7,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 7,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 7,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: EDITION digital

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Deutsch

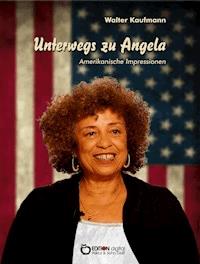

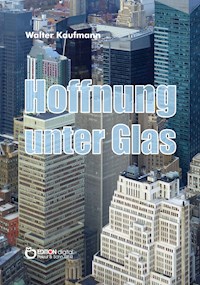

This is the story of one man’s impression of life in the Great Society. Foot-loose and fancy-free he follows the lead of his insatiable curiosity, taking the armchair traveler on a memorable junket. The book is no Baedeker. From his arrival (when he winds up in a hotel that has been freshly raided as a place of questionable repute) until his last backward glance at Kennedy Airport (as his home-winging plane rises for its trans-Atlantic flight), the days and nights of his journey are filled with adventure, people, humor and heart... For whether he is exploring the canyon which is Wall Street, or the dusty and treeless playgrounds of Harlem, whether he braves the swirling traffic of a well-regulated metropolis, or the back lanes of a Southern town gone mad with lynch spirit, his story of the American Way moves swiftly — and with a forthrightness that will charm the reader. He narrates his American Encounter with an open-minded freshness and with a sharp eye that penetrates the smog of big-city living and big-city headlines.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 169

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Imprint

Walter Kaufmann

American Encounter

ISBN 978-3-95655-292-2 (E-Book)

The book was published in 1966 by Seven Seas Publishers, Berlin.

Cover: Ernst Franta

Foto: Barbara Meffert

© 2017 EDITION digital®Pekrul & Sohn GbR Godern Alte Dorfstraße 2 b 19065 Pinnow Tel.: 03860 505788 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.edition-digital.de

ABOUT THE BOOK

This is the story of one man’s impression of life in the Great Society. Foot-loose and fancy-free he follows the lead of his insatiable curiosity, taking the armchair traveler on a memorable junket. The book is no Baedeker. From his arrival (when he winds up in a hotel that has been freshly raided as a place of questionable repute) until his last backward glance at Kennedy Airport (as his home-winging plane rises for its trans-Atlantic flight), the days and nights of his journey are filled with adventure, people, humor and heart... For whether he is exploring the canyon which is Wall Street, or the dusty and treeless playgrounds of Harlem, whether he braves the swirling traffic of a well-regulated metropolis, or the back lanes of a Southern town gone mad with lynch spirit, his story of the American Way moves swiftly — and with a forthrightness that will charm the reader. He narrates his American Encounter with an open-minded freshness and with a sharp eye that penetrates the smog of big-city living and big-city headlines.

MANHATTAN SALUTE

Morning

Foreword

To the brooding calls of foghorns the giant ocean liner slides past the Statue of Liberty northward into the mouth of the Hudson. The churned-up river laps against the hulls of freighters moored to the wharves of Manhattan and Jersey City. Cranes screech as cargoes are hoisted from the holds: Coffee from Brazil, rubber from Sumatra, bananas from Costa Rica... Invisible ferries scuttle tooting toward Hoboken and Weehawken. Gradually the silhouette of the liner disappears in the fog, her eerie hooting swelling the clamor over the water front, intensifying the expectancy of most everyone aboard — the Negro musician returning from Paris, the migrant toolmaker from Dortmund traveling steerage, the Swedish professor of sociology, the American millionaire’s widow homing to her suite in the Waldorf-Astoria....

Beyond the embankments of New Jersey, way out on land, express trains out of Waco, Mobile, Los Angeles, Kansas City, pound wailing across the fog-shrouded country, Manhattan-bound all of them as west of the Hudson they roar into tunnels deep under the river till they emerge amid towering skyscrapers on the last lap of their journey — Grand Central Terminal and Pennsylvania Railroad Station. Soon now the young aspiring writer from Gary, the prettiest actress in the Erie dramatic club, that rural bank clerk heading f or W all Street, the hope fid mechanic from Buffalo, will disperse — newcomers among untold thousands of others — through that vast glass and concrete maze of buildings in the heart of the city.

