming an animal’ means to understand the emergence of man from an [pp. 10/116] anthropocentric model and coming to terms with what stands outside the limits of his species. As explained in A Thousand Plateaus, against the immunitarian tendency to enclose oneself within the limits of one’s species, becoming an animal means plurality, metamorphosis, contamination. Once again, that is nothing other than the outside that inhabits us: “We do not become an animal without a fascination for the pack, for multiplicity. A fascination for the outside? Or is the multiplicity that fascinates us already related to a multiplicity dwelling within us?”.15 From this perspective, the trajectory of becoming exceeds the pure historical dimension. Of course, without history becoming would remain indeterminate, but this does not mean that it belongs to it. Rather, as Nietzsche grasped in his On the Use and Abuse of History for Life, becoming can be considered the non-historical element of history.16 Something, inside history, that cannot be understood in historical terms, according to a development that links the future to its past. Neither does it refer to the present, but, if anything, to what Deleuze defines as ‘actual’ in an oddly similar manner to what Nietzsche meant by ‘inactual’: “The actual is not what we are but rather what we become, what we are in the process of becoming —that is to say, the Other, our becoming-Other”, whereas “The present, on the contrary, is what we are and, thereby, what already we are ceasing to be”. In this sense, the actual is never present. Rather, in some way it constitutes its other side, the one that always projects it outside of itself: “It is not that the actual is the utopian prefiguration of a future that is still part of our history”.17 This is even more valid for philosophy, that cannot be reduced to the infinite recognition of its own history, and that rather “continually wrests itself from history in order to create new concepts that fall back into history but do not come from it”.18 The relation between history and philosophy is not the mere sequence linking a series of authors and paradigms within a single flux, as the manifold histories of philosophy afflicting us may lead us to believe, but is traversed by events with a unique historicity that are incomparable to any others. What disappears is not just the continuity of one block of ideas, but also its inner character, its elicitation of its own interior. Against those that search for the meaning of thought in its proximity to itself, in its interior continuity, Deleuze and Guattari locate it in what elicits it from the outside, in the obstacles it encounters, in its limits and hindrances. Thought is not born from a folding onto itself, from an immersion in one’s own interiority, from an inner demand, but rather from an external pressure capable of overcoming the resistance, the illnesses, the inertia, weighing on it from the inside: “We [pp. 11/116] search for truth only when we are determined to do so in terms of a concrete situation, when we undergo a kind of violence that impels us to such a search”.19

Thought finds the tools to recognize itself only outside it. Its constitutive dimension is not the inside, but the outside. Naturally, inside and outside do not have to be separated into two opposite polarities —even if only because only if there is an inside can there be an outside and vice versa. Deleuze and Guattari translate the relation between outside and inside into the dialectic of earth and territory. “Thinking —they write at the beginning of their text— is neither a line drawn between subject and object nor a revolving of one around the other. Rather, thinking takes place in the relationship of territory and the earth”.20 What does this mean? How should we interpret these two detached and connected poles? If territory tends to redirect what is outside towards the inside of its own limits by territorializing it, the earth refers us back to the opposite movement, deterritorializing what has been territorialized. What matters, for the authors, is their indiscernibility. Earth and territory are not only contemporary, they produce each other. To confirm this, we may look at the experience we are going through in these last few years, in which the dynamics of globalization are producing new identitarian closures as a reaction, and these, in turn, are producing global effects.