All over Manhattan weary nightworkers, watchmen, waitresses, printers, hostesses, dockers, subway cleaners, postal employees... are returning home. A water wagon rolls by. Bands are still playing in a dozen nightclubs. In the Upper East Side, in the Upper West Side, around Union Square, in Chelsea and Greenwich Village, the harsh, relentless ringing of alarm clocks shocks the ear. Sleepers wake. Another day, another dollar. Don’t forget to send my suit to the cleaner’s and drop by at Macy’s for a couple of shirts from the bargain sale —

The crowd increases with the light. Work-bound on buses and on subway trains a million people, two million, three ... stream through the city — the faces of New York: Italian, Mexican, Jewish, Negro, Irish, German, Puerto Rican ... footsteps on granite, high heels, low heels, the sound of feet merging with the swelling roar of the traffic. Toward the leaden sky an airplane rises, veering westward, wing tips slicing the lifting fog. Below the earth, speeding subway trains sway and thunder on steel rails, rocket through the tunnels — Crosstown from Queens, Shuttle to Times Square, Broadway Line to South Ferry — the length of Manhattan within the course of a minute hand. Grab a cup of coffee and run! Breakfast between trains. Outside, on Fifth Avenue, the girl’s voice is lost in the roar of traffic: He took me to the Rainbow Room; it got so late, we had a time of it finding a taxi. . . is lost in the squeal of car-brakes.

The morning sun reveals the pinnacle of the Empire State Building, the heights of Rockefeller Center, the Chrysler Building, Pan American’s helicopter port over Grand Central. Now the upper stories of hotels and apartment houses on Park Avenue'*are fringed with light, the morning sun reflects in a million windows, filters through obscure skylights of lofts. Down in the street canyons the people still scurry in a twilight, hasten into the buildings as if escaping the traffic, crowd the elevators that soar to the loth the 1,0th the both floor — then down nonstop in seconds. Inside an office sixty young women secretaries take off the covers of sixty typewriters. These shoes are killing me, she says, sitting down. Did, you read about the air crash? Why do people take those things — but how else can you get there fast?... The windows shake with the boom of a )et plane — or is it a terrestrial blast where that ancient warehouse is crumpled to make way for — what? borne store, another hotel, a bank, an insurance company ....

In Harlem, not a block east of Eighth Avenue, in 12th Street, the Negro musician tarries outside the Apollo Theater, inspects the photos of performers in the showcases, studies the cast, wonders bozo best to impress the white management later — ten years in Paris seems almost a lifetime suddenly: New stars have soared into prominence, new names, will they give me an audition?

The migrant toolmaker from Dortmund has reached Yorkville at last, struggled with his fiber suitcase away from Central Park across Lexington, Third Avenue, Second Avenue toward the east end of 86th Street. At odd, moments he seems transplanted home again — his surroundings a curious mixture of New York and Dortmund; the row of low and ugly brownstone houses ends at a corner pub, very pointedly, very old-fashionedly German in appearance: Heidelberger Fass; another Kneipe: Im Kühlen Grund, displays German beer mugs in the window. German newspapers are laid out in the newsstands. Gothic lettering marks the fronts of delicatessen stores—Schafer’s Delicatessen — Bockwurst, Mettwurst, Leberwurst, Knackwurst, Blutwurst on the clean, tiled display counter. Further along, a music shop: Deutsche Schallplatten. Hansa Lloyd Reisebüro: Photos of Bavarian mountain- scapes, castles on the Rhine... He puts down his suitcase, asks for directions in German. Now wait a minute, Buddy, l don’t dig that language. Go ask some Kraut, will you!

The Swedish sociologist has not left the ocean liner yet — in one of the ship’s lounges he is facing correspondents from The Nation, The New Republic, The National Guardian. It isn’t my task to probe the verisimilitude of the finding that some single individual like a Lee Oswald assassinated the President, he explains in impeccable English. That will have been decided. What 1 am concerned with is the moral and social climate that facilitated the tragedy ....

The widow of the millionaire is trying vainly to sleep in her suite in one of the towers of the Waldorf-Astoria. The maid is drawing the bedroom drapes across the tall windows, obliterating the sunlight, the view to the garden terrace, muffling to a whimper whatever city sounds rise to the height of six hundred feet — quietude! The light is dim. Will there be anything else, Madam? she asks. No, my dear. It has all been a little too much for one morning. I´m dreadfully tired, worn out. I just can’t face anyone or anything, not yet, anyhow, not for the next few hours ....

1. Chapter

Mr. Becker, having declared his profession, is asked what kind of an author he is.

“I write novels and short stories."

"And politics?”

“Not at all,” he replies, smiling.

With that he may proceed toward the Landing Hall - and into America.

Egon E. Kisch : PARADISE AMERICA

This author (he won’t attempt to hide his identity behind a pseudonym) was asked no such questions when, on a cold Wednesday in February, he confronted the gentle voiced, elderly Immigration Officer at John F. Kennedy International Airport, New York. His passport was in order and so was his American visa. Yet he had forebodings. Would he be turned back at the last moment? He had come as more than a tourist: Events in Viet Nam and Mississippi had prompted his journey, and although he did not propose to write specifically about any one subject, he did intend to report on life in America as he found it.

“What’s the purpose of your visit?” the Immigration Officer asked.

“A short stay in the States,” he answered noncommittally.

“About how long?”

“Perhaps a month.”

A closer inspection of his visa revealed that it would expire before then — but America accepted him with equanimity. The Immigration Officer merely advised him to have his visa extended at the earliest opportunity; it was always good to make provisions for eventualities — like sickness and so on. And for further travels.

With that he was permitted to proceed toward the Customs Room where presently his suitcase came sliding down a chute. Ingeniously contrived trolleys were available to wheel his luggage to a conveyor belt which transported it further toward an exit. Here, after the briefest inspection, he was dismissed into a huge hall — a veritable fair of commerce with glaring advertisements, shops, newsstands, exhibitions, tourist offices, information desks and airline counters, all crowded with travelers. Innumerable doors led in all directions, elevators soared to upper stories and moving staircases vanished into basements. Yet, more expediently than he thought possible, he found himself in the open amid fleets of taxis and rows of buses:

Welcome to New York, you stranger, travel around and be impressed!

He mounted a bus and minutes later the utopian aspects of the airport with its control towers, roaring tarmacs, its feverishly busy and vast areas of modern constructions, its winding roads and crowded parking lots, receded behind him. Manhattan-bound, without fixed plans, he concentrated on the immediate — which precluded the slightest notion that he should be returning here within a fortnight to make his way through a labyrinth of passageways (“follow the green light — follow the ted ... insure your life for a dollar ...”) to a point where an airplane would be starting with connections to Louisville, Kentucky.

In Louisville, having come down with a raging toothache that threatened to delay him indefinitely, he had occasion to remember with gratitude the first American he spoke to on American soil — that solicitous Immigration Officer who trusted him to behave as predictably as any other in a million tourists ....

But our author is getting ahead of himself. It would seem that he had best decide on relating his varied and manifold experiences in the United States in chronological order.

Newsreel

Three Negroes were wounded by buckshot blasts as police put down an eruption... Jack Ruby’s lawyer plans another test of his client’s sanity ... Money is what it can buy — clothes, food, cars, insurance. Or more money... Negroes rolled in the streets in front of paddy wagons, cops hustled demonstrators off to jail, and whites and Negroes cursed and battered each other with their fists... John Fitzgerald Kennedy 14K Gold Charms ($10.95 upwards) are a lasting tribute to a great president. We will mail for you — Charm & Treasure, 1201 Avenue of the Americas, N.Y. 36 N.Y.... Augustus Paino, the 19-year- old assistant scoutmaster stabbed to death by Salvatore Ortiz, 16, leader of the Miracle Diamonds, was known as a gang buster... John F. Kennedy Memorial License Plate, now obsolete, carried his famous quote: “Ask not what your country can do for you. Ask what you can do for your country” ....