The history of philosophy itself can be seen as the always provisional result of this dialectic. Every metaphysical system, in this respect, must be thought of as the territorializing impulse that responds to a previous deterritorialization. Even if it is impossible to say which of the two impulses precedes the other one, given that they are simultaneous, it still must be recognized that at the origin of what we have learnt to call philosophy the drive towards the outside seems to prevail over the tendency to return to itself. Despite the classical Hegelian interpretation that sees in Greece the first self-appropriation of the spirit, its main characteristic is its external structure. Far from being born from itself, Greece was originated in the encounter of previous civilizations —Carians, Lydians, Phrygians, Phoenicians. A diffuse, fractal, dispersed entity. And, above all, a maritime one, given that every point of the peninsula is equally close to the sea. Therefore, its cities, “rather than establish themselves in the pores of the empire, they are steeped in a new component; they develop a particular mode of deterritorialization that proceeds by immanence; they form a milieu of immanence”.21 It is also true that Greece, in order to withstand the collision with the Persian Empire, territorialized itself, but it did so in a specifically seaward way, thus making the sea no longer a limit to its territory, but “a wider bath of immanence”.22 According to Deleuze, to think means to tend towards an immanent plane capable of [pp. 12/116] absorbing and multiplying the earth, tearing it from its roots and projecting it towards the exterior. To expose the stability of the earth to the vertigo of the outside. Such an externalization does not exclude a later territorialization, but the latter always takes the form of a survey of a new earth, of a future earth, of an earth yet to come, and, actually, in the sense mentioned before, of a becoming.

The metaphysical tradition —as well as its supposed deconstruction— betrayed this double movement, as well as the promise of a new earth that it carried within itself. The Hegelian interpretation of Greece as the original locus of what pertains to its self —the marginalization, or the exclusive inclusion, of its foreign, heterogeneous element— already constitutes a first closure of what, nevertheless, makes our tradition open. Despite an apparent deviation, Heidegger reinforces this re-appropriative tendency, making every notorious expropriation functional to it: “He views —the authors write— the Greek as the Autochton rather than as the free citizen […]: the specificity of the Greek is to dwell in Being and to possess its word. Deterritorialized, the Greek is reterritorialized on his own language and its linguistic treasure —the verb to be”.23 Deleuze and Guattari conclude that the truth is that, regardless of their apparent opposition, both Hegel and Heidegger, confronted with the measuring rod of geophilosophy, remain historicists inasmuch they “posit history as a form of interiority in which the concept necessarily develops or unveils its destiny”.24 In the Husserl of Krisis, too, Greece is conceived of as the abandoned origin that the European Spirit has to find its way back to if it wishes to recover its meaning. We already know what a self-contradictory outcome this forcible reterritorialization of the Greek root, transposed onto German nationalism, came to. Deleuze and Guattari do not mince words when speaking about Heidegger: “He wanted to rejoin the Greeks through the Germans, at the worst moment in their history: is there anything worse, said, Nietzsche, than to find oneself facing a German when one was expecting a Greek?”.25

The other great dialectic that links territorialization and deterritorialization is the modern one, the dialectic obtaining between capital and State. As we know, capitalism, since its prehistory in the sixteenth century, has become the most powerful motor of deterritorialization, now that it has globalized the market. This outcome already indicates the ambiguous character, both affirmative and negative, of every process of encroachment —not all de-territorializing processes are positive ones per se. Not to mention deportation, even forced migration is a process of deterritorialization, as Simone Weil stated in The Need for Roots.26 This negative, exclusionary effect of deterritorialization takes place when new and deeper internal boundaries are inscribed within it. [pp. 13/116] And, in fact, present-day globalization responds not to a global democracy, but to the reterritorialization of Nation-states, that is needed, in the age of imperialism, to secure the expansion of their markets throughout the world.

For Deleuze and Guattari the relation between modern philosophy and capitalism is no different from the one obtaining between ancient philosophy and Greece. Furthermore, in this case, the impulse towards the outside has to be counterbalanced by a national center of gravity, according to the dialectic that Carl Schmitt traced back to the new Nomos of the earth, as a process of inscription and distribution of global power.27 So, even modern philosophy has to found itself anew on Nation-States and the spirits of the different peoples. It is an ambivalent process, open on one side and closed on the other. Deleuze and Guattari hastily sketch its features and separate the destiny of English, French and German thought from Italian and Spanish thought. Without necessarily sharing their judgement, quite reductive regarding Italian thought, what matters is the connection that they establish between globalization in its beginnings and the return to philosophies related to a space, which, if not national, is at least territorial. They state that every time that philosophy re-territorializes itself, it does so conforming to the spirit of a people, absorbing its national, if not nationalistic, features. After this brief survey of national philosophies, Deleuze and Guattari reintroduce the question of becoming, intended as the “non-historical storm cloud” of history.28