Along an expressway the bus is heading through an unspectacular, often drab suburbia which for long stretches lies obscured by billboards depicting smiling goddesses of commerce with Ekbergian bosoms. Giant lettering spells out boastful superlatives. The bus skirts the World’s Fair Grounds dominated by the skeleton of an enormous globe, then rolls, its heavy tires beating the concrete, through the now denser traffic toward the western part of what I am discovering to be the borough of Queens — an industrial landscape to the right, an oily creek swarming with all manner of craft to the left, and in the distance, way ahead, huge bridges spanning a river. Suddenly the bus plunges into a tunnel and the brief view of the island of Manhattan, to a skyline of tall buildings aglow in the sunlight beyond the eastern water front, vanishes like the vision of a dream: It is as if some supernatural wrath had caused the earth to engulf the city. The bus speeds on and the faces of the travelers are discolored now in the yellow, eerie light of neons. The engine roar reverberates against the walls of the tunnel and the sound does not soften until the bus emerges at the East Side Airline Terminal on First Avenue.

Directed to a moving staircase that takes me to a basement under the crowded building, I find myself wondering where the Negro porter in the red cap has disappeared to with my suitcases — the possibilities seem unlimited. I light a cigarette, then, following the example of the waiting crowd around me, I pull a ticket from a slot machine. The ticket, it seems, gives me an option to one of the many taxis which, like vultures out of the light, are dashing down the drive into the cellar. The line diminishes. Soon it will be my turn. But of what use is transportation to me while I am deprived of my luggage? Besides, I do not know where I am headed. First things first, I am thinking when, with relief, I spy the porter wheeling my suitcases down a ramp.

“Here you are, sir.”

“Thank you.”

I tip him a quarter, he glances at my ticket and to the call of “number eighty-seven!” he flings open the door of a taxi that has drawn to a halt alongside. As I throw away my cigarette it occurs to me that there might exist a hotel called “Peter Stuyvesant” — the man who founded New York and posthumously lent his name to my brand of cigarettes.

“Could be,” the driver reckons when I ask him, and he begins to leaf through a directory. “Say now —there sure is a place like that — on West 86th Street, off Central Park. Is that where you want to go?”

“That’s right!”

And so it happens that by four o’clock of that cold, bright brilliant February afternoon I am traveling through skyscraper canyons toward western Manhattan — relieved to have settled on some destination which the driver is now approaching at breakneck speed. He is a burly man in his fifties, Sydney Enders by name, as I can ascertain by the license plaque fixed to the dashboard. Like most men of his trade he turns out to be a loquacious companion and despite the need for constant vigilance against the fierce traffic, he remains uncommonly willing to answer what questions I have.

“Didja read about that Warren Report they’re making?” he asks, pushing back his visor cap so that I now can make out his rugged face in the rear mirror. “It sure was tough when that crackpot shot the president. Or maybe this Oswald wasn’t a crackpot, just a man with an idea he had to carry through. Still it was tough. As for that Ruby character: I would have guessed he hadn’t a chance what with a hundred million witnesses watching him pull a gun on Oswald. Balls! The police didn’t hold the man for Ruby to shoot, they held him for the TV cameras. The police didn’t even know Ruby was there. He was in and out of that police station so often, he’d become part of the furniture. Didja ever see one of them fancy JFK License Plates? That quote on them sounded all right until you examined it. What I want to know is, when all is said and done: What can the country do for me\ I want to work and to eat, that’s what I say. Everybody should. And never mind the rest... Say Buddy, what the hell are you coming to New York for at this time of year? It’s cold in this burg. You want to head for Florida. That’s the place — I’m off there myself come March: Forty dollars down and the rest on the installment plan. You can get everything on the installment in this country, even a trip to Florida. Yes, I’m taking the wife, though I don’t know why: There’re plenty of women in Miami. But hell, I’m not as young as I was. Might as well take the wife. Youth, brother, that’s what counts in this world. Youth first and next comes money!”

He brings the taxi to a stop in front of the hotel, a multistoried building facing a park on the corner of two wide streets which are both lined with apartment houses and more hotels — quite an impressive place by my standards, though not by his, apparently.

“Never heard of the dump until you mentioned it,” he says derogatively. “How did you come to think of that one?”

I show him my cigarette pack. He laughs.

“I guess it’s as good as the next to stretch your bones in,” he admits, collecting the fare. “Well, good luck, Buddy.”

He slams into gear and, before the lights have turned green, he accelerates round the corner south toward those jutting towers which— more massive now and more substantial than they appeared from Queens — are the extremities of skyscrapers in midtown Manhattan, striving upward as ever through the twilight of a setting sun.

The marathon runner has broken the tape across the finishing line — he has raced with all his might (from Berlin to London, from London across the Atlantic to yet another shore) and now his legs are threatening to fail him, his body is drained of all resilience, and yet it seems as though the perceptiveness of his senses has not been impaired by the effort. He hears the roar of the crowd (it is the five o’clock rush) and the roar of the traffic along Central Park; he sees a million torches flaring up in the distance (they are the city lights reflected from the facades, and aglow above the roof tops of tall apartment buildings in the southern skyline) and from afar he perceives the ominous rumble of thunder (it is the subterraneous sound of trains deep in the subway under the hotel).

Although my room is situated high over the ground on the seventh floor, the mighty metropolis of New York is felt in every crevice; it is ever present, electrifying the very air and when its impact subsides, after I have stretched out on the bed and almost fallen asleep, it reasserts itself with a piercing wail. I sit up, rush to the window, lift it and, leaning out, I see the blue light blinking on the roof of the police car shooting through the traffic amid the incessant sound of a siren. I draw the window down again. The sound of the siren fades away. But it has charged me with a restlessness that, soon afterwards, will drive me from my room down into the streets again. In search of what? Of food, yes, for I am hungry, but also in search of the solution to a problem that has worried me from the moment I moved into this hotel.

What is the meaning of the sign in the window:

These PREMISES temporarily CLOSED

Why does a policeman sit on guard in the lobby? How is it that the reception clerk was so eager to rent me this well-appointed, airy, well-lit and well- heated room for a fraction of the normal price? The clerk, a Polish Jew who spoke a mixture of poor English and German, volunteered nothing. Neither did the Negro lift man or the girl at the telephone switchboard. And the policeman merely inspected me glumly and then stared into space.

And then, an hour later, I encounter that same policeman, a young well-built fellow with a ruddy face, in a nearby cafeteria. The Negro cook who had been resting on a chair in front of the counter jumps up when I enter and, as though he owes me this explanation, he mumbles that the kitchen floor is too wet to stand on all the time. “Yes, sir.” He hurries away to prepare my order. I take the laden tray and sit down at the policeman’s table.

“Good evening.”

“Hello—”

It doesn’t take long before we are talking and soon I gain his confidence by being able to hold my own on the subject of athletics. Athletics are the policeman’s hobby — there isn’t a champion whose record he can’t rattle off by heart: Russians, Australians, Americans ....

“Listen,” I ask eventually, changing the subject and coming straight to the point, “what’s the meaning of that sign in the lobby window of the ‘Peter Stuyvesant?’ ”

“Just what it says,” he tells me. He looks at me. What sort of greenhorn am I? “They’re raided premises,” he explains.

“Why?”

“Damn it. We picked up five call-girls in there the other night, that’s why!”

“And now they have a round-the-clock police guard in there?”

“Sure,” he says. “Till Sunday.”

“That’ll be bad for business.”

“What do I care about their business?” he demands, his tone getting sharper. “All I know, it’s damn bad for me!”

And he launches off on a tirade about the futility of guarding the place, the boredom of it: A man can’t even read a paper while he is sitting there, no one to talk to all night, just twiddling one’s thumbs while the time drags. And all that because of five “damn prostitutes” — a small enough percentage when one considers that there are 128 rooms in the hotel